Abstract

Ancient pottery from the Nyanga agricultural complex (CE 1300–1900) in north-eastern Zimbabwe enjoys more than a century of archaeological research. Though several studies dedicated to the pottery have expanded the frontiers of knowledge about the peopling of Bantu-speaking agropastoral societies in this part of southern Africa, we know little about the social context in which the pottery was made, distributed, used, and discarded in everyday life. This mostly comes from the fact that the majority of the ceramic studies undertaken were rooted in Eurocentric typological approaches to material culture hence these processes were elided by most researchers. As part of the decolonial turn in African archaeology geared at rethinking our current understanding of the everyday life of precolonial agropastoral societies, we explored the lifecycle of traditional pottery among the Manyika, one of the local communities historically connected to the Nyanga archaeological landscape. The study proffered new dimensions to the previous typological analyses. It revealed a range of everyday roles and cultural contexts that probably shaped the lifecycle of local pottery in ancient Nyanga.

Keywords: Nyanga pottery, African-centred knowledge, Decolonised archaeology, Iron Age, Manyika, Material culture

Nyanga pottery, African-centred knowledge, Decolonised archaeology, Iron age, Manyika, Material culture.

1. Introduction

For more than a century, archaeologists working in the Nyanga1 agricultural complex have recovered thousands of broken potsherds and few complete earthenware vessels left by agropastoral societies that resided in eastern Zimbabwe during the later Iron Age (Randall-MacIver, 1906; Mason, 1933; Fripp and Wells, 1938; Summers, 1958; Brand, 1970; Manyanga, 1995; Soper and Chirawu, 1997; Soper, 2002; Manyanga and Shenjere, 2012). Whereas typological analysis of the pottery based on the character and variability of the stylistic and decoration attributes has played a pivotal role towards expanding the frontiers of knowledge about the culture-history of this landscape in precolonial southern Zambezia, little is known about the social context in which the pottery was made, exchanged, and used in everyday life. This mostly comes from the fact that the majority of these studies were undertaken using Eurocentric approaches to material culture (i.e. Randall-MacIver, 1906; Martin, 1937; Fripp and Wells, 1938; Schofield, 1948; Summers, 1958; Brand, 1970; Manyanga, 1995; Soper and Chirawu, 1997; Soper, 2002; Manyanga and Shenjere, 2012) that maginalised most of these aspects. This is particularly important to explore if one considers the dearth of such research in southern African Iron Age studies where pottery is generally examined to establish groups identities and their relative chronologies as if it was not active in everyday life (Beach, 1980; Hall, 1983; Ndoro, 1996; Pikirayi, 1999; Mtetwa et al., 2013; Nyamushosho, 2014; Nyamushosho and Chirikure, 2020). Yes, stylistic typologies are vital, but what about the social processes that entangled the pots with the individuals who manufactured or used them in their everyday life? Typology has become more important than other issues which remain obscured only because they are better researched archaeologically. Given that typology is the lifeblood of Iron Age studies in southern Africa, where do we go from here? Regardless, this is not to suggest a farewell to ceramic typology analyses. For so long African-centred knowledge has been ignored in addressing this problem, yet it could be one way to usher us beyond this obvious dead-end (Ndoro, 1996; Pikirayi, 1999; Pikirayi and Lindahl, 2013; Chirikure, 2016, Chirikure, 2020). This paper is part of our recent efforts to reconfigure pottery studies of ancient Nyanga in a new direction. It explores the social lifecycle of Manyika pottery from modern-day Nyanga, right from production to discard to develop an emic perspective of the relations that possibly existed between the Later Iron Age (CE 1300–1900) communities of Nyanga and the various broken potsherds and few complete earthenware archaeologists recovered from their upland and lowland residences (sensu [19941998], [19941999]; David and Kramer, 2001; Hodder and Hutson, 2003; Stark, 2003; Fowler, 2008; Pikirayi, 2007; Skibo, 1992, 2013 Ashley, 2010). This approach is in liaison with decolonial studies trending in global archaeology and ethnoarchaeology, where archaeologists and anthropologists now recognise the significance of locally-centred knowledges when approaching material culture (Dietler and Herbich, 1989; Collett, 1993; Lindahl and Matenga, 1995; Ndoro, 1996; Gosselain, 2000; 2016; Ogundele, 2006; Pikirayi, 2007; 2015; Karega-Munene and Schmidt, 2010; Lindahl and Pikirayi, 2010; Lane, 2011; Mtetwa et al., 2013; Nyamushosho, 2014; Chirikure, 2016, Chirikure, 2020; Haber, 2016; Cunningham and MacEachern, 2016; Chirikure et al., 2018; Chipangura et al., 2019). In light of this, we approach decolonised archaeology as a philosophical and archaeological practice that is independent of colonial prejudices and hegemonic discourses; hence studying and portraying past societies in a more engaging way that resonates with local meanings and contexts of their material culture (Stahl, 1995; Stark, 2003; Pikirayi, 2015; Cunningham and MacEachern, 2016; Haber, 2016; Chirikure et al., 2017). What we attempt here is not to throw the baby out with the bathwater or create a new academy that wipes off colonial wisdom, but decentring Eurocentrism which seeks to universalise archaeological meanings, and processes. Thus, our study builds on recent contributions which attempt to augment the current understanding of the everyday life of the Later Iron Age societies of ancient Nyanga using local epistemologies, ontologies, and practices (i.e. Mupira, 2001; Chirikure and Rehren, 2004; Murimbika, 2006; Shenjere, 2011; Nyamushosho, 2013, 2017; Pasipanodya et al., 2016; Chipangura, 2020; Nyamushosho and Chirikure, 2020). Nevertheless, the focus this time is on archaeological pottery which was recovered from the modern-day Manyika territory.

2. A brief background to the Nyanga agricultural complex and the Manyika

The Nyanga agricultural complex is one of the unique Iron Age landscapes in southern Africa that portrays a colossal footprint of intensified agricultural systems of Bantu agropastoral societies that thrived between CE 1300 and 1900 (Pikirayi, 2001; Soper, 2002; Mitchell, 2004; Philipson, 2005; Mupira, 2013). Geographically the complex is bordered by Nyangombe River to the north and Zonwe River to the south (Figure 1). The majority of previous archaeological investigations (e.g. Randall-MacIver, 1906; Mason, 1933; Martin, 1937; Summers, 1958; Sutton, 1984; Soper, 2002) concentrated on the north-eastern edge of the complex; however, recent studies uncovered architectural and ceramic evidence which extended the boundaries of the complex further north and south as far as Avila Mission (Shenjere, 2011) and the Vumba Mountains (Katsamudanga, 2007) respectively.

Figure 1.

The Nyanga complex showing the distribution of some archaeological sites situated in the Manyika territory. Source: Authors own.

The recreated culture-historical sequence which is based on pottery style, decoration attributes, and radiocarbon data recognises the makers of Bambata ware (CE 150–650) as the earliest inhabitants of Nyanga, followed by the makers of Ziwa ware (CE 300–1000) and lastly those of Nyanga ware (see Mason, 1933; Martin, 1937; Schofield, 1948; Summers, 1958; Manyanga, 1995; Soper, 2002; Manyanga and Shenjere, 2012; Huffman, 2007). The later ware is associated with the terrace-building community that occupied the agricultural complex between the 14th and the 20th centuries (Soper, 2002). Nyanga ware mainly comprises necked pots with out-turning lips, hemispherical bowls with open lips, open bowls with out-sloping lips, and large-mouthed pots with out-turning lips (see Figure 2). These were occasionally decorated with raised ribs and cross-hatched incisions (Mason, 1933; Summers, 1958; Manyanga, 1995; Soper, 2002; Manyanga and Shenjere, 2012).

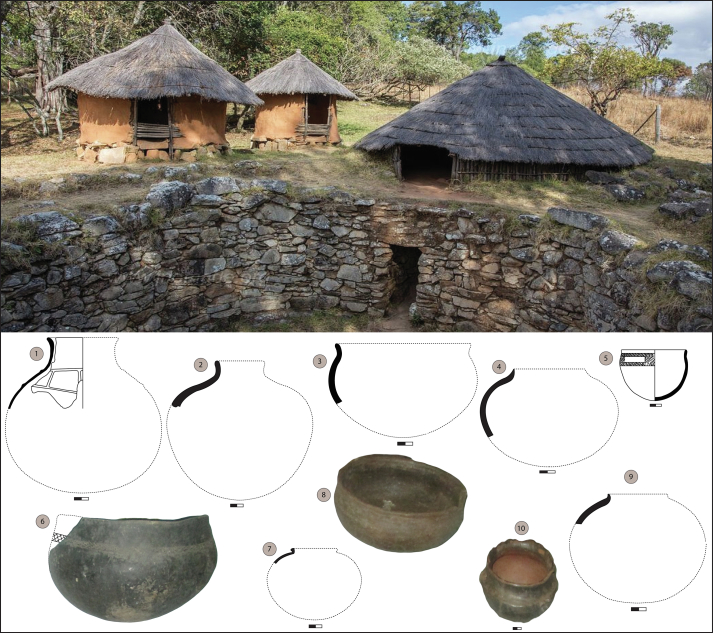

Figure 2.

One of the reconstructed homestead structures centred on a pit structure in the Nyanga National Park thought to have been used for livestock penning. Below is part of the Nyanga ware excavated in the Nyanga agricultural complex. Source: Authors own (Ceramic data was adapted from Bernhard n.d.; Mason, 1933; Summers, 1958; Manyanga, 1995; Soper, 2002,Manyanga and Shenjere, 2012; Nyamushosho and Chirikure, 2020).

