Abstract

Axon remodeling through sprouting and pruning contributes to the refinement of developing neural circuits. A prominent example is the pruning of developing sensory axons deprived of neurotrophic support, which is mediated by a caspase-dependent (apoptotic) degeneration process. Distal sensory axons possess a latent apoptotic pathway, but a cell body-derived signal that travels anterogradely down the axon is required for pathway activation. The signaling mechanisms that underlie this anterograde process are poorly understood. Here we show that the tumor suppressor P53 is required for anterograde signaling. Interestingly loss of P53 blocks axonal but not somatic (i.e., cell body) caspase activation. Unexpectedly, P53 does not appear to have an acute transcriptional role in this process and instead appears to act in the cytoplasm to directly activate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in axons. Our data support the operation of a cytoplasmic role for P53 in the anterograde death of developing sensory axons.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

The survival of developing embryonic sensory axons is controlled by the level of target-derived neurotrophins. Simon et al. report that the transcriptional regulator P53 controls the death of these axons non-canonically, acting in the cytoplasm, not the nucleus, to activate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.

Introduction

Developing sensory axons are produced in excess and their survival is determined by competition for limiting quantities of the target-derived neurotrophin Nerve Growth Factor (NGF). Loss of NGF produced by epidermis triggers axon degeneration driven by an intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Schuldiner and Yaron, 2015).

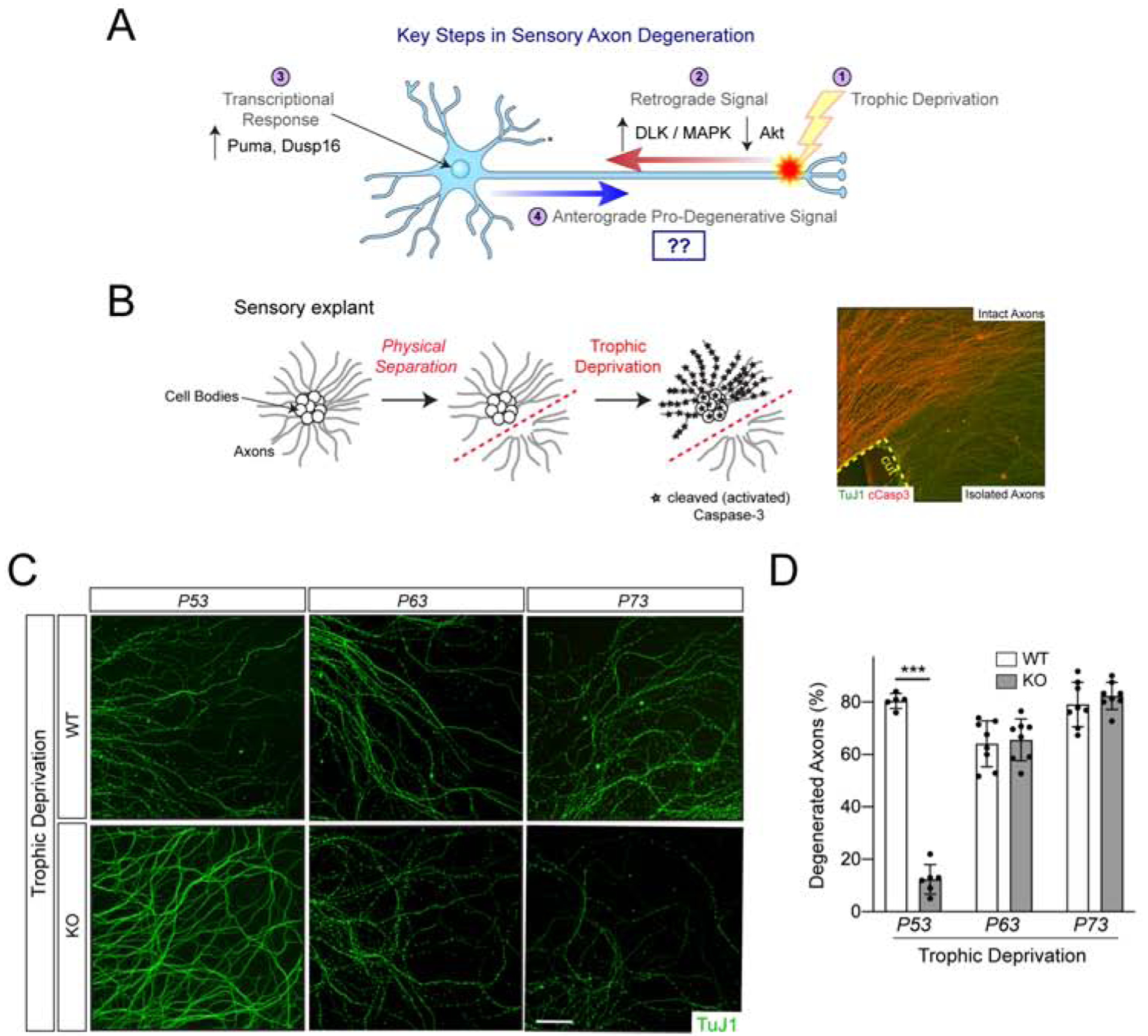

Coupling of trophic deprivation (TD) to activation of the axonal apoptotic pathway had long-been considered to be compartmentalized within the axon, but recent studies have demonstrated a critical role for the cell body in this process. TD of the distal axon initiates a retrograde signal to the cell body, culminating in transcription of the Bbc3 gene, encoding the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein Puma. Loss of Puma, chemical inhibition of transcription, or physically severing sensory axons from their cell bodies all block axonal Caspase-3 activation and inhibit axon death (Figure 1A,B) (Maor-Nof et al., 2016; Simon et al., 2016). Importantly, the components of the apoptotic pathway are present in axons, as demonstrated by the ability of a small molecule Bax activator to stimulate Caspase-3-dependent degeneration of axons disconnected from their cell bodies, implying that an anterograde pro-degenerative activity emanates from the cell body to gate activation of this latent pathway during TD. This activity, though Puma-dependent, appears distinct from Puma, a short half-life protein which we find is restricted to the cell body as assessed by immunoblotting and mass spectrometry (Simon et al., 2016).

