Abstract

Introduction:

Raising knowledge over cardiac complications and managing them can play a key role in their recovery. In this study, we aim to investigate the evidence regarding the prevalence of cardiac complications and the resulting mortality rate in COVID-19 patients.

Method:

Search was conducted in electronic databases of Medline (using PubMed), Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science, in addition to the manual search in preprint databases, and Google and Google scholar search engines, for articles published from 2019 until April 30th, 2020. Inclusion criterion was reviewing and reporting cardiac complications in patients with confirmed COVID-19.

Results:

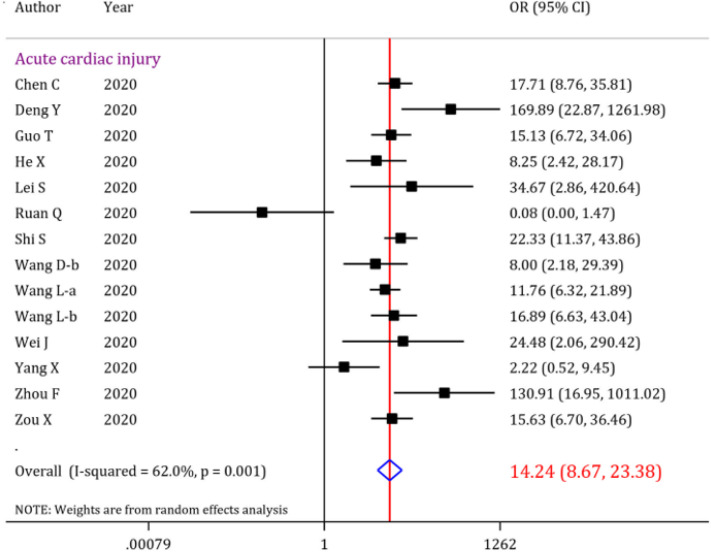

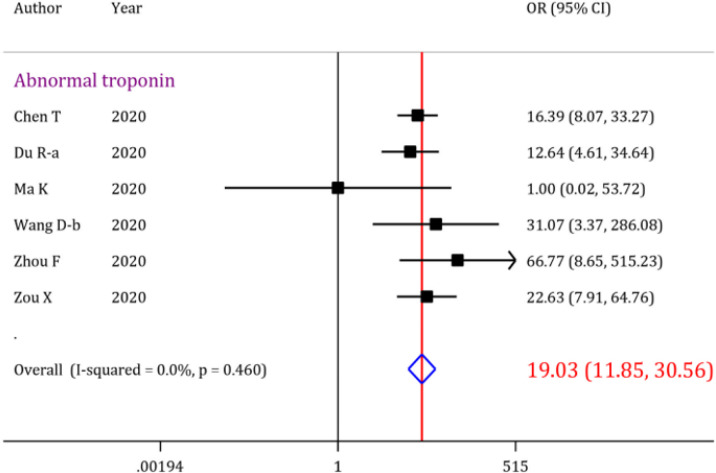

The initial search resulted in 853 records, out of which 40 articles were included. Overall analysis showed that the prevalence of acute cardiac injury, heart failure and cardiac arrest were 19.46% (95% CI: 18.23-20.72), 19.07% (95% CI: 15.38-23.04) and 3.44% (95% CI: 3.08-3.82), respectively. Moreover, abnormal serum troponin level was observed in 22.86% (95% CI: 21.19-24.56) of the COVID-19 patients. Further analysis revealed that the overall odds of mortality is 14.24 (95% CI: 8.67-23.38) times higher when patients develop acute cardiac injury. The pooled odds ratio of mortality when the analysis was limited to abnormal serum troponin level was 19.03 (95% CI: 11.85-30.56).

Conclusion:

Acute cardiac injury and abnormal serum troponin level were the most prevalent cardiac complications/abnormalities in COVID-19 patients. The importance of cardiac complications is emphasized due to the higher mortality rate among patients with these complications. Thus, troponin screenings and cardiac evaluations are recommended to be performed in routine patient assessments.

Key Words: COVID-19, Cardiovascular System, Heart Injuries, Hospital Mortality

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel coronavirus, which emerged in Wuhan, China in December 2019 and has spread to over 200 countries in the world, ever since (1). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mostly causes lower respiratory tract infection symptoms such as fever, which is its most prevalent symptom, cough, and dyspnea (2). Although people with severe type of the disease form the minority of the patients, it is illustrated that mortality rate is the highest among patients who have comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases (3).

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) has been shown to be the receptor of the virus in human cells. Since this enzyme is expressed in many organs such as lungs, heart, kidneys and brain, extrapulmonary manifestations and complications are being studied rigorously, all around the world (4). Cardiac involvement is one of the most common causes of death in COVID-19 patients (5). Cardiovascular complications, whether being chronic or acute, can lead to critically imbalanced homeostasis and could be a serious strike to patient’s recovery from the disease (6). Therefore, raising awareness over cardiac complications caused by the disease and managing them as early as possible can play a key role in recovery of the patients. However, there is no comprehensive evaluation of this issue. Therefore, in this study, we aim to investigate the evidence regarding the prevalence of cardiac complications in COVID-19 patients. Moreover, the risk of mortality after COVID-19 related cardiac involvement has also been assessed.

