Abstract

Changes in dietary habits and association with lifestyle during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown in the Kosovo population have not been studied yet. Therefore, the intent of the present study was to determine whether if COVID-19 lockdown had any impact in lifestyle, including dietary habits and physical activity (PA) patterns of people from different areas of Kosovo. Dietary habits, PA, body weight and sociodemographic variables were measured through validated online survey started one week after lockdown decision and lasted for next two month (May and June 2020). Six hundred eighty-nine participants (women 79% and men 21%) aged between 20 and 65 years from the Kosovo territory participated in the research. Multivariate models showed that participants in family home residence, participants from Gjilan, participants female and participants with professional educations reported a higher likelihood of turning into a higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) (OR: 6.09, 5.25, 5.17, 4.19, respectively). The weight gained during the lockdown was positively associated with a higher cooking frequency (OR; 2.90, p < 0.01), lower meat and fish consumption (OR; 1.15, p = 0.02; OR; 1.04, p = 0.04, respectively), higher fast-food consumption (OR; 0.49, p = 0.02) and no physical activity performance (OR; 0.43, p = 0.02) during the COVID-19 lockdown. The dietary habits during COVID-19 lockdown could be related to the improvements in adherence to the MedDiet and physical activities that may minimize related health complications.

Keywords: COVID-19, Body weight, Lockdown, Mediterranean diet, Nutritional survey, Physical activity

1. Introduction

Investigations show that the lockdown during COVID-19 has had an inverse effect on psychological conditions such as psychological disturbance (Brooks et al., 2020). It has been associated with negative attitude changes involving a rise in smoking (45%), increased and decreased consumption of alcohol, weight gain or, uncontrolled eating of unhealthy food and snacks (Ammar et al., 2020; Anne et al., 2020; Carroll et al., 2020; Sidor & Rzymski, 2020). On March 13, 2020, the first cases of COVID-19 were recorded in Kosovo and according to the analysis of NIPHK (National Institute of Public Health of Kosovo) two people have tested positive for COVID-19, with stable health (Kosovo Government, 2020). From March to December, there were various measures and decisions which were taken by the Government of the Republic of Kosovo. The measures were strict, starting with closing and moving at certain times making people spend a longer time with their families, preparing food and meals at home. Since some of the main food products consumed in this period were pastries and other sweets, this affected the increase in body weight. But over time the measures began to soften, the citizens began to move freely and continued with their work, until the second wave of the pandemic with more cases affected psychological, emotional and health condition (Kosovo Government, 2020). Changes in dietary habits were noticed during the lockdown reported by some research, evidenced a correlation between a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) and higher intake of junk food, snacks, and sugar drink during the lockdown (Ashby, 2020; Di Renzo et al., 2020; Pietrobelli et al., 2020). On the contrary, other research showed an adherence to a healthier diet during the first weeks of lockdown (Giacalone et al., 2020; Kriaucioniene et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020). The relationship between diet and health is well-stablished, thus, nutritional behavior threatens the health and therefore managing an excellent diet is essential for boosting the immune system (Kriaucioniene et al., 2020). Indeed, serious obesity is one of the groups with the highest risk for COVID-19 difficulties because the adipose tissue contributes to the inflammatory medium and oxidative stress level (Di Renzo et al., 2019; USA Government, 2020).

The MedDiet is made of a perfect mix of good foods, containing all macro and micronutrients, which is the key factor against inflammatory responses, due to their low cholesterol levels and high levels of antioxidants and monounsaturated fatty acid (De Lorenzo et al., 2017). Moreover, Rodríguez-Pérez et al. (2020) reported that a higher MedDiet adherence could have a positive impact on the prevention of COVID-19-related complications. Therefore, taking this into consideration, the purpose of this research was to investigate self-reported nutritional behavior and weight gain/physical activity performance during the COVID-19 lockdown among a representative adult population from Kosovo and to evaluate socio-demographic variance in nutrition and eating behaviors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study sample and data collection

The online cross-sectional survey was carried out between individuals older than 18 years in Kosovo as part of the international COVIDiet (COVIDiet_Int) project with ID number: NCT04449731 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04449731) managed by the University of Granada, Spain (Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020). The survey began on 5 May; a week after COVID-19 lockdown started in Kosovo and lasted eight weeks. A self-administered anonymous web-based questionnaire was developed to collect data. The respondents were grouped into five age groups: under 20 years, 20–35 years, 35–50 years, 51–65, and older (over 65). Education level respondents were categorized into six groups: primary, secondary, high, bachelor, master, and Ph.D. level of education. The full questionnaire is available online at https:// www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/6/1730/s1 (the Albanian translation can be obtained from the authors upon request). Briefly, three main sections of the items were divided as follow (1) Socio-demographic information questions (sex, age, place of residence, country, dependent children, level of studies), (2) PREDIMED MedDiet Adherence Screener (14 questions of MEDAS) (Martínez-González et al., 2012) and actual changes and lastly (3) 21 questions with the purpose to research variation during regular eating habits throughout the lockdown, i.e., frequency and way of cooking, type of oil for frying, alcohol intake, snacking, between others. All items were also arranged to realize if contributors decreased, increased, or maintained their routine during the COVID-19 lockdown. Also, physical activity and body weight changes were assessed through two questions. The link to the survey was disseminated using social networking sites, web-pages of some institutions, which agreed to participate and social media such as Facebook, with the intention of reaching the highest number of participants from all administrative districts of Kosovo.

2.2. Ethical issues

The international COVIDiet study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Granada (1526/CEIH/2020). Additionally, the Kosovo COVIDiet study was approved by the Bioethics Centre of the University of Tetova. Participation was voluntary, anonymous and no personal data were collected. The participants were informed about the objectives of the study.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics for all the collected variables were derived by levels of adherence to the MedDiet and by sex, age, level of education, and region. Student's t-test or Kruskal-Wallis test (for continuous normal or non-normal distributed data, respectively), and Chi-squared tests (for categorical data) were used to evaluate differences in means or proportions by these variables across the strata. Box-plots were also used to evaluate further the distribution of the variable on adherence to the MedDiet by the aforementioned subgroups. Adherence to the MedDiet was assessed on the continuous scale (range: 0–14) and on the categorical scale by classifying participants into low, medium, and high adherence levels (<5, 6 to 8 and > 9 points, respectively) to the MedDiet at the two-time points: before and during the COVID-19 Kosovo lockdown. A binary variable to assess the change in adherence to the MedDiet was built to distinguish between those who kept adherence to the MedDiet alike (reference category, set to zero) and those who changed their adherence towards a greater adherence (set to one). Logistic regression models were used to explore variables associated with the change in adherence (change versus non-change, as reference) to the MedDiet. Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were estimated in univariate regression models. The threshold for statistical significance in two-sided tests was set at p-value = 0.05. Data were analyzed with SPSS (version16.0).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Sociodemographic and regional characteristics of the study sample

