Abstract

There is a pressing need for compounds with broad-spectrum activity against malaria parasites at various life cycle stages to achieve malaria elimination. However, this goal cannot be accomplished without targeting the tenacious dormant liver-stage hypnozoite that causes multiple relapses after the first episode of illness. In the search for the magic bullet to radically cure Plasmodium vivax malaria, tafenoquine outperformed other candidate drugs and was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2018. Tafenoquine is an 8-aminoquinoline that inhibits multiple life stages of various Plasmodium species. Additionally, its much longer half-life allows for single-dose treatment, which will improve the compliance rate. Despite its approval and the long-time use of other 8-aminoquinolines, the mechanisms behind tafenoquine’s activity and adverse effects are still largely unknown. In this Perspective, we discuss the plausible underlying mechanisms of tafenoquine’s antiparasitic activity and highlight its role as a cellular stressor. We also discuss potential drug combinations and the development of next-generation 8-aminoquinolines to further improve the therapeutic index of tafenoquine for malaria treatment and prevention.

Graphical Abstract

Malaria continues to pose a tremendous financial and health burden to the world, accounting for 228 million cases and 405000 deaths in 2018.1 The spreading resistance to available antimalarial drugs and the reduced susceptibility to front-line artemisinin-based combination therapies have slowed the progress of malaria control and elimination. New drugs with a broad-spectrum activity against multiple malaria life cycle stages in various species, including those with multidrug resistance, are desperately needed to overcome emerging drug resistance. These properties are also requisite for an antimalarial agent to satisfy the global target of eradicating malaria.

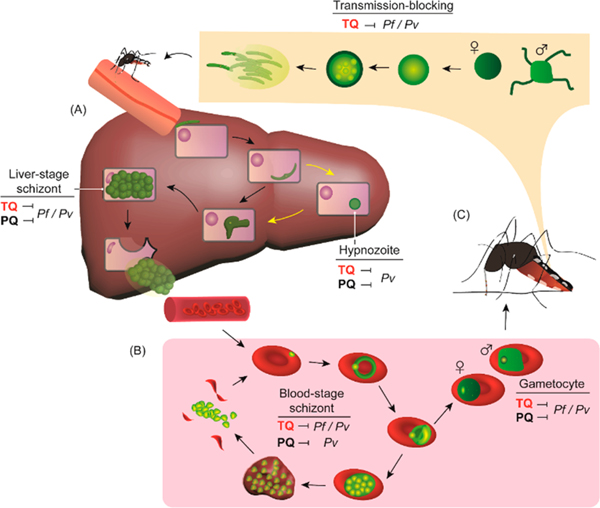

Among the human-infective species, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax are the main culprits in most malaria cases. These apicomplexan parasites are transmitted by female Anopheles mosquitoes when taking a blood meal in which sporozoites (a liver-invasive parasite form) enter the blood circulation and invade hepatocytes. Following the liver-stage schizogony (asexual reproduction by multiple nuclear divisions before cytokinesis), thousands of parasites are released into the bloodstream and invade red blood cells (RBCs). At this time, the merozoites (an RBC-invasive parasite form) develop into blood-stage schizonts that produce 10−36 daughter merozoites capable of further red cell invasion and expansion. During the blood stage, a proportion of merozoites will differentiate into male and female gametocytes which, once taken up by another mosquito, fuse to form zygotes and eventually give rise to sporozoites in the salivary glands of Anopheles mosquitoes.

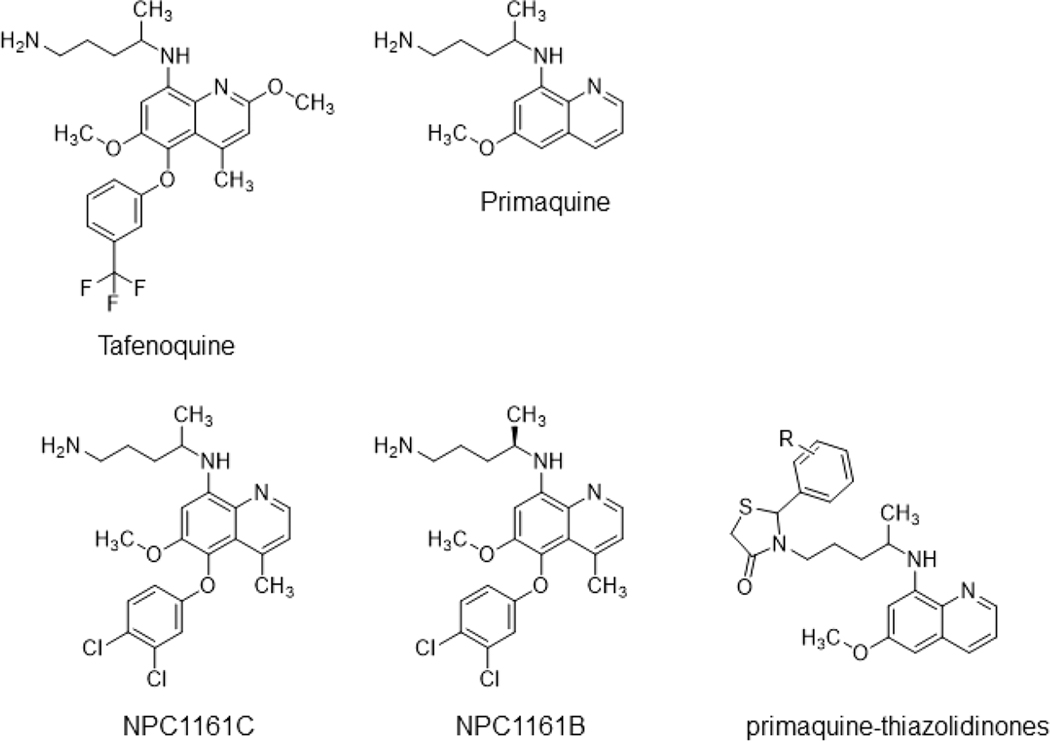

Unlike P. falciparum, a fraction of P. vivax sporozoites can enter a dormant liver stage that causes malaria relapse within a range of weeks to several years following the initial episode of illness. This difficult-to-treat dormant liver stage is attributed to the latent parasite form called a hypnozoite, which is refractory to most antimalarial medications. Mathematical models indicate that the hypnozoite reservoir continues to fuel malaria transmission, and therefore, the goal of elimination cannot be achieved without targeting this reservoir.2−4 In 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration approved tafenoquine for the radical cure (clearing of all parasite forms, including hypnozoites) of P. vivax infection (Krintafel, Kozenis) and for malaria chemoprophylaxis (Arakoda, Kodatef) (Figure 1).5 Before tafenoquine’s approval, the community had been counting on primaquine as the sole antirelapse therapy since its registration in 1952.6 Like primaquine, tafenoquine is an 8-aminoquinoline derivative that shows similar tolerability and efficacy in preventing recurrence of P. vivax malaria,7−9 while in actual clinical settings, tafenoquine is expected to have a higher efficacy due to its superior pharmacokinetic properties. This important feature allows for single-dose treatment, a significant improvement to the standard 14-day primaquine regimen that results in a low compliance rate.10−13 Additionally, tafenoquine has a broad-spectrum activity against liver- and blood-stage schizonts and gametocytes in both P. falciparum and P. vivax, making this drug suitable for malaria prophylaxis (Figure 2).7,14,15 Recently, the evolution of 8-aminoquinolines and the emergence of tafenoquine have been described in detail.7 In this Perspective, we discuss the mechanisms behind tafenoquine’s activity and toxicity, especially from the point of view of drug-induced cellular stresses. We also discuss potential drug combinations and the development of next-generation 8-aminoquinolines for extending the therapeutic window of tafenoquine.