Figure 1: P53 is required for sensory axon degeneration.

(A) Sensory axon degeneration is a multi-step process initiated by TD of the axon. (B) Axonal Caspase-3 activation upon TD is blocked by physically separating axons from their cell bodies. Here, injury-induced degeneration is blocked by expression of cytoplasmic NMNAT1 (Simon et al., 2016). (C) 7DIV explants from the specified genotypes were subjected to TD and visualized with an antibody to βIII tubulin (TuJ1). Substantial degeneration is seen by 25hr of TD (shown), n=3 experiments. The Trp53tm1Tyj/J allele is used here. (D). Here, and throughout, values are presented as mean ± SEM; p < 0.001, unpaired t-test. Scale bar 100μm.

We studied the regulation of Puma as an entry point to dissect anterograde signaling. In certain contexts, Puma mRNA expression is regulated by the tumor suppressor P53 in its role as a pro-apoptotic transcription factor (Nakano and Vousden, 2001; Villunger et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2001). This induction was, for example, recently shown to account for the neurotoxic effects of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-associated PR(50) dipeptides in cortical neurons (Maor-Nof et al., 2021). However, a role for P53 in the cytoplasm has also been proposed based on structural and biochemical studies demonstrating that P53 can directly bind and activate Bax (Follis et al., 2018; Follis et al., 2015) or its close family member Bak (Leu et al., 2004), and on experiments in which expression of P53 mutants incapable of binding DNA, or wild type P53 in the absence of a nucleus, are both nevertheless pro-apoptotic (Chipuk et al., 2005; Chipuk et al., 2004; Chipuk et al., 2003; Dumont et al., 2003; Green and Kroemer, 2009; Haupt et al., 1995; Marchenko et al., 2000; Mihara et al., 2003).

In neural development, P53 controls the apoptosis of NGF-dependent sympathetic neurons (Aloyz et al., 1998; Vogel and Parada, 1998) and of neural progenitors in the ventricular zone (Miller et al., 2000), but its role in regulating axon degeneration is unknown. Here we found that sensory axons are protected from degeneration in cultures lacking P53, but that P53 does not appear to function via Puma in this context, as Puma is still robustly expressed and further induced by TD in P53 knockout cultures. Moreover, P53 specifically promotes axonal but not somatic caspase activation upon TD, suggesting a role downstream or in parallel to Puma in promoting anterograde pathway activation. Our evidence further indicates, unexpectedly, that P53 functions not in the nucleus but in the cytoplasm, downstream of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL in activation of the Bax-dependent mitochondrial pro-degenerative pathway. These results define cytoplasmic P53 as a critical regulator of the anterograde pathway of sensory axon degeneration.

Results

Given the relationship between P53 and Puma, we examined TD-induced sensory axon degeneration in P53 knockout explants and observed strong axon protection in these cultures. By contrast, loss of family members P63 and P73, which share the same preferred DNA binding motif as P53, provided no apparent axon protection (Figure 1C,D). Fractionation of sensory neuron cultures into axons and cell bodies revealed that P53 is strongly expressed in cell bodies, as expected, but it is also detectable in axons, albeit to a lesser degree, as assessed by immunoblot (Supplementary Figure 1A). Upon TD, we found that somatic P53 is phosphorylated at an N-terminally located residue associated with activation (Shieh et al., 1997) (Supplementary Figure 1B,C).

To explore how P53 promotes axon degeneration we subjected wild type and P53 knockout cultures to TD, followed by independent harvesting of axons and cell bodies. Consistent with previous results (Simon et al., 2016), Puma is basally expressed in the cell body and its levels rise during TD, but is not detectable in axons (Figure 2A). Importantly, however, basal Puma protein levels are equivalent and its levels still rise during TD in the cell bodies of P53 knockout cultures, suggesting that P53 functions independently of regulating Puma levels. We further observed that the TD-associated increase in Caspase-3 cleavage (reflective of its enzymatic activation) proceeds normally in P53 knockout cell bodies. Remarkably, however, Caspase-3 cleavage in axons is dramatically attenuated in the P53 knockout (Figure 2A). Of note, the processing of Caspase-3 observed in wild type axons is sufficient to promote degeneration since Caspase-3 knockouts strongly protect axons in this paradigm (Simon et al., 2012). We also monitored cleavage of Caspase-3’s preferred substrate peptide ‘DEVD’ during TD. Consistent with our immunoblot data, we found no difference in TD-associated somatic DEVDase in P53 knockout cell bodies but a strong suppression of axonal DEVDase in P53 knockout axons (Figure 2B). That deletion of P53 blocks axonal but not somatic Caspase-3 activation during TD stands in contrast to the finding that deletion of Puma blocks both (Simon et al., 2016), reinforcing the conclusion that P53 functions independently of regulating of Puma expression.

Figure 2: Loss of P53 specifically impairs axonal caspase activation following TD.

(A) Wild type and P53 null (Trp53tm1Tyj/J) explants were subjected to TD. At the time of assay, axons and cell bodies were physically separated and independently lysed. The active form of Caspase-3 is indicated (black arrow). (B) Cell bodies and axons were independently lysed at 15hr of TD and DEVDase was measured. n=3 experiments. p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA.