The cultural continuity of Nyanga ware into the recent times is denoted by the stylistic similarities with pottery from descendant Shona groups such as the Manyika who gradually succumbed to 19th-century British colonialism (Martin, 1937; Bhila, 1982). Today most of the Manyika descendants populate the area2 drained by the Pungwe and Odzi Rivers (Figure 1). It is in this area where vast samples of broken and complete clay pots belonging to the terrace builders of Nyanga were recovered at archaeological sites such as Bingaguru, Watsomba, Dowe, Pungwe, Mkondwe, Murahwa, Fishpit and many others in the Nyanga National Park (see Figure 1). Since the 16th century, the term Manyika has been erroneously used by Africanists as an umbrella term to bracket the majority of the Shona communities native to eastern Zimbabwe, including the Saunyama, Hwesa, and Maungwe (Ranger, 1989). Thus, the term was more of a geographical expression than an ethnic one (Bernhard n.d.; Beach, 1980; Bhila, 1982; Mupira, 2001). However, now that meanings have been rethought in accordance with the local histories (Bhila, 1982; Ranger, 1989), the term Manyika will be used in this study to refer to the descendants of the Mutasa dynasty which at some point was a tributary dynasty of the Mutapa polity based in northern Zimbabwe (Bhila, 1982: 10, 157; Beach, 2002: 229). The Manyika were attractive for our ethnohistorical study because when compared with other autochthons of the Nyanga archaeological landscape, there is a huge collection of historical records dating back to the 16th century which documented many aspects of their history and culture (Theal, 1898; Bhila, 1982; Gelfand, 1977; Ranger, 1989; Beach, 2002). Furthermore, even though the technology of pottery making is gradually dying among the Manyika as in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa mainly because of modernity downplaying pottery consumption, it has managed to survive into the 21st century (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965; Gelfand, 1974; Gosselain, 1992, 2000; Fredriksen, 2009). Moreover, as similarly experienced in most parts of Africa during the precolonial and colonial eras, pottery of the Manyika fascinated many Europeans. As a result, some aspects relating to how their pots were produced and consumed were documented by traders, hunters, missionaries, travellers, explorers, ethnographers, and colonial administrators. Therefore, it is the main objective of this study to consolidate and examine this archived data to contribute towards a better understanding of everyday life in ancient Nyanga.

3. Methodology

Insights informing our study largely draws upon the ethnohistory of the Manyika. A comprehensive archival study of published and unpublished accounts from the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (Mutare, Bulawayo, and Harare), National Archives of Zimbabwe (Bulawayo), National Free Library of Zimbabwe (Bulawayo), Africa University Kent M. Weeks History and Archives (Mutare) and the University of Cape Town African Studies Library was undertaken on the Manyika archaeology, history, and anthropology. The datasets included manuscripts, books, diaries, maps, photographs, reports, monographs, autobiographies, and journal articles in particular those from early explorers such as Theodore Bent (1892), Carl Mauch ((Burke, 1969)), Martin (1941), Stead (1947); Anne Lawton (1965), Michael Gelfand (1977) and others. However, it must be noted that like other sources from the colonial archive, there were some inconsistencies in some observations, hence we cross-evaluated the data with other scholarly sources. The indigenous experiences of some members of our research team who are native Manyika, and ethnographic insights we collected from elders of the Mutasa dynasty (including potters) also augmented the data. Manyika elders were engaged based on their knowledge of the subject matter and primarily served as the main reviewers who verified and substantiated our data. Ultimately, the combined dataset produced an integrated perspective of the lifecycle of Manyika pottery that stretched from production to discard. However, we undertook this study with the awareness that the worldview and practices of the Manyika like elsewhere were subject to continuity and change (see Lane, 1994/5; (19942000)).

4. Pots among the Manyika: ethnohistorical and ethnographic insights

4.1. From clay sourcing to vessel distribution

Among the Manyika, a pot is known as hari in the local language. In the plural, hari are clay containers for both liquid and solid matter. The art of pot making is locally known as kuumba hari and as largely observed among the broader Shona-speaking groups, pot making is mostly done by women (Aschwanden, 1989; Ellert, 1984; Jacobson-Widding, 1992; Collett, 1993; Lindahl and Matenga, 1995; Ndoro, 1996; Lindahl and Pikirayi, 2010; Nyamushosho, 2017). The available data on Manyika pottery production largely draws from the work of Martin (1941), a Rhodesian farmer and amateur archaeologist who excavated some of the Nyanga stone-walled settlements at Mkondwe farm in Muponda Village in Penhalonga and that of Lawton (1965: 510), a former ethnologist at the then South African Museums3 in Cape Town who collected the data as part of her Master of Arts degree in Social Anthropology at the University of Cape Town.

As usual in most places in southern Africa, the initial phase preceding production of hari is raw material sourcing (Martin, 1941; Lawton, 1965) and generally, a special clay locally known as dongo is used by the potters for making their earthenware. This is meticulously quarried from nearby streams and riverbanks. Nearby termite hills are also potential clay mines since they have large quantities of kaolinite but there are no written records that some of the clay might have been mined from these sources. As noted by Martin (1941: 53) during her observations of two female potters in Muponda Village, clay sourcing can be a household effort where other family members of the potter including young children can give a hand towards quarrying and transportation of the clay. Usually, the quality of the clay and the costs needed to transport it determines the selection of a quarry. Mining of clay is usually done using a hoe (badza) and the quality of clay is evaluated based on its texture and colour (Lawton, 1965). After being dug, the wet clay is covered using lumps of soil to maintain the moisture content and is later transported to the desired destination using reed baskets locally known as tswanda (Martin, 1941; Lawton, 1965). The next stages involve clay preparation and vessel construction. These two processes are mostly carried out in the open space within a homestead (Martin, 1941: 59) or within a specific hut designated as the workshop (Lawton, 1965: 511). Since pottery making is generally a dry weather craft, the working area must be shady to prevent sudden drying of the pots whilst still being manufactured (Lawton, 1965: 485).

Amongst the Manyika clay processing and sourcing overlap; for instance, during quarrying, a potter can refine the gathered clay by removing impurities such as grass, roots, and grit (Martin, 1941: 53). As we noted in Watsomba area, removal of these impurities is also achieved through pounding the clay on a stone slab (guyo) using a wooden pestle (mutwi), a similar practice was also recorded in Muponda area (see Martin, 1941: 53). Clay processing prevents the manufactured wares from cracking and because of that, it is only when the clay is smooth and plastic that vessel construction begins (Martin, 1941: 54; Lawton, 1965: 510).

Most of the Manyika potters design their earthenware in a similar sequence and similar spherical- form which is common in most parts of Africa (see Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965; Gosselain, 1992; Ndoro, 1996; Arthur, 2002; Fowler, 2008; Wynne-Jones and Mapunda, 2008; Lindahl and Pikirayi, 2010; Fredriksen and Bandama, 2016; Thebe and Sadr, 2017). Thus, their anatomy is gendered, hence their physical structure is likened to that of a woman (munhukadzi). Firstly, the body (dumbu) of the pot is moulded; this is followed by the shoulder(bendekete), neck, (mutsipa), lip (muromo), and lastly the base (garo) (Figure 3). As far as the local potters and consumers are concerned, these anatomical parts are integral in determining the shape of a vessel (also see Stead, 1947) but not its local name. Thus, the local classification is built upon the consideration of the shape, and size of the vessel since there is a correlation between the function of a pottery vessel and its size and shape. The moulding process is achieved either using the coiling or pulling method (Martin, 1941; Lawton, 1965). As the vessel nears completion the Manyika potters smoothen its surface. The surface on the inside is smoothened using a curvy fragment of a broken calabash or pot locally known as nhemba whilst a flat-edged instrument (chipariro) is used on the outside (Martin, 1941). The newly formed vessel is also polished on the outer surface using a small quartz pebble (hurungudo) which is usually collected from the nearby river basins. Thus, among the Manyika smoothening preceded polishing the pot's surface (Martin, 1941; Lawton, 1965).

Figure 3.

A Manyika potter with some of her products, photographed around the 1960s (Source: P. Matzigkeit).

Decoration of the earthenware commences after it has been sun-dried for a while (Martin, 1941: 54–56; Lawton, 1965: 511). Most of the clay pot vessels used by the Manyika, regardless of their functions, are undecorated. The occasional motifs (zvidziro in plural) include cross-hatched incisions, graphited triangles, chevron bands, single line, and oblique incisions which are executed on either of the body, shoulder or the neck of a vessel (Martin, 1941: 52, 56; Stead, 1947: 101; Lawton, 1965: 511–516, 524; Jacobson-Widding, 1992: 16). The meanings of decorations on Manyika clay pots range from aesthetics (Martin, 1941: 56) to symbolism (Stead, 1947: 100). For instance, some moulded rib or lug decorations (mitwi) on small-sized necked pots are metaphorically regarded as breasts whilst the incised triangle motifs are associated with elegance (see Stead, 1947: 100; Jacobson-Widding, 1992: 12; Gosselain, 1999: 213).

The duration of drying a pot is generally determined by the prevailing weather. Usually, the pot is fired under an oxidising atmosphere; however, men are not welcome during the firing process since the process is metaphorically rated as disastrous to their potency (Jacobson-Widding, 1992: 10–11). Methods of firing a clay pot depend on the potter's choices and constraints, particularly the availability of the desired fuel. Some Manyika potters observed by Martin (1941) preferred wood from Brachystegia speciformis woodlands locally known as msasa and grass (Martin, 1941: 57), whilst those we interviewed in Watsomba opted for the bark of msasa tree and cow dung (ndove). However, the use of open fires within the homestead, where the firing process ranges between 20 and 120 min is commonly practiced (Martin, 1941: 57–58; Lawton, 1965: 512).

