Abstract

The craniocervical junction (CCJ) is a complex and unique osteoligamentous structure that balances maximum stability and protection of vital neurovascular anatomy with ample mobility and range of motion. With the increasing utilization and improved resolution of cervical magnetic resonance imaging, craniocervical injury is being more accurately defined as a spectrum of injury that ranges in severity from overt craniocervical disassociation to isolated injuries of one more of the craniocervical ligaments, which may also lead to craniocervical instability. Thus, it is vital for the radiologist and neurosurgeon to have a thorough understanding of the imaging anatomy and function of the CCJ.

Keywords: Craniocervical junction, magnetic resonance imaging, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Craniocervical disassociation (CCD) is a rare injury resulting from a significant hyperflexion-hyperextension force applied to the craniocervical junction (CCJ).[1] The CCJ is a unique osteoligamentous complex that includes the occipital condyles, C1–C2, and several major and minor stabilizing ligaments between the skull base and upper cervical spine [Figures 1-3]. Biomechanically, the CCJ balances the need for maximum stability and protection of vital neurovascular structures (brainstem, upper cervical cord, and vertebral arteries) while maintaining ample mobility to allow neck flexion, extension, rotation, and lateral bending. CCD results when there is a closed capitation injury in which the occipital condylar-C1 joint space and surrounding stabilizing ligaments are disrupted. Computed tomography (CT) is the modality of choice to evaluate for CCJ trauma since it readily depicts bony fractures and condylar-C1 joint subluxation and dislocation.[2,3,4] However, CT poorly depicts soft-tissue injuries and does not directly evaluate the major stabilizing ligaments of the CCJ. Thus, in the absence of bony trauma or abnormal joint space widening at the CCJ, CT may underreport craniocervical injury (CCI).[5] This situation may have devastating clinical consequences since early diagnosis of CCD and spinal stabilization protect against worsening spinal cord injury and reduce the likelihood of neurologic deterioration.[6,7]

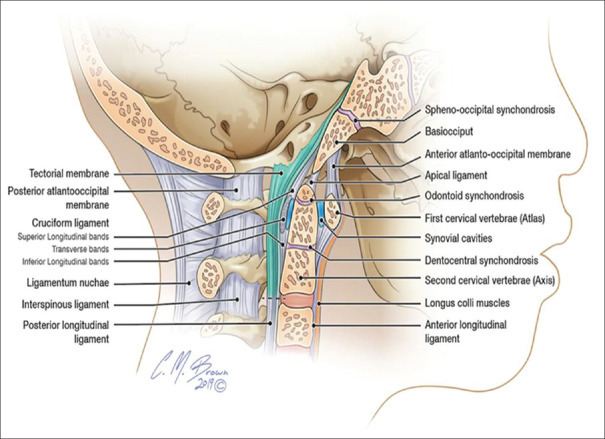

Figure 1.

Sagittal illustration demonstrating the major craniocervical ligaments, including the tectorial membrane (blue), anterior atlanto-occipital membrane, apical ligament, cruciform ligament (superior and inferior longitudinal bands and transverse bands), and posterior atlanto-occipital membrane and their relationship with surrounding ligaments, skull base, and bony anatomy of the cervical spine

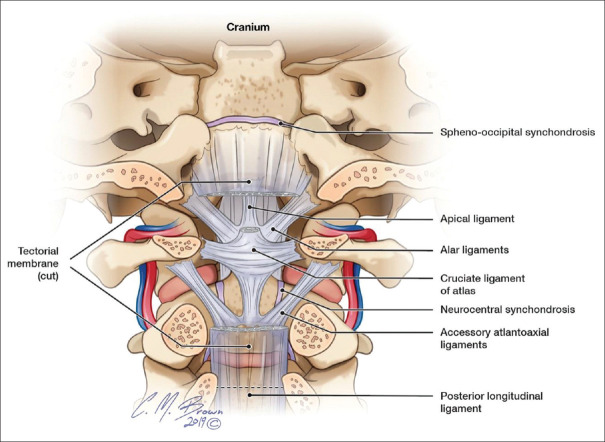

Figure 3.