How does P53 specifically affect axonal caspase activation? We first focused on P53’s canonical role as a transcription factor and examined its accumulation in the nucleus. Curiously, P53 did not clearly accumulate in the nucleus during TD, while doxorubicin, a genotoxic insult known to activate P53-dependent transcription, induced strong nuclear accumulation (Supplementary Figure 2A–C). We next explored a panel of genes whose neuronal expression is affected by P53 expression (Bowen et al., 2019), and while the mRNA abundance of some of these genes was altered by TD, these changes were unaffected by loss of P53 (Supplementary Figure 2D). Moreover, an additional panel of established P53 target genes was largely unaffected by TD (Supplementary Figure 2E). While we cannot rule out some P53-dependent transcriptional changes during TD, our data argue against a prominent role for their occurrence.

Interestingly, the baseline abundance of several mRNAs (including Puma and Bax) was decreased in P53 knockouts (Supplementary Figure 2D), but their fold induction upon TD was equivalent to wild type, suggesting that P53 may maintain baseline gene expression of some genes prior to TD. In the case of Puma however, the roughly ~50% reduction in basal mRNA levels does not impact basal Puma protein levels (Figure 2A). Moreover, the ~50% reduction in basal Bax mRNA levels is unlikely to contribute to the axon protective phenotype of P53 knockouts because Bax heterozygotes only display a minor (~30%) reduction in TD-induced axonal DEVDase compared to wild type (Supplementary Figure 2F). Therefore, differences in basal expression of P53 target genes are unlikely to account for phenotypic differences.

We next used mutational analysis to disrupt the transcriptional activity of P53 via its two N-terminal transactivation domains (TADs) (Figure 3A) (Brady and Attardi, 2010). The vast majority of P53’s transcriptional activity (>80%) has been attributed to TAD1 (Raj and Attardi, 2017). We cultured sensory neurons from mice harboring a conditional knock-in of two point mutations, L25Q and W26S, in TAD1 that severely compromise its transactivation-promoting activity (Brady et al., 2011). Homozygous P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26 mice are null for P53, owing to a floxed stop cassette inserted in the first intron. The presence of Cre recombinase removes this stop cassette and rescues the null allele with expression of the remaining P53 exons, harboring the two TAD1 mutations (Figure 3A). These P53 null neurons (P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26) were protected from degeneration upon TD, as described above using a distinct P53 null allele (Figure 1C). However, activation of the TAD1 mutated P53 allele via Cre (P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26 + Cre) reversed the protective phenotype of the null allele, increased DEVDase upon TD, and supported axon degeneration (Figure 3B–D). This result supports the view that TAD1’s transactivation activity is not essential for P53-dependent axon degeneration.

Figure 3: P53 promotes axon degeneration in the cytosol and requires its TAD2 domain.

(A) Domain and genomic structure of mouse P53 indicating the insertion of a LoxP-flanked transcriptional stop cassette and knock-in of two clusters of point mutations. Mutant alleles are P53 null due to the stop cassette, which is removed by Cre to enable expression of the mutant TAD alleles. (B-J) Sensory neurons from littermate embryos were subjected to TD. KO (1) denotes P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26; KO(2) denotes P53LSL−25,26,53,54/LSL−25,26,53,54; KO (null) denotes Trp53tm1Tyj/J. (B) Representative images from 25hr TD. Scale bar 100μm. (C) Quantification from (B) from n=3 experiments, p < 0.001. (D) Axonal DEVDase at 12hr TD. Quantification from n=4 experiments, p < 0.001. (E) Similar to (B) but performed in KO (2) and quantified in (F). n=3 experiments, p < 0.001. (G) Similar to (D) but performed in KO (2). n=4 experiments, p < 0.001. (H) KO (null) sensory neurons expressing either GFP or cytoplasmic P53. Representative images from 25hr, quantified in (I). n=3 experiments, p < 0.001. (J) Axonal DEVDase in KO (1) rescued with increasing levels of cytoplasmic P53. n=3 experiments, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

The TAD2 domain also contributes to transactivation of a smaller subset of genes by P53, a function that can be largely blocked by the F53Q and F54S mutations (Brady et al., 2011), while some genes are more strongly induced (Mello et al., 2017). However, F53 and F54 also lie in close proximity to N-terminal regions of P53 required for its cytoplasmic role in activating Bax (Follis et al., 2015). Thus, these mutations in TAD2 have the potential to affect both P53 transactivation activity and its interaction with Bax. We examined a mouse where Cre rescues a P53 null allele with a version of P53 harboring essential mutations in both TAD1 and TAD2 (Figure 3E–G) that abolishes residual transactivation seen in TAD1 mice. As with the other two P53 null alleles, these P53 null (P53LSL−25,26,53,54/LSL−25,26,53,54) neurons were protected from degeneration after TD (Figure 3E,F), but activation via Cre of P53 harboring the mutations in both TAD1 and TAD2 did not restore degeneration or DEVDase after TD (Figure 3E–G). Since activation of P53 with mutations in just TAD1 did restore degeneration, this implies a critical role of TAD2 residues F53 and F54 in degeneration.

Because TAD2 makes only a modest contribution to P53’s transcriptional activity, we next tested whether TAD2’s involvement might reflect instead a cytoplasmic role of P53 in interacting with Bax. We introduced a well-characterized mutation (K302A,R303A) in the C-terminal nuclear localization sequence of P53 that renders it constitutively cytoplasmic (hereafter ‘cytoplasmic P53’) into P53 null cells (O’Keefe et al., 2003). Expression of this variant rescued the defect in axon degeneration seen in neurons harboring the first P53 null mutation (Figure 3H,I). Further, expression of cytoplasmic P53 in the second null background (P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26) also restored axonal DEVDase activity to wild type levels, similar to the TAD1-only mutant (P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26 + Cre) (Figure 3J). Together these data support the view that cytoplasmic P53 is sufficient to restore axon degeneration when P53 has been removed.

