Abstract

Introduction:

Perceived stress is linked to poor sexual and reproductive health, but its relationship with sexually transmitted infections (STI) is less clear. The elevated burden of stress and STI among Black women suggests a need to examine racial differences in the associations on additive and multiplicative scales.

Methods:

Using data from Black and White female participants from Wave IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (n=4,744), we examined the association of high stress (scores ≥6 on the Perceived Stress Scale-4) with self-reported past year chlamydia diagnosis; combined curable STI; and lifetime pelvic inflammatory disease using modified Poisson regression with robust variance to estimate prevalence ratios (PRs) and prevalence differences (PDs). Models included a race-stress product-interaction term and adjusted for sociodemographic variables, prior trauma and stressors, and mental health factors.

Results:

In unadjusted analyses, stress was associated with STI among Black and White women. Adjusted associations were attenuated among White women; among Black women, stress remained associated with chlamydia (adjusted PR (APR)=2.22, 95% CI 1.30 – 3.79) and curable STI (APR=1.59, 95% CI 1.05 – 2.40), corresponding to approximately 5 excess cases of each. Among White women, poverty and personality traits were the strongest confounders; among Black women, poverty, trauma, and neurotic personality traits were the strongest confounders for chlamydia, although no factors appeared to confound the association with curable STI.

Conclusions:

Stress is independently linked to STI, particularly among Black women. Additional research with longitudinal data is needed to understand the role of stress on STI and address a significant health disparity.

SUMMARY

In a nationally-representative US sample, we found that perceived stress was associated with past year chlamydia and curable STI, and this relationship was significantly stronger among Black women compared to White women.

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STI) remain a significant public health issue in the United States (US). Rates of curable STI such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae continue to rise each year.1 STI can be especially damaging for women’s health, as these infections are frequently asymptomatic, yet can cause serious consequences including pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) if left undetected and untreated.2 Black women experience among the highest infection rates, a disparity not explained by differences in risk behavior but attributed to untreated reservoirs of infection in sexual networks.1,3 The drastic and sustained increases in STI rates and considerable health disparity underscores the urgent need to identify targets of intervention to prevent infections and their sequelae.

A potentially important but under-researched factor that may influence risk of STI is stress. Stress is defined as an individual’s perception that environmental demands strain or exceed their capacity to respond and is typically operationalized either as the occurrence of an event thought to be taxing of one’s ability to cope (i.e., stressors) or as one’s perceptions of stress due to the event or in general (i.e., perceived stress).4 Perceived stress is hypothesized to increase one’s susceptibility to and pathogenesis of diseases through its impacts on biological and behavioral responses, and has been linked to a wide range of health outcomes such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, and asthma, as well as mental disorders such as depression.4 Perceived stress is associated with adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes, including a twofold increase in the risk of preterm birth5 and bacterial vaginosis (BV).6–9 Stressors such as childhood trauma and intimate partner violence are linked to STI and PID.10–13 However, perceptions of stress have been relatively unexamined despite evidence these perceptions have effects independent of the events14 and may be a more salient intervention target. To date, only three published studies have examined the relationship between perceived stress and STI, and demonstrated a positive association. However, there are remaining gaps in the literature. First, extant studies have been conducted within relatively non-generalizable, geographically limited, and non-population based samples.15–17 Further, these studies typically control for a small set of potential confounding factors. Finally, no prior studies have examined the association between perceived stress and downstream sequelae of STI such as PID. PID may be particularly vulnerable to the influence of stress, given effects of stress on behavioral factors such as care seeking and biological factors such as inflammation.18

Moreover, extant research on stress and STI has been conducted within samples of predominantly Black women, and hence none has been able to assess racial differences in associations. In studies of other sexual and reproductive health outcomes like BV, Black women report more stressful life events and higher levels of perceived stress than White women, though only a few studies have examined whether the risk associated with these factors varies by race.7,9 The racial disparity in STI highlights the need to examine factors that may impact STI and PID within these groups in order to inform targeted prevention interventions. There is also a need to assess potential differences on both relative and absolute scales given differing baseline rates of both stress and STI between Black and White women.

To address these gaps, we examined associations between perceived stress and STI and PID in a large, nationally-representative, population-based sample of US White and Black women aged 24–34 years. We estimated relative and absolute measures of the association, controlling for a range of confounding factors such as sociodemographic factors, prior trauma, and mental health factors, and we assessed whether the prevalence ratios and prevalence differences varied between White and Black women. We hypothesized that perceived stress would be associated with higher prevalence of STI and PID, and that the associations would be stronger among Black women compared to White women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Sample

We conducted a secondary analysis of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Add Health is a nationally-representative sample of US adolescents in grades 7–12 during 1994–1995 (11–21 years of age) who were followed into adulthood through additional waves of data collection. Details of Add Health’s study design have been described elsewhere.19 Briefly, during Wave I, a random sample of 20,745 students drawn from a stratified random sample of US high school and feeder middle schools participated in an in-home interview using computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) and, for more sensitive questions, audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI). Of the Wave I cohort, a total of 15,197 participants during young adulthood (Wave III; 2001–2002; 18–28 years) and 15,701 participants during adulthood (Wave IV; 2007–2008; 24–34 years) participated in CAPI/ACASI in-home interviews (response rates of 77.4% and 80.3% respectively). This analysis of de-identified data is considered to be non-human subjects research by the Institutional Review Board of New York University School of Medicine.

