Abstract

A growing body of research points to the efficacy of participatory methods in decreasing rates of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use and other risky behaviors among youth. However, to date, no systematic review of the literature has been conducted on Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) for youth substance use prevention. This review draws on the peer-reviewed literature on YPAR in the context of youth substance use prevention published from January 1, 1998 through April 30, 2018. We summarize (1) the published evidence regarding YPAR for youth substance use prevention; (2) the level of youth engagement in the research process; (3) the methodologies used in YPAR studies for youth substance use prevention; and (4) where more research is needed. In all, we identified 15 unduplicated peer-reviewed, English-language articles that referenced YPAR, Community Based Participatory Research, youth, and substance use prevention. We used Reliability-Tested Guidelines for Assessing Participatory Research Projects to assess the level of youth engagement in the research process. Our findings indicated that youth participation in research and social action resulted in increased community awareness of substance use and related solutions. This supports the premise of youth participation as an agent of community change by producing community-specific substance use data and prevention materials. Identified weaknesses include inconsistent levels of youth engagement throughout the research process, a lack of formalized agreements between youth and researchers with regard to project and data management, and a lack of outcome evaluation measures for assessing YPAR for youth substance use prevention.

Keywords: Youth Substance Use, Youth Participatory Action Research, Community Based Participatory Research, Systematic Review, Adolescent

Youth substance use and misuse continues to be a public health concern of epidemic proportions (Mack, 2012). Early initiation of substance use is associated with negative health, social, and behavioral outcomes later in life, including physical and behavioral health problems (Mack, 2012; Newcomb & Locke, 2005). According to the Monitoring the Future Survey (MTF), in 2017, annual marijuana prevalence among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders increased significantly by 1.3 percentage points to 23.9% (Johnston et al., 2018). Further, lifetime prevalence, annual prevalence, 30-day prevalence, and daily prevalence of alcohol use showed little or no change (Johnston et al., 2018). Alarmingly, this is the first year that no decrease in prevalence was demonstrated, and may herald the end of the long-term decline in youth alcohol use (Johnston et al., 2018). Similarly, prevalence of use of any illicit drug other than marijuana remained steady in 2017 (Johnston et al., 2018).

These findings point to a need for innovative approaches for prevention, including youth engagement in research and public health programming (Ozer, 2017). Youth participatory action research (YPAR) has received growing attention in public health and related fields for its potential in augmenting prevention efforts related to alcohol, tobacco, or other drug (ATOD) use. Ozer describes YPAR as an innovative, equity-focused approach for promoting adolescent health and well-being that draws on the expertise of youth as they conduct research and improve conditions that support healthy development (Ozer, 2017).

With roots in the pedagogy of Brazilian-born education reformer Paulo Freire (Freire, 1996), YPAR is a form of participatory action research (PAR) that provides youth with the opportunity to study social problems affecting their lives and to determine actions to solve these problems (Cammarota & Fine, 2008). PAR is an approach that engages researchers and participants in collective, self-reflective inquiry so they can understand themselves and the world around them, and improve upon their circumstances (Livingston, 2017). Livingston describes PAR as combining two separate research concepts: participation – active involvement of “subjects” in the research process; and action – defining social problems and solving them (Livingston, 2017). Further, PAR recognizes the social, political, and structural origins of health and the disproportionate impact of substance use and related problems on disenfranchised groups (Freire, 1996; Trask, 1987).

YPAR also is similar in to youth-led community-based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR most closely resembles the tenants of PAR while emphasizing the scientific rigor of conventional research (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). According to Israel and colleagues, CBPR is a collaborative partnership approach to research that equitably involves community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process (Israel et al., 1998). The research process is defined as inception of the research question, data collection and analysis, dissemination and/or application of the results (Israel et al., 1998). Partners contribute their expertise and share responsibilities and ownership of the research. This collaborative process thus increases the understanding of a given phenomenon, which can be incorporated into action to enhance the health and well-being of community members (Israel et al., 1998).

YPAR is distinct from PAR and CBPR in that it is youth-led, as opposed to being adult-led with or about youth (Cammarota & Fine, 2008). Youth learn how to conduct research (using surveys, focus groups, and photovoice, among other methods), effectively becoming youth researchers and advocates for change (Jason & Glenwick, 2016). Further, YPAR emphasizes the development and strengthening of collective efficacy (or collective empowerment) among youth involved in the research, which enables them to engage in social action for change. Youth advocate for change based on evidence from their research, and engage in social action in their schools, communities, and at the policy level, which in turn influences their attitudes and behaviors (Cammarota & Fine, 2008).

YPAR can contribute to substance use research as an ideal approach to ensure cultural-grounding and culture-as-intervention in health promotion programs targeting youth, particularly as more public health research and health behavior interventions emphasize culture over individual level strategies to achieve sustainable change resulting in positive health outcomes (Airhihenbuwa, Ford, & Iwelunmor, 2014). Further as youth are embedded in complex environments, participatory methods are ideal for public health researchers and practitioners targeting the ecological contexts in which substance use occurs (Golden, McLeroy, Green, Earp, & Lieberman, 2015). PAR/CBPR/YPAR approaches have been shown to successfully decrease rates of ATOD use and other risky behaviors among at-risk youth (Kulbok et al., 2015; Romero, 2016). However, while there is a growing body of research on YPAR (Cammarota & Fine, 2008; Ozer, 2017; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017), existing research using YPAR for youth substance use prevention has not been systematically evaluated.

The purpose of this review is to identify and describe YPAR studies in the context of youth substance use prevention research. We documented targeted substances, participant descriptions, objectives, overarching participatory approaches, methodologies used, youth outcomes, community outcomes, and reported pit falls. Specifically, we had four overarching objectives: (1) To summarize the published evidence regarding YPAR for youth substance use prevention; (2) To articulate the level of youth engagement in the research process; (3) To summarize the methodologies used in YPAR studies for youth substance use prevention; and (4) To synthesize where more research is needed.

Methods

The current study is guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), used for the transparent reporting of systematic reviews (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009).

Sources

Inclusion criteria included peer-reviewed, English-language articles published from January 1, 1998 through April 30, 2018 that referenced YPAR, PAR, CBPR, youth, and substance use prevention. We included articles on YPAR interventions/programs/projects for youth substance use prevention; youth-led PAR or CBPR projects; and studies addressing substance use prevention as a primary or secondary outcome. All included studies described research that was youth-led (versus adult-led or in partnership with adults).

Articles inconsistent with the inclusion criteria or which were editorial, historical or theoretical in nature were excluded. We excluded articles on adult-led interventions with youth collaborators and articles or other publications from non-peer reviewed sources. For example, we excluded articles where youth were used to validate or test an intervention if that intervention was not originally conceived by and developed by youth.