Does endogenous P53 activate Bax in the cytoplasm? We visualized the subcellular distribution of P53 using immunostaining and observed a punctate distribution along the length of the axon, including co-localization with mitochondria. TD of the axon did not appear to markedly alter P53’s distribution, but given the thinness of axons it is possible that movements occurred within the diffraction limit (Figure 4A). In light of P53’s basal localization to mitochondria, we next sought to directly probe the relationship between P53 and activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. P53 is inhibited by the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL, preventing its pro-apoptotic interaction with Bax at mitochondria (Follis et al., 2018). In axons, Bcl-xL functions with family member Bcl-w to suppress Bax-dependent caspase activation and axon degeneration (Courchesne et al., 2011; Simon et al., 2016). Therefore, we reasoned that a role for P53 at the mitochondria may be revealed by antagonizing Bcl-xL. We applied ABT-737, a Bcl-xL/Bcl-w/Bcl-2 antagonist known to induce Bax- and Caspase-3-dependent axon degeneration (Simon et al., 2012). ABT-737 is a BH3 domain mimetic and competitively dissociates pro-apoptotic proteins that are normally bound by this domain (Oltersdorf et al., 2005) (Figure 4B). Importantly, axons from P53 null (P53LSL−25,26,53,54/LSL−25,26,53,54) and TAD1;TAD2 mutant (P53LSL−25,26,53,54/LSL−25,26,53,54 + Cre) explants were completely resistant to the caspase-activating effects of the drug (Figure 4C). This resistance is intrinsic to the axon because axons that were physically isolated from their cell bodies prior to drug treatment were equally resistant (Figure 4D). Rescuing the P53 null (P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26) with a TAD1-only mutant (P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26 + Cre) reversed the resistance phenotype (Figure 4E). Importantly, we also found a dose-dependent ability of cytoplasmic P53 to restore wild type levels of axonal DEVDase, elicited by ABT-737, in the null allele (Figure 4E). Further, the response of wild type axons to ABT-737 was suppressed by co-incubation with Pifithrin-μ, a small molecule that inhibits the association of P53 with mitochondria (Strom et al., 2006) (Figure 4F). Finally, expression of cytoplasmic P53 potentiated the response of wild type axons to ABT-737, an effect that was suppressed by co-incubation with Pifithrin-μ (Figure 4G). Together these data support a model in which cytoplasmic P53 is normally inhibited by Bcl-xL, but is released during apoptotic conditions to activate Bax, leading to caspase activation in axons.

Figure 4: P53 functions downstream of Bcl-xL inhibition to promote axonal caspase activation.

(A) Immunostaining of endogenous P53 (green) and mitochondria (mitoDsRed, red) in control axons and following 12hr TD. See also Supplementary Figure 2B. Scale bar 10μm. (B) Inhibition of Bcl-xL and Bcl-w is achieved using ABT-737. (C) Axonal DEVDase in the indicated cultures exposed to ABT-737 (12hr). n=3, p < 0.001. (D) Cell bodies were removed from wild type and KO (null) cultures expressing cytoplasmic NMNAT1, followed immediately by addition of ABT-737 (8hr) and assay of axonal DEVDase. n=3, p < 0.001 (E) Axonal DEVDase in KO(1) rescued with expression of cytoplasmic P53. n=3, p < 0.001. (F) Axonal DEVDase in wild type pre-treated with 50μM Pifithrin-μ, followed by ABT-737 (8hr) in the continued presence of Pifithrin-μ. n=4 experiments, p < 0.001. (G) Axonal DEVDase in wild type cultures expressing GFP or cytoplasmic P53 treated with Pifithrin-μ with and without ABT-737 (6hr). n=3. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001.

Discussion

Control of axon degeneration by Puma led us to focus our attention on P53. We found that sensory axon degeneration is strongly attenuated in P53 knockout neurons upon TD but that P53 functions through a cytoplasmic mechanism, distinct from regulating Puma.

In contexts where P53 promotes apoptosis, it often does so through transcriptional regulation of pro-apoptotic Noxa and/or Puma (Nakano and Vousden, 2001; Villunger et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2001), including in cortical neuron death triggered by ALS-associated toxic dipeptides (Maor-Nof et al., 2021). In sensory neurons, loss of Puma likewise potently protects axons from degeneration, accompanied by blockade of both somatic and axonal Caspase-3 activation (Maor-Nof et al., 2016; Simon et al., 2016), but we found that its relation to P53 is quite distinct. In P53 knockout sensory neurons, Puma levels rise normally, both at the mRNA and protein level. Further, while Caspase-3 activation is blocked in both axons and cell bodies in Puma knockouts, only axonal Caspase-3 activation is blocked in P53 knockouts. These results indicate that P53’s pro-degenerative role is independent of Puma induction. We note that a prior study reported that P53 contributes modestly to Puma induction upon TD, yet that P53 knockouts did not protect axons during TD (Maor-Nof et al., 2016). Our data are at odds with that study, as we document an axon protective phenotype in three distinct P53 null alleles and a phenotype in the P53 knockout that is distinct from that in the Puma knockout.