Coronal, anterior illustration demonstrating the ligaments of the craniocervical junction including the tectorial membrane (cut), cruciate ligament, alar ligament, apical ligament, and posterior longitudinal ligament

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine is an increasingly utilized modality to evaluate for cervical cord and ligamentous injury since it allows direct inspection of the cord and stabilizing ligaments of the CCJ. In addition, the increasing use of cervical MRI is allowing a deeper understanding of CCI as a spectrum of injury, ranging in severity from frank CCD with condylar-C1 dislocation to more subtle isolated injuries to one or more of the craniocervical ligaments (which may or may not result in craniocervical instability).[8,9] The radiologist and neurosurgeon, therefore, need to have a thorough understanding of the anatomy, function, and imaging appearance of the ligaments of the CCJ on MRI to properly diagnose the extent of CCI and properly triage the patient. Thus, we present a comprehensive overview of the ligamentous structures between the skull base and C1–C2 including a discussion of the anatomic, functional, and MRI appearance of these structures.

SUPERFICIAL ANTERIOR ATLANTO-OCCIPITAL LIGAMENT

The superficial anterior atlanto-occipital ligament (SAAOL) is the most anterior CCJ ligament and is infrequently described in the literature.[10] Older anatomic texts and one recent cadaveric study of ten patients describe the SAAOL as a thin, midline ligament running anterior to the anterior atlanto-occipital membrane (AAOM) running between the basion of the clivus and anterior tubercle of C1. The ligament becomes taut with hyperextension and lax with hyperflexion with a relatively low tensile strength compared with the alar and transverse ligaments. Thus, the SAAOL likely plays a minor role in preventing hyperextension injury in the setting of CCJ trauma.[11] To our knowledge, no description of the SAAOL on MRI exists, which may be related to the difficulty in visualizing this ligament separate from the AAOM or from the absence of routine coronal plane imaging with standard cervical MRI trauma protocols. On coronal plane imaging, the SAAOL can be visualized on CT and MRI as a thin, midline cord-like ligament that extends from the basion to the anterior tubercle of C1. It is located posterior to the longus capitis muscle and just anterior to the AAOM.

ANTERIOR ATLANTO-OCCIPITAL MEMBRANE

The AAOM is a densely woven, broad ligament that fans out bilaterally from the midline and runs from the anterior margin of the caudal clivus and inserts on the anterior arch of C1. It is located immediately posterior to the longus capitis muscle and SAAOL and forms the anterior boundary of the supradental space. Biomechanically, the AAOM helps to prevent hyperextension of the CCJ and is thought to play a nominal role in CCJ stability.[12] The AAOM is best depicted on MRI on sagittal and coronal imaging as fan-shaped ligament extending out from midline along the anterior arch of C1 to attach to the anterior clivus [Figure 4].

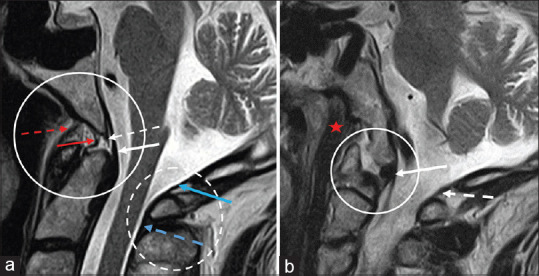

Figure 4.

(a) Sagittal, midline T2 weighted image of the cervical spine demonstrating the anterior atlanto-occipital membrane (red dashed arrow), apical ligament (red arrow), superior longitudinal band of the cruciform ligament (white dashed arrow), tectorial membrane (white arrow), and posterior atlanto-occipital membrane complex, including the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane (blue arrow) and posterior atlanto-axial membrane (blue dashed arrow). (b) Parasagittal T2 weighted image of the cervical spine demonstrating the longus capitis muscle (red star) inserting on the skull base, the alar ligament (white arrow) inserting on the occipital condyle, and the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane (white dashed arrow). Clinical images were obtained from imaging studies performed at our institution. No patient identifying information was included

ATLANTO-OCCIPITAL CAPSULAR LIGAMENT

The bony articulation between the occipital condyles and lateral masses of C1 constitutes the condylar-C1 joint. This joint is a synovial joint comprised of the convex articular surface of the bilateral occipital condyle with the concave articular surfaces of the lateral masses of C1. The morphology of the joint is analogous to a teacup resting on a saucer. It allows approximately 25° of flexion/extension and 5° of rotation.[13] The entire joint space is enveloped by a tough capsular ligament that spans the joint space and reinforces the joint. It maintains a significant contribution to CCJ stability.[14] On CT and MRI, the joint space should measure <2 mm and appear symmetric with the contralateral side. Abnormal joint space widening, subluxation, or frank dislocation of the condylar-C1 joint implies underlying injury to the capsular ligament and significant CCI, if not frank CCD.

