Abstract

Nanotechnology and nanoscience are gaining remarkable attention in this era due to their distinctive properties and multi applications. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) is one of the most relevant metal nanoparticles with enormous applications in various field of research and industries. The demand for AuNPs is increasing rapidly. Extensive awareness has been allotted to the development of novel approaches for the synthesis of AuNPs with quality morphological properties using biological sources due to the limitations associated with the chemical and physical methods. Several factors such as contact time, temperature, pH of solution media, concentration of gold precursors and volume of plant extract influences the synthesis, characterization and applications of AuNPs. Characterization of synthesized AuNPs is important in evaluating the morphological properties of AuNPs since the morphological properties of AuNPs affect their potential use in various applications. This review highlights various methods of synthesizing AuNPs, parameters influencing the biosynthesis of AuNPs from plant extract, several techniques used for AuNPs characterization and their potential in bioremediation and biomedical applications.

Keywords: Gold nanoparticles, Synthesis, Plant materials, Bioremediation and pharmacological applications

Gold nanoparticles; Synthesis; Plant materials; Bioremediation and pharmacological applications.

1. Introduction

Metal nanoparticles have displayed enormous potential in various applications due to their exceptional catalytic property, anticancer property, medical diagnostic application, antimicrobial activity, biomedical application, sensory application, food preservation, agriculture, pesticide and insecticide application [1, 2, 3]. AuNPs remain dominant and prominent when compared with other metal nanoparticles due to its activities and applications such as; photothermal therapy, drug delivery, immune chromatographic identification, biosensors, photocatalytic and electronics [4,5] Numerous approaches such as physical, chemical and biological methods have been used in the synthesis of AuNPs [6]. The following advantages of biological methods of AuNPs synthesis; (i) been biologically compatible and offer substantial applications in biology and medical field, (ii) It involve the use of natural substances e.g. algae, plants, fungi, microorganisms, (iii) it does not require the use of toxic regents which enhanced its applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical fields, (iv) it is simple to achieve and consume little energy, (v) it is cost effective because no external stabilizing agents are generally required (vii) the possibility of large-scale synthesis is achievable and (viii) reproducibility is production [7, 8, 9, 10] have made this approach more rewarding when compared with other conventional methods. Plants phytochemicals such as carbohydrates, flavonoids, terpenes, alcohol, phenolics, proteins and glycosides have displayed vast potential in reduction of metal ions from their higher oxidation state to low reduction potential [11, 12, 13]. The antioxidant potential of plant's phytochemicals enhances their rapid conversion of gold precursor (chloroauric acid solution) into AuNPs [14,15]. The extensive applications of AuNPs synthesized using plant extracts in drug delivery, tissue imaging and identification of clinical pathogens are due to their antimicrobial activities which are linked with the plant's phytochemicals found in the extracts [16]. Despite the numerous literatures on synthesis, characterization and applications of AuNPs synthesized using plant extracts, a lot of research is still ongoing in this field owing to the diversity and potential of plants in production of AuNPs with different shapes [10,17, 18, 19]. In this review, we provide a concise introduction to the recent development in green synthesis and characterization techniques involved in AuNPs production. We consequently laid emphasis on the recent advances in the bioremediation and biomedical applications of AuNPs biosynthesized from plant materials.

2. Methods of synthesizing AuNPs

2.1. Physical methods

Evaporation, condensation, high energy ball, milling sputter deposition, pyrolysis, diffusion, laser ablation and plasma arcing are the commonly used techniques associated with the physical methods of synthesizing AuNPs [20]. The use of evaporation-condensation approach for the synthesis of AuNPs involves the use of a tube furnace under atmospheric pressure from which the source material inside a boat centred in the furnace is been vaporized into the carrier gas [21]. Despite the merits of this technique the following are its limitation; large space is needed to accommodate the tube furnace, high amount of energy and time are been wasted in establishing stable thermal condition [22]. The laser ablation is another technique adopted in the physical synthesis of AuNPs, this process occurs in a chamber under vacuum in the presence of inert gases [21]. This approach is advantageous in production of colloidal nanoparticles. Spray pyrolysis, energy ball milling by impact collisions and plasma-arcing in the presence of high temperatures have been used as a physical method for the synthesis of AuNPs [23].

2.2. Chemical method

The most recognized techniques used in the chemical methods of synthesizing AuNPs are chemical reduction, thermal decomposition, electrochemical and micro-emulsion techniques. Chemical reduction involve the use of either inorganic or organic reagents as reducing agents. Reports from literatures have shown trisodium citrate dehydrate, elemental hydrogen sodium borohydride, methoxy polyethylene glycol, ascorbate and potassium bitartrate as prominent reducing agents used in chemical reduction technique [22,24]. Micro-emulsion is another form of the chemical method, it occurs in aqueous cores (nanoreactors) of the reverse micelles which are scattered in an organic reagent and stabilized by surfactant [25]. The micro-emulsion techniques is profitable for the production of AuNPs with control homogeneity, morphological and geometrical properties [26]. The electrochemical method uses electricity as the source of electron for the reduction of gold precursor, the electricity also serves as a controlling force during the synthesis. It demands the passage of electric current into two electrodes separated by electrolyte and the synthesized AuNPs occurs at the electrode or at the electrolyte interface [27]. Thermal decomposition has been documented to be the most common chemical techniques, nucleation occurs during this process when the gold precursor (HAuCl4 or AuCl3) is added into the heated solution in the presence of surfactant and the growth stage happen at a very high reaction temperature [28]. In thermal decomposition process the size of synthesized AuNPs is been determined by reaction temperature, time and surfactant [21]. However, literatures have reported the chemical approaches of AuNPs synthesis using several reducing agents, but some findings revealed that nanoparticles formed from chemical methods show some threats on human health [29].

2.3. Biological methods

Many scientist have utilized the potential of biological materials in development of effective, easy to operate, cheap, less toxic, flexible and environmental friendly route for the synthesis of AuNPs. Biological methods which is also referred to as green synthesis, utilized plant extract [30,31], algae [32], mushrooms [33], bacteria (sulphate-reducing bacteria) [34] and truffles [35] in AuNPs synthesis because they contain biochemicals that function as reducing agent to reduce the cytotoxicity associated with the use of expensive and toxic reagents in chemical method of AuNPs synthesis. The chemical constituents of biological materials such as amine, alkaloids, flavonoids, amides, proteins, tannins, carbohydrates are accountable for the reduction of gold precursor because they contain hydroxyl (–OH) functional groups that can donate electrons to the gold ions. The use of microorganisms in the biosynthesis of AuNPs is very beneficial due to the global availability of enzymes, mycelia and fruiting bodies. Nevertheless, this approach is slow, toxic and the high cost of incubation of some organisms are the limitations of this method [36].

The synthesis of AuNPs using mushroom such as Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus florida [37,38] have been reported. Literature reports have shown the use of algae Turbinaria conoides [39] as reducing agents in AuNPs synthesis. Findings have revealed the synthesis of AuNPs using Fusarium oxysporum [40], Aspergillum sp [41] and Trichoderma viride [42]. Bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumonia, Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeroginosa, Escherichia coli, Rhodopseudomonas capsulate, Streptomyces sp and Staphylococcus epidermidis have been found beneficiary in AuNPs synthesis [43]. List of plant extracts that have been reported for the synthesis of AuNPs are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characterization analysis of some biosynthesized AuNPs using plant sources.

