Abstract

The rhizosphere microbial community is important for plant health and is shaped by numerous environmental factors. This study aimed to unravel the effects of a pesticide/fertilizer mixture on the soil rhizosphere microbiome of field-grown sugarcane. A field trial on sugarcane was conducted in Zhanjian City, Guangdong Province, China, and soil samples from the rhizosphere were collected after clothianidin pesticide and/or organic fertilizer treatments. The effects of pesticide and/or organic fertilizer treatments on the composition, diversity, and predictive function of the rhizosphere microbial communities were examined using 16S rRNA gene and ITS1 amplicon sequencing. Compared with the controls (no pesticide or fertilizer used), the microbial community that resulted from treatment with the pesticide/fertilizer mixture (SPF) had a higher relative bacterial diversity and fungal richness, and contributed more beneficial functions to sugarcane, including xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism of amino acids. The bacterial and fungal compositions at various taxonomic levels were not significantly different in SPF and SP (pesticide only) treatments compared to treatments without the pesticide, suggesting that the clothianidin addition did not cause a detrimental impact on the soil microbiome. Moreover, five bacterial genera, including Dyella, Sphingomonas, Catenulispora, Mucilaginibacter, and Tumebacillus, were significantly more abundant in the SPF and SP treatments, which could be associated with the pesticide addition. With the addition of organic fertilizers in SPF, the abundances of some soil-beneficial bacteria Bacillus, Paenibacillus, and Brevibacillus were highly increased. Our study provides insights into the interactions between the rhizosphere soil microbiome and pesticide-fertilizer integration, which may help improve the application of pesticide-fertilizer to sugarcane fields.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-021-02770-3.

Keywords: Sugarcane, Soil microbial community, Pesticide-fertilizer combinations, Amplicon sequencing

Introduction

Sugarcane has become the most important cash crop in southern China. Sugarcane crops suffer from various pests at different developmental stages and require a significant amount of pesticides and fertilizers to sustain their growth and health (Franco et al. 2011; Cherry et al. 2017). However, the heavy use of pesticides and fertilizers in sugarcane cultivation has caused severe impacts on the agricultural environment, including pollution, increased cultivation costs, excessive energy consumption, and effects on beneficial invertebrates as well as threats to food safety and quality (Bokhtiar and Sakurai 2005; Klaine et al. 1988; Velasco et al. 2012). In 2015, China's Ministry of Agriculture introduced two actions to stop the increase in the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides by 2020 (Jin and Zhou 2018). This is urgently needed to promote the improvement of pesticide/fertilizer-related products and effectively protect the agroecological environment.

Pesticide/fertilizer combinations (SPF) or mixture products are popular and are increasingly applied to farmland, as they serve a dual purpose with both nutritional and insecticidal characteristics, which could help achieve complete SPF integration and reduce labor and costs (Achorn and Wright 1982; Xie et al. 2017, 2019). Tiange, for instance, is a popular multifunctional SPF product used in sugarcane cultivation in southern China and can effectively suppress pests including the sugarcane borer, thrip, aphid, and cockchafer (Xie et al. 2017). Xie et al. (2019) found that the pesticide blended 50–50 with a fertilizer solution can alleviate nutrient loss and promote tea yield and quality. Yein et al. (2013) reported that integrating pesticides and fertilizers were much more effective at controlling root-knot nematodes infesting mung beans than pesticide or fertilizer alone.

The rhizosphere microbial community has been described as not only crucial for soil fertility but also essential in crop productivity and disease suppression (Haney et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2020; Korenblum et al. 2020). However, research on the effects of SPF on the rhizosphere microbial diversity and function of sugarcane is still rare. Currently, the overuse of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides has been reported to cause adverse effects on the soil microflora, and can substantially affect crop productivity (Hartmann et al. 2015; Zhu et al. 2016). In particular, some chemical fertilizers and pesticides can persist in soil for a long time, which threatens the balance of the soil microbial structure and consequently decreases soil health and quality (Prashar and Shah 2016).