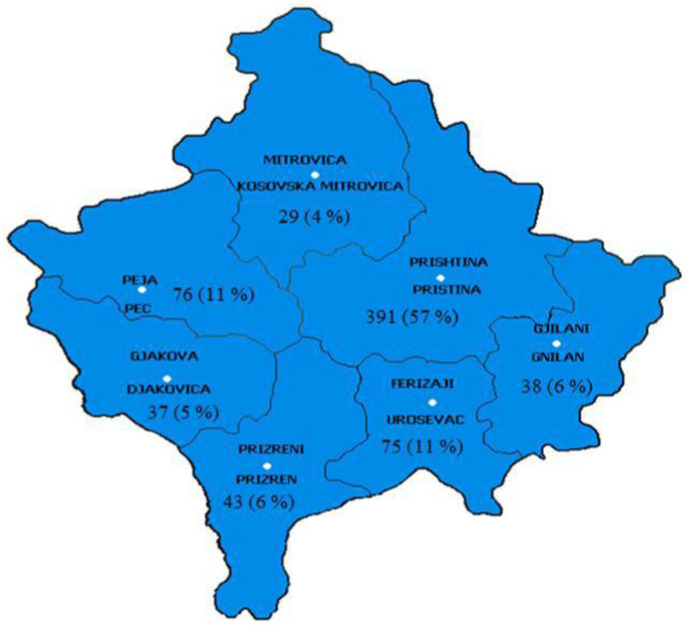

In total, 689 individuals from Kosovo (488 females and 200 males) participated in the survey and completed the questionnaire (Table 1 ). Most participants were 20–35 years old (59%) and the highest percentage of the sample had university studies (54%), were living in the family home (56.7%), and with no children in care (62%) (Table 2 ). About 71% of the participants were females, 57% were from the district of Pristina (Fig. 1 ), and only few participants became from the oldest (0.4%) and middle oldest age groups (8.8%). No statistical difference was found for participants that were more likely to live in family homes, and no significant differences by regions between gender levels were noted (except for Mitrovica). However, a statistically significant interaction by gender was observed between change in adherence to the MedDiet and children in care (p-value = 0.000 and 0.004, respectively). According to Table 5, positive answers to the MEDAS questionnaire and the adherence to MD are reported in terms of territorial coverage over the Kosovo administrative districts. Results from the MEDAS questionnaire in our population sample, classified according to the regional participation, demonstrated significantly variations (p = 0.018) and that most of subjects had more than 50% of olive oil (61% in Gjilan, 57% in Pristina, 55% in Mitrovica, and 51% in Gjakova). Olive oil consumption has been traditionally highlighted to contribute to the prosperity well-being of the Mediterranean people, and nowadays there is consistent evidence supporting its association with lower all-cause mortality and reduced risk of cardio vascular disease (Campanini et al., 2017). The highest percentage of the study samples consumed 1–2 portions of vegetables per day (51%), 1–3 fruits per day (53%), and legumes 1 time per week (47%) with no significant difference between the regions were found. Regarding vegetable consumption, results from the MEDAS questionnaire showed that more than 50% increased their intake only the region of Pristina (54%) while the increase of fruits consumption was higher in the regions from Prizren (63%), Ferizaj (61%) and Gjilan (58%). Our finding pertaining higher fruit and vegetable consumption during Kosovo COVID-19 lockdown were inconsistent with the previous findings which reported the opposite trend (Amar et al., 2020; Deschasaux-Tanguy et al., 2020; Di Renzo et al., 2020; Pellegrini et al., 2020). Fruits and vegetables are rich in Zinc which is a necessary mineral in the maintenance and growth of adaptive and innate immune cells (Bonaventura et al., 2015). In agreement to the Italian study, positive changes related to the decrease of meat consumption, carbonated or sugary drinks and increased consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables were reported during the COVID-19 lockdown (Di Renzo et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020). The lower consumption of meat could be related with the lack of stock in some supermarkets, the same that happened in the Spanish supermarkets and grocery stores after the state of alarm was declared (Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020). Vieux et al. (2018) stated that meat consumption is proportional to the amount of greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions whereas others declared that consumption of red meat has been associated with chronic diseases like cancer (Springmann et al., 2018). The chi-square test showed differences in MEDAS score among the seven Kosova regions (p = 0.204), with higher scores in Gjilan and Prizren when compared to other administrative regions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (%).

| Characteristics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 200 | 29 | |

| Female | 488 | 71 | |

| Another | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Group ages | |||

| 18–35 | 492 | 71 | |

| 36–50 | 133 | 19 | |

| ≥51 | 64 | 10 | |

| Education | |||

| University | 605 | 88 | |

| Lower | 84 | 12 | |

| Body mass index | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 446 | 65 | |

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 195 | 28 | |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 48 | 7 | |

| Weight gain during quarantine | |||

| Gained | 258 | 38 | |

| No changes/didn't know | 431 | 62 | |

Table 2.

Standards characteristics of respondents by level of adherence to the MedDiet during the COVID-19 Kosovo confinement.

| Low (N = 339) |

Medium (N = 325) |

High (N = 25) |

p Valuec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Gendera | 0.000 | |||||||

| Men | 132 | 39 | 63 | 19 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Woman | 206 | 61 | 262 | 81 | 20 | 80 | ||

| Another | 1 | |||||||

| Place of Residence | 0.089 | |||||||

| Family home | 325 | 96 | 312 | 96 | 24 | 96 | ||

| Alone | 5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Student residence | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Shared flat | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Region by Areasb | 0.204 | |||||||

| Prishtina | 184 | 54 | 193 | 59 | 14 | 56 | ||

| Peja | 37 | 11 | 36 | 11 | 3 | 12 | ||

| Ferizaj | 40 | 12 | 33 | 10 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Prizren | 24 | 7 | 17 | 5 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Gjilan | 16 | 5 | 19 | 6 | 3 | 12 | ||

| Gjakova | 24 | 7 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mitrovica | 14 | 4 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Children in Care | 0.004 | |||||||