Beyond functioning independently of Puma transcription, several lines of evidence suggest that P53 functions independently of acute transcription more broadly during TD. First, we observe either no change in classical P53 target genes during TD, or changes that are independent of P53 status. While we cannot rule out some P53-dependent transcription associated with TD, and indeed detect TD-associated phosphorylation in the nucleus, these events are unlikely to be physiologically relevant to TD-associated degeneration (see below). Second, we fail to detect nuclear accumulation of P53 during TD, as is typically seen when P53 is transcriptionally active. Third, we show that physically isolated P53 knockout axons are resistant to acute caspase activation triggered by inhibition of Bcl-xL. Finally, we are able to rescue all of the P53 mutant phenotype with a P53 variant that is incapable of entering the nucleus to promote transcription.

Motivated by initial studies showing that expression of P53 caused apoptotic death even when nuclear import or protein synthesis is blocked (Caelles et al., 1994; Chipuk et al., 2003; Mihara et al., 2003), several groups have documented physical interactions between P53 and Bax (Chipuk et al., 2004; Follis et al., 2015; Tomita et al., 2006). Indeed, P53’s N-terminal transactivation domains, and to a lesser degree residues within its DNA binding domain, make critical contacts that activate Bax. Importantly, proline 47 within TAD2 gates Bax activity in the cytoplasm (Follis et al., 2015), and its close proximity to F53 and F54 may help resolve an apparent paradox, that TAD2 is required for P53’s activity in our assay without an apparent role for overt transactivation/transcription.

Is P53 itself an anterogradely-directed pro-degenerative factor? Puma, the key initiating protein in this pathway, is undetectable in axons in our assays, perhaps owing to its short half-life in sensory neurons (Simon et al., 2016). The phenotype of P53 knockouts – specific loss of axonal caspase activation – could fit with P53 being the anterogradely-directed factor, or with a role in its production, delivery, or function. However, our data are most consistent with P53 functioning as a critical effector of a distinct anterograde factor, since P53 is basally expressed in axons and its subcellular distribution appears – to the limits of our detection – unchanged by TD.

How, then, is the activity of cytoplasmic P53 regulated? Consistent with our ABT-737 data, structural studies show that cytoplasmic P53 can be inhibited by Bcl-xL, and further that Puma binding to Bcl-xL can disinhibit P53 to promote Bax activation (Follis et al., 2013). Therefore, rising Puma levels during TD could potentially disinhibit the pool of cytoplasmic P53 in close proximity to the cell body to initiate an anterograde propagation of caspase activity. P53 function is also heavily regulated by post-translational modifications (PTMs) (Hafner et al., 2019), including isomerization of proline 47 mentioned above (Follis et al., 2015). Anterograde control of PTMs could conceivably contribute to regulation of P53’s cytoplasmic activity.

The identification of an anterograde axon degeneration program raised the question of why a localized process would be controlled by the cell body and whether this process is simply an extension of somatic death. Our analysis of P53 knockout neurons indicates that axonal and somatic caspase activation are genetically separable, and that axon degeneration is a distinct process from somatic death. That P53 is a central integrator of multiple signaling pathways raises the prospect that cellular context may dictate its mode of action – transcriptional versus cytoplasmic – and that the extent of anterograde degeneration may be tuned through activation of one of these upstream pathways.

Limits of the study

Our study involves genetic deletions in mice, and therefore the phenotypes that we observe may be complicated by background mutations or genetic compensation by other genes. To minimize the likelihood that these events contribute to the phenotypes described, we have used multiple independent alleles of P53 and rescued mutant phenotypes by re-introducing P53. Our ability to detect the subcellular distribution of P53 is limited by the optical resolution of the wide-field microscopy that we employ. The width of the axon is essentially diffraction limited, and therefore in the absence of higher resolution techniques such as super-resolution microscopy or immune-electron microscopy, we are unable to firmly conclude whether axonal P53 moves to axonal mitochondria as axons degenerate.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Marc Tessier-Lavigne (tessier3@stanford.edu).

Materials Availability

Plasmids generated in this study are available directly from the authors.

Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate/analyze datasets/code.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mouse

Mice were used in accordance with IACUC-approved protocols at The Rockefeller University and Stanford University. Mice were housed in standard cages containing no more than five adult mice of the same gender. Timed-pregnant breedings involved a single adult female placed in a new cage with a single adult male until a vaginal plug was detected. The date of the plug is considered embryonic day (E) 0.5. In all cases, sensory neuron cultures were established from embryos of both genders harvested at E12.5 or 13.5 following timed-pregnant matings. For experiments where only wild type tissue is used, embryos were derived from the outbred CD1 line (IMSR Cat# CRL:022, RRID:IMSR_CRL:022). Direct comparisons between wild type and mutant strains are made between littermate controls following timed pregnant matings between parents heterozygous for that allele. The following mutant mouse lines were used in this study: P53null (Trp53tm1Tyj/J) (IMSR Cat# JAX:002101, RRID:IMSR_JAX:002101) (Jacks et al., 1994), P53tm4Att/J (P53LSL−25,26,53,54/LSL−25,26,53,54) (IMSR Cat# JAX:022070, RRID:IMSR_JAX:022070) (Brady et al., 2011), P53tm1Att/J (P53LSL−25,26/LSL−25,26) (IMSR Cat# JAX:022070, RRID:IMSR_JAX:022070) (Johnson et al., 2005), P63tm1Fmc (MGI Cat# 3695126, RRID:MGI:3695126) (Yang et al., 1999), P73tm1Fmc (MGI Cat# 2174786, RRID:MGI:2174786) (Yang et al., 2000), Baxtm1Sjk/J (IMSR Cat# JAX:002994, RRID:IMSR_JAX:002994) (Knudson et al., 1995).