Methods

Study design

The present systematic review and meta-analysis aims to investigate the evidence regarding cardiac complications in patients, confirmed with COVID-19, and to see whether there is any potential association between the prevalence of cardiac complications and their mortality rate. As a result, PECO in the current study is defined as: P (patients): Patients with confirmed COVID-19 disease, E (exposure): SARS-CoV-2 infection, O (outcome): prevalence of cardiac complications and mortality after COVID-19 related cardiac involvement. As for comparison (C in PECO), mortality rate was compared between COVID-19 patients with cardiac complications and patients without any cardiac involvements.

Search strategy

The searching process was initiated by selecting keywords with the help of experts in the field and screening titles of similar articles. Then, using MeSH and Emtree, equivalent and related synonyms were identified. As a result, a search strategy was constructed based on the instructions of electronic databases of Medline, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science, and an extensive search was performed in each of the mentioned databases for articles published from the February 1st of 2019 until April 30th, 2020. The search strategy in Medline database through PubMed search engine is presented in Appendix 1. In addition, a search was performed in preprint databases, Google, and Google scholar to obtain preprinted and possibly missed manuscripts (gray litterateur search). Moreover, references of the obtained review articles were screened to find additional articles.

Appendix 1.

Medline search query

| Search terms |

|---|

|

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria in the present meta-analysis was reporting cardiac complications and cardiac related mortality rate in patients with confirmed COVID-19. Original observational studies were included. Since most COVID-19 studies had a retrospective nature, both retrospective and prospective studies were included. Prevalence of cardiac complications following COVID-19 and its pertaining mortality rate were extracted from cohort and cross-sectional studies. In addition, we added an extra aim to provide evidence on the relationship between cardiac complication occurrence in COVID-19 patients and their mortality. In this section, in addition to cohort and cross-sectional studies, case-control studies were also included. Furthermore, the exclusion criteria were case report studies, review articles, studies that did not report cardiac involvement and studies whose entire target population was patients with cardiac comorbidities as underlying disease.

Data collection

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts of the gathered articles. Then, full texts of the related articles were obtained and included articles were selected and entered the present systematic review and meta-analysis. Finally, a summary of the included studies was recorded using a checklist, consisting of following variables: first author’s name, publication year, country in which the study was conducted in, number of patients, study design, number of patients in which the cardiac complication was assessed in, mean/median age of the patients, number of males among the patients, type of cardiac complication along with its diagnostic method, number of the deceased in patients presenting with cardiac complication (if reported), and number of the deceased among patients without the cardiac complication of the included articles. If several types of cardiac complications were reported in the studies, the number of each cardiac involvement was recorded separately. Any disagreements within the process were resolved using a third reviewer’s opinion.

Outcome

The primary outcome of the present meta-analysis was the prevalence of cardiac complications in COVID-19 patients. Secondary outcome was the risk of mortality after COVID-19 related cardiac involvement. Our screening showed that most studies reported abnormal serum troponin level and acute cardiac injury, separately, as cardiac assessments/complications. Other reported cardiac complications were heart failure, cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrest, myocarditis, pericardial effusion, cardiac insufficiency, and myocardial infarction.

Quality assessment

Two independent reviewers scored the quality of the studies according to National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) quality assessment tool (7). This tool contains 14 items on study design, patient selection, sample size justification, analysis, timeframe between exposure and outcome, assessment of different level of exposure, validity and reliability of exposure and outcome assessment, blinding status, missing data management, and considering potential confounders in the analysis. Each reviewer independently assessed the articles and categorized each item as low risk, high risk, unclear risk of bias, cannot determine, or not applicable. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using STATA 14.0 statistical program. Analyses were performed in two parts. Initially, the cardiac complications reported in the articles were categorized into 9 subgroups: acute cardiac injury, abnormal serum troponin level, heart failure, cardiac arrest, myocarditis, cardiac insufficiency, pericardial effusion, myocardial infarction, and cardiomyopathy. The prevalence of each cardiac complication among the COVID-19 patients was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using the “metaprop_one” command performed on the total sample size and the number of patients presenting each complication in the included articles.

In the second part of the analysis, the association between the manifestation of cardiac complications/abnormalities and mortality rate was calculated and presented as an overall odds ratio (OR) with a 95% CI using the “metan” command performed on four groups of data: number of the deceased in patients with a cardiac complication, number of the alive in patients with the cardiac complication, number of the deceased in patients without the cardiac complication, number of the alive in patients without the cardiac complication. I2 test was performed to assess heterogeneity, and if the heterogeneity among data was considerable, random effect model was used to calculate 95% CI. Egger’s test was used to evaluate publication bias. Finally, a sensitivity analysis was performed to determine whether the results can be considered robust or not. Therefore, in the sensitivity analyses we excluded possible outlier studies.

