Abstract

The incidence of intramedullary spinal cord metastasis (ISCM) has been increasing because the overall survival of patients with cancer has improved thanks to recent advanced therapies, such as molecular targeted drugs, anticancer agents, and various irradiation techniques. ISCM from lung and breast cancer is the most common form among cases of ISCM. We report an extremely rare form of ISCM from gastric cancer. This 83-year-old man who had a past medical history of gastric adenocarcinoma presented with acute onset of paraparesis. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging revealed an intramedullary lesion at the upper thoracic level. Due to rapid worsening of his paresis, we decided to perform tumor extirpation. Gross total resection of the tumor was successfully performed. Pathological examination revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, suggesting the diagnosis of ISCM from gastric cancer. He demonstrated gradual improvement of paraparesis soon after surgery, although his overall survival was limited to about 6 months after surgery. When examining the etiology of acute paraparesis in elderly patients with a past medical history of cancer, ISCM should be considered in the differential diagnosis. The prognosis of ISCM from gastric cancer is still extremely limited. Unfortunately, there is currently no treatment with proven efficacy. Surgery for ISCM from gastric cancer, although a challenging procedure for spine surgeons, should be considered as a therapeutic option in these patients.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, gastric cancer, intramedullary metastasis, paraparesis, spinal cord

INTRODUCTION

Although intramedullary spinal cord metastasis (ISCM) is rare, the incidence of ISCM has been recently increasing because of improvement in overall survival of cancer patients thanks to recent advanced therapies, such as molecular targeted drugs, anticancer agents, and various irradiation techniques.[1] In most cases of ISCM, lung and breast carcinomas are the common primary cancers,[2] and ISCM from gastric carcinoma has only rarely been reported in the literature. Due to the difficulty in radiological diagnosis, the extremely low frequency of treated cases and poor prognosis, the optimal treatment strategy for ISCM from gastric cancer has not been established, although palliative treatment with steroid administration, radiation therapy, or surgery might be viable options.[1,3,4] Here, we describe a case of ISCM from gastric adenocarcinoma presenting with acute onset of progressive paraparesis that was treated surgically. The prognosis of ISCM from gastric cancer is still extremely limited. Unfortunately, there is currently no therapy with proven efficacy in these cases.

CASE REPORT

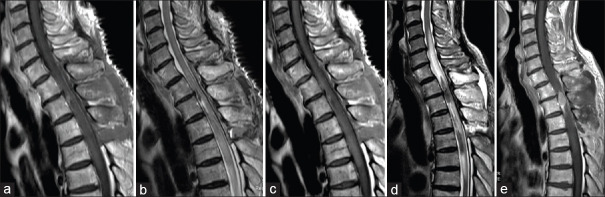

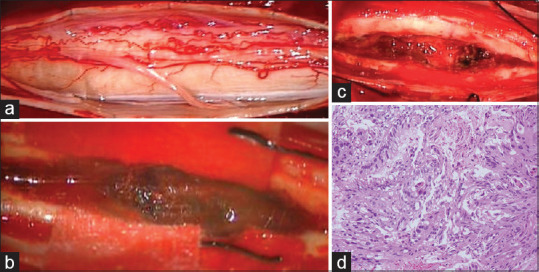

An 83-year-old man presented with acute onset of gait disturbance. He had a past medical history of partial gastrectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer 3 years before this admission to our institution. His performance score (PS) according to the Karnofsky PS had been maintained at about 90 after the gastric cancer treatment. Neurological evaluation at his current admission indicated sensory loss at the T3 level with grade 3/5 paraparesis. Bladder and rectal dysfunction was also detected. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an intramedullary mass lesion at the upper thoracic level. The intramedullary lesion showed relative hyperintensity on T1-weighted images [Figure 1a] and hypointensity on T2-weighted images, along with long-axis syringomyelia [Figure 1b and c]. The mass lesion showed homogenous contrast enhancement on T1-weighted images [Figure 1d]. His paraparesis showed rapid deterioration from grade 3/5 to grade 1/5 at 3 days after admission. After careful discussion, he finally decided to undergo surgical removal of the intramedullary tumor. Operative exposure revealed extensive swelling of the spinal cord itself [Figure 2a]. Myelotomy via a dorsal midline approach revealed a grayish-red tumor [Figure 2b]. Gross total resection was successfully performed in a piecemeal fashion [Figure 2c]. Pathological diagnosis after surgery suggested poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma secondary to gastric cancer [Figure 2d]. Fortunately, he showed a gradual improvement of paraparesis and he could walk with assistance. MRI obtained 1 week after surgery demonstrated no apparent lesion enhancement, with diminution of syringomyelia [Figure 3a-c]. Although local radiation therapy of the spinal cord was highly recommended, he refused adjuvant therapy. During subsequent postoperative follow-up, the patient presented again with paraparesis with neurological deterioration from grade 3/5 to grade 1/5. MRI performed 1.5 months after the primary surgery demonstrated local recurrence of the intramedullary tumor [Figure 3d and e]. He opted for palliative supportive care and died 6 months after the primary surgery.