| Yes | 110 | 32 | 139 | 43 | 14 | 56 | ||

| No | 229 | 68 | 186 | 57 | 11 | 44 | ||

| Education Level | 0.310 | |||||||

| Faculty | 192 | 57 | 166 | 51 | 13 | 52 | ||

| Master | 75 | 22 | 87 | 27 | 9 | 36 | ||

| Secondary | 42 | 12 | 33 | 10 | 2 | 8 | ||

| High | 12 | 4 | 23 | 7 | 1 | 4 | ||

| PhD | 13 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Elementary | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Age | 0.429 | |||||||

| <20 | 50 | 15 | 35 | 11 | 1 | 4 | ||

| 20–35 | 202 | 59 | 189 | 58 | 15 | 60 | ||

| 35–50 | 59 | 17 | 69 | 21 | 5 | 20 | ||

| 51–65 | 26 | 8 | 31 | 9 | 4 | 16 | ||

| >65 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

Numbers do not add up because there were five respondents who reported another gender (data not shown).

Kosovo Administrative regions.

Differences between the three MedDiet adherences groups were evaluated by the Chi-squared test.

Fig. 1.

Districts of Kosovo.

Table 5.

Comparisons between dietary behaviours relative to the MedDiet pattern by region during the COVID-19 Kosovo lockdown.

| Total |

Ferizaj |

Gjakova |

Gjilan |

Mitrovica |

Peja |

Pristina |

Prizren |

p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (689) | 75 (10.9) | 37 (5.4) | 38 (5.5) | 29 (4.2) | 776 (11) | 391 (56.8) | 43 (6.2) | |||

| Olive oil for cooking | 0.018 | |||||||||

| Yes | 361 (52) | 32 (43) | 19 (51) | 23 (61) | 16 (55) | 28 (37) | 223 (57) | 20 (47) | ||

| No | 328 (48) | 43 (57) | 18 (49) | 15 (39) | 13 (45) | 48 (63) | 168 (43) | 23 (53) | ||

| Olive oil (tablespoons/d) | 0.243 | |||||||||

| >4 | 169 (25) | 13 (17) | 6 (16) | 12 (32) | 8 (28) | 18 (24) | 106 (27) | 6 (13) | ||

| 2–3.9 | 242 (35) | 27 (36) | 12 (32) | 9 (24) | 10 (34) | 22 (28) | 145 (37) | 17 (40) | ||

| 0–1.9 | 278 (40) | 35 (47) | 19 (52) | 17 (44) | 11 (38) | 36 (47) | 140 (36) | 20 (47) | ||

| Vegetables (servings/d) | 0.289 | |||||||||

| >2 | 222 (32) | 30 (40) | 14 (38) | 8 (21) | 9 (31) | 27 (36) | 120 (31) | 14 (33) | ||

| 1–1.9 | 354 (51) | 35 (47) | 18 (49) | 17 (45) | 14 (48) | 37 (48) | 212 (54) | 21 (49) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 113 (17) | 10 (13) | 5 (14) | 13 (34) | 6 (21) | 12 (16) | 59 (15) | 8 (18) | ||

| Fruits (units/d) | 0.346 | |||||||||

| >3 | 211 (31) | 15 (20) | 13 (35) | 12 (32) | 11 (38) | 24 (32) | 127 (32) | 9 (21) | ||

| 1–2.9 | 356 (52) | 46 (61) | 19 (51) | 22 (58) | 16 (55) | 36 (47) | 190 (49) | 27 (63) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 122 (17) | 14 (19) | 5 (14) | 4 (10) | 2 (7) | 16 (21) | 74 (19) | 7 (16) | ||

| Red meat (servings/d) | 0.487 | |||||||||

| >1 | 248 (36) | 24 (32) | 19 (51) | 12 (34) | 11 (38) | 29 (38) | 140 (36) | 13 (30) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 441 (64) | 51 (68) | 18 (49) | 26 (68) | 18 (62) | 47 (62) | 251 (64) | 30 (70) | ||

| Fats (servings/d) | 0.201 | |||||||||

| >1 | 146 (21) | 14 (19) | 14 (38) | 5 (13) | 6 (21) | 16 (21) | 84 (21) | 7 (16) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 543 (79) | 61 (81) | 23 (62) | 33 (87) | 23 (79) | 60 (79) | 307 (79) | 36 (84) | ||

| Sweet beverages (servings/d) | 0.074 | |||||||||

| >1 | 244 (35) | 27 (36) | 13 (35) | 11 (29) | 14 (48) | 38 (50) | 127 (32) | 14 (33) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 445 (65) | 48 (64) | 24 (65) | 27 (71) | 15 (52) | 38 (50) | 264 (68) | 29 (67) | ||

| Wine (glasses/d) | 0.072 | |||||||||

| 0 | 509 (74) | 61 (81) | 31 (84) | 28 (74) | 26 (90) | 47 (62) | 283 (71) | 33 (77) | ||

| >7 | 9 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | 4 (1) | 1 (2) | ||

| 3–6.9 | 20(3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1(3) | 2 (7) | 1 (1) | 15 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

| 0–2.9 | 151 (22) | 13 (18) | 5 (13) | 9 (23) | 1 (3) | 25 (33) | 89 (23) | 9 (21) | ||

| Legumes (servings/w) | 0.701 | |||||||||

| >3 | 74 (10) | 10 (13) | 1 (3) | 6 (16) | 4 (14) | 9 (12) | 37 (8) | 7 (16) | ||

| 1–2.9 | 294 (43) | 33 (44) | 16 (43) | 19 (50) | 12 (41) | 32 (42) | 167 (43) | 15 (35) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 321 (47) | 32 (43) | 20 (54) | 13 (34) | 13 (45) | 35 (46) | 187 (48) | 21 (49) | ||

| Fish (servings/w) | 0.165 | |||||||||

| >3 | 36 (5) | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 1 (4) | 7 (9) | 16 (4) | 6 (14) | ||

| 1–2.9 | 252 (37) | 28 (37) | 13 (35) | 15 (39) | 16 (55) | 22 (29) | 144 (37) | 14 (33) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 401 (58) | 44 (59) | 23 (62) | 21 (56) | 12 (41) | 47 (62) | 231 (59) | 23 (53) | ||

| Non-homemade pastries (units/w) | 0.021 | |||||||||

| >2 | 291 (42) | 29 (39) | 18 (49) | 14 (37) | 11 (38) | 47 (62) | 155 (40) | 17 (40) | ||