On matters concerning labour organisation and mentorship of the technology of pottery making, ethnohistorical sources on the Manyika potters stress social connections between potters and their students as critical to the mastery of the art (Martin, 1941; Lawton, 1965). However, the skill mostly circulates within families and like most Shona groups it is mostly transmitted through a ‘mother to daughter’ mentorship cycle (Martin, 1941; Jacobson-Widding, 1992; Lindahl and Matenga; Fredriksen, 2009; Pikirayi and Lindahl, 2013). In terms of marketing and distribution, current ethnohistorical data on the Manyika clay pots does not offer much insight. However, as recorded amongst their neighbouring Karanga contemporaries, potters possibly relied on two broad networks for trading their wares: their homesteads and local marketplaces (see Lindahl and Matenga, 1995: 39–46; Lindahl and Pikirayi, 2010: 144). This corresponds with our observations in Nyakatsapa area where one old, retired potter regarded the local market as one of the venues that facilitated the circulation of her clay products.

4.2. From consumption to discard

Though heavily threatened by the proliferation of metal and plastic ware in most homesteads, hari continues to be visible in the daily lives of the modern Manyika. Most ethnohistorical sources emphasize the consumption of clay vessels as kitchenware (midziyo yekubikisa) used by madzimai for preparing everyday meals for their families and in some instances, occasional meals for attendees of public gatherings such as nhimbe/jangano (work parties), kugadzwa humambo/hushe, (chief's inaugurations), mariro/rufu (funerals), chenura (soul-cleansing ceremonies and traditional post-mortem), and many others illustrated in Table 1 (Stead, 1947; Gelfand, 1974, 1977; Bhila, 1982; Ellert, 1984; Gelfand et al., 1985; Jacob-Widding, 1992; Fredriksen, 2009: 100–127). Among the most common culinary vessels is the mukate, also known as tsaiya or tsambakodzi (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947; Gelfand, 1977; Jacobson-Widding, 1992; Fredriksen, 2009). The vessel has no neck to facilitate stirring when cooking, hence its shape ranges from a large to medium-sized wide-mouthed pot with an out-turning lip (see Figure 4). Mukate is primarily used to prepare the most important meal of the day, sadza, a thick porridge made of mapfunde (sorghum), rukweza/njera (finger millet), njeke/magwere (maize), or mhunga (bulrush millet). At secondary level, the vessel is used to prepare nhopi (mashed pumpkin mixed with peanut butter), manhuchu (samp) as well as legume and tuber foods such as fondokoto (cowpeas), nyimo (ground beans), magogoya (colocasia varirty), madhumbe (yams), mufarinya (cassava), majo (colocasia variety), tsenza (livingstone potato) and manhanga (pumpkins). The size of the mukate varies according to the number of people who reside within a homestead. Usually, large-sized mukates are found within homesteads that host large families whilst the medium-sized are associated with smaller families.

Table 1.

Manyika ceremonies and other occasional events associated with pottery consumption.

| Ceremony | Description | Use/s of clay pots | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Rokoto /Mukwerera /Makasva /Mapondoro |

Annual rain petitioning ceremony conducted before the beginning of every agricultural rainy season to enhance fertility. It is conducted at the village or chiefdom-level, at a sacred sanctuary in or outside the village such as under muhacha (parinari curatellifolia) tree or mountain top. Directed by the svikiro (spirit medium) who asks for adequate rains and bumper harvest from Mwari (God) via the royal ancestry | ∗Pots are used to prepare, store, transport, and serve food and drink consumed at the ceremony, particularly beer which is brewed, transported, and served using a variety of clay pots e.g., gate, mbiziro, musudze, pfuko, nhera, mbiya, and hwenga ∗ Storing rain petitioning paraphernalia such as snuff consumed by the mhondoros (ancestral spirits) through their svikiros (mediums |

Gelfand (1974), 1977; Bhila (1982); Ellert (1984); Jacob-Widding (1992); Nyamushosho (2012) |

|

Maganzvo /Doro rematendo /Maponda |

Annual thanksgiving ceremony is conducted after the rainy season where a village collectively gather at a sacred sanctuary such as under muhacha (parinari curatellifolia) tree or mountain top to celebrate the successful agricultural season. | ∗Preparing, storing, transporting, and serving beer used in libations, as well as drinking by the participants ∗Storing rain petitioning paraphernalia such as snuff and water consumed by the mhondoros (ancestral spirits) through their svikiros (mediums) ∗Preparing food feasted at the ceremony |

Martin (1941); Gelfand (1974), (1977); Jacob Widding (1992); Bhila (1982); Ellert (1984); Nyamushosho (2012) |

|

Chenura /Kutamba guva /Kurova guva Kutamba mudzimu |

A soul/spirit cleansing ceremony conducted a year after the death of a family member to bring back and welcome the spirit of a deceased adult individual into contact with its living family members where it can find joy in protecting its own, especially children. The ceremony is also conducted to ascertain the cause of death to the deceased by consulting a n'anga or svikiro to prevent a similar death | ∗Pots are used to prepare food and drink consumed at the ceremony, particularly beer which is brewed, transported, and served using a variety of clay pots e.g. gate, mbiziro, musudze, pfuko, nhera, mbiya, and hwenga ∗ Storing n'anga's or svikiro's paraphernalia such as medicines and snuff used by the n'anga or svikiros in the ritual; |

Gelfand (1974), (1977); Nyamushosho (2012) |

| Kugara nhaka Chigadzamaphihwa | An inheritance ceremony where the wife or husband of the deceased is given a new spouse from the family. The ceremony also includes the distribution of deceased belongings | Pots are used to prepare food and drink consumed at the ceremony, particularly beer which is brewed, transported, and served using a variety of clay pots e.g. gate, mbiziro, musudze, pfuko, nhera, mbiya, and hwenga |

Gelfand (1974), (1977); Nyamushosho (2012) |

| Madiramhamba | A ceremony conducted to pacify the spirit of an angered ancestor | ∗Pots are used to prepare food and drink consumed at the ceremony, particularly beer which is brewed, transported, and served using a variety of clay pots e.g. gate, mbiziro, musudze, pfuko, nhera, mbiya, and hwenga | Gelfand (1974), (1977) |

|

/Kutanda ngozi /Kuripa ngozi |

A ceremony conducted to repatriate, appease, and drive away the avenging spirit of a murdered individual by either offering a lady as a wife or livestock as compensation to the family of the deceased | ∗Pots are used to prepare food and drink consumed at the ceremony, particularly beer which is brewed, transported, and served using a variety of clay pots e.g. gate, mbiziro, musudze, pfuko, nhera, mbiya, and hwenga |

Stead (1947); Gelfand (1974), (1977); Nyamushosho (2012) |

| Kutanda botso | A self-shaming ceremony conducted by son or daughter seeking atonement to get rid of poverty in their life caused by the avenging spirit of their mother whom they would have wronged or assaulted when they were still alive | ∗Pots are used to brew beer consumed at the ceremony using a variety of clay pots e.g. gate, mbiziro, musudze, pfuko, nhera, mbiya, and hwenga | Gelfand (1974), (1977) |

| Madira mombe | A ceremony where a bull is dedicated and named after an ancestor or deceased family head | ∗Pots are used to brew beer and food consumed at the ceremony using a variety of clay pots e.g. gate, mbiziro, musudze, pfuko, nhera, mbiya, and hwenga | Gelfand (1974), (1977) |

| Rufu | A funeral ceremony particularly the death of a wife | ∗Pots are used to brew beer and food consumed at the ceremony ∗Wife is buried with one of her pots placed near her head in the grave |

Gelfand (1974), (1977) |

|

Mahumbwe /Mamhuza |

Manyika version of playing house aimed at fostering gender roles in minors (5–14 years) | ∗Mothers supply cooking pots which are used by senior girls to cook real food | Nyamushosho (2012) |

|

Marooro /Muchato |

A traditional ceremony where husband and wife are joined in matrimony | ∗Ceremony is celebrated by feasting food & beer. The new wife comes in with new clay pots | Gelfand (1974), (1977) |

| Nhimbe/jangano | A community collaboration or work party in tasks like ploughing, weeding & harvesting | ∗Pots are used to brew beer and food consumed at the ceremony | Gelfand (1974), (1977); Nyamushosho and Chirikure (2020) |

| Kugadzwa humambo | Chief inauguration rite | ∗Pots are used to prepare food and drink consumed at the ceremony | Nyamushosho (2012) |

Source: Authors own.

