Clinical guidelines and consensus statements have traditionally identified achieving clinical remission, defined as a composite outcome based on symptomatic remission and endoscopic healing (based on a Mayo endoscopy subscore [MES] of 0 or 1) as the preferred treatment target in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).1,2 However, approximately 40%–50% of patients with endoscopic healing may have persistent concomitant histologic activity.3 Several recent observational studies and meta-analyses have suggested that patients who achieve deeper levels of remission that include a combination of complete endoscopic remission (MES of 0 or equivalent) and histologic remission may have a substantially lower risk of clinical relapse and disease-related complications than those who achieve conventionally defined remission.4,5 As a result, histologic assessment for remission is gaining traction.

For standardized assessment of histologic activity, several histologic indices have been developed primarily for use in clinical trials, but their uptake in routine clinical practice has been low because they are time consuming and impose significant burden on pathology services.6 To offset this burden, decreased costs and improve point-of-care decision-making and prognostication, virtual chromoendoscopy techniques for optical assessment of colonic mucosa have been developed and iteratively refined over the last decade. In this issue of Gastroenterology, Iaccuci et al7 report the diagnostic and prognostic performance of their virtual chromoendoscopy score, PICaSSO (Paddington International virtual ChromoendoScopy ScOre), in a rigorous, multi-center, transcontinental prospective cohort study.

In this study, 11 trained endoscopists performed tandem high-definition white light and virtual chromoendoscopy in 302 patients with UC, of whom 70% were in conventionally defined endoscopic healing. After initial assessment of MES and the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS), investigators “flipped a switch” on the endoscope, to perform virtual chromoendoscopy and calculated the PICaSSO score based on mucosal architecture (crypt pattern, pattern of microerosions, erosions, and ulcers) and vascular architecture (vascular pattern, vessel dilation, and intramucosal and luminal bleeding). Subsequently, they performed targeted biopsies from the most inflamed region identified by chromoendoscopy, and with central blinded reading calculated histologic activity scores using multiple indices including the Nancy index and the Robarts Histopathology Index. They observed that the PICaSSO scores were more strongly correlated with histologic activity, as compared with MES or UCEIS, although the incremental improvement in accuracy was modest. Importantly, the false-negative rates were lower with PICaSSO than with MES or UCEIS; approximately 94%–97% of patients with PICaSSO-defined endoscopic remission (PICaSSO ≤ 3) were confirmed to be in histologic remission, as compared with only 69%–77% patients with a MES of 0. On longitudinal follow-up over 12 months, patients with endoscopic remission defined based on PICaSSO, MES, or UCEIS, had significantly lower rates of clinical relapse, as compared with patients not in endoscopic remission, confirming prior observations.

Notable strengths of the study are its prospective, multicentric design, blinded histologic assessment using multiple validated indices, and attempts to examine the clinical implications of findings. In addition, before this real-world implementation study, the investigators had comprehensively reported the development and reliability of this score.8 However, there are inherent limitations. The cut-off for PICaSSO-defined endoscopic remission ( ≤ 3) was identified post hoc based on best model fit, and not defined a priori, and hence still requires validation with external cohorts. Longitudinal assessment was limited with a pragmatic definition of relapse, rather than serial structured assessment of patient-reported outcomes and biochemical parameters.

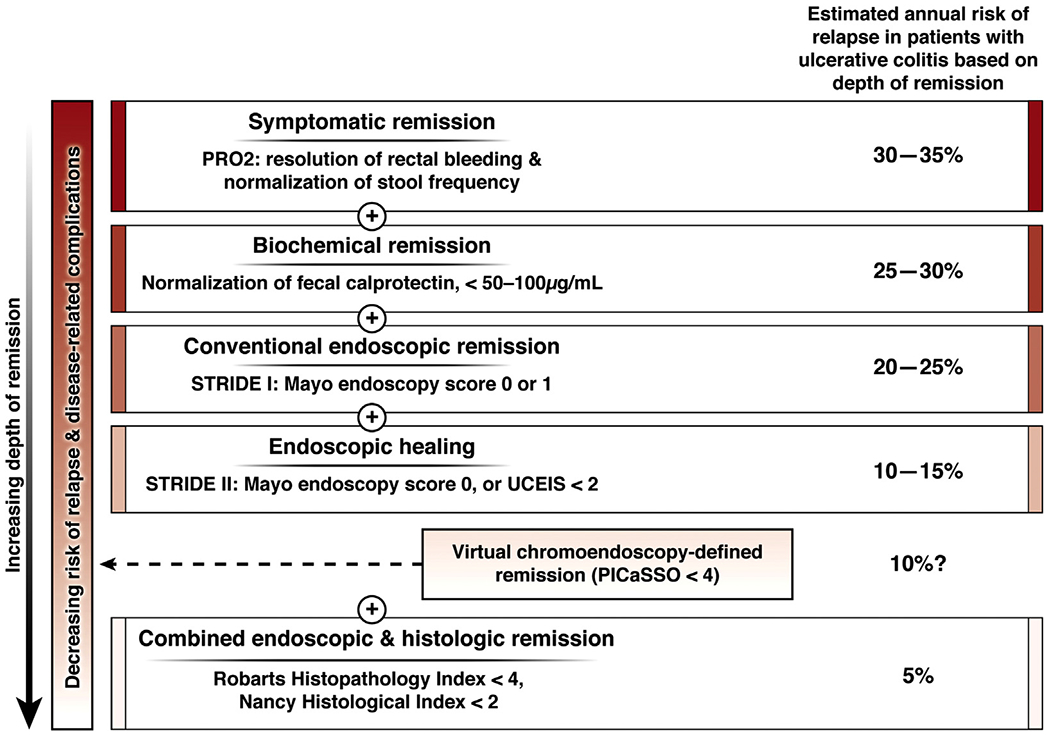

In expert hands, endoscopic remission defined by PICaSSO may represent a deeper form of remission with stronger correlation with histology, as compared with MES or UCEIS. This would help providers to better prognosticate patients’ risk of relapse at the point of care, may conceivably facilitate decision-making regarding treatment de-escalation, and possibly decrease the need for routine histologic assessment. Figure 1 shows the estimated annual risk of relapse in patients with UC based on depth of remission.4

Figure 1.

