Abstract

Kanamycin A is an aminoglycoside antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces kanamyceticus and used against a wide spectrum of bacteria, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biosynthesis of kanamycin involves an oxidative deamination step catalyzed by kanamycin B dioxygenase (KanJ), thereby the C2’ position of kanamycin B is transformed into a keto group upon release of ammonia. Here, we present for the first time, structural models of KanJ with several ligands, which along with the results of ITC binding assays and HPLC activity tests explain substrate specificity of the enzyme. The large size of the binding pocket suggests that KanJ can accept a broad range of substrates, which was confirmed by activity tests. Specificity of the enzyme with respect to its substrate is determined by the hydrogen bond interactions between the methylamino group of the antibiotic and highly conserved Asp134 and Cys150 as well as between hydroxyl groups of the substrate and Asn120 and Gln80. Upon antibiotic binding, the C terminus loop is significantly rearranged and Gln80 and Asn120, which are directly involved in substrate recognition, change their conformations. Based on reaction energy profiles obtained by density functional theory (DFT) simulations, we propose a mechanism of ketone formation involving the reactive FeIV = O and proceeding either via OH rebound, which yields a hemiaminal intermediate or by abstraction of two hydrogen atoms, which leads to an imine species. At acidic pH, the latter involves a lower barrier than the OH rebound, whereas at basic pH, the barrier leading to an imine vanishes completely.

Keywords: aminoglycoside, deamination, protein structure, reaction mechanism, α-ketoglutarate

Introduction

Aminoglycoside antibiotics are an important group of drugs with a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity. They are naturally produced by various species of bacteria, mainly Streptomyces [1] and Micromonospora [2]. Historically, streptomycin isolated in 1943 was the first characterized drug from the aminoglycoside group. Later, among products of bacterial fermentation a series of other compounds of similar structure and antimicrobial properties was identified [3]. Nowadays, more than 20 aminoglycosides of natural origin are used in clinical treatment [4–6]. Additionally, these natural antibiotics serve as precursors for the chemical synthesis of their derivatives that often show new or enhanced activity. The latter is very much in demand in an age of growing bacterial antibiotic resistance [7–9].

One of the main global health problems is the increasing drug resistance of new M. tuberculosis strains and severe side effects of antituberculosis (anti-TB) therapy. According to medical reports, about 20% of TB cases worldwide are caused by strains resistant to at least one of the anti-TB drugs used in the first or second line of treatment [10]. Therefore, development of new antimicrobial therapies is of paramount importance, and in this respect, understanding the mechanism of biosynthesis of aminoglycosides may help to develop an effective combinatorial synthesis of new antibiotics.

The antimicrobial effect of aminoglycosides is related to the presence of a unique aminocyclitol moiety in their structure, most commonly 2-deoxystreptamine (2-DOS), substituted at the C4, C5, or C6 positions with various sugars [11]. The 2-DOS core of clinically important aminoglycosides is doubly substituted at positions C4 and C5, for example, neomycin, ribostamycin, and paromomycin, or at positions C4 and C6, for example, kanamycin, gentamicin, and tobramycin. The representative of the latter group, kanamycin, is an important drug with strong activity against Gram-positive bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis [1].

Natural kanamycin, produced by Streptomyces kanamyceticus, is a mixture of 4 compounds, among which the most abundant is kanamycin A, whereas the additional constituents are kanamycin B, C [12], and X [13]. All variants have the same kanosamine ring bound at the C6 position of the 2-DOS moiety but differ in amino-sugars tethered to C4, which is 6-amino-6-deoxy-D-glucose in kanamycin A, neosamine in kanamycin B, D-glucosamine in kanamycin C, and D-galactopyranose in kanamycin X [14].

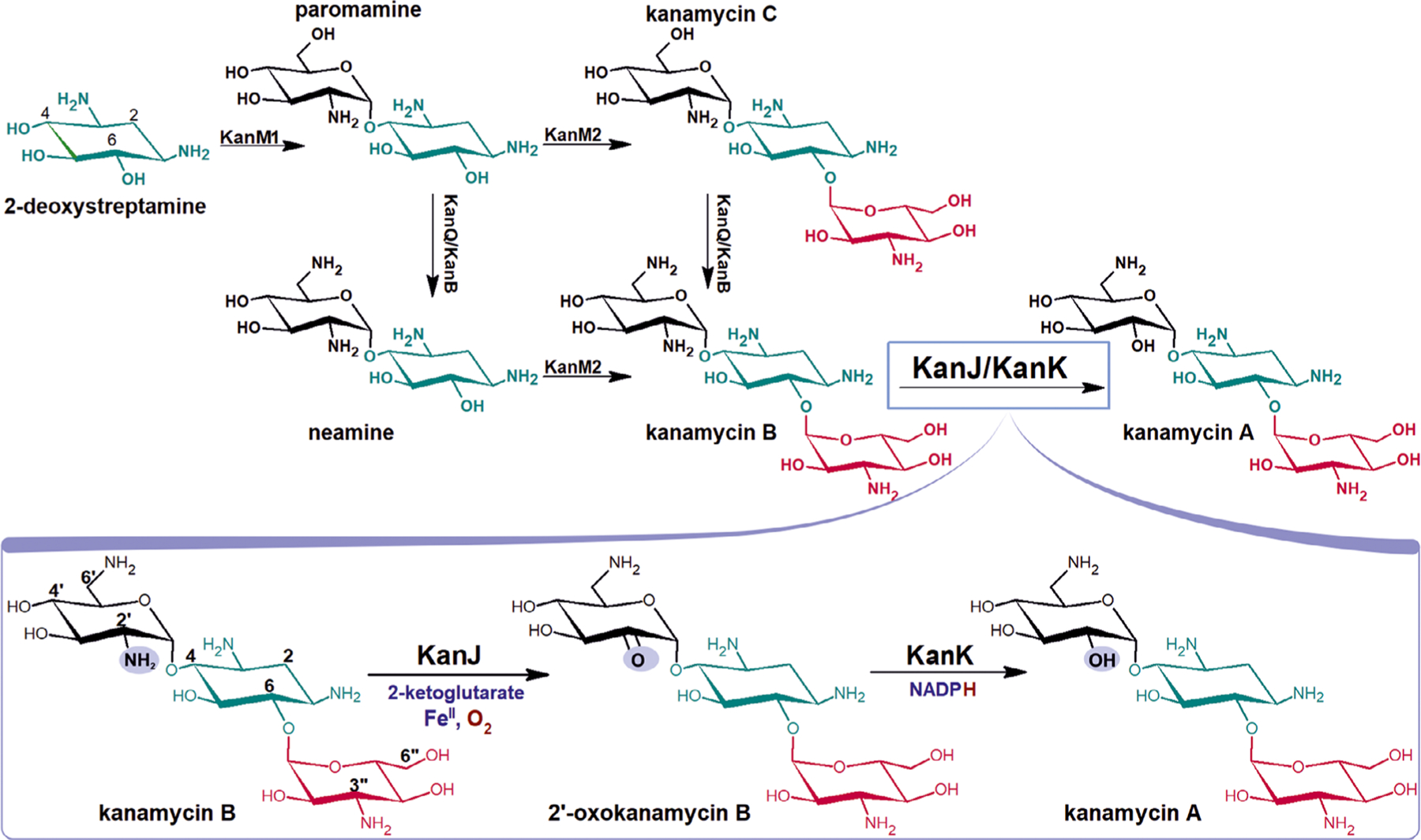

The first analysis of the gene cluster that is coding kanamycin biosynthesis proteins suggested a single pathway leading to kanamycin A through paromamine, kanamycin C, and kanamycin B, with the direct involvement of two glycosyltransferases: KanM1 and KanM2 and a pair of conjugate dehydrogenase and aminotransferase, that is, KanQ and KanB (Fig. 1) [15,16]. However, reconstruction of the entire biosynthetic pathway through the heterologous expression showed that the final compound may be produced in parallel pathways that start off with 2-hydroxyparomamine [17].

Fig. 1.

One of the proposed pathways of kanamycin A and B biosynthesis and details of the last stage of synthesis [16]. The 2-deoxystreptamine (2-DOS) is highlighted in green, kanosamine ring in red. Groups undergoing substitution are marked in blue. Kanamycin A biosynthesis is completed by the Fe(II)/αKG-dependent dioxygenase KanJ and the NADPH-dependent reductase KanK.

The last stage of the biosynthetic conversion of kanamycin B to kanamycin A is catalyzed by two enzymes: kanamycin B dioxygenase (KanJ) and NADPH-dependent 2’-oxo-kanamycin B reductase (KanK) [15]. In the first step (Fig. 1), oxidative deamination is carried out by KanJ yielding ammonia and 2’-oxo-kanamycin B, which is subsequently converted by KanK to the final product [18].

The KanJ protein is a nonheme iron, Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent dioxygenase (ODD) that belongs to a phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase (PhyH) family. Among many significant functions played by ODDs, most relevant here is their participation in antibiotics biosynthesis [19–21]. ODDs are responsible for catalyzing various chemical transformations including hydroxylation, ring formation, epoxidation, or desaturation [22–25] at any stage of the antibiotics’ biosynthesis, from generation of precursors, through modification of derivatives and intermediates, to formation of the target compound [24]. KanJ with its unique oxidative deamination reaction broadens this scope further.

To facilitate future work on new antibiotics, a detailed understanding of the biosynthetic pathways of aminoglycosides is needed, including information on atomic structure of the enzymes involved in the process. This knowledge might allow to modify the aminoglycoside biosynthesis pathways and to design new and hopefully more active drugs, akin to semisynthetic aminoglycosides. So far, several semisynthetic kanamycin and gentamicin derivatives have been successfully introduced into clinical use, for example, amikacin, arbekacin, dibekacin, and isepamicin [26].