Results

Study characteristics

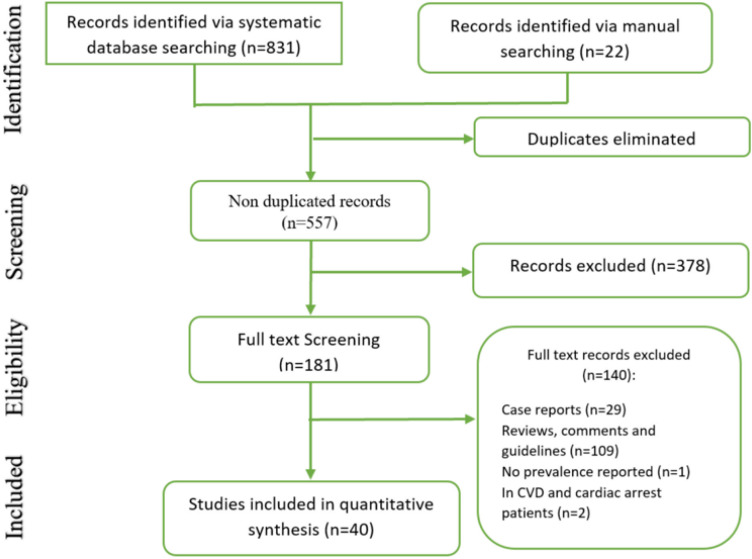

The systematic search resulted in 853 records, and after eliminating duplicates, 557 articles remained. Then, after screening titles and abstracts of the remaining articles, 181 studies were deemed potentially eligible. Afterwards, based on the mentioned exclusion and inclusion criteria, 40 articles were included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1) (5, 8-46). These 40 articles were treated as 60 different experiments, as some studies reported more than one cardiac complication/abnormality. Two studies had taken place in the United States (41, 45), one study was conducted in Spain (9), one study was carried out in Italy (42) and the rest of the included studies were conducted in China. Regarding the study design of the included articles, one study was ambispective (22), four studies were conducted prospectively (9, 14, 19, 39) and the other 35 studies were retrospective. Overall, 15616 patients with confirmed COVID-19 were enrolled in the included studies, with 2985 males among them [patients’ gender was not reported in two of the studies (42, 46)]; however, not all of the patients were assessed for each cardiac complication, so the total number of patients tested for each manifestation is presented for each complication in Table 1. In general, 9 different cardiac complications/abnormalities were reported in the studies including acute cardiac injury, which was reported in 26 studies (5, 8, 11, 13, 16, 18-20, 22-24, 26-30, 32, 33, 35, 37-41, 43, 46), abnormal serum troponin level, reported in 19 studies (8, 10-12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 25, 30, 32, 36-38, 40, 41, 43-45), heart failure, reported in four studies (8, 11, 32, 41), cardiac arrest, reported in three studies (5, 34, 42), myocarditis, reported in two studies (9, 44), cardiac insufficiency, reported in two studies (29, 30), pericardial effusion, reported in two studies (21, 31) and cardiomyopathy (45) and myocardial infarction (32), each reported in one study. Mortality rate was reported in 18 studies (8, 11, 13, 14, 16-18, 20, 26, 29, 30, 33, 34, 37, 39, 40, 44, 46). These numbers were further used to evaluate the odds ratio (OR) between the manifestation of each cardiac complication and the mortality rate in COVID-19 patients. Table 1 demonstrates a summary of the characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the present meta-analysis; CVD: Cardiovascular disease

Table 1.

Summary of the included studies

| Author; Year; Country | Study design | Total study population | Mean age | Number of males | Diagnostic methods | Type of cardiac complication | No. of patients tested for the complication | No. of patients with the complication | No. of deceased in patients with the complication | No. of deceased in patients without the complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal S; 2020; USA | Retrospective | 16 | 67 | 12 | Blood Sample, Echo | Acute cardiac injury | 16 | 3 | NR | NR |

| NR | Heart failure | 16 | 2 | NR | NR | |||||

| Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 16 | 10 | NR | NR | |||||

| Arentz M; 2020; USA | Retrospective | 21 | 70 | 11 | Blood Sample, Echo, Clinical | Cardiomyopathy | 21 | 7 | NR | NR |

| Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 21 | 3 | NR | NR | |||||

| Baldi E; 2020; Italy | Retrospective | 9806 | NR | NR | Hospital report | Cardiac arrest | 9806 | 362 | NR | NR |

| Barrasa H; 2020; Spain | Prospective | 48 | 63.2 | 27 | NR | Myocarditis | 48 | 1 | NR | NR |

| Chen C; 2020; China | Retrospective | 150 | 59 | 84 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 150 | 22 | NR | NR |

| Chen T; 2020; China | Retrospective | 274 | 62 | 171 | NR | Acute cardiac injury | 203 | 89 | 72 | 22 |

| NR | Heart failure | 176 | 43 | 41 | 42 | |||||

| Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 203 | 83 | 68 | 26 | |||||

| Deng Q; 2020; China | Retrospective | 112 | 65 | 57 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 112 | 42 | NR | NR |

| Deng Y; 2020; China | Retrospective | 225 | 54 | 124 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 225 | 66 | 65 | 44 |

| Du Ra; 2020; China | Prospective | 179 | 57.6 | 97 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 179 | 31 | 13 | 8 |

| Du Rb; 2020; China | Retrospective | 109 | 70.7 | 75 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 109 | 52 | NR | NR |

| Du Y; 2020; China | Retrospective | 85 | 65.8 | 62 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 85 | 38 | NR | NR |

| Clinical | Cardiac arrest | 85 | 7 | NR | NR | |||||

| Guo T; 2020; China | Retrospective | 187 | 58.5 | 91 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 187 | 52 | 31 | 12 |

| Han H; 2020; China | Retrospective | 273 | NR | 97 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 273 | 27 | 13 | 8 |

| He X; 2020; China | Retrospective | 54 | 68 | 34 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 54 | 24 | 18 | 8 |

| Hu L; 2020; China | Retrospective | 323 | 61 | 166 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 323 | 24 | NR | NR |

| Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 323 | 68 | NR | NR | |||||

| Huang C; 2020; China | Prospective | 41 | 49 | 30 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 41 | 5 | NR | NR |

| Acute cardiac injury | 41 | 5 | NR | NR | ||||||

| Lei S; 2020; China | Retrospective | 34 | 55 | 14 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 34 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Li K; 2020; China | Retrospective | 83 | 45.5 | 44 | CT | Pericardial effusion | 83 | 4 | NR | NR |

| Li X; 2020; China | Ambispective | 548 | 60 | 279 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 548 | 119 | NR | NR |

| Li Y; 2020; China | Retrospective | 54 | 61.8 | 34 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 41 | 23 | NR | NR |

| Liu M; 2020; China | Retrospective | 30 | 35 | 10 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 30 | 5 | NR | NR |

| Liu Y; 2020; China | Retrospective | 76 | 45 | 49 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 76 | 14 | NR | NR |

| Ma K; 2020; China | Retrospective | 84 | 48 | 48 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 84 | 36 | 0 | 0 |

| Blood Sample, Clinical Symptom | Myocarditis | 84 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ruan Q; 2020; China | Retrospective | 150 | NR | NR | NR | Acute cardiac injury | 68 | 5 | 5 | 63 |

| Shi S; 2020; China | Retrospective | 416 | 64 | 205 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 416 | 82 | 42 | 15 |

| Wan S; 2020; China | Retrospective | 135 | 47 | 72 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 135 | 10 | NR | NR |

| Wang Da; 2020; China | Retrospective | 138 | 56 | 75 | Blood Sample, ECG, Echo | Acute cardiac injury | 138 | 10 | NR | NR |

| Wang Db; 2020; China | Retrospective | 107 | 51 | 57 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 107 | 6 | 5 | 14 |

| Blood Sample, ECG, Echo | Acute cardiac injury | 12 | 8 | 19 | ||||||

| Wang La; 2020; China | Retrospective | 339 | 69 | 166 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 339 | 70 | 39 | 26 |

| Blood Sample, Clinical Symptom | Cardiac insufficiency | 339 | 58 | 25 | 52 | |||||

| Wang Lb; 2020; China | Retrospective | 202 | 63 | 88 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 202 | 27 | 17 | 14 |

| Blood Sample, ECG, Echo | Cardiac insufficiency | 202 | 24 | 14 | 19 | |||||

| Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 202 | 27 | NR | NR | |||||

| Wei J; 2020; China | Prospective | 101 | 49 | 54 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 101 | 16 | 3 | 0 |

| Xu X; 2020; China | Retrospective | 90 | 50 | 39 | CT | Pericardial effusion | 90 | 1 | NR | NR |

| Yang F; 2020; China | Retrospective | 92 | 69.8 | 49 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 92 | 31 | NR | NR |

| NR | Myocardial infarction | 92 | 6 | NR | NR | |||||

| NR | Heart failure | 92 | 2 | NR | NR | |||||

| Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 92 | 31 | NR | NR | |||||

| Yang X; 2020; China | Retrospective | 52 | 59.7 | 35 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 52 | 12 | 9 | 23 |

| Yao W; 2020; China | Retrospective | 202 | 63.4 | 136 | Clinical | Cardiac arrest | 202 | 4 | 0 | 21 |

| Zhang G; 2020; China | Retrospective | 221 | 55 | 108 | NR | Acute cardiac injury | 221 | 17 | NR | NR |

| Zhao X; 2020; China | Retrospective | 91 | 46 | 49 | Blood Sample | Acute cardiac injury | 91 | 14 | NR | NR |

| Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 88 | 3 | NR | NR | |||||

| Zheng Y; 2020; China | Retrospective | 99 | 49.4 | 51 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 99 | 88 | NR | NR |

| Zhou F; 2020; China | Retrospective | 191 | 56 | 119 | Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 145 | 24 | 23 | 31 |

| Heart failure | 145 | 44 | 28 | 26 | ||||||

| Acute cardiac injury | 145 | 33 | 32 | 22 | ||||||

| Zou X; 2020; China | Retrospective | 178 | 60.68 | 67 | Blood Sample, ECG, Echo | Acute cardiac injury | 154 | 45 | 34 | 18 |

| Blood Sample | Abnormal Troponin | 154 | 33 | 28 | 24 |

CT: Computed tomography scan; Echo: Echocardiography; ECG: Electrocardiography; NR: Not reported

Risk of bias assessment

No study had provided a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates. In addition, 39 studies were not measured to have key potential confounders in their assessment of outcomes. 10 studies did not report the details of their inclusion and exclusion criteria. Moreover, the participation rate of eligible persons was not reported in 6 studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies

| Author; Year | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | Item 11 | Item 12 | Item 13 | Item 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal S; 2020 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Arentz M; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Baldi E; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Barrasa H; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Chen C; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Chen T; 2020 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Deng Q; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Deng Y; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Du Ra; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Du Rb; 2020 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Du Y; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Guo T; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Han H; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| He X; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Huang C; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Hu L; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Lei S; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Li K; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Liu M; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Liu Y; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Li X; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Li Y; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Ma K; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Ruan Q; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Shi S; 2020 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Wang Da; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Wang Db; 2020 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Wang La; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Wang Lb; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Wan S; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Wei J; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Xu X; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Yang F; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Yang X; 2020 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Yao W; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Zhang G; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Zhao X; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Zheng Y; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Zhou F; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

| Zou X; 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | No |

NA: Not applicable.