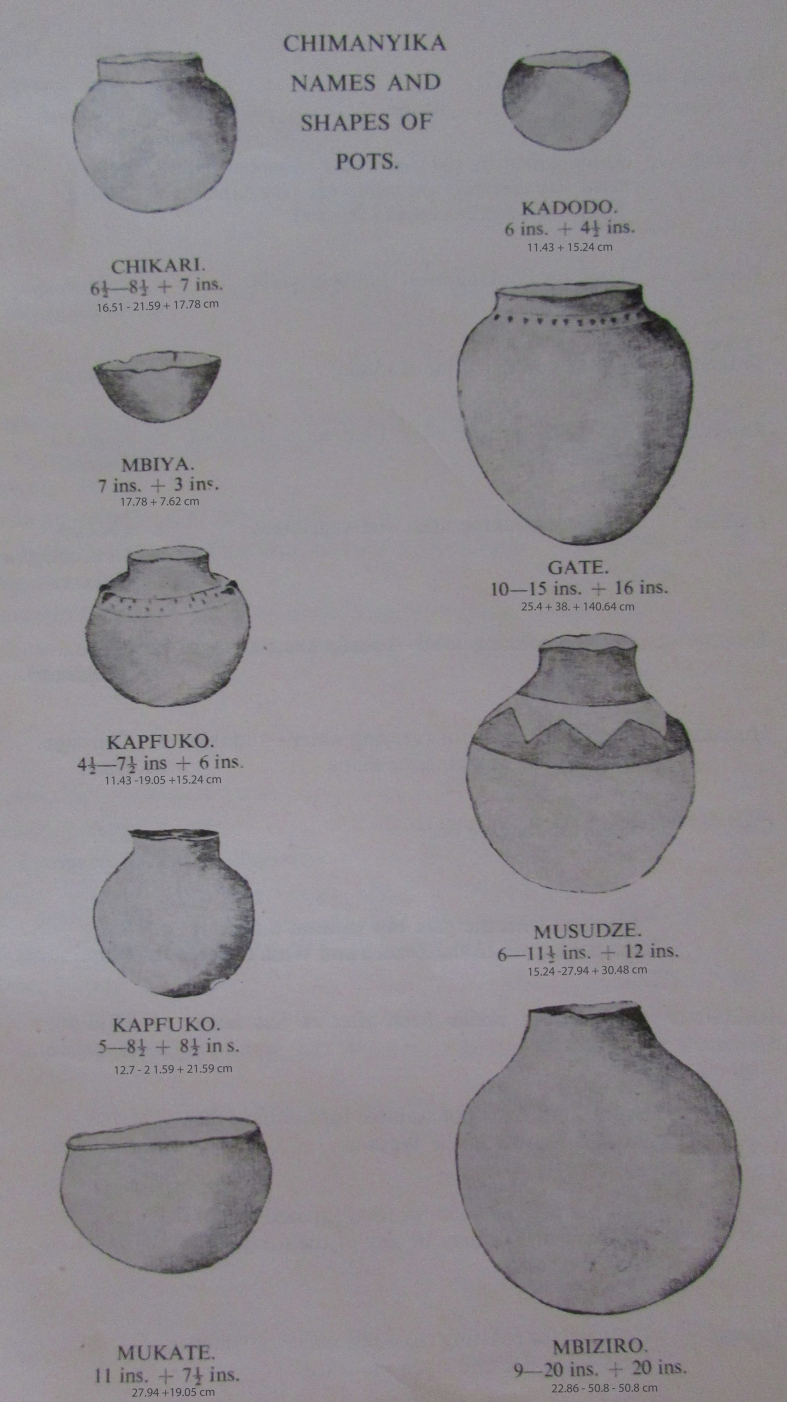

Figure 4.

Manyika pottery vessels recorded by W. H. Stead more than 72 years ago Source: Adapted from Stead (1947:101).

Mbiya, also known as chigapu, chikari, kadodo or hadyana is another culinary vessel popular in most Manyika homesteads (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965). This vessel is produced in a variety of sizes and shapes which range from small wide-mouthed pots with out-turning lips, to medium open bowls with out-turning or straight lips (Figure 4). Mbiya is used to cook usavi (relish) in the form of nyama (meat) and muriwo (vegetables) such as derere (okra), hohwa (mushroom) nhungumira (blackjack), mutikiti (pumpkin leaves), muferefere (melon leaves), nyevhe (cleome gynandra), and mowa (Amaranthus). As common in the broader Shona parlance a smaller version of mbiya or hadyana, is known as chimbiya, chigapu, or chihadyana (see Aschwanden, 1989). This vessel is used by wives to prepare children's porridge (bota) and breakfast for the samusha (family head). The breakfast meal is locally known as chimutsanedako (Bullock, 1927); Stead, 1947; Aschwanden, 1989). Hwenga also known as chayenga, or gango is normally the smallest culinary vessel. This is an open bowl with out-turning or straight lip which is used for making mhandire (roasted shelled maize), or mutsege (roasted shelled peanuts). Generally, culinary vessels are not restricted to facilitate the cooking of food alone, in some instances, they multi-function as serving vessels as shall be discussed below (Schofield, 1948).

The majority of the Manyika kitchenware vessels are usually kept inside the kitchen (imba yekubikira) on a platform with a series of pot stands locally known as chikuva or chidziro (Figure 5). In cases where one does not find them inside the kitchen, either they will normally be on the dara (drying stand) where they are normally sundried after washing (see Figure 6). Manyika kitchenware should not be taken to the river for washing; such acts are symbolically regarded as detrimental to their agricultural prosperity and physical well-being since they are believed to upset the mhondoro (tutelary/lion spirits associated with rain) whom if angered may withhold the rains hence they end up in drought (nzara) (Gelfand, 1974: 79).

Figure 5.

The inside of a reconstructed kitchen hut in the Nyanga National Park showing pot stands on a chikuva. Source: Adapted from Quellet (2014).

Figure 6.

Manyika kitchenware on a drying stand (dara) and a hozi4 in background. Photographed in Nyakatsapa village around the 1960s. Source: P. Matzigkeit.

Apart from cooking, the Manyika use their clay pots as brewing vessels (hari dzedoro). Since time immemorial mhamba (opaque alcoholic beer made from fermented millet or sorghum) and magada (opaque non-alcoholic beer made from fermented millet or sorghum) beverages have always occupied the centre stage of the Manyika liquid foods. Resultantly traditional brewing vessels have been always produced in large numbers to facilitate the brewing of mhamba and magada which are usually consumed as ‘cool drinks’ on daily basis and during occasional ceremonies and rituals such as nhimbe, ndari (beer parties), mukwerera/rokoto (rain-petitioning), maganzvo/matatenda (harvest thanksgiving), kugadzwa humambo/hushe, mariro/rufu, chenura, kuripa/kutanda ngozi (appeasement of avenging spirits), and kugara nhaka (inheritance) (see Table 1). Mhamba is usually reserved for adults and its consumption is sparing unless during special occasions. On the other hand, magada is a beverage for all that is freely consumed anytime by both the young and grownups. Martin (1941) gives a fragmented but insightful description of how Manyika brewing pots are used to make mhamba, nevertheless, the account resonates with the experiences of some of our Manyika colleagues and that of Gelfand (1977).

The brewing process involves various stages in which a very large-sized necked pot with out-turning lip locally known as gate or chikanga is used to malt the cereal grain overnight (kunyika) and boil the malt (masese). Then mbiziro,5 a medium necked pot with out-turning lip is finally used to ferment the masese to produce mhamba; the process normally takes one or two weeks. However, when brewing beer for the village or ward-level agricultural fertility rituals such as rokoto and mandapona, the use of gate and mbiziro is customarily restricted to old women (chembere) who have reached menopause. This is done to avoid pollution of the beer by sexually active and fertile women who are viewed as impure (Gelfand, 1974, 1977). To facilitate the pouring of liquids most of these vessels are usually designed with out-turning lips (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947) and in terms of size their height can stretch up to a metre (Figures 4 and 7). Gate and mbiziro are generally undecorated and mostly today they are produced in small quantities as they are easily being replaced with 200-litre drums and large metal pots used to make mhamba (Ellert, 1984:98). Nevertheless, because several Manyika people still consume mhamba and magada particularly when conducting rituals, they are still visible in most villages.

Figure 7.

Manyika pottery vessels recorded by C. Martin more than 75 years ago. Source: Adapted from Martin (1941:357).

Usually, when the beer is ready for drinking and libations, it is stored and served in the medium to small-sized pots and bowls with out-turning lips such as musudze, chipfuko, and mbiya (Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965; Gelfand, 1977). Musudze also known as chirongo or pfuko, is also used as a container in which women transport water from the source to their respective homesteads. In many instances, the vessel is also used by many families as storage vessels for drinking water (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965). Prominent decorations on, musudze include incised triangle motifs which are mostly executed on its shoulder or neck (Stead, 1947). Chipfuko, a smaller version of musudze is also used to store and serve mhamba or magada. However, in some contexts, the same pot is metaphorically used as a medium for communicating a bride's virginity status during marriage rites (Stead, 1947: Jacobson-Widding, 1992: 12; Gosselain, 1999: 213). For instance, after the first sexual encounter of newlyweds (sensu honeymoon) the groom's aunts (madzitete) check the bedding to find out any form of bleeding; this confirms whether their nephew married a virgin (mhandara) or not. Resultantly, they are obliged by tradition to publicly present the findings of their enquiry to the family of the bride (mwenga). Therefore, if the chipfuko is filled with water to the brim, it means the mwenga was still a virgin when she had sexual intercourse with their nephew, and when half-filled, that means the other way.

Other large and medium-sized vessels are used for storing, transporting, and serving both liquid and solid foods by Manyika (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965; Gelfand, 1977; Ellert, 1984). Typical vessels include denhe, and nhera (see Figures 4 and 7). Denhe also known as muzeka or njeka is a large neckless pot designed with an in-sloping lip for storing upfu (maize meal), dried grain and legumes such as mapfunde, rukweza/njera, njeke, mhunga, fondokoto, nyimo, and pumpkin seeds which are normally consumed as food and at times used as seed for sowing in the forthcoming planting season. Based on the average measurements we recorded during our ethnographic survey, the diameter and height dimensions of denhe range between 27-45 cm and 40–100 cm respectively, and generally its volume can go up to thirty litres. In the absence of denhe, gate can be used to serve its function since its capacity is also larger. For instance, it can hold up to 50 kg of cereal (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947 Ellert, 1984). As we noted, nhera is the smallest vessel in most homesteads. This is a semi-hemispherical bowl with a straight lip that is used to store munyu (salt), mafuta (vegetable or animal fat), or zvirungo (spices) used during cooking. At the secondary level, nhera is used to store mudhombo (traditional stuff) which is mostly "snuffed" or inhaled into the nasal cavity by masvikiro (spirit mediums) to facilitate kusvikirwa (process of the possession of the spirit medium by the spirit of the dead) during ritual activities such as maganzvo.