Apart from previously published results of KanJ enzymatic activity tests that revealed the deamination activity of KanJ, which is novel for the ODD superfamily, there is no available information about the enzyme specificity and how it recognizes its substrates [18]. Here, we present the crystal structures of KanJ in several complexes (Table 1). Analysis of our KanJ 3D models, when combined with the results of binding assay, enzyme activity measurements, MD and DFT computations, allowed us to propose a mechanism of the KanJ enzymatic reaction and answer a question about relationship between KanJ’s substrate affinity as well as catalytic efficiency and the type and number of aminoglycoside rings in the substrate.

Table 1.

Crystallization, data collection, and refinement

| PDB ID | 6S0R | 6S0T | 6S0U | 6S0W | 6S0V | 6S0S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | KanJ-Ni | KanJ-Ni soaked with iodide (KanJ-IOD) | KanJ-Ni-αKG | KanJ-Ni-KAN | KanJ-Ni-NEA | KanJ-Ni-αKG-RIB |

| Crystallization | ||||||

| Ligand added | none | 100 mm potassium iodide soaking | 200 mm αKG cocrystallization | 100 mm kanamycin B soaking | 100 mm neamine cocrystallization | 200 mm αKG, 20 mm ribostamycin cocrystallization |

| Reservoir | 100 mm HEPES; 100 mm sodium acetate buffer; pH = 7.5, 500 mM Li2SO4, 28% (w/v) PEG4000 | 100 mm HEPES; 100 mm sodium acetate buffer; pH = 7.5, 500 mM Li2SO4, 28% (w/v) PEG4000 | 100 mm HEPES; 200 mm αKG; pH = 7.5, 25% (w/v) PEG4000 | 100 mm HEPES; 100 mm sodium acetate buffer; pH = 7.5, 500 mM Li2SO4, 28% (w/v) PEG4000 | 100 mm HEPES; 100 mm sodium acetate buffer; pH = 7.5, 500 mm Li2SO4, 28% (w/v) PEG4000 | 100 mm HEPES; 200 mm αKG; pH = 7.5, 25% (w/v) PEG4000 |

| Cryoprotection | parathone | drying over 1 M NaCl | drying over 1 M NaCl | drying over 1 M NaCl | Ethylene glycol 30% | Ethylene glycol 30% |

| Data processing and refinement | ||||||

| Resolution(Å) | (47.22–2.50) | (50.00–2.10) | (45.73–2.14) | (44.22–2.35) | (48.54–3.00) | (47.27–2.40) |

| Beamline | E 21-ID-D | 21-ID-G | 19-ID | E 19-BM | 21-ID-D | 19-ID |

| Detector | DECTRIS EIGER9M | MARMOSAIC 300 mm CCD | DECTRIS PILATUS3 6M | ADSC QUANTUM 210r | DECTRIS EIGER9M | DECTRIS PILATUS3 6M |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.48484 | 0.97856 | 0.97930 | 0.97915 | 0.97938 | 0.97930 |

| Space group | P 1 21 1 | P 1 21 1 | P 1 21 1 | P 1 21 1 | P 1 21 1 | P 1 21 1 |

| a, b, c [Å] | 50.37 | 50.61 | 49.83 | 50.44 | 50.47 | 50.08 |

| 184.21 | 186.47 | 183.69 | 186.06 | 185.25 | 184.58 | |

| 110.15 | 110.83 | 110.17 | 110.17 | 110.46 | 110.33 | |

| α, β, γ [°] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| 94.23 | 95.74 | 96.55 | 95.20 | 94.68 | 94.97 | |

| 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | |

| Completeness(%) | 87.5 | 96.4 | 92.2 | 95.1 | 90.7 | 91.1 |

| No. of reflections measured | 123338 | 118025 | 105045 | 75259 | 40424 | 67239 |

| Redundancy | 5.8 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 5.2 | 6.9 |

| <I>/<σ(I)> | 2.64 | 2.27 | 1.94 | 2.60 | 2.36 | 2.14 |

| CC ½ | 0.451 | 0.754 | 0.579 | 0.734 | 0.982 | 0.993 |

| Rmerge | 0.102 | 0.063 | 0.179 | 0.078 | 0.126 | 0.098 |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 37.7 | 24.7 | 26.1 | 31.5 | 55.1 | 36.1 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.170/0.208 13998 |

0.169/0.204 14953 |

0.196/0.244 14245 |

0.185/0.225 14359 |

0.200/0.228 13477 |

0.173/0.204 13802 |

| Total number of atoms | ||||||

| Average B, all atoms (Å2) | 47.0 | 35.0 | 33.0 | 63.0 | 60.0 | 50.0 |

| Validation of structure | ||||||

| Number of chains | 6 (A-F) | 6 (A-F) | 6 (A-F) | 6 (A-F) | 6 (A-F) | 6 (A-F) |

| Number of residues atoms [A-F chains] | 13124 (Avg = 2187) | 13197 (Avg = 2199) | 12961 (Avg = 2160) | 13046 (Avg = 2174) | 13104 (Avg = 2184) | 13082 (Avg = 2180) |

| Number of water [A-F chains] | 757 (Avg = 126) | 1628 (Avg = 271) | 1161 (Avg = 193) | 1007 (Avg = 167) | 145 (Avg = 24) | 462 (Avg = 462) |

| Ramachandran outliers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bond lengths RMSZ, #|Z| >5 | 0.66, 0/13556 | 0.57, 0/13718 | 0.73, 0/13424 | 0.63, 0/13447 | 0.63, 0/13509 | 0.66, 0/13511 |

| Bond angles RMSZ, #|Z| >5 | 0.80, 0/18644 | 0.78, 8/18858 | 0.87, 1/18459 | 0.78, 0/18499 | 0.77, 0/18583 | 0.82, 1/18584 |

| Ni2+B factors (Å2) [A-F chains] | 27, 22, 27, 31, 42, 31 | 21, 19, 22, 18, 30, 26 | 23, 19, 17, 17, 19, 17 | 44, 30, 40, 38, 51, 41 | 43, 43, 45, 52, 56, 50 | 36, 22, 26, 23, 45, 23 |

| Ni2+ RSCC [A-F chains] | 0.98, 1.00, 0.99, 0.98, 0.99, 1.00 | 0.99, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 0.99, 0.98 | 1.00, 0.99, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00,1.00 | 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.98, 0.99 | 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, 0.97, 0.99, 0.99 | 0.99,1.00, 0.99 1.00, 0.98, 1.00 |

| Median Ligand B factors (Å2) [A-F chains] | αKG 25, 18, 19, ,20, 17, 20 | Kanamycin B 60, 55, 65, 68, 61, 42 | Neamine 125, 121, 63, 55, 53, 30 | Ribostamycin 42, 37, 45, 38, 51, 32 | ||

| Ligand RSCC [A-F chains] | αKG 0.97, 0.98, 0,96, 0.97, 0.97, 0.98 | Kanamycin B 0.82, 0.80, 0.85, 0.88, 0.77,0.92 | Neamine 0.65, 0.85, 0.84, 0.89, 0.89, 0.84 | Ribostamycin 0.95, 0.97, 0.93, 0.97, 0.94, 0.98 | ||

Results

Protein expression, purification, and crystallization

Improvement in protein expression efficiency was obtained by extending the cells growth time before induction to 6 h and prolonging the induction period to 18 h. KanJ is a soluble protein obtained at a level of 30 mg of protein per 1L of culture. After the gel filtration chromatography step, the final yield of pure KanJ protein was 20 mg from 1L of culture.

In most of the tested crystallization conditions, KanJ crystallized in the form of fragile, thin, twinned rhombic plates with irregular edges. The first crystals appeared after 2 days, but due their poor quality they did not give diffraction. To slow down crystals growth, crystallization experiments were carried out with the addition of an oil layer, which reduced the speed of vapor diffusion. The initial crystallization hits were obtained at conditions containing 100 mM HEPES; 100 mM sodium acetate buffer; pH = 7.5, 200 mM Li2SO4, 20% (w/v) PEG4000. These conditions were later optimized by varying concentrations of Li2SO4 and PEG4000 and by adding 200 μL silica oil to the reservoir. From these conditions grew single, well-formed crystals with regular sharp ends and sizes of 0.1–0.5 mm. Final crystallization conditions are presented in Table 1. Diffraction quality crystals grew within one week, and some of them were soaked with potassium iodide to further improve their quality. Crystals soaked or cocrystallized with antibiotics appeared after 10 days but, despite the optimization of the ligands concentration, their quality was worse than native crystals and, after a few days, some of them dissolved. The best results were obtained with soaking 100 mM kanamycin B and cocrystallization with 20 mM ribostamycin and 100 mM neamine.