Items:

1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated?

2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined?

3. Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%?

4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants?

5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided?

6. For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured?

7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed?

8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)?

9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants?

10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time?

11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants?

12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants?

13. Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less?

14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)?

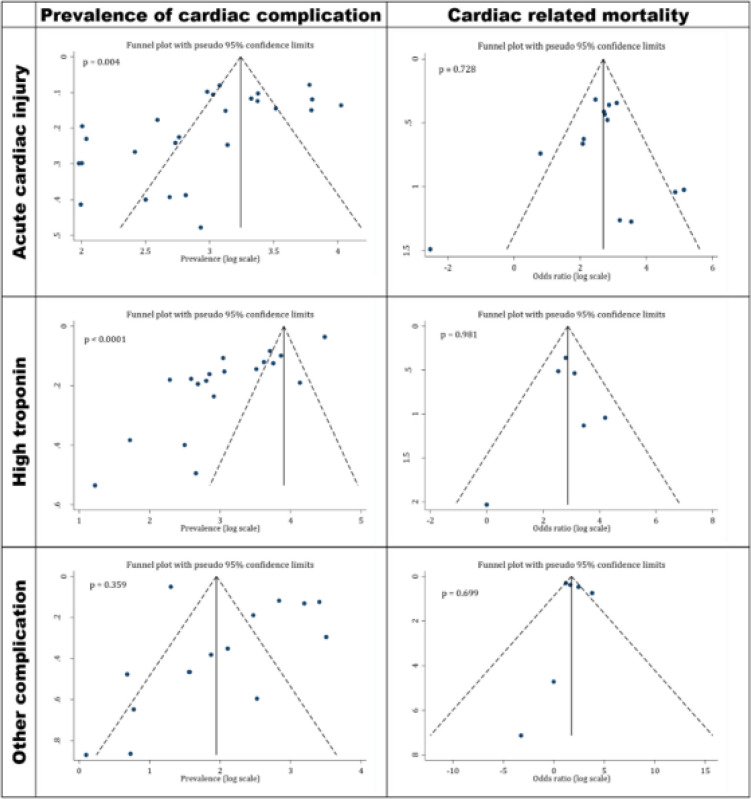

Publication bias

There were evidences of publication bias in the assessment of the prevalence of acute cardiac injury (Coefficient= -3.97; p=0.004) and abnormal serum troponin level (Coefficient = -8.65; p < 0.001) among the included studies. However, no evidence of publication bias was observed in the assessment of cardiac related mortality and the prevalence of other cardiac complications (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for publication bias in prevalence of cardiac complications in COVID-19 patients and mortality rate after incidence of cardiac manifestation. There are evidences of publication bias among the studies, which reported prevalence of cardiac complications. While, no publication bias was observed regarding the relationship of cardiac complication and mortality in COVID-19 patients