Figure 1.

Structures of tafenoquine and other 8-aminoquinolines.

Figure 2.

Broad-spectrum activity of tafenoquine on different life cycle stages of Plasmodium parasites. Plasmodium parasites are transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes and undergo the (A) liver stage and (B) blood stage in humans. (C) The blood-stage gametocytes are then taken up by another mosquito and eventually develop into the liver-infective form to complete the life cycle. Yellow arrows indicate parasite development (hypnozoite) in P. vivax (Pv) but not in P. falciparum (Pf). TQ, tafenoquine; PQ, primaquine.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION: WHAT IS STRESSING THE PARASITES OUT?

The mechanism of action of tafenoquine remains largely unknown, and currently, there are no known molecular targets for this drug or other 8-aminoquinolines.16−18 Previous clinical data suggest a link between cytochrome P450 isozyme 2D6 (CYP 2D6) and the metabolism/therapeutic activity of primaquine.19−21 This connection was supported by a CYP 2D knockout mouse model in which primaquine failed to prevent Plasmodium berghei infection.22 The causal prophylactic activity (activity against the liver stage of infection) of primaquine was then restored when the human CYP 2D6 gene was introduced.22 Similar experiments suggest that the antiplasmodial activity and pharmacokinetics of tafenoquine require metabolic activation by CYP 2D enzymes.23,24 A more extensive genetic association study could address if the enzymatic activities of CYP 2D6 and other metabolic enzymes dictate the curative efficacy of tafenoquine in humans.14,25

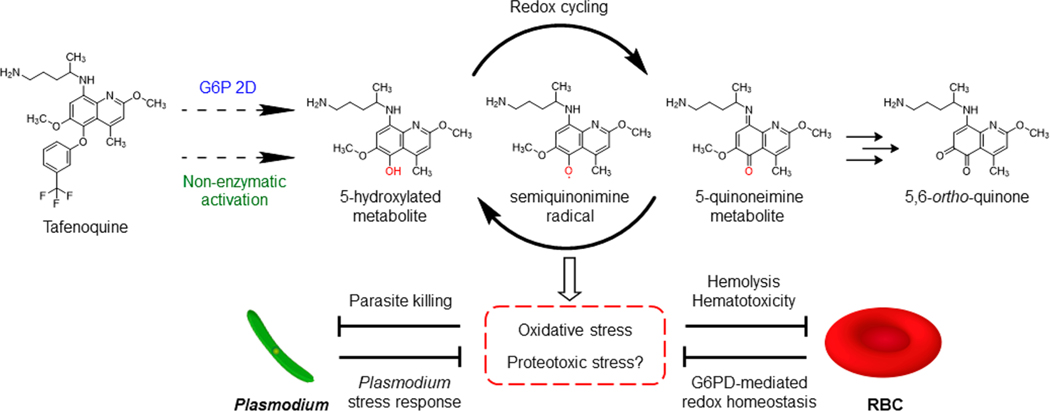

During the dormant stage, Plasmodium parasites generally suppress metabolic and transcriptional activities while exhibiting transcriptionally active redox metabolism and heat shock protein 70 expression, which renders resilience against most antimalarial agents.26 However, tafenoquine and other 8-aminoquinolines seem to have the capability to subvert cellular homeostasis in established hypnozoites. Through the CYP 2D6-mediated metabolic pathway, primaquine is metabolized to multiple hydroxylated species that are unstable and highly redox reactive.7,27,28 These hydroxylated species are transformed into similarly reactive quinoneimine metabolites that can be converted back to the hydroxylated derivatives under aerobic conditions, causing redox cycling and accumulation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).27,29 The buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in parasite-infected hepatocytes may eventually lead to parasite death.5,27,30 The same mode of action was recently found in the bone marrow where primaquine metabolism generated H2O2 to kill gametocytes and blood-stage schizonts.30−32 Given that the antiplasmodial activity of tafenoquine may require CYP 2D activation, production of its reactive metabolites and H2O2 is likely to be involved. Thus far, the most recognized primaquine metabolite responsible for the activity is 5-hydroxyprimaquine, the presence of which is detected by measuring the downstream 5,6-o-quinone product.27,33,34 Unlike primaquine, tafenoquine has a 3-(trifluoromethyl)phenoxy group that prevents position 5 from direct oxidation, conferring the slow elimination and long-acting activity of tafenoquine.35 There was thus speculation that O-dealkylation and oxidation of the 2- and 6-methoxy groups could give rise to the reactive quinoneimine metabolites.35 However, the 5,6-o-quinone metabolite of tafenoquine was also detected in vivo, suggesting the presence of 5-hydroxylated species (Figure 3).24,36 A more complete profiling of tafenoquine metabolism and the enzymes involved would help elucidate its mechanism of action and potentially facilitate future drug design.

Figure 3.

Hypothesized mechanisms underlying the activity and toxicity of tafenoquine. Dashed arrows indicate the production of a hypothetical tafenoquine metabolite via G6P 2D-dependent or -independent pathways.

Redox cycling of hydroxylated primaquine metabolites also generates semiquinonimine radical that may target nucleophiles as well as alkylate parasite proteins and/or other biomolecules.7,27,29,37 However, this potential mechanism remains largely unexplored. Intriguingly, endoperoxides such as artemisinin are potent antimalarial drugs that form carbon-centered radicals to alkylate parasite proteins and unsaturated membrane lipids.38,39 Like 8-aminoquinolines, the mechanism of action of endoperoxides and their molecular targets have long been elusive. Chemoproteomic studies using artemisinin probes attached with clickable alkyne and azide tags have revealed more than one hundred P. falciparum parasite proteins modified by artemisinin.40−42 Similar strategies could be applied to identify protein adducts, if any, of tafenoquine and primaquine. To date, no genetic marker has been found for tafenoquine or primaquine resistance.16,17 Such “resistance” is difficult to determine due to treatment adherence (for primaquine), co-administration with blood schizonticides, and the varying CYP 2D6 activity in the population.23 If parasites with higher tafenoquine or primaquine tolerability could be raised under drug selection, it could generate testable hypotheses about molecular targets. Unfortunately, P. vivax long-term culture has not been achieved given its restricted tropism to invade reticulocytes.35,43,44 Perhaps the recently established Plasmodium cynomolgi continuous culture system45 and tafenoquine’s ability to inhibit the P. falciparum asexual blood stage7 will facilitate future studies to help elucidate the mechanism(s) underlying tafenoquine’s activity and resistance. Because this compound triggers oxidative stress (and potentially proteotoxic stress) in Plasmodium parasites, a systemic change in the parasite stress response machinery may confer tafenoquine tolerance in the parasites.

Deletion of the CYP 2D gene cluster, as described, abolished the causal prophylactic activity of tafenoquine in mice,23,24 yet this genetic deletion did not affect the ability of tafenoquine to inhibit blood-stage schizonts and gametocytes, suggesting a CYP 2D-independent activity for these stages.46 However, this observation does not necessarily indicate a different mode of action for the blood stage. Fasinu and colleagues47 recently showed that primaquine incubated with human RBCs could transform into the 5,6-o-quinone species. Therefore, a non-enzymatic activation of 8-aminoquinolines may exist. Other than ROS production, tafenoquine also caused mitochondrial dysfunction accompanied by increased intracellular Ca2+ levels in the related protozoan parasites Leishmania and Trypanosoma brucei.48,49 Additionally, tafenoquine may trigger eryptosis (programmed cell death of erythrocytes) in Plasmodium-infected RBCs.50,51 Whether these events are downstream of cellular stresses induced by tafenoquine or direct targets of this drug is currently unknown.