Figure 1.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. The intramedullary lesion showing relative hyperintensity on T1-weighted magnetic resonance images (a) and hypointensity on T2-weighted magnetic resonance images accompanying the long-axis syringomyelia (b and c). The mass lesion showed homogenous contrast enhancement on T1-weighted images (d)

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photographs. Operative exposure showing extensive swelling of the spinal cord itself (a). Myelotomy via a dorsal midline approach showed presence of a grayish-red tumor (b). Gross total resection was successfully performed in a piecemeal fashion (c). Pathological diagnosis after surgery suggested poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma secondary to gastric cancer (H and E, ×400) (d)

Figure 3.

Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance images obtained 1 week after surgery showed no apparent lesion enhancement, with diminution of syringomyelia (a-c). Magnetic resonance images obtained 1.5 months after surgery showed local recurrence of the intramedullary tumor (d and e)

DISCUSSION

ISCM is recognized clinically in about 0.1%–0.4% of all patients with cancer and accounts for about 1%–3% of intramedullary spinal cord neoplasms.[5] The most common primary lesion leading to ISCM is lung cancer in 54%, followed by breast cancer in 13%, melanoma in 9%, lymphoma in 5%, and renal cell carcinoma in 4% of cases.[6] ISCM is usually seen in the cervical and thoracic regions.[1,6] Brown-Sequard syndrome or asymmetric myelopathy might be a common form of clinical presentation.[6] The neurological manifestations often progress very rapidly, and it has been suggested that 75% of ISCM cases might develop complete paraparesis within a month from the diagnosis.[3] Since ISCM is typically recognized in the later stage of cancer treatment, the prognosis of patients with ICSM is usually extremely poor and median survival time is reported as 3–4 months on average.[2,3,6]

ISCM from gastric cancer is an extremely rare form of ISCM, and only six such cases, including our case, have been reported in the literature [Table 1].[7,8,9,10,11] The reported patients were predominantly male (five males and one female) and middle aged, except our case. Although ISCM from gastric cancer can be found both during and after the course of treatment of gastric cancer, the neurological symptoms of ISCM preceded the clinical condition in only 1 case. In half of the reported cases, other metastatic lesions were recognized. With regard to the location of the metastatic spinal lesion, the cervical region was involved in three cases, thoracic in two cases, and lumbosacral in one case. Worsening of neurological symptoms occurred very rapidly, ranging from 3 days to 2 months. All patients except one underwent tumor extirpation. Only one patient received adjuvant therapy using radiation. The prognosis was very poor and most patients died within 6 months after the operation. The clinical characteristics of ISCM from gastric cancer appear to be much worse compared to those from other malignant tumors.

Table 1.

Literature review of ISCM from gastric cancer

| Author (year) | Age/Sex | Interval between cancer treatment and occurrence of ISCM | Other metastatic lesions | Timing of worsening neurological symptom | Location | Surgery | Surgical complication | Adjuvant therapy | Recurrence of ISCM | Survival after surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taniura et al. (2000)10 | 51/F | ISCM was the initial symptom | Brain | 2 months | C1-2 | Extirpation | None | None | None | 2 weeks |

| Gazzeri et al. (2006)8 | 68/M | 9 months | None | 1 month | C3-5 | Extirpation | None | None | None | 6 months |

| Cemil et al. (2012)7 | 48/M | 5 years | Rectum | 1 week | Th5-7 | Extirpation | None | Radiation therapy | None | ND |

| Hoover et al. (2012)11 | 60/M | ND | ND | ND | Lumbosacral | Biopsy | None | ND | ND | ND(dead) |

| Perez-Suarez et al. (2015)9 | 61/M | 3 years | None | 10 days | C6-7 | Extirpation | None | None | None | 6 months |

| Present case | 83/M | 3 years | Liver | 3 days | Th1-3 | Extirpation | None | None | + (1.5 months after surgery) | 6 months |

ISCM: intramedullary spinal cord metastasis, ND: not determined

The main goal in treating ISCM is to stop the acute worsening of neurological function despite limitation of the patient's life expectancy. Due to the small number of treated cases, there is still no consensus regarding the treatment of ISCM.[2] Therapeutic options include steroid administration, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgical extirpation, with radiation therapy and steroid administration probably being selected most often.[12] However, there is controversy regarding the effect or risk of radiation therapy because the maximum permissible radiation dose for the spinal cord is limited.[12,13] Chemotherapy might not be effective because of the existence of the blood–spinal barrier in the spinal cord.[4] When patients with ISCM show rapid and severe deterioration of neurological deficits, surgical treatment should be considered as one of the treatment options for the purpose of decompression of the spinal cord and confirmation of histopathological diagnosis.[12] Harada et al.[14] reported a favorable prognosis in patients with brain metastasis from gastric cancer treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Stereotactic radiosurgery, if available, might be suitable as adjuvant therapy for ISCM from gastric cancer. Recently, cancer immunotherapy, such as nivolumab, an anti-programmed cell death-1 antibody, has been approved for limited cancers, including gastric cancer.[15] The efficacy of nivolumab for brain metastasis from melanoma, lung, and gastric cancer has also been reported.[16,17,18,19] Hence, although nivolumab might be effective for ISCM, there is only one report of the efficacy of nivolumab for ISCM. Phillips et al. reported a case of ISCM from lung cancer treated with nivolumab.[20] Takao et al. treated advanced gastric cancer with metastatic lesions, including bone metastasis, with nivolumab, and reported that long-term stability of the cancer could be maintained when nivolumab treatment was initiated in a patient with good PS.[19] Ahn et al. reported the efficacy of combination of nivolumab and stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastasis from gastric cancer.[21] In the case presented here, surgical extirpation of ISCM was selected first because the patient showed a rapid deterioration of paraparesis. Since postoperative adjuvant treatment was not introduced in this case, local recurrence was finally recognized 1.5 months after surgery. Use of postoperative radiation therapy along with nivolumab should be assessed in future studies to determine their efficacy as adjuvant therapy in such cases.