Cell culture

Sensory neuron cultures were generated as previously described (Simon et al., 2016). Briefly, neurons were harvested from E12.5 or E13.5 embryos, dissociated and reaggregated at a density of 1.5×10^4 cells/μl. Neurons were plated in a 1 μl spot on dried plates coated sequentially with poly-D-lysine (20 μg/ml) and mouse natural laminin (10μg/ml), and grown in Neurobasal media containing 2% (v/v) B27 (Life Technologies), 0.45% (v/v) Glucose, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and supplemented with 50ng/mL NGF. as previously described (Simon et al., 2016). Cells were treated with mitotic inhibitor (10μM 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine and 10 μM uridine) the morning after plating. In cases where lentivirus was used, the virus was added on the evening following plating. All cultures were grown for 7–8 days prior to use.

METHOD DETAIL

Antibodies and Chemicals

The following antibodies were used. βIII Tubulin (Covance Cat# MMS-435P, RRID:AB_2313773), P53 (phospho S15) (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 9284, RRID:AB_331464), P53 (1C12) (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 2524, RRID:AB_331743), P53 (CM5) (Leica Biosystems Cat# P53-CM5P, RRID:AB_2744683), Puma (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 7467, RRID:AB_10829605), Caspase-3 (8G10) (Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 9665, RRID:AB_2069872), mCherry (1C51) (Abcam Cat# ab125096, RRID:AB_11133266).

The following chemicals and biochemical reagents were used: Pifithrin-μ (Selleck Chemicals, Catalog No.S2930), ABT-737 (Selleck Chemicals, Catalog No.S1002), Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay System (Promega, G8090), Nerve Growth Factor 2.5S (Promega, G5141).

Lentiviral production

Lentiviruses were produced in 293T cells and harvested and concentrated as previously described (Simon et al., 2016). The following lentiviral constructs used were previously reported: pLenti:GFP, pLenti:cytoplasmic-NMNAT1, pLenti:iCre-IRES-GFP (Simon et al., 2016). To generate cytoplasmic P53, a wild type mouse P53 (NM_011640) was PCR amplified from cDNA and cloned into the pLenti vector, followed by site-directed mutagenesis to introduce the K302A,R303A mutations. The pLV-mitoDsRed plasmid was obtained from Addgene (#44386).

Measurement of axonal DEVDase activity

Following the indicated treatments, cell bodies were removed from re-aggregated spot cultures using a razor, as previously described (Simon et al., 2016). Cell bodies placed directly into a tube containing Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent, diluted 50% with media. In parallel, half of the media was removed and replaced with an equal volume of Caspase-Glo 3/7. Following a one-hour lysis at room temperature, the contents of each well was transferred to an opaque 96-well plate and luminescence was determined using a plate reader.

Protein harvest and western blotting

Axons and cell bodies were independently harvested (see above) and directly lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 8M Urea, 10 % (w/v) SDS, 10mM sodium EDTA, 50 mM DTT, supplemented with Brilliant Blue G. Axon or cell body material from between 5 and 10 spots were pooled for each condition. Protein samples were resolved on Tris-HCl gradient gels (Bio-Rad) and blotted using standard techniques. Proteins were detected using enhanced chemilumescence (Pierce).

Immunohistochemistry

Cultures were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde in PBS, blocked for at least one hour at room temperature in 3% donkey serum in PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X-100 (PBS-X). Slides were incubated in primary antibody overnight in blocking solution at room temperature. Fluorescent secondary antibodies were added at 1:500 in 3% donkey serum in PBS-X. Slides were imaged on either a Nikon Eclipse 90i wide-field fluorescence microscope, or an Eclipse Ti2 microscope equipped with a Plan Apo 60× 1.4NA objective (used to visualize axonal P53 in Figure 4A).

Real-time PCR measurement

Following treatments, a minimum of 8 re-aggregated spot cultures were lysed directly on the culture plates and pooled using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were normalized by total RNA abundance and cDNA was synthesized using the Superscript III reverse transcriptase (ThermoFisher # 18080051) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Real time PCR experiments were performed in biological triplicate in 96 well plates using the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (ThermoFisher # 4369016) and expression of each gene was normalized to the expression of GAPDH.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The magnitude of axon degeneration was determined as previously described (Simon et al., 2016). Quantification of P53 levels in the nucleus was performed by measuring the fluorescence intensity of P53 immunostaining in the nucleus (defined by co-localization with Hoechst stain) and in the cytoplasm, and normalizing each value to the area of the region of interest quantified. The ratio of the normalized nuclear to normalized cytoplasmic P53 intensities is reported for each condition. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. Statistical details of experiments can be found in each figure legend. All data are reported as mean +/− SEM. In all cases, n refers to the number of independent experiments performed.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-βIII Tubulin | Covance | Cat# MMS-435P, RRID:AB 2313773 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-P53 (phospho S15) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9284, RRID:AB_331464 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-P53 (1C12) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2524, RRID:AB 331743 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-P53 (CM5) | Leica Biosystems | Cat# P53-CM5P, RRID:AB 2744683 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-Puma | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 7467, RRID:AB 10829605 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Caspase-3 (8G10) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9665, RRID:AB 2069872 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-mCherry (1C51) | Abcam | Cat# ab125096, RRID:AB_11133266 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| pLenti::GFP | (Simon et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pLenti::iCre-IRES-GFP | (Simon et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pLenti::cytoplasmic NMNAT1 | (Simon et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pLenti::mouse cytoplasmic P53 (K302A,R303A) | This work | N/A |

| pLV-mitoDsRed | (Kitay et al., 2013) | Addgene #44386, RRID:Addgene_443 86 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Pifithrin-μ | Selleck Chemicals | Cat. #S2930 |