MECHANISMS BEHIND TAFENOQUINE’S TOXICITY

The major safety concerns with tafenoquine and other 8-aminoquinolines are their hemolytic toxicity in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)-deficient individuals and the general hematotoxicity (primarily methemoglobinemia) in all patients.7 Methemoglobinemia is characterized by an increased level of methemoglobin that carries oxidized ferric iron (Fe3+) and thus impairs the protein’s oxygen binding capacity.52 Although the elevated methemoglobin level showed no clinical symptoms in tafenoquine-treated patients, severe methemoglobinemia could occur in certain clinical settings such as G6PD deficiency.8,9,53,54 As methemoglobin formation involves hemoglobin oxidation, many oxidizing agents have been recognized as strong inducers of methemoglobinemia.55 Not surprisingly, the oxidative activity of the hydroxylated 8-aminoquinoline metabolites is the main culprit for this adverse event.56−58 Computational analyses further revealed the role of these metabolites as electron donors for hemoglobin-bound oxygen, which then generates H2O2 and methemoglobin.59−61

Tafenoquine can cause severe hemolytic anemia in G6PD-deficient individuals. G6PD deficiency is an inherited X-linked genetic disorder with diverse single-nucleotide polymorphisms that affect G6PD enzyme activity to a varying degree. This genetic abnormality is especially widespread in malaria endemic regions (8% on average with >30% in some malarious countries) and thus affects a relatively large proportion of the population susceptible to malaria infection.62−64 As with primaquine, the hemolytic potential of tafenoquine appears to correlate with G6PD enzyme activity in humans.65,66 Thus, G6PD status in patients needs to be determined prior to prescription, and tafenoquine can be used only in patients having >70% of normal G6PD activity.67 This stipulation is especially challenging in resource-limited countries. G6PD catalyzes the oxidation of glucose 6-phosphate to 6-phosphoglucono-δ-lactone, concomitant with NADPH generation in the cytosol.68 Because human erythrocytes lack mitochondria, these cells heavily rely on G6PD-mediated NADPH production to provide sufficient reducing power against oxidative stress.69,70 As such, G6PD-deficient erythrocytes have lower tolerability to oxidizing agents, including the hydroxylated metabolites of 8-aminoquinolines.71 Studies of G6PD deficiency and primaquine-induced hemolysis indicate that oxidation of hemoglobin and the membrane skeletal proteins, but not lipid peroxidation, leads to the membrane instability and RBC clearance.72−75 This protein oxidation event is accompanied by hemoglobin denaturation and formation of irreversible aggregates called the Heinz bodies. The occurrence of Heinz bodies is associated with the hemolytic toxicity of 8-aminoquinolines.7 However, the drug-induced oxidative stress may not be the only reason for Heinz body formation, given that treatment with different oxidants caused Heinz bodies to a varying degree.7,76 The special relationship between 8-aminoquinoline and Heinz body formation could probably be recapitulated by oxidized phenylhydrazine that interacts with ferrihemoglobin to form ferrihemochrome.7,77−80 Another player would be semiquinonimine radicals generated during redox cycling. These highly reactive intermediates may irreversibly modify hemoglobin via covalently attaching to nucleophilic residues and/or the porphyrin ring, thus aggravating hemoglobin precipitation. The ability to form adducts with the heme porphyrin might be analogous to that of endoperoxide antimalarials.81,82 Biochemical analysis such as mass spectrometry could be useful for examining this hypothesis.83 Overall, the exacerbated accumulation of ROS in G6PD-deficient patients and the molecular events involving tafenoquine metabolites may together damage the RBC membrane to eventually result in hemolytic anemia.

DRUG COMBINATIONS: BOOSTING THE CLINICAL UTILITY OF TAFENOQUINE

The synergism between 8-aminoquinolines and blood schizonticides has been noticed for decades with unknown mechanisms behind the drug−drug interactions.7,31,84 In P. cynomolgi-infected monkeys, co-administration with chloroquine reduced the minimum curative dose of tafenoquine by 10-fold when compared to tafenoquine monotherapy.85 Along tafenoquine’s clinical development path, it had been coupled with chloroquine, the standard of care for P. vivax infection, without the assessment of a possible synergistic effect with other blood schizonticides.8,86 This drug combination is threatened by the establishment and spreading of chloroquine-resistant P. vivax.87 Ideally, tafenoquine should be co-administered with fast-acting blood schizonticides such as artemisinin and its derivatives due to its slow parasite clearance rate.14 Current in vitro evidence suggests synergistic interactions between tafenoquine and artemisinin combination therapies (both artemisinin and its partner drugs) in P. falciparum blood-stage schizonts,88,89 though if artemisinin (and other blood schizonticides) potentiates the radical curative activity or alleviates the toxicity of tafenoquine remains unclear.

The hemolytic toxicity in patients with G6PD deficiency has limited the clinical application of tafenoquine and other 8-aminoquinolines. Although high-throughput screening of detoxifying partner drugs has been proposed, such an assay has not been reported, partly due to the paucity of relevant lead compounds.7 A recent biochemical study identified a G6PD agonist AG1 that can activate wild-type and mutant G6PD enzymes.90 AG1 treatment suppressed drug-induced oxidative stress in zebrafish and human RBCs and exhibited antihemolytic potential with enhanced G6PD activity.90 Testing the ability of AG1 and other G6PD agonists to mitigate the drug-induced hemolysis without compromising the therapeutic activity of tafenoquine is a much-needed next step for the treatment of G6PD-deficient individuals.

NEXT-GENERATION 8-AMINOQUINOLINES

In search of novel 8-aminoquinolines with higher therapeutic indices to replace racemic primaquine, Schmidt and colleagues91 reported that (+)-primaquine was 3−5-fold less toxic than (−)-primaquine, while the capacities of primaquine and its enantiomeric forms to cure P. cynomolgi infection in a relevant non-human primate model remained the same. Later studies further revealed the enantiospecificity of primaquine with varied metabolic, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic behaviors in rhesus monkeys and humans.92−94 Thus, a path toward improved 8-aminoquinolines could be to evaluate the chemotherapeutic indices of individual enantiomers of promising candidates.

An 8-aminoquinoline analogue NPC1161C as a racemic form (also known as WR233078) exhibited superior blood schizonticidal activity with minimal toxicity in a P. berghei mouse model when compared to those of primaquine and tafenoquine (Figure 1).95 This compound also showed excellent radical curative activity against P. cynomolgi infection in monkeys.96 However, NPC1161C induced signs of hematotoxicity in beagles to a level higher than that induced by primaquine and tafenoquine.95 Efforts to study the importance of stereochemistry in the antiparasitic and toxic activities of NPC1161C revealed that the (−)-enantiomer NPC1161B displayed reduced hematotoxicity and improved efficacy compared to those of its racemate.95 NPC1161B has prophylactic activity in the P. berghei mouse model and is potent against P. cynomolgi liver-stage schizonts and hypnozoites. Additionally, this compound inhibits the P. falciparum sexual and asexual blood stages and sporozoite formation in Anopheles mosquitoes.35,97,98 Whether the antirelapse and prophylactic activities of NPC1161B can be translated to human trials would depend on extensive pharmacological and safety profiles in animal models, especially in the setting of G6PD deficiency. To facilitate these steps, an established humanized mouse model with G6PD-deficient RBCs can be used to assess its hemolytic toxicity.99

Given the intimate link between 8-aminoquinolines’ metabolism and their activities/toxicities, numerous primaquine derivatives have been synthesized through modification of the quinoline core and the terminal amino group to improve the therapeutic window.100,101 Many primaquine derivatives showed reduced cytotoxicity in cell cultures in addition to higher potency against the P. falciparum blood stage and P. berghei liver stage in vitro.101 However, few studies have compared the efficacies of these derivatives in multiple Plasmodium life stages, and even fewer have assessed their radical curative activities and the hemolytic toxicity in the context of G6PD deficiency. As one example, a cohort of primaquine-thiazolidinones were generated and shown to suppress rodent and avian malaria transmission (Figure 1).102 Despite the slightly lower activity against P. berghei liver-stage schizonts in vitro and in vivo, the cytotoxicity and hemolytic toxicity were greatly reduced in different cell types as well as G6PD-deficient human RBCs.102 Perhaps similar modifications to tafenoquine or NPC1161B would facilitate the search for safer substitutes for treating G6PD-deficient individuals while retaining their long-acting, antirelapse, and broad-spectrum activities.