CONCLUSIONS

When examining the etiology of acute paraparesis in elderly patients with a past medical history of cancer, ISCM should be considered in the differential diagnosis. The prognosis of ISCM from gastric cancer is still extremely limited. Unfortunately, there is currently no proven effective therapy. Surgery for ISCM from gastric cancer, although a challenging procedure for spine surgeons, should be considered as a therapeutic option in these patients.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Payer S, Mende KC, Westphal M, Eicker SO. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: An increasingly common diagnosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E15. doi: 10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, Li C, Dong L, Liu M. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: An institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741–53. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S193235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grem JL, Burgess J, Trump DL. Clinical features and natural history of intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. Cancer. 1985;56:2305–14. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851101)56:9<2305::aid-cncr2820560928>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalita O. Current insights into surgery for intramedullary spinal cord metastases: A literature review? Int J Surg Oncol. 2011;2011:989506. doi: 10.1155/2011/989506. doi: 10.1155/2011/ Epub 2011 May 26. PMID: 22312538; PMCID: PMC3263682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connolly ES, Jr, Winfree CJ, McCormick PC, Cruz M, Stein BM. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1996;46:329–37. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiff D, O'Neill BP. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: Clinical features and treatment outcome. Neurology. 1996;47:906–12. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cemil B, Gokce EC, Kirar F, Erdogan B, Bayrak R. Intramedullary spinal cord involvement from metastatic gastric carcinoma: A case report. Turk Neurosurg. 2012;22:496–8. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.3861-10.0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazzeri R, Galarza M, Faiola A, Gazzeri G. Pure intramedullary spinal cord metastasis secondary to gastric cancer. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:173–7. doi: 10.1007/s10143-005-0015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez-Suárez J, Barrio-Fernández P, Ibáñez-Plágaro FJ, Ribas-Ariño T, Calvo-Calleja P, Mostaza-Saavedra AL. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis from gastric adenocarcinoma: Case report and review of literature. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2016;27:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neucir.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taniura S, Tatebayashi K, Watanabe K, Watanabe T. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis from gastric cancer. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:145–7. doi: 10.3171/spi.2000.93.1.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoover JM, Krauss WE, Lanzino G. Intradural spinal metastases: A surgical series of 15 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012;154:871–7. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takami T, Naito K, Yamagata T, Ohata K. Surgical indication and limitaion of metastatic spine tumor. Jpn J Neurosurg. 2018;27:111–21. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashii H, Mizumoto M, Kanemoto A, Harada H, Asakura H, Hashimoto T, et al. Radiotherapy for patients with symptomatic intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. J Radiat Res. 2011;52:641–5. doi: 10.1269/jrr.10187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harada K, Hwang H, Wang X, Ahmed A, Masaaki I, Murphy MA, et al. Brain metastases in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer is associated with proximally located adenocarcinoma and lymph node metastases. Gastric Cancer. 2020;23:904–12. doi: 10.1007/s10120-020-01075-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, Ryu MH, Chao Y, Kato K, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2461–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Algazi A, Hamid O, Hodi FS, Moschos SJ, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in melanoma metastatic to the brain. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:722–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanier CM, Hughes R, Ahmed T, LeCompte M, Masters AH, Petty WJ, et al. Immunotherapy is associated with improved survival and decreased neurologic death after SRS for brain metastases from lung and melanoma primaries. Neurooncol Pract. 2019;6:402–9. doi: 10.1093/nop/npz004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamath SD, Kumthekar PU. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of central nervous system (CNS) metastatic disease. Front Oncol. 2018;8:414. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takao C, Matsuhashi N, Murase Y, Yasufuku I, Tanahashi T, Yamaguchi K, et al. Experience with nivolumab in the treatment of metastatic gastric cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2018;45:1546–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips KA, Gaughan E, Gru A, Schiff D. Regression of an intramedullary spinal cord metastasis with a checkpoint inhibitor: A case report. CNS Oncol. 2017;6:275–80. doi: 10.2217/cns-2017-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn MJ, Lee K, Lee KH, Kim JW, Kim IY, Bae WK. Combination of anti-PD-1 therapy and stereotactic radiosurgery for a gastric cancer patient with brain metastasis: A case report. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:173. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3906-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]