Structure determination

The initial structure was determined from KanJ-Ni (6S0R) dataset by Ni single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (Ni-SAD). There were two dominant lattices present, but only the weaker one gave a significant anomalous signal, as it could be consistently processed through the whole oscillation range. Two lattices present in the 6S0S dataset were integrated separately and scaled together using 1–130° from the first (stronger) lattice and 1–220° from the second lattice. To integrate two lattices in HKL-3000 [27], the diffraction images were integrated in two passes. During the first pass, the data were integrated using automatically determined crystal orientation (using automated peak search implemented in xdisp). To determine the orientation of the second lattice, after automated peak search, the peaks overlapping with the first integrated lattice were automatically removed (as implemented in xdisp) and the remaining peaks were autoindexed. If that procedure resulted with the same orientation as the first lattice, the peaks corresponding to the second lattice were selected manually. For this dataset, the radiation dose model based on the scaling B factors [28] was used instead of the standard linear one. Remaining datasets were processed using single, strongest lattice if multiple lattices were present. Data reduction and scaling for all structures were carried out with HKL-3000. All datasets were processed using automated corrections and absorption correction. Phasing, model building, and refinement were done using HKL-3000 integrated with shelxd, shelxe [29], mlphare, buccaneer [30], molrep [31], fitmunk [32], refmac [33], and other auxiliary programs from CCP4 [34]. The initial 6S0R model was used as a model for a molecular replacement (MR) to determine the 6S0T structure, and the refined 6S0T model was used as a MR model to determine the remaining structures. The structures were refined as described in a recent review [35] and validated using molprobity [36] and wwpdb validation service [37].

Overall structure

KanJ crystallized in the monoclinic space group P1211 with six protein monomers per asymmetric unit. The structures of KanJ (2.10–3.0 Å resolution) have visible electron density for main chain atoms and most side chains (Fig. 2A). The crystallographic data are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Overall structure of KanJ. (A) Quaternary protein structure—six protein monomers in asymmetric unit in the monoclinic space group P21. (B) Monomer with a typical double-stranded β-helix (DSBH) fold composed of eight β-strands. β3, β5, β8, and β10 create a part of the major β-sheet, whereas β4, β6, β7, and β9 form the minor β-sheet. The major β-sheet is extended by five additional β-strands, two at the N-end, and three at the C-end. (C) Nickel coordination in the active site by the conserved HXD···H binding motif created by His132, Asp134, and His219. Coordination is completed by αKG and a water molecule. Fo−Fc omit map for αKG is contoured at 3.0r (gray mesh). pymol was used to generate the structure.

Despite relatively low amino acid sequence identity (19–20%), results of structural comparison indicate that there is considerable structural similarity between KanJ and enzymes from the PhyH family, such as fumitremorgin B endoperoxidase (FtmfOx1, PDB ID: 4Y5T) [38], quinolone dioxygenase (AsqJ, PDB ID: 5DAP) [39], and Phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase (PhyH, PDB ID: 2OPW) (Fig. S1). Similarity is most evident for the double-stranded β-helix (DSBH) and the N-terminal helical regions (Fig. S1). The DSBH, aka ‘jelly roll’ fold, is common among ODDs [40]. The DSBH is located between three mainly α-helical regions that beside stabilizing the ‘jelly roll’ core, limit the mobility of the loops that form the entrance to the binding pocket. Flexible loops, which are connectors between DSBH elements, participate in forming the enzyme active site and provide hydrophilic and negatively charged residues directly engaged in antibiotic binding. KanJ and PhyH have similarly large and wide open binding pockets [39]. KanJ has a binding pocket sufficiently spacious to accommodate bulky aminoglycoside antibiotics, and details of substrate recognition are described in the following section.

Active site

A catalytically inactive enzyme containing Ni(II) ions instead of Fe(II) was used for crystallization studies to limit oxidative damage of the protein. As it has been shown previously, iron to nickel substitution does not affect coordination geometry in the range larger than typical uncertainties of the crystallographic model of a medium resolution structure [41]. Due to the similarity of these two transition metal ions, the nickel-coordinating ligands are the same as for iron; this observation has been confirmed in earlier studies on ODD enzymes [42–44].

Discussed in this and subsequent section structural models and electron density maps can be inspected interactively using Molstack [45] at https://molstack.bioreproducibility.org/project/view/gxkDNGZ6e5yNn05WM4cg/ and https://molstack.bioreproducibility.org/project/view/0jueO1qKmbB1RM55jAV1/. In analogy to other ODDs, nickel ion is located between three β-strands that create the DSBH core (Fig. 2B,C). Proximal His132 and Asp134 metal ligands originate from the short beta-strand β5 and the (134–147) loop, whereas the distal His219 comes from β11, and together, they form the highly conserved HXD···H metal binding motif, which provides two His and one Asp ligands occupying a single face of coordination octahedron. Average distances between nickel ion and histidine NE2 and aspartate OD1 are 2.12(±0.02) and 2.03(±0.02) Å, respectively. In the structures containing αKG (PDB ID: 6S0U, 6S0S), nickel coordination shell is completed by αKG (with a ligand occupancy of 1.0 in both structures) and one water molecule, which is clearly visible in the electron density map at the distance of 2.02 Å from Ni(II). αKG binds to nickel ion in a bidentate manner; oxygen of the C1 carboxyl group of αKG is ligated trans to His219, and the oxo group trans to Asp134. In all structures without αKG, an approximately octahedral coordination shell of nickel ion is completed by three water molecules. The relative arrangement of the metal cofactor and the antibiotic suggests that the oxo ligand of the ferryl species most probably binds at the coordination site opposite to His219, which becomes available upon decarboxylation of αKG and is also closest to the C2’ carbon of the antibiotic.

Several hydrogen and electrostatic interactions participate in αKG binding. Gln129, Thr165, and Arg230 form hydrogen bonds with the C5 carboxylic group of αKG. Arg230 comes from the beginning of the last β-strand (β10) of the DSBH motif, whereas Gln129 and Thr165 come from loops (123–147) and (155–165), respectively. Glutamine and threonine residues are often found in ODDs as functional elements that recognize the C-5 group of αKG [46].

The comparison of structures with αKG (PDB ID: 6S0U) and with SO42− (PDB ID: 6S0R) shows that for Gln129, Thr165, and Arg230, which form H-bonds with αKG, there are no conformational changes between αKG and SO42−-bound complexes; the hydrogen bond between the -NH2 group of arginine and αKG is only 0.2 Å shorter compared to Arg230–SO42−. In contrast, Asn120, which makes van der Waals contacts with αKG, has slightly different conformations in the KanJ-Ni (PDB ID: 6S0R) and KanJ-Ni-αKG (PDB ID: 6S0U) structures.

Binding of aminoglycosides to the KanJ protein

To get further insight into the structural basis of substrate recognition by KanJ, three antibiotics that differ in number of rings and 2-DOS substitution pattern were used for crystallization experiments: kanamycin B—natural substrate of KanJ, neamine, which is a two-ring aminoglycoside lacking the C-ring and ribostamycin, in which the 2-DOS ring is substituted at the position 5 by ribose. Cocrystallization trials resulted in one ternary complex of KanJ-Ni with αKG and ribostamycin–KanJ-Ni-αKG-RIB (PDB ID: 6S0S) and two binary complexes: with kanamycin B–KanJ-Ni-KAN (PDB ID: 6S0W) and partially bound neamine–KanJ-Ni-NEA (PDB ID: 6S0V). Instead of αKG, structures with kanamycin and neamine contain sulfate ions bound in its place. Although in structures with antibiotics the electron density maps differ in quality between individual chains, the maps are well defined for the ligands (as can be seen at the Molstack project mentioned above). In all three structures, antibiotics are bound in the active site in a similar manner (Fig. 3). Among the three rings of antibiotics, the ring A is deepest buried inside the binding pocket and forms most of the antibiotics’ interactions with the surrounding amino acid residues. The ring A also undergoes the oxidative transformation catalyzed by KanJ.

Fig. 3.

Surface representation of KanJ—kanamycin B complex with marked residues that stabilize the antibiotic in the binding pocket. Comparison to binding of neamine (a) and ribostamycin (b) shows that rings A and B of different antibiotics bind in the same way. Carbon atoms of neamine, ribostamycin and kanamycin B are colored yellow, blue, and green, respectively. Fo-Fc omit maps of antibiotics in the active site are contoured at 3.0σ (gray mesh) A—kanamycin, B—ribostamycin, C—neamine. CCP4 was used to create Fo–Fc omit maps and PyMOL to generate structures.

The surface of the broad entrance to the substrate binding cavity is made up by hydrophilic groups provided by four short flexible loops (67–76), (239–246), (258–264), and (270–276). The first of them forms the innermost part of the active site surface interacting with the ring A of antibiotics, whereas the next three, connected by two beta strands: β10 and β11, create the outer walls of the binding site. The antibiotic binding site is coformed by residues from the DSBH core, mainly from strands: β4, β5 and β7. For structures with kanamycin and neamine, a change in the conformation of the C terminus fragment (270–285) can be observed between individual protein monomers. Monomers labeled as chains D and F feature the closed (II) conformation, whereas others are best described as having the open (I) conformations. The residues that move the most during this conformational change are those from Thr277 to the end of the protein chain (Fig. 4). Concerning substrate recognition, an interaction between the antibiotic and Phe282 from this C-terminal fragment seems important, as in the closed conformation Phe282 induces the rotation of Gln80, which is directly involved in the antibiotic binding. It has been observed that when the C terminus has the ability to bind to kanamycin, Gln80 adopts a more favorable conformation by changing the dihedral angle around the Cβ-Cγ bond by about 30 degrees, which promotes stronger interactions with the ligand. In all aminoglycoside-bound structures, rings A and B of all antibiotics occupy the same locus of the active site (Fig. 3). For all of them, the majority of protein–antibiotic interactions occur for the ring A, which is located closest to the metal ion. C3’- and C4’-bound hydroxyl groups make H-bonds with side chains of Gln80 and Asn120. In all structures, the positively charged C6’-NH3+ group forms hydrogen bonds with Asp134 and for kanamycin and neamine additionally with Cys150 and through water bridges with the Asp152 side chain and the Met235 main chain. For ribostamycin, interactions with Asp134 and Cys150 are weaker, as judged by elongated distances between the antibiotic and protein residues; additionally, the amino group of C6’ forms H-bonds with Ser118. Ring B is mainly stabilized by hydrogen bonds with Glu135, a hydrogen bond with a preserved water that also makes H-bonds with Thr236 and Tyr238 and hydrophobically stabilized by Phe282, which also forms a H-bond between the main chain oxygen atom and the C2’-bound amino group. The third ring (C) of kanamycin extends into the solvent and makes a H-bond with Gln182 main chain and hydrophobic interactions with Arg183 and Val284. The 2-DOS ring of kanamycin B (ring B) is substituted at the C4 and C6 positions, which makes the rings A and C are approximately symmetrically arranged with respect to the central ring B, and the whole antibiotic molecule has an extended form. Ribostamycin, due to the substitutions at positions C4 and C5, has a more crescent-like shape. As a result, the ring C of ribostamycin is bound deeper in the active site than in the KanJ–kanamycin complex and it is also closer to the metal cofactor, which may have consequences for substrate binding and turnover. The ring C of ribostamycin makes hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Arg183 and also two metal ligands, that is, αKG and His132, and the latter interaction is observed in most of the better ordered monomers. Interactions with the first shell ligands may interfere with proper coordination of the metal by αKG as well as the proper arrangement of the reactive group of the substrate with respect to the iron cofactor.