| S/N | Plants name | Plants parts | SPR peak (nm) | Functional group prediction | Techniques for Morphological Assessment | Shape | Size | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alternanthera bettzickiana | Leaf | 520 | 3412 | O–H | EDX, FTIR, TEM, SEM, UV, XRD | Spherical | 60–80 | [78] |

| 2927 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1758 | C=O | ||||||||

| 1454 | C–C | ||||||||

| 1327 | N–O | ||||||||

| 1250 | C–N | ||||||||

| 2 | Musa acuminata colla | Flower | 540 | 3421 | O–H | EDX, UV,XRD, | spherical | 10–16 | [79] |

| 2924 2855 | C–H | ||||||||

| 2357 | C–N | ||||||||

| 1642 | C=O | ||||||||

| 1549 | C–C | ||||||||

| 3 | Flammulina velutipes | Fruit | 563 | 3357 | O–H | FESEM, AFM,UV, DLS, XRD, FTIR | triangular | 74.32 | [49] |

| 2950 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1634 | C–N | ||||||||

| 1389 | C=O | ||||||||

| 4 | Persea americana | Oil | 520 | 3009 | O–H | TEM, XRD, UV,FTIR,DLS | decahedral | 48.8 | [80] |

| 29222853 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1743 | C=O | ||||||||

| 1653 | C=C | ||||||||

| 5 | Galaxaura elongata | - | 500–600 | 3291 | O–H | FTIR,TEM,ZP,UV | Spherical, triangular | 3.85–77.13 | [81] |

| 2158 | C–N | ||||||||

| 1634 | C=C | ||||||||

| 6 | Mentha arvensis | - | 538 | 3450 | O–H | FESEM,UV,FTIR,DLS | spherical | 34 | [82] |

| 1630 | C=O | ||||||||

| 7 | Pelargonium hirsutum | - | 537 | 3500 | O–H | FESEM,UV,FTIR,DLS | spherical | 33.80 | [82] |

| 1624 | C=O | ||||||||

| 8 | Aegle marmelos | Fruit | 519 | 3440–3367 | O–H | UV,TEM,ZP,FTIR, EDX | Spherical | 18 | [83] |

| 2800–3000 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1620–1606 | N–H | ||||||||

| 9 | Eugenia jambolana | Fruit | 523 | 3440–3367 | O–H | UV,TEM,ZP,FTIR, EDX | Spherical | 24 | [83] |

| 2800–3000 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1620–1606 | N–H | ||||||||

| 10 | Annona muricata | Fruit | 526 | 3440–3367 | O–H | UV,TEM,ZP,FTIR,SAED,EDX | Spherical | 16 | [83] |

| 2800–3000 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1620–1606 | N–H | ||||||||

| 11 | Hygrophila spinosa | - | 540 | 3263 | O–H | UV,EDX,TEM, FTIR, XRD,SEM,ZP | Polygonal, rod | 68 | [84] |

| 2926 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1716 | C=O | ||||||||

| 12 | Vitis vinifera | juice | 557 | 975–3650 | O–H | TEM,FTIR,UV | Spherical | 82 | [85] |

| 1503–1687 | C=O | ||||||||

| 13 | Hylocereus undatus | pulp | 560 | 3451 | O–H | TEM,FTIR,UV,XRD | spherical, triangular | 0–20 | [86] |

| 2922 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1640 | C=O | ||||||||

| 14 | Gracilaria verrucosa | Whole plant | 520 | 3448 | O–H | TEM,FTIR,UV,XRD,ZP | Spherical | 20–80 | [87] |

| 2077 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1637 | C=O | ||||||||

| 15 | Mentha piperita | Leaf | 540 | 3399 | N–H | UV,DLS,SEM,FTIR,FESEM | hexagonal | 40–60 | [88] |

| 2135 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1645 | C=O | ||||||||

| 16 | Commiphora wightii | Leaf | 533 | EDX,ERD,TEM,UV,FTIR | Triangular, hexagonal | 20 | [68] | ||

| 17 | Juglans regia | husk | 550 | - | - | XRD,EDX,TEM,FTIR,UV | Spherical | 10–30 | [89] |

| 18 | Dracaena draco | Leaf | 554–532 | 3600–3200 | O–H | UV,FTIR,TEM,EDX,ZP | Spherical | 8–30 | [90] |

| 2900–2800 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1725-1720 | C=O | ||||||||

| 1612 1640 | C=O | ||||||||

| 19 | Justicia adhatoda | Leaf | 537 | - | - | UV,SEM,EDX | Spherical | 13–57 | [47] |

| 20 | Sansevieria roxburghiana | Leaf | 560 | 3415 | N–H.O–H | EDX,XRD,UV,FTIR.TEM,DLS, | spherical | 25 | [91] |

| 1585 | C=C | ||||||||

| 1067 | C–N | ||||||||

| 21 | Allium cepa | Peel | 535 | 3631 | O–H | UV,FESEM,EDX,XRD, FTIR | spherical triangular | 45.42 | [92] |

| 1645 | C=O | ||||||||

| 1321 | C–N | ||||||||

| 22 | Eucommia ulmoides | Bark | 547–536 | 3776 | O–H | EDX,XRD,DLSHRTEM,UV,FTIR | Spherical | 18.2 | [93] |

| 3584 | N–H | ||||||||

| 3116 2910 | C–H | ||||||||

| 1643 | C=O | ||||||||

| 1512 | C=C | ||||||||

| 23 | Muntingia calabura | Fruit | 531 | 3430 | O–H | UV,FTIR,DLS,TEM | spherical and oval | 27 | [94] |

| 2962 | C=O | ||||||||

| 1617 | C=C | ||||||||

| 24 | Agave potatorum | Leaf | 540 | - | - | UV, HTREM,XRD | pseudospherical | 14 | [95] |

| 25 | Mariposa Christia Vespertillonis | Leaf | 550 | - | - | UV,TEM | Irregular | 50–70 | [96] |

| 26 | Zostera noltii | - | 550 | - | - | TEM,EDX | Spherical | 20–35 | [97] |

| 27 | Pleurotus cornucopiae | - | 540 | 3303 | O–H | HRTEM, FTIR, UV, EDX | Spherical | 16–91 | [65] |

| 2121 | C–N | ||||||||

| 1637 | C=O | ||||||||

| 28 | pueraria lobata | 529 | 3529–3232 | O–H | FTIR, UV,TEM,XRD | Spherical | 18 | [66] | |

| 1628 | C=O | ||||||||

Table 2.

Applications of AuNPs synthesized from plants extracts.

| S/N | Plants name | Plants part | Salt/precursor | Applications | Activities | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cistus incanus. | Leaf | HAuCl4 | luminescence properties | The obtained nanoparticles exhibit good multiphoton-excited luminescence properties. | [111] |

| 2 | Alcea rosea | Leaf | HAuCl4 | radical scavenging and catalytic activities | The obtained AuNPs exhibited antioxidant activity against DPPH and ABTS radicals, and catalytic activity in degradation of 4-nitrophenol pollutant | [112] |

| 3 | Punica granatum | Peel | AuCl3 | Water Purification | It exhibit suitable activity for water purification. | [98] |

| 4 | Juglans regia | Bark | HAuCl4 | Cytotoxicity | It enhance the toxicity towards CTX TNA2 cells than free zonisamide. | [113] |

| 5 | Xanthium strumarium L. | Fruit | HAuCl4 | Anti-allergic rhinitis effect | The biosynthesized AuNPs considerably inhibit the allergic inflammation in mice models and could function as anti-allergic rhinitis agents | [114] |

| 6 | Caulerpa racemosa | Whole plant | HAuCl4 | Cytoxicity activities | The synthesized AuNPs effectively inhibit the growth of human colon adenocarcinoma (HT-29) cells, | [115] |

| 7 | Vitis vinifera | Peel | HAuCl4 | cytotoxicity | the cytotoxicity of the gold nanoparticles against skin cancer A431 cell lines | [104] |

| 8 | Eucalyptus globulus | bark | HAuCl4 | Environmental pollution | AuNPs demostrared an eco-friendly reduction conditions | [116] |

| 9 | Citrus limon | - | HAuCl4 | Antibacterial Activity | The Au-NPs showed great potential in inhibiting the activities of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa by damaging their activity | [117] |

| 10 | Croton caudatus Geisel | Leaf | HAuCl4 | Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities | It shows significance Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. |

[118] |

| 11 | Coccinia grandis | Bark | HAuCl4 | cytotoxicity | NAC - Au NPs showed no tocity against fibroblast cells | [119] |

| 12 | Halymenia dilatata | - | HAuCl4 | antioxidant, anti-cancer and antibacterial activities | Hd-AuNPs exhibit commendable antioxidant, anti-cancer and antibacterial activities | [120] |

| 13 | Capsicum annuum | Pulp | HAuCl4 | Catalytic activity. | The GNPs synthesized showed potential catalytic activity. | [121] |

| 14 |

Ruellia tuberosa, Phyllanthus acidus |

Leaves, wing | HAuCl4 | enzyme activity | It enhanced the enzyme activity on α-amylase, cellulase, and xylanase | [122] |

| 15 | Cassytha filiformis | Leaf | HAuCl3.H2O | biodegradation | It shows promising photocatalytic degradation of cationic dye | [123] |

| 16 | Alpinia nigra | Leaf | HAuCl3.H2O | biodegradation | The synthesized AuNPs in the presence of sunlight catalyzed the degradation of the Methyl Orange and Rhodamine B with percent degradation of 83.25% and 87.64% respectively | [124] |

DPPH = 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate, ABTS = 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), HAuCl4 = gold(iii)chloride hydrate, HAuCl4 = Chloroauric acid.