| 0–1.9 | 398 (58) | 46 (61) | 19 (51) | 24 (63) | 18 (62) | 29 (38) | 236 (60) | 26 (60) | ||

| Nuts (servings/w) | 0.016 | |||||||||

| 3 | 133 (19) | 8 (11) | 4 (11) | 12 (32) | 4 (14) | 20 (26) | 79 (20) | 6 (14) | ||

| 1–2.9 | 245 (36) | 33 (44) | 12 (32) | 13 (34) | 17 (58) | 28 (37) | 130 (33) | 12 (28) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 311 (45) | 34 (45) | 21 (57) | 13 (34) | 8 (28) | 28 (37) | 182 (47) | 25 (58) | ||

| White meat preference | 0.973 | |||||||||

| yes | 540 (78) | 58 (77) | 27 (73) | 29 (76) | 23 (79) | 62 (82) | 307 (79) | 34 (79) | ||

| no | 149 (22) | 17 (23) | 10 (27) | 9 (24) | 6 (21) | 14 (18) | 84 (21) | 9 (21) | ||

| Sofrito3 (servings/w) | 0.109 | |||||||||

| >2 | 350 (51) | 34 (45) | 13 (35) | 19 (50) | 15 (52) | 49 (65) | 202 (52) | 18 (41) | ||

| 1–1.9 | 217 (31) | 30 (40) | 19 (51) | 11 (29) | 8 (28) | 16 (21) | 119 (30) | 14 (33) | ||

| 0–0.9 | 122 (18) | 11 (15) | 5 (14) | 8 (21) | 6 (20) | 11 (14) | 70 (18) | 11 (26) | ||

| Adherence to the MD | ||||||||||

| Low | 339 (49) | 40 (53) | 24 (65) | 16 (42) | 14 (48) | 37 (49) | 184 (47) | 24 (56) | ||

| Medium | 289 (42) | 33 (44) | 13 (35) | 19 (50) | 14 (48) | 36 (47) | 193 (49) | 16 (37) | ||

| High | 61(9) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 3 (4) | 14 (4) | 3 (7) | ||

Positive answers to MEDAS questionnaire. Compliance rates of at least 50% are indicated in bold. Data are expressed as number and percentage in parenthesis (n %). Differences between the regions groups were evaluated by the Chi-squared test (p < 0.05).

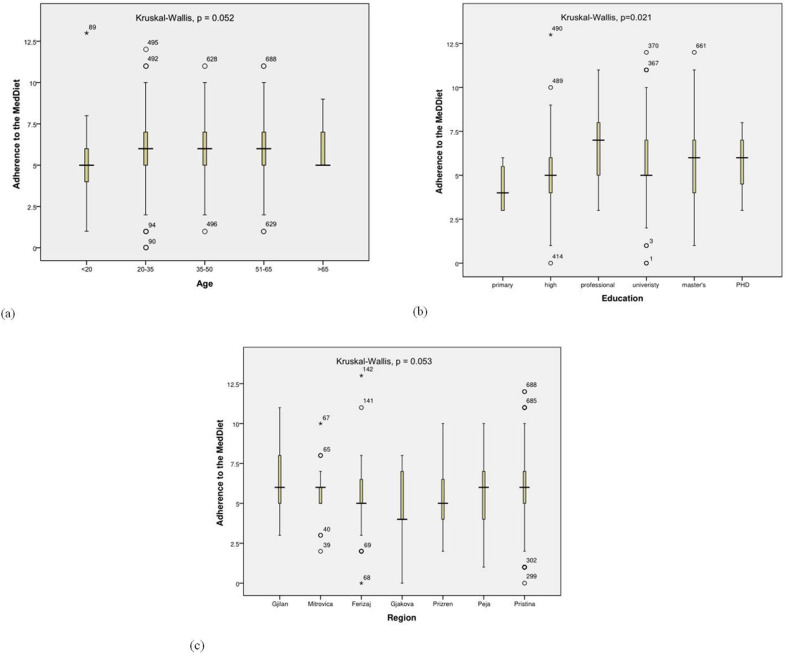

3.2. Dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 confinement

Socio-demographic factors associated with the change in the adherence to the MedDiet are presented in Table 6. Multivariate models found that female participants (OR: 5.17), participants lived in the family home (OR: 6.09), participants with high education level and participants with ages from 51 to higher than 65 years old (OR < 0.70) presented a higher odd of change to adhere to the MedDiet during the lockdown. On the contrary PhD respondents (OR: 0.04) and those who lived alone (OR: 0.99) from Gjakova had lower adherence to the MedDiet (Table 6). Kruskal Walli's analysis showed that no significant association was observed between the change in MedDiet adherence and the age and region but the level of education showed significant association to the change in MedDiet adherence (Fig. 2 ). So the age and geographical region were not found to modify the associations with adherence. Dietary and lifestyle adaptations by gender during the COVID-19 Kosovo lockdown are shown in Table 3 . Overall, most participants did not increase their intake of alcohol level (52% maintained it and 43% decreased it), as well as their physical activity level (41%) which remained lower during the lockdown. Furthermore, the majority cooked in a higher frequency than before the lockdown and used boiling as the main technique for cooking (53%). The intake of snacks and fried foods was reported similar as before COVID-19 lockdown for 45% and 52% of participants, respectively while 51% of participants showed significant (p < 0.05) lower frequency of fast-food intake. However, around 57% of the participants continued consuming fried foods 1–3 days a week and around 32%, more than 7 times per week. Similarly to the Spanish COVIDiet Study (Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2020), 62% of participant reported not to eat more during the lockdown. The greater part of the participants (52%) used sunflower oil for frying. In contrast to our results, a study conducted in Spanish adults reported that the subjects increased consumption of olive oil during lockdown (Reyes-Olavarría et al., 2020). Concerning anthropometric principle, 37% of the participants reported weight gain and 47% reported the opposite with a higher prevalence in female participants (68.9%). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, overweight was defined as BMI 25–29 kg/m2 and obesity as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (WHO, 2000). The participants reported a lower PA (times/week and min/session, p > 0.05) than before lockdown.

Table 6.