Meta-analysis

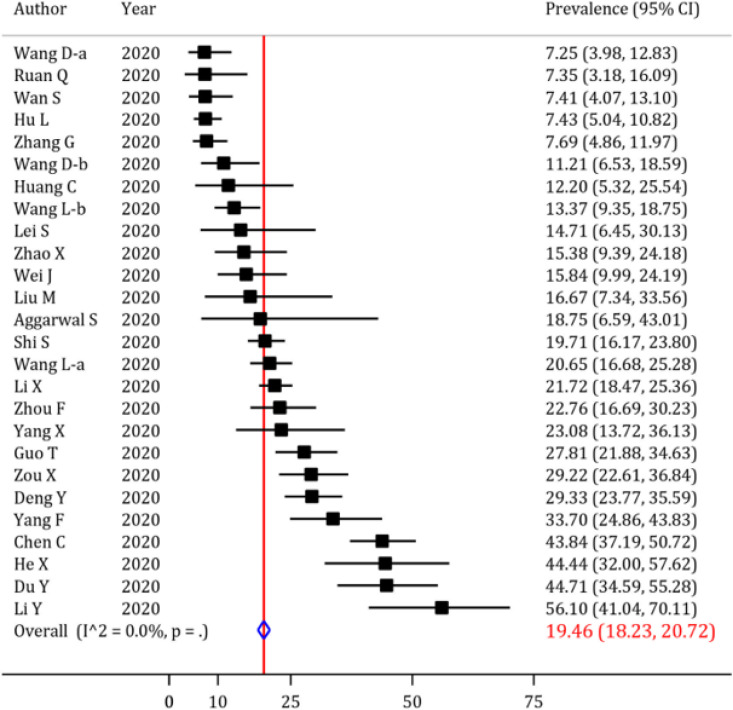

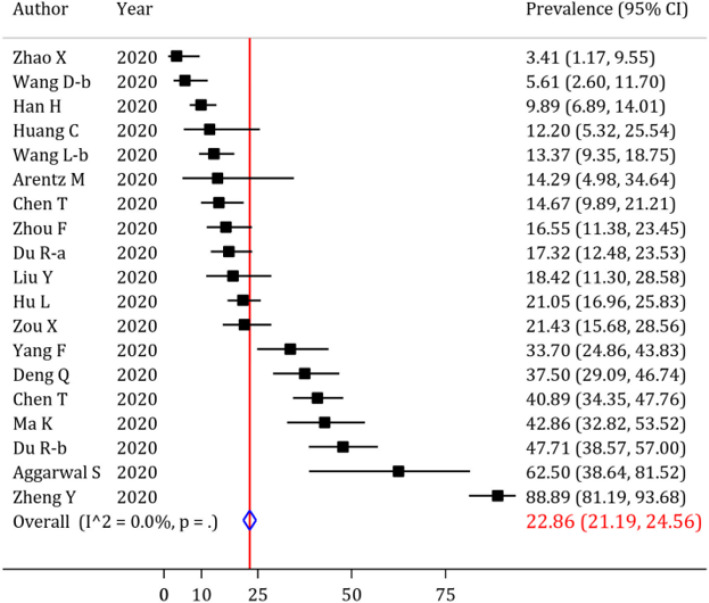

In the beginning, the prevalence of cardiac complications following SARS-CoV-2 infection was evaluated, and the results are depicted in figures 3, 4, 5 and 6, and table 3. Abnormal serum level of troponin was observed in 22.86% (95% CI: 21.19 to 24.56) of the patients (Figure 4). Moreover, the prevalence of acute cardiac injury, heart failure and cardiac arrest was 19.46% (95% CI: 18.23 to 20.72), 19.07% (95% CI: 15.38 to 23.04) and 3.44% (95% CI: 3.08 to 3.82), respectively (Figure 3 and Table 3). Furthermore, the I2 test revealed no heterogeneity regarding the prevalence of abnormal troponin levels and acute cardiac injury. The prevalence of other cardiac complications including myocarditis, cardiac insufficiency, pericardial effusion, myocardial infarction, and cardiomyopathy are depicted in Table 3. Sensitivity analysis showed that after excluding the studies with a high prevalence rate, the prevalence of abnormal serum level of troponin (20.16%; 95% CI: 18.54 to 21.82; cut off for high prevalence rate=50%) and acute cardiac injury (17.17%; 95% CI: 15.94 to 18.43; cut off for high prevalence rate=30) decreased slightly.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the assessment of the prevalence of acute cardiac injury in COVID-19 patients; CI: confidence interval

Figure 4.

Forest plot for the assessment of the prevalence of abnormal troponin levels in COVID-19 patients; CI: confidence interval

Figure 5.

Forrest plot for the assessment of risk of mortality in COVID-19 patients with acute cardiac injury; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

Figure 6.

Forrest plot for the assessment of risk of mortality in COVID-19 patients with abnormal troponin level; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

Table 3.

Summary of findings regarding cardiac complications in COVID-19

| Complication | Number of studies | Prevalence | 95% CI | Number of studies | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute cardiac injury | 26 | 19.46 | 18.23, 20.72 | 14 | 14.24 | 8.67, 23.38 | <0.001 | |

| Abnormal troponin | 19 | 22.86 | 21.19, 24.56 | 6 | 19.03 | 11.85, 30.56 | <0.001 | |

| Heart failure | 4 | 19.07 | 15.38, 23.04 | 2 | 10.66 | 5.69, 19.97 | <0.001 | |

| Cardiac arrest | 3 | 3.44 | 3.08, 3.82 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.00, >999.0 | 0.651 | |

| Myocarditis | 2 | 3.66 | 0.88, 7.82 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00, >999.0 | >0.99 | |

| Pericardial effusion | 2 | 2.62 | 0.58, 5.73 | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Cardiac insufficiency | 2 | 15.06 | 12.15, 18.22 | 2 | 4.65 | 2.82, 7.66 | <0.001 | |

| Cardiomyopathy | 1 | 33.33 | 17.19, 54.63 | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 | 6.52 | 3.02, 13.51 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

---: No data; CI: Confidence interval

Further analysis revealed that the odds of mortality in COVID-19 patients with acute cardiac injury is 14.24 (OR = 14.24, 95% CI: 8.67 to 23.38) times higher than the COVID-19 patients without acute cardiac injury. However, I2 test showed some degrees of heterogeneity regarding the relationship of cardiac complication and mortality of COVID-19 patients (Figure 5). There is a possible outlier study in acute cardiac injury section. After excluding this study, the odds of mortality in COVID-19 patients with acute cardiac injury is increased slightly (OR=15.77; 95% CI: 10.49 to 23.69). In the sensitivity analysis the heterogeneity was decreased (I2=45.5%).

Moreover, the odds of mortality in a COVID-19 patient presenting with abnormal serum troponin level in his/her blood sample was 19.03 (OR=19.03; 95% CI: 11.85 to 30.56) times higher than the patients not having this manifestation. Interestingly, no heterogeneity was observed when calculating the OR for the mortality in COVID-19 patients with abnormal serum troponin level (Figure 6). There are two possible outlier studies in abnormal troponin level section. After excluding these studies, the odds of mortality in COVID-19 patients with acute cardiac injury is increased slightly (OR=17.07; 95% CI: 10.41 to 27.99). The odds of mortality of patients having other cardiac complications are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we investigated the prevalence of 9 cardiac complications in COVID-19 patients and their subsequent mortality rates. Abnormal serum level of troponin with 22.86% prevalence, detected by laboratory tests, and acute cardiac injury with 19.46% prevalence, diagnosed with laboratory test results and other diagnostic techniques, were among the most prevalent complications/abnormalities observed in COVID-19 patients. Although a large number of studies reported the prevalence of the two mentioned cardiac complications, no heterogeneity was observed in this section. To contemplate even more on the matter, the prevalence of abnormal troponin level and acute cardiac injury are rather close numbers, which might mean that by close observation of troponin changes in a COVID-19 patient, we could possibly anticipate acute cardiac injuries in them and take appropriate measures. However, serum troponin levels also increase due to damage to other tissues, such as the kidneys, which may make it impossible to use troponin level alone to detect cardiac damage. Other cardiac complications such as heart failure and cardiomyopathy were also prevalent among the patients. However, with the small number of the studies observing them, more data is needed on the matter.