APICAL LIGAMENT

The apical ligament is a thin, midline ligament running in the supradental recess between the basion of the foramen magnum and the atlantoaxial joint space or bony tip of the dens. It is separated anteriorly from the AAOM and posteriorly from the superior band of the cruciform ligament by fat and connective tissue. It is considered a vestigial structure, representing a tiny notochordal remnant with surrounding elastic fibers and behaves analogous to a rudimentary nucleus pulposus between the basion and C2. The apical ligament does not contribute significantly to craniocervical stability and may be absent in up to 20% of people.[15,16] On MRI, the ligament appears as a thin, midline T2 hypointense band extending between the basion and tip of the dens or anterior atlantoaxial joint space. It is outlined by a small fat pad in the supradental recess [Figure 4].

CRUCIFORM LIGAMENT

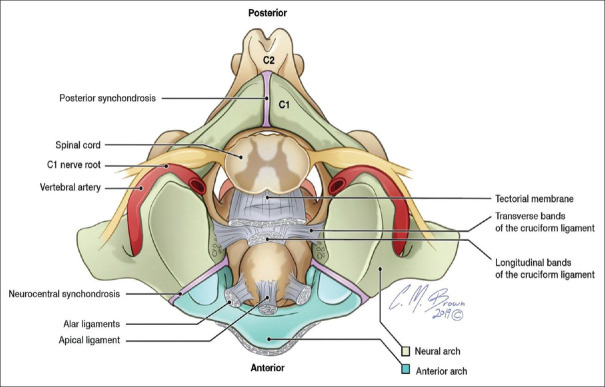

The cruciform ligament is a cross-shaped ligament-centered posterior to the dens that consists of a superior and inferior longitudinal band and a bilateral transverse band [Figures 1-3]. This ligament holds the C2 dens in close proximity with the anterior arch of C1, thus maintaining the integrity of the atlantoaxial joint space.[17] The superior longitudinal band ascends from the center of the ligament between the apical ligament anteriorly and the tectorial membrane (TM) posteriorly to insert on the basion of the foramen magnum. The inferior longitudinal band descends from the center of the ligament to insert on the posterior body of C2. The transverse band of the cruciform ligament fans out laterally on either side of the posterior dens to insert on the inner bony protuberance of the anterolateral C1 arch. A small bursa is located anterior to the transverse band of the cruciate ligament and posterior to the dens. The transverse band plays a vital role in maintaining C1–C2 stability and the atlantoaxial joint, while the superior longitudinal band plays a nominal role in craniocervical stability.[18]

On CT, an injury to the transverse band of the cruciform ligament is implied by abnormal widening of the atlantoaxial joint space (typically >2.5 mm in adults measured between the anterior inferior C1 arch and dens).[19] On MRI, the superior and inferior longitudinal bands are often not visualized separately from the TM. The transverse band of the cruciform ligament is best visualized on coronal and axial imaging as a T2 hypointense band fanning out laterally posterior to the dens and inserting on the inner surface of the lateral C1 arch [Figure 5].

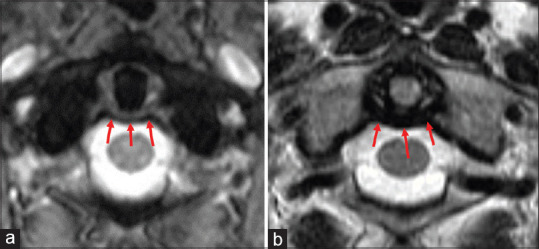

Figure 5.

Axial T2 medic (a) and T2 weighted sequence (b) through C1-C2 level demonstrating the transverse band of the cruciform ligament (red arrows) coursing posterior to the dens and inserting on the inner cortex of the anterolateral C1 arch. The cruciform ligament is the major stabilizing ligament of the atlantoaxial joint. Clinical images were obtained from imaging studies performed at our institution. No patient identifying information was included

TECTORIAL MEMBRANE

The TM is a 1 mm thick, superiorly directed extension of the posterior longitudinal ligament located posterior to the C2 vertebral body and dens [Figures 1 and 3]. Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that the superior extension of the TM firmly adheres to the dura mater posterior to the clivus.[20] The inferior extension of the TM attaches firmly to the C2 body, thus forming a sling posterior to the dens. Thus, the TM helps to prevent ventral cord impingement with neck flexion. Biomechanically, the TM is one of the major stabilizing ligaments of the CCJ and the only ligament with a dural attachment.[21]