Factors associated with adherence to the MedDiet during Kosovo lockdown.

| High vs medium - low adherence to MedDiert |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Model |

|||

| OR | 95% CI | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | Ref | Ref | |

| Female | 5.17 | [2.04–13.10] | |

| Another | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Place of Residence | |||

| Shared flat | Ref | Ref | |

| Family home | 6.09 | 0.00 | |

| Student residence | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| Alone | 0.99 | 0.00 | |

| Region by Areas | |||

| Mitrovica | Ref | Ref | |

| Gjilan | 5.25 | 0.59–46.30 | |

| Pristina | 3.19 | 0.42–24.08 | |

| Ferizaj | 0.77 | 0.67–8.80 | |

| Gjakova | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | |

| Prizren | 2.10 | 0.21–21.24 | |

| Peja | 3.76 | 0.45–31.10 | |

| Children in Care* | |||

| No | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.52 | [0.31–0.89] | |

| Education Level | |||

| Elementary | Ref | Ref | |

| Secondary | 1.81 | [0.20–16.19] | |

| High | 4.19 | [0.46–38.20] | |

| University | 2.29 | [0.30–17.45] | |

| Master | 3.66 | [0.47–28.43] | |

| PhD | 0.04 | ||

| Age | |||

| >65 | Ref | Ref | |

| <20 | 0.17 | [0.02–1.56] | |

| 20–35 | 0.58 | [0.19–1.80] | |

| 35–50 | 0.45 | [0.11–1.84] | |

| 51–65 | 0.70 | 0.00 | |

Fig. 2.

Adherence to the MedDiet during the Kosovo COVID-19 lockdown by subgroups of age (a), educational level (b) and region (c).

Table 3.

Dietary and lifestyle adjustment by level of adherence to the MedDiet during the COVID-19 Kosovo confinement.

| All |

Low |

Medium |

High |

p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 689) |

(N = 339) |

(N = 325) |

(N = 25) |

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Meals out of home | 0.174 | |||||||||

| 0 | 112 | 16 | 51 | 15 | 58 | 18 | 3 | 12 | ||

| 1 | 193 | 28 | 90 | 26 | 97 | 30 | 6 | 24 | ||

| 2 | 273 | 40 | 131 | 39 | 128 | 39 | 14 | 56 | ||

| 3 | 111 | 16 | 67 | 20 | 42 | 13 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Alcohol intake | 0.003 | |||||||||

| As before | 362 | 52 | 174 | 51 | 176 | 54 | 12 | 48 | ||

| Lower | 299 | 43 | 156 | 46 | 136 | 42 | 7 | 28 | ||

| Higher | 28 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 13 | 4 | 6 | 24 | ||

| Type of Cooking | 0.104 | |||||||||

| Microwave | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Bake | 205 | 30 | 116 | 34 | 79 | 24 | 10 | 40 | ||

| Fried | 54 | 8 | 31 | 9 | 21 | 7 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Frying | 58 | 8 | 24 | 7 | 32 | 10 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Boiling | 366 | 53 | 166 | 49 | 189 | 58 | 11 | 44 | ||

| Frequency of Cooking | 0.150 | |||||||||

| As before | 255 | 37 | 131 | 39 | 119 | 36 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Lower | 49 | 7 | 26 | 8 | 22 | 7 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Higher | 385 | 56 | 182 | 53 | 184 | 57 | 19 | 76 | ||

| Fried Foods Intake | 0.678 | |||||||||

| As before | 355 | 52 | 184 | 54 | 156 | 48 | 15 | 60 | ||

| Lower | 174 | 25 | 79 | 23 | 90 | 28 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Higher | 160 | 23 | 76 | 23 | 79 | 24 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Fried Foods Frequency Per Week | 0.718 | |||||||||

| <1 | 178 | 26 | 80 | 24 | 91 | 28 | 7 | 28 | ||

| 1–3 | 392 | 57 | 201 | 58 | 178 | 55 | 13 | 52 | ||

| 4–6 | 77 | 11 | 36 | 10 | 37 | 11 | 4 | 16 | ||

| Never | 34 | 5 | 19 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| >7 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Oil used for frying | 0.744 | |||||||||

| Another | 15 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Canola Oil | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Sunflower Oil | 355 | 52 | 175 | 52 | 168 | 52 | 12 | 48 | ||

| Corn Oil | 85 | 12 | 35 | 10 | 45 | 14 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Olive Oil | 231 | 34 | 122 | 36 | 102 | 31 | 7 | 28 | ||

| Snacking frequency | 0.940 | |||||||||

| As before | 311 | 45 | 151 | 44 | 152 | 47 | 8 | 32 | ||

| Lower | 139 | 20 | 68 | 21 | 65 | 19 | 6 | 24 | ||

| Higher | 239 | 35 | 120 | 35 | 108 | 34 | 11 | 44 | ||

| Fast food frequency | 0.022 | |||||||||

| As before | 243 | 35 | 105 | 31 | 127 | 40 | 11 | 44 | ||

| Lower | 352 | 51 | 190 | 56 | 151 | 46 | 11 | 44 | ||

| Higher | 94 | 14 | 44 | 13 | 47 | 14 | 3 | 12 | ||

| Eating more | 0.616 | |||||||||

| upper/yes | 262 | 38 | 131 | 39 | 123 | 38 | 8 | 32 | ||

| lower/no | 427 | 62 | 208 | 61 | 202 | 62 | 17 | 68 | ||

| Physical activity | 0.275 | |||||||||

| As before | 190 | 28 | 100 | 29 | 85 | 26 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Lower | 283 | 41 | 129 | 38 | 143 | 44 | 11 | 44 | ||

| Upper | 152 | 22 | 71 | 21 | 73 | 22 | 8 | 32 | ||

| Never | 64 | 9 | 39 | 12 | 24 | 8 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Weight gain | 0.436 | |||||||||

| Yes | 258 | 37 | 119 | 35 | 124 | 38 | 15 | 24 | ||

| Unknown | 109 | 16 | 56 | 17 | 50 | 15 | 3 | 12 | ||

| No | 322 | 47 | 164 | 48 | 151 | 47 | 7 | 28 | ||

1Numbers do not add up because there were five respondents who reported another gender (data not shown).

2Kosovo Administrative regions.

3Differences between the three MedDiet adherences groups were evaluated by the Chi-squared test.