Rarely does one find the big brewing pots such as gate and mbiziro stored inside the imba yekubikira. Mostly because they are large-sized and occasionally used, they are normally kept inside the granary (hozi) where they will only be brought out if there is a need to brew. The same also applies to denhe. In as much as some denhe vessels maybe placed in the imba yekubikira to facilitate access to upfu for preparing everyday meals such as sadza, most denhe are usually placed inside the hozi as ‘silos’ for containing harvested and processed grain and legume crops such as mapfunde, rukweza/njera, njeke, mhunga, fondokoto, nyimo and pumpkin seeds which are normally preserved for future consumption and as seed for the forthcoming planting season.

Clay pot vessels also feature as household ware in child plays and games such as mahumbwe (Gelfand, 1960: 36–37). This is a traditional Shona version of the playing house game which is aimed at fostering gender roles and norms for minors aged between 5 and 14 years. Hence, they imitate their parent's behaviour by making mock shelters and pretending to have their own families in the open (harvested) fields (Gelfand, 1960: 36). Mothers supply necessary kitchenware such old mbiya and mukate which are used by senior girls (who act as mothers) to cook sadza for their families, whilst big boys (fathers) drink maheu from beer vessels such as chipfuko making it as if they are drinking real beer (Gelfand, 1960: 37).

Not much has been recorded concerning longevity, recycling, and discard patterns of Manyika pottery, but considering the cursory mentioning by some ethnographers, there is a possibility that ritual vessels have a better life span when compared to quotidian vessels which easily break as a result of constant use in the kitchen. For instance, as observed by Gelfand (cited below), some beer pots can be intentionally discarded on remote sanctuaries such as hills or around sacred trees such as muchakata (parinari curatellifolia) which are regarded as the abode of the mhondoro (lion spirits) during rituals such as maganzvo or mandapona.

“We have left your pots of beer at home, but you may drink this pot of beer, we have brought it to you.” (Gelfand, 1974: 81)

Manyika pottery vessels are also intentionally discarded as mortuary goods when a married woman is buried with some of her kitchenware (Gelfand, 1977: 45). On the other hand, small-sized pots or bowls containing a concoction prepared by diviners (n'anga) for their clients are intentionally broken into sherds on a crossroad (mharadzano) as a ritual to set them free from mashavi (evil spirits) (Gelfand et al., 1985: 77, 340). In some instances, sizeable potsherds from broken pots (Figure 8) were reused as hwenga (pans), zvirugu (chicken coups), dustpans, or platters for feeding domesticated animals (see Martin, 1941; Lawton, 1965; Gelfand, 1974; 1977; Ellert, 1984).

Figure 8.

A discarded denhe now secondarily used as a chicken coup. Source: Authors own.

5. Discussion: integrating the ethnohistorical insights and the archaeology

The Manyika, ethnohistorical data enables us to situate ceramics recovered from the Nyanga agricultural complex into the everyday context that possibly governed their life cycle right from production to discard. Firstly, the data throws light on the processes and complexities of pottery production as handicraft and these are concordant to the archaeological record (sensu Stark, 2003). For instance, in terms of clay procurement strategies, there is a high probability that suitable clay was consciously acquired from openly accessed streams and riverbanks located in the vicinity, paying close attention to tangible and intangible aspects such as mineralogy, texture, plasticity, temper levels, taboos, restrictions and even the cost of transporting the clay. This was done for particular reasons which reflect the potter's technical choices and constraints in resource procurement, which are all influenced by local factors such as experience, access, and geology. Parallel trends have been discovered elsewhere among the Twa potters of Rwanda and the Zulu potters in the Thukela Basin, South Africa, where the formula for acquiring suitable clay is a matter of the ‘feel’ of it (Kohtamaki, 2010: 304–305; Fowler, 2011: 180–183). Thus, the Manyika ethnohistorical data enables us to identify the impalpable skills needed to procure clay for clay pot craft production, which is missing in the current ceramic database on the archaeology of eastern Zimbabwe. There is still a need for more fieldwork devoted to the location of clay sources, nevertheless, there is a high probability that the local drainage basins such as Pungwe, Utare, Odzi, Odzani, Nyadiri, Rebvuwe, Mkondwe, and Honde Rivers might have been utilised as clay sources by the makers of Nyanga pottery, particularly those residing at stonewalled enclosures such as Mkondwe, Burnaby, Watsomba, Dowe, Fishpit, and many others in the Nyanga National Park (Figure 2).

vThe ethnohistorical insights also help to uncover what Cathy Lynne Costin (2000: 391) calls ‘hidden’ labour during raw material mobilisation and vessel production processes in the archaeological record. This refers to those tasks performed by assistants who are not the artisans themselves. For example, whilst the focus of her study was on the widow of Chief Mutasa as the main potter, Martin (1941: 53) makes mention of the daughter-in-law and the toddler giving a hand in various production sequences including clay extraction, transportation, preparation, vessel construction, and firing. However, all these efforts are indiscernible to the archaeologist who only grapples with a reconstructed pot as a product of the solo effort by one potter who fashioned the entire vessel from bottom to the lip. The same trends were discovered by Mercader et al. (2000: 179) amongst the Lese and Budu potters of the Ituri rainforest in the north-eastern parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where women potters were occasionally escorted by other ladies who helped in the clay extraction processes. Elsewhere in the Philippines, London (1991) highlighted the recruitment of assistants by Paradijon potters to meet their production targets. These examples demonstrate the elusive role of social ties in the process of resource procurement, vessel fashioning, and skill circulation. Hence, the probability is very high that Nyanga potters were predominately women who extensively relied on labour from their kin to achieve their production targets.

The Manyika ethnohistorical data also throws light on the spatial context of pottery craft production and distribution in the Nyanga agricultural complex. According to the ethnohistorical data, pot making is a dry weather handicraft mostly done within homestead spaces either in a designated hut or open space, however, not far distant from clay sources (Martin, 1941: 59; Lawton, 1965: 511). Considering this we can tentatively ascribe open spaces inside and outside the stone enclosures previously identified as residential zones at sites such as Fishpit, and Mkondwe (Martin, 1937:1038; Summers, 1958:65; Soper, 2002:182), as also activity areas for pottery craft production and retailing (see Figure 9). There is also a possibility that some spherical hammerstones recovered at Mkondwe (Mason, 1933:574) might have been used for processing clay to prevent the manufactured pots from cracking. Whilst we are not certain on where exactly pottery was moulded, based on the surface colour of Nyanga pottery – which ranges between black, brown and grey, (pointers to open firing, sensu Manyanga, 1995: 38) – it is clear that the firing process took place in the open space encircling the pit structures and enclosures where other crafts such as iron smelting were undertaken (see Summers, 1958: 61, 98–101; Soper, 2002: 115–117; Chirikure and Rehren, 2004: 152). This is corroborated by ethnoarchaeological data from the neighbouring Shona cluster groups in Zimbabwe (Lindahl and Matenga, 1995: 31; Pikirayi and Lindahl, 2013) and other Sub-Saharan Africa ethnic groups, such as the Ari, Oromo, Gulo-Makeda, and Gamo of Ethiopia (Lyons and Freeman, 2009: 87; Wayessa, 2011: 307; Arthur, 2013: 8,12), Kikumbiro of Buganda (Giblin and Kigongo, 2012: 70); Mafia of coastal Tanzania (Wynne-Jones and Mapunda, 2008: 1), Luo of Kenya (Dietler and Herbich, 1994: 462), and Zulu of South Africa (Fowler, 2011: 193) which highlight household space at different agropastoral sites as shared space that accommodated production and distribution of various crafts such as pottery, beads, cotton cloth, metals, and music instruments. Nevertheless, these conclusions should be substantiated by further ethnoarchaeological research since activity areas for the ceramic chaîne opératoire cannot be homogenised (Costin, 2000; Stark, 2003).

Figure 9.

Above are reconstructed functional classes of pottery recovered at Later Iron Age settlements in the Nyanga uplands Source: Authors own (Ceramic data was adapted from Bernhard n.d.; Mason, 1933; Summers, 1958; Soper, 2002). Below is the site map of Fishpit depicting houses and open space that was probably used for crafting pottery (Adapted from Soper, 2002:181).