| ABT-737 | Selleck Chemicals | Cat. #S1002 |

| Nerve Growth Factor 2.5S | Promega | Cat. #G5141 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay System | Promega | Cat. #G8090 |

| Superscript III reverse transcriptase | Thermofisher | Cat. # 18080051 |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix | Thermofisher | Cat. #4369016 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| 293FT | Thermofisher | Cat. # R70007 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| CD1 | Charles River Laboratories | IMSR Cat# CRL:022, RRID:IMSR_CRL:022 |

| P53null (Trp53tm1Tyj/J) | (Jacks et al., 1994) | IMSR Cat# JAX:002101, RRID:IMSR_JAX:00 2101 |

| P53tm4Att/J (P53LSL−25,26,53,54/ LSL−25,26,53,54) | (Brady et al., 2011) | IMSR Cat# JAX:022070, RRID:IMSR_JAX:02 2070 |

| P53tm1Att/J (P53LSL−25,26/ LSL−25,26) | (Johnson et al., 2005) | IMSR Cat# JAX:022070, RRID:IMSR_JAX:02 2070 |

| P63tm1Fmc | (Yang et al., 1999) | MGI Cat# 3695126, RRID:MGI:3695126 |

| P73tm1Fmc | (Yang et al., 2000) | MGI Cat# 2174786, RRID:MGI:2174786 |

| Baxtm1Sjk/J | (Knudson et al., 1995) | IMSR Cat# JAX:002994, RRID:IMSR_JAX:00 2994 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Apaf1 (Mm01223701_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Pmaip1 (Noxa) (Mm00451763_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Bax (Mm00432051_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Plk2 (Mm00446917_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Siva1 (Mm00834449_g1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Lars2 (Mm00467701_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Scn4b (Mm01175562_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Dusp15 (Mm00521352_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Bbc3 (Puma) (Mm00519268_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Trp53 (P53) (Mm01731290_g1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Mdm2 (Mm0123138_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Snai2 (Mm00441531_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Btg2 (Mm00476162_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Pde3a (Mm0047958_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Polk (Mm01282564_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Cdkn1a (P21) (Mm00432448_m1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1) | Thermofisher | Cat. #: 4331182 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLenti::GFP | (Simon et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pLenti::iCre-IRES-GFP | (Simon et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pLenti::cytoplasmic NMNAT1 | (Simon et al., 2016) | N/A |

| pLenti::mouse cytoplasmic P53 (K302A,R303A) | This work | N/A |

| pLV-mitoDsRed | (Kitay et al., 2013) | Addgene #44386, RRID:Addgene_443 86 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Prism 8 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

Highlights:

Sensory axon degeneration is a genetically separable process from cell body death

Loss of P53 specifically blocks axonal but not somatic caspase activation

P53 functions in the axonal cytosol downstream of Bcl-xL to drive axon degeneration

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank members of the Tessier-Lavigne laboratory for comments. Aaron Gitler and Maya Maor-Nof shared unpublished observations. This work was supported by NIH grants to MT-L (R01NS089786-06) and LDA (R35CA197591). DJS was supported in part by the Whitehall Foundation, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests: MT-L is a director of Denali Therapeutics and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Other authors declare no competing interests.