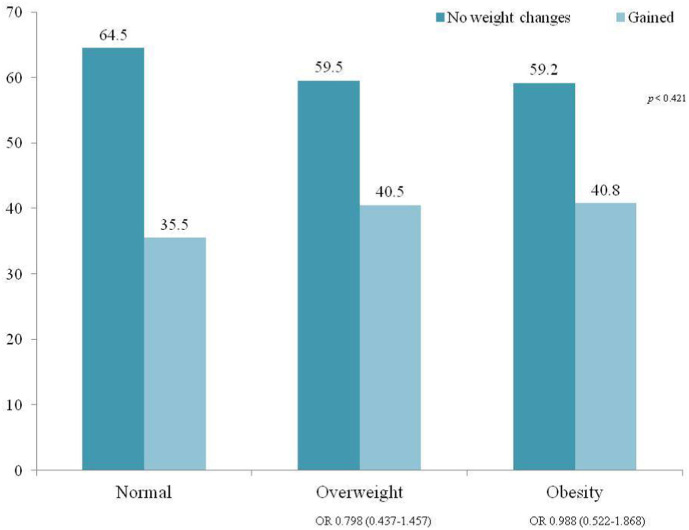

Changes in the MedDiet adherences and association of variables with Body weight Increase.

From the Chi-square test analyses, it is obvious that age, children in care, alcohol intake, fast food frequency, and sweet beverage consumption were significantly associated with adherence to the MeDdiet levels (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 ). According to changes in eating habits (Table 4), the highest percentage of the study sample consumed the same olive oil (67.34%), legumes (75.18%) and higher portions of vegetables (49.6%), and fruits (51.24%) per day as before lockdown. Regarding meat consumption, 47.9% consumed red meat as before, and 71.84% consumed fish as before the lockdown. Also, the highest percentage of participants declared no change in the consumption of non-homemade pastries (43.1%) and sweet beverages (40.34%) that was statistically significant (p < 0.003) (Table 4). Since dietary and lifestyle habits changed, several food choices were associated with the change in weight gain during lockdown (Table 7 ). Multivariate-adjusted models showed that those participants who reported a lower intake of meat (OR: 0.79, 95% IC: 0.65–0.97) during the COVID-19 Kosovo lockdown had a statistically significant higher likelihood of gaining weight because of higher consumption of bakery products compared to those who eat higher meat portion during the lockdown. Similarly, OR associated with weight gain increased significantly in respondents who had a lower intake of pan fried trout fish weekly (OR: 1.04 95% IC: 0.99–1.08). Also, a significantly higher odds (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.21–0.87) of changing, respectively gaining weight during lockdown, compared to those who kept being with lower activity or inactive respondents was found. There was a significant inverse correlation between higher BMI and olive oil intake and obviously weight gain was significantly correlated with eating more during the COVID-19 lockdown than before (data not shown). Table 6 displays multivariate-adjusted ORs associated with the change in adherence to MedDiet in relation to the MEDAS-derived foods, considering mutual adjustment by each other food item. The weight gain was associated with the BMI of participants which means that those with higher BMI gained weight more often compared to those having normal BMI (Fig. 3 ). The logistic regression showed that women were more likely to be associated with higher adherence to MedDiet during the COVID-19 lockdown (Table 6). Similarly Bouzas et al. (2020), reported that women participants had higher desired weight loss, related to higher education levels. Moreover, weight management has been associated with a higher consumption of fruits and vegetables, especially in women (Kuk et al., 2009; Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al., 2009; Romieu et al., 2012; Tsai et al., 2016). No associations were found with age and education of respondents. In multivariate logistic regression analyses, the association of weight gain with the increased intake of fast food, eating more, no physical activity and higher frequency of cooking remained statistically significant. Also, the odds of weight gain also increased with higher pastries intake, higher beverage or sugary drinks, and increased snacking intake. The main strength of this project was the cooperation of scientists from different countries and many disciplines which were widely distributed in several countries. The investigation exceeded the minimum sample size of 385 participants with 5% of margin of error and the confidence of 95% and provides novel results applicable to lockdown times and after. The common limitation in the field of behavioral nutrition research which uses surveys that measures dietary behaviors has relied on self-reported survey studies and the validity of answers is a general problem. The second limitation is its cross-sectional design; and the use of unvalidated measures such as self-reported body weight and physical activity level.

Table 4.

Dietary behaviors relative to the MedDiet pattern during the COVID-19 Kosovo lockdown.

| MEDAS Food | All |

Low |

Medium |

High |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 689) | (N = 339) | (N = 325) | (N = 25) | p-Value | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Olive Oil | 0.402 | |||||||||

| As before | 464 | 67 | 218 | 64 | 229 | 70 | 17 | 68 | ||

| Lower | 67 | 10 | 37 | 11 | 29 | 9 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Higher | 158 | 23 | 84 | 25 | 67 | 21 | 7 | 28 | ||

| Vegetables | 0.835 | |||||||||

| As before | 318 | 46 | 159 | 47 | 148 | 45 | 11 | 44 | ||

| Lower | 29 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Higher | 342 | 50 | 168 | 50 | 162 | 50 | 12 | 48 | ||

| Fruits | 0.739 | |||||||||

| As before | 293 | 43 | 136 | 40 | 150 | 46 | 7 | 28 | ||

| Lower | 43 | 6 | 23 | 7 | 18 | 6 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Higher | 353 | 51 | 180 | 53 | 157 | 48 | 16 | 64 | ||

| Red Meat | 0.121 | |||||||||

| As before | 324 | 48 | 151 | 44 | 158 | 49 | 15 | 60 | ||

| Lower | 261 | 37 | 144 | 43 | 112 | 34 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Higher | 104 | 15 | 44 | 13 | 55 | 17 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Sweet Beverages | 0.003 | |||||||||

| As before | 278 | 40 | 124 | 36 | 142 | 44 | 12 | 48 | ||

| Lower | 257 | 37 | 149 | 44 | 101 | 31 | 7 | 28 | ||

| Higher | 154 | 23 | 66 | 20 | 82 | 25 | 6 | 24 | ||

| Legumes | 0.188 | |||||||||

| As before | 518 | 75 | 253 | 75 | 247 | 76 | 18 | 72 | ||

| Lower | 74 | 11 | 44 | 13 | 28 | 9 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Higher | 97 | 14 | 42 | 12 | 50 | 15 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Fish | 0.102 | |||||||||

| As before | 495 | 72 | 243 | 72 | 235 | 72 | 17 | 68 | ||

| Lower | 121 | 18 | 67 | 20 | 51 | 16 | 3 | 12 | ||

| Higher | 73 | 10 | 29 | 8 | 39 | 12 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Non- homemade Pastries | 0.128 | |||||||||

| As before | 297 | 43 | 132 | 39 | 153 | 47 | 12 | 48 | ||

| Lower | 153 | 22 | 87 | 26 | 61 | 19 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Higher | 239 | 35 | 120 | 35 | 111 | 34 | 8 | 32 | ||

Differences between the MedDiet adherence groups (low. medium and high) were evaluated by the Chi-squared test.