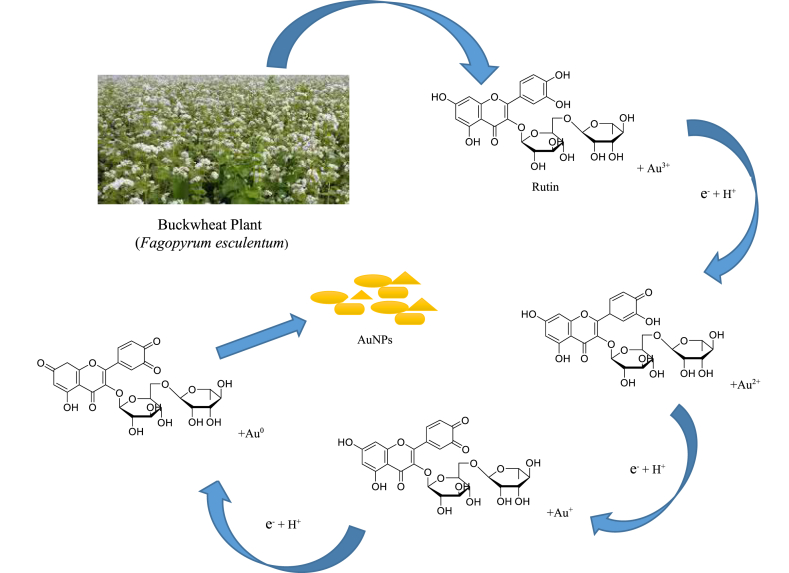

Mechanism for the synthesis of AuNPs using plant extracts

The importance of plant extracts in the synthesis of AuNPs was presented in the reaction mechanism given in Figure 1. The reduction of gold salt to gold nanoparticles (Au3+→Au0) using plant extract was possible due to the presence of some phytochemicals found in the plant's extract as illustrated with equation I-III. Such phytochemicals have the potential of donating the needed electrons for the relative conversion of (Au3+→Au0). The presence of hydroxyl functional groups in plant extract enhanced the interaction of –OH with Au3+ ions to form gold complexes which can be reduced to a stable Au0 [44].

| Au3+ + e− → Au2+ | (1) |

| Au2+ + e− → Au+ | (2) |

| Au+ + e− → Au0+ | (3) |

Figure 1.

Mechanism of AuNPs synthesis using Plant extracts.

3. Characterization of nanoparticles

The main parameters studied when AuNPs are characterized are surface charge, crystallinity, morphology and particle size. The various techniques used for the evaluation and quantification of these parameters are summarized in detail below.

3.1. Nanoparticle formation analysis

UV-visible spectroscopic analysis is used to ascertain the formation of AuNPs by measuring the surface plasmon resonance [SPR] and assessing the collective oscillations of conduction bands of electrons generated by electromagnetic waves [45]. The use of UV-visible spectroscopic analysis have aided the determination of some morphological features such as stability, size, structure and shape of AuNPs [46]. Each metal nanoparticles has a precise absorbance band in representative spectra when incident light encounter some resonance with the conduction band electrons on the surface of the nanoparticles. Due to the excitation mode of the surface plasmons, AuNPs have an absorbance peak in the range of 500–550 nm [47]. The shift in the SPR peak towards the blue shift (lower frequency) had been reported to indicate decrease in size of AuNPs size whereas the red shift (lower frequency) signifies an increase in AuNPs size. The red shift occurs when the crystal size grows after nucleation and the distance between valence band increases [48]. Comprehensive information on the use of UV-visible spectroscopy in the confirmation of AuNPs formation is described in Table 1.

3.2. Functional group determination

Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) is used for the determination of the functional groups that induced the reduction of metal precursors [49]. To achieve this, the technique measures the absorption of electromagnetic radiation in the infrared region of wavelengths (4000-600 cm-1). FTIR spectrum describes the location of bands in relation to the nature of bonds and definite functional groups [49]. The peaks at the following wavelength specify functional groups associated with AuNPs synthesis. 3400-3380 for Ν-Η amines, 3570-3200 for O–H of alcohols, 3130-3070 cm−1 for aromatic C–H, 2970-2860 cm−1 for Methyl C–H, 2300-2150 cm−1 for C–N of nitriles, 1790-1690 for carbonyl –C=O, 1680-1620 cm−1 for C=C alkenes and 1470-1370 cm−1 for Methyl C–H as showed in Table 1. Phytochemicals with the listed functional groups are expected to be capable of reducing gold precursor because they are capable of donating electrons needed for the reduction of gold ions to a lower oxidation state [50]. Comprehensive information from previous literatures on the use of FTIR as characterization technique in green synthesis of AuNPs are presented in Table 1.

3.3. Morphology and particle size determination

The effective applications of AuNPs depend largely on their morphological properties and particle size distribution. Hence the need for the evaluation of these feacture via characterization are very significant. The following microscopy techniques; transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning electron microscope (SEM) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) are mostly used to measure the aforementioned properties [51].

3.3.1. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM/HRTEM)

TEM is a commonly used techniques for the determination of shape, morphology and size of AuNPs. This technique is based on the interaction between a thin sample and a uniform current density electron beam (energies in the range of 150 to 60 keV). When the electron beam come in contact with the sample, most of the electrons are transmitted, while the rest are scattered. Data generated from the transmitted electrons are used for the production of the TEM image [52]. The degree of such interaction depends on size, elemental composition and sample density. TEM is rampantly used for size and shape analysis. TEM does not only offers direct images of nanoparticles it equally gives an accurate estimation of their homogeneity [52,53]. Nevertheless, common limitations of TEM technique are; it damage samples that cannot withstand the vacuum pressure of the microscope, it produce misleading images as a result of orientation effects, sample preparation is difficult, it waste time because the samples must be ultrathin for electron transmittance and it cannot be used for the quantification of large number of particles [52,54]. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) is another version of TEM which allows the combination of both the transmitted and scattered electrons for the production of its image because it make use of phase-contrast imaging [55]. This technique offer more benefits when compared with TEM it generating high resolution images and can also characterize the internal structure of nanoparticles [56]. Detailed findings on the use of TEM and HRTEM in the determination of size, shape and morphology of AuNPs is presented in Table 1.

3.3.2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM is another microscopic technique that enhances the morphological characterization of nanoparticles through direct visualization [57]. When AuNPs are exposed to electron beams they generate signals that are recorded by the detector which gives information about the chemical composition, external morphology, orientation and crystalline structure of AuNPs [58]. It exhibit several benefits such as prevention of sample destruction, it permit visualization of morphological properties in liquid state which prevent destruction of polymeric nanoparticles because complete drying could alter their morphological identities. Despite these advantages the following are its demerits; it doesn't offer accurate information about the true population average and size distribution, it is time wasting, costly to operate and it damage samples that cannot withstand vacuum pressure [52]. The applications of this technique in determination of the size and shape of AuNPs are listed in Table 1.

3.3.3. Atomic force microscopy

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) are used for identification of the morphological identities of nanoparticles. The difference between this technique and SEM/TEM is the production of three-dimensional images which enable the evaluation of the particle volume and height [59]. This technique is based on the physical scanning of nanoparticles at submicron level via a probe tip [60]. With the aid of AFM, the size (length, width, and height), surface texture and morphology of nanoparticles can be determined with software based image processing [61]. This technique has ability to produce images of nanoparticles without any further treatment [62]. Reports on the morphological characterization of AuNPs via AFM are presented in Table 1.

3.4. Dynamic light scattering

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) is a popular technique used for estimating particle size distribution. DLS has been reported to be a good technique for the measurement of Brownian nanoparticles sizes in colloidal suspensions [63]. DLS make use of diffusion coefficient in the computation of size distribution and nanoparticles motion [64]. Reports on the application of DLS in size distribution of AuNPs are stated in Table 1.

3.5. Elemental composition

Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectra (EDX) had been reported by several researchers to be a good technique for the estimation of elemental compositions and purity determination in AuNPs synthesis [65]. This is achieved from the quantification of X-rays emissions from nanoparticles after they are bombarded by electron beam [46]. EDX detector are connected to SEM for the detection of number of X-rays emitted so as to balance the difference in energy of two electrons. The energy generated by the emitted X-ray is a characteristic property of the element, which when qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed gives the composition of the element present in the synthesized AuNPs [66].