Regarding the limitations, each individual article used a different reference range for troponin or other injury indicators to be classified as abnormal, and each one used different diagnostic and laboratory test results to define acute cardiac injury, which could cause slight differences in the reported prevalence of acute cardiac injury and abnormal serum level of troponin. For example, Huang et al. defined acute cardiac injury as cardiac troponin rising to 3 or more times than normal or appearance of new abnormalities in echocardiography or ECG (19); While many others defined it only with the appearance of abnormal troponin levels in blood samples. Moreover, some articles’ study population only consisted of critically ill patients or deceased ones, which could shift prevalence statistics, causing inevitable heterogeneity in reported numbers (5, 15, 32). Additionally, it is worth mentioning that the mechanism of myocardial injury, whether being done by direct viral invasion to the host tissue or due to imbalanced homeostasis, was of no concern for the writers at the time. Although more research should be conducted to identify the exact causes of this damage, the effects it carries are the most important subject that should be studied at these critical times. Even though limitations were present in data reporting the prevalence of cardiac outcomes, it is important to pay enough attention to these complications, since many of them are directly related to patients’ general situation and illness severity.

On the other hand, our study shows intriguing data regarding mortality rate in patients presenting with cardiac complications, especially acute cardiac injury and abnormal serum level of troponin. Abnormal troponin levels are associated with about 19 times higher mortality risk in COVID-19 patients, which is of great importance in disease management for health care providers around the world. Considering the fact that no heterogeneity was observed regarding the risk of mortality in patients with abnormal troponin level, laboratory screening during routine patient assessments can be critical in early detection of cardiac injury and intervening accordingly. In addition, we suggest that blood levels of troponin should be evaluated as a prognostic factor in patients with cardiac involvement.

Furthermore, our data indicated that acute cardiac injury could raise the mortality to about 14 times more in COVID-19 patients. However, this number was associated with an overall heterogeneity, which could be attributed to different definitions of cardiac injury in studies, discussed above. Nonetheless, although one can conclude that there is a relationship between acute cardiac injury following COVID-19 and increased risk of mortality, the threat that acute cardiac injury poses to patients’ health status in the future is undeniable and demands careful monitoring and managements when confronting this situation. Moreover, it is noteworthy that articles reporting mortality rates of cardiac complications were mostly focused on abnormal troponin level and myocardial injury and the number of the articles reporting correlations between other cardiac complications such as heart failure, and mortality rate was very few; so, we cannot present an exact estimation of the contribution of other cardiac outcomes such as heart failure and myocarditis to patients’ fatality. In addition, inability to blind the outcome assessors in the studies and some articles not explicitly presenting inclusion and exclusion criteria were further limitations detected in the studies.

Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis and excluded possible outlier studies. The overall effect size slightly changed and therefore, the results seem to be robust.

To conclude, our findings thoroughly approve of other published articles investigating associations between COVID-19 cardiac outcomes and related mortalities (47, 48), confirming that cardiac injury, regardless of the mechanism of establishment, is a factor determining disease severity and patient prognosis reliably in large scale and should be considered and monitored from early stages of disease.

Conclusion

Cardiac complications/abnormalities can be prevalent in COVID-19 patients in the forms of acute cardiac injury, serum troponin levels abnormalities, heart failure, cardiac arrest, and other types. The importance of cardiac involvements is further highlighted when observing the higher mortality rate among COVID-19 patients presenting with cardiac involvements. Thus, careful monitoring of heart involvements should be performed in COVID-19 patients.

Abbreviations

SARS-CoV-2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019

ACE2: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2

PECO: Problem, Exposure, Comparison, Outcome

NHLBI: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

CI: Confidence Interval

OR: Odds Ratio

ECG: Electrocardiography

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received ethics approval from Ethics committee of Iran University of medical Sciences.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors’ contribution