OUTLOOK

Since the introduction of the ancestral 8-aminoquinoline plasmochin in the early 1900s, the molecular mechanisms underlying the radical curative activity and the hemolytic toxicity of 8-aminoquinolines have been elusive.7 Technical challenges in studying the dormant liver-stage parasites, the inaccessibility of relevant G6PD-deficient animal models, and the difficult-to-identify metabolites due to their instability contribute to this lack of knowledge.7,35 Undoubtedly, the characterization of parasites with resistance to 8-aminoquinolines would advance our mechanistic understanding, but these have yet to be isolated. When a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of action of 8-aminoquinolines is achieved, it will accelerate next-generation antimalarial drug development and the strategic design of drug combinations. This will allow us to increase the therapeutic utility and antimalarial potency of these drugs, while minimizing the hemolytic toxicity in G6PD-deficient individuals. The ongoing development of P. cynomolgi and P. vivax culture systems,35,45,103 the humanized G6PD-deficient mouse model,99 and the advancing omics-based methods16,17,26,104 should greatly aid in the understanding of such mechanisms.

The standard quantitative assessment of G6PD status is critical for the deployment of 8-aminoquinolines. However, such diagnostics are not easily accessible in resource-limited regions where malaria is endemic.7,105,106 New drugs that can be safely administered to all patients will be crucial for malaria elimination, but the search for these new compounds was hampered by a lack of accessible tools. Recently, significant advances in model systems and screening tools, many spurred by support from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) and the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV), are accelerating the drug discovery process.35 For example, Roth and colleagues107 developed a platform to rapidly identify liver-stage schizonts and hypnozoites in P. vivax-infected primary human hepatocytes, which allows for automated drug screening with higher throughput. Important progress has also been made with the continuous culturing of blood-stage P. cynomolgi, which shares many biological features with P. vivax, including hypnozoite development.45 While clearly an important tool for blood-stage P. cynomolgi drug screening, this long-term culture system may be further developed to promote gametocytogenesis and aid in liver-stage assays.45 Additionally, the advent of humanized mouse models that support complete liver-stage and blood-stage parasite development will provide a more efficient preclinical assessment of candidate drugs.108−110 These methodologies, among others, will accelerate the discovery and development of new lead compounds to facilitate malaria control efforts.

Like endoperoxides, drugs that induce general cellular stresses tend to be among the most effective and useful antimicrobial agents.111,112 Multiple lines of evidence suggest that tafenoquine triggers oxidative stress (and proteotoxic stress) in Plasmodium parasites and G6PD-deficient RBCs.11,24,36,65,99 Although it is unclear whether tafenoquine kills Plasmodium at different life cycle stages in the same manner, tafenoquine’s activity against Leishmania and T. brucei appears to involve ROS production.48,49 Through unknown mechanisms, tafenoquine also has activity against Toxoplasma gondii, Babesia microti, and Pneumocystis carinii.113−115 It is likely that tafenoquine, once activated by CYP 2D enzymes or an alternative pathway, triggers general cellular stresses that then contribute to its broad-spectrum activity. With that being said, a fundamental understanding of how Plasmodium responds to various stresses is important. The front-line antimalarial artemisinin can generate oxidative stress and proteotoxic stress in Plasmodium and effectively kill the parasites.38,39,116 Despite the exceptional potency of artemisinin, P. falciparum with increased tolerability to this drug has been detected in Southeast Asia.117,118 Transcriptomic analyses have shown that genes involved in the unfolded protein response, oxidative stress response, and protein turnover are upregulated in artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum.38,39,119−121 As such, a systemic change in the Plasmodium transcriptional program renders a higher tolerability to drug-induced cellular stress. An in-depth understanding of tafenoquine’s mechanism of action and how Plasmodium reacts to the stress would be imperative. Inhibitors targeting the Plasmodium stress response, such as the parasite proteasome and the TCP-1 ring complex (TRiC), could eventually partner with 8-aminoquinolines in drug combinations to address parasites with high tolerability.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (DP2AI138239 to E.R.D.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- RBC

red blood cell

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- G6PD

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- TQ

tafenoquine

- PQ

primaquine

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Kuan-Yi Lu, Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, School of Medicine, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, United States.

Emily R. Derbyshire, Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, School of Medicine and Department of Chemistry, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).World Malaria Report 2019 (2019) World Health Organization, Geneva: (Licence CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; ). [Google Scholar]