The Manyika ethnohistorical data offer archaeologists an opportunity to access the socioeconomic settings that possibly governed Nyanga potters and their handicrafts. Thus, from the modern Manyika we are presented with potters who operate on a part-time basis (Martin, 1941; Lawton, 1965). Whilst these artisans have the liberty to fashion their products using their own stylistic and decorative discretion which imprints desired aesthetics or metaphors, the potters are nonchalant about the stylistic attributes of their products, so long as they can fulfil their function. Consequently, the common denominator between pottery from modern and ancient Nyanga is the abundance of unadorned ware (see Figures, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 11). The reason why archaeologists have mostly recovered rarely decorated pottery in the complex is probably owing to the potter's stylistic choices in light of their everyday roles rather than incapacity to innovate (contra Summers, 1958). Thus, perhaps the answer to the burning question archaeologists poses on why Nyanga pottery (and other potteries from neighbouring Iron Age sites in southern Africa, see David et al., 1988; Nyamushosho, 2020) was rarely decorated (i.e. Summers, 1958; Manyanga, 1995; Soper, 2002) is because it was largely quotidian. The paucity of graphite burnishing on the recorded ethnographic vessels (Martin, 1941: 56; Lawton, 1965: 511) parallels typological data of Nyanga pottery recovered from both the upland and lowland sites (see Mason, 1933: 574–578; Summers, 1958: 139–146; Manyanga, 1995: 40; Soper, 2002: 251–256; Shenjere, 2011: 314). Thus, considering the rarity of local graphite deposits (Summers, 1958: 313) there is a possibility that some potters in the Nyanga archaeological complex outsourced graphite from their neighbours (Summers, 1958: 313). More research is needed to identify these places.

The Manyika ceramic ethnohistorical and ethnographic data elucidates the everyday roles of clay pots in the lives of the Nyanga agropastoralists (see Nyamushosho and Chirikure, 2020 for a detailed discussion). Reconstruction of some of the broken and partially complete pots recovered at Mukondwe, Murahwa, Fishpit, and other upland settlements in the Nyanga National Park revealed a range of functional classes that probably governed the use-life of Nyanga ware. As demonstrated in Figure 9, these medium to small-sized vessels included mbiya (2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13), chimbiya (10, 11, 15), and mukate (16). Basing on their reconstructed sizes and shapes, all these vessels likely served as kitchenware which was used to prepare and serve everyday meals (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965; Jacob-Widding, 1992; Fredriksen, 2009). This is supported by the presence of soot stains on the surfaces of some of the vessels (see Figure 9) which probably accumulated as a result of continuous exposure to fire during cooking. Such a routine weakened the fabric of kitchenware, hence shortening its use-life. Perhaps this explains why most of the archaeologists working in the Nyanga agricultural complex recovered thousands of broken potsherds with soot stains (i.e. Randall-MacIver, 1906; Mason, 1933; Summers, 1958; Manyanga, 1995; Soper, 2002; Manyanga and Shenjere, 2012). Some of the cereal, legume, and animal food products that were cooked in the Nyanga ware probably included ground beans (nyimo), sorghum (mapfunde), game meat, and beef (nyama) from species such as Impala (mhara), buffalo (nyati), common cuiker (mhembwe), waterbuck (dhumukwa), and cattle (mombe). Botanical, and faunal residues of these cultigens, and mammals were recovered in the Nyanga National Park (see Cook, 1958:152–158; Wild, 1958:175; Jonsson, 2002:249). Unless residue analysis is undertaken it will continue to be a challenge for archaeologists to identify the exact foods that were prepared in these vessels. Nonetheless, as part of the kitchenware, all these vessels were obviously kept on zvikuva (plural – see Figure 5) inside kitchens (dzimba dzekubikira). Some of the dzimba dzekubikira included those excavated by Soper (2002:180–186) at Fishpit (Figure 9), and other house floors uncovered in the neighbouring settlements (see Mason, 1933; Martin, 1937; Summer, 1958).

The large to medium-sized vessels illustrated in Figure 9 likely served as beer brewing, and water (Including beer) storage vessels (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965). Roger Summers' (1958: 144-145) assumption that Nyanga societies that resided in the uplands did not produce or consume large storage vessels such as gate, and musudze, due to poverty of grain for brewing is undermined by the presence of these vessels. Additionally, his argument is too simplistic since it challenges their innovation capabilities. Whilst it is indisputable that the Nyanga uplands are heavily affected by soil erosion which makes it difficult to sustain extensive cereal agriculture as compared to the lowlands; there is little probability to believe that all the uplanders were not able to agriculturally adapt to this mountainous landscape. In fact, as recently revealed by the work of Robert Soper (2002) and the late Steve Chirawu (Chirawu et al., 1999), it is indubitable that cereal agriculture formed the basis of the subsistence of the Nyanga uplanders since they relied on terracing, intercropping, animal manure (mufudze), and many other agricultural adaptations which enhanced soil fertility. Above all, as highlighted by the ethnohistorical data, cereal beer has deep antiquity among the Manyika, and most importantly it is part of the liquid material culture that forms the lifeblood of the Manyika social life (Martin, 1941; Stead, 1947; Lawton, 1965; Gelfand, 1974; Bhila, 1982; Ellert, 1984). Therefore, there is a high probability that most households in the Nyanga uplands including those recorded at Mukondwe (Mason, 1933) and Fishpit (Soper, 2002) owned brewing and storage pots that were used at social gatherings that possibly included nhimbe, ndari, mukwerera, mariro, kugara nhaka, maganzvo, and many other ceremonies enlisted in Table 1 which are held in private or public spaces (see Stead, 1947; Gelfand, 1974; 1977; Bhila, 1982; Ellert, 1984; Gelfand et al., 1985; Jacob-Widding, 1992). Nevertheless, some of these vessels did not necessarily have the metric attributes that were anticipated by Summers (1958). This omission is prevalent in African archaeology (see Hall, 1983; Gosselain, 1992; Ndoro, 1996; Ogundele, 2006; Pikirayi, 2007; Ashley, 2010; Mtetwa et al., 2013; Nyamushosho, 2017). Application of Eurocentric methods (that prioritise rims, decorations, and shapes of archaeological ceramics without attention to other body parts and overall vessel sizes) has robbed many ceramists the opportunity to appreciate the variability of pottery classes and uses. Ultimately, they fail to produce results that resonate with the communities who manufactured or used the pots in their everyday life. Elsewhere in east-central Arizona, Skibo et al.’s (1989) reconstruction of broken sherds recovered from Broken K Pueblo revealed inconsistencies in stylistic typologies that had been created by earlier researchers. Thus, the point to draw out is that the study at hand underscores the need to capture a wider array of descriptive variables, at the same time it is vital to be mindful of taphonomic processes and the challenges of estimating vessel sizes.

The lifecycle of clay pots produced and consumed by both the uplanders and lowlanders in the Nyanga complex was governed by some socially constructed restrictions, myths, and taboos conversant to the contemporary Manyika worldview. Whilst it is impossible for archaeology to directly uncover these intangible aspects, it is likely that part of the restrictions, prevented the washing of kitchenware in riverbeds (Gelfand, 1974: 79). Such acts of spiritual pollution were detrimental to their livelihood. They angered the Manyika ancestors, causing them to withhold the rains; these were key to agricultural prosperity.

Concerning discard, there is a possibility that some broken pottery vessels excavated at Mukondwe alongside a young female adult skeleton (see Mason, 1933; Galloway, 1937; Martin, 1937) were intentionally discarded as grave goods together with glass beads and metal bangles. This is corroborated by a similar mortuary practice recorded among the Manyika, where a married woman is buried with some of her kitchenware and jewellery upon death (Gelfand, 1977: 45). Furthermore, in as much as we do not have sufficient data, it is also possible that Nyanga pots were recycled upon breakage. Thus, large sherds from broken pots possibly regained a new lease on life as zvirugu (chicken coups), hwenga (pans), dustpans, or a platter for feeding domesticated animals (i.e. chickens, cats, and dogs), transporting marasha (hot ambers) for making fire or burning powdered concoctions prepared by n'anga (diviners) for healing illnesses (matenda) (Gelfand et al., 1985: 20).

6. Conclusion

This ethnohistorical study highlights the potential of African-centred knowledge as an alternative framework for illuminating the lifecycle of Iron Age pottery from precolonial Nyanga. By situating the pottery in the Manyika worldview and practices, we were able to derive refreshing insights that shaped the production, distribution, consumption, and discard patterns of vessels that possibly served as storage, brewing, or kitchenware. In as much as we have tried to generate an understanding of the everyday and occasional roles of clay pots in ancient Nyanga, and how they contributed to the development of the agricultural complex; we do not render these chaîne opératoire processes as captured in stasis since the 14th century. As we signalled earlier, this is a work in progress. We will conduct more ceramic ethnoarchaeological studies dedicated to fill the missing dimensions and establish our propositions. Whilst it is indubitable that much of our data was drawn from the colonial archive often marred by colonial prejudice, it is not surprising that when compared to the archaeological interpretations, the ethnohistorical dataset was more consistent with the Manyika worldview and practices. Thus, unlike ethnographers and historians, it appears archaeologists created a different version of Nyanga past difficult for most of the Manyika to relate with it. More importantly, we have shown here that what is required for archaeology to be qualified as decolonised is not necessarily doing away with the colonial archive or restricting the academy to Afropolitan scholars but approaching material culture in a more holistic manner that resonates with local ontologies, epistemologies, and practices. When viewed using a global lens, the implications of this study appeal to wider debates in archaeology, and (ceramic) ethnoarchaeology that calls for a transformation in knowledge production (i.e. Hall, 1983; Dietler and Herbich, 1989; Stahl, 1995; Ndoro, 1996; Stark, 2003; Karega-Munene and Schmidt, 2010; Lane, 2011; Pikirayi, 2015; Chirikure, 2016, Chirikure, 2020; Cunningham and MacEachern, 2016; Haber, 2016; Gosselain, 2016; Chirikure et al., 2017). Perhaps, one lesson that could be derived from our ongoing research is that there is enrichment in engaging local communities as key stakeholders in validating archaeological knowledge. In some ways, this resonates with the sort of 'slow science' advocated by Gosselain (2011) and others (i.e. Cunningham and MacEachern, 2016) which accentuate the need to give local communities a meaningful voice in knowledge production.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Robert T. Nyamushosho: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Njabulo Chipangura, Foreman Bandam, Shadreck Chirikure, Munyaradzi Manyanga: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Takudzwa B. Pasipanodya: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

Sections of this paper were presented at the “Engaged Scholarship in Africa: A tribute to Samir Amin Conference”, held at the University of Cape Town (UCT) Centre for African Studies in September 2019 and the “Extracting the past from the present International and Interdisciplinary Conference on African Precolonial History”, recently held in March 2021. We are grateful to the organisers for inviting one of us (RTN) to present. We thank our anonymous reviewers, colleagues, and students, whose comments and suggestions proved useful in shaping this paper. Support from our respective institutions is also sincerely acknowledged with gratitude, particularly the UCT Re-centring AfroAsia Project and the Archaeology Department.