Search Strategy

To identify references we conducted a search across PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, EMBASE and Google Scholar online databases, followed by an analysis of the text contained in the title, abstract, and index terms of retrieved articles. Depending on the search engine, we used MeSH heading, keyword, and topic searches. Our search included terms associated with the study population (separated by OR): ‘adolescent’ or ‘adolescence’ or ‘youth’ or ‘teen’, AND terms associated with the approach: ‘youth participatory action research’ or ‘community-based participatory research’ or ‘participatory action research’, AND terms associated with the outcome: ‘substance use’ or ‘substance abuse’ or ‘drug abuse’ or ‘drug prevention’ or ‘drug dependence’ or ‘drug use’ or ‘underage drinking’ or ‘alcohol’ or ‘alcohol use’ or ‘alcohol misuse’ or ‘alcoholism’ or ’marijuana’ or ‘cannabis use’ or ’marijuana use’ or ‘opioid’ or ‘opioid misuse’ or ‘opioid use’ or ‘injection drug use’ or ‘injection drug’ or ‘amphetamine’ or ‘amphetamine use’ or ‘ illicit drug’ or ‘illicit drug use’ or ‘tobacco’ or ‘tobacco use’. We then carefully reviewed reference lists from all articles that met the inclusion criteria for additional studies for potential review.

Study Selection

Two authors (ESV, IS) independently inspected all titles and abstracts according to the inclusion criteria and eliminated duplicates. We recorded author, journal, and year of publication from each manuscript that met inclusion criteria. Where the two authors disagreed, they met to discuss and, if possible, reach a consensus. They met once to resolve eight disagreements and were able to reach consensus on six. Judgment was referred to a third reviewer (LV) for the remaining two studies.

Risk of Bias (Quality Assessment): Level of Youth Engagement

The Reliability-Tested Guidelines for Assessing Participatory Research Projects (Mercer et al., as cited in Minkler & Wallerstein, 2011) were adapted to assess the level of youth engagement in each stage of the participatory research process: participants and the nature of their involvement (i.e., participants’ appropriateness for the project); participants’ role in shaping the purpose and scope of the research (i.e., inception of the research question and development of the study design); their role in research implementation and context (i.e., data collection and analysis); and their role in the dissemination of research outcomes (i.e., dissemination/application of the results [social action]). The guidelines define participatory research as systematic inquiry, with the collaboration of those affected by the issue being studied, for the purposes of education and of taking action or effecting change (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2011). The guidelines are meant to assess proposed projects; however, we used them to assess completed projects described in the articles. For the purposes of this review, we adapted the guidelines by assessing whether the article met or did not meet each guideline. We excluded two guidelines within Shaping the Purpose and Scope of the Research from our scoring as they fell out of the scope of the objectives of this literature review and synthesis. Specifically, the eliminated guidelines did not assess engagement in the research process. While further description of the guidelines is outside of the scope of this article, the complete guidelines can be found at Mercer et al., as cited in Minkler & Wallerstein, 2011). We searched for the presence of each of the domains in all projects described within selected articles and reported the results of this deductive thematic analysis (Table 2).

Table 2:

Youth Participation in the Research Process

| Ager | Berg | Brazg | Diamond | Helm | Jardine | Lee 2013 | Lee 2017 | Maglajlić | Petteway | Pinsker | Poland | Ross | Tanjasiri | Wilson | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants & the Nature of their Involvement | Are the intended users (may include users, beneficiaries, and/or stakeholders) of the research described adequately enough to assess their representation in the project? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Is the mix of participants included in the research process sufficient to consider the needs of the project’s intended users? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Is effort made to address barriers to participation in the research process by intended users who might otherwise tend to be underrepresented? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Has provision been made to build trust between researchers and intended users participating in the research process? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Do the researchers and intended users participating in the research process have a formal or informal agreement (verbal or written) regarding management of the project? | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Role in shaping the purpose and scope of the research | Was (were) the research question(s) developed (or refined) through a collaborative process between researchers and intended users? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Has the proposed research project applied the knowledge and experience of intended users in conceptualizing and/or designing the research? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Does the proposed research project provide for mutual learning among intended users and researchers? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Role in research implementation and context | Does the proposed research project apply the knowledge and experience of intended users in the implementation of the research? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Does the proposed research project provide intended users participating in the research process with opportunity to learn about research (whether or not the intended users choose to take that opportunity)? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Does the proposed research project provide researchers with opportunity to learn about user perspectives on the issue(s) being studied? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Do the researchers and intended users participating in the research process have a formal or informal agreement (verbal or written) regarding mutual decision making about potential changes in research methods or focus? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Does the proposed research project provide intended users with opportunity to participate in planning and executing the data collection (whether or not the intended users choose to take that opportunity)? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Does the proposed research project provide intended users with opportunity to participate in planning and/or executing the analysis (whether or not the intended users choose to take that opportunity)? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Are plans to involve intended users in interpreting the research findings sufficient to reflect knowledge of the particular context and circumstances in the interpretation? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Role in the dissemination of research outcomes | Does the proposed research project reflect sufficient commitment by researchers and intended users participating in the research process to action (for example, social, individual, and/or cultural) following the (learning acquired through) research? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Do the researchers and intended users engaged in the research process have a formal or informal agreement (verbal or written) for acknowledging and resolving in a fair and open way any differences in the interpretation of research results? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Do the researchers and intended users engaged in the research process have a formal or informal agreement (verbal or written) regarding ownership and sharing of the research data? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Do the researchers and intended users engaged in the research process have a formal or informal agreement (verbal or written) regarding feedback of research results to intended users? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Do the researchers and intended users engaged in the research process have a formal or informal agreement (verbal or written) regarding the dissemination (and/or translation or transfer) of research findings? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Does the proposed research project provide intended users with opportunity to participate in dissemination of project findings to other intended users and researchers (whether or not the intended users choose to take that opportunity)? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ‘X | X | |||

| Is there sufficient provision for assistance to intended users to indicate a high probability of research results being applied? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Does the proposed research project plan for sustainability in relation to the purpose of the research (for example, by fostering collaboration between intended users and resource providers, funding sources, policymakers, holders of community assets, and the like)? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

