The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented mobilization of healthcare resources including redeployment of healthcare workers within hospitals and from outside institutions.1 Although redeployment was necessary to meet the surge in patients, it will not be without adverse effects. In many ways, the pandemic has exacerbated well understood challenges that exist in our sophisticated health systems. The concept of health system strain and the adverse effects that occur at times of increased demand have been explored in the literature well before the pandemic.2–4 However, the uncertainty around the novel disease process, as well shortage of personnel, and resources such as ventilators, intensive care unit beds, and personal protective equipment (PPE) have introduced a myriad of additional challenges. Treatment injuries that occur in this turbulent time will result from the interaction of these new challenges with complex health systems that are already error prone. Lack of evidence-based treatment guidelines for COVID-19 and suboptimal preparedness provide the perfect milieu to exacerbate patient safety risks5,6 and, as a consequence, could result in a rise in harm events in both COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 patient populations. Health systems that embraced patient safety principles before the pandemic will likely be more able to cope, but all will be affected to some degree. This article discusses how to apply a human factors approach to best respond to the many unprecedented challenges that have been brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic to the healthcare system.

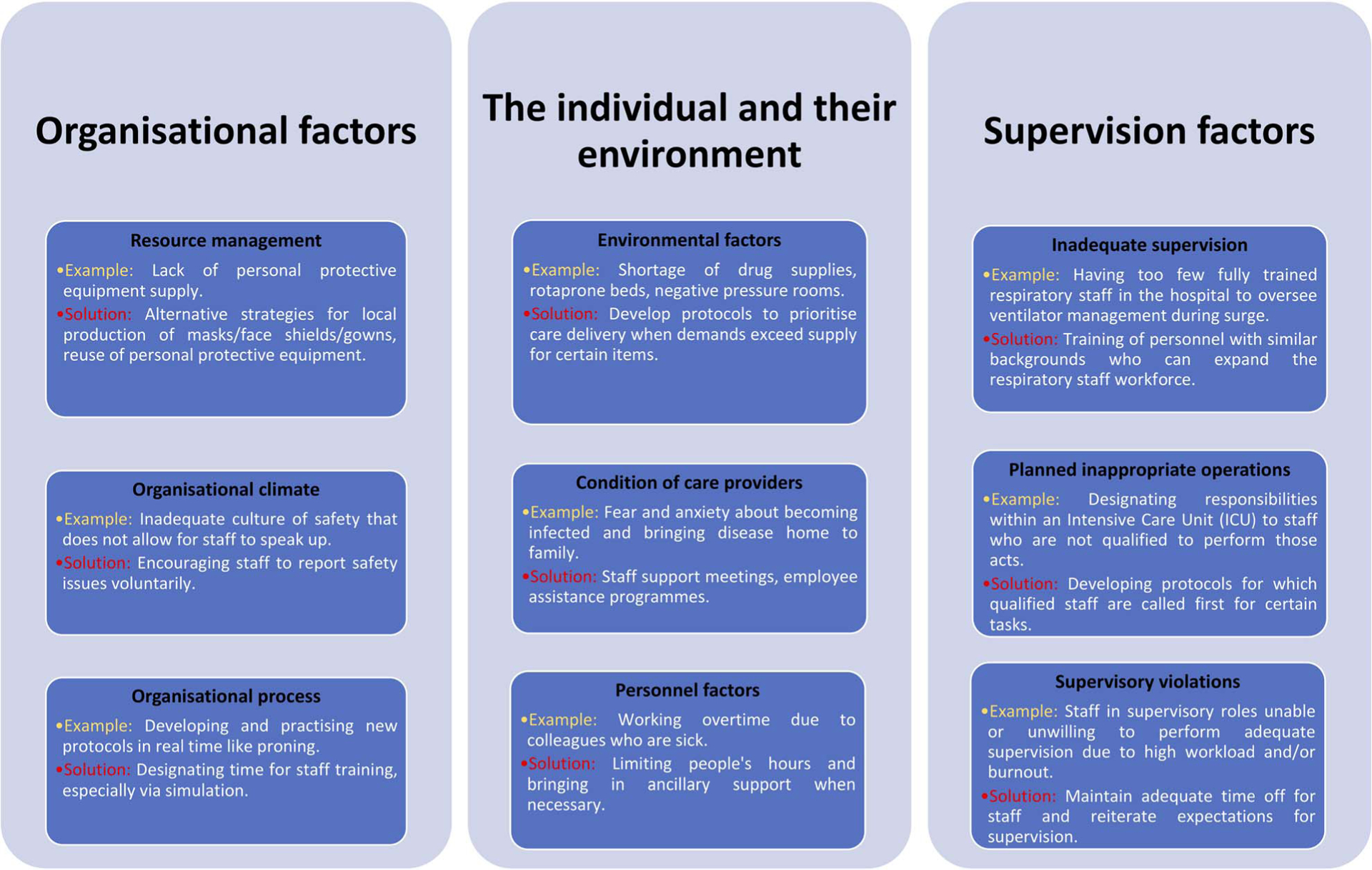

The central principles of patient safety remain preventing errors and redesigning systems when harm events occur. These principles should be applied rigorously as we accommodate the surge in patient load during a pandemic. Foremost, “harm is believed to result from bad systems, not bad people.”7 However, this approach is not meant to de-emphasize the quintessential nature of human-human interactions and human-systems interactions. Human factors are central to safer systems and involve the integration of teamwork, leadership, communication skills, medical technologies, and a culture of safety to support systems and prevent adverse events.8 The Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) provides a framework for examining medical error and treatment injury through the lens of human factors analysis.9 This approach describes 3 levels of failure: organizational factors, individuals and their environments, and supervision factors. Figure 1 presents an adapted HFACS framework with examples pulled from experiences during the initial COVID-19 surge. These experiences are based on our collective international experience.

FIGURE 1.

An adapted HFACS framework during pandemic crises,9 describing 3 levels of failure: organizational factors, individuals and their environments, and supervision factors.

ORGANIZATIONAL FACTORS