We followed Add Health’s analytic guidelines for the present secondary data analysis study by creating a subpopulation of the 5,968 White and Black women at Add Health Wave IV who had data for all study variables and valid Wave IV survey sample weights.20 This resulted in an analytic sample of 4,774 women (White women N=3,383; Black women N=1,391).

Measures

Sexually Transmitted Infection and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

In the Wave IV in-home interview, participants reported past year diagnoses by a doctor or nurse of the following: chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, trichomoniasis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Chlamydia was the most commonly reported diagnosis, which allowed for analyses examining that STI individually. However, the prevalence was relatively low for all other diagnoses and we therefore created a combined indicator of curable STI (i.e., chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, trichomoniasis) based on the World Health Organization categorizations.21 Past year diagnosis of PID was very rare and hence we were only able to examine lifetime PID diagnosis.

Perceived Stress

Perceived stress was measured in the Wave IV in-home interview using the four-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4).22 The PSS-4 evaluates the degree to which individuals believe that their life has been unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded in the past 30 days. Though the PSS-4 measures a recent time period, the scale has been shown to be relatively stable over time and is believed to capture one’s overall liability to be stressed and to be indicative of chronic stress.17,22 Participants rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from “never” to “very often” the frequency with which they felt unable to control their lives, confident in their ability to handle problems, that things were going their way, and unable to overcome difficulties. Positive items were reverse-coded and all were summed to create a score (range 0–16), with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress. Because perceived stress was not linear in relation to the outcomes, we created a dichotomous indicator of high stress that was split at the 75th percentile (scores ≥6) in the total sample. This cut-point was chosen considering previous studies, where the relationship between perceived stress and sexual and reproductive health outcomes has been analyzed based on dividing the scale into quartiles or using a cut-point of 6 on the PSS-4.6,8,17

Covariates

Based on the extant literature regarding stress and sexual and reproductive health, we identified a range of relevant sociodemographic covariates, stressful experiences, and mental health indicators measured at various points throughout Add Health’s longitudinal data collection. Sociodemographic covariates included age at Wave IV, dichotomized at the sample median of 28 years given that it did not show a linear association with the log odds of perceived stress in the propensity score model (described below); education at Wave IV, categorized as less than high school, high school graduate, some college/vocational training, and college graduate or greater; and poverty at young adulthood and adulthood, defined as reporting not having enough money to pay housing and/or utility bills in the past 12 months.

We measured stressful experiences using data captured at Waves I, III and IV. History of childhood traumatic experiences before the age of 18 included self-report of physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse, and neglect at Waves III (defined as occurring before 6th grade) and/or IV (defined as occurring before one’s 18th birthday); incarceration of a parent before the participant was 18 years of age, measured at Wave IV; or being threatened with, witnessing, and/or experiencing physical violence in the past year measured at Wave I. History of criminal justice involvement was defined as report of having been arrested at Waves III and/or IV, incarcerated at Wave IV, or on probation/parole at Wave III. History of intimate partner violence was defined as reporting a partner ever shoved, hit, and/or forced sex at Wave IV; and experience of everyday discrimination at Wave IV was defined as reporting they “sometimes/often” felt treated with less respect or courtesy than others in their day-to-day life versus “never/rarely.”

Mental health indicators were also captured across waves and included depression during adolescence (i.e., Wave I) and young adulthood (i.e., Wave III), measured using a nine-item version of the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale on which positive items were reverse-coded, responses were summed, and scores dichotomized at ≥10.23 We included a continuous indicator of neurotic personality traits during adolescence (i.e., Wave I),24 on which participants rated on a Likert-type scale the degree to which they agreed with items such as having a low opinion about oneself and worrying about things.

Analyses

We used survey commands in Stata 15.1 to account for the complex survey design and obtain representative estimates. We estimated the frequency and weighted prevalence of high stress by sociodemographic characteristics, stressful experiences, and mental health covariates. Unadjusted modified Poisson regression models were used to estimate the prevalence ratios (PRs), prevalence differences (PDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between each covariate and high stress,25 and to estimate the PRs and PDs with 95% CIs for associations between stress and the STI and PID outcomes. Because we were interested in potential racial differences, we examined whether associations differed between White and Black women by including a product-interaction term between race and stress, and present all estimates stratified by race. We interpreted p-values ≤0.15 as suggestive of race differences given tests of interaction are low-powered.26

To account for potential confounding by the sociodemographic characteristics, stressful experiences, and mental health factors, we used inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) methods, regressing perceived stress on the covariates to estimate a propensity score (PS) and then calculating the IPTW for exposed (i.e., high stress) and unexposed (i.e., low stress) as 1/PS and 1/(1-PS) for each group respectively.27

We also explored potential differences in confounding factors across the racial groups.28 Specifically, for each covariate, we estimated a propensity score model that excluded that variable, calculated the IPTW as described above, and estimated the associations between stress and the outcomes obtained from the model weighted by the IPTW with the covariate removed and then compared that to the estimates obtained from the model weighted by the IPTW that included all covariates, calculating the change-in-estimate as: [(PROriginal IPTW – PRCovariate Removed IPTW)/ PROriginal IPTW].