3.6. Crystallinity analysis

The crystallinity of nanoparticles is determine via X-ray Diffraction (XRD) technique [67]. This technique measures the diffraction angle obtained from the structure and lattice parameters of the diffracted powder samples when X-ray beam incident on them. The particle sizes are then estimated according to the width of the X-ray peaks via the Scherrer formula in equation iv [68].

| D = kλ / β cos2θ | (4) |

where D represent the average thickness of crystalline grains at the crystal plane (n), K denote the Scherrer constant (0.89), β stand for the Full-Width Half Maximum, θ represent diffraction angle and λ signify X-ray wavelength (0.15418 nm).

3.7. Raman spectroscopy/surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)

SERS technique incorporates nanotechnology into normal Raman spectroscopy. The normal Raman technique depends on the inelastic scattering irradiated analyte produced by laser. Therefore, any polarizable sample under laser irradiation will be detected by Raman spectroscopy [69]. SERS was design to solve some problems associated with Raman spectroscopy such as difficulty in determination of samples at low concentrations and poor fluorescence interference. SERS has been reported to display a remarkable advantages of rapid identification of NPs from their dissolved ions and bulk counterparts over other techniques [69]. SERS has been successfully used for the size determination of some nanoparticles [70]. The use of SERS imaging in intracellular and extracellular mapping of AuNPs synthesized using green algae Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata has been documented [71] Lahr et al. reported that SERS is useful in tracking AuNPs fate in microfluidic paper-based analytical devices [72]. AuNPs toxicity against microorganisms had been estimated with the use of SERS [73]. The adsorption of molecules onto AuNPs surfaces had been monitored via SERS [74].

3.8. Zeta potential

Zeta Potential (ZP) is a prominent analytical tool used for the determination of surface charge of AuNPs in colloidal solution. The surface of a charged nanoparticles attracts a tiny layer of oppositely charge ions and binds firmly to form a thin liquid layer. The diffusion of the particles through the solution involve an outer diffuse layer which consists of roughly associated ions thereby forming an electrical double layer [75]. ZP values are used in predicting the stability of nanoparticles and the values ranges from +100 to -100 mV. AuNPs with ZP values greater than +25 mV or lesser than –25 mV are regarded as been stable. Lower ZP values are associated with aggregation or coagulation as a result of van der Waals attraction [76]. The ZP values in the range of -33.59 to -29.1 mV has been reported for AuNPs synthesized using Leucosidea sericea [77].

4. Applications of AuNPs synthesized from plant extracts

4.1. Catalytic application

The aquatic ecosystem are polluted when municipal and industrial effluent are discharged into them, this happening had cause enormous environmental and health menaces. Several techniques such as osmotic pressure, adsorption and coagulation have been utilized in treating the effects of wastes and effluents from the aquatic ecosystem but each techniques have some unique merits and demerits. Interestingly, the photocatalytic treatment using biosynthesized AuNPs from plant sources provides a cost effective and environmental friendly approach of solving this problem [98]. The effective use of AuNPs as photocatalytic agent in degradation of organic pollutants are linked to their large surface area or the quantum confinement effects [99]. The catalytic efficiency of AuNPs biosynthesized from Mimosa tenuiflora extract has been stated [100]. Also the investigation of biosynthesized AuNPs using Trichoderma sp as catalytic agent in degradation of azo dyes has been established [101]. Furthermore, AuNPs Phyto-synthesized from Delonix regia leaf extract demonstrated potential catalytic activity [102]. More relevant information on the catalytic application of AuNPs mediated from plant extracts are presented in Table 2.

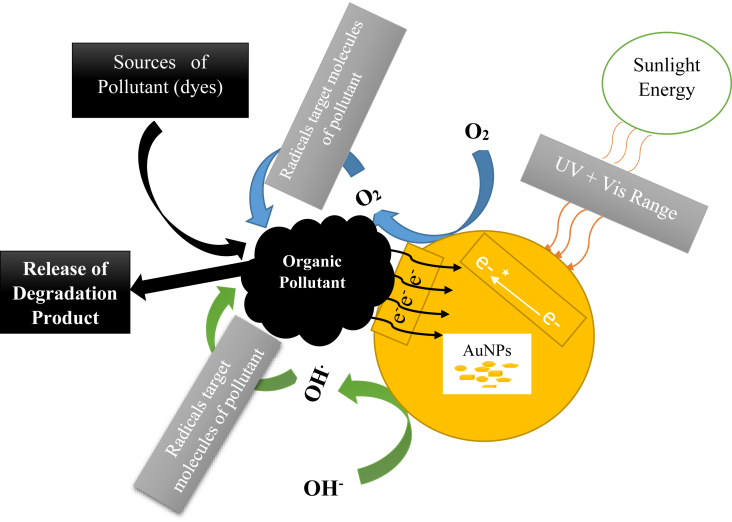

Possible catalytic mechanism

Two mechanisms have been proposed for the photocatalytic efficiency of AuNPs; Firstly, AuNPs are capable of inducing localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) by absorption of visible light with equivalent wavelengths of their plasmonic absorption bands. The electromagnetic field associated with LSPR can enhance the production and separation of electron/hole pairs in the semiconductor. Secondly, AuNPs can serve as electron sinks to attract photogenerated electrons, thereby causing an effectual separation of electron/hole pairs. However, the aforementioned mechanisms depend on the AuNPs sizes, larger-sized AuNPs follows the LSPR effects whereas smaller-sized AuNPs generally behaves as electron sinks [28]. The schematic representation of the degradation mechanism of AuNPs is showed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of degradation of some dyes using the AuNPs.

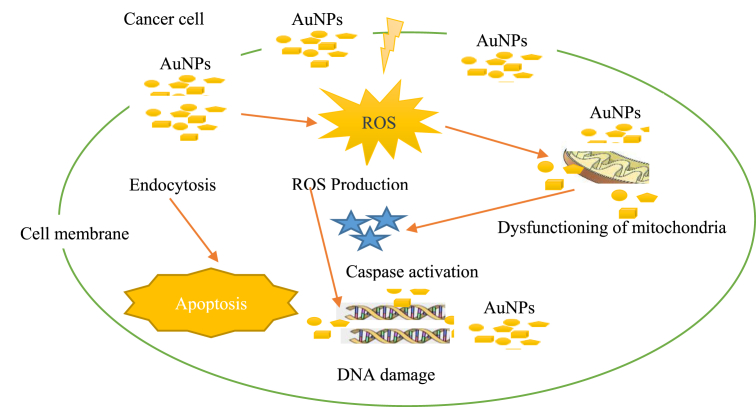

4.2. Anticancer application

Biosynthesized AuNPs are found to possess distinctive anticancer activities, because biomolecules can easily absorb to their surfaces making it superior to other materials in inhibiting the growth of cancer cell [103]. AuNPs produced using plants were reported to have huge anticancer potential since they demonstrated toxic activity against cancer cells [104]. The efficacy of AuNPs produced using Vitis vinifera peel showed commendable biocompatibility towards normal human cell line and selective toxicity against skin cancer A431 cell lines rendering it a good anticancer agent [105]. The cytotoxic investigation of AuNPs against the growth of human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) showed 60% cell death at concentrations of 120 mg/ml. It was also observed that the cytotoxicity increased with the increase in concentration of AuNPs [83]. Findings had shown that the anticancer efficiency of AuNPs depends on the stabilizing agent and size [106]. Other useful information on the anticancer application of green synthesized AuNPs are showed in Table 2. The Schematic representation of the anticancer activity of AuNPs is showed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the anticancer activity of AuNPs.

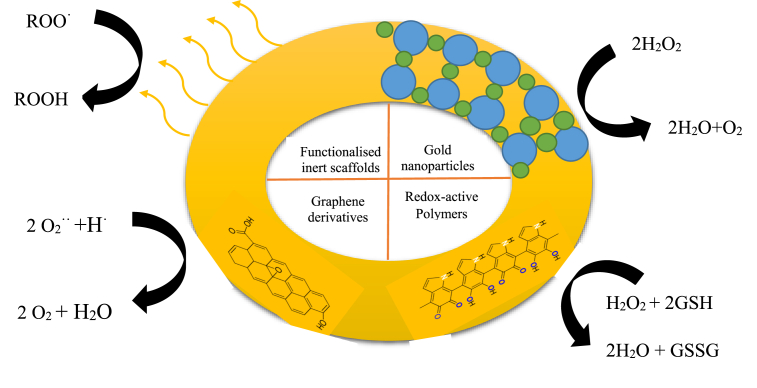

4.3. Antioxidant application

The results obtained from 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate (DPPH) assay of AuNPs mediated from Alium cepa displayed moderate antioxidant activity of 14.44% at 100 μg/ml while the reference standard showed scavenging activity of 36.54% at same concentrations when compared [92]. The DPPH scavenging potential of phytosynthesized AuNPs are linked to the presence of secondary metabolites in plant extracts [107]. The antioxidant analysis of AuNPs prepared from avocado oil showed an antioxidant efficiency of 30.49 % at 40 μL. The antioxidant efficiency was ascribed to the functionalization of AuNPs with some organic constituents derived from the avocado oil [80]. Reports from previous studies have claimed that the interaction of AuNPs with free radicals are influenced by some factors such as specific surface, concentration and size. Furthermore, the authors equally stated that larger size AuNPs exhibits lower antioxidant potency when compared with smaller size of AuNPs [80,84]. Relevant information on the antioxidant efficiency of AuNPs synthesized using plant extracts are presented in Table 2. The Schematic representation of the antioxidant activity of AuNPs is showed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the antioxidant activity of AuNPs.

4.4. Antimicrobial application

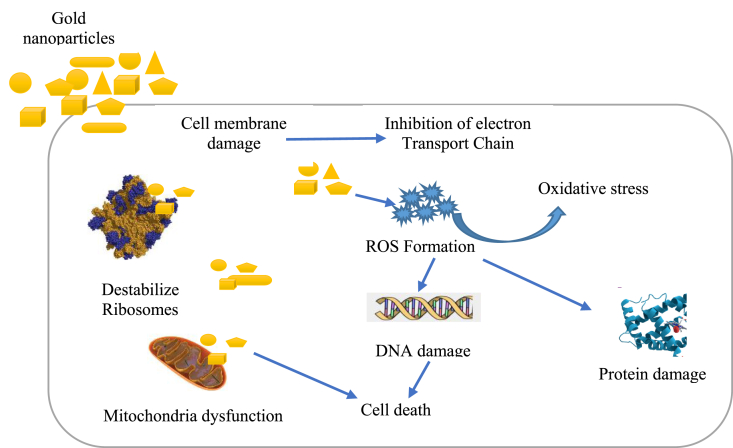

AuNPs synthesized from the powder of Galaxaura elongata was found to be an effective antibacterial agents judging from the inhibition zones of 13.5 and 13 mm demonstrated against the growth of E. coli and K. pneumoniae respectively [81]. The proteomic study of AuNPs against the growth of E. coli cells showed an alterations in the expression of heat sock protein even at short exposure [108]. Green synthesis of AuNPs using Alternanthera bettzickiana leaf extract demonstrated a significant antibacterial effect rendering it a promising antibacterial agent. Interestingly, report had shown that biosynthesized AuNPs displayed more efficient antibacterial activity than chemically synthesized AuNPs when compared, such antibacterial potency may be due to the synergistic effect of the plant extracts [78]. Several finding have shown that AuNPs synthesized from plant extracts exhibit remarkable antimicrobial activities against several microbes [109,110]. Additional findings on the antimicrobial application of phytosynthesized AuNPs are showed in Table 2. The Schematic representation of the antibacterial mechanism of AuNPs is showed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the antibacterial mechanism of AuNPs.

5. The challenges and future of AuNPs for bioremediation and biomedical applications

The applications of AuNPs is on a widespread across the globe as its usefulness in most life fields such as dye, electronics, textile, food, medicine and other industries are increasing on daily basis [125]. Recently nanoscience and nanotechnology are providing remarkable and promising bioremediation and biomedical applications than what is recorded in previous decades. The quest to search for a lasting solution to improve human health status through disease diagnosis and production of novel medicine had made Nano research a very relevant field of study [126]. This move will continue to grow rapidly with provision of prominent contributions to public health and other fields [127]. However, the safety level of AuNPs in bioremediation and biomedical applications are becoming worrisome and its raising some future challenges due to nanotoxicity because the interaction of AuNPs with biological systems are govern by several factors such as cell type, uptake routes or directing different organelles which might sometimes be harmful [128]. Also investigation of the mechanism of interaction, degradation and bioaccumulation of metal nanoparticles in living organism had revealed that the physico-chemical properties (particle sizes and shapes) of nanoparticles influences their toxicological behaviors greatly [129]. Surface modification and dosage regulation of nanoparticles had been documented as appropriate route to enhance nanoparticles efficiency, safety and could also cause the reduction of their negative impacts [130]. Scaling-up the synthesis of AuNPs from laboratory approach to meet the commercial demand is also a great challenge to bioremediation and biomedical researchers because particles size control and modification are easier at the laboratory scale due to nanoparticles composition when compared with industrial scale [131]. A comprehensive understanding of the reaction mechanisms, intracellular mechanisms, dosage, route trafficking and biological activity of AuNPs are highly required to proceed in this facet.

6. Conclusion

Considering the various methods of synthesizing AuNPs, the phytosynthesis based method is regarded as the best, due to its invincible benefits in terms of cost effectiveness, possibility of been scale up for large scale production, reproducibility, environmental-friendly, immunological behavior, easy operation, tunability and relative abundance of plants. In this review, the green synthesis and various techniques used for characterization of phytosynthesized AuNPs were properly described in detail. The tremendous potential of phytosynthsized AuNPs in bioremediation and biomedical applications were comprehensively highlighted. These remarkable potentials are attributed to the functional groups found in plant extracts and morphological identities of AuNPs. Future studies on green synthesis of AuNPs should focus on providing more relevant information on factors influencing its synthesis, durable mode of preservation of extracts for longer period, more sophisticated and easy to operate techniques for characterization of AuNPs so as to enhance the wide applications of phytosynthesized AuNPs in more field of sciences and technologies.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge (Prof. O.M Olabemiwo and Prof. O.S Bello) of the Department of Pure and Applied Chemistry Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso Nigeria for their immense support during this review. Also, the authors would like to appreciate the Chinese Scholarship Council of the People Republic of China for their support.

Contributor Information

Sunday Adewale Akintelu, Email: akintelusundayadewale@gmail.com.