Although the TM is not directly visualized on CT, an injury to the TM in the pediatric population may present on head CT with a characteristic retroclival epidural hematoma related to the TM stripping off the retroclival dura and tearing the basilar venous plexus. On MRI, the TM is a thin, T2 hypointense ligament located posterior to the dens and C2 body and inserting on posterior clivus. Recently, TM tears on MRI have been divided by Fiester et al. into four types based on the imaging appearance: Type 1 – retroclival stripping injury (more common in pediatric patients); Type 2a – subclival disruption at the basion and type 2b – subclival disruption at the odontoid (both more common in adult patients); and Type 3 – thinning or stretch injury of the TM.[22]

ALAR LIGAMENTS

The alar ligaments are paired ligaments that extend from the superolateral dens to the medial surface of the occipital condyles [Figures 2 and 3]. The alar ligaments are major stabilizers of the CCJ and help hold the dens upright and in close conjunction with the skull base and anterior C1 arch. The alar ligaments are not directly visualized on CT; however, an alar ligament injury may be implied in the setting of an avulsive fracture of the medial occipital condyle (Type 3 condylar fracture) or superolateral dens. An avulsive fracture in these locations on CT often requires a cervical MRI to evaluate the remaining ligaments of the CCJ. On MRI, the alar ligaments can be directly visualized on axial, coronal, and sagittal imaging and appear as a thin hypointense T2 band extending from the superolateral dens to the medial surface of the occipital condyles [Figure 4].

Figure 2.

Axial illustration demonstrating the deep ligaments of the craniocervical junction, including the tectorial membrane (cut), transverse band of the cruciate ligament, and alar ligaments and their anatomic relationship with the brainstem and vertebral arteries

POSTERIOR ATLANTO-OCCIPITAL MEMBRANE

The posterior atlanto-occipital membrane (PAOM) is a broad, fan-shaped midline ligament that runs between the posterior C1 arch and the posterior margin of the foramen magnum [Figure 1]. It is the superior extension of the ligamentum flavum at the C1 level. Prior cadaveric studies have suggested that the superior extension of the membrane fuses directly with occipital dura similar to the tectorial membrane with the retroclival dura.[23,24] On each side of the membrane, it fuses laterally with the atlanto-occipital joint capsules where a small defect is present that allows the passage of the vertebral artery and suboccipital nerve. Medially, the fibers of the PAOM are slightly thicker where the ligament runs between the posterior tubercle of C1 to the opisthion of the foramen magnum. On MRI, the PAOM is best visualized on sagittal imaging as a broad, but thin, V-shaped ligament that runs between the posterior C1 arch and the posterior lip of the foramen magnum that continues seamlessly as the ligamemtum flavum inferior to C1. The PAOM helps to prevent hyperflexion and impingement of the atlas on the cervicomedullary junction and likely plays a major role in stabilizing the posterior CCJ[25] [Figure 1].