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Associations with Stress

Among White and Black women, in bivariate analyses, sociodemographic characteristics, occurrence of stressful experiences, and mental health measures were associated with high perceived stress. History of childhood trauma, criminal justice involvement, intimate partner violence, and depression during young adulthood each had positive associations with stress that were similar among White and Black women (Table 1). Among White women, those aged 29–35 years had lower prevalence of stress compared to those aged 24–28 (PR=0.88, 95% CI 0.78 – 0.99), while age was not associated with stress among Black women; this difference between the racial groups was not significant on the multiplicative or additive scale. Relative to those with less than a high school education, the prevalence of stress decreased among those with increasing education in Black and White women, and the association was significantly stronger among White women. Similarly, poverty, discrimination, and depression during adolescence were associated with stress among White and Black women, but the relationships were stronger among White women.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Associations with High Perceived Stress (PSS Score ≥6) among Adult Women (Aged 24–34 Years)

| White Women (N=3,383) | Black Women (N=1,391) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) with Elevated Perceived Stress | PR (95% CI) | PD (95% CI) | N (%) with Elevated Perceived Stress | PR (95% CI) | PD (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 24–28 Years | 612 (41.3) | Ref | 287 (48.9) | Ref | ||

| 29–35 Years | 677 (36.3) | 0.88 (0.78, 0.99) | −4.97 (−9.71, −0.23) | 351 (48.2) | 0.98 (0.85, 1.13) | −0.78 (−7.67, 6.10) |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than High School | 105 (63.4) | Ref | 57 (67.2) | Ref | ||

| High School Graduate | 200 (43.7) | 0.70 (0.60, 0.83)a | −19.65 (−31.09, −8.21) | 84 (53.0) | 0.75 (0.63, 0.88)a | −14.22 (−30.19, 1.74) |

| Some College | 526 (45.1) | 0.70 (0.62, 0.80)a | −18.24 (−27.14, −9.33) | 287 (51.0) | 0.75 (0.66, 0.85)a | −16.22 (−29.98, −2.46) |

| College Graduate or More | 458 (28.8) | 0.46 (0.40, 0.53)a | −34.52 (−43.57, −25.47) | 210 (38.4) | 0.49 (0.43, 0.55)a | −28.79 (−40.84, −16.74) |

| Poverty during Young Adulthood | ||||||

| No | 1017 (35.9) | Ref | 483 (47.8) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 272 (54.4) | 1.51 (1.32, 1.73)a | 18.46 (11.49, 25.43)b | 155 (50.8) | 1.06 (0.92, 1.23)a | 3.09 (−4.28, 10.46)b |

| Poverty during Adulthood | ||||||

| No | 888 (33.1) | Ref | 409 (42.7) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 401 (63.4) | 1.91 (1.75, 2.09)a | 30.29 (25.68, 34.90)b | 229 (62.0) | 1.45 (1.20, 1.76)a | 19.29 (9.02, 29.57)b |

| History of Childhood Trauma | ||||||

| No | 644 (31.3) | Ref | 243 (39.2) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 645 (50.1) | 1.60 (1.44, 1.77) | 18.78 (14.56, 22.99) | 395 (55.9) | 1.42 (1.23, 1.65) | 16.67 (10.32, 23.02) |

| History of Criminal Justice Involvement | ||||||

| No | 945 (36.6) | Ref | 460 (46.2) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 344 (45.9) | 1.25 (1.12, 1.40) | 9.32 (4.53, 14.11) | 178 (55.0) | 1.19 (1.00, 1.42) | 8.84 (−0.27, 17.95) |

| History of Intimate Partner Violence | ||||||

| No | 969 (35.6) | Ref | 420 (42.7) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 320 (53.7) | 1.51 (1.34, 1.70) | 18.16 (12.50, 23.83) | 218 (63.8) | 1.50 (1.30 1.72) | 21.13 (13.58, 28.68) |

| Everyday Discrimination | ||||||

| Never/Rarely | 834 (32.3) | Ref | 389 (43.1) | Ref | ||

| Sometimes/Often | 455 (60.0) | 1.86 (1.69, 2.03)a | 27.66 (23.13, 32.20)b | 249 (60.9) | 1.41 (1.19, 1.68)a | 17.80 (8.84, 26.75)b |

| Depression during Adolescence | ||||||

| No | 924 (35.3) | Ref | 432 (44.9) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 365 (53.0) | 1.50 (1.34, 1.69)a | 17.75 (12.13, 22.37) | 206 (58.8) | 1.31 (1.14, 1.50)a | 13.86 (6.55, 21.17) |

| Depression during Young Adulthood | ||||||

| No | 1030 (35.3) | Ref | 464 (43.6) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 259 (63.5) | 1.80 (1.61, 2.01) | 28.18 (21.73, 34.64) | 174 (70.0) | 1.61 (1.38, 1.87) | 26.44 (17.73, 35.14) |

| Elevated (≥12) Neurotic Personality Traits Score | ||||||

| No | 413 (30.3) | Ref | 316 (44.9) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 876 (44.7) | 1.47 (1.32, 1.65)a | 14.34 (10.32, 18.37)b | 322 (52.6) | 1.17 (1.04, 1.33)a | 7.69 (1.64, 13.73)b |

Abbreviations: PR = Prevalence Ratio; PD = Prevalence Difference; CI = Confidence Interval