Senior management failures are latent and have a direct impact on the other 2 levels of analysis (individuals and supervisory practices). These failures include issues related to resource management, organizational climate, and processes.9 Resource management involves hospital-level decisions aimed to establish a balance between patient safety and time/financial costs. This may be reflected in the lack of PPE during the pandemic, where demand exceeded supply. On the other hand, organizational climate and process refer to the working environment—the policies and protocols development within the hospital and their effects on staff performance. COVID-19 may have arguably introduced an unsafe culture that prevented workers from expressing safety issues voluntarily. The price of poor communication poses a threat to patient safety and may lead to public distrust.10 To mitigate these challenges, we emphasize the need for working environments that encourage staff to speak up (organizational climate) and have a dedicated time to acquire new skills (organizational process) while embracing a patient-centered approach that supports and engages patients and their families. Likewise, strategies at the corporate level may be needed to provide healthcare workers with the PPE needed (resource management). For safety programs to be efficient, safety professionals should gather incident reports, conduct root cause analysis, and assess emerging best practice for COVID-19 diagnosis and infection control as well as monitor such human errors related to organizational factors (safety culture, unclear protocols, and insufficient PPE) to track them down to their specific areas.

HEALTHCARE PERSONNEL AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT

Individuals or human factors are responsible for almost 80% of all aviation accidents. However, holding healthcare workers accountable for the lack of evidence is like focusing on COVID-19 without understanding its pathophysiology. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge the impact of environmental factors on personal behaviors.9 As the pandemic increased the demand for intensive care unit beds, nurses, and doctors were reassigned to areas outside their scope of practice and had to learn new skills. Healthcare workers are among the most valuable resource during the pandemic and providing a safe work environment must be a top priority. Lack of PPE and proper training in donning has been identified as potential causes of healthcare worker infection.11 Studies on the psychological impact of COVID-19 have shown increased levels of anxiety and fatigue among healthcare workers from a multitude of factors.12 These include having to manage a little-understood disease, long hours, increased patient load, psychological stress from having to make difficult triage decisions, and from the death of patients. Every time a healthcare worker is incapacitated, the pool of available personnel to care for patients is further reduced, which in turn increases the workload and stress on the remaining personnel. It is therefore important to develop evidence-based protocols and teamwork strategies to protect the staff’s physical, emotional, and mental health.