- (2).Roy M, Bouma MJ, Ionides EL, Dhiman RC, and Pascual M. (2013) The potential elimination of Plasmodium vivax malaria by relapse treatment: insights from a transmission model and surveillance data from NW India. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 7, No. e1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).White MT, Karl S, Battle KE, Hay SI, Mueller I, and Ghani AC (2014) Modelling the contribution of the hypnozoite reservoir to Plasmodium vivax transmission. eLife 3, e04692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).White MT, Walker P, Karl S, Hetzel MW, Freeman T, Waltmann A, Laman M, Robinson LJ, Ghani A, and Mueller I. (2018) Mathematical modelling of the impact of expanding levels of malaria control interventions on Plasmodium vivax. Nat. Commun. 9, 3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hounkpatin AB, Kreidenweiss A, and Held J. (2019) Clinical utility of tafenoquine in the prevention of relapse of Plasmodium vivax malaria: a review on the mode of action and emerging trial data. Infect. Drug Resist. 12, 553–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Baird JK (2018) Tafenoquine for travelers’ malaria: evidence, rationale and recommendations. Journal of Travel Medicine 25, n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Baird JK (2019) 8-Aminoquinoline Therapy for Latent Malaria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, e00011–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lacerda MVG, Llanos-Cuentas A, Krudsood S, Lon C, Saunders DL, Mohammed R, Yilma D, Batista Pereira D, Espino FEJ, Mia RZ, Chuquiyauri R, Val F, Casapia M, Monteiro WM, Brito MAM, Costa MRF, Buathong N, Noedl H, Diro E, Getie S, Wubie KM, Abdissa A, Zeynudin A, Abebe C, Tada MS, Brand F, Beck HP, Angus B, Duparc S, Kleim JP, Kellam LM, Rousell VM, Jones SW, Hardaker E, Mohamed K, Clover DD, Fletcher K, Breton JJ, Ugwuegbulam CO, Green JA, and Koh G. (2019) Single-Dose Tafenoquine to Prevent Relapse of Plasmodium vivax Malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Llanos-Cuentas A, Lacerda MVG, Hien TT, Velez ID, Namaik-Larp C, Chu CS, Villegas MF, Val F, Monteiro WM, Brito MAM, Costa MRF, Chuquiyauri R, Casapia M, Nguyen CH, Aruachan S, Papwijitsil R, Nosten FH, Bancone G, Angus B, Duparc S, Craig G, Rousell VM, Jones SW, Hardaker E, Clover DD, Kendall L, Mohamed K, Koh G, Wilches VM, Breton JJ, and Green JA (2019) Tafenoquine versus Primaquine to Prevent Relapse of Plasmodium vivax Malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 229–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ashley EA, and Phyo AP (2018) Drugs in Development for Malaria. Drugs 78, 861–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ebstie YA, Abay SM, Tadesse WT, and Ejigu DA (2016) Tafenoquine and its potential in the treatment and relapse prevention of Plasmodium vivax malaria: the evidence to date. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 10, 2387–2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Abreha T, Hwang J, Thriemer K, Tadesse Y, Girma S, Melaku Z, Assef A, Kassa M, Chatfield MD, Landman KZ, Chenet SM, Lucchi NW, Udhayakumar V, Zhou Z, Shi YP, Kachur SP, Jima D, Kebede A, Solomon H, Mekasha A, Alemayehu BH, Malone JL, Dissanayake G, Teka H, Auburn S, von Seidlein L, and Price RN (2017) Comparison of artemether-lumefantrine and chloroquine with and without primaquine for the treatment of Plasmodium vivax infection in Ethiopia: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS medicine 14, No. e1002299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Douglas NM, Poespoprodjo JR, Patriani D, Malloy MJ Kenangalem E, Sugiarto P, Simpson JA, Soenarto Y, Anstey NM, and Price RN (2017) Unsupervised primaquine for the treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria relapses in southern Papua: A hospital-based cohort study. PLoS medicine 14, No. e1002379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Dow G, and Smith B. (2017) The blood schizonticidal activity of tafenoquine makes an essential contribution to its prophylactic efficacy in nonimmune subjects at the intended dose (200 mg). Malar. J. 16, 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Flannery EL, Fidock DA, and Winzeler EA (2013) Using genetic methods to define the targets of compounds with antimalarial activity. J. Med. Chem. 56, 7761–7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Cowell AN, and Winzeler EA (2019) Advances in omics-based methods to identify novel targets for malaria and other parasitic protozoan infections. Genome Med. 11, 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Cowell AN, and Winzeler EA (2019) The genomic architecture of antimalarial drug resistance. Briefings in functional genomics 18, 314–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Mathews ES, and Odom John AR (2018) Tackling resistance: emerging antimalarials and new parasite targets in the era of elimination. F1000Research 7, 1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Goncalves BP, Pett H, Tiono AB, Murry D, Sirima SB, Niemi M, Bousema T, Drakeley C, and Ter Heine R. (2017) Age, Weight, and CYP2D6 Genotype Are Major Determinants of Primaquine Pharmacokinetics in African Children. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e02590–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bennett JW, Pybus BS, Yadava A, Tosh D, Sousa JC, McCarthy WF, Deye G, Melendez V, and Ockenhouse CF (2013) Primaquine failure and cytochrome P-450 2D6 in Plasmodium vivax malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 1381–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Spring MD, Sousa JC, Li Q, Darko CA, Morrison MN, Marcsisin SR, Mills KT, Potter BM, Paolino KM, Twomey PS, Moon JE, Tosh DM, Cicatelli SB, Froude JW, Pybus BS, Oliver TG, McCarthy WF, Waters NC, Smith PL, Reichard GA, and Bennett JW (2019) Determination of Cytochrome P450 Isoenzyme 2D6 (CYP2D6) Genotypes and Pharmacogenomic Impact on Primaquine Metabolism in an Active-Duty US Military Population. J. Infect. Dis. 220, 1761–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Pybus BS, Marcsisin SR, Jin X, Deye G, Sousa JC, Li Q, Caridha D, Zeng Q, Reichard GA, Ockenhouse C, Bennett J, Walker LA, Ohrt C, and Melendez V. (2013) The metabolism of primaquine to its active metabolite is dependent on CYP 2D6. Malar. J. 12, 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Marcsisin SR, Sousa JC, Reichard GA, Caridha D, Zeng Q, Roncal N, McNulty R, Careagabarja J, Sciotti RJ, Bennett JW, Zottig VE, Deye G, Li Q, Read L, Hickman M, Dhammika Nanayakkara NP, Walker LA, Smith B, Melendez V, and Pybus BS (2014) Tafenoquine and NPC-1161B require CYP 2D metabolism for anti-malarial activity: implications for the 8-aminoquinoline class of anti-malarial compounds. Malar. J. 13, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Vuong C, Xie LH, Potter BM, Zhang J, Zhang P, Duan D, Nolan CK, Sciotti RJ, Zottig VE, Nanayakkara NP, Tekwani BL, Walker LA, Smith PL, Paris RM, Read LT, Li Q, Pybus BS, Sousa JC, Reichard GA, Smith B, and Marcsisin SR (2015) Differential cytochrome P450 2D metabolism alters tafenoquine pharmacokinetics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 3864–3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).St Jean PL, Xue Z, Carter N, Koh GC, Duparc S, Taylor M, Beaumont C, Llanos-Cuentas A, Rueangweerayut R, Krudsood S, Green JA, and Rubio JP (2016) Tafenoquine treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria: suggestive evidence that CYP2D6 reduced metabolism is not associated with relapse in the Phase 2b DETECTIVE trial. Malar. J. 15, 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bertschi NL, Voorberg-van der Wel A, Zeeman AM, Schuierer S, Nigsch F, Carbone W, Knehr J, Gupta DK, Hofman SO, van der Werff N, Nieuwenhuis I, Klooster E, Faber BW, Flannery EL, Mikolajczak SA, Chuenchob V, Shrestha B, Beibel M, Bouwmeester T, Kangwanrangsan N, Sattabongkot J, Diagana TT, Kocken CH, and Roma G. (2018) Transcriptomic analysis reveals reduced transcriptional activity in the malaria parasite Plasmodium cynomolgi during progression into dormancy. eLife 7, e41081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Marcsisin SR, Reichard G, and Pybus BS (2016) Primaquine pharmacology in the context of CYP 2D6 pharmacogenomics: Current state of the art. Pharmacol. Ther. 161, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Belorgey D, Antoine Lanfranchi D, and Davioud-Charvet E. (2013) 1,4-naphthoquinones and other NADPH-dependent glutathione reductase-catalyzed redox cyclers as antimalarial agents. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 2512–2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Vasquez-Vivar J, and Augusto O. (1992) Hydroxylated metabolites of the antimalarial drug primaquine. Oxidation and redox cycling. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 6848–6854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Camarda G, Jirawatcharadech P, Priestley RS, Saif A, March S, Wong MHL, Leung S, Miller AB, Baker DA, Alano P, Paine MJI, Bhatia SN, O’Neill PM, Ward SA, and Biagini GA (2019) Antimalarial activity of primaquine operates via a two-step biochemical relay. Nat. Commun. 10, 3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Markus MB (2019) Killing of Plasmodium vivax by Primaquine and Tafenoquine. Trends Parasitol. 35, 857–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Obaldia N, Meibalan E, Sa JM, Ma S, Clark MA, Mejia P, Moraes Barros RR, Otero W, Ferreira MU, Mitchell JR, Milner DA, Huttenhower C, Wirth DF, Duraisingh MT, Wellems TE, and Marti M. (2018) Bone Marrow Is a Major Parasite Reservoir in Plasmodium vivax Infection. mBio 9, e00625–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Saito T, Gutierrez Rico EM, Kikuchi A, Kaneko A, Kumondai M, Akai F, Saigusa D, Oda A, Hirasawa N, and Hiratsuka M. (2018) Functional characterization of 50 CYP2D6 allelic variants by assessing primaquine 5-hydroxylation. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 33, 250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Potter BM, Xie LH, Vuong C, Zhang J, Zhang P, Duan D, Luong TL, Bandara Herath HM, Dhammika Nanayakkara NP, Tekwani BL, Walker LA, Nolan CK, Sciotti RJ, Zottig VE, Smith PL, Paris RM, Read LT, Li Q, Pybus BS, Sousa JC, Reichard GA, and Marcsisin SR (2015) Differential CYP 2D6 metabolism alters primaquine pharmacokinetics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 2380–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Campo B, Vandal O, Wesche DL, and Burrows JN (2015) Killing the hypnozoite–drug discovery approaches to prevent relapse in Plasmodium vivax. Pathog. Global Health 109, 107–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Idowu OR, Peggins JO, Brewer TG, and Kelley C. (1995) Metabolism of a candidate 8-aminoquinoline antimalarial agent, WR 238605, by rat liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 23, 1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Garg A, Prasad B, Takwani H, Jain M, Jain R, and Singh S. (2011) Evidence of the formation of direct covalent adducts of primaquine, 2-tert-butylprimaquine (NP-96) and monohydroxy metabolite of NP-96 with glutathione and N-acetylcysteine. J. Chromatogr. B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 879, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Tilley L, Straimer J, Gnadig NF, Ralph SA, and Fidock DA (2016) Artemisinin Action and Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol. 32, 682–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Paloque L, Ramadani AP, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Augereau JM, and Benoit-Vical F. (2016) Plasmodium falciparum: multifaceted resistance to artemisinins. Malar. J. 15, 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ismail HM, Barton VE, Panchana M, Charoensutthivarakul S, Biagini GA, Ward SA, and O’Neill PM (2016) A Click Chemistry-Based Proteomic Approach Reveals that 1,2,4-Trioxolane and Artemisinin Antimalarials Share a Common Protein Alkylation Profile. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 55, 6401–6405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ismail HM, Barton V, Phanchana M, Charoensutthivarakul S, Wong MH, Hemingway J, Biagini GA, O’Neill PM, and Ward SA (2016) Artemisinin activity-based probes identify multiple molecular targets within the asexual stage of the malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum 3D7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 2080–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Wang J, Zhang CJ, Chia WN, Loh CC, Li Z, Lee YM, He Y, Yuan LX, Lim TK, Liu M, Liew CX, Lee YQ, Zhang J, Lu N, Lim CT, Hua ZC, Liu B, Shen HM, Tan KS, and Lin Q. (2015) Haem-activated promiscuous targeting of artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Commun. 6, 10111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Nouli F., Borlon C, Van Den Abbeele J, D’Alessandro U, and Erhart A. (2013) 1912−2012: a century of research on Plasmodium vivax in vitro culture. Trends Parasitol. 29, 286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Malleret B, Li A, Zhang R, Tan KS, Suwanarusk R, Claser C, Cho JS, Koh EG, Chu CS, Pukrittayakamee S, Ng ML, Ginhoux F, Ng LG, Lim CT, Nosten F, Snounou G, Renia L, and Russell B. (2015) Plasmodium vivax: restricted tropism and rapid remodeling of CD71-positive reticulocytes. Blood 125, 1314–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Chua ACY, Ong JJY, Malleret B, Suwanarusk R, Kosaisavee V, Zeeman AM, Cooper CA, Tan KSW, Zhang R, Tan BH, Abas SN, Yip A, Elliot A, Joyner CJ, Cho JS, Breyer K, Baran S, Lange A, Maher SP, Nosten F, Bodenreider C, Yeung BKS, Mazier D, Galinski MR, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Le Grand R, Kocken CHM, Renia L, Kyle DE, Diagana TT, Snounou G, Russell B, and Bifani P. (2019) Robust continuous in vitro culture of the Plasmodium cynomolgi erythrocytic stages. Nat. Commun. 10, 3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Milner EE, Berman J, Caridha D, Dickson SP, Hickman M, Lee PJ, Marcsisin SR, Read LT, Roncal N, Vesely BA, Xie LH, Zhang J, Zhang P, and Li Q. (2016) Cytochrome P450 2D-mediated metabolism is not necessary for tafenoquine and primaquine to eradicate the erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium berghei. Malar. J. 15, 588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Fasinu PS, Nanayakkara NPD, Wang YH, Chaurasiya ND, Herath HMB, McChesney JD, Avula B, Khan I, Tekwani BL, and Walker LA (2019) Formation primaquine-5,6-orthoquinone, the putative active and toxic metabolite of primaquine via direct oxidation in human erythrocytes. Malar. J. 18, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Carvalho L, Martinez-Garcia M, Perez-Victoria I, Manzano JI, Yardley V, Gamarro F, and Perez-Victoria JM (2015) The Oral Antimalarial Drug Tafenoquine Shows Activity against Trypanosoma brucei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 6151–6160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Carvalho L, Luque-Ortega JR, Manzano JI, Castanys S, Rivas L, and Gamarro F. (2010) Tafenoquine, an antiplasmodial 8-aminoquinoline, targets leishmania respiratory complex III and induces apoptosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 5344–5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Al Mamun Bhuyan A, Bissinger R, Stockinger K, and Lang F. (2016) Stimulation of Suicidal Erythrocyte Death by Tafenoquine. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 39, 2464–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Boulet C, Doerig CD, and Carvalho TG (2018) Manipulating Eryptosis of Human Red Blood Cells: A Novel Antimalarial Strategy? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Wright RO, Lewander WJ, and Woolf AD (1999) Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Annals of emergency medicine 34, 646–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Schuurman M, van Waardenburg D, Da Costa J, Niemarkt H, and Leroy P. (2009) Severe hemolysis and methemoglobinemia following fava beans ingestion in glucose-6-phosphatase dehydrogenase deficiency: case report and literature review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 168, 779–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Khan M, Paul S, Farooq S, Oo TH, Ramshesh P, and Jain N. (2017) Rasburicase-Induced Methemoglobinemia in a Patient with Glucose-6- Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Curr. Drug Saf. 12, 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Ludlow JT, Wilkerson RG, and Nappe TM (2019) Methemoglobinemia. In StatPearls; Treasure Island, FL. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Vasquez-Vivar J, and Augusto O. (1994) Oxidative activity of primaquine metabolites on rat erythrocytes in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Pharmacol. 47, 309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Bowman ZS, Oatis JE Jr., Whelan JL, Jollow DJ, and McMillan DC (2004) Primaquine-induced hemolytic anemia: susceptibility of normal versus glutathione-depleted rat erythrocytes to 5-hydroxyprimaquine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 309, 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Link CM, Theoharides AD, Anders JC, Chung H, and Canfield CJ (1985) Structure-activity relationships of putative primaquine metabolites causing methemoglobin formation in canine hemolysates. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 81, 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Liu H, Ding Y, Walker LA, and Doerksen RJ (2013) Effect of antimalarial drug primaquine and its derivatives on the ionization potential of hemoglobin: A QM/MM study. MedChem-Comm 4, 1145–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Liu H, Walker LA, and Doerksen RJ (2011) DFT study on the radical anions formed by primaquine and its derivatives. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 24, 1476–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Liu H, Walker LA, Nanayakkara NP, and Doerksen RJ (2011) Methemoglobinemia caused by 8-aminoquinoline drugs: DFT calculations suggest an analogy to H4B’s role in nitric oxide synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1172–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Baird K. (2015) Origins and implications of neglect of G6PD deficiency and primaquine toxicity in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Pathog. Global Health 109, 93–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Howes RE, Piel FB, Patil AP, Nyangiri OA, Gething PW, Dewi M, Hogg MM, Battle KE, Padilla CD, Baird JK, and Hay SI (2012) G6PD deficiency prevalence and estimates of affected populations in malaria endemic countries: a geostatistical model-based map. PLoS medicine 9, No. e1001339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Recht J, Ashley EA, and White NJ (2018) Use of primaquine and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency testing: Divergent policies and practices in malaria endemic countries. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 12, No. e0006230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Rueangweerayut R, Bancone G, Harrell EJ, Beelen AP, Kongpatanakul S, Mohrle JJ, Rousell V, Mohamed K, Qureshi A, Narayan S, Yubon N, Miller A, Nosten FH, Luzzatto L, Duparc S, Kleim JP, and Green JA (2017) Hemolytic Potential of Tafenoquine in Female Volunteers Heterozygous for Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) Deficiency (G6PD Mahidol Variant) versus G6PD-Normal Volunteers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97, 702–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Chu CS, Bancone G, Moore KA, Win HH, Thitipanawan N, Po C, Chowwiwat N, Raksapraidee R, Wilairisak P, Phyo AP, Keereecharoen L, Proux S, Charunwatthana P, Nosten F, and White NJ (2017) Haemolysis in G6PD Heterozygous Females Treated with Primaquine for Plasmodium vivax Malaria: A Nested Cohort in a Trial of Radical Curative Regimens. PLoS medicine 14, No. e1002224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Chu CS, and Freedman DO (2019) Tafenoquine and G6PD: a primer for clinicians. Journal of Travel Medicine 26, taz023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Stanton RC (2012) Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, NADPH, and cell survival. IUBMB Life 64, 362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Bradshaw PC (2019) Cytoplasmic and Mitochondrial NADPH-Coupled Redox Systems in the Regulation of Aging. Nutrients 11, 504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Cappellini MD, and Fiorelli G. (2008) Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Lancet 371, 64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Kuhn V, Diederich L, Keller T. C. S. t., Kramer CM, Luckstadt W, Panknin C, Suvorava T, Isakson BE, Kelm M, and Cortese-Krott MM (2017) Red Blood Cell Function and Dysfunction: Redox Regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 26, 718–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Luzzatto L, and Seneca E. (2014) G6PD deficiency: a classic example of pharmacogenetics with on-going clinical implications. Br. J. Haematol. 164, 469–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Beutler E. (2008) Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: a historical perspective. Blood 111, 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Johnson RM, Ravindranath Y, ElAlfy MS, and Goyette G Jr. (1994) Oxidant damage to erythrocyte membrane in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: correlation with in vivo reduced glutathione concentration and membrane protein oxidation. Blood 83, 1117–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Bowman ZS, Morrow JD, Jollow DJ, and McMillan DC (2005) Primaquine-induced hemolytic anemia: role of membrane lipid peroxidation and cytoskeletal protein alterations in the hemotoxicity of 5-hydroxyprimaquine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314, 838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Hopkins J, and Tudhope GR (1974) The effects of drugs on erythrocytes in vitro: Heinz body formation, glutathione peroxidase inhibition and changes in mechanical fragility. British journal of clinical pharmacology 1, 191–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Itano HA, Hirota K, and Vedvick TS (1977) Ligands and oxidants in ferrihemochrome formation and oxidative hemolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74, 2556–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Itano HA, Hosokawa K, and Hirota K. (1976) Induction of haemolytic anaemia by substituted phenylhydrazines. Br. J. Haematol. 32, 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Itano HA, Hirota K, and Hosokawa K. (1975) Mechanism of induction of haemolytic anaemia by phenylhydrazine. Nature 256, 665–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Itano HA (1970) Phenyldiimide, hemoglobin, and Heinz bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 67, 485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Creek DJ, Charman WN, Chiu FC, Prankerd RJ, Dong Y, Vennerstrom JL, and Charman SA (2008) Relationship between antimalarial activity and heme alkylation for spiro- and dispiro-1,2,4-trioxolane antimalarials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 1291–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Robert A, Benoit-Vical F, Claparols C, and Meunier B. (2005) The antimalarial drug artemisinin alkylates heme in infected mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 13676–13680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Carlsson H, Rappaport SM, and Tornqvist M. (2019) Protein Adductomics: Methodologies for Untargeted Screening of Adducts to Serum Albumin and Hemoglobin in Human Blood Samples. High-Throughput 8, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Myint HY, Berman J, Walker L, Pybus B, Melendez V, Baird JK, and Ohrt C. (2011) Review: Improving the therapeutic index of 8-aminoquinolines by the use of drug combinations: review of the literature and proposal for future investigations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 85, 1010–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Dow GS, Gettayacamin M, Hansukjariya P, Imerbsin R, Komcharoen S, Sattabongkot J, Kyle D, Milhous W, Cozens S, Kenworthy D, Miller A, Veazey J, and Ohrt C. (2011) Radical curative efficacy of tafenoquine combination regimens in Plasmodium cynomolgi-infected Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Malar. J. 10, 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Llanos-Cuentas A, Lacerda MV, Rueangweerayut R, Krudsood S, Gupta SK, Kochar SK, Arthur P, Chuenchom N, Mohrle JJ, Duparc S, Ugwuegbulam C, Kleim JP, Carter N, Green JA, and Kellam L. (2014) Tafenoquine plus chloroquine for the treatment and relapse prevention of Plasmodium vivax malaria (DETECTIVE): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 2b dose-selection study. Lancet 383, 1049–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Price RN, von Seidlein L, Valecha N, Nosten F, Baird JK, and White NJ (2014) Global extent of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 982–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Ramharter M, Noedl H, Thimasarn K, Wiedermann G, Wernsdorfer G, and Wernsdorfer WH (2002) In vitro activity of tafenoquine alone and in combination with artemisinin against Plasmodium falciparum. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 67, 39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Kemirembe K, Cabrera M, and Cui L. (2017) Interactions between tafenoquine and artemisinin-combination therapy partner drug in asexual and sexual stage Plasmodium falciparum. Int. J. Parasitol.: Drugs Drug Resist. 7, 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Hwang S, Mruk K, Rahighi S, Raub AG, Chen CH, Dorn LE, Horikoshi N, Wakatsuki S, Chen JK, and Mochly-Rosen D. (2018) Correcting glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency with a small-molecule activator. Nat. Commun. 9, 4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Schmidt LH, Alexander S, Allen L, and Rasco J. (1977) Comparison of the curative antimalarial activities and toxicities of primaquine and its d and l isomers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 12, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Saunders D, Vanachayangkul P, Imerbsin R, Khemawoot P, Siripokasupkul R, Tekwani BL, Sampath A, Nanayakkara NP, Ohrt C, Lanteri C, Gettyacamin M, Teja-Isavadharm P, and Walker L. (2014) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of (+)-primaquine and (−)-primaquine enantiomers in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 7283–7291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Chairat K, Jittamala P, Hanboonkunupakarn B, Pukrittayakamee S, Hanpithakpong W, Blessborn D, White NJ, Day NPJ, and Tarning J. (2018) Enantiospecific pharmacokinetics and drug-drug interactions of primaquine and blood-stage antimalarial drugs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 3102–3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Tekwani BL, Avula B, Sahu R, Chaurasiya ND, Khan SI, Jain S, Fasinu PS, Herath HM, Stanford D, Nanayakkara NP, McChesney JD, Yates TW, ElSohly MA, Khan IA, and Walker LA (2015) Enantioselective pharmacokinetics of primaquine in healthy human volunteers. Drug Metab. Dispos. 