Significant (p value ≤0.15) differences in the association between White and Black women on the multiplicative scale

Significant (p value ≤0.15) differences in the association between White and Black women on the additive scale

Associations between Stress, STI, and PID

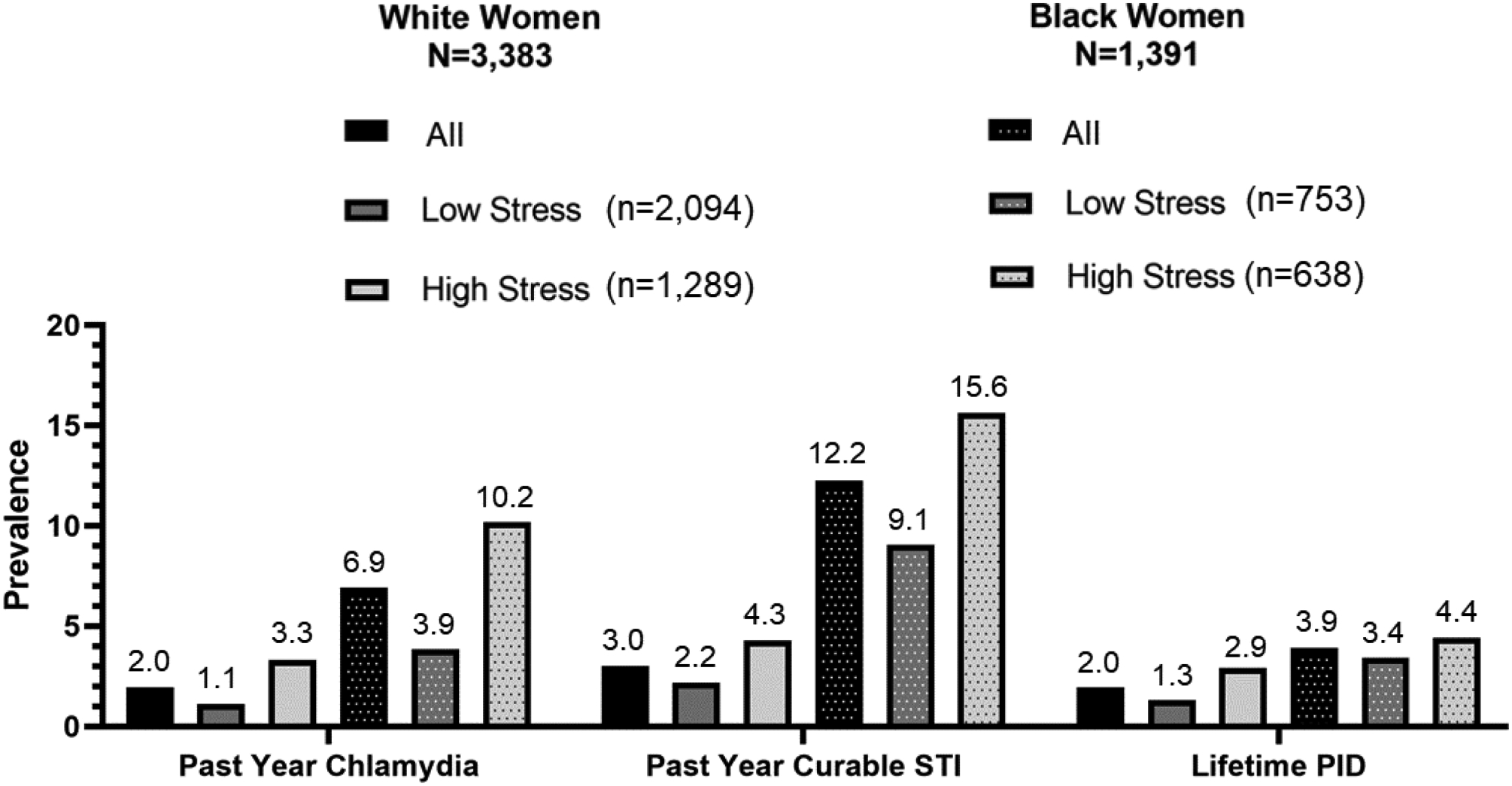

The prevalences of self-reported past year STI and lifetime PID diagnoses were significantly higher among Black women compared to White women (Figure 1). Approximately 2% (N=59) of White women and 7% (N=92) of Black women reported receiving a diagnosis of chlamydia in the past year; 3% (N=92) of White women and 12% (N=161) of Black women reported a curable STI diagnosis; and 2% (N=61) of White women and 4% (N=52) of Black women reported ever receiving a PID diagnosis. Among White and Black women, the prevalence of self-reported STI was higher among those reporting high stress. For example, the prevalence of past year chlamydia diagnosis was approximately 1% among White women with low stress and 3% among those with high stress; among Black women, the prevalence was approximately 4% and 10% respectively.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Past Year Chlamydia, Curable STI, and Lifetime PID among White and Black Women

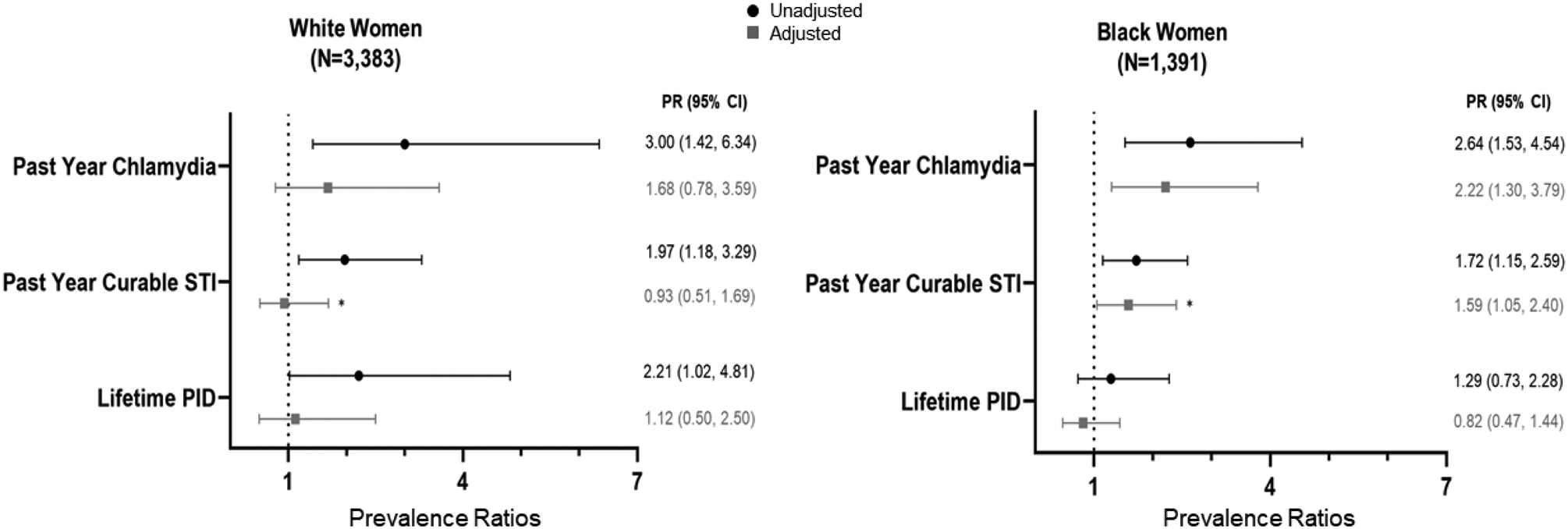

On the multiplicative scale, the relationship between stress and past year chlamydia did not differ by race. White women with high stress had three times the prevalence of past year chlamydia compared to White women with low stress (PR=3.00, 95% CI 1.42 – 6.34; Figure 2), though the association was reduced in the final adjusted model [adjusted PR (APR)=1.68, 95% CI 0.78 – 3.59). Among Black women, there was over a two-fold increase in the prevalence of past year chlamydia for those with high stress versus low stress (PR=2.64, 95% CI 1.30 – 3.79), and this association was relatively unchanged in the final adjusted model (APR=2.22, 95% CI 1.30 – 3.79). The relationship between stress and past year curable STI did appear to differ by race. Specifically, among White women, curable STI prevalence was approximately two times higher for those reporting high stress than those with low stress (PR=1.97, 95% CI 1.18 – 3.29), yet the association became null in the final adjusted model (APR=0.93, 95% CI 0.51 – 1.69). Among Black women, high stress was associated with approximately 1.6 times the prevalence of curable STI in the final adjusted model, which differed from the null association among White women (p-value for interaction=0.14). Among White women, high stress was associated with over twice the prevalence of PID (PR=2.21, 95% CI 1.02 – 4.81), but the association was greatly reduced in the final adjusted model (APR=1.12, 95% CI 0.50 – 2.50). Stress did not appear associated with PID among Black women, and associations did not differ by race.

Figure 2.

Prevalence Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Associations between Elevated Stress and Past Year Chlamydia, Curable STI, and Lifetime PID among White and Black Women

Abbreviations: PR= Prevalence Ratio; Cl = Confidence Interval; STI = Sexually Transmitted Infection; PID = Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Adjusted (in grey) using IPTW, weighting on age, education, poverty during young adulthood, poverty during adulthood, history of childhood trauma, history of criminal justice involvement, history of intimate partner violence, discrimination, depression during adolescence, depression during young adulthood, and neurotic personality trait score during adolescence

*Indicates difference in the association between White and Black women on the multiplicative scale; past year curable STI p-value=0.14