References Cited

- Aloyz RS, Bamji SX, Pozniak CD, Toma JG, Atwal J, Kaplan DR, and Miller FD (1998). p53 is essential for developmental neuron death as regulated by the TrkA and p75 neurotrophin receptors. J Cell Biol 143, 1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen ME, McClendon J, Long HK, Sorayya A, Van Nostrand JL, Wysocka J, and Attardi LD (2019). The Spatiotemporal Pattern and Intensity of p53 Activation Dictates Phenotypic Diversity in p53-Driven Developmental Syndromes. Dev Cell 50, 212–228 e216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady CA, and Attardi LD (2010). p53 at a glance. J Cell Sci 123, 2527–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady CA, Jiang D, Mello SS, Johnson TM, Jarvis LA, Kozak MM, Kenzelmann Broz D, Basak S, Park EJ, McLaughlin ME, et al. (2011). Distinct p53 transcriptional programs dictate acute DNA-damage responses and tumor suppression. Cell 145, 571–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caelles C, Helmberg A, and Karin M (1994). p53-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcriptional activation of p53-target genes. Nature 370, 220–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD, and Green DR (2005). PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science 309, 1732–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Droin NM, Newmeyer DD, Schuler M, and Green DR (2004). Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science 303, 1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk JE, Maurer U, Green DR, and Schuler M (2003). Pharmacologic activation of p53 elicits Bax-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcription. Cancer Cell 4, 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne SL, Karch C, Pazyra-Murphy MF, and Segal RA (2011). Sensory neuropathy attributable to loss of Bcl-w. J Neurosci 31, 1624–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont P, Leu JI, Della Pietra AC 3rd, George DL, and Murphy M (2003). The codon 72 polymorphic variants of p53 have markedly different apoptotic potential. Nat Genet 33, 357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follis AV, Chipuk JE, Fisher JC, Yun MK, Grace CR, Nourse A, Baran K, Ou L, Min L, White SW, et al. (2013). PUMA binding induces partial unfolding within BCL-xL to disrupt p53 binding and promote apoptosis. Nat Chem Biol 9, 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follis AV, Llambi F, Kalkavan H, Yao Y, Phillips AH, Park CG, Marassi FM, Green DR, and Kriwacki RW (2018). Regulation of apoptosis by an intrinsically disordered region of Bcl-xL. Nat Chem Biol 14, 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follis AV, Llambi F, Merritt P, Chipuk JE, Green DR, and Kriwacki RW (2015). Pin1-Induced Proline Isomerization in Cytosolic p53 Mediates BAX Activation and Apoptosis. Mol Cell 59, 677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, and Kroemer G (2009). Cytoplasmic functions of the tumour suppressor p53. Nature 458, 1127–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner A, Bulyk ML, Jambhekar A, and Lahav G (2019). The multiple mechanisms that regulate p53 activity and cell fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20, 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt Y, Rowan S, Shaulian E, Vousden KH, and Oren M (1995). Induction of apoptosis in HeLa cells by trans-activation-deficient p53. Genes Dev 9, 2170–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, and Weinberg RA (1994). Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol 4, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TM, Hammond EM, Giaccia A, and Attardi LD (2005). The p53QS transactivation-deficient mutant shows stress-specific apoptotic activity and induces embryonic lethality. Nat Genet 37, 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitay BM, McCormack R, Wang Y, Tsoulfas P, and Zhai RG (2013). Mislocalization of neuronal mitochondria reveals regulation of Wallerian degeneration and NMNAT/WLD(S)-mediated axon protection independent of axonal mitochondria. Hum Mol Genet 22, 1601–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson CM, Tung KS, Tourtellotte WG, Brown GA, and Korsmeyer SJ (1995). Bax-deficient mice with lymphoid hyperplasia and male germ cell death. Science 270, 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME, and George DL (2004). Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat Cell Biol 6, 443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maor-Nof M, Romi E, Sar Shalom H, Ulisse V, Raanan C, Nof A, Leshkowitz D, Lang R, and Yaron A (2016). Axonal Degeneration Is Regulated by a Transcriptional Program that Coordinates Expression of Pro- and Anti-degenerative Factors. Neuron 92, 991–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maor-Nof M, Shipony Z, Lopez-Gonzalez R, Nakayama L, Zhang YJ, Couthouis J, Blum JA, Castruita PA, Linares GR, Ruan K, et al. (2021). p53 is a central regulator driving neurodegeneration caused by C9orf72 poly(PR). Cell 184, 689–708 e620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko ND, Zaika A, and Moll UM (2000). Death signal-induced localization of p53 protein to mitochondria. A potential role in apoptotic signaling. J Biol Chem 275, 16202–16212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello SS, Valente LJ, Raj N, Seoane JA, Flowers BM, McClendon J, Bieging-Rolett KT, Lee J, Ivanochko D, Kozak MM, et al. (2017). A p53 Super-tumor Suppressor Reveals a Tumor Suppressive p53-Ptpn14-Yap Axis in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 32, 460–473 e466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, Petrenko O, Chittenden T, Pancoska P, and Moll UM (2003). p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell 11, 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FD, Pozniak CD, and Walsh GS (2000). Neuronal life and death: an essential role for the p53 family. Cell Death Differ 7, 880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano K, and Vousden KH (2001). PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell 7, 683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe K, Li H, and Zhang Y (2003). Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of p53 is essential for MDM2-mediated cytoplasmic degradation but not ubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol 23, 6396–6405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, Armstrong RC, Augeri DJ, Belli BA, Bruncko M, Deckwerth TL, Dinges J, Hajduk PJ, et al. (2005). An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 435, 677–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj N, and Attardi LD (2017). The Transactivation Domains of the p53 Protein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldiner O, and Yaron A (2015). Mechanisms of developmental neurite pruning. Cell Mol Life Sci 72, 101–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh SY, Ikeda M, Taya Y, and Prives C (1997). DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell 91, 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DJ, Pitts J, Hertz NT, Yang J, Yamagishi Y, Olsen O, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, and Tessier-Lavigne M (2016). Axon Degeneration Gated by Retrograde Activation of Somatic Pro-apoptotic Signaling. Cell 164, 1031–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DJ, Weimer RM, McLaughlin T, Kallop D, Stanger K, Yang J, O’Leary DD, Hannoush RN, and Tessier-Lavigne M (2012). A caspase cascade regulating developmental axon degeneration. J Neurosci 32, 17540–17553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom E, Sathe S, Komarov PG, Chernova OB, Pavlovska I, Shyshynova I, Bosykh DA, Burdelya LG, Macklis RM, Skaliter R, et al. (2006). Small-molecule inhibitor of p53 binding to mitochondria protects mice from gamma radiation. Nat Chem Biol 2, 474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita Y, Marchenko N, Erster S, Nemajerova A, Dehner A, Klein C, Pan H, Kessler H, Pancoska P, and Moll UM (2006). WT p53, but not tumor-derived mutants, bind to Bcl2 via the DNA binding domain and induce mitochondrial permeabilization. J Biol Chem 281, 8600–8606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villunger A, Michalak EM, Coultas L, Mullauer F, Bock G, Ausserlechner MJ, Adams JM, and Strasser A (2003). p53- and drug-induced apoptotic responses mediated by BH3-only proteins puma and noxa. Science 302, 1036–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel KS, and Parada LF (1998). Sympathetic neuron survival and proliferation are prolonged by loss of p53 and neurofibromin. Mol Cell Neurosci 11, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson RT, Tabin C, Sharpe A, Caput D, Crum C, et al. (1999). p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 398, 714–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Walker N, Bronson R, Kaghad M, Oosterwegel M, Bonnin J, Vagner C, Bonnet H, Dikkes P, Sharpe A, et al. (2000). p73-deficient mice have neurological, pheromonal and inflammatory defects but lack spontaneous tumours. Nature 404, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, and Vogelstein B (2001). PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell 7, 673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze datasets/code.