43, 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Nanayakkara NP, Ager AL Jr., Bartlett MS, Yardley V, Croft SL, Khan IA, McChesney JD, and Walker LA (2008) Antiparasitic activities and toxicities of individual enantiomers of the 8-aminoquinoline 8-[(4-amino-1-methylbutyl)amino]-6-methoxy-4-methyl-5-[3,4-dichlorophenoxy]quinol ine succinate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 2130–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Davidson DE Jr., Ager AL, Brown JL, Chapple FE, Whitmire RE, and Rossan RN (1981) New tissue schizontocidal antimalarial drugs. Bull. W. H. O. 59, 463–479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Hamerly T, Tweedell RE, Hritzo B, Nyasembe VO, Tekwani BL, Nanayakkara NPD, Walker LA, and Dinglasan RR (2019) NPC1161B, an 8-Aminoquinoline Analog, Is Metabolized in the Mosquito and Inhibits Plasmodium falciparum Oocyst Maturation. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Delves M, Plouffe D, Scheurer C, Meister S, Wittlin S, Winzeler EA, Sinden RE, and Leroy D. (2012) The activities of current antimalarial drugs on the life cycle stages of Plasmodium: a comparative study with human and rodent parasites. PLoS medicine 9, No. e1001169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Rochford R, Ohrt C, Baresel PC, Campo B, Sampath A, Magill AJ, Tekwani BL, and Walker LA (2013) Humanized mouse model of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency for in vivo assessment of hemolytic toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 17486−17491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Vale N, Moreira R, and Gomes P. (2009) Primaquine revisited six decades after its discovery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 44, 937–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Zorc B, Perkovic I, Pavic K, Rajic Z, and Beus M. (2019) Primaquine derivatives: Modifications of the terminal amino group. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 182, 111640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Aguiar AC, Figueiredo FJ, Neuenfeldt PD, Katsuragawa TH, Drawanz BB, Cunico W, Sinnis P, Zavala F, and Krettli AU (2017) Primaquine-thiazolidinones block malaria transmission and development of the liver exoerythrocytic forms. Malar. J. 16, 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Thomson-Luque R, Shaw Saliba K, Kocken CHM, and Pasini EM (2017) A Continuous, Long-Term Plasmodium vivax In Vitro Blood-Stage Culture: What Are We Missing? Trends Parasitol. 33, 921–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Bourgard C, Albrecht L, Kayano A, Sunnerhagen P, and Costa FTM (2018) Plasmodium vivax Biology: Insights Provided by Genomics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Baird JK (2015) Point-of-care G6PD diagnostics for Plasmodium vivax malaria is a clinical and public health urgency. BMC Med. 13, 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Domingo GJ, Satyagraha AW, Anvikar A, Baird K, Bancone G, Bansil P, Carter N, Cheng Q, Culpepper J, Eziefula C, Fukuda M, Green J, Hwang J, Lacerda M, McGray S, Menard D, Nosten F, Nuchprayoon I, Oo NN, Bualombai P, Pumpradit W, Qian K, Recht J, Roca A, Satimai W, Sovannaroth S, Vestergaard LS, and Von Seidlein L. (2013) G6PD testing in support of treatment and elimination of malaria: recommendations for evaluation of G6PD tests. Malar. J. 12, 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Roth A, Mahe SP., Conway A,Ubalee R, Chaumeau V, Andolina C, Kaba SA, Vantaux A, Bakowski MA, Thomson-Luque R, Adapa, Singh, Barnes SJ, Cooper CA, Rouillier M, McNamara CW, Mikolajczak SA, Sather, Witkowski B, Campo B, Kappe SH, Lanar DE, Nosten F, Davidson S, Jiang RHY, Kyle DE, and Adams JH(2018) A comprehensive model for assessment of liver stage therapies targeting Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Commun. 9, 1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (108).Vaughan AM, Kappe SH, Ploss A, and Mikolajczak SA (2012) Development of humanized mouse models to study human malaria parasite infection. Future Microbiol. 7, 657–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (109).Gualdron-Lopez M, Flannery EL, Kangwanrangsan N, Chuenchob V, Fernandez-Orth D, Segui-Barber J, Royo F, Falcon-Perez JM, Fernandez-Becerra C, Lacerda MVG, Kappe SHI, Sattabongkot J, Gonzalez JR, Mikolajczak SA, and Del Portillo HA (2018) Characterization of Plasmodium vivax Proteins in Plasma-Derived Exosomes From Malaria-Infected Liver-Chimeric Humanized Mice. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (110).Foquet L, Schafer C, Minkah NK, Alanine DGW, Flannery EL, Steel RWJ, Sack BK, Camargo N, Fishbaugher M, Betz W, Nguyen T, Billman ZP, Wilson EM, Bial J, Murphy SC, Draper SJ, Mikolajczak SA, and Kappe SHI (2018) Plasmodium falciparum Liver Stage Infection and Transition to Stable Blood Stage Infection in Liver-Humanized and Blood-Humanized FRGN KO Mice Enables Testing of Blood Stage Inhibitory Antibodies (Reticulocyte-Binding Protein Homolog 5) In Vivo. Front. Immunol. 9, 524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (111).Dwyer DJ, Belenky PA, Yang JH, MacDonald IC, Martell JD, Takahashi N, Chan CT, Lobritz MA, Braff D, Schwarz EG, Ye JD, Pati M, Vercruysse M, Ralifo PS, Allison KR, Khalil AS, Ting AY, Walker GC, and Collins JJ (2014) Antibiotics induce redox-related physiological alterations as part of their lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, E2100−2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (112).Kim SY, Park C, Jang HJ, Kim BO, Bae HW, Chung IY, Kim ES, and Cho YH (2019) Antibacterial strategies inspired by the oxidative stress and response networks. J. Microbiol. 57, 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (113).Mordue DG, and Wormser GP (2019) Could the Drug Tafenoquine Revolutionize Treatment of Babesia microti Infection? J. Infect. Dis. 220, 442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (114).Queener SF, Dean RA, Bartlett MS, Milhous WK, Berman JD, Ellis WY, and Smith JW (1992) Efficacy of intermittent dosage of 8-aminoquinolines for therapy or prophylaxis of Pneumocystis pneumonia in rats. J. Infect. Dis. 165, 764–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (115).Radke JB, Burrows JN, Goldberg DE, and Sibley LD (2018) Evaluation of Current and Emerging Antimalarial Medicines for Inhibition of Toxoplasma gondii Growth in Vitro. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 1264–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (116).Kavishe RA, Koenderink JB, and Alifrangis M. (2017) Oxidative stress in malaria and artemisinin combination therapy: Pros and Cons. FEBS J. 284, 2579–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (117).Menard D, and Dondorp A. (2017) Antimalarial Drug Resistance: A Threat to Malaria Elimination. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 7, a025619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (118).Blasco B, Leroy D, and Fidock DA (2017) Antimalarial drug resistance: linking Plasmodium falciparum parasite biology to the clinic. Nat. Med. 23, 917–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (119).Haldar K, Bhattacharjee S, and Safeukui I. (2018) Drug resistance in Plasmodium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 156–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (120).Mok S, Ashley EA, Ferreira PE, Zhu L, Lin Z, Yeo T, Chotivanich K, Imwong M, Pukrittayakamee S, Dhorda M, Nguon C, Lim P, Amaratunga C, Suon S, Hien TT, Htut Y, Faiz MA, Onyamboko MA, Mayxay M, Newton PN, Tripura R, Woodrow CJ, Miotto O, Kwiatkowski DP, Nosten F, Day NP, Preiser PR, White NJ, Dondorp AM, Fairhurst RM, and Bozdech Z. (2015) Drug resistance. Population transcriptomics of human malaria parasites reveals the mechanism of artemisinin resistance. Science 347, 431–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (121).Mok S, Imwong M, Mackinnon MJ, Sim J, Ramadoss R, Yi P, Mayxay M, Chotivanich K, Liong KY, Russell B, Socheat D, Newton PN, Day NP, White NJ, Preiser PR, Nosten F, Dondorp AM, and Bozdech Z. (2011) Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is associated with an altered temporal pattern of transcription. BMC Genomics 12, 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]