Results

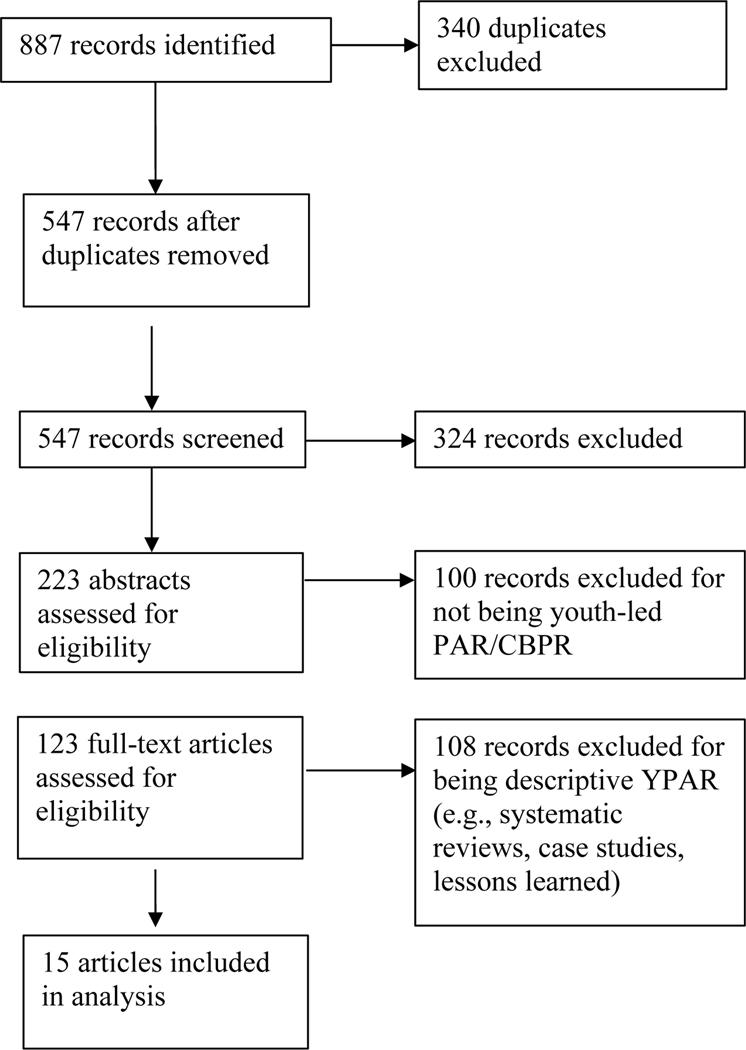

We identified 887 article abstracts and screened them for duplicates (Figure 1). A total of 547 original abstracts were retained and 340 duplicates deleted. Of the retained abstracts, 324 were excluded due to search engine misclassification (i.e., those unrelated to YPAR, CBPR, or substance use prevention). The remaining 223 article abstracts were screened for youth-led CBPR as follows: 14 described community-placed research (i.e., traditional research conducted in/about a community but without community participation); 16 described research that was community-partnered but for which the community did not conduct the research; 30 described research that was CBPR for adults about adults; and 39 articles described research that was CBPR that involved youth but was not youth-led (e.g., adult-led with or about youth). Next, the full texts of the remaining 123 articles were screened for substance use intervention studies involving YPAR, among which 108 were excluded because they were descriptive/review articles on YPAR (i.e., other systematic reviews unrelated to substance use, case studies, and lessons learned articles focused on elements other than interventions of interest). Finally, 15 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review. The projects described in these articles varied considerably with regard to targeted substances, participant descriptions, objectives ,participatory approaches, methods, youth outcomes, community outcomes, and reported pitfalls (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study Selection Flow Chart

Table 1:

YPAR Studies for Substance Use Prevention

| Author, Year | Targeted Substance | Participant Description | N | Objectives | Participatory Approach | Methods | Youth Outcomes | Community Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ager et al., 2008 | ATOD | Inner-city, African American, ages 10–12 | 7 | To prevent or reduce youth drug abuse through utilizing and enhancing community capacities to develop a drug prevention video | None listed | Video development | Participants improved their drug (t = −3.61, p < .05) and video (t = −3.63, p < .05) knowledge; learned research skills; engaged with community; participated in the development of drug education content tailored to their community | Drug-education content tailored to community |

| Berg et al., 2009 | ATOD | African American, Latino, ages 14–16 | 114 | To reduce and/or delay onset of drug and sexual risk in urban adolescents | PAR | Mixed methods | Intervention youth shifted to believing that fewer peers were using drugs (p =049); youth approval of peer drug use decreased (p = .084) and educational expectations increased (p = .091). Individual behavioral level outcomes: alcohol use and frequency of marijuana use, number of sex partners decreased over time. Majority graduated from high school. | Increase in social cohesion; increase in community level self-efficacy; increase in social action |

| Brazg et al., 2011 | ATOD | Upper middle-income suburban community, ages 14–18 | 9 | To engage high school youth in a community-based assessment of adolescent substance use and abuse | PAR | Photovoice | Increased dialogue between youth and adult community members about adolescent substance use; produced traveling exhibit of the data that is now owned by the community and the youth participants. | Increased dialogue between youth and adult community members about adolescent substance use; enhanced community-level data; Photovoice data that motivated community action |

| Diamond et al., 2009 | ATOD | African American, Latino, ages 14–20 | 41 | Strengthen protective factors and reduce risk factors for alcohol and other substance use among high school age youth by addressing multiple factors at the individual, peer, community and city level | Participatory Intervention Model | Media-based drug prevention intervention | Produced intervention “Leadership and Craft Development Training Program”; produced 5 Xperience shows, volume One Xperience CD and CD release show; recruited and trained Xperience artists who could effectively deliver drug prevention messages to their peers via song, dance and spoken word based on their own experiences, and who could model drug-free behavioral values and norms; cooperation with media | Developed youth partnerships with neighborhood-based community organizations; reached several thousands of youth with ads, information booths, website, promotional items and CDs, heard about the program from friends |

| Helm et al., 2015 | ATOD | Native Hawaiian, ages 12–18 | 10 | To guide the development of a Native Hawaiian model of drug prevention | PAR, Positive Youth Development | Photovoice | Youth increased perceived value of cultural values, practices, beliefs, protocols, and disciplines; youth engaged as leaders and role models in their community | Received enhanced community-level data needed to develop the foundation of an efficacious prevention program from the perspective of rural Hawaiian youth |

| Jardine & James, 2012 | Tobacco | Native Dene, ages 14–18 | 10 | To better understand: what youth know and understand about tobacco use; how they vie w tobacco use in their community; and what influences their decisions to start smoking or not to start smoking | PAR, Hart’s Ladder of Participation | Interviews | Produced book “Youth Voices on Tobacco”, and distributed to all students at two schools; increased leadership skills and research skills | Raised awareness of tobacco use and helped both the youth researchers and the community to consider possible steps towards changing to healthier lifestyle choices; shift in view to youth as resources |

| Lee et al., 2013 | Tobacco | Southeast Asian, ages 15–26 | 15 | To describe environmental aspects of tobacco use among Southeast Asian refugees in the U.S. | PAR | Survey, Photovoice | Raised youth awareness of tobacco products and tobacco use in their environment. | Received enhanced community-level data |