Table 7.

The proportion of participants changes in health behaviours by changes in weight (%) and Odds Ratios (OR) for the likelihood of weight gain.

| Logistic regression |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gained | No Changes/Doesn't Know | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Sex | 1.02 (0.72–1.43) | 0.921 | |||

| Male | 31.1 | 28.5 | – | ||

| Female | 68.9 | 71.3 | – | ||

| Another | 0 | 0.2 | |||

| Meat ratio | 0.67 (0.50–0.94) | 0.030 | |||

| Under 1 | 58.4 | 67.1 | 1.15 (1.02–1.31) | 0.021 | |

| Upper | 41.6 | 32.9 | 0.79 (0.65–0.97) | – | |

| Fish ratio | 1.95 (0.99–3.82) | 0.058 | |||

| Upper 3 | 7.4 | 3.9 | 0.53 (0.28–1.01) | 0.049 | |

| Under | 92.6 | 96.1 | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | – | |

| Olive oil | 0.80 (0.59–1.09) | 0.791 | |||

| Lower | 10.9 | 9 | 1 | – | |

| No change | 70.8 | 65.3 | 1.21 (0.59–2.45) | 0.602 | |

| Higher | 18.3 | 25.7 | 1.19 (0.71–1.99) | 0.500 | |

| Vegetable | 1.17 (0.87–1.57) | 0.771 | |||

| Lower | 3.1 | 4.9 | 1 | – | |

| No change | 44 | 47.5 | 0.77 (0.32–1.89) | 0.578 | |

| Higher | 52.9 | 47.7 | 0.90 (0.63–1.28) | 0.567 | |

| Pasta | 1.11 (0.89–1.39) | 0.366 | |||

| Lower | 17.5 | 25 | 1 | – | |

| No change | 48.2 | 40 | 0.76 (0.44–1.29) | 0.311 | |

| Higher | 34.2 | 35 | 1.13 (0.76–1.67) | 0.537 | |

| Fish | 0.602 | ||||

| Lower | 20.6 | 16.7 | 1 | – | |

| No change | 67.7 | 73.1 | 1.08 (0.60–1.95) | 0.778 | |

| Higher | 11.7 | 10.2 | 0.88 (0.52–1.47) | 0.637 | |

| Beverage Sweet | 0.229 | ||||

| Lower | 32.7 | 40 | 1 | – | |

| No change | 44.7 | 37.7 | 0.80 (0.52–1.21) | 0.301 | |

| Higher | 22.6 | 22.2 | 1.10 (0.72–1.67) | 0.645 | |

| Physical activity | 0.000 | ||||

| No change | 18.3 | 33.1 | 1 | ||

| Lower | 52.9 | 34.0 | 0.38 (0.19–0.77) | 0.007 | |

| Higher | 16.7 | 25.2 | 0.87 (0.45–1.65) | 0.667 | |

| No activity | 12.1 | 7.6 | 0.43 (0.21–0.87) | 0.020 | |

| Fast Food | 0.023 | ||||

| No change | 28.4 | 39.4 | 1 | ||

| Lower | 47.9 | 53.0 | 0.42 (0.22–0.79) | 0.007 | |

| Higher | 23.7 | 7.6 | 0.49 (0.28–0.88) | 0.017 | |

| Snack Eating | No change | 35.4 | 50.7 | 1 | 0.171 |

| Lower | 19.5 | 20.6 | 0.91 (0.58–1.40) | ||

| Higher | 45.1 | 28.7 | 1.52 (0.87–2.63) | ||

| Frequent cooking | 0.92 (0.76–1.10) | 0.009 | |||

| No change | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1 | ||

| Lower | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.85 (0.55–1.31) | ||

| Higher | 54.9 | 49.5 | 2.90 (1.37–6.11) | ||

| Often Eating | 0.000 | ||||

| No | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.10 (0.06–0.16) | ||||

Fig. 3.

Association between body mass index (BMI) of the participants and weight gain during the lockdown (%).

4. Conclusion

This is the first study targeted on assessment of changes in eating behavior in a Kosovo adult population during the COVID-19 lockdown. Overall, our results highlighted that most participants decreased unhealthy nutritional behaviors and physical activity level during the lockdown. Furthermore, the majority of participants increased fruits and vegetable consumption and cooking frequency being boiling the main employed technique. The weight gained during the lockdown presented positive association with the higher frequency of cooking than before the lockdown started. However, the present study is considered as a preliminary description of the assessment of nutritional status and identification of potential risk factors of the negative eating behaviors highlighted the importance with intention of making possible nutritional intervention for healthy lifestyle improving. Our intention is to highlight the need for better promotion of general well-being with future studies assessing maintains after the lockdown.

Author contributions

ES analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. AH and GXh collected the data while CRP designed the data and provided critical feedback on the manuscript. All authors read and ensured input on the manuscript before approving.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Committee of the University of Granada. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Declarations of competing interest

None.

Ethics

The international COVIDiet study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Granada (1526/CEIH/2020). Additionally, the Kosovo study was approved by the Bioethics Centre of the University of Tetova. This study is anonymous and it follows the existing regulations regarding Confidentiality and Data Protection Policy (Spanish Organic Law of Personal Data Protection (LOPD) 15/1999). The following questionnaire is addressed to the adult citizens of Kosovo, who by answering the questions provide their consent for their voluntary participation in the study. The questionnaire has been translated to 14 different languages and the study is being conducted in 18 countries simultaneously.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants in the present study. We thank the Head of Project Management Office of the University of Tetova: Gjeraqina Leka and administrative team of the international COVIDiet survey, the AGR-141 research group: Celia Rodríguez-Pérez, Esther Molina-Montes, Vito Verardo, Reyes Artacho, Belén García-Villanova,Eduardo Jesús Guerra- Hernández and Maria Dolores Ruíz-López from the Department of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Granada, Spain, for sharing COVIDiet questionnaire.