Footnotes

Also known as tsapi or dura. It is basically a small-elevated hut made of dhaka and pole thatched with grass which is normally serves as a repository for dried grain and legumes for each homestead (Bhila, 1982).

Also known as Inyanga (see Summers, 1958).

Currently and commonly known as Mutasa District.

Now known as Iziko Museums.

In some texts, mbiziro (see Figure 7) is presented as a unique big pot with two mouths whose use restricted to chiefs (madzimambo) and headmen (madzisadunhu), at ceremonies such as maganzvo (Martin, 1941: 53; Ellert, 1984: 103).

References

- Arthur J.W. Pottery use-alteration as an indicator of socio-economic status: an ethnoarchaeological study of the Gamo of Ethiopia. J. Archaeol. Method Theor. 2002;(9):331–355. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur J.W. Transforming clay: Gamo caste, gender, and pottery of south western Ethiopia. Afr. Stud. Monogr. 2013;46(Suppl.):5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Aschwanden H. Mambo Press; Gweru: 1989. Karanga Mythology. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley C. Towards a socialised archaeology of ceramics in great lakes. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2010;27(2):135–163. [Google Scholar]

- Beach David.N. Mambo Press; Gweru: 1980. The Shona and Zimbabwe: 1900-1850. [Google Scholar]

- Beach D.N. Nyanga: Ancient Fields, Settlements and Agricultural History in Zimbabwe. Soper, R. Memoirs of the British Institute in Eastern Africa: Number 16. British Institute in East Africa; London: 2002. History and archaeology in Nyanga. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard, F. O. n.d. Ancient Village Site on Murahwa‟s hill, Umtali. Report on Excavations 1964-1968. Unpublished Archaeological Survey of Zimbabwe report. Museum of Human Sciences, Harare.

- Bhila H.H.K. Essex: Longman; Harlow: 1982. Trade and Politics in a Shona Kingdom: the Manyika and Their African and Portuguese Neighbours; pp. 1575–1902. [Google Scholar]

- Chipangura N. Artisanal and small-scale mining (chikorokoza ) of gold in the eastern highlands of Zimbabwe: archaeological, ethnographic and historical characteristics. Azania: Archaeol. Res. Afr. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Chipangura N., Nyamushosho R.T., Pasipanodya T.B. Living site, living values: the Matendera festival as practice in community conservation and presentation. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2019;14:16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chirawu S. University of Zimbabwe; Harare: 1999. The Archaeology of Ancient Agriculture and Settlement Systems in Nyanga Lowlands. Unpublished M.A Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Chirikure S. ‘Ethno’ plus ‘archaeology’: what’s in there for Africa (ns)? World Archaeol. 2016;48(5):693–699. [Google Scholar]

- Chirikure S. Routledge; London: 2020. Great Zimbabwe: Reclaiming a ‘Confiscated’ Past. [Google Scholar]

- Chirikure S., Rehren T.H. Ores, furnaces, slags, and prehistoric societies: aspects of iron working in the Nyanga Agricultural Complex, AD 1300–1900. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2004;21:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chirikure S., Nyamushosho R.T., Chimhundu H.H., Dandara C., Pamburai H.H., Manyanga M. Concept and knowledge revision in the post-colony: mukwerera, the practice of asking for rain amongst the Shona of southern Africa. In: Manyanga M., Chirikure S., editors. Archives, Objects and Landscapes. Multidisciplinary Approaches to Decolonised Zimbabwean Pasts. Langaa Publishers; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chirikure S., Nyamushosho R., Bandama F., Dandara C. Elites and commoners at Great Zimbabwe: archaeological and ethnographic insights on social power. Antiquity. 2018;92(364):1056–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Collett D.P. Metaphors and representations associated with pre-colonial iron-smelting in eastern and southern Africa. In: Shaw T., Sinclair P.J.J., Andah B., Okpoko A., editors. The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns. Routledge; London: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cook H.,B.,S. Inyanga: Prehistoric Settlements in Southern Rhodesia. Summers, R. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1958. Fossil animal remains from Inyanga. [Google Scholar]

- Costin C.L. The use of ethnoarchaeology for the archaeological study of ceramic production. J. Archaeol. Method Theor. 2000;7:377–403. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J.J., MacEachern S. Ethnoarchaeology as slow science. World Archaeol. 2016;48(5):628–641. [Google Scholar]

- David N., Kramer C. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2001. Ethnoarchaeology in Action. [Google Scholar]

- David N., Sterner J., Gavua K. Why pots are decorated. Curr. Anthropol. 1988;29(3):365–389. [Google Scholar]

- Dietler M., Herbich I. Tich matek : the technology of Luo pottery production and the definition of ceramic style. World Archaeol. 1989;21:148–164. [Google Scholar]

- Dietler M., Herbich I. Ceramics and ethnic identity: ethnoarchaeological observations on the distribution of pottery styles and the relationship between the social contexts of production and consumption. In: Binder D., Audouze F., editors. Terre cuite et soci´et´e: la c´eramique, document technique, ´economique, culturel, XIVe Rencontre Internationale d’Arch´eologie et d’Histoire d’Antibes, ´ Juan-les-Pins. Editions APDCA; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ellert H. Longmans; Harare: 1984. Material Culture of Zimbabwe. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler K.D. Zulu pottery production in the lower Thukela Basin, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South. Afr. Humanit. 2008;20:477–511. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler K.D. The Zulu ceramic tradition in Msinga, South Africa. South. Afr. Humanit. 2011;23:173–202. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen P.D. University of Bergen; Norway: 2009. Transformations in Clay: Material Knowledges, Thermodynamic Spaces and the Moloko Sequence of the Late Iron Age (AD 1300–1840) in Southern Africa. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen P.D., Bandama F. The mobility of memory: space/knowledge dynamics in rural potting workshops in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Azania. Archaeol. Res. Africa. 2016;51:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fripp C., Wells L.H. Excavations in a pit circle at Inyanga, S. Rhodesia. South Afr. J. Sci. 1938;35:399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand M. Mahungbwe [Shona custom] NADA. 1960:36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand M. The Mhondoro cult among the Manyika peoples of the eastern region of Mashonaland. NADA. 1974;11:64–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand M. Mambo Press; Gweru: 1977. The Spiritual Beliefs of the Shona: A Study Based on a Field Work Among the East Central Shona. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand M., Mavi S., Drummond R.B., Ndemera B. Mambo Press; Gweru: 1985. The Traditional Medical Practitioner in Zimbabwe: His Principles of Practice and Pharmacopoeia. [Google Scholar]

- Giblin J.D., Kigongo R. The social and symbolic context of the royal potters of Buganda. Azania: Archaeolog. Res. Afr. 2012;47(1):64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselain O.P. Technology and style: potters and pottery among Bafia of Cameroon. Man. 1992;27(3):559–586. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselain O.P. In pots we trust. The processing of clay and symbols in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Mater. Cult. 1999;4:205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselain O.P. Materializing identities: an African perspective. J. Archaeol. Method Theor. 2000;7:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselain O.P. Slow Science – La Désexcellence. Uzance: Revue d’Ethnologie Européenne De La Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles. 2011;1:128–140. [Google Scholar]

- Haber A. Decolonizing archaeological thought in south America. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2016;45:469–485. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. Tribes, traditions and numbers: the American model in southern African Iron Age ceramic studies. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 1983;38:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder I., Hutson S. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2003. Reading the Past: Current Approaches to Interpretation in Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman T.N. Southville. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press; 2007. Handbook to the Iron Age: the Archaeology of Pre-colonial Farming Societies in Southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson-Widding A. Pits, pots and snakes: an anthropological approach to ancient. Afr. Symbols Nordic J. Afr. Stud. 1992;1(1):5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson J. Nyanga: Ancient Fields, Settlements and Agricultural History in Zimbabwe. Soper, R. Memoirs of the British Institute in Eastern Africa: Number 16. British Institute in East Africa; London: 2002. Report on the identification of plant macrofossils. [Google Scholar]

- Katsamudanga S. University of Zimbabwe; 2007. Environment and Culture. A Study of Prehistoric Settlement Patterns in the Eastern highlands of Zimbabwe. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Kohtamaki M. An ethnoarchaeological study of Twa potters in southern Rwanda. Azania: Archaeol. Res. Afr. 2010;45(3):298–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lane P. The use and abuse of ethnography in the study of the southern African iron age. Azania. 1994/1995;29/30:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lane P.J. Possibilities for a postcolonial archaeology in Sub-Saharan Africa: indigenous and useable pasts. World Archaeol. 2011;43(1):7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton A. Vol. 1. University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 1965. (Bantu Pottery of Southern Africa). MA Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl A., Matenga M. Present and past: ceramics and homesteads: an ethno-archaeological study in the Buhera district, Zimbabwe. Stud. Afr. Archaeol. 1995;11 Department of Archaeology. Uppsala: Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl A., Pikirayi I. Ceramics and change: an overview of pottery production techniques in Northern South Africa and Eastern Zimbabwe during the first and second millennium AD. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2010;2:133–149. [Google Scholar]