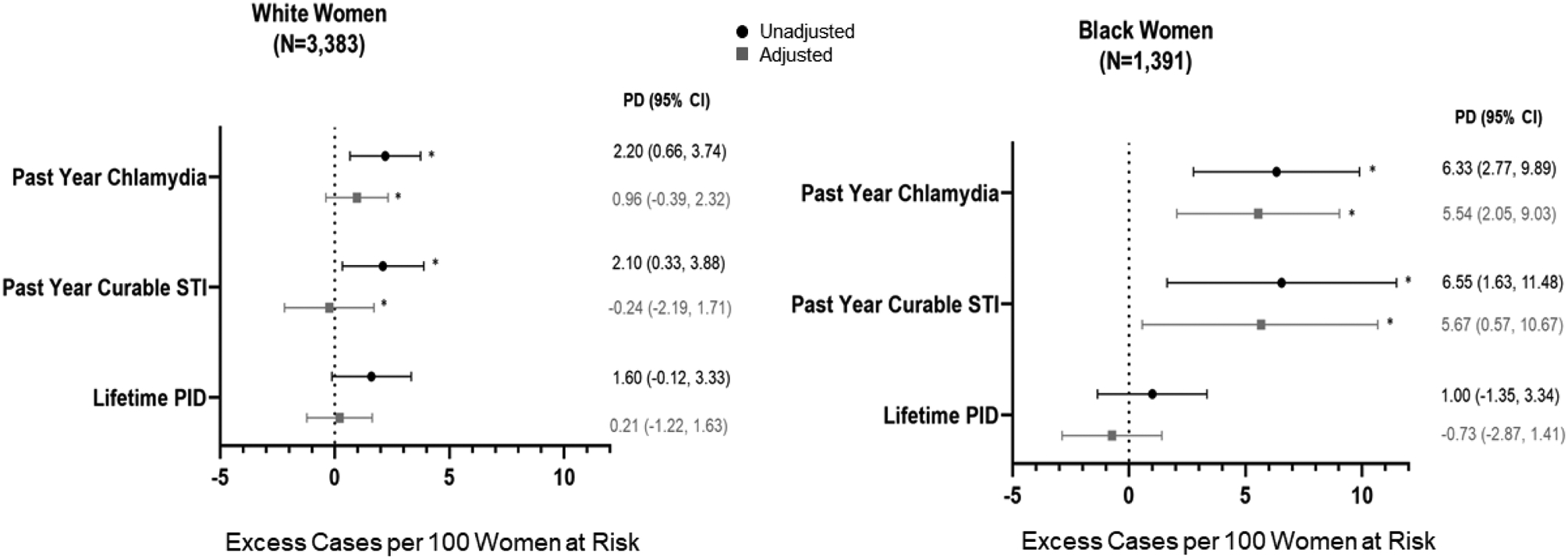

On the additive scale, the excess cases of past year chlamydia and curable STI associated with high stress were elevated among Black women compared to White women (Figure 3). Among White women, after adjustment there was no association between stress and past year chlamydia or curable STI on the additive scale. Among Black women, stress was associated with more than 5 excess prevalent cases of past year chlamydia [adjusted PD (APD)=5.54, 95% CI 2.05 – 9.03)] and past year curable STI (APD=5.67, 95% CI 0.57 – 10.67) per 100 Black women at risk. Also similar to the results from the multiplicative scale, the higher number of excess prevalent cases of PID associated with stress among White women was reduced to null after adjustment and was not associated among Black women; these associations did not differ by race.

Figure 3.

Prevalence Differences and 95% Confidence Intervals for Associations between Elevated Stress and Past Year Chlamydia, Curable STI, and Lifetime PID among White and Black Women

Abbreviations: PD = Prevalence Difference; Cl = Confidence Interval; STI = Sexually Transmitted Infection; PID = Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Adjusted (in grey) using IPTW, weighting on age, education, poverty during young adulthood, poverty during adulthood, history of childhood trauma, history of criminal justice involvement, history of intimate partner violence, discrimination, depression during adolescence, depression during young adulthood, and neurotic personality trait score during adolescence

*Indicates difference in the association between White and Black women on the multiplicative scale; past year chlamydia p-value unadjusted=0.04, adjusted=0.02; past year curable STI p-value unadjusted=0.08, adjusted=0.03

Assessment of Factors Confounding the Stress-STI Associations

We examined the change in estimate by each covariate when an association between stress and an outcome was observed. Specifically, we compared each estimate obtained when omitting individual covariates to the final adjusted estimates for past year chlamydia (White women APR=1.68, 95% CI 0.78 – 3.59; Black women APR=2.22, 95% CI 1.30 – 3.79), past year chlamydia (White women APR=0.93, 95% CI 0.51 – 1.69; Black women APR=1.59, 95% CI 1.05 – 2.40), and lifetime PID among White women (APR=1.12, 95% CI 0.50 – 2.50). Among White women all the covariates with the exception of age and education exerted a sizable influence on the observed PRs for all the outcomes, consistent with their hypothesized role as confounders in our model (Table 2). The strongest influences were poverty during young adulthood and neurotic personality traits. For example, when poverty was omitted from the IPTW, the estimate for the association with past year curable STI changed 100% (original APR=0.93; poverty-omitted PR=1.86). Among Black women, poverty during young adulthood, childhood trauma, IPV, depression during young adulthood, and neurotic personality traits appeared to act as confounders of the association with past year chlamydia but not for past year curable STI, and the largest change in estimate was approximately 16%.

Table 2.