References

- Ammar A., Brach M., Trabelsi K., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L., Bouaziz B., Bentlage E., How D., Ahmed M., Müller P., Müller N., Aloui A., Hammouda O., Paineiras-Domingos L.L., Braakman-Jansen A., Wrede C., Bastoni S., Pernambuco C.S., Hoekelmann A. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB- COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1583. doi: 10.3390/nu12061583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anne K., Ekaterini G., Falk K., Thomas H. Did the general population in Germany drink more alcohol during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown? Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agaa058. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby N.J.S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on unhealthy eating in populations with obesity. Obesity, oby. 2020:22940. doi: 10.1002/oby.22940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventura P., Benedetti G., Albarède F., Miossec P. Zinc and its role in immunity and inflammation. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2015;14:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzas C., Bibiloni M.d.M., Julibert A., Ruiz-Canela M., Salas-Salvadó J., Corella D., Zomeño M.D., Romaguera D., Vioque J., Alonso-Gómez Á.M., Wärnberg J., Martínez J.A., Serra-Majem L., Estruch R., Tinahones F.J., Lapetra J., Pintó X., García Ríos A., Bueno-Cavanillas A.…Tur J.A. Adherence to the Mediterranean lifestyle and desired body weight loss in a Mediterranean adult population with overweight: A PREDIMED- Plus study. Nutrients. 2020;12:2114. doi: 10.3390/nu12072114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/c5pz8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanini M.Z., Guallar-Castillón P., Rodríguez-Artalejo F., Lopez-Garcia E. Mediterranean diet and changes in sleep duration and indicators of sleep quality in older adults. Sleep. 2017;40:zsw083. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll N., Sadowski A., Laila A., Hruska V., Nixon M., Ma D.W.L., Haines J. The impact of COVID-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food securityamong middle to high income Canadian families with young children. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2352. doi: 10.3390/nu12082352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzo A., Bernardini S., Gualtieri P., Cabibbo A., Perrone M.A., Giambini I., Di Renzo L. Mediterranean meal versus western meal effects on postprandial ox-LDL, oxidative and inflammatory gene expression in healthy subjects: A randomized controlled trial for nutrigenomic approach in cardiometabolic risk. Acta Diabetologica. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00592-016-0917-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschasaux-Tanguy M., Druesne-Pecollo N., Esseddik Y., de Edelenyi F.S., Alles B., Andreeva V.A., et al. Diet and physical activity during the COVID-19 lockdown period (March–May 2020) MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.04.20121855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo L., Gualtieri P., Pivari F., Soldati L., Attinà A., Cinelli G., Cinelli G., Leggeri C., Caparello G., Barrea L., Scerbo F., Esposito E., De Lorenzo A. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2020;18(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo L., Gualtieri P., Romano L., Marrone G., Noce A., Pujia A., et al. Role of personalized nutrition in chronic-degenerative diseases. Nutrients. 2019 doi: 10.3390/nu11081707. MDPI AG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone D., Frøst M.B., Rodríguez-Pérez C. Reported changes in dietary habits during the Covid-19 lockdown in the Danish population: The Danish COVIDiet study. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2020;7:294. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.592112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosovo Government 2020. https://kryeministri-ks.net/en/konfirmohen-dy-rastet-e-para-te-corona-virusit-covid-19-ne-kosove/

- Kosovo Government 2020. https://kryeministri-ks.net/en/the-kosovo-government-holds-its-15th-meeting/

- Kriaucioniene V., Bagdonaviciene L., Rodríguez-Pérez C., Petkeviciene J. Associations between changes in health behaviours and body weight during the COVID-19 quarantine in Lithuania: The Lithuanian COVIDiet study. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):3119. doi: 10.3390/nu12103119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk J.L., Ardern C.I., Church T.S., Hebert J.R., Sui X., Blair S.N. Ideal weight and weight satisfaction: Association with health practices. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:456–463. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp135. https://doi:10.1093/aje/kwp135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González M.A., García-Arellano A., Toledo E., Salas-Salvadó J., Buil-Cosiales P., Corella D., Covas M.I., Schröder H., Arós F., Gómez-Gracia E., et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: ThePREDIMED trial. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043134. https://doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini M., Ponzo V., Rosato R., Scumaci E., Goitre I., Benso A., Belcastro S., Crespi C., De Michieli F., Ghigo E., Broglio F., Bo S. Changes in weight and nutritional habits in adults with obesity during the “lockdown” period caused by the COVID-19 virus emergency. Nutrients. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/nu12072016. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobelli A., Pecoraro L., Ferruzzi A., Heo M., Faith M., Zoller T., Antoniazzi F., Piacentini G., Fearnbach S.N., Heymsfield S.B. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: A longitudinal study. Obesity. 2020;28(8):1382–1385. doi: 10.1002/oby.22861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Olavarría D., Latorre-Román P.Á., Guzmán-Guzmán I.P., Jerez-Mayorga D., Caamaño-Navarrete F., Delgado-Floody P. Positive and negative changes in food habits, physical activity patterns, and weight status during COVID-19 confinement: Associated factors in the Chilean population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17:5431. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pérez C., Molina-Montes E., Verardo V., Artacho R., García-Villanova B., Guerra Hernández E.J., Ruíz-López M.D. Changes in dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet Study. Nutrients. 2020;12:1730. doi: 10.3390/nu12061730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez E., Aparicio A., López-Sobaler A.M., Ortega R.M. Body weight perception and dieting behaviour in Spanish population. Nutricion Hospitalaria. 2009;24:580–587. doi: 10.3305/nh.2009.24.5.4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu I., Escamilla-Núñez M.C., Sánchez-Zamorano L.M., Lopez-Ridaura R., Torres-Mejía G., Yunes E.M., Lajous M., Rivera-Dommarco J.A., Lazcano-Ponce E. The association between body shape silhouette and dietary pattern among Mexican women. Public Health Nutrition. 2012;Vol. 15:116–125. doi: 10.1017/s1368980011001182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidor A., Rzymski P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1657. doi: 10.3390/nu12061657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springmann M., Wiebe K., Mason-D’Croz D., Sulser T.B., Rayner M., Scarborough P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: A global modeling analysis with country- level detail. Lancet Planetry Health. 2018;2:e451–e461. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30206-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S.A., Lv N., Xiao L., Ma J. Gender differences in weight-related attitudes and behaviors among overweight and obese adults in the United States. American Journal of Men's Health. 2016;10:389–398. doi: 10.1177/1557988314567223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USA Government 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html

- Vieux F., Perignon M., Gazan R., Darmon N. Dietary changes needed to improve diet sustainability: Are they similar across Europe? European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2018;72:951–960. doi: 10.1038/s41430-017-0080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report on a WHO consultation. Report No. 894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]