Depth of remission in ulcerative colitis and corresponding estimated annual risk of relapse.

How likely is this technology to be adopted in routine clinical practice? There are 3 critical determinants of this: (1) What is the incremental benefit of PICaSSO over MES or UCEIS? In this study, although most correlations with histologic activity were statistically stronger with PICaSSO, the clinically meaningful benefit was modest. There was a very strong correlation between PICaSSO, MES, and UCEIS endoscopic scores, and the risk of relapse was comparably low in patients in endoscopic remission defined using PICaSSO, MES, and UCEIS. Although PICaSSO led to lower rates of misclassification of histologic remission as compared with other scores, the downstream impact of medical decision-making of this diagnostic misclassification is expected to be minimal currently. Histologic remission is still not considered a treatment target in UC in the updated STRIDE-II consensus statements, and providers are very unlikely to modify treatment to iteratively achieve histologic remission beyond endoscopic remission in the treat-to-target paradigm.9 (2) How well does PICaSSO perform in a nonexpert’s hands, and how steep is the learning curve? The investigator team has been at the forefront of chromoendoscopy for inflammatory bowel diseases, including dysplasia surveillance and assessment of endoscopic activity. However, the diagnostic performance of virtual chromoendoscopy by nonexperienced gastroenterologists who perform fewer procedures and/or with inadequate training is inferior and time consuming.10 To their credit, the investigators have previously demonstrated very good inter-rater agreement after a computerized module training in nonexpert gastroenterologists.11 However, the motivation of a general gastroenterologist to learn a new technique that offers modest clinical benefit over the widely familiar MES, requires training, and may add more time to an endoscopic examination without corresponding reimbursement, is quite low.12 (3) What competing technologies may be available and what relative advantage could these offer over virtual chromoendoscopy? With rapid advancements in artificial intelligence, deep learning-based image analyses tend to perform vastly better than conventional naked eye endoscopy for assessing disease activity and remission.13 Once this disruptive technique receives regulatory approval, it may be readily available through commercial vendors, be rapidly deployable, and outperform naked eye examinations, thereby rendering current optical diagnoses techniques obsolete.14

In summary, as we strive for more accurate risk stratification and implement treat-to-target strategies, advanced endoscopic techniques for optical enhancement with or without automation, such as virtual chromoendoscopy as described by Iacucci et al, may significantly enhance our decision-making ability in real time. Future studies examining the real-world impact of these technologies on effective and efficient medical decision-making, the ability to reduce healthcare resource utilization, and the impact on long-term patient outcomes are warranted.

See “An international multicenter real-life prospective study of electronic chromoendoscopy score PICaSSO in ulcerative colitis,” by Iacucci M, Smith SC, Bazarova A, et al, on page 000.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

The authors have made the following disclosures: Joseph Meserve: None; Siddharth Singh: Research grants from AbbVie and Janssen.

Funding

Dr Meserve is supported by the NIH/NIDDK T32DK007202. Dr Singh is supported by NIH/NIDDK K23DK117058. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Contributor Information

JOSEPH MESERVE, Division of Gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California.

SIDDHARTH SINGH, Division of Gastroenterology and Division of Biomedical Informatics, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California.

References

- 1.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1324–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:384–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park S, Abdi T, Gentry M, et al. Histological disease activity as a predictor of clinical relapse among patients with ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1692–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon H, Jangi S, Dulai PS, et al. Incremental benefit of achieving endoscopic and histologic remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1262–1275 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta A, Yu A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Treat to target: the role of histologic healing in inflammatory bowel diseases, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020. September 30 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosli MH, Parker CE, Nelson SA, et al. Histologic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 5:CD011256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iacucci M, Smith SC, Bazarova A, et al. An international multicenter real-life prospective study of electronic chromoendoscopy score PICaSSO in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2021;160:00–000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iacucci M, Daperno M, Lazarev M, et al. Development and reliability of the new endoscopic virtual chromoendoscopy score: the PICaSSO (Paddington International Virtual ChromoendoScopy ScOre) in ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;86:1118–1127 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2020. December 21 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Picot J, Rose M, Cooper K, et al. Virtual chromoendoscopy for the real-time assessment of colorectal polyps in vivo: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2017;21:1–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trivedi PJ, Kiesslich R, Hodson J, et al. The Paddington International Virtual Chromoendoscopy Score in ulcerative colitis exhibits very good inter-rater agreement after computerized module training: a multicenter study across academic and community practice (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88:95–106 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langberg KM, Parikh ND, Deng Y, et al. Digital chromoendoscopy utilization in clinical practice: a survey of gastroenterologists in Connecticut. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016;7:268–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takenaka K, Ohtsuka K, Fujii T, et al. Development and validation of a deep neural network for accurate evaluation of endoscopic images from patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;158:2150–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmer AK, Dulai PS. Using artificial intelligence to identify patients with ulcerative colitis in endoscopic and histologic remission. Gastroenterology 2020; 158:2045–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]