ACCESSORY CRANIOCERVICAL JUNCTION LIGAMENTS

More recently, cadaveric studies have demonstrated that there are several smaller craniocervical ligaments that have an inconsistent presence. For instance, the anterior atlantodental ligament is a small midline ligament in the atlantoaxial joint space that extends between the anterior dens to the posterior margin of the anterior C1 arch.[26] The transverse occipital ligament is a thin ligament that runs laterally between the occipital condyles and has variable attachments with the alar ligaments and dens in the midline.[27] These ligaments are not directly visualized on MRI and their contributions to craniocervical stability are still being investigated.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kasliwal MK, Fontes RB, Traynelis VC. Occipitocervical dissociation-incidence, evaluation, and treatment. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016;9:247–54. doi: 10.1007/s12178-016-9347-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith P, Linscott LL, Vadivelu S, Zhang B, Leach JL. Normal development and measurements of the occipital condyle-C1 interval in children and young adults. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:952–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pang D, Nemzek WR, Zovickian J. Atlanto-occipital dislocation--part 2: The clinical use of (occipital) condyle-C1 interval, comparison with other diagnostic methods, and the manifestation, management, and outcome of atlanto-occipital dislocation in children. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:995–1015. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303196.87672.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gire JD, Roberto RF, Bobinski M, Klineberg EO, Johnson BD. The utility and accuracy of computed tomography in the diagnosis of occipitocervical dissociation. Spine J. 2013;13:510–19. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwong Y, Rao N, Latief K. Craniometric measurements in the assessment of craniovertebral settling: Are they still relevant in the age of cross-sectional imaging? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W421–5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellabarba C, Mirza SK, West GA, Mann FA, Dailey AT, Newell DW, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of craniocervical dislocation in a series of 17 consecutive survivors during an 8-year period. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:429–40. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.6.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadley MN, Walters BC, Grabb PA, Oyesiku NM, Przybylski GJ, Resnick DK, et al. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries. Clin Neurosurg. 2002;49:407–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siddiqui J, Grover PJ, Makalanda HL, Campion T, Bull J, Adams A. The spectrum of traumatic injuries at the craniocervical junction: A review of imaging findings and management. Emerg Radiol. 2017;24:377–85. doi: 10.1007/s10140-017-1490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deliganis AV, Baxter AB, Hanson JA, Fisher DJ, Cohen WA, Wilson AJ, et al. Radiologic spectrum of craniocervical distraction injuries. Radiographics. 2000;2:S237–50. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.suppl_1.g00oc23s237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikuta S, Iwanaga J, Watanabe K, Tubbs RS. Superficial anterior atlanto-occipital ligament: Anatomy of a forgotten structure with relevance to craniocervical stability. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2019;10:42–5. doi: 10.4103/jcvjs.JCVJS_110_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nidecker AE, Shen PY. Magnetic resonance imaging of the craniovertebral junction ligaments: Normal anatomy and traumatic injury. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2016;77:388–95. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riascos R, Bonfante E, Cotes C, Guirguis M, Hakimelahi R, West C. Imaging of atlanto-occipital and atlantoaxial traumatic injuries: What the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:2121–34. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015150035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tubbs RS, Hallock JD, Radcliff V, Naftel RP, Mortazavi M, Shoja MM, et al. Ligaments of the craniocervical junction. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14:697–709. doi: 10.3171/2011.1.SPINE10612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Offiah CE, Day E. The craniocervical junction: Embryology, anatomy, biomechanics and imaging in blunt trauma. Insights Imaging. 2017;8:29–47. doi: 10.1007/s13244-016-0530-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dundamadappa SK, Cauley KA. MR imaging of acute cervical spinal ligamentous and soft tissue trauma. Emerg Radiol. 2012;19:277–86. doi: 10.1007/s10140-012-1033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menezes AH, Traynelis VC. Anatomy and biomechanics of normal craniovertebral junction (a) and biomechanics of stabilization (b) Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24:1091–100. doi: 10.1007/s00381-008-0606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulbrich EJ, Eigenheer S, Boesch C, Hodler J, Busato A, Schraner C, et al. Alterations of the transverse ligament: an MRI study comparing patients with acute whiplash and matched control subjects. Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:961–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dvorak J, Schneider E, Saldinger P, Rahn B. Biomechanics of the craniocervical region: The alar and transverse ligaments. J Orthop Res. 1988;6:452–61. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100060317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rojas CA, Hayes A, Bertozzi JC, Guidi C, Martinez CR. Evaluation of the C1-C2 articulation on MDCT in healthy children and young adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1388–92. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tubbs RS, Kelly DR, Humphrey ER, Chua GD, Shoja MM, Salter EG, et al. The tectorial membrane: Anatomical, biomechanical, and histological analysis. Clin Anat. 2007;20:382–6. doi: 10.1002/ca.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meoded A, Singhi S, Poretti A, Eran A, Tekes A, Huisman TA. Tectorial membrane injury: frequently overlooked in pediatric traumatic head injury. Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:1806–11. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiester P, Soule E, Natter P, Rao D. Tectorial membrane injury in adult and pediatric trauma patients: A retrospective review and proposed classification scheme. Emerg Radiol. 2019;26:615–22. doi: 10.1007/s10140-019-01710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tubbs RS, Wellons JC, 3rd, Blount JP, Oakes WJ. Posterior atlantooccipital membrane for duraplasty. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:266–8. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.97.2.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nash L, Nicholson H, Lee AS, Johnson GM, Zhang M. Configuration of the connective tissue in the posterior atlanto-occipital interspace: A sheet plastination and confocal microscopy study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1359–66. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166159.31329.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krakenes J, Kaale BR, Moen G, Nordli H, Gilhus NE, Rorvik J. MRI of the tectorial and posterior atlanto-occipital membranes in the late stage of whiplash injury. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:585–91. doi: 10.1007/s00234-003-1036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tubbs RS, Mortazavi MM, Louis RG, Loukas M, Shoja MM, Chern JJ, et al. The anterior atlantodental ligament: Its anatomy and potential functional significance. World Neurosurg. 2012;77:775–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tubbs RS, Griessenauer CJ, McDaniel JG, Burns AM, Kumbla A, Cohen-Gadol AA. The transverse occipital ligament: Anatomy and potential functional significance. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:1–3. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000349213.09505.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]