Assessment of Factors Confounding the Associations between High Perceived Stress and Sexually Transmitted Infection and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease among Adult Women (Aged 24–34 Years)

| % Change in PR without Age | % Change in PR without Education | % Change in PR without Poverty in Young Adulthood | % Change in PR without Poverty in Adulthood | % Change in PR without Childhood Trauma | % Change in PR without History of CJI | % Change in PR without IPV | % Change in PR without Discrimination | % Change in PR without Depression in Adolescence | % Change in PR without Depression in Young Adulthood | % Change in PR without Neurotic Personality Traits | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past Year Chlamydiaa | |||||||||||

| White | −6.6 | −1.2 | −70.8 | −33.9 | −30.4 | −36.1 | −32.1 | −20.8 | −38.1 | −30.4 | −75.0 |

| Black | −0.4 | 0.9 | −15.8 | 0.4 | −16.7 | −0.9 | −15.3 | −8.1 | −3.6 | −12.2 | −16.7 |

| Past Year Curable STIb | |||||||||||

| White | −3.2 | −2.2 | −100.0 | −32.3 | −53.8 | −36.6 | −52.7 | −43.6 | −36.6 | −50.5 | −107.5 |

| Black | −0.6 | −1.9 | −4.4 | 1.3 | −6.3 | −0.6 | −3.1 | −4.4 | −1.3 | −3.1 | −6.3 |

| Lifetime PIDc | |||||||||||

| White | −9.8 | −1.8 | −83.9 | −19.6 | −66.1 | −22.3 | −66.1 | −32.1 | −25.0 | −59.8 | −96.4 |

| Black | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Abbreviations: PR = Prevalence Ratio; CJI = Criminal Justice Involvement; IPV = Intimate Partner Violence; STI = Sexually Transmitted Infection; PID = Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Past Year Chlamydia Original Adjusted Estimates: White women APR=1.68; Black women APR=2.22

Past Year Curable STI Original Adjusted Estimates: White women APR=0.93; Black women APR=1.59

Lifetime PID Original Adjusted Estimate: White women APR=1.12

DISCUSSION

In this nationally-representative sample, women reporting high levels of perceived stress reported greater prevalence of past year diagnoses of curable STI, including chlamydia, compared to those with low perceived stress. When examining racial differences in the relationships between stress and STI, we found that the association was essentially the same on the multiplicative scale but differed on the additive scale. Specifically, among both White and Black women, stress was associated with having more than twice the prevalence of STI prior to adjustment. When adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, stressful experiences, and mental health factors, this association remained strong among Black women while among White women the association was attenuated. However, considering the baseline STI prevalence was already quite elevated among Black women, we observed that stress was linked to a substantially higher STI burden compared to White women on the additive scale in unadjusted and adjusted models. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the causal role of stress on STI risk and the potential for reducing stress to reduce STI. This line of research would serve to address a significant public health disparity considering that almost two million cases of chlamydia were reported in the US in 2017 and Black women experience a disproportionately high burden of infection.1

Our results identifying stress as an independent correlate of STI support findings from a limited body of prior studies. In a sample of young primarily Black women in Pennsylvania, those reporting high perceived stress had approximately twice the odds of self-reported lifetime and current biologically-confirmed chlamydia and/or gonorrhea.15 The only known longitudinal analysis in a cohort of Black women in Alabama demonstrated that each unit increase in perceived stress was associated with approximately 2% increased risk of incident chlamydia, gonorrhea, or trichomoniasis, corresponding to about twice the risk for those in the highest quartile of stress versus the lowest.17 Our current cross-sectional analysis yielded similar results, suggesting that our findings may not be due solely to reverse causality. However, we cannot establish causality and a reverse causal association is plausible. Perceived stress is hypothesized to be stable and indicative of chronic stress, thus potentially preceding the outcomes in this study, although this may be less likely for the outcome of lifetime PID, considering that perceived stress is unlikely to be stable across the entire early adulthood lifecourse. Our hypothesis that our measure of perceived stress is indicative of chronic stress and hence precedes STI in our study is further supported by the sole longitudinal study on this topic that demonstrated that perceived stress was relatively constant and predictive of later STI.17

Our study extends previous findings linking stress and STI to a large, nationally-representative sample, allowing for both improved generalizability to US White and Black US women and is the first published examination of racial differences. Stress may influence risk of STI through both biological and behavioral factors. The aforementioned study among women in Alabama found that behavioral factors such as multiple sexual partnerships and biological factors such as bacterial vaginosis appeared to explain some of the observed relationship between stress and STI.17 Further research in large, representative, and longitudinal samples is needed to explore the mechanisms through which stress may influence STI risk, and whether that differs for White and Black women.

Accounting for factors like poverty and mental health greatly attenuated associations among White women, while among Black women there was relatively little evidence that these factors influenced the observed associations. This may reflect differences between White and Black women in the prevalence of other common causes of stress and STI, or differences in the way stressors are experienced and perceived between these groups.9 Individual-level stressors may not account for overall perceptions of being overwhelmed and unable to control one’s life among Black women, which may instead be driven by other social and structural stressors such as racism and segregation. These community-level stressors coupled with one’s perceived control over them may influence perceived stress and subsequent effects on health among Black women.29 Future research should continue to examine individual, community, and structural factors that influence stress, as well as the buffering effects of control and social support, to inform development of interventions that can both reduce upstream drivers of stress and increase coping in the face of stress.

In addition to the cross-sectional data that limits temporal assessment, this study has other limitations. Measures are self-reported and subject to recall and social desirability bias given their sensitive nature. However, the prevalence of STI we estimated closely correspond to patterns from other national studies; in our sample of women aged 24–34 years the prevalence of self-reported past year chlamydia diagnosis was 6% and 2% among Black and White women respectively, which was consistent with the prevalence estimates of 8% and 2% among Black and White women respectively in the 2013–16 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey among women aged 14–24 years.1 We also are not able to assess the frequency with which participants received STI testing, which could differ by stress level as well as by race. There is also the potential for residual unmeasured confounding. For example, we hypothesized sexual behavior may mediate the relationship between stress and STI, as has been demonstrated in prior studies,17 but it could potentially confound associations in this analysis. However, the minimum amount of unmeasured confounding on the ratio scale (i.e., the E-value)30 needed to reduce the adjusted associations we observed among Black women for past year chlamydia and curable STI to null associations is large, at 3.9 and 2.6 respectively. Our analytic sample consisted of White and Black women retained at Wave IV with non-missing data for prior waves, which may limit generalizability and could bias estimates, although Add Health suggests that bias due to differential attrition is small when estimates account for sampling weights. Moreover, we focused our analyses among women but the relationship among stress and STI among men is under-researched and warrants attention. Finally, the data used in this analysis were collected in Add Health Wave IV during 2008 and it possible that relationships among stress and STI may be different in the present day. However, our findings are aligned with those estimated in a study where data were collected in 1999,17 approximately 10 years prior to Wave IV, suggesting that these effects may be stable over time; additional research using more current data are needed.

In conclusion, this study is among the first to examine differences in the relationship of perceived stress and past year curable STI and lifetime PID between White and Black women. Our findings that prior poverty, trauma, and mental health factors had large influences on the estimates highlight that addressing upstream stressors may serve to reduce STI for White women and additional attention should be paid to the remaining heightened perceived stress among Black women to prevent disproportionate STI burden. Future studies should use longitudinal studies to rigorously assess the potential causal relationship between stress and STI risk, and examine pathways that may link them to inform primary and secondary prevention intervention programming as well as protective factors that may mitigate the negative effects.

Acknowledgement and Funding Sources:

We sincerely thank Drs. James Jaccard and Anne Zeleniuch-Jacquotte for their comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. JD Scheidell was supported by T32 DA7233. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01HD31921 for this analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) - CDC Fact Sheet. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/std/pid/stdfact-pid.htm (accessed February 2018).

- 3.Harawa NT, Greenland S, Cochran SD, Cunningham WE, Visscher B. Do differences in relationship and partner attributes explain disparities in sexually transmitted disease among young white and black women? J Adolesc Health 2003; 32(3): 187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA 2007; 298(14): 1685–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro GD, Fraser WD, Frasch MG, Seguin JR. Psychosocial stress in pregnancy and preterm birth: associations and mechanisms. J Perinat Med 2013; 41(6): 631–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culhane JF, Rauh V, McCollum KF, Hogan VK, Agnew K, Wadhwa PD. Maternal stress is associated with bacterial vaginosis in human pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 2001; 5(2): 127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul K, Boutain D, Manhart L, Hitti J. Racial disparity in bacterial vaginosis: the role of socioeconomic status, psychosocial stress, and neighborhood characteristics, and possible implications for preterm birth. Soc Sci Med 2008; 67(5): 824–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harville EW, Savitz DA, Dole N, Thorp JM Jr., Herring AH. Psychological and biological markers of stress and bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. BJOG 2007; 114(2): 216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culhane JF, Rauh V, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Hogan V. Exposure to chronic stress and ethnic differences in rates of bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187(5): 1272–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: a retrospective study. Pediatrics 2000; 106(1): E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(10): 1157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.London S, Quinn K, Scheidell JD, Frueh BC, Khan MR. Adverse Experiences in Childhood and Sexually Transmitted Infection Risk From Adolescence Into Adulthood. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44(9): 524–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champion JD, Piper J, Holden A, Korte J, Shain RN. Abused women and risk for pelvic inflammatory disease. West J Nurs Res 2004; 26(2): 176–91; discussion 92–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen S, Tyrrell DA, Smith AP. Negative life events, perceived stress, negative affect, and susceptibility to the common cold. J Pers Soc Psychol 1993; 64(1): 131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzaferro KE, Murray PJ, Ness RB, Bass DC, Tyus N, Cook RL. Depression, stress, and social support as predictors of high-risk sexual behaviors and STIs in young women. J Adolesc Health 2006; 39(4): 601–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz RJ, Fullerton J, Brown CE, Schoolfield J. Relationships of cortisol, perceived stress, genitourinary infections, and fetal fibronectin to gestational age at birth. Biol Res Nurs 2001; 3(1): 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turpin R, Brotman RM, Miller RS, Klebanoff MA, He X, Slopen N. Perceived stress and incident sexually transmitted infections in a prospective cohort. Ann Epidemiol 2019; 32: 20–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geronimus AT. Understanding and eliminating racial inequalities in women’s health in the United States: the role of the weathering conceptual framework. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972) 2001; 56(4): 133–6, 49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 1997; 278(10): 823–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen P, Chantala K. Guidelines for Analyzing Add Health Data. 2014. www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/documentation/guides/wt_guidelines_20161213.pdf (accessed May 2019).

- 21.World Health Organization. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) (accessed May 2019).

- 22.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24(4): 385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc 1991; 20(2): 149–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young JK, Beaujean AA. Measuring personality in wave I of the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Front Psychol 2011; 2: 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159(7): 702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selvin S Statistical Analysis of Epidemiologic Data. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015; 34(28): 3661–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol 1993; 138(11): 923–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker AB, Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Klem L. Age differences in health effects of stressors and perceived control among urban African American women. J Urban Health 2005; 82(1): 122–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med 2017; 167(4): 268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]