| Lee et al., 2017 | Tobacco | Southeast Asian, ages 15–24 | 9 | To engage youth in critical analysis of how tobacco us impacts their community | PAR | Photovoice, Observations | Youth connected smoking behaviors they observed at their school with low student morale and student officials’ lack of engagement regarding students’ tobacco use. | School-youth dialogue about low student morale and student officials’ lack of engagement regarding students’ tobacco use |

| Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006 | ATOD | ages 13–19 | 75 | To develop a communication strategy for the prevention of HIV/AIDS in Bosnia Herzegovina; to increase the capacity of young people to become involved in developing knowledge and practices that support their well-being | PAR | Mixed methods | Prevention strategy developed: recommendation to develop a nation-wide, school-based participatory peer education program using interactive group-based interactive workshops.Cooperation with the media using talk shows, TV advertisements, billboards, music | |

| Petteway et al., 2018 | Tobacco | Minority, ages 10–14 | 14 | To (1) elucidate how youth from a high-tobacco-burden community perceive/interact with their local tobacco environment; (2) train youth as active change agents for tobacco-related community health; and (3) improve intergenerational understandings of tobacco use/impacts within the community | CBPR | Photovoice | Youth presented their findings and what they learned through the process to community; developed Youth Tobacco Advisory Council | Instrumental in establishing a more dynamic and open communication between city agencies, council members, community residents, and members of the CEASE collaborative |

| Pinsker et al., 2017 | Tobacco | Somali, ages 13–17 | 65 | To develop a culturally appropriate tobacco prevention intervention targeted toward Somali youth in Minneapolis, Minnesota. | CBPR | Video development | Produced videos targeting factors found to influence youth tobacco use among East African youth including social norms, peer influence, culture/religion, misinformation and acceptability of tobacco use | Received drug-education content tailored to community; contributed to youth collaborations with ongoing community programs |

| Poland et al., 2002 | ATOD | Street-involved, ages not specified | 6 | To develop and implement a harm reduction program for street involved youth using a participatory process | PAR | Focus group, interviews | Produced a 20-minute video to illustrate issues and strategies for drug-related harm reduction that was distributed to agencies in Toronto who serve street-involved youth. Increased social cohesion among participants. | Received drug-education content tailored to community |

| Ross, 2011 | Tobacco | Minority, Ages 15–18 | 20 | To engage youth in a community-based tobacco assessment | Positive Youth Development | GIS, Observations, Counts | Engaged with and provided tobacco prevention recommendations to community leaders, city council, local health committee, city solicitor, policy makers; worked with a senator to write a bill | Received enhanced community-level data and increased youth engagement at the policy level |

| Tanjasiri et al., 2011 | Tobacco | Asian American and Pacific Islander, Ages 14–18 | 32 | To empower Asian American and Pacific Islander youth to identify and understand environmental characteristics associated with tobacco use in four AAPI communities in California and Washington | CBPR | Photovoice | Presented to tobacco control advocates and city council; had opportunities to collaborate with more youth, networking, followed by skills building sessions on data dissemination (oral presentation, video, web-based formats) | Received enhanced community-level data |

| Wilson et al., 2008 | ATOD | Elementary school students (multiple groups) | 122 | To identify and build youths’ capacities and strengths as a means of ultimately decreasing rates of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use and other risky behavior | CBPR, Positive Youth Development | Photovoice | Groups developed their own measures for success of this projects; increased social action at the school-level (e.g., awareness campaigns about school conditions; school behavior campaigns, cleanup projects, projects to improve school spirit). | Increased youth engagement at the school-level |

Targeted Substance(s)

Seven articles listed tobacco as the targeted substance (Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Petteway et al., 2018; Pinsker et al., 2017; Ross, 2011; Tanjasiri et al., 2011). Eight articles reportedly targeted general substance use or ATOD (Ager et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2009; Brazg et al., 2011; Diamond et al., 2009; Helm et al., 2015; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Poland et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2008).

Participant Descriptions

The projects described in the 15 articles varied with regard to target populations. Fourteen articles involved youth of vulnerable backgrounds (i.e., rural, indigenous, street involved, refugee, conflict survivors) (Ager, Parquet, & Kreutzinger, 2008; Berg, Coman, & Schensul, 2009; Diamond et al., 2009; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee, Lipperman-Kreda, Saephan, & Kirkpatrick, 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Petteway, Sheikhattari, & Wagner, 2018; Ross, 2011; Tanjasiri, Lew, Kuratani, Wong, & Fu, 2011; Wilson, M. Minkler, S. Dasho, N. Wallerstein, & A. C. Martin, 2008), rural youth (Helm et al., 2015), urban youth (Ager et al., 2008), street-involved youth (Poland, Tupker, & Breland, 2002), LGBTQ youth (Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006), refugee youth (Pinsker et al., 2017), and survivors of conflict (Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006)). One article did not describe participants as having any kind of vulnerability (Brazg, Bekemeier, Spigner, & Huebner, 2011).

Eleven articles engaged youth of color (e.g., African American (Ager et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2009; Diamond et al., 2009), Latino (Berg et al., 2009; Diamond et al., 2009), Native (Helm et al., 2015; Jardine & James, 2012), Southeast Asian (Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017), Somali (Pinsker et al., 2017), Asian American and Pacific Islander (Tanjasiri et al., 2011). Study populations engaged a range of ages (i.e., ages 10–24). Most participants were 10–18 years of age. Only one article studied elementary school children (Wilson et al., 2008). Studies were conducted in the United States, except two were conducted in Canada and one was conducted in Bosnia Herzegovina.

Sample sizes varied greatly across articles. Seven articles had sample sizes of 10 or fewer participants (Ager et al., 2008; Brazg et al., 2011; Helm et al., 2015; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2017; Poland et al., 2002). Three articles had sample sizes between 15–20 participants (Diamond et al., 2009; J. P. Lee et al., 2013; Petteway et al., 2018; Ross, 2011). Five articles reported projects with multiple cohorts, with total sample sizes ranging from 32–122 participants (Berg et al., 2009; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Pinsker et al., 2017; Tanjasiri et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2008).

Objectives

Articles reported varying objectives to achieve their overall goal of youth substance use prevention. Six articles reported aiming to conduct a community assessment of youth substance use (Brazg et al., 2011; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Ross, 2011; Tanjasiri 3t al., 2011). Four articles sought to develop an intervention or program for substance use prevention (Helm et al., 2015; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Pinsker et al., 2017; Poland et al., 2002). Four articles reported goals related to building youth or community capacity (Ager et al., 2008; Diamond et al. 2009, Petteway et al., 2018; Wilson et a., 2008). One article conveyed the objective was to reduce and/or delay onset of substance use in youth (Berg et al., 2009).

Participatory Approaches

A number of different participatory project designs were reported. Salient approaches included PAR (n=7) (Berg et al., 2009; Brazg et al., 2011; Helm et al., 2015; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013: Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Poland et al., 2002) CBPR (n=4) (Petteway et al., 2018; Pinsker et al., 2017; Tanjasiri et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2008), Hart’s Ladder of Participation (n=1) (Jardine & James, 2012), and the participatory intervention model (PIM) (Diamond et al., 2009). One article did not mention a participatory approach (Ager et al., 2008).

Roger Hart’s Ladder of Participation emphasizes meaningful youth participation where youth initiate projects or programs and share decision making with adults. It describes eight escalating degrees of participation, ranging from non-participation at the lowest rungs (e.g., manipulation, decoration, and tokenism) to true participation at the top rungs of the ladder (e.g., provision of information by youth, youth-initiated shared decisions with adults) (Shier, 2001). The participatory intervention model (PIM) is a methodology for grounding interventions in the ongoing life of communities, by involving community stakeholders and targeted populations in each stage of the intervention development process (Nastasi et al. 2000).

There are a number of overlapping elements across participatory approaches, and many articles used more than one approach. For example, three articles reported using Positive Youth Development (PYD) (Helm et al., 2015; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008). PYD is an intentional approach that recognizes, utilizes, and enhances young people’s strengths, rather than focusing on correcting, curing, or treating them for maladaptive tendencies or so-called disabilities (Damon, 2004). PYD is a framework that is compatible with PAR/CBPR, but PYD does not require a research component.

Methods

Articles described the use of a variety of research methods. All articles reported providing research methods or skills development training followed by a youth-led research project or intervention. Photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1994, 1997) was the most common method (n=6) (Brazg et al., 2011; Helm et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Petteway et al., 2018; Tanjasiri et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2007). Four articles reported traditional qualitative methods including focus groups, one-on-one interviews, community observations, and community surveys (Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Poland et al., 2002). Two articles reported using both Photovoice and traditional qualitative methods (Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017). One article reported mixed methods projects with multiple cohorts (Berg et al., 2009). One article reported a project in which youth counted and documented temporary tobacco advertisements, and analyzed Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping data of tobacco stores in their neighborhood (Ross, 2011).

Three articles reported skills development training for the purposes of developing an intervention. Two articles reported youth-led video development for substance use prevention (Ager et al., 2008; Pinsker et al., 2017). One article described the “Leadership and Craft Development Training Program” to train youth to produce original works of art to be either recorded on a compilation CD or displayed at a live “drug free” CD release show (Diamond et al., 2009). All articles described some type of action plan (e.g., reaching policy makers), social action activity (e.g., community presentation), or deliverable (e.g., community-tailored tobacco prevention video) as the culminating element of the participatory project.

Outcomes for Youth

Articles reported a number of positive effects of youth involvement in YPAR projects on substance use indicators. Participating youth increased their knowledge about tobacco (Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Petteway et al., 2018; Pinsker et al., 2017; Ross, 2011; Tanjasiri et al., 2011), alcohol, and other substances (Ager et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2009; Brazg et al., 2011; Diamond et al., 2009; Helm et al., 2015; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Poland et al., 2002). Ten articles presented results from YPAR projects that identified influential factors for substance use in their communities, thereby increasing their knowledge and awareness of these issues at the community level (Ager et al., 2008; Brazg et al., 2011; Helm et al., 2015; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Petteway et al., 2018; Pinsker et al., 2017; Ross, 2011; Tanjasiri et al., 2011). Other outcomes included decreased approval of peer drug use (Berg et al., 2009), increased dialogue between youth and adult community members about youth substance use (Brazg et al., 2011), and decreased alcohol use and frequency of marijuana use over time (Berg et al., 2009).

Articles noted that youth involvement in YPAR encouraged skill development among youth. Youth developed research skills, including photography (Brazg et al., 2011; Helm et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017; Petteway et al., 2018; Tanjasiri et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2007), qualitative data collection and analysis (Poland et al., 2002), video development, editing, and production (Ager et al., 2008; Pinsker et al., 2017), marketing, media, and art design (Diamond et al., 2009), research methods (Berg et al., 2009; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Ross, 2011), group-identified action plan development (Wilson et al., 2008), decision making (Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006), and teamwork (Ross, 2011). Researchers also reported that youth developed their leadership skills through their engagement in YPAR projects. Specifically, their involvement in YPAR provided them with opportunities to interact with decision-makers and thus positioned them as leaders and role models in their communities (Helm et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017; Petteway et al., 2018; Ross, 2011; Tanjasiri et al., 2011), while also connecting them with public speaking and networking opportunities (e.g., conferences, presentations) (Berg et al., 2009; Helm et al., 2015; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Petteway et al., 2018; Ross, 2011; Tanjasiri et al., 2011).

According to the articles, fundamental to the success of YPAR was the development and strengthening of collective efficacy (or collective empowerment) among these groups of youth, which enabled them to engage in social action. All articles reported that youth either contributed to development of action plans or conducted action-oriented activities, which involved raising critical awareness among their peers, schools, adults, and/or communities through social media, workshops, strategic meetings, and community presentations.

YPAR projects provided youth opportunities to engage in advocacy and policy change for substance use prevention. For example, Ross (2011) reported that their project provided youth with the opportunity to work with a senator to write a bill to limit the marketing and sale of tobacco to minors. Other articles reported advocacy activities including the development of collective action plans and projects designed to change public norms and promote social advocacy around youth issues at the school, community, organizational, and policy levels (Berg et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2008).

Outcomes for Communities

Communities received substance use-specific data, programs, and materials tailored to their communities by youth living and interacting in these environments. For example, one article reported that their YPAR project developed a community-specific prevention strategy, including the recommendation to develop a nation-wide, school-based participatory peer education program (Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006). Another article reported that the community received enhanced community-level data needed to develop the foundation of a prevention program from the perspective of rural Hawaiian youth (Helm et al., 2015).

YPAR projects helped to re-shape community perceptions of youth, effectively shifting the discourse from youth as problems to youth as resources and agents of change. For example, Petteway, Sheikhattari, and Wagner (2018) stated that their project led to the development of a youth tobacco advisory council, and was instrumental in establishing a more dynamic and open communication between city agencies, council members, community residents, and members of the tobacco prevention collaborative. Overall, articles commented on the complex interaction between learning, adult support and facilitation, research action and creating, and affirming positive attitudes towards youth involvement in the community.

YPAR projects involved youth in community awareness and educational campaigns for substance use prevention. Articles reported cooperation with the media using talk shows, TV advertisements, billboards, and music (Diamond et al., 2009; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006). Youth also had the opportunity to disseminate findings to other youth through a peer to-peer education program that resulted from YPAR projects (Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006), and through workshops and strategic meetings (Lee et al., 2017). Another project reportedly reached several thousands of youth through ads, information booths, a website, promotional items, and friends (Diamond et al., 2009).

Reported Pitfalls

Articles noted a number of pitfalls over the course of the YPAR projects. Pitfalls included youth (Petteway et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2008) and staff turnover (Petteway et al., 2018) and limited time to complete deliverables (Jardine & James, 2012; Wilson et al., 2008). Limited resources and budget also posed some challenges for YPAR projects (Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011). YPAR projects, like most researcher or funder-sponsored projects, often faced challenges related to sustainability and achieving long-term impact (Petteway et al., 2018).

Level of Youth Engagement

According to participatory research scholars, true participatory research involves community members from inception to dissemination (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2011). We determined that the articles varied in the degree researchers engaged youth in the research process (Table 2).

Participants and the nature of their involvement

All articles described the youth to assess their representation in the project. Most articles described provisions to build trust between researchers and youth (n=12) (Ager et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2009; Diamond et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Petteway et al., 2018; Pinsker et al., 2017; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008). Fewer articles described making efforts to address barriers to participation by underrepresented youth (n=8) (Ager et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2009; Diamond et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2017; Petteway et al., 2018; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008), or having a formal/informal agreement regarding management of the project (n=5) (Diamond et al., 2009; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008).

Shaping the purpose and scope of the research

All articles described providing for mutual learning among youth and researchers. However, researchers were less likely to involve youth in the development of the research question (n=7) (Berg et al., 2009; Diamond et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Pinsker et al., 2017; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008), or consult with them or involve them in the research design (n=7) (Berg et al., 2009; Diamond et al., 2009; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Pinsker et al., 2017; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008).

Research implementation and context

All articles described work involving youth in research implementation, providing youth with the opportunity to learn about research, and permitting researchers to learn about youth’s perspectives on the research topic. Nearly all research engaged youth in data analyses and sufficiently involved youth in interpretation of research findings (n=13) (Ager et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2009; Brazg et al., 2011; Diamond et al., 2009; Helm et al., 2015; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Petteway et al., 2018; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008). Fewer articles described having a formal or informal agreement regarding mutual decision-making about potential changes in research methods or focus (n=8) (Berg et al., 2009; Diamond et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008).

Nature of the research outcomes

All articles reflected commitment to social, individual, and/or cultural action by both the researchers and youth participating in the research process, but fewer described having a formal or informal agreement for acknowledging differences in result interpretation (e.g., youth have a different perspective of the findings than the researcher) (n=9) (Diamond et al., 2009; Helm et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Petteway et al., 2018; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008). All articles described a formal or informal agreement (verbal or written) regarding ownership and sharing of the research data (n=15). Most articles reported providing feedback of research results to youth (n=13) (Ager et al., 2008; Brazg et al., 2011; Diamond et al., 2009; Helm et al., 2015; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Petteway et al., 2018; Pinsker et al., 2017; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008), and involving youth in the dissemination of research findings (n=14) (Ager et al., 2008; Brazg et al., 2011; Diamond et al., 2009; Helm et al., 2015; Jardine & James, 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Petteway et al., 2018; Pinsker et al., 2017; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Tanjasiri et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2008). Most articles described plans directed at sustainability in relation to the purpose of the research (e.g., by fostering collaboration between youth and youth-serving agencies, funding sources, policymakers) (n=12) (Ager et al., 2008; Brazg et al., 2011; Diamond et al., 2009; Helm et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2017; Maglajlić & Tiffany, 2006; Petteway et al., 2018; Pinsker et al., 2017; Poland et al., 2002; Ross, 2011; Wilson et al., 2008).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to review current evidence for YPAR studies in the context of youth substance use prevention research We summarize (1) the published evidence regarding YPAR for youth substance use prevention; (2) the level of youth engagement in the research process; (3) the methodologies used in YPAR studies for youth substance use prevention; and (4) where more research is needed.

We systematically examined the existing YPAR studies aiming to prevent youth substance use, their targeted substances, participant descriptions, objectives, participatory approaches, methodologies, youth outcomes, community outcomes, and pitfalls, as well as the role of youth in the research process. Most projects described in the articles targeted tobacco and ATOD as part of their prevention efforts. We identified articles involving a diverse set of target populations. Almost all articles described studies that engaged vulnerable youth in the participatory process. The literature supports YPAR as an appropriate approach to engage youth of color who may not yet feel comfortable with written/verbal expression (Anyon, Bender, Kennedy, & Dechants, 2018; Cammarota & Fine, 2008; Ozer, 2017). Articles reported multiple objectives intended to help meet their universal goal of youth substance use prevention, including developing community assessments, building youth and community capacity, and developing interventions/programs. This review identified articles describing the development of substance use prevention interventions using a YPAR approach, as well as articles describing YPAR projects in which the participatory method (e.g., Photovoice) served as the intervention itself. Youth engagement was facilitated by the participatory approaches employed by the studies, including CBPR, PAR, YPAR, PIM, and Hart’s Ladder of Participation.

The 15 studies utilized a variety of research methods and/or skills development, the most frequent of which were photovoice, qualitative methods, and video development. Digital storytelling tools like photovoice and video development in particular are consistent with YPAR and CBPR principles that emphasize empowerment, individual and community strengths, mutual learning, and balancing research and action (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2011). The photovoice process in particular is touted as a means to link youth with their community through culture and leadership (Helm & Kanoelani Davis, 2017). Further, using YPAR, qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups feature an individual’s or group’s feelings, views, and patterns and minimize control or manipulation from the researcher (MacDonald, 2012). Articles described using the findings from the research methods to develop some type of action plan (e.g., reaching policy makers), social action activity (e.g., community presentation), or deliverable (e.g., tobacco prevention video) as the culminating element of the participatory project.

Youth and communities experienced a number of positive outcomes as a result of their participation in YPAR substance use prevention projects. Youth learned about substance use, developed research skills, developed collective efficacy, and participated in advocacy and policy change. Communities benefitted from YPAR projects in numerous ways, including receipt of community-tailed substance use-specific data, programs and materials, positively shifted community perceptions of youth to resources and agents of change, and increased community awareness through educational substance use prevention campaigns. Our findings coincide with other reviews of participatory research with youth regarding to benefits of YPAR for youth and communities (Anyon et al., 2018; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017).

We assessed youth engagement in the research process using the Reliability-Tested Guidelines for Assessing Participatory Research Projects by Mercer et al. (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2011). Articles varied with regard to the level of youth engagement. We found that more than half of studies reported that youth were generally more engaged in later phases of the research (e.g., dissemination of the results). Fidelity to the YPAR approach is such that youth are involved in every step of the research process (Cammarota & Fine, 2008). When a researcher identifies a problem, generates the research question, and develops the study design, this can create power imbalances, misinterpret youth voices, or create a research environment where youth play a trivial role (Cammarota & Fine, 2008; Shier, 2001).

Research involving youth from inception to dissemination was able to engage youth in substance use prevention at multiple levels. For example, one study that involved youth in the development of the research question and study design found effects at multiple levels, including individual level behavioral change (i.e., decreased alcohol use and frequency of marijuana use), increased social cohesion among participants, improved peer norms (i.e., youth shifted to believing that fewer peers were using drugs and approval of peer drug use decreased, educational expectations increased), and increased community level self-efficacy (i.e., increase in social action) (Berg et al., 2009). Increased youth engagement also resulted in opportunities for engagement with policy makers.

We also identified areas for improvement. With regard to youth engagement in the research process, programs could have enhanced power sharing and equitable decision-making between researchers and youth. Several studies did not report established formal or informal agreements with youth at varying phases of the YPAR process, including agreements regarding management of the project and its data, or potential changes in research methods. We acknowledge that some of these agreements may have been implicit in nature or simply not reported; however, formalized agreements promote trust and encourage power sharing (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2011). As such, it is critical that researchers balance time and resources to expand the roles of youth beyond their role as solely a data source, and emphasize equitable power distribution, in order to promote the youth voice and enhance project outcomes (Cammarota & Fine, 2008).

Another area for improvement within YPAR for youth substance use prevention is outcome evaluation. All articles identified by this review reported youth substance use prevention as one of their primary or secondary outcomes. However, articles varied widely with regard to their outcome measures, likely due to the wide range of reported objectives (i.e., intervention development, community assessment, capacity building). Most articles did not report if and how outcome data were collected or analyzed, the data limitations, or how other researchers might replicate or confirm these findings. Only one article reported more proximal individual level behavioral outcomes measures for youth involved in the project (i.e., frequency of substance use) (Berg et al., 2009). The majority of articles used more distal measures for evaluating YPAR (versus substance use) including measures for peer norms and collective efficacy (e.g., social action) and community engagement. Many articles reported their outcomes as the deliverables resulting from the projects (e.g., videos, photovoice data, interactions with decision-makers, research skill development). Using more proximal measures for substance use would help to assess how involvement in YPAR changes the substance use behaviors of the youth involved. Further, no articles reported long-term outcomes for youth involved in the projects. We recommend follow-up with youth to determine how involvement in YPAR impacts substance use-related outcomes, including improvements in educational attainment (e.g., high school graduation), health behaviors (e.g., substance use), and interpersonal outcomes (e.g., domestic violence).

Strengths and Limitations

This review has numerous strengths. Importantly, we used PRISMA guidelines to systematically examine YPAR for substance use prevention. We believe this review adds valuable insight to the expanding literature on YPAR and its potential applications. The review is not without limitations. First, the exclusion of articles from non-peer-reviewed sources, book chapters, and masters and doctoral theses may have eliminated some important and influential examples of YPAR for youth substance use prevention. We also limited the search to articles published in English, and may have missed some relevant contributions in other languages. Publication bias poses considerable limitations given that studies with limited or negative findings likely remained unpublished, resulting in a bias toward effective or successful YPAR projects. We identified studies using a comprehensive list of search terms; however, the search terms could have limited the scope of identified articles. We may have missed studies that could be considered YPAR because of the use of specific labels particular to the field, thus limiting the generalizability of findings. Relatedly, the authors acknowledge that a single research program may occur over multiple years and is represented in numerous peer- reviewed articles and other forms of dissemination. A single article may aim to highlight only one phase of the project, rather than all phases of a project. For example, issues like formal and informal agreements may nbnot be addressed in a particular article or dissemination activity. It is possible that these research projects in fact address all of these components, but did not report them in the retained article. As a result, the articles that were identified, screened, and retained in this review are not meant to be comprehensive representations of all aspects of YPAR for youth substance use prevention.

Implications for Research

Research on YPAR for youth substance use prevention remains sparse. Therefore, additional research focused on using YPAR methods in substan ce use research with this population is needed. While several articles included in this review discussed how youth involvement enhanced or informed community-level data collection efforts, additional research should focus on specific community outcomes including practice and policy changes. Several articles reported successful YPAR or CBPR outcomes for curriculum or intervention development. Further research should engage youth in the development and testing of youth substance use prevention programs. This review also found limited use of evaluation measures. Future studies should include evaluation measures for substance use at both the individual/behavioral level and community level as a means to measure impact of YPAR programs.

Conclusions

YPAR provides youth with opportunities to develop research and leadership skills, while fostering consciousness about social issues of concern, including youth substance use. Critical consciousness can propel youth towards action to inform substance use related research, policy change, and intervention development. Future research should prioritize more fully engaging youth in every step of the research process and establish more formalized agreements between youth and researchers with regard to project and data management. The addition of outcome measures for assessing YPAR for youth substance use prevention is also needed. However, there is high promise for YPAR frameworks and methods to enhance youth substance use prevention. Building on collective strength and community assets, these studies show that youth can collaborate with researchers to collect data, develop materials and programs, and promote social change in their communities, schools, and neighborhoods. As youth are embedded in complex environments where identities(s), culture(s) and developmental processes are fluid, YPAR is an ideal approach to ensure cultural-grounding and culture-as-intervention in health promotion programs (Airhihenbuwa, Ford, & Iwelunmor, 2014). Further, with the rapid change of technology, culture and globalism, these methods are ideal for public health researchers and practitioners aiming for responsiveness to the ecological contexts in which substance misuse occurs (Golden, McLeroy, Green, Earp, & Lieberman, 2015).

Acknowledgments

The study described in this manuscript was funded by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Services Award, Individual Predoctoral Fellowship [PA-16–309] by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health; the Program in Migration and Health – California Endowment, UC Berkeley; and the Center for Border Health Disparities, Arizona Health Sciences, University of Arizona.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Salerno Valdez, University of Arizona, Health Promotion Sciences. 1295 N Martin Ave, Tucson, AZ 85724.

Iva Skobic, University of Arizona, Health Promotion Sciences. 1295 N Martin Ave, Tucson, AZ 85724.

Luis Valdez, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, Arnold House, Amherst, MA 01003.

David O Garcia, University of Arizona, Health Promotion Sciences. 1295 N Martin Ave, Tucson, AZ 85724.

Josephine Korchmaros, University of Arizona, Southwest Institute for Research on Women. 181 S. Tucson Blvd. 101 Tucson, AZ 85716.