In this study, we hypothesized that pesticide inputs supplemented with organic fertilizer could maintain the composition of the soil microbiome more sustainably than the conventional method based on applying the pesticide and fertilizer separately. Here, we conducted a field experiment to reveal any shifts in the rhizosphere microbiome with different pesticide and/or fertilizer treatments as well as to compare treatment effects on the structure and function of the soil microbiome. The objectives of this study were to: (1) investigate the effects of an SPF on the structure and diversity of the rhizosphere microbiome of sugarcane; and (2) assess the potential interactions between a reduction in the use of both pesticide and fertilizer.

Materials and methods

Experimental designs

The SP1308 product was the SPF used in this study and is applied widely in a sugarcane field in Guangdong Province. SP1308 contains two main components: clothianidin, which is a pesticide, and an animal-derived amino acid solution used as a bio-fertilizer. SP1308 contains 1% clothianidin (AccuStandard Company, USA), organic fertilizer (amino acid solution mostly including animal hair protein, 64 mL/kg), and excipients (aminocellulose 30 g/kg, gelatin 20 g/kg, and kaolin 940 g/kg, which are all produced by Damao Company, Tianjin, China). Clothianidin ((E)-1-(2-chloro-1,3-thiazol-5-ylmethyl)-3-methyl-2- nitroguanidine) is a second-generation neonicotinoid insecticide. It is a white crystalline compound with a molecular weight of 249.68 and has the lowest water solubility (0.327 g/L) among the neonicotinoids (Hirano et al. 2015). Here, we chose clothianidin as the pesticide study object due to its broad-spectrum activity, it is readily biodegradable and has high safety for crops (Uneme 2011; Endres et al. 2016).

The experimental design comprised five treatments: (1) SPF (pesticide and fertilizer mixed with excipient), (2) a pesticide control (SP, pesticide mixed with excipient, but with no fertilizer added), (3) a fertilizer control (SF, fertilizer mixed with excipient, but with no pesticide added), (4) an excipient control (SA, with neither pesticide nor fertilizer added), and (5) one control blank (SK). There were four replicates for each treatment.

Field experiment, sampling, and DNA extraction

The field experiment was performed in a field plot located in Suixi County, Zhanjiang City of Guangdong Province (21°14′23′′N, 110°4′28′′E; average altitude 20 ~ 45 m; average annual precipitation 1759.4 mm; average annual temperature 21 ~ 28 °C) to investigate the impact of clothianidin with and without fertilizer on the structure of microbial communities in the rhizosphere soil. When the sugarcane seedlings grew to have 3 ~ 5 leaves, we started the field experiment including the four treatments SPF, SP, SF, and SA with 100 g of each spread into the soil close to the sugarcane in each plot (7.4 × 1.8 m in size), and a thin layer of soil applied to cover it. Each treatment consisted of 4 plots, with one meter between each plot, as well as a blank control.

After 3 weeks, rhizosphere soil samples were collected from the sugarcane plots. For the rhizosphere soil samples, 3 ~ 5 plants per plot with the complete root systems intact were combined as a composite sample to remove loosely adhering soil by vigorous shaking. Twenty composite samples deposited in sterile plastic zipper bags were stored in the lab with ice. Roots with soil on the surface were washed twice with a sterile 1 × PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) solution (Solarbio Life Sciences, China), and then centrifuged at 8000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting pellets, defined as the rhizosphere-enriched microbial communities, were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for microbial DNA isolation. The detailed methods for DNA extraction were described in our previous study (Huang et al. 2020).

High-throughput amplicon sequencing

Amplicon sequencing of the bacterial and fungal rhizosphere communities for the 20 soil samples was conducted for the 16S rRNA gene and ITS1 region, respectively, using the Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Commonly used primers, (515F, 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG-3′ and 806R, 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) were used for PCR to amplify the V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene. PCR primers for amplification of the fungal ITS1 region were ITS1-1737F, 5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCG TAACAAGG-3′, and ITS2-2043R, 5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′. PCR reactions were carried out following the protocols described by Huang et al. (2020). All high-throughput sequencing and library generation were conducted by Novogene Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The metagenome sequences of all samples were uploaded to the NCBI SRA database with the accession numbers SUB7134467 and SUB7134514.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