Fig. 4.

KanJ binding site with bound kanamycin B. (A) Conformational changes of the C terminus fragment (270–285) from an open (state I) to a closed (state II) during kanamycin binding. (B) Residues involved in H-bonding to the ligand are labeled. (C) Comparison between the open and closed states: upon antibiotic binding the side chains of Gln80, Asn120 and Glu182 are changing their conformations. Reducing the distance between the loop and the active center induces the rotation of Gln80 and Asn120, which improves the stability of the antibiotic. (D) Binding of kanamycin B to the KanJ protein measured by ITC. (Top panel) Raw data obtained for titration of kanamycin B (1 mm) into the KanJ protein (0.1 mm) in a buffer composed of 10 mm HEPES 7.5 and 50 mm NaCl at 25 °C. (Bottom panel) Integrated heat profile of ITC data showing the binding enthalpies corrected for heat of ligand injection. A one set of sites model was fit into the data using Origin Software. The thermodynamic parameters of the model used to interpret the data are presented. PyMOL was used to generate the structures.

A preserved water molecule (e.g., water 1700 in chain D) that is present in most KanJ-Ni-KAN chains at a distance ~ 2.70 Å from the C2’-NH2 is replaced by the ribostamycin C4’’-CH2-OH side chain of the ring C. The absence of the preserved water in the KanJ-Ni-αKG-RIB and the steric hindrance associated with the close contact between the ribose ring and the iron cofactor may significantly affect the course and nature of ribostamycin’s reactivity. Indeed, this conjecture is in line with a slower conversion rate for ribostamycin as compared to kanamycin B, as discussed in later subsections.

Further, to assess the effect of the different aminoglycosides’ structure on their interaction with the KanJ protein, ITC binding tests with kanamycin B, neamine, and ribostamycin were performed. At pH 7.5, KanJ Kd for kanamycin B is 1.54 μm (Fig. 4D), whereas the binding stoichiometry N = 0.884, which goes well with the assigned occupancy of the antibiotic in the binding site. Unfortunately, values of thermodynamic constants and stoichiometry obtained for the same antibiotic in different conditions (pH, type of buffer, ionic strength) indicate that several parallel processes take place during binding of kanamycin, and they are presumably associated with different protonation of amino groups of the antibiotic and protein residues rendering the analysis difficult. Unfortunately, the same problems were encountered for neamine and ribostamycin binding; hence, no thermodynamic values could be obtained from ITC measurements for these antibiotics.

Enzymatic activity

The identity of metal bound to KanJ was verified for purified protein samples by ICP-OES; the occupation of nickel and iron was 66.7%±5.0% and 0.4%±0.1% with respect to the protein concentration. Due to low iron content in the purified protein sample, the reaction mixture used for KanJ activity test contained iron ions needed to reconstitute the native holo form of the enzyme, that is, KanJ-Fe(II) [18]. The protein occurred to be highly active in acidic pH. For the reaction conducted at pH = 6.3, complete conversion of kanamycin B (80 enzyme turnovers) to 2’-oxo-kanamycin B was obtained 15 min after starting the reaction (Table 2), whereas in more basic environments (pH = 7.0 and 7.5) the reaction proceeded more slowly (24% and 12% of 2’-oxo-kanamycin B, 60 min after starting the reaction, respectively). In the case of neamine, the reactivity was similar to that observed for the native substrate. In contrast, the reactivity tests for ribostamycin showed that the antibiotic is slowly converted, yet the largest amount of the reaction product—oxoribostamycin was detected at neutral pH, in comparison with more acidic and basic pH. The results obtained in experiments with reaction time of 60 min are consistent with those for 15 min, but demonstrate the differences in reactivity at different pH values even more clearly. High-pressure liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry allowed us to analyze the composition of the reaction mixture (Figs S2–S19 and Tables S1–S6). Firstly, in the scan mode we have observed that for all of the substrates [M + H] adducts were converted to corresponding product [M + H] adducts, which were lower in mass by m/z = 1. Moreover the isotope patterns for both products and substrates matched the theoretical patterns for compounds containing C, H, N, O atoms. Further, for both products and substrates, comparison of the theoretically predicted composition of product ions obtained from [M + H] adduct fragmentation with those obtained from HPLC-MS experiments enabled us to confirm generation of oxo-products through assignment of the observed ions.

Table 2.

The substrates (kanamycin B, neamine, and ribostamycin) loss over 15 and 60 min. Errors represent standard deviation calculated for three (n = 3) repetitions of each measurement

| Substrate loss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH = 6.3 | pH = 7.0 | pH = 7.5 | ||

| Kanamycin B | 15 min | 100% | 42% ± 3% | 17% ± 5% |

| 60 min | 100% | 52% ± 9% | 31% ± 7% | |

| Neamine | 15 min | 82% ± 4% | 67% ± 9% | 44% ± 13% |

| 60 min | ± 10% | 68% ± 3% | 39% ± 16% | |

| Ribostamycin | 15 min | 17% ± 10% | 44% ± 13% | 12% ± 13% |

| 60 min | 27% ± 6% | 59% ± 11% | 21% ± 14% |

Computational analysis of reaction mechanism

In our study, we tested two possible mechanistic pathways for oxidative deamination elicited by reactive ferryl species—the first involving an imine intermediate, and the second proceeding through a hemiaminal intermediate. With this aim in mind, first, three models were used for MD simulations and their purpose was to obtain a reliable structure for the complex between the substrate and an activated form of the enzyme, that is, with the ferryl species bound in the active site (in two possible configurations). MD simulation results obtained for the model with the rotated oxo ligand showed that in this arrangement kanamycin B is optimally exposed toward the ferryl species. Hence, this macromolecular model was used to create a smaller active site model that was used for DFT computations to test possible reaction mechanisms. As pKa of the amine group bound at the C2’ position (the reaction site of the antibiotic) is 8.6, two alternative models of the active center, with different protonation of this amine group, were used and compared.

To equilibrate and solvate the structures, we first conducted MD simulations for three KanJ complexes with: (A) kanamycin B, αKG, and a water molecule, the latter two as Fe(II) ligands, or with succinate and an oxo ligand coordinated to Fe(IV) in two arrangements: (B) oxo ligand trans to His132 (in a position formerly taken by water), (C) oxo ligand trans to His219 (a coordination site closest to the substrate).

The MD production runs were carried out until RMSD profiles reached stable values (for systems A, B, and C 1.4, 1.7, and 1.5 Å, respectively). The distance between the oxo ligand of the ferryl species and the H(-C2’) atom of the substrate, measured for the three simulated complexes, shows that the configuration with rotated oxoferryl (C) allows for direct H atom transfer. The rO…H distance between the abstracted H atom and the oxo ligand is on average 2.2 Å over 40 ns for C, whereas in other cases the distance between this hydrogen and the water molecule coordinated to Fe(II) (A), or the oxo ligand (B), is larger (on average 3.9 and 5.0 Å, respectively) and fluctuates widely (Fig. 5). Moreover, the computed barrier for rotation of the oxoferryl group, from the position trans to His132 (51’) to the site trans to His219 (51), is only 10.5 kcal·mol−1 (5TSr) and this elementary step leads to an energy drop by 1.8 kcal·mol−1. Importantly, the more stable configuration corresponds to the complex C with the oxo ligand pointing toward kanamycin B.

Fig. 5.

Respective crucial O-H distance over MD production runs between abstracted hydrogen of kanamycin B and: (A) oxygen of water (System A); (B) oxoferryl species; (C) oxoferryl species rotated toward substrate; lower panels present close up views of active center for corresponding MD runs with monitored distances marked in black; (D) Cluster model used for QM calculation for system C includes groups representing the first and the second shell residues. Residues were cut at Cα-Cβ bonds (Arg at Cγ-Cδ). Frozen hydrogen atoms, replacing Cα(Cγ), are shown in a ball representation. The initial distance [Å] between an oxygen atom of the oxoferryl species and the H atom to be abstracted is marked. VMD was used to render the models and Gnuplot to prepare time-series.

For the complex C, the most populated cluster of MD snapshots accounts for 43.7% of all analyzed snapshots. Oxidative decarboxylation of αKG, which takes place in the first half of the catalytic cycle and was not studied here, yields reactive ferryl species (51/51B; Fig. 6). For 51, spin populations of Fe and O atoms are 3.21 and 0.57, respectively, and the Fe = O bond has the characteristic length of 1.661 Å. Considering the model with the protonated amino group bound at the C2’ position (1), the reaction begins with H atom abstraction yielding Fe(III)-OH and a C2’-centered radical; the computed barrier for this step is 12.6 kcal mol−1 (Fig. 6).5TS1 For 5TS1, the distances for C2’-H and H-O bonds are 1.300 and 1.239 Å, respectively. The spin population on iron changes from 3.21 to 4.16, which indicates high spin Fe(III) is formed, while at the C2’ atom a radical center develops with an unpaired β spin population equal to 0.44. For species 1, the triplet spin state was calculated to lie 10.4 kcal·mol−1 higher in energy than the quintet and the energy obtained for the triplet transition state 3TS1 is two times higher than for its quintet counterpart, that is, 23.7 kcal·mol−1, and therefore, the triplet spin state was not taken into further consideration.

Fig. 6.

Computed reaction energy profiles for two mechanisms starting off with: (A) protonated amine (C2’-NH3+) and proceeding through the hemiaminal or imine intermediate; (B) deprotonated amine (C2’-NH2) and involving the imine intermediate. Relative energies of reactants and barriers are corrected for zero point energy and given in kcal/mol. Depicted pathways refer to the quintet spin state. Lower panels present possible pathways of C2’-NH2 group dissociation in water for: (C) hemiaminal species, (D) protonated imine, (E) imine. All reaction schemes present structures corresponding to local minima on potential energy surfaces.

The product of the C-H bond cleavage is 52, which features high spin Fe(III) (spin population of 4.25 on Fe), coordinated by the OH group (spin population of 0.24 on the O atom), and the C2’-centered radical with β spin population of 0.98. For the subsequent reaction step, there are two scenarios. First, in the rebound process the OH group bound to Fe(III) and the C2’-centered radical recombine; this involves a barrier of 14.4 kcal·mol−1 (5TS2) and leads to a very stable hemiaminal intermediate 3 (−43.0 kcal·mol−1). 5TS2 is characterized by an Fe-O bond elongated to 1.924 Å, whereas the radical carbon–OH distance is 2.415 Å. The spin populations, which are 4.21 for Fe and 0.22 for the O atom, indicate Fe at the III oxidation state, while at C2’ the β spin population is still high, that is, 0.88. In the resulting intermediate with the hemiaminal species (53), only the Fe ion has unpaired electrons and its spin population of 3.81 indicates that Fe(II) was recovered. The second possible pathway leads through proton transfer from the C2’-bound NH3+ group to Fe(III)-OH (TS2’) followed by electron transfer, from the C2’-centered radical to the metal cofactor, yielding imine group at C2’ and recovered Fe(II). Such a process is strongly exothermic and involves a barrier of only 1.2 kcal·mol−1. Thus formed imine needs to be hydrolyzed to the final keto product. However, as computed for the KanJ active site model, direct addition of water to imine requires overcoming a barrier of 35.5 kcal·mol−1 (TS4’) leading to hemiaminal (3). Subsequent deamination is also energetically demanding, and the barrier (TS3) is 31.1 kcal·mol−1 and involves a proton transfer from the C2’-bound OH group to the dissociating amino group; the process is mediated by Asn73 and yields carbonyl group at C2’ and free NH4+ (4). In light of high barriers computed for the imine hydrolysis within the enzyme active site, it is worth considering if this process could be catalyzed by water molecules and proceed in solution. Indeed, simple models for water catalyzed hydrolysis of imine gave much lower barriers, the lowest found in this study for NH4+ dissociation is 19.1 kcal·mol−1 (Fig. 6C, TS5). Addition of a water molecule to protonated imine is also easier in solution (Fig. 6D, TS5’) with a computed barrier of 24 kcal·mol−1.

Since the pKa of the C2’-bound amino group is close to neutral (pKa = 8.6) [47], besides the model with this amino group protonated, which was discussed above, a model with charge-neutral amino group was considered (1B). Interestingly, in this case the first step, which is formally a H atom abstraction, is combined with two electron reduction of Fe(IV)=O and leads directly to a complex with imine and Fe(II)-OH2. The spin population on Fe changes from the initial 3.16 to 2.97 in TS1B and then to the final value of 3.82 for the intermediate with an imine species (2B). The barrier computed for such a process is 12.3 kcal·mol−1 (TS1B), which is comparable to the analogous barrier obtained for the protonated (C2’-NH3+) form of the reactant (12.6 kcal·mol−1; TS1). For TS1B, interatomic distances for bonds being broken and formed are 1.194 Å (C-H) and 1.535 Å(O-H), respectively, which means it is an early TS. Subsequent reaction stage, that is, imine hydrolysis may take place in the water environment (Fig. 6E).

Discussion

Previous research on kanamycin biosynthesis revealed that the process can proceed in two different ways. In the first, the key enzyme is glycotransferase KanF (also known as KanM1) that carries glucose and N-acetyl glucose to 2-DOS [48]. In the second, two enzymes, the Fe(II)/αKG-dependent dioxygenase KanJ and the NADH-dependent reductase KanK, finalize the reaction. Until now, none of the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of kanamycin has been structurally characterized, which severely limits atomic-level information about the mechanisms of individual stages of this vital process. In this work, we focused on structural characterization of KanJ, probed its substrate range, and studied plausible reaction mechanisms of the unique oxidative deamination reaction. We obtained diffracting crystals and solved a model that offers valuable information about the ligand binding site and substrate specificity of the protein. For a better understanding of substrate recognition, we crystallized KanJ complexes with Ni(II) and ligands: αKG, kanamycin, neamine, and ribostamycin. In the last case, we obtained crystals for the KanJ-Ni(II)-αKG–ribostamycin complex, which is an analogue of the structure formed during the catalytic cycle just before O2 binding and activation, with the caveat that ribostamycin as a slow substrate might bind somewhat differently that KAN. So far, the KanJ activity has been studied on its main substrate—kanamycin B. The crystal structures and results of activity tests reported herein show the substrate specificity of the enzyme is broader; it encompasses also neamine and ribostamycin. Results of additional ITC measurements showed that all tested antibiotics bind to KanJ; however, only for kanamycin the obtained data could be interpreted with a simple binding model. From ITC results, it follows that the optimal conditions for binding of antibiotics require neutral pH and low ionic strength. For kanamycin and neamine, the highest enzymatic activity is observed at pH = 6.3; however, for ribostamycin, which is processed by KanJ very slowly, an optimum reaction pH seems to be at neutral pH. This variation probably results from slight differences in pKa [47,49,50] values of amino groups of the tested aminoglycosides. The obtained crystallographic and biochemical data suggest that a necessary condition for the substrate recognition is the presence of the ring A (6-amino-6-deoxy-α-D-glucopyranosyl), which is recognized in the active site mainly by Asn73, Gln80, Asn120, Asn134, and Cys150. Notably, antibiotic binding triggers a conformational change of the C-terminal fragment of the protein, which swings toward the substrate and stabilizes its binding in the active site. Results obtained for ribostamycin show that for bigger aminoglycosides the 2-DOS ring should optimally be substituted at positions 2 and 6, because substitution at positions 2 and 5 creates a steric hindrance. Accordingly, the largest reactivity was observed for kanamycin, which was followed by neamine. Ribostamycin was the least reactive substrate.

The structural data have also allowed us to study the mechanism of the unique oxidative deamination reaction catalyzed by KanJ. Using a computational model derived from the obtained crystal structures, we tested plausible mechanisms of the decisive reaction steps elicited by the reactive ferryl species. Assuming the C2’-bound amino group of kanamycin B is positively charged (pKa = 7.23 for neamine [51]), the barrier for OH rebound is much higher than the barrier for deprotonation of amine group and subsequent electron transfer, which leads to protonated imine intermediate product. For the form of the substrate with the key amino group deprotonated (C2’-NH2), the first step, that is, H atom abstraction, triggers immediate formation of an imine intermediate product. The subsequent reaction steps, that is, water elimination from hemiaminal or water addition to imine, are predicted to proceed within the KanJ active site with barriers exceeding 30 kcal·mol−1, which casts them unlikely. However, much lower barriers for these steps were obtained for models of the reactions taking place in solution, which suggests that this stage of the reaction may proceed outside of the KanJ active center.

In a broader perspective, the presented mechanism is the detaching of an amine group from carbon that was previously oxidized by introduction of a hydroxyl group. Similar reaction is observed in other Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes such as the Jumonji C histone demethylases [52] or AlkB protein—an alkyl DNA adducts repair enzyme [53]. In the case of histone demethylases, a mechanism that involves imine formation is considered for enzymes that belong to a class of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent amine oxidase (LSD1) [54].

The results presented here contribute to atomic-level understanding of the kanamycin biosynthesis, and we believe this work will serve for new drugs development via future modifications of kanamycin biosynthesis pathway or designing new catalysts for antibiotics synthesis.

Materials and Methods

Gene synthesis, cloning, protein expression, and purification

The gene encoding KanJ from Streptomyces kanamyceticus (UniProt ID: Q6L732) was synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, US) in a pET28b vector and optimized for expression in E. coli. The gene was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5’-CATATG ACGTCT CAAATG GAAAAC CTGTAC TTCCAA TCCAAT GCG-3’ (forward) and 5’-TAATGA TAACAT TGGAAG TGGATA AGGGAT GAGACG GGATCC-3’ (reverse) and cloned into the pMCSG7 vector. The protein expression was done in E. coli BL21(DE3)/MAGIC strain. Cells were cultured in 50 mL LB broth containing 100 μg·mL−1 ampicillin and 50 μg·mL−1 kanamycin at 37°C overnight in shaking incubator. 10 mL of inoculum was transferred into 1L of TB media containing the same antibiotics, and culture was shaken at 37°C, 220 rpm for 6 hours to reach an OD600 of 1.0. Overexpression was carried out at 16 °C in a presence of 0.3 mm IPTG for 18 h.

Cell pellet was harvested by centrifugation at 4000 rpm (J-26XP, Beckman, Brea, CA, USA) for 45 min at 4°C and re-suspended in a cold lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, 200 mm NaCl, 2 mm imidazole; pH = 7.8) with protease inhibitor (Complete Protease Inhibitor Tablets, Roche, Penzberg, Upper Bavaria, Germany) to a final volume of 50 mL. Lysozyme (0.1 mg·mL−1, Sigma-Aldrich) and DNAse I (0.05 mg·mL−1, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) were added and the mixture was left on ice for 30 min before passing through a glass homogenizer. Partially disrupted cells were passed four times through a cell disruptor and then sonicated on ice for 4 min (5s on and 3s off). The lysate was centrifuged at 40000 rpm (45Ti, Beckman) for 30 min at 4°C.

Ni-affinity chromatography

Ni(II)-nitrilotriacetic agarose ‘Ni-NTA’ (5mL, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was packed into a gravity-flow column equilibrated with the lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, 200 mm NaCl, 2 mm imidazole; pH = 7.8) and washed with wash buffer (50 mm Tris, 500 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole; pH = 8.0), and protein was eluted with elution buffer (50 mm Tris, 200 mm NaCl, 250 mm imidazole; pH = 8.0). The presence of protein was confirmed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Bradford) (1:10).

To remove 6xHis tag, the protein was concentrated to 5 mg·mL−1 (20 mL) using Amicon ultra 30 kDa MWCO centrifugal filter (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The absorption at 280 nm was measured using NanoDrop 2000 UV-Vis spectrophotometers (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the protein concentration was calculated using an extinction coefficient obtained from PROTPARAM tool [55] (ExPASy Bioinformatics Resource Portal). 2 mL of 1 mg·mL−1 of TEV protease was added to the protein, and proteolytic digestion was done during dialysis in the buffer composed of 50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl; pH = 7.8 for 18 h in SnakeSkin Pleated Dialysis Tubing 10K MWCO (Thermo Scientific). The KanJ/TEV mixture was loaded onto the gravity-flow Ni-NTA (2 mL) column pre-equilibrated with a dialysis buffer. The tag-free KanJ protein was collected as the flow-through, concentrated to 10 mg·mL−1 and stored in 50% (v/v) glycerol at − 80 °C.

Gel filtration chromatography

The tag-free KanJ protein was loaded onto Superdex 200 column (1.6×60 cm) attached to the AKTA Purifier system (GE Healthcare, Boston, MA, USA). The column was equilibrated with a buffer containing 50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl; pH = 7.8. The chromatography run was performed at a flow rate of 1 mL·min—1. The collection of 2 mL fractions was monitored by absorbance at 280 nm. Purified KanJ was concentrated using an Amicon centrifugal filter (cut-off 10 kDa) to 20 mg·mL−1 as measured by absorbance at 280 nm and stored at − 80 °C.

Crystallization

Crystallization experiments were carried out by the hanging or sitting drop method manually or by TTP Labtech’s mosquito® robot (Melbourn, England), respectively. Initial crystallization conditions of the KanJ (15 mg·mL−1; 50 mm Bis-Tris, 150 mm NaCl, pH = 7.5) were screened using Jena Bioscience Crystal Screens (I-VIII) (Jena, Germany) by hanging-drop. Droplets (2 μL of protein plus 2 μL of precipitant) were set up above reservoir with 450 μL crystallization screening kit and dispensed into 24-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmu€nster, Austria), pH = 7.8. Plates were stored at 4°C.

Diffraction quality crystals grow within one week using the reservoir solution containing 100 mm HEPES; 100 mm sodium acetate buffer; pH = 7.5, 500 mm Li2SO4, 28% (w/ v) PEG4000 with addition of silica oil into reservoir.

Crystals from the same conditions also were soaked with 50 mm potassium iodide for 72 hours, then either dehydrated above 1 M NaCl (8 min) or combined with ethylene glycol (30%) for cryoprotection and finally flashed cooled with liquid nitrogen. Crystals of KanJ/kanamycin B complex were obtained by soaking the KanJ crystals with 100 mm kanamycin B solution in 50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl buffer, pH = 7.5.

Crystals containing αKG were obtained by dialysis of the protein to a solution of 200 mm αKG, pH = 7.5. Droplets (2 μL of protein plus 2 μL of precipitant) were set up above reservoir that contained 450 μL 200 mm αKG, 25% PEG4000, pH = 7.5, in 100 mm HEPES and distributed into 15-well plates (EasyXtal, Qiagen).

To obtain a two-component complex containing αKG and aminoglycoside, drops of protein in 200 mm αKG (300 nL of protein plus 300 nL precipitant) were set up above 34 μL 200 mm αKG, 25% PEG4000, 20–100 mm antibiotics, pH = 7.5, using TTP Labtech’s mosquito® robot and 96-well plates (Swissci 96-well 3-drop ULTRA low profile, Thermo Scientific).

X-ray diffraction data collection, data processing, and structure determination

Datasets of KanJ with sulfates were used for single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) experiments to obtain initial phases for model building.

Diffraction data were collected at temperature of 100 K at beamlines 19-BM and 19-ID of the Structural Biology Center and beamline 21-ID-D of the LS-CAT at the Advanced Photon Source (APS). Data reduction and scaling for all structures were carried out with HKL-3000 [27,56]. All datasets were processed using SCALEPACK, automated corrections, and absorption correction.

The initial structure was determined from the KanJ-Ni dataset by Ni single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (Ni-SAD). There were two dominant lattices present, only the weaker one gave significant anomalous signal, as it could be consistently processed through the whole oscillation range. Phasing and initial model building was done using HKL-3000 integrated with SHELXD, SHELXE, MLPHARE, BUCCANEER, and other auxiliary programs from CCP4.

The initial model was used as a model for a molecular replacement (MR) to solve the KanJ-IOD dataset, the refined KanJ-IOD model was used as an MR model to determine the remaining structures, and it was used as a basis for further refinement of the KanJ-Ni model.

Two lattices present in the KanJ-Ni-αKG-RIB datasets were integrated separately and scaled together using 1–125° from the first (stronger) lattice and 1–220° from the second lattice. For this dataset, the radiation dose model based on the fitted B factors [28] was used instead of the standard linear one.

Models were inspected and rebuilt using coot [57], pymol [58], and molprobity [36] to check the quality of the model. The analysis of the secondary structure was carried out using the stride [59], and protein–ligand interactions were analyzed using ligplot [60].

Comparison of sequences and alignment of KanJ homologous proteins

Sequence identity was analyzed using pdbefold [61], and alignment with KanJ homologous proteins Ftmf, AsqJ, and PhyH was done with cobalt [62].

Enzymatic activity determination

Reaction mixtures contained KanJ (12 μM), antibiotic (kanamycin B, ribostamycin, or neamine, each 1 mm, (Sigma Aldrich, cat. nr. B5264, R2250, N0300000, respectively)), αKG (1 mm, disodium salt, Sigma Aldrich, cat. nr. 75892), Fe2(SO4)3 (120 μM, Sigma Aldrich, cat. nr. 215422) in HCl, and Bis-Tris (300 mm pH = 6.3, 7.0, 7.5, Roth, cat. nr. 9140). To monitor reactions (at 28°C), samples were collected at 0, 15, and 60 min of incubation. Reactions were stopped by addition of 96% ethanol in 1:1 v/v ratio, and the precipitated enzyme was separated by centrifugation (2600 g, 20 min). Supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plates, diluted 10 times with water, and analyzed by HPLC-MS on Agilent Infinity 1290 with MS Agilent 6460 Triple Quad tandem mass spectrometer with Agilent Jet Stream ESI interface in positive mode (Agilent, St. Clara, CA, USA). Nitrogen at a flow rate of 10 L·min−1 was used as the drying gas and for collision-activated dissociation. Drying gas and sheath gas temperatures were set to 350°C. Capillary voltage was set to 3500 V, whereas the nozzle voltage was set to 500 V. The compounds were detected in the multiple reaction monitoring mode of the tandem mass spectrometer (Table 3). Analysis was conducted on Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 (150 mm 9 4.6 mm, 5 um) column with an isocratic flow of mobile phase composed of 5 mm nonafluoropentanoic acid in H2O and acetonitrile mixed in (v/v) ratio 65:35. The flow rate was 1 mL·min−1. Injection volume was 5 μL. Obtained retention times were 3.7 and 2.5 min for kanamycin B and oxo-kanamycin B, 2.6 and 1.7 min for ribostamycin and oxo-ribostamycin, 2.7 and 2.0 min for neamine and oxo-neamine, respectively.

Table 3.

Multiple reaction monitoring m/z values applied for detection of antibiotics and their derivatives

| Antibiotic | m/z [M + H]+ | m/z MRM transitions |

|---|---|---|

| Kanamycin B | 484 | 205, 324, 163 |

| Oxo-kanamycin | 483 | 239, 304, 163 |

| Ribostamycin | 455 | 114, 68, 161, 163 |

| Oxo-ribostamycin | 454 | 286, 371, 239 |

| Neamine | 323 | 114, 161, 80, 163 |

| Oxo-neamine | 322 | 102, 84, 163, 85 |

Metal identification

Purified protein samples were denatured with HNO3 (3.6%, 0.5h, 30°C) [63] and centrifuged (14000 g, 5 min). Supernatant was collected and subjected to ICP-OES analysis performed using Plasma 40 (PerkinElmer) for three samples obtained in separate purification processes.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

As a preparatory step for ITC analysis, protein sample without iron and αKG was prepared. To remove iron and ketoglutarate and to assure uniform protein saturation with nickel, KanJ was dialyzed in four successive steps. 1) dialysis into a buffer A (10 mm HEPES and 50 mm NaCl (pH = 7.5)) with EDTA (5 mm); 2) dialysis into a buffer A; 3) dialysis into buffer A with added nickel sulfate (5 mm); and 4) dialysis into buffer A. Subsequently, protein (1 mm) was incubated for 30 min. with NOG (2 mm) to obtain binary complex KanJ-NOG and measure the formation of a ternary complex KanJ-NOG–aminoglycoside.

Aminoglycoside titration into the KanJ protein in the presence of NOG was measured at three different pH values 6.2, 7.5, and 8.2 to check the influence of ionization state of a ligand on binding to the protein. pKa values of the amino groups of tested antibiotics fall into this pH range. In our experiments, we used kanamycin B, ribostamycin, and neamine. All experiments were carried out at 25°C using a MicroCal iTC200 instrument (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, England) in buffers with 50 mm NaCl in 1) 10 mm Bis-Tris (pH 6.2), 2) 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), or 3) 10 mm Tris (pH 8.2).

All ligands used in the measurements were freshly prepared by dissolving in selected buffers. For NOG, a twofold excess of the ligand to protein was used. All samples were degassed for 15 minutes. The protein concentration in the cell was 100 lM. The syringe was loaded with a 1 mm ligand solution. In each experiment, protein was titrated for 5 sec. with the first injection of 1.5lL and eighteen following injections of 1.8 lL ligand solution, each with 180-sec. intervals between two titrations. The experiments were performed in the high-gain mode with the syringe stirring speed 350 rpm. Raw data were processed and then fit using MicroCal Origin software.

Molecular dynamic simulations

40 ns of molecular dynamic simulation was carried out for one monomer of KanJ (chain E) in a complex with kanamycin B by means of Amber14 [64] software and employing amber ff03 force field [65]. Protonation states of residues at pH 7.0 were checked with PDB2PQR server, version 2.1.1 [66] with implemented propka [67,68] software for pKa calculations; the latter predicted no unexpected protonation states. The protonation states of kanamycin B amino groups were first assigned to be -NH3+ for all. However, the amino group bound to C3 of the ring B has a pKa = 6.28 at 25°C [49], whereas the protonation state of the amino group that is removed in the reaction (bound to C2’) may affect the reaction energetics [69]. Hence, in parallel three separate MD simulations were performed: (a) for a fully protonated model of kanamycin B, (b) with a neutral charge at the amino group bound to C3 (ring B), and (c) a model with both C3-NH2, C2’-NH2 groups charge neutral.

Starting geometry was taken from the crystal structure deposited under PDB ID: 6S0W, and it was completed with missing residues at the N and C termini based on chain B and F (residues 1–2 and 274–285, respectively). Coordinates of α-ketoglutarate were taken from the crystal structure of KanJ in a complex with ribostamycin and α-ketoglutarate (PDB ID: 6S0S). In the next step, succinate and oxoferyl were modeled in an active center; for the oxo ligand in its both plausible positions, that is, trans to His132 or trans to His219. Missing force field parameters for the active center were derived from QM calculation done with B3LYP-D3/ lacv3p + with empirical dispersion GD3 correction and PCM solvent model (r = 1.40 Å, ε = 4.0 [70]) that were performed with the Gaussian 09 [71] according to the procedure described previously [72]). The protein was placed inside a cube filled with water molecules modeled by the TIP3P model with at least a 10 Å distance between the protein and the face of the cube [73]. All three systems were minimized in three steps: in the first run, the complex was restrained with a 500 kcal/(mol Å2) harmonic potential, while the positions of water and the Na+ ions were optimized. Next, the protein was restrained with a 10 kcal/(-mol·Å2) potential, and in the third step, the whole system was minimized with no restraints. In the following step, the systems were heated to 300 K under constant volume conditions over 100 ps and their density equilibrated during 1 ns constant pressure dynamic simulations employing a restraining potential of 1 kcal/(mol·Å2) for protein backbone. The final production MD simulations were carried out with constant temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 atm) under periodic boundary conditions using a 2-fs time step performed with Langevin dynamics, isotropic position scaling, SHAKE algorithm to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms, and the Particle Mesh Ewald method for the long-range electrostatics.

DFT calculations

The last 22 ns of the stable part of MD simulation trajectory for the system with the oxo ligand placed trans to His219 was clustered into 5 groups according to the geometry of the active center (antibiotic, His132, His219, Asp134, Asn120, Cys150 Asn73, Gln80, Gln129, Glu135, Fe(II), succinate). Starting geometry for the DFT cluster model of the active site (Fig. 5D) was derived from a representative snapshot of the most populated cluster by replacing Cα (or Cγ for Arg) with hydrogen atom and discarding other backbone atoms. The positions of these H atoms were kept fixed during geometry optimization. The model consisted of 133 atoms representing side chains of Asn73, Gln80, His132, Asp134, Asp152, Arg213,His219, Arg230, ferryl species, succinate, the key fragment of the substrate antibiotic, and two water molecules. Only the A ring of kanamycin B was considered in the model as the catalytic reaction engages only this part of the antibiotic. Geometry optimizations were performed using the hybrid density functional B3LYP-D3 with empirical dispersion GD3 correction and double-dzeta basis set lacvp. The polarization effects of the solvent were included using the self-consistent reaction field (SCRF) method, with the probe radius r = 1.40 Å and the dielectric constant ε = 4.0, modeling a protein surrounding. Final B3LYP-D3 electronic energies of stationary points were calculated using the cc-pVTZ(-f) basis set on all atoms of main group elements and lacv3p+ for metal ion and reported values were corrected with ZPE. Total charge of the system was +2, and the electronic spin state was quintet. Atomic spin populations used to monitor changes in oxidation states were calculated from the Mulliken population analysis.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Predicted ions for kanamycin B.

Table S2. Predicted ions for oxo-kanamycin B.

Table S3. Predicted ions for ribostamycin.

Table S4. Predicted ions for oxo-ribostamycin.

Table S5. Predicted ions for neamine.

Table S6. Predicted ions for oxo-neamine

Fig. S1. Alignment of KanJ homologous family PhyH proteins by sequence and structure with family representants

Fig. S2. Resolution of kanamycin B from KanJ product oxo-kanamycin B

Fig. S3. Spectrum collected for oxo-kanamycin B

Fig. S4. Spectrum collected for kanamycin B

Fig. S5. Generation of ion products for kanamycin B

Fig. S6. Generation of ion products for oxo-kanamycin B

Fig. S7. Calculated ions obtained from MS/MS fragmentation for kanamycin B and oxo-kanamycin B

Fig. S8. Resolution of ribostamycin from KanJ product oxo-ribostamycin

Fig. S9. Spectrum collected for oxo-ribostamycin.

Fig. S10. Spectrum collected for ribostamycin

Fig. S11. Generation of ion products for ribostamycin

Fig. S12. Generation of ion products for oxo-ribostamycin

Fig. S13. Calculated ions obtained from MS/MS fragmentation for ribostamycin and oxo-ribostamycin.

Fig. S14. Resolution of neamine from KanJ product oxo-neamine.

Fig. S15. Spectrum collected for oxo-neamine.

Fig. S16. Spectrum collected for neamine.

Fig. S17. Generation of ion products for neamine.

Fig. S18. Generation of ion products for oxo-neamine.

Fig. S19. Calculated ions obtained from MS/MS fragmentation for neamine and oxo-neamine.

Acknowledgements

This research project was supported by grant No UMO-2014/15/B/NZ1/03331 from the National Science Centre, Poland and partly by grant No R01GM117325 from the National Institutes of Health, USA. This research was supported in part by PL-Grid Infrastructure. Computations were performed at Academic Computer Centre Cyfronet AGH.

TB. and BM. thank Prof. Krzysztof Lewiński and Dr Katarzyna Kurpiewska for the help in the protein crystallization and Prof. Maksymilian Chruszcz for discussion.

XRD results shown in this report are derived from work performed at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center (SBC) at the Advanced Photon Source. SBC-CAT is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02–06CH11357.

We greatly acknowledge the joint consortium ‘Interdisciplinary Centre of Physical, Chemical and Biological Sciences’ of ICSC PAS and INP PAS for providing the access to Agilent 1290 Infinity System with automatic autosampler and MS Agilent 6460 Triple Quad Detector.