SUPERVISION FACTORS

Reason9,13 argues that the lack of supervision can play a critical role in human error events and the 3 categories of supervision factors are highlighted in Figure 1. COVID-19 created severe staff shortages, which result in “planned inappropriate operations” because of the necessity of designating personnel with suboptimal training to perform a task, such as ventilator management. We believe that developing protocols for training personnel of similar backgrounds may ensure sufficient time for supervision and reduce the risk of supervisory violations and inappropriate operations.

PATIENT SAFETY INNOVATIONS DURING THE PANDEMIC

Short-term solutions that tackle specific aspects of patient safety have been developed in various settings during the pandemic. For example, the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, created a dedicated small intubation team for the entire hospital as a measure to reduce medical and human errors associated with nosocomial transmission during the procedure. In addition, they assigned trained safety officers during cardiac arrests to observe donning and doffing of PPE, a task which may be overlooked under such strained capacities. At the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, the telephone numbers for patient rooms were added to the in-house digital handoff tool, Careline. Normally, in a system for tracking vitals, tasks, and sign outs, the system was rapidly updated with icons representing a patient’s COVID-19 status. By clicking the listed number, clinicians on rounds could call into patients’ rooms while standing outside the room, and conduct morning rounds without direct patient contact while a subset of the team performed daily physical examinations.

CONCLUSIONS

Effective response to a pandemic requires policy makers and professionals to acknowledge and examine associated challenges such as the absence of evidence-based tests and treatments and the reassignment of healthcare staff to unfamiliar work environments. The challenges and uncertainties posed by COVID-19 require rapid innovation and iteration, and an environment that seamlessly forges collaboration. We must redesign our organizations, environments, schedules, protocols, and plan for supervision in such a way that promotes the safe delivery of care to patients in the setting of greater uncertainties. We hope that the lessons learned during the pandemic will permanently transform our approach to patient safety.

Acknowledgments

M.A.A. is funded by the Imperial College President’s PhD Scholarship. L.A.C. is funded by the National Institute of Health through NIBIB R01 EB017205.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCluskey PD. Hospitals redeploy thousands of health care workers to respond to COVID-19 crisis. Bostonglobe. 2020. Available at: https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/04/20/business/hospitals-redeploy-thousands-health-care-workers-respond-covid-19-crisis/. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 2.Wilcox ME, Harrison DA, Patel A, et al. Higher ICU capacity strain is associated with increased acute mortality in closed ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anesi GL, Liu VX, Gabler NB, et al. Associations of intensive care unit capacity strain with disposition and outcomes of patients with sepsis presenting to the emergency department. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15: 1328–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers LC, Faridi MK, Currier P, et al. ICU utilization for patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease receiving noninvasive ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zagury-Orly I, Scwartzstein R. Covid-19 - a reminder to Reason. NEJM. 2020;1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.London AJ, Kimmelman J. Against pandemic research exceptionalism. Science. 2020;368:476–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leape L. Patient safety in the era of healthcare reform. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:1568–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carayon P. Patient safety: the role of human factors and systems engineering. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;153:23–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shappell SA, Wiegmann DA. The Human Factor Analysis and Classification System (HFACS). (Report Number DOT/FAA/AM-00/7). Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration; 2000:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraham T. The price of poor pandemic communication. BMJ. 2010; 340:C2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Zhou M, Liu F. Reasons for healthcare workers becoming infected with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:100–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang M, Zhou M, Tang F, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:183–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reason J Human Error. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]