Study design: MY, MHA; Data gathering: AT, DM, AMN, MY; Analysis: MY; Interpreting the results: MY, MHA; Drafting: AT, DM, AMN; Critically revised the paper: All authors.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Coronavirus disease 2019 ( COVID-19): situation report, 121. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New England journal of medicine. 2020;382(18):1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. Jama. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du Y, Tu L, Zhu P, Mu M, Wang R, Yang P, et al. Clinical Features of 85 Fatal Cases of COVID-19 from Wuha A Retrospective Observational Study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2020;201(11):1372–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu H, Ma F, Wei X, Fang Y. Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis treated with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. European heart journal. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health NIo. Study Quality Assessment Tools| National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) National Institutes of Health. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrasa H, Rello J, Tejada S, Martín A, Balziskueta G, Vinuesa C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in Spanish intensive care: early experience with 15-day survival in Vitoria. Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C, Yan J, Zhou N, Zhao J, Wang D. Analysis of myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 and association between concomitant cardiovascular diseases and severity of COVID-19. Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi. 2020:48:E008–E. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200225-00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. Bmj. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng Q, Hu B, Zhang Y, Wang H, Zhou X, Hu W, et al. Suspected myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19: Evidence from front-line clinical observation in Wuhan, China. International journal of cardiology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.03.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng Y, Liu W, Liu K, Fang Y-Y, Shang J, Zhou L, et al. Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study. Chinese medical journal. 2020;133(11):1261–7. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du R-H, Liang L-R, Yang C-Q, Wang W, Cao T-Z, Li M, et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. European Respiratory Journal. 2020;55:5. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du R-H, Liu L-M, Yin W, Wang W, Guan L-L, Yuan M-L, et al. Hospitalization and critical care of 109 decedents with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2020 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-225OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA cardiology. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han H, Xie L, Liu R, Yang J, Liu F, Wu K, et al. Analysis of heart injury laboratory parameters in 273 COVID‐19 patients in one hospital in Wuhan, China. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He X, Lai J, Cheng J, Wang M, Liu Y, Xiao Z, et al. Impact of complicated myocardial injury on the clinical outcome of severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients. Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi. 2020:48:E011–E. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200228-00137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei S, Jiang F, Su W, Chen C, Chen J, Mei W, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020:100331. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li K, Wu J, Wu F, Guo D, Chen L, Fang Z, et al. The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Investigative radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao Y, Zhou Y, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Hu Y, Yu J, Ma T. Retrospective analysis of laboratory testing in 54 patients with severe-or critical-type 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Laboratory Investigation. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41374-020-0431-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu M, He P, Liu H, Wang X, Li F, Chen S, et al. Clinical characteristics of 30 medical workers infected with new coronavirus pneumonia. Zhonghua jie he he hu xi za zhi= Zhonghua jiehe he huxi zazhi= Chinese journal of tuberculosis and respiratory diseases. 2020:43:E016–E. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Liao W, Wan L, Xiang T, Zhang W. Correlation between relative nasopharyngeal virus RNA load and lymphocyte count disease severity in patients with COVID-19. Viral immunology. 2020 doi: 10.1089/vim.2020.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA cardiology. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan S, Xiang Y, Fang W, Zheng Y, Li B, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID‐19 patients in northeast Chongqing. Journal of medical virology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(11):1061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, He W, Yu X, Hu D, Bao M, Liu H, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. Journal of Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L, He W, Yu X, Liu H, Zhou W, Jiang H. Prognostic value of myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19. [Zhonghua yan ke za Zhi] Chinese Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020:56:E009–E. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200313-00202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu X, Yu C, Qu J, Zhang L, Jiang S, Huang D, et al. Imaging and clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04735-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang F, Shi S, Zhu J, Shi J, Dai K, Chen X. Analysis of 92 deceased patients with COVID‐19. Journal of medical virology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Liu H, Wu Y, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao W, Wang T, Jiang B, Gao F, Wang L, Zheng H, et al. Emergency tracheal intubation in 202 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: lessons learnt and international expert recommendations. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang G, Hu C, Luo L, Fang F, Chen Y, Li J, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 221 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2020:104364. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng Y, Xu H, Yang M, Zeng Y, Chen H, Liu R, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and clinical features of 32 critical and 67 noncritical cases of COVID-19 in Chengdu. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2020:104366. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zou X, Li S, Fang M, Hu M, Bian Y, Ling J, et al. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II Score as a Predictor of Hospital Mortality in Patients of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Critical care medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu L, Chen S, Fu Y, Gao Z, Long H, Wang J-m, et al. Risk factors associated with clinical outcomes in 323 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in Wuhan, China. Clinical infectious diseases. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei J-F, Huang F-Y, Xiong T-Y, Liu Q, Chen H, Wang H, et al. Acute myocardial injury is common in patients with covid-19 and impairs their prognosis. Heart. 2020 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D, Yin Y, Hu C, Liu X, Zhang X, Zhou S, et al. Clinical course and outcome of 107 patients infected with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, discharged from two hospitals in Wuhan, China. Critical Care. 2020:24:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02895-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aggarwal S, Garcia-Telles N, Aggarwal G, Lavie C, Lippi G, Henry BM. Clinical features, laboratory characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Early report from the United States. Diagnosis. 2020;7(2):91–6. doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baldi E, Sechi GM, Mare C, Canevari F, Brancaglione A, Primi R, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the Covid-19 outbreak in Italy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao X-Y, Xu X-X, Yin H-S, Hu Q-M, Xiong T, Tang Y-Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in a non-Wuhan area of Hubei Province, China: a retrospective study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2020:20:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05010-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma K-L, Liu Z-H, Cao C-f, Liu M-K, Liao J, Zou J-B, et al. COVID-19 myocarditis and severity factors: an adult cohort study. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. Jama. 2020;323(16):1612–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive care medicine. 2020;46(5):846–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu H, Rhee J-W, Cheng P, Waliany S, Chang A, Witteles RM, et al. Cardiovascular complications in patients with COVID-19: consequences of viral toxicities and host immune response. Current cardiology reports. 2020;22:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01292-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santoso A, Pranata R, Wibowo A, Al-Farabi MJ, Huang I, Antariksa B. Cardiac injury is associated with mortality and critically ill pneumonia in COVID-19: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].