Quality filtering on the raw reads was performed to obtain clean reads based on the process of Cutadapt (V1.9.1, http://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/) (Martin 2011) quality control. The reads were compared with the reference database (SILVA database, https://www.arb-silva.de/) 20 using the UCHIME algorithm (http://www.drive5.com/usearch/manual/uchime_algo.html) (Edgar et al. 2011) to detect chimeric sequences, and then the chimeric sequences were removed. Sequence analysis was performed using Uparse software (Uparse v7, http://drive5.com/uparse/) (Edgar 2013). Sequences with ≥ 97% similarity were assigned to the same operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (DeSantis et al. 2006). Representative sequences for each OTU were screened for further annotation using the SILVA database (https://www.arb-silva.de/) for bacteria and with the UNITE database (v7.2) (https://unite.ut.ee/) (Nilsson et al. 2019) for fungi. Alpha diversity and beta diversity were then calculated with QIIME (Version1.9.1) (Caporaso et al. 2011) and displayed with R software (Version 2.15.3). Principal coordinate analyses (PCoA) were displayed using the WGCNA package, stat packages, and ggplot2 package in R. Based on species information obtained from amplicon analysis, the ecological functions of bacterial and fungal communities were predicted using the PICRUSt (Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States) (Langille et al. 2013) and FUNGuild databases (Nguyen et al. 2016), respectively. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the post-hoc test with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Bacterial and fungal richness and diversity

For the entire sampling set, a total of 1,353,140 bacterial sequences (raw tags) with an average length of 253 bp and 1,150,116 fungal sequences with an average length of 240 bp were identified. As a result of chimera filtration and quality control, 1,279,641 bacterial and 1,101,677 fungal high-quality sequences (clean tags) were obtained (Appendix S1 and S2). The total number of 16S and ITS reads were obtained from 18 and 14 soil samples, respectively, with two and six samples not successfully sequenced. The phylogenetic relationships of more than 500 bacterial and 200 fungal genera were identified in the SPF-treated rhizosphere soil (Appendix Figure S1). Rarefaction curves of all samples tended to be flat, suggesting that a reasonable sequencing depth was attained, although some very rare bacterial taxa are likely present in samples (Appendix Figure S2).

Shannon and Chao1, the community richness indices, showed that the bacterial diversity of SPF-treated rhizosphere soil was significantly higher than that of SP-treated and control soil (SK) (p < 0.05, Fig. 1a, b). Alpha diversity in the SF treatment was significantly increased compared to that in the SP treatment (p < 0.05). In addition, the α diversity of the excipient treatment (SA) was investigated and showed a distinct increase compared with that in SP and SK treatments (p < 0.05). It is likely that the excipients added to SPF, SP, and SF did not decrease the diversity of the rhizosphere bacterial community of sugarcane. For fungal diversity, the Shannon and Chao1 indices of the SPF-treated soil were the highest (p < 0.05, Fig. 1c, d), followed by SF and SP, and lastly SA treatment.

Fig. 1.

Alpha-diversity of the bacterial and fungal communities for five treatments of microbial samples. a, b, representing Shannon diversity and Chao1 of the bacterial community; c, d, representing Shannon diversity and Chao1 of the fungal community. SPF a pesticide and fertilizer mixed with excipient, SP a pesticide mixed with excipient, but with no fertilizer added, SF,= fertilizer mixed with excipient, but with no pesticide added, SA an excipient control, with neither pesticide nor fertilizer added, SK one control blank. Significances between different groups were compared using Wilcoxon’s test, with the results indicated on the top (p value ≤ 0.05 = *, p value ≤ 0.01 = **)

According to the PCoA plots, the bacterial community structure of the SPF treatment was separated from the other treatments by PCo1 (49.88%) and PCo2 (19.15%) (Fig. 2a). The PCoA analysis, based on weighted UniFrac metrics, placed the bacterial community of SPF-treated soil much closer to those of the SP- and SF- treated soil, while that of SK was distantly placed. Beta diversity between the five treatments also demonstrated that there were significant differences in bacterial community structure between SPF and SP, SP and SA, and SP and SK (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon test, Appendix Figure S3a). In addition, Adonis (permutational MANOVA) showed that there were significant differences in bacterial communities between SP and SF (R2 = 6.87, p < 0.05). The fungal community of each treatment was separated by PCo1 (78.44%) and PCo2 (5.52%) based on the weighted UniFrac analysis (Fig. 2b). The fungal community structure of SPF was similar to that of SP, but significantly distinct from that of SF (p < 0.05, Appendix Figure S3b).