Aderonke Similoluwa Folorunso, Email: folorunsoaderonkesimi@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Duhan J.S., Kumar R., Kumar N., Kaur P., Nehra K., Duhan S. Nanotechnology: the new perspective in precision agriculture. Biotech. Rep. 2017;15:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akintelu S.A., Folorunso A.S., Ademosun O.T. Instrumental characterization and antibacterial investigation of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Garcinia kola leaf. J. Drug Deliv. Therapeut. 2019;9:58–64. (6-s) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akintelu S.A., Folorunso A.S. Biosynthesis, characterization and antifungal investigation of Ag-Cu nanoparticles from bark extracts of Garcina kola. Stem Cell. 2019;10(4):30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang X., El-Sayed M.A. Gold nanoparticles: optical properties and implementations in cancer diagnosis and photothermal therapy. J. Adv. Res. 2010;1:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narayanan K.B., Sakthivel N. Phytosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using leaf extract of Coleus amboinicus Lour. Mater. Char. 2010;61:1232–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folorunso A., Akintelu S., Oyebamiji A.K., Ajayi S., Abiola B., Abdusalam I., Morakinyo A. Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial Activity of gold nanoparticles from leaf extracts of Annona muricata. J. Nanostru. Chem. 2019;9(2):111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senthilkumar S., Kashinath L., Ashok M., Rajendran A. Antibacterial properties and mechanism of gold nanoparticles obtained from pergularia daemia leaf extract. J. Nano Res. 2017;6(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinay S.P., Udayabhanu, Nagaraju G. Biomedical applications of Durio zibethinus extract mediated gold nanoparticles as antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticoagulant activity. Int. J. Biosen. Bioelectron. 2019;5(5):150–155. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudhane A.A., Waghmode S.R., Dama L.B., Mhaindarkar V.P., Sonawane A., Katariya S. Synthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticles using plant extract of Terminalia arjuna with antibacterial activity. Int. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019;2(15):75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis S., Koshy E., Mathew B. Microwave aided synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and their antioxidant, antimicrobial and catalytic potentials. J. Nanostruct. 2018;8(1):55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akintelu S.A., Folorunso A.S., Folorunso F.A., K Oyebamiji A. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for biomedical application and environmental remediation. Hel. 2020;6:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04508. e04508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francisa S., Koshya E.P., Mathew B. Microwave aided and plant reduced gold nanoparticles as talented dye degradation catalysts. Sci. Iran. F. 2019;26(3):1944–1950. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rautray S., Rajananthini A.S. Therapeutic potential of green, Synthesized Gold Nanoparticles. BioPharm. Int. 2020:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markus J., Wang D., Kim Y.J., Ahn S., Mathiyalagan R., Wang C., Yang D.C. Biosynthesis, characterization, and bioactivities evaluation of silver and gold nanoparticles mediated by the roots of Chinese herbal Angelica pubescens Maxim. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017;12 doi: 10.1186/s11671-017-1833-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akintelu S.A., Olugbeko S.C., Folorunso A.S. A review on synthesis, optimization, characterization and antibacterial application of gold nanoparticles synthesized from plants. Int. Nano Lett. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akintelu S.A., Yao B., Folorunso A.S. A review on synthesis, optimization, mechanism, characterization, and antibacterial application of silver nanoparticles synthesized from plants. J. Chem. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubey S.P., Lahtinen M., Sarkka H., Sillanpaa M. Bioprospective of Sorbus aucuparia leaf extract in development of silver and gold nanocolloids. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2010;80:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vijaya K.P., Jelastin K.S., Prakash K.S. Synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Xanthium strumarium leaves extract and their antimicrobial studies: a green approach. Rasayan J. Chem. 2018;11(4):1544–1551. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huu D., Derek F., Gerrard E.J.P. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles from waste macadamia nut shells and their antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus epidermis. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2019;7(4):1171–1177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shankar P.D., Shobana S., Karuppusamy I., Pugazhendhi A., Ramkumar V.A., Arvindnarayan S., Kumar G. A review on the biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles (gold and silver) using bio-components of microalgae: formation mechanism and applications. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijayaraghavan K., Ashokkumar T. Plant-mediated biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles: a review of literature, factors affecting synthesis, characterization techniques and applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santhoshkumar J., Rajeshkumar S., Venkat Kumar S. Phyto-assisted synthesis, characterization and applications of gold nanoparticles – a review. Biochem. Biophy. Rept. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chellapandian C., Ramkumar B., Puja P., Shanmuganathan R., Pugazhendhi A., Kumar P. Gold nanoparticles using red seaweed Gracilaria verrucosa: green synthesis, characterization and biocompatibility studies. Process Biochem. 2019;80:58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan Y., Dai Y., Li Y., Zhua D. Preparation of gold, platinum, palladium and silver nanoparticles by the reduction of their salts with a weak reductant-potassium bitartrate. J. Mater. Chem. 2003;13:1069–1075. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganguli A.K., Ahmad T., Vaidya S., Ahmed J. Microemulsion route to the synthesis of nanoparticles. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008;80:2451–2477. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malik M.A., Wani M.Y., Hashim M.A. Microemulsion method: a novel route to synthesize organic and inorganic nanomaterials: 1st Nano Update. Arabian J. Chem. 2012;5:397–417. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma H., Yin B., Wang S., Jiao Y., Pan W., Huang S., Chen S., Meng F. Synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles by a novel electrochemical method. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2004;24:68–75. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinay S.P., Udayabhanu, Nagaraju G., Chandrappa C.P., Chandrasekhar N. Hydrothermal synthesis of gold nanoparticles using spider cobweb as novel biomaterial: application to photocatalytic. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akintelu S.A., Folorunso A.S. A review on green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using plant extracts and its biomedical applications. BioNanoSci. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akintelu S.A., Folorunso A.S. Characterization and antimicrobial investigation of synthesized silver nanoparticles from Annona muricata leaf extracts. J. Nanotech. Nanomed. Nanobiotech. 2019;6:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akintelu S.A., Folorunso A.S., Oyebamiji A.K., Erazua E.A. Antibacterial potency of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Boerhaavia diffusa leaf extract as reductive and stabilizing agent. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019;10(12):374–380. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noelia G.B., C Rodríguez-Argüelles M., Prado-López S., Lastra M., Grimaldi M., Cavazza A., Nasi L., Salviati G., Bigi F. Msc; 2018. Macroalgae to Nanoparticles: Study of Ulva Lactuca L. Role in Biosynthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles and of Their Cytotoxicity on colon Cancer Cell Lines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owaid M.N. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Pleurotus (oyster mushroom) and their bioactivity : Review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2019;12:100256. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Assunção A., Vieira B., Lourenço J.P., Costa M.C. Recovery of gold (0) nanoparticles from aqueous solutions using effluents from a bioremediation process”. RSC Adv. 2016;6(114):112784–112794. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owaid M.N., Muslim R.F., Hamad H.A. Mycosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Terminia sp. desert truffle, pezizaceae, and their antibacterial activity. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2018;11:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owaid M.N., Ibraheem I.J. Mycosynthesis of nanoparticles using edible and medicinal mushrooms. Eur. J. Nanomed. 2017;9:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eskandari-Nojedehi M., Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H., Rahbar-Shahrouzi J. Hydrothermal green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) extract: physico-chemical characteristics and antifungal activity studies. Green Process. Synth. 2018;7:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhat R., Sharanabasava V.G., Deshpande R., Shetti U., Sanjeev G., Venkataraman A. Photo-bio-synthesis of irregular shaped functionalized gold nanoparticles using edible mushroom Pleurotus florida and its anticancer evaluation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2013;125:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rajeshkumar S., Malarkodi C., Gnanajobitha G., Paulkumar K., Vanaja M., Kannan C., Annadurai G. Seaweed-mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Turbinaria conoides and its characterization. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2013;3:44. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukherjee P., Senapati S., Mandal D., Ahmad A., Khan M.I., Kumar R., Sastry M. Extracellular synthesis of gold nanoparticles by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Chem. Bio. Chem. 2002;3:461–463. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020503)3:5<461::AID-CBIC461>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuanyuan Q., Xiaofang P., Wenli S., Xuwang Z., Jingwei W., Zhaojing Z., Shuzhen L., Shengnan Y., Fang M., Jiti Z. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by Aspergillum sp. WL-Au for degradation of aromatic pollutants. Phys. E Low-dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mishra A., Kumari M., Pandey S., Chaudhry V., Gupta K.C., Nautiyal C.S. Biocatalytic and antimicrobial activities of gold nanoparticles synthesized by Trichoderma sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2014;166:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srinath B.S., Ravishankar R.V. Rapid biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by staphylococcus epidermidis: its characterization and catalytic activity. Mater. Lett. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akintelu A.S., Yao B., Folorunso A.S. Green synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial investigation of synthesized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) from Garcinia kola pulp extract. Plasmonics. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ingale A.G., Chaudhari A.N. Biogenic synthesis of nanoparticles and potential applications: an eco-friendly approach. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2013;(4):2. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jayanta K.P., Kwang-Hyun B. Green nanobiotechnology: factors affecting synthesis and characterization techniques. J. Nanomater. 2014:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Latha D., Sampurnam S., Arulvasu C., Prabu P., Govindaraju K., Narayanan V. Biosynthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticle from Justicia adhatoda and its catalytic activity Materials. Today Off. Proc. 2018;5:8968–8972. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Virendra N.R., Arvind K., Srivastava, Chandrachud M., Sudip K.D. Surface enhanced absorption and transmission from dye coated gold nanoparticles in thin films. Appl. Opt. 2012;51:2606–2615. doi: 10.1364/AO.51.002606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rabeea M.A., Owaid M.N., Aziz A.A., Jameel M.S., Dheyab M.A. Mycosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using the extract of Flammulina velutipes, Physalacriaceae, and their efficacy for decolorization of methylene blue. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdul W.W., Abdul K., Smawati A., Wayan I.S. Bio-synthesis of gold nanoparticles through bioreduction using the aqueous extract of Muntingia calabura L. Leaves orient. J. Chem. 2018;34(1):401–409. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pal S.L., Jana U., Manna P.K., Mohanta G.P., Manavalan R. Nanoparticle: an overview of preparation and characterization. J. App. Pharm. Sci. 2011;1(6):228–234. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mourdikoudis S., Pallares R.M., Pallares R.M., Thanh N.T.K. 2018. Characterization Techniques for Nanoparticles: Comparison and Complementarity upon Studying Nanoparticle Properties Nanoscale; pp. 1–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamini S.Y., Vinay V.K., Bodaiah B., Pavani B.B., Sudhakar P. Green synthesis of Silver and Gold nanoparticles using Shorea tumbuggaia bark extract and screening for their Catalytic activity. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. Mgt. 2019;4(2):180–185. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anuradha J., Abbasi T., Abbasi S. Green’synthesis of gold nanoparticles with aqueous extracts of neem (Azadirachta indica) Res. J. Biotechnol. 2010;5(1):75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ismail M.I.M. Green synthesis and characterizations of copper nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaur P., Thakur R., Chaudhury A. Biogenesis of copper nanoparticles using peel extract of Punica granatum and their antimicrobial activity against opportunistic pathogens. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2016;9:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Linga-Rao M., Savithramma N. Biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Svensonia Hyderabadensis leaf extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial efficacy. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Res. 2011;3(3):1117–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Devi N.N., Shankar P.D., Femina W., Paramasivam T. Antimicrobial efficacy of green synthesized silver nanoparticles from the medicinal plant Plectranthus amboinicus. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Rev. Res. 2012;12(1):164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Folorunso F.A., Folorunso A.S., Akintelu S.A. Investigation of the effectiveness of biosynthesised gold nanoparticle from Garcinia kola leaves against fungal infections’. Int. J. Nanopart. 2020;12(4):316–326. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akintelu S.A., Olugbeko S.C., Folorunso F.A., Oyebamiji A.K., Folorunso A.S. Characterization and pharmacological efficacy of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using the bark extract of Garcinia kola. J. Chem. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nargund Chidanandappa V.B. Green synthesis of chitosan based copper nanoparticles and their bio-efficacy against bacterial blight of pomegranate (Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. punicae) Int. J. Curr.Microbiol. App. Sci. 2020;9(1):1298–1305. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shende S., Ingle A.P., Gade A., Rai M. Green synthesis of copper nanoparticles by Citrus medica Linn. (Idilimbu) juice and its antimicrobial activity. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;31:865–873. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1840-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muhammad R., Ahson J.S., Reena R., Muhammad B.T., B Hafiz F., Muhammad S.H., Faiz R. A review on synthesis, characterization and applications of copper nanoparticles. Using green method. Nano. Brief Rept. Rev. 2017;4(12):1750043–1750066. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saxena A., Tripathi R.M., Singh R.P. Biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles by using onion (Allium cepa) extract and their antibacterial activity. Dig. J. Nanomat. Biostruc. 2010;2(5):427–432. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mustafa N.O., Sajid S.S.A., Idham A.A. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using yellow oyster mushroom Pleurotus cornucopiae var. citrinopileatus. Environ. Nanotechn. Mon. Mgt. 2017;8:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qixin Z., Meishuang Z., Qiongxia L., Ran W., Yunzhi F., Tifeng J. Facile biosynthesis and grown mechanism of gold nanoparticles in pueraria lobata extract. Colloids Surf. A. 2019;567:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mata R., Bhaskaran A., Sadras S.R. Green-synthesized gold nanoparticles from plumeria alba flower extract to augment catalytic degradation of organic dyes and inhibit bacterial growth. Particuology. 2016;24:78–86. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uzma M., Sunayana N., Raghavendra V.B., Madhu C.S., Shanmuganathan R., Brindhadevi K. Biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Commiphora wightii and their cytotoxic effects on breast cancer cell line (MCF-7), Pro. Biochem. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huiyuan G., Lili H., Baoshan X. Applications of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy in the analysis of nanoparticles in the environment”. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2017;4:2093–2107. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barbara A., Dubois F., Ibanez A., Eng L.M., Quémerais P. SERS correlation spectroscopy of silver aggregates in colloidal suspension: quantitative sizing down to a single nanoparticle. J. Phys. Chem. 2012;118:17922–17931. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lahr R.H., Vikesland J.P. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) cellular imaging of intracellulary biosynthesized gold nanoparticles. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014;2(7):159–160. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lahr R.H., Wallace G.C., Vikesland P.J. Raman characterization of nanoparticle. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:9139–9146. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b01192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yuan Z., Li J., Cui L., Xu B., Zhang H., Yu C.P. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with pure nitrifying bacteria. Chemosphere. 2013;90(4):1404–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Winuprasith T., Suphantharika M., McClements D.J., He L. Spectroscopic studies of conformational changes of β-lactoglobulin adsorbed on gold nanoparticle surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;416:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clogston J.D., Patri A.K. Zeta potential measurement. In: McNeil S., editor. Characterization of Nanoparticles Intended for Drug Delivery. Humana Press; 2011. pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Horie M., Fujita K. Toxicity of metal oxides nanoparticles. Adv. Mol. Toxicol. 2011:145–178. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Umar M.B., Enas I., Adewale O.A., Subelia B., Jelili A.B., Jeanine L.M., Christopher N.C., Ahmed A.H. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles capped with procyanidins from Leucosidea sericea as potential antidiabetic and antioxidant agents. Biomol. 2020;10(3):452. doi: 10.3390/biom10030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nagalingama M., Kalpanab V.N., Devi Rajeswarib V., Panneerselvama A. Biosynthesis, characterization, and evaluation of bioactivities of leaf extract-mediated biocompatible gold nanoparticles from Alternanthera bettzickiana. Biotechnol. Rep. 2018;19 doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2018.e00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Valsalam S., Agastian P., Esmail G.A. Biosynthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles using Musa acuminata colla flower and its pharmaceutical activity against bacteria and anticancer efficacy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kumar B., Smita K., Debut A., Cumbal L. Utilization of Persea americana (Avocado) oil for the synthesis of gold nanoparticles in sunlight and evaluation of antioxidant and photocatalytic activities. Environ. Nanotech. Mon. Mgt. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Neveen A., Nouf M.A., Ibraheem B.M.I. Green biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Galaxaura elongata and characterization of their antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2017;10:3029–3039. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jafarizad A., Safaee K., Gharibian S., Omidi Y., Ekinci D. Biosynthesis and in-vitro study of gold nanoparticles using mentha and Pelargonium extracts. Procedia Mat. Sci. 2015;11:224–230. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vijayakumar S. Eco-friendly synthesis of gold nanoparticles using fruit extracts and in vitro anticancer studies. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2019;23:753–761. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Satpathy S., Patra A., Ahirwar B., Hussain M.D. Process optimization for green synthesis of gold nanoparticles mediated by extract of Hygrophila spinosa T. Anders and their biological applications. Phys. E Low-dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dzimitrowicz A., Jamroz P., diCenzo G.C., Gil W., Bojszczak W., Motyka A., Pogoda D., Pohl P. Fermented juices as reducing and capping agents for the biosynthesis of size-defined spherical gold nanoparticles. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Divakaran D., Lakkakula J.R., Thakur M., Kumar Kumawat M., Srivastava R. Dragon fruit extract capped gold nanoparticles: synthesis and their differential cytotoxicity effect on breast cancer cells. Mater. Lett. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chellamuthu C., Balakrishnan R., Patel P., Rajasree S., Arivalagan P., Ponnuchamy K. Gold nanoparticles using red seaweed Gracilaria verrucosa: green synthesis, characterization and biocompatibility studies. Process Biochem. 2019;80:58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nabeel A., Sharad B., Ritika S., Danish I., Ghosh A.K., Rajiv D. Biosynthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticles: kinetics, in vitro and in vivo study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2017;78:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Izadiyan Z., Shameli K., Hara H., Mohd Taib S.H. Cytotoxicity assay of biosynthesis gold nanoparticles mediated by walnut (Juglans regia) green husk extract. J. Mol. Strt. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Manuel L., Rafael Z., María J.M., Almoraima G., Laura M.C., Juan J.D., José M.P., Valme G., Yolanda C. Biosynthesis of uniform ultra-small gold nanoparticles by aged Dracaena Draco L extracts. Col. Surf. SA. 2019;581:123744. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Indramani K., Moumita M., Vadivel M., Natarajan S. Green one-pot synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Sansevieria roxburghiana leaf extract for the catalytic degradation of toxic organic pollutants. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019;117:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Patra J.K., Kwon Y., Baek K. Green biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by onion peel extract: synthesis, characterization and biological activities. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mingxia G., Wei L., Feng Y., Huihong L. Controllable biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles from a Eucommia ulmoides bark aqueous extract. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015;142:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.01.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kumar P.S., Jeyalatha M.V., Malathi J., Ignacimuthu S. Anticancer effects of one-pot synthesized biogenic gold nanoparticles (Mc-AuNps) against laryngeal carcinoma. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moreno-Luna F.B., Tovar-Corona A., Herrera-Perez J.L., Santoyo-Salazar J., Rubio- Rosas E., Vázquez-Cuchillo O. Quick synthesis of gold nanoparticles at low temperature, by using Agave potatorum extracts. Mater. Lett. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mohamed S.O., Nur A.A.B., Nurulhuda A., Syahmi I.K., Amirul I.D.S., A Mohd A.M., Najmiddin Y. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using aqueous extracts of Mariposa Cristia Vespertillonis: influence of pH on its colloidal Stability. Mater. Today: SAVE Proc. 2018;5:22050–22055. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rafael Z., Manuel J., María L.A., María J.O., José M.P., Ignacio N., Juan J.D., Laura M.C. Analytical determination of the reducing and stabilization agents present in different Zostera noltii extracts used for the biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles. J. Photobio. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pawan K., Rajesh T., Himanshu M., Anju M., Ashok C. Biosynthesis of biocompatible and recyclable silver/iron and gold/iron core-shell nanoparticles for water purification technology. Biocat. Agri. Biotechnol. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mohite P., Apte M., Kumar A.R., Zinjarde S. Biogenic nanoparticles from Schwanniomyces occidentalis NCIM 3459: mechanistic aspects and catalytic applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016;179:583–596. doi: 10.1007/s12010-016-2015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rodríguez-León E., Rodríguez-Vázquez B.E., Martínez-Higuera A., Rodríguez- Beas C., Larios-Rodríguez E., Navarro R.E., López-Esparza R., Iñiguez- Palomares R.A. Synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Mimosa tenuiflora extract, assessments of cytotoxicity , cellular uptake , and catalysis. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019:334. doi: 10.1186/s11671-019-3158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Qu Y., Shen W., Pei X., Ma F., You S., Li S., Wang J., Zhou J. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by Trichoderma sp. WL-Go for azo dyes decolorization. J. Environ. Sci. 2017;56:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dauthal P., Mukhopadhyay M. Phyto-synthesis and structural characterization of catalytically active gold nanoparticles biosynthesized using Delonix regia leaf extract. Biotech. 2016;3:6. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0432-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ahmad N., Bhatnagar S., Saxena R., Iqbal D., Ghosh A.K., Dutta R. Biosynthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticles: kinetics, in vitro and in vivo study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2017;78:553–556. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.González-Ballesteros N., Prado-López S., Rodríguez-González J.B., Lastra M., Rodríguez-Argüelles M.C. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using brown algae Cystoseira baccata: its activity in colon cancer cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointer. 2017;153:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Grace Nirmala J., Akila S., Narendhirakannan R.T., Chatterjee S. Vitis vinifera peel polyphenols stabilized gold nanoparticles induce cytotoxicity and apoptotic cell death in A431 skin cancer cell lines. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 106.Koperuncholan M. Bioreduction of chloroauric acid (HAuCl4) for the synthesis of gold nanoparticles (GNPs): a special empathies of pharmacological activity. Int. J. Phytopharm. 2015;5(4):72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Brown A.N., Smith K., Samuels T.A., Lu J.R., Obare S.O., Scott M.E. Nanoparticles functionalized with ampicillin destroy multiple-antibiotic-resistant isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter aerogenes and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:2768–2774. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06513-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Eom S.H., Kim Y.M., Kim S.K. Antimicrobial effect of phlorotannina from marine brown algae. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;50:3251–3255. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.MubarakAli D., Thajuddin N., Jeganathan K., Gunasekaran M. Plant extract mediated synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and its antibacterial activity against clinically isolated pathogens. Colloids Surf. B. 2011;85(2):360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Eskandari-Nojehdehi M., Jafarizadeh-Malmiri H., Rahbar-Shahrouzi J. Optimization of processing parameters in green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using microwave and edible mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) extract and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016;5:537–548. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Magdalena K., Katarzyna B., Joanna O., Marek S. Popcorn-shaped gold nanoparticles: plant extract-mediated synthesis, characterization and multiphoton-excited luminescence properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019;229:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Khoshnamvand M., Ashtiani S., Huo C., Saeb S.P., Liu J. Use of Alcea rosea leaf extract for biomimetic synthesis of gold nanoparticles with innate free radical scavenging and catalytic activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chunyang F., Ziping M., Liqiu C., Hongjie L., Chao J., Wenbin Z. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles, characterization and their loading with zonisamide as a novel drug delivery system for the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. J. Photobio. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Qianhua P., RuiXiang C. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Caffeoylxanthiazonoside, chemical isolated from Xanthium strumarium L. fruit and their Anti-allergic rhinitis effect- a traditional Chinese medicine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019;192:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Muthushanmugam M., Subramanian P., Manoharan V., Baskaran K., Sonaimuthu M., Manikandan R., Tabarsa M., You S., Marimuthu P.N. Facile green route synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Caulerpa racemosa for biomedical applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ricardo J.B.P., L José M.F., Madalena P.M., Sónia A.O.S., Armando J.D.S., Paula A.A.P., Carmen S.R.F. Demystifying the morphology and size control on the biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Eucalyptus globulus bark extract. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2017;105:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hadeel S.M., Biosynthesis P. Azra. Characterization and antibacterial activity of gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) using black lemon extract. Mater. Today: SAVE Proc. 2019;18:5164–5169. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Vijaya Kumar P., Mary Jelastin Kala S., Prakash K.S. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Croton Caudatus Geisel Leaf extract and their biological studies. Mater. Lett. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yan W., Ruichun X., Hao H., Tao P. Biosynthesis, characterization and cytotoxicity of gold nanoparticles and their loading with N-acetylcarnosine for cataract treatment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018;187:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Manoharan V., Subramanian P., Ramasamy M., Samayanan S., Ethiraj K., SangGuan Y., Narayanasamy M.P. Biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles from Halymenia dilatata for pharmaceutical applications: antioxidant, anti-cancer and antibacterial activities. Process Biochem. 2019;85:219–229. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chun-Gang Y., Can H., Shuixin Y., Bing G. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Capsicum annuum var. grossum pulp extract and its catalytic activity. Phys. E Low-dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 122.Vasantharaj S., Sripriya N., Shanmugavel M., Manikandan E., Gnanamani A., Senthilkumar P. Surface active gold nanoparticles biosynthesis by new approach for bionanocatalytic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. Bio. 2018;179:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.S Rohit K., Saroj S.B., Khushboo R.S., Sourav M., Bijayananda P., Tapas R.S., Panka K.P., Dindyal M. Biosynthesized gold nanoparticles as photocatalysts for selective degradation of cationic dye and their antimicrobial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 124.Debjani B., Monmi G., Raj N.S., Archana Y., Archana M.D. Biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their application in photocatalytic degradation of toxic dyes. JPB. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Elkodousa M.A., El-Sayyadb G.S., Abdelrahmanc I.Y., El-Bastawisy H.S., Mohamedd A.E., Mosallamb F.M., Nassere H.A., Gobara M., Baraka A., Elsayed M.A., El-Batal A.I. Therapeutic and diagnostic potential of nanomaterials for enhanced biomedical applications. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2019;180:411–428. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Elahi N., Kamali M., Baghersad M.H.J.T. Recent biomedical applications of gold nanoparticles: a review. Talanta. 2018;184:537–556. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Azar A.T. Technology, Biomedical Engineering: specialisations and future challenges. Int. J. Bio. Eng. 2011;6:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Amin Y.M., Hawas A.M., El-Batal A., Elsayed S.H.H.E. Evaluation of acute and subchronic toxicity of silver nanoparticles in normal and irradiated animals. Br. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015;6:22–38. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ajdary M., Moosavi M., Rahmati M., Falahati M., Mahboubi M., Mandegary A., Jangjoo S., Mohammadinejad R., Varma R.J.N. Health concerns of various nanoparticles: a review of their in vitro and in vivo toxicity. Nanomat. 2018;8:634. doi: 10.3390/nano8090634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Choi A.O., Cho S.J., Desbarats J., Lovrić J., Maysinger D.J.Jon. Quantum dotinduced cell death involves Fas upregulation and lipid peroxidation in human neuroblastoma cells. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2007;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Colombo S., Beck-Broichsitter M., Botker J.P., Malmsten M., Rantanen J., Bohr A.J. Addr. Transforming nanomedicine manufacturing toward Quality by Design and microfluidics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018;128:115–131. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.