- London G.A. Standardization and variation in the work of craft specialists. In: Longacre W.A., editor. Ceramic Ethnoarchaeology. University of Arizona Press; Tucson: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Manyanga M. University of Zimbabwe; Harare: 1995. Nyanga Pottery: a Classification of the lowland and upland Ruin Wares. BA Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Manyanga M., Shenjere P. The archaeology of the northern Nyanga lowlands and the unfolding farming community sequence in northeastern Zimbabwe. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 2012;67:244–255. [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. Prehistoric burials at Penhalonga. South Afr. J. Sci. 1937;33:1037–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. Manyika pottery. Proc. Rhodesian Sci. Assoc. 1941;38:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mason A.,Y. The Penhalonga Ruins. S, Rhodesia. South Afr. J. Sci. 1933;30:559–581. [Google Scholar]

- Mercader J., Garcia-Hera M., Gonzalez-Alvarez I. Ceramic tradition in the African forest: characterisation analysis of ancient and modern pottery from Ituri, D.R. Congo. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2000;27(3):163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P.J. Excavating Nyanga agricultural history Nyanga: ancient fields, settlements and agricultural history in Zimbabwe. J. Afr. Hist. 2004;45:319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Mtetwa E., Manyanga M., Pikirayi I. Ceramics in Zimbabwean archaeology: thinking beyond the traditional approaches. In: Manyanga M., Katsamudanga S., editors. Zimbabwean Archaeology in the Post-independence Era. Sapes books; 2013. (Harare). [Google Scholar]

- Mupira P. Local histories, oral traditions and the archaeological landscape in Nyanga district, north-east Zimbabwe. Zimbabwean PreHistory. 2001;24:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mupira P. Losing and repossessing land and ancestral landscapes: archaeology and land reforms in eastern highlands of Zimbabwe. In: Relaki M., Catapoti D., editors. An Archaeology of Land Ownership. Routledge; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murimbika M. University of the Witwatersrand; Johannesburg: 2006. Sacred powers and Rituals of Transformation: an Ethnoarchaeological Study of Rainmaking Rituals and Agricultural Productivity during the Evolution of the Mapungubwe State, Ad 1000 to Ad 1300. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Ndoro W. Towards the meaning and symbolism of archaeological pottery assemblages. In: Pwiti G., Soper R., editors. Aspects of African Archaeology: Papers from the 10th Pan African Association for Prehistory and Related Studies. University of Zimbabwe Publications; 1996. (Harare). [Google Scholar]

- Nyamushosho R.T. 2012. Ethnoarchaeological Study of Pottery Vessels from, north-eastern Zimbabwe. Unpublished field notes. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamushosho R.T. Gweru. Midlands State University; 2013. Identity and Connections: an Ethnoarchaeological Study of Pottery Vessels from the Saunyama Dynasty and the Nyanga Archaeological Complex in Northeastern Zimbabwe. BA Honours Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamushosho R.T. Ceramic ethnoarchaeology in Zimbabwe. Int. Res. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2014;3(2):17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamushosho R.T. Aspects of consumption and symbolism: a ceramic ethnoarchaeological study of ritual vessels among the Saunyama of north-eastern Zimbabwe. In: Manyanga M., Chirikure S., editors. Archives, Objects and Landscapes. Multidisciplinary Approaches to Decolonised Zimbabwean Pasts. Langaa Publishers; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamushosho R.T. University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2020. States, agency, and Power on the ‘peripheries’: Exploring the Archaeology of the Later Iron Age Societies in Precolonial Mberengwa, CE 1300-1600s. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamushosho R.T., Chirikure S. Archaeological implications of ethnographically grounded functional study of pottery from Nyanga, Zimbabwe. Quat. Int. 2020;555:150–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ogundele S.O. Prospects and Challenges of oral traditions and ethnography for archaeological reconstructions: a case study of Tivland, Nigeria. Anistoriton J. 2006;10:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pasipanodya T.B. University of Zimbabwe; Harare: 2016. Ancient and Modern Terracing in Charamba Communal Area in Northern Nyanga: a Comparative Study of Their Design and Uses. M.A Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Philipson D.W. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2005. African Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Pikirayi I. Taking Southern African ceramic studies into the twenty-first century: a Zimbabwean perspective. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 1999;16(3):185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Pikirayi I. AltaMira Press; Walnut Creek: 2001. The Zimbabwe Culture: Origins and Decline of Southern Zambezian States. [Google Scholar]

- Pikirayi I. Ceramics and group identities: towards a social archaeology in Southern African Iron Age ceramic studies. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2007;7(3):286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Pikirayi I. The future of archaeology in Africa. Antiquity. 2015;89(345):531–541. [Google Scholar]

- Pikirayi I., Lindahl A. Ceramics, ethnohistory, and ethnography: locating meaning in southern African iron Age ceramic assemblages. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2013;30:455–473. [Google Scholar]

- Quellet J. Nyanga National Park: inside a house. 2014. https://www.jnomade.org/en/hiace-4/zimbabwe/nyanga/

- Randall-McIver D. McMillan; London: 1906. Medieval Rhodesia. [Google Scholar]

- Ranger T. Missionaries, migrants and the Manyika: the invention of ethnicity in Zimbabwe. In: Vail L., editor. The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. James Currey; London: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield J.F. South African Archaeological Society; Cape Town: 1948. Primitive Pottery, an Introduction to South African Ceramics, Prehistoric and Protohistoric. [Google Scholar]

- Shenjere P. University of Dar es Salaam; Tanzania: 2011. The Animal Economy of Prehistoric Farming Communities of Manicaland, Eastern Zimbabwe. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Skibo Ceramic style analysis in archaeology and ethnoarchaeology. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 1989;8(4):388–409. [Google Scholar]

- Skibo J.M. Plenum; New York: 1992. Pottery Function. [Google Scholar]

- Skibo J.M. Springer; New York: 2013. Understanding Pottery Function. [Google Scholar]

- Soper R. British Institute in East Africa; London: 2002. Nyanga: Ancient Fields, Settlements and Agricultural History in Zimbabwe. Memoirs of the British Institute in Eastern Africa: Number 16. [Google Scholar]

- Soper R., Chirawu S. Ruins on Mount Muozi, Nyanga district, Zimbabwe. Zimbabwean PreHistory. 1997;22:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl A.B. Has ethnoarchaeology come of Age? Antiquity. 1995;69(263):404–407. [Google Scholar]

- Stark M.T. Current issues in ceramic ethnoarchaeology. J. Archaeol. Res. 2003;11(3):193–242. [Google Scholar]

- Stead W.H. Notes on the types of clay pots found in the Inyanga District, 1945, identified from specimens collected for the purpose by native messengers at office of Native Commissioner, Inyanga. NADA. 1947;24:100–102. [Google Scholar]

- Summers R. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1958. Inyanga: Prehistoric settlements in Southern Rhodesia. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton J.,E.,G. Irrigation and soil conservation in African agricultural history. J. Afr. Hist. 1984;25:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Theal G.M. 1–9. Facsimile reprint; Cape Town: 1898–1903. (Records of South-Eastern Africa). [Google Scholar]

- Thebe P.C., Sadr K. Forming and shaping pottery boundaries in contemporary south eastern Botswana. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2017;34:75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wild H. Inyanga: Prehistoric settlements in Southern Rhodesia. Summers, R. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1958. Botanical notes relating to the Van Niekerk Ruins. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne-Jones S., Mapunda B. ‘This is what pots look like here’: ceramics, tradition and consumption on Mafia Island, Tanzania. Azania: Archaeol. Res. Afr. 2008;43(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 19941996.Bent J.T. The ruined cities of Mashonaland. Routledge; London: 1892. [Google Scholar]

- 19941997.Brand W. Further observations on the pit ruin M4, Mkondwe farm, Penhalonga, Rhodesia. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 1970;25:59–64. doi: 10.2307/3887950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19941998.Henrickson R.C., Mcdonald M.A. Ceramics form and function. An ethnographic search and an archaeological application. Am. Anthropol. 1983;85:640–643. doi: 10.1525/aa.1983.85.3.02a00070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19941999.Appadurai A. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 19942000.Gosselain O. To Hell with Ethnoarchaeology. Archaeol. Dialogues. 2016;23(2):215–228. [Google Scholar]

- 19942001.Karega-Munene, Schmidt P. Postcolonial archaeologies in Africa: breaking the silence. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2010;27:323–337. [Google Scholar]

- 19942002.Burke E.E. The Journals of Carl Mauch His travels in the Transvaal and Rhodesia 1869-1872. National Archives of Rhodesia; Salisbury: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 19942003.Bullock C. The Mashona. Juta; Cape Town: 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 19942004.Lyons D., Freeman A. Im not evil: Materialising identities of marginalised potters in Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Azania Archaeol. Res. Afr. 2009;44(1):75–93. [Google Scholar]

- 19942005.Wayessa B.S. The technical style of wallaga pottery making: an ethnoarchaeological study of oromo potters in southwest highland Ethiopia. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2011;28(4):301–326. [Google Scholar]

- 19942006.Galloway A. A report on the skeletal remains from the pit circles, Penhalonga, Southern Rhodesia. South Afr. J. Sci. 1937;33:1044. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement