Abstract

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a useful technique, only a few studies have investigated the dynamic behavior of small subjects using MRI owing to constraints such as experimental space and signal amount. In this study, to acquire high-resolution continuous three-dimensional gravitropism data of pea (Pisum sativum) sprouts, we developed a small-bore MRI signal receiver coil that can be used in a clinical MRI and adjusted the imaging sequence. It was expected that such an arrangement would improve signal sensitivity and improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the acquired image. All MRI experiments were performed using a 3.0-T clinical MRI scanner. An SNR comparison using an agarose gel phantom to confirm the improved performance of the small-bore receiver coil and an imaging experiment of pea sprouts exhibiting gravitropism were performed. The SNRs of the images acquired with a standard 32-channel head coil and the new small-bore receiver coil were 5.23±0.90 and 57.75±12.53, respectively. The SNR of the images recorded using the new coil was approximately 11-fold higher than that of the standard coil. In addition, when the accuracy of MR imaging that captures the movement of pea sprout was verified, the difference in position information from the optical image was found to be small and could be used for measurements. These results of this study enable the application of a clinical MRI system for dynamic plant MRI. We believe that this study is a significant first step in the development of plant MRI technique.

Keywords: dynamic imaging, gravitropism, MRI, signal receiver coil

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems, currently installed in several hospitals worldwide, are used to diagnose various diseases (He et al. 2018; Papanicolas et al. 2018). Especially in Japan, the dissemination of the MRI system in the health service is remarkable. However, the long waiting time for an MRI examination may stretch to several months (Matsumoto et al. 2015). Therefore, an increase in the number of MRI systems is expected in the future. MRI is a non-invasive medical imaging system that obtains morphological and functional images for diagnosis in various parts of the body, such as the brain, internal organs, blood vessels, and muscles. Moreover, it is suitable for post-surgery follow-up examinations because it provides useful information for various diagnoses without using a contrast agent. In recent years, functional MRI (fMRI) for studying brain functions has been developed, and its application in various fields, such as neuroscience, psychiatry, and psychology, has yielded a considerable amount of research data (Abbasi et al. 2020; Achterberg et al. 2020; Saker et al. 2020). An MRI system uses magnetic fields and radiofrequency (RF) pulses to acquire signals from nuclear spins of protons in a subject and processes the signals to create images. Although X-ray computed tomography (CT) is a similar in vivo image acquisition system, subjects undergoing an MRI scan are not exposed to X-rays, unlike a CT system.

Although MRI is used in various fields, studies in which it has been used for investigating the dynamic behavior of small-sized objects such as plants, are rare in the literature. MRI can take 3D images without blind spots, and is capable of collecting structural and functional information of the subjects. MRI data has the potential to acquire tissue structure data and is highly versatile. CT systems are unsuitable for collecting dynamic data because of the high amount of X-ray exposure. Hence, the use of an MRI device for acquiring dynamic data in plants becomes significant. An MRI, specifically for animal experiments, was used for imaging small objects in small animals (Agafonova et al. 2008; Tan et al. 2012). However, imaging an object with significant movement, such as gravitropism (Morita 2010; Sack 1991), using an animal-MRI system is difficult owing to its shape and insufficient experimental space. In addition, the basic imaging methods for acquiring MR signals in such an MRI system are not diverse. In contrast, a clinical MRI system has sufficient space inside the imaging device and a considerable number of imaging sequences. The signal-receiving coil attached to the clinical MRI is intended for humans (Sengupta et al. 2016). Therefore, the signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) of the acquired images of a small object using a clinical MRI are poor and, hence, a clinical MRI is not suitable for the image acquisition of a small object (Keil et al. 2011). It is not possible to image the movement of pea (Pisum sativum) sprouts with the conventional signal-receiving coil of clinical MRI systems. Therefore, a new type of signal-receiver coil is required for imaging small objects.

In this study, to acquire high-resolution continuous 3D gravitropism data of pea sprouts, we developed a small-bore MRI signal receiver coil that can be used in a clinical MRI and adjusted the imaging sequence. These arrangements were expected to result in increased signal sensitivity and improved SNR of the acquired images. Moreover, using a clinical MRI system with ample experimental space allowed us to incorporate experimental equipment for generating gravitropism. Finally, we developed a method for acquiring 3D gravitropism time-series data of pea sprouts using the small-bore MRI signal receiver coil and verified the accuracy of the method.

Materials and methods

MRI system and signal receiver coil

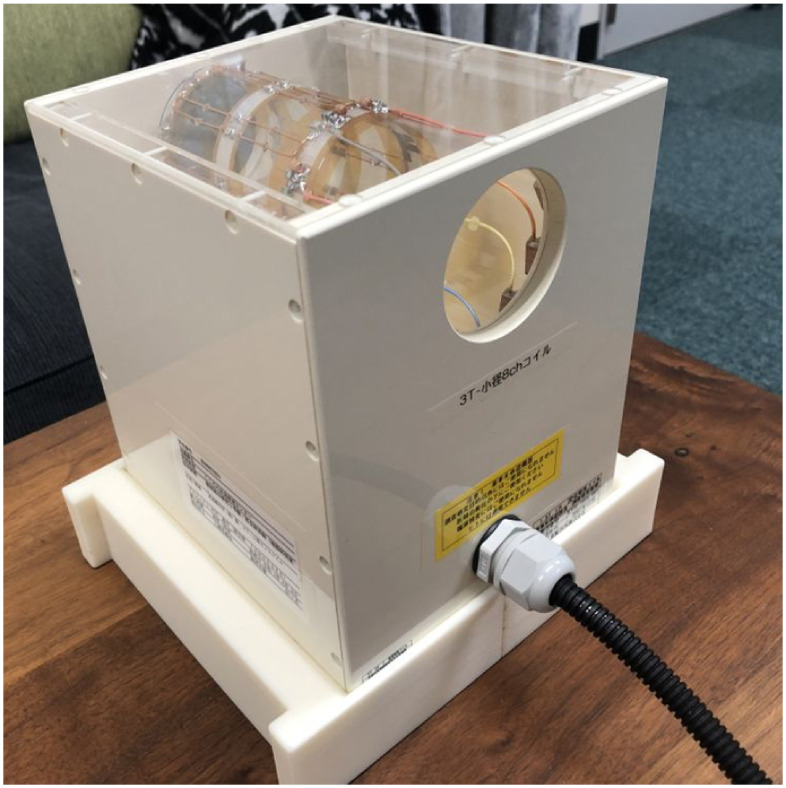

The MRI experiments were performed on a 3.0-T clinical MRI scanner (MAGNETOM Verio, Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany; maximum amplitude: 45 mT/m, slew rate: 200 mT/mms), coupled with a dedicated small-bore receiver coil (Takashima Seisakusho Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 1) for acquiring high-resolution MRI images. The outer dimensions of this signal receiver coil were 150×170×190 mm3, the inner diameter of the coil was 54 mm, and the coil element length was 80 mm. The coil used was a phased-array type, which had a high SNR (Hiratsuka et al. 2007).

Figure 1. Small-bore signal receiver coil for a 3 T-MRI system.

Gravitropism in pea sprouts

A pea sprout (2 mm diameter) was cut at approximately 12 cm from the tip and was kept in a small 20-ml water-containing container covered with a water-absorbing sponge for plants. It was placed in a dedicated small-bore coil in the MRI imaging unit horizontally and fixed so that the tip of the pea sprout could enter the field of view (FoV) of imaging (Figure 2). In addition, the lights in the room were turned off to prevent phototropism. All the equipment used were made of materials that did not cause artifacts on MRI.

Figure 2. The bottle with the pea seedlings was placed horizontally in a small-bore receiver coil and fixed so that the tip of the pea sprout could enter the FoV of imaging. This image was taken outside the MRI imaging room.

MRI measurement and image analysis

In the MRI experiment, SNR comparison experiment using an agarose gel phantom to confirm the improved performance of the small-bore signal receiver coil and an imaging experiment of gravitropism in pea seedlings were performed. The agarose gel phantom was a 30-mm-diameter glass test tube filled with agarose gel (1% pure water). For the comparative imaging study using the agarose gel phantom, an experiment was performed using a dedicated small-bore coil first, and the same experiment was repeated using a high-resolution 32ch head coil, which is primarily used for imaging the brain. The phantom was placed in the center of the imaging field in both experiments, and MRI imaging was performed in the axial section. The T1-weighted three-dimensional volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination (3D-VIBE) sequence was used for the imaging (Pirimoglu et al. 2019; Rofsky et al. 1999; Weiss et al. 2018). The optimized imaging parameters were: repetition time (TR)=15.0 ms, echo time (TE)=5.49 ms, flip angle=15°, bandwidth=150 Hz/pixel, and pixel size=0.20×0.20 mm. The phantom was imaged five times each in the two experiments; the SNR was calculated for all the scanned images, and the SNR due to the two different coils was compared. The following formula (1) is used for SNR calculation.

|

(1) |

In the imaging experiment of the gravitropism in the pea sprout, the T1 weighted 3D-VIBE sequence with imaging parameters of TR=13.0 ms, TE=4.19 ms, flip angle=15°, bandwidth=161 Hz/pixel and pixel size=0.19×0.19 mm was used. To analyze the effect of image distortion on the MRI data, the pea sprout was slowly removed at multiple random times and was photographed with a camera on a horizontal plane. After acquiring the MR images, maximum intensity projection (MIP) processing was applied to those in the sagittal view to create MIP images (Bustamante et al. 2017; Lapeyre et al. 2005; Westerlaan et al. 2005). Because the projection in MIP is two-dimensional, the data are equivalent to horizontal image data. Fusion processing was performed on the optical image taken along the horizontal direction and the MIP image closest in time series. Using 10 sets of aligned data, the differences in the center position in the short-axis direction at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 cm from the tip were analyzed.

Results

Phantom experiment

Figure 3 shows images of the agarose gel phantom acquired with a 32ch head coil and a dedicated small-bore coil. The image obtained with the dedicated small-bore coil (Figure 3B) has a higher resolution. Next, Figure 4 shows the result of the SNR measurement. The SNR of the images acquired with the 32ch head coil was 5.23±0.90 (means±standard deviation) and that acquired with the new coil was 57.75±12.53, which was approximately 11-fold higher. Thus, the significantly higher SNR was obtained in the images acquired using the new small-bore signal receiver coil.

Figure 3. Images of the agarose gel phantom acquired with (A) a 32ch head coil and (B) a dedicated small-bore coil. Evidently, the image obtained with the dedicated small-bore coil (B) is clearer.

Figure 4. SNR measurement results from the MR images of the agarose gel phantom using a 32ch head coil and a dedicated small-bore receiver coil (bars represent standard deviation). Imaging of the agarose gel phantom was performed 5 times each using the two coils. Evidently, the small-bore receiver coil obtains images with a higher SNR.

Imaging of gravitropism of pea sprouts

Figure 5 shows a series of MIP images processed from the data obtained by MR imaging of pea sprouts during gravitropism. The acquisition time of one volume data using MRI was 90 s. We acquired 75 time-series MIP data, but it is difficult to display all the images; therefore, one in every five MIP images is shown in Figure 5 (all MIP images are shown in Supplementary Figure S1). Moreover, for ease of understanding, these images were obtained using two-dimensional data from MIP processing. However, it was possible to construct a 3D model (an example of a 3D model is shown in Supplementary Figure S2). In addition, they had 3D coordinate information. Figure 6 shows a comparison of the position information with the actual image. We observed that the MRI was performed with high accuracy. As seen in Figure 6, the largest deviation is at the measurement point nearest to the tip, owing to the progress of gravitropism while taking out or returning the pea sprout from the MRI system. When compared with MIP data that were older than the actual image, the vertical position of the pea sprout in the actual image was on the upper side. Conversely, when compared with the MIP data newer than the actual image, the vertical position of the pea sprout in the actual image was on the lower side. When the time difference was taken into consideration, a small difference between the position accuracies at the tip and the root.

Figure 5. A time-series of MIP images in sagittal view processed from the data obtained by MR imaging of pea sprouts during gravitropism. The MIP images is displayed every 5 images in the 75 time-series data. The white area in the image represents the pea sprout. The upper left image was taken at the start (0 min) of the time-series data and the lower right image was taken at the end of the time-series data. Clearly scanned images are seen.

Figure 6. Comparison of location information between actual image and MIP image created from MR image. The differences in the center position along the short-axis direction at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 cm from the tip were analyzed (bars represent standard deviation). The values shown are the average values of 10 comparisons (10 sets of actual image and MIP image). It was found that MR imaging was performed with high accuracy.

Discussion

An MRI system, which is an imaging device that scans an image by applying the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) phenomenon (Lauterbur 1973; Mansfield and Grannell 1975), has evolved as a medical imaging system in recent times. Although several animal-MRI devices have been developed, clinical MRI systems are superior to those in terms of various factors, such as stability of image acquisition and diversity of imaging sequences. Moreover, since the available internal space for experiments in animal MRI systems is significantly small, performing dynamic experiments is difficult (Curto et al. 2018; Maramraju et al. 2011). Although a clinical MRI system is more convenient in that aspect, acquiring a significant amount of signal from a small object is difficult because the system is built for humans (Figure 3A). In this study, to solve this problem, we jointly developed a dedicated small-bore receiver coil for scanning small objects. Using this coil, we received a significant amount of NMR signal from a small object and consequently obtained high-resolution images (Figure 3B). A 32ch head coil, which is a signal-receiving device used to image the head (particularly the brain) with high resolution (Franke et al. 2014; Parikh et al. 2011), has a good SNR in this MRI system; however, a small-bore receiver coil offers an SNR that is approximately 11 times higher (Figure 4). Since the usefulness of the small-bore receiver coil is evident in this study, in the future, it can be used in various applications involving other small objects.

Further, the pea sprout with approximately 2 mm diameter is an extremely small subject to be imaged by MRI during gravitropism. For a clinical MRI system, the number of protons is considerably small in such a small subject. However, as shown in Figure 5, the acquisition of these images ensures significant applicability of MRI using the new receiver coil in this study. Furthermore, the spatial information is often distorted because of various factors, such as the distortion of the magnetic field (de Munck et al. 1996). However, the scanned data showed that the positional information is accurate (Figure 6).

Compared with the data from cameras and laser measurements, which are traditionally used in plant observation (Jacques et al. 2013; Rojas-Pierce et al. 2007; Sang et al. 2014), MRI images acquire 3D information inside tissues without blind spots. In addition, we can access the MRI output in the medical image format (DICOM format) to obtain 3D information and easily build a 3D simulation model by interfacing with software, such as the finite element model building software (Peng et al. 2020). Although there is a similar micro CT device that can image the interior of small subjects in three dimensions, the MRI device is superior since the subjects are not exposed to radiation and the device has a large experimental space (Boerckel et al. 2014). Furthermore, an MRI system is superior because of its ability to sensitively identify differences in internal information. Since the X-ray transmittance is reflected in an image in CT (Shah et al. 2018), the change in the pixel value of a soft tissue image is small. However, in MRI, the distinction in a composition is evident because characteristic values such as proton density and relaxation time (T1 and T2) are reflected in the pixel value. In the future, a possibility of associating the brightness value with the detailed composition and the state of the tissue can confirm the difference in the internal composition, and the change in the tissue while scanning the dynamic data. Thus, the MRI apparatus may have a greater advantage in the future. Therefore, we verified that images during the gravitropism of pea sprouts were obtained by a clinical MRI system in this study, which is a meaningful first step toward plant imaging using an MRI. In addition, the imaging sequences and image analysis methods developed here by using a plant in the clinical MRI system can be extended to human imaging using the same clinical MRI. Such a potential implication of this study offers considerable scope for future work in this field.

It has been reported that high-gradient magnetic fields (HGMFs) affect plant tropism (Kuznetsov and Hasenstein 1996). Hence, this can be considered to be a limitation of the proposed method. However, an MRI system mostly generates only a static magnetic field (a gradient magnetic field is not always generated). Therefore, any effect on plant tropism may be small. The vibration and sound produced by an MRI system during imaging can also affect plant gravitropism. The imaging sequence used in this study does not generate a large amount of sound and vibration, but it is not entirely free of them either. While vibration absorbers can be used, they may not be able to solve the problem completely. From an implementation point of view, it is expected that there will be no significant impact of sound or vibrations on this study. However, a more detailed analysis is needed in the future, including studies comparing the gravitropism inside and outside the MRI system.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a method for acquiring time-series 3D data of gravitropism in pea sprouts using a small-bore MRI signal receiver coil and verified the accuracy of the method. The SNRs of the images acquired with a standard 32ch head coil and the new small-bore receiver coil were 5.23±0.90 and 57.75±12.53, respectively. Therefore, SNR was improved by more than 11 times compared to conventional equipment. As a result, it became possible to visualize the pea sprouts during gravitropism via MR images. In addition, when the accuracy of MR imaging that captures the movement of pea sprout was verified, the difference in position information from the optical image was found to be small and could be used for measurements. These results of this study enable the application of a clinical MRI system for dynamic plant MRI. We believe that this study is a significant first step in the development of plant MRI technique.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MEXT KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Plant-Structure Optimization Strategy” with grant number JP19H05366 to R.N. and JP18H05484 and JP18H05489 to T.D. and by JSPS KAKENHI with grant numbers JP19K22963 and JP20H04051 to R.N. This study was conducted using the MRI scanner and related facilities of the Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University.

Supplementary Data

References

- Abbasi N, Duncan J, Rajimehr R (2020) Genetic influence is linked to cortical morphology in category-selective areas of visual cortex. Nat Commun 11: 709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg M, van Duijvenvoorde ACK, van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Crone EA (2020) Longitudinal changes in DLPFC activation during childhood are related to decreased aggression following social rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117: 8602–8610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agafonova IG, Radchenko OS, Novikov VL, Aminin DL, Stonik VA (2008) Magnetic resonance imaging of mouse ehrlich carcinoma growth inhibition by thiacarpine, an analogue of cytotoxic marine alkaloid polycarpine. Magn Reson Imaging 26: 763–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerckel JD, Mason DE, McDermott AM, Alsberg E (2014) Microcomputed tomography: Approaches and applications in bioengineering. Stem Cell Res Ther 5: 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante M, Gupta V, Carlhall CJ, Ebbers T (2017) Improving visualization of 4D flow cardiovascular magnetic resonance with four-dimensional angiographic data: Generation of a 4D phase-contrast magnetic resonance CardioAngiography (4D PC-MRCA). J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 19: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curto S, Faridi P, Shrestha TB, Pyle M, Maurmann L, Troyer D, Bossmann SH, Prakash P (2018) An integrated platform for small-animal hyperthermia investigations under ultra-high-field MRI guidance. Int J Hyperthermia 34: 341–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Munck JC, Bhagwandien R, Muller SH, Verster FC, Van Herk MB (1996) The Computation of MR image distortions caused by tissue susceptibility using the boundary element method. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 15: 620–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke P, Markl M, Heinzelmann S, Vaith P, Burk J, Langer M, Geiger J (2014) Evaluation of a 32-channel versus a 12-channel head coil for high-resolution post-contrast MRI in giant cell arteritis (GCA) at 3 T. Eur J Radiol 83: 1875–1880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Yu H, Shi L, He Y, Geng J, Wei Y, Sun H, Chen Y (2018) Equity assessment of the distribution of CT and MRI scanners in China: A panel data analysis. Int J Equity Health 17: 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsuka Y, Miki H, Kikuchi K, Kiriyama I, Mochizuki T, Takahashi S, Sadamoto K (2007) Sensitivity of an eight-element phased array coil in 3 tesla MR imaging: A basic analysis. Magn Reson Med Sci 6: 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques E, Buytaert J, Wells DM, Lewandowski M, Bennett MJ, Dirckx J, Verbelen JP, Vissenberg K (2013) MicroFilament Analyzer, an image analysis tool for quantifying fibrillar orientation, reveals changes in microtubule organization during gravitropism. Plant J 74: 1045–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil B, Alagappan V, Mareyam A, McNab JA, Fujimoto K, Tountcheva V, Triantafyllou C, Dilks DD, Kanwisher N, Lin W, et al. (2011) Size-optimized 32-channel bain arrays for 3 T pediatric imaging. Magn Reson Med 66: 1777–1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov OA, Hasenstein KH (1996) Intracellular magnetophoresis of amyloplasts and induction of root curvature. Planta 198: 87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapeyre M, Kobeiter H, Desgranges P, Rahmouni A, Becquemin JP, Luciani A (2005) Assessment of critical limb ischemia in patients with diabetes: Comparison of MR angiography and digital subtraction angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185: 1641–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbur PC (1973) Image formation by local induced inter-actions: Examples employing nuclear magnetic resonance. Nature 242: 190–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield P, Grannell PK (1975) Diffraction and microscopy in solids and liquids by NMR. Phys Rev B 12: 3618–3634 [Google Scholar]

- Maramraju SH, Smith SD, Junnarkar SS, Schulz D, Stoll S, Ravindranath B, Purschke ML, Rescia S, Southekal S, Pratte JF, et al. (2011) Small animal simultaneous PET/MRI: Initial experiences in a 9.4 T microMRI. Phys Med Biol 56: 2459–2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Koike S, Kashima S, Awai K (2015) Geographic distribution of CT, MRI and PET devices in Japan: A longitudinal analysis based on national census data. PLoS One 10: e0126036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M (2010) Directional gravity sensing in gravitropism. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 705–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK (2018) Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 319: 1024–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh PT, Sandhu GS, Blackham KA, Coffey MD, Hsu D, Liu K, Jesberger J, Griswold M, Sunshine JL (2011) Evaluation of image quality of a 32-channel versus a 12-channel head coil at 1.5 T for MR imaging of the brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 32: 365–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng MJ, Xu H, Chen HY, Lin Z, Li X, Shen C, Lau Y, He E, Guo Y (2020) Biomechanical analysis for five fixation techniques of Pauwels-III fracture by finite element modeling. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 6: 105491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirimoglu B, Ogul H, Polat G, Kantarci M, Levent A (2019) The comparison of direct magnetic resonance arthrography with volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination sequence and multidetector computed tomography arthrography techniques in detection of talar osteochondral lesions. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 53: 209–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rofsky NM, Lee VS, Laub G, Pollack MA, Krinsky GA, Thomasson D, Ambrosino MM, Weinreb JC (1999) Abdominal MR imaging with a volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination. Radiology 212: 876–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Pierce M, Titapiwatanakun B, Sohn EJ, Fang F, Larive CK, Blakeslee J, Cheng Y, Cutler SR, Peer WA, Murphy AS, et al. (2007) Arabidopsis P-glycoprotein19 participates in the inhibition of gravitropism by gravacin. Chem Biol 14: 1366–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack FD (1991) Plant gravity sensing. Int Rev Cytol 127: 193–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saker P, Carey S, Grohmann M, Farrell MJ, Ryan PJ, Egan GF, McKinley MJ, Denton DA (2020) Regional brain responses associated with using imagination to evoke and satiate thirst. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117: 13750–13756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang DJ, Chen DQ, Liu GF, Liang Y, Huang LZ, Meng XB, Chu JF, Sun XH, Dong GJ, Yuan YD, et al. (2014) Strigolactones regulate rice tiller angle by attenuating shoot gravitropism through inhibiting auxin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 11199–11204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Roebroeck A, Kemper VG, Poser BA, Zimmermann J, Goebel R, Adriany G (2016) A specialized multi-transmit head coil for high resolution fMRI of the human visual cortex at 7 T. PLoS One 11: e0165418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah JP, Mann SD, McKinley RL, Tornai MP (2018) Characterization of CT hounsfield units for 3D acquisition trajectories on a dedicated breast CT system. J XRay Sci Technol 26: 535–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Burden-Gulley SM, Li W, Wu X, Lindner D, Brady-Kalnay SM, Gulani V, Lu ZR (2012) MR molecular imaging of prostate cancer with a peptide-targeted contrast agent in a mouse orthotopic prostate cancer model. Pharm Res 29: 953–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J, Notohamiprodjo M, Martirosian P, Taron J, Nickel MD, Kolb M, Bamberg F, Nikolaou K, Othman AE (2018) Self-gated 4D-MRI of the liver: Initial clinical results of continuous multiphase imaging of hepatic enhancement. J Magn Reson Imaging 47: 459–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerlaan HE, van der Vliet AM, Hew JM, Meiners LC, Metzemaekers JD, Mooij JJ, Oudkerk M (2005) Time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography in the follow-up of intracranial aneurysms treated with Guglielmi detachable coils. Neuroradiology 47: 622–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.