Sally Stevens, University of Arizona, Southwest Institute for Research on Women. 181 S. Tucson Blvd. 101 Tucson, AZ 85716.

Samantha Sabo, Northern Arizona University, Center for Health Equity Research. PO Box 4064, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011-4065.

Scott Carvajal, University of Arizona, Health Promotion Sciences. 1295 N Martin Ave, Tucson, AZ 85724.

References

*Indicates 15 articles included in this review.

- *Ager R, Parquet R, & Kreutzinger S. (2008). The youth video project: An innovative program for substance abuse prevention. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 8(3), 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Ford CL, & Iwelunmor JI (2014). Why culture matters in health interventions: lessons from HIV/AIDS stigma and NCDs. Health Education & Behavior, 41(1), 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anyon Y, Bender K, Kennedy H, & Dechants J. (2018). A systematic review of youth participatory action research (YPAR) in the United States: methodologies, youth outcomes, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior, 1090198118769357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum F, MacDougall C, & Smith D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(10), 854–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Berg M, Coman E, & Schensul JJ. (2009). Youth action research for prevention: A multi-level intervention designed to increase efficacy and empowerment among urban youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43(3–4), 345–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brazg T, Bekemeier B, Spigner C, & Huebner CE (2011). Our community in focus: the use of photovoice for youth-driven substance abuse assessment and health promotion. Health Promotion Practice, 12(4), 502–511. doi: 10.1177/1524839909358659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota J, & Fine M. (2008). Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Damon W. (2004). What is positive youth development? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- *Diamond S, Schensul J, Snyder L, Bermudez A, D’alessandro N, & Morgan D. (2009). Building Xperience: a multilevel alcohol and drug prevention intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43(3–4), 292–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (revised). New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Golden S, McLeroy K, Green L, Earp JA, & Lieberman L. (2015). Upending the Social Ecological Model to Guide Health Promotion Efforts Toward Policy and Environmental Change. Health Education & Behavior, 42(1_suppl), 8S–14S. doi. 10.1177/1090198115575098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, & Kanoelani Davis H. (2017). Challenges and lessons learned in implementing a community-academic partnership for drug prevention in a Native Hawaiian community. Puerto Rico health sciences journal, 36(2), 101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Helm S, Lee W, Hanakahi V, Gleason K, McCarthy K, & Haumana. (2015). Using Photovoice with youth to develop a drug prevention program in a rural Hawaiian community. American Indian Alask Native Mental Health Research, 22(1), 1–26. doi: 10.5820/aian.2201.2015.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, & Becker A. (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jardine C, & James A. (2012). Youth researching youth: benefits, limitations and ethical considerations within a participatory research process. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 71(0), 1–9. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason L, & Glenwick D. (2016). Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L, Miech R, O’Malley P, Bachman J, Schulenberg J, & Patrick M. (2018). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Retrieved from: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/142406/Overview2017%20FINAL.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Kulbok PA, Meszaros PS, Bond DC, Thatcher E, Park E, Kimbrell M, & Smith-Gregory T. (2015). Youths as partners in a community participatory project for substance use prevention. Family & community health, 38(1), 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lee J, Lipperman-Kreda S, Saephan S, & Kirkpatrick S. (2013). Tobacco environment for Southeast Asian American youth: results from a participatory research project. Journal of Ethnic Substance Abuse, 12(1), 30–50. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.759499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lee J, Pagano A, Kirkpatrick S, Le N, Ercia A, & Lipperman-Kreda S. (2017). Using photovoice to develop critical awareness of tobacco environments for marginalized youth in California. Action Research, 1476750317741352. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston W. & Perkins A. (2018). Participatory action research (PAR) research: critical methodological considerations. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 18(1), 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald C. (2012). Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13(2), 34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mack A. (2012). Adolescent Substance Use: America’s# 1 Public Health Problem. Year Book of Psychiatry and Applied Mental Health, 2012, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- *Maglajlic R, & Tiffany J. (2006). Participatory action research with youth in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Community Practice, 14(1–2), 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, & Wallerstein N. (2011). Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nastasi B, Varjas K, Schensul S, Silva K, Schensul J, & Ratnayake P. (2000). The participatory intervention model: A framework for conceptualizing and promoting intervention acceptability. School Psychology Quarterly, 15(2), 207–232. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb M, & Locke T. (2005). Health, social, and psychological consequences of drug use and abuse. In Epidemiology of Drug Abuse (pp. 45–59): Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer E. (2017). Youth-Led Participatory Action Research: Overview and Potential for Enhancing Adolescent Development. Child Development Perspectives, 11(3), 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- *Petteway R, Sheikhattari P, & Wagner F. (2019). Toward an Intergenerational Model for Tobacco-Focused CBPR: Integrating Youth Perspectives via Photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 20(1), 67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pinsker E, Call K, Tanaka A, Kahin A, Dar S, Ganey A, . . . Okuyemi K. (2017). The Development of Culturally Appropriate Tobacco Prevention Videos Targeted Toward Somali Youth. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 11(2), 129–136. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2017.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Poland B, Tupker E, & Breland K. (2002). Involving street youth in peer harm reduction education. The challenges of evaluation. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 93(5), 344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A. (2016). Youth-Community Partnerships for Adolescent Alcohol Prevention:“We Can’t Do It Alone”. In Youth-Community Partnerships for Adolescent Alcohol Prevention (pp. 1–17). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- *Ross L. (2011). Sustaining Youth Participation in a Long-term Tobacco Control Initiative: Consideration of a Social Justice Perspective. Youth & Society, 43(2), 681–704. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shamrova D, & Cummings C. (2017). Participatory action research (PAR) with children and youth: An integrative review of methodology and PAR outcomes for participants, organizations, and communities. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 400–412. [Google Scholar]

- Shier H. (2001). Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Children & Society, 15(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- *Tanjasiri S, Lew R, Kuratani D, Wong M, & Fu L. (2011). Using Photovoice to assess and promote environmental approaches to tobacco control in AAPI communities. Health Promotion Practice, 12(5), 654–665. doi: 10.1177/1524839910369987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask H. (1987). From a Native daughter. In: Martin C. (Ed.). The American Indian and the problem of history. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. & Burris M. (1994). Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Education Quarterly, 21(2), 171–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. & Burris M. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N, Dasho S, Martin AC, Wallerstein N, Wang C, & Minkler M. (2007). Engaging young adolescents in social action through photovoice: The youth empowerment strategies (YES!) project. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 27(2), 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- *Wilson N, Minkler M, Dasho S, Wallerstein N, & Martin AC (2008). Getting to social action: The youth empowerment strategies (YES!) project. Health Promotion Practice, 9(4), 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]