Abbreviations

- αKG

α-ketoglutarate

- 2-DOS

2-deoxystreptamine

- DFT

Density Functional Theory

- DSBH

double-stranded β-helix

- KAN

kanamycin B

- MD

Molecular dynamics

- NEA

neamine

- ODD

Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase

- RIB

ribostamycin

Footnotes

Databases

Structural data are available in PDB database under the accession numbers: 6S0R, 6S0T, 6S0U, 6S0W, 6S0V, 6S0S. Diffraction images are available at the Integrated Resource for Reproducibility in Macromolecular Crystallography at http://proteindiffraction.org under DOIs: 10.18430/m36s0t, 10.18430/m36s0u, 10.18430/m36s0r, 10.18430/m36s0s, 10.18430/m36s0v, 10.18430/m36s0w. A data set collection of computational results is available in the Mendeley Data database under DOI: 10.17632/sbyzssjmp3.1 and in the ioChem-BD database under DOI: 10.19061/iochem-bd-4-18.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

References

- 1.Umezawa H, Ueda M, Maeda K, Yagishita K, Kondo S, Okami Y, Utahara R, Osato Y, Nitta K & Takeuchi T (1957) Production and isolation of a new antibiotic: kanamycin. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 10, 181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstein MJ, Luedemann GM, Oden EM, Wagman GH, Rosselet JP, Marquez JA, Coniglio CT, Charney W, Herzog HL & Black J (1963) Gentamicin, 1 a new antibiotic complex from micromonospora. J Med Chem 6, 463–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waksman SA (1953) Streptomycin: background, isolation, properties, and utilization. Science 118, 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krause KM, Serio AW, Kane TR & Connolly LE (2016). Aminoglycosides: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6, a027029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker B & Cooper MA (2013) Aminoglycoside antibiotics in the 21st century. ACS Chem Biol 8, 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudo F & Eguchi T (2016) Aminoglycoside antibiotics: new insights into the biosynthetic machinery of old drugs. Chem. Rec 16, 4–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sucheck SJ & Shue YK (2001) Combinatorial synthesis of aminoglycoside libraries. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 4, 462–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi K, Caldwell SJ, Fong DH & Berghuis AM (2013) Prospects for circumventing aminoglycoside kinase mediated antibiotic resistance. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter JM & Tang Y (2012) Synthetic biological approaches to natural product biosynthesis. Curr Opin Biotechnol 23, 736–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global WHO (2017) Tuberculosis report. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rinehart KLJ & Stroshane RM (1976) Biosynthesis of aminocyclitol antibiotics. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 29, 319–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umezawa H (2006) Kanamycin: its discovery. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 76, 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams E, De Bie E, Roets E & Hoogmartens J (1996) Isolation and identification of a new kanamycin component. Eur J Pharm Sci 4, S110. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salian S, Matt T, Akbergenov R, Harish S, Meyer M, Duscha S, Shcherbakov D, Bernet BB, Vasella A, Westhof E et al. (2012) Structure-activity relationships among the kanamycin aminoglycosides: role of ring I hydroxyl and amino groups. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56, 6104–6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kharel MK, Subba B, Basnet DB, Woo JS, Lee HC, Liou K & Sohng JK (2004) A gene cluster for biosynthesis of kanamycin from Streptomyces kanamyceticus: comparison with gentamicin biosynthetic gene cluster. Arch Biochem Biophys 429, 204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Y, Zhang Q & Deng Z (2017) Parallel pathways in the biosynthesis of aminoglycoside antibiotics. F1000Research, 6, 723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JW, Park SR, Nepal KK, Han AR, Ban YH, Yoo YJ, Kim EJ, Kim EM, Kim D, Sohng JK et al. (2011) Discovery of parallel pathways of kanamycin biosynthesis allows antibiotic manipulation. Nat Chem Biol 7, 843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sucipto H, Kudo F & Eguchi T (2012) The last step of kanamycin biosynthesis: Unique deamination reaction catalyzed by the ketoglutarate-dependent nonheme iron dioxygenase KanJ and the NADPH-dependent reductase KanK. Angew Chemie – Int Ed 51, 3428–3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin X & Zabriskie TM (2004) VioC is a non-heme iron, α-ketoglutarate-dependent oxygenase that catalyzes the formation of 3S-hydroxy-L-arginine during viomycin biosynthesis. ChemBioChem 5, 1274–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almabruk KH, Asamizu S, Chang A, Varghese SG & Mahmud T (2012) The α-ketoglutarate/Fe IIdependent dioxygenase VldW is responsible for the formation of validamycin B. ChemBioChem 13, 2209–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu B, Wijma HJ, Song L, Rozeboom HJ, Poloni C, Tian Y, Arif MI, Nuijens T, Quaedflieg PJLM, Szymanski W et al. (2016) Versatile peptide C-terminal functionalization via a computationally engineered peptide amidase. ACS Catal 6, 5405–5414. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez S & Hausinger RP (2015) Catalytic mechanisms of Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases. J Biol Chem 290, 20702–20711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purpero V & Moran GR (2007) The diverse and pervasive chemistries of the alpha-keto acid dependent enzymes. J Biol Inorg Chem 12, 587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hausinger RP (2004) Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylases and related enzymes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 39, 21–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prescott AG & Lloyd MD (2000) The iron(II) and 2-oxoacid-dependent dioxygenases and their role in metabolism (1967 to 1999). Nat Prod Rep 17, 367–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garneau-Tsodikova S & Labby KJ (2016) Mechanisms of resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics: overview and perspectives. Med Chem Commun 7, 11–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z & Chruszcz M (2006) HKL-3000: The integration of data reduction and structure solution – From diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr 62, 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borek D, Cymborowski M, Machius M, Minor W & Otwinowski Z (2010) Diffraction data analysis in the presence of radiation damage. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 426–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheldrick GM &IUCr (2008) A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr Sect A Found Crystallogr 64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cowtan K (2006) The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr 62, 1002–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vagin A, Teplyakov A &IUCr (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr 66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porebski PJ, Cymborowski M, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M & Minor W (2016) Fitmunk : improving protein structures by accurate, automatic modeling of sidechain conformations. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Struct Biol 72, 266–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murshudov GN, Skubák P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F & Vagin AA (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr 67, 355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AGW, McCoy A et al. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grabowski M, Cymborowski M, Porebski PJ, Osinski T, Shabalin IG, Cooper DR & Minor W (2019) The integrated resource for reproducibility in macromolecular crystallography: experiences of the first four years. Struct Dyn 6, 064301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS & Richardson DC (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young JY, Westbrook JD, Feng Z, Sala R, Peisach E, Oldfield TJ, Sen S, Gutmanas A, Armstrong DR, Berrisford JM et al. (2017) OneDep: unified wwPDB system for deposition, biocuration, and validation of macromolecular structures in the PDB archive. Structure 25, 536–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan W, Song H, Song F, Guo Y, Wu C-H, Sae Her A, Pu Y, Wang S, Naowarojna N, Weitz A et al. (2015) Endoperoxide formation by an α-ketoglutarate-dependent mononuclear non-haem iron enzyme. Nature 527, 539–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 39.Bräuer A, Beck P, Hintermann L & Groll M (2016) Structure of the dioxygenase AsqJ: mechanistic insights into a one-pot multistep quinolone antibiotic biosynthesis. Angew Chemie – Int Ed 55, 422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aik W, McDonough MA, Thalhammer A, Chowdhury R & Schofield CJ (2012) Role of the jelly-roll fold in substrate binding by 2-oxoglutarate oxygenases. Curr Opin Struct Biol 22, 691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horton JR, Upadhyay AK, Hashimoto H, Zhang X & Cheng X (2011) Structural basis for human PHF2 jumonji domain interaction with metal ions. J Mol Biol 406, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chowdhury R, Sekirnik R, Brissett NC, Krojer T, Ho C, Ng SS, Clifton IJ, Ge W, Kershaw NJ, Fox GC et al. (2014) Ribosomal oxygenases are structurally conserved from prokaryotes to humans. Nature 510, 422–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krishnan S & Trievel RC (2013) Structural and functional analysis of JMJD2D reveals molecular basis for site-specific demethylation among JMJD2 demethylases. Structure 21, 98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Couture J-F, Collazo E, Ortiz-Tello PA, Brunzelle JS & Trievel RC (2007) Specificity and mechanism of JMJD2A, a trimethyllysine-specific histone demethylase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14, 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porebski PJ, Sroka P, Zheng H, Cooper DR & Minor W (2018) Molstack-Interactive visualization tool for presentation, interpretation, and validation of macromolecules and electron density maps. Protein Sci 27, 86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Z, Ren J, Stammers DK, Baldwin JE, Harlos K & Schofield CJ (2000) Structural origins of the selectivity of the trifunctional oxygenase clavaminic acid synthase. Nat Struct Biol 7, 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walter F, Vicens Q & Westhof E (1999) Aminoglycoside–RNA interactions. Curr Opin Chem Biol 3, 694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park JW, Ban YH, Nam S-J, Cha S-S & Yoon YJ (2017) Biosynthetic pathways of aminoglycosides and their engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol 48, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuentes-Martínez Y, Godoy-Alcántar C, Medrano F, Dikiy A & Yatsimirsky AK (2010) Protonation of kanamycin A: detailing of thermodynamics and protonation sites assignment. Bioorg Chem 38, 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freire F, Cuesta I, Corzana F, Revuelta J, González C, Hricovini M, Bastida A, Jiménez-Barbero J & Asensio JL (2007) A simple NMR analysis of the protonation equilibrium that accompanies aminoglycoside recognition: dramatic alterations in the neomycin-B protonation state upon binding to a 23-mer RNA aptamer. Chem Commun 174–176. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Andac CA, Stringfellow TC, Hornemann U & Noyanalpan N (2011) NMR and amber analysis of the neamine pharmacophore for the design of novel aminoglycoside antibiotics. Bioorg Chem 39, 28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kooistra SM & Helin K (2012) Molecular mechanisms and potential functions of histone demethylases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13, 297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen F, Tang Q, Bian K, Humulock ZT, Yang X, Jost M, Drennan CL, Essigmann JM & Li D (2016) Adaptive response enzyme AlkB preferentially repairs 1-methylguanine and 3-methylthymine adducts in double-stranded DNA. Chem Res Toxicol 29, 687–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anand R & Marmorstein R (2007) Structure and mechanism of lysine-specific demethylase enzymes. J Biol Chem 282, 35425–35429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD & Bairoch A (2005) Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (Walker JM, ed), pp. 571–607. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Otwinowski Z & Minor W (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Emsley P & Cowtan K (2004) Coot : model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeLano WL (2002) The PyMOL molecular graphics system.