Fig. 2.

Beta diversity of the microbial community using PCoA analysis with the weighted_Unifrac metric. a beta diversity of the bacterial community; b beta diversity of the fungal community. Symbols represent different treatments. Each point represents a sample

Microbial community composition and structure

Across all treatments, the dominant bacterial phyla (> 4% in any sample) in the rhizosphere bacterial community were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, and Bacteroidetes (Fig. 3a). These phyla were represented in all treatments though with different relative abundances. Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria had the highest number of reads in each rhizosphere, together making up at least 60% of the total bacterial population in each set of samples. The main effects of pesticide and fertilizer addition on the bacterial community composition of sugarcane and the interactions between them were studied using PERMANOVA analysis. The addition of pesticide (SP) or fertilizer (SF) had a significant effect on the bacterial community (p < 0.05), i.e., the phylum Actinobacteria was significantly increased in SP (43.0%) compared with that in SF (16.5%) (p < 0.01), and the phylum Proteobacteria was significantly increased in SF (48.1%) compared with that in SP (23.2%) (p < 0.05) (Appendix Figure S4a).

Fig. 3.

Taxonomic differences in bacterial community among the five treatments. a relative abundance of the top 10 phyla; b relative abundance of the top 10 families; c, relative abundances of the top 20 genera were compared among different treatments

At the family level, the bacterial communities in all treatments were dominated by Burkholderiaceae, Moraxellaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Streptomycetaceae, Micrococcaceae, Bacillaceae, and Enterobacteriaceae (Fig. 3b). The relative abundance of many families varied greatly among treatments, especially in SP and SF. The abundance of Micrococcaceae and Streptomycetaceae in SP was significantly increased compared to in SF (p < 0.01), while Moraxellaceae and Bacillaceae were significantly increased in SF compared to in SP (p < 0.01) (Appendix Figure S4b). Variation in family abundance in SPF was more likely affected by both SP and SF addition.

In the top 20 genera, the dominant genera were notably different among treatments. The abundances of Dyella, Chryseobacterium, Lysinibacillus, and Acidothermus in SPF were significantly greater than those in other treatments (p < 0.05, Fig. 3c). The abundances of Conexibacter, Leifsonia, Chujaibacter, Sinomonas, and Acidipia in the SP treatment were significantly greater than those of the SA (excipient addition) and SK (blank control) treatments (p < 0.05).

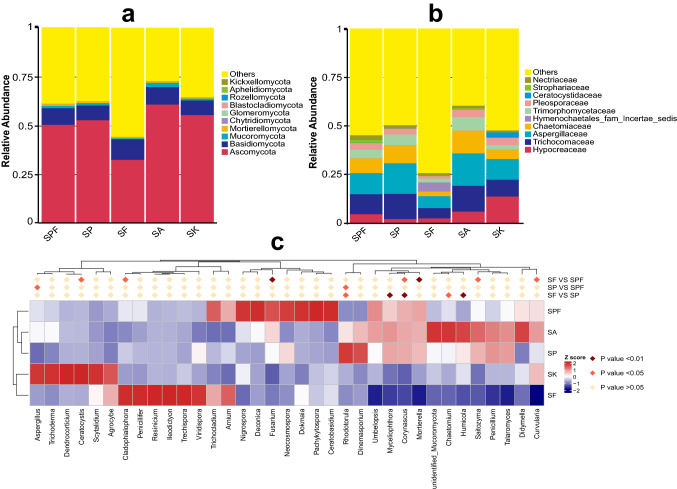

The dominant fungal phyla across all the treatments were Ascomycota, followed by Basidiomycota and Mucoromycota (Fig. 4a). Among the top ten phyla, Mortierellomycota, Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, Blastocladiomycota, Rozellomycota, Aphelidiomycota, and Kickxellomycota were the least abundant (< 1%). As shown in Fig. 4b, the relative abundances of fungal families diverged significantly among different treatments. In particular, the relative abundance of Chaetomiaceae was greatly increased in SP compared with that in SF (p < 0.01, Appendix Figure S4c). In the top 20 genera, the fungal community of the SPF treatment was dominated by Penicillium (10.4%), Talaromyces (10.3%), Trichoderma (4.7%), and Myceliophthora (4.4%) (Fig. 4c). Compared with other treatments, using ANOVA analysis, the abundances of Nigrospora, Deconica, Fusarium, Neocosmospora, Dokmaia, Pachykytospora, and Ceratobasidium showed a significant increase in SPF (p < 0.05). The abundances of Mycelliophthora, Corynascus, and Mortierella both in the SPF and SP treatments were much higher than those in the SF treatment (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Taxonomic differences in fungal community among the five treatments. a relative abundance of the top 10 phyla; b relative abundance of the top 10 families; c relative abundance of the top 20 genera were compared among different treatments

Functional potentials of the rhizosphere microbial community

Bacterial functional profiles were assessed using 16S rRNA gene data (Appendix S3) through PICRUSt software. Differences in the putative function of the bacterial community between the control and test treatments were observed with strong segregation (Fig. 5a, Appendix S4). Biological functions were found to be significantly more abundant in the SPF treatment than in the SK treatment (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Through comparisons of the bacterial functions in the SPF and SP treatments using a t test, we found that SPF exhibited significantly higher xenobiotic biodegradation and metabolism functions (p < 0.05) (Appendix Figure S5a). SPF had significantly increased functions for metabolism compared to those of SF (p < 0.05) and SA (p < 0.05) (Appendix Figures S5b and c). As the only difference between the SP and SF treatments was clothianidin, the different microbial functions caused by clothianidin were observed, mainly including carbon fixation, glycolysis, butanoate metabolism, and methane metabolism (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Functional prediction profiling of microbial community among the five treatments. a predictive functions of the bacterial community using PICRUSt; b annotation of fungal community using mode; c, annotation of fungal community using Guild

A total of 1494 fungal OTUs (Appendix S5) were assigned to the functions of fungal communities based on the FUNGuild database. At least eight trophic modes were detected in this study, among which the saprotroph mode was the most abundant, followed by pathotroph, pathotroph-saprotroph, pathotroph-saprotroph-symbiotroph, and symbiotroph (Fig. 5b, Appendix S6). Sequences annotated with the saprotroph, pathotroph-saprotroph, and pathotroph-symbiotroph modes were significantly decreased in the SPF treatment (p < 0.05) than those in the SK and SA treatments. The most abundant guilds were saprotrophs, followed by plant pathogens, soil saprotrophs, and wood saprotrophs (Fig. 5c, Appendix S7). The relative abundance of fungal functions also differed significantly between treatments. Specifically, SPF had a significantly higher abundance of soil saprotrophs and wood saprotrophs compared to those of the other treatments (p < 0.05). However, SA and SK had significantly higher abundances of plant pathogens (p < 0.05) than those in SPF (Fig. 5c).

In each 16S library, the abundance of functional genes associated with nitrogen cycling, including nifB, nifH, nifU, and nirZ, was predicted (Appendix Figure S6, Appendix S8). The relative abundance of these four genes in the SPF treatment showed no significant difference compared to those of other treatments, indicating that the nitrification capacity of the soil was not affected by the addition of pesticides, fertilizers, or excipients. We also found that the SF treatment significantly improved the abundance of beneficial soil bacteria Bacillus and Paenibacillus compared with those of the SA and SP treatments which do not have added fertilizer (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6). Brevibacillus was also highly enriched in the SF treatment compared with that in the SA, SK, and SP treatments (p < 0.01).

Fig. 6.

Abundance of some representative soil beneficial bacteria in the five treatments (p value ≤ 0.05 = *, p value ≤ 0.01 = **). a genus Bacillus, b genus Paenibacillus, and c genus Brevibacillus

Discussion

Evaluating the toxicological or ecological impacts of agrochemical compounds before they are widely used in agriculture is important for environmental protection (Schmitz et al. 2014). The pesticide/fertilizer mixture in our study is an agrochemical compound widely used on sugarcane seedlings in South China, and its principal components are a pesticide (clothianidin, a chemical compound) and organic fertilizer. However, research on its impact on the soil microbiome of sugarcane is still rare. Here, we conducted 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing to detect disturbances in the diversity and structure of the rhizosphere microbiome under different pesticide and/or fertilizer combinations. The alpha diversity of the bacterial community in the SA treatment (an excipient control with neither pesticide nor fertilizer added) was not significantly different to that of the SPF (pesticide/fertilizer mixture) and SF (fertilizer only) treatments, although revealed a greater diversity than that of SP (pesticide only) (Fig. 1a, b). Moreover, the SA treatment showed significantly higher alpha diversity compared to the SK treatment (control blank) (Fig. 1a, b). This suggests that the common excipients used here could have a favorable or at least non-detrimental effect on the diversity of the soil microbial community. The fungal diversity was the greatest in the SPF (Fig. 1c, d), which was in accordance with a previous study showing an increase in fungal abundance with clothianidin mixture application on soil (Diez et al. 2017), and another study showing a decreased relative abundance of potentially pathogenic fungi with the addition of organic matter (Sun et al. 2016). These results indicate that the pesticide and organic fertilizer addition could influence the diversity of the soil microbial community in a predictable way.

The bacterial and fungal compositions at the various taxonomic levels affected by same percentage of clothianidin in the SPF and SP treatments were not significantly different from those in the other treatments (Figs. 3 and 4), suggesting that clothianidin addition did not cause a detrimental impact on the soil microbiome. Previous reports also demonstrated that treatment of neonicotinoid insecticides on crops did not negatively affect the rhizosphere microbial community (Zhang et al. 2016; Li et al. 2018). In addition, clothianidin treatment on other organisms such as bumblebee did not affect their pathogenic or beneficial microbiota (Wintermantel et al. 2018). Clothianidin granules and pesticide fertilizers with a single high-dose administration applied on cabbage were also reported to be safely used (Zhang et al. 2018). Therefore, our study suggested that an appropriated dosage of pesticide/fertilizer on sugarcane in the field would likely have no lasting adverse effects on the soil microbiome.

With the addition of fertilizer, we found that the SPF treatment resulted in more positive biological metabolic functions on the soil environment compared with the SP, including xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism of amino acids displayed in Figs. 5 and S5a. Moreover, the fungal functions revealed by FUNGuild also revealed that there was a much lower proportion of pathotrophs in the SPF-treated soil compared to that of treatments with no fertilizer addition (Fig. 5b). The result was in accordance with a previous report that the addition of organic matter decreased the relative abundance of potentially pathogenic fungi (Sun et al. 2016). It was further investigated to be essential to integrate pesticide/fertilizer mixture clothianidin with an organic fertilizer since clothianidin is mobile in soil system, however this can be reduced by organic amendment application (Singh et al. 2018). In addition, clothianidin mixed with fertilizers of chicken manure, urea, and organic fertilizer, was evaluated in the field and showed no significant difference (Zhang et al. 2018). Thus, the organic fertilizer used in this study may be replaced by other types of fertilizers in agricultural production.

Clothianidin used in this study has been revealed not significantly accumulated in soil (Xu et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2018), and the process of pesticide dissipation occurring in soil is largely attributed to microbes (Doolotkeldieva et al. 2018). Here, we found that the more abundant bacterial genera, including Dyella, Sphingomonas, Catenulispora, Mucilaginibacter, and Tumebacillus, were highly increased in the SPF and SP treatments compared to the control treatment. Among them, Dyella spp. was found to be a highly efficient biphenyl-degrading strain that could accelerate the initial period of the biphenyl bioremediation process (Zhao et al. 2010). The enriched bacteria that resulted from treating with clothianidin may have been stimulated by the pesticide addition or by other factors, whereby the potential mechanism is still unknown. Additionally, due to the clothianidin being easily degradable, this study used a short three-week timeframe for sampling to observe an impact of clothianidin on the soil microbiome.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the effects of a pesticide/fertilizer mixture as well as a mixture of single active compounds on the sugarcane rhizosphere soil microflora in an attempt to understand the possible effects. The results, based on field experiments, revealed that using a pesticide/fertilizer mixture in field-grown sugarcane does not adversely affect the alpha diversity and potential function of the soil microbiome. Moreover, appropriate organic fertilizer usage and pesticide reduction management practices are not only helpful for decreasing the labor cost of sugarcane cultivation but also advantageous in reducing the potential risk of environmental pollution. Therefore, understanding the interactive effects of different fertilizer and pesticide treatments on the rhizosphere microbiome will be extremely helpful in determining a reasonable application scheme for fertilizers and pesticides.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by GDAS' Project of Science and Technology Development (2019GDASYL-0103031), National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFD0201103), China Sugar industry Research System (CARS-170306), and Guangdong Provincial Team of Technical System Innovation for Sugarcane Sisal Hemp Industry (2019KJ104-06).

Author contributions

WH, YA: Designed the work; YL, LC, and DS: Performed the field collections; WH: Performed the laboratory research and analyzed the data; WH, YA: Wrote the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Achorn FP, Wright EB. Production of fertilizer-pesticide mixtures. ASTM Special Technical Publication, USA. 1982;764:18. [Google Scholar]

- Bokhtiar SM, Sakurai K. Effect of application of inorganic and organic fertilizers on growth, yield and quality of sugarcane. Sugar Tech. 2005;7:33–37. doi: 10.1007/BF02942415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, Fierer N, Knight R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry R, Mccray M, Sandhu H. Changes in the relative abundance of soil-dwelling insect pests in sugarcane grown in Florida. J Entomol Sci. 2017;52:169–176. doi: 10.18474/JES16-33.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Keller K, Brodie EL, Larsen N, Piceno YM, Phan R, Andersen GL. NAST: a multiple sequence alignment server for comparative analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Suppl 2):W394–W399. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez MC, Elgueta S, Rubilar O, Tortella GR, Schalchli H, Bornhardt C, Gallardo F. Pesticide dissipation and microbial community changes in a biopurification system: influence of the rhizosphere. Biodegradation. 2017;28:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10532-017-9804-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolotkeldieva T, Konurbaeva M, Bobusheva S. Microbial communities in pesticide-contaminated soils in Kyrgyzstan and bioremediation possibilities. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25:31848–31862. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres L, Oliveira NG, Ferreira VM, Silva JV, Barbosa GV, Sebastião OM. Morphological and physiological response of sugarcane under abiotic stress to neonicotinoid insecticides. Theor Exp Plant Phys. 2016;28:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40626-016-0056-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franco HCJ, Otto R, Faroni CE, André CV, Emídio CAO, Trivelin PCO. Nitrogen in sugarcane derived from fertilizer under Brazilian field conditions. Field Crop Res. 2011;121:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2010.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haney CH, Samuel BS, Bush J, et al. Associations with rhizosphere bacteria can confer an adaptive advantage to plants. Nat Plants. 2015;1:15051. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Frey B, Mayer J, Mäder P, Widmer F. Distinct soil microbial diversity under long-term organic and conventional farming. ISME J. 2015;9:1177. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Yanai S, Omotejara T, et al. The combined effect of clothianidin and environmental stress on the behavioral and reproductive function in male mice. J Vet Med Sci. 2015;77:1207–1215. doi: 10.1292/jvms.15-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WJ, Sun DL, Fu JT, Zhao HH, Wang RH, An YX. Effects of continuous sugar beet cropping on rhizospheric microbial communities. Genes. 2020;11:13. doi: 10.3390/genes11010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SQ, Zhou F. Zero growth of chemical fertilizer and pesticide use: China's objectives, progress and challenges. J Res Ecol. 2018;9:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Klaine SJ, Hinman ML, Winkelmann DA, Sauser KR, Martin JR, Moore LW. Characterization of agricultural nonpoint pollution: pesticide migration in a West Tennessee watershed. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1988;7:609–614. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620070802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korenblum E, Dong YH, Szymanski J, Panda S, Jozwiak A, Massalha H, Meir S, Rogachev I, Aharoni A. Rhizosphere microbiome mediates systemic root metabolite exudation by root-to-root signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:3874–3883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912130117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, An J, Dang Z, Lv H, Pan W, Gao Z. Treating wheat seeds with neonicotinoid insecticides does not harm the rhizosphere microbial community. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0205200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. Embnet J. 2011;17:10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen NH, Song Z, Bates ST, Branco S, Tedersoo L, Menke J, Schiling JS, Kennedy PG. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016;20:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2015.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson RH, Larsson KH, Taylor AFS, et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D259–D264. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashar P, Shah S. Impact of fertilizers and pesticides on soil microflora in agriculture. In: Lichtfouse E, editor. Sustainable agriculture reviews. Sustainable agriculture reviews. Cham: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J, Hahn M, Brühl CA. Agrochemicals in field margins—an experimental field study to assess the impacts of pesticides and fertilizers on a natural plant community. Agr Ecosys Environ. 2014;193:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2014.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NS, Mukherjeem I, Dasm SK, Varghesem E. Leaching of clothianidin in two different Indian soils: effect of organic amendment. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2018;100:553–559. doi: 10.1007/s00128-018-2290-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R, Dsouza M, Gilbert JA, et al. Fungal community composition in soils subjected to long-term chemical fertilization is most influenced by the type of organic matter. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:5137–5150. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uneme H. Chemistry of clothianidin and related compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:2932–2937. doi: 10.1021/jf1024938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco A, Rodríguez J, Castillo R, Ortíz I. Residues of organochlorine and organophosphorus pesticides in sugarcane crop soils and river water. J Environ Sci Heal. 2012;47:833–841. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2012.693864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermantel D, Locke B, Andersson GKS, et al. Field-level clothianidin exposure affects bumblebees but generally not their pathogens. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5446. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07914-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie JJ, Chen YG, Peng DY, Yang CQ, Huang XJ, Wu G, Chen C, Yang JX. Effect of 30% Tiange multifunctional pesticide-fertilizer on sugarcane pests and yield. Asian AgrRes. 2017;7:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Xie S, Feng H, Yang F, Zhao Z, Hu X, Wei C, Liang T, Li HT, Geng YB. Does dual reduction in chemical fertilizer and pesticides improve nutrient loss and tea yield and quality? A pilot study in a green tea garden in Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:2464–2476. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Dyer DG, McConnell LL, Bondarenko S, Allen R, Heinemann O. Clothianidin in agricultural soils and uptake into corn pollen and canola nectar after multiyear seed treatment applications. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2016;35:311–321. doi: 10.1002/etc.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Liu N, Cheng G, Zhang S, Zhou Y, Liang D, Gu Z. Residue and dissipation of clothianidin in rice and soil. Agrochemicals. 2018;5:343–346. [Google Scholar]

- Yein BR, Singh H, Chhabra HK. Effect of pesticides and fertilizers singly and in combination on the root-knot nematode infesting mung. Indian J Nematol. 2013;7:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Wei Y, Mu W, Liu F. Effects of imidacloprid and clothianidin seed treatments on wheat aphids and their natural enemies on winter wheat. Pest Manag Sci. 2016;72:1141–1149. doi: 10.1002/ps.4090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang PW, Wang SY, Huang CL, et al. Dissipation and residue of clothianidin in granules and pesticide fertilizers used in cabbage and soil under field conditions. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7736-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao LJ, Jia YH, Zhou JT, Li A, Chen JF. Dynamics of augmented soil system containing biphenyl with Dyella ginsengisoli LA-4. J Hazard Mater. 2010;179:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Vivanco JM, Manter DK. Nitrogen fertilizer rate affects root exudation, the rhizosphere microbiome and nitrogen-use-efficiency of maize. Appl Soil Ecol. 2016;107:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.