Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the causative agent for the COVID-19 pandemic, which generated more than 1.82 million deaths in 2020 alone, in addition to 83.8 million infections. Currently, there is no antiviral medication to treat COVID-19. In the search for drug leads, marine-derived metabolites are reported here as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. Two hundred and twenty-seven terpene natural products isolated from the biodiverse Red-Sea ecosystem were screened for inhibitor activity against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) using molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations combined with molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area binding energy calculations. On the basis of in silico analyses, six terpenes demonstrated high potency as Mpro inhibitors with ΔGbinding ≤ −40.0 kcal/mol. The stability and binding affinity of the most potent metabolite, erylosides B, were compared to the human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor, lopinavir. Erylosides B showed greater binding affinity towards SARS-CoV-2 Mpro than lopinavir over 100 ns with ΔGbinding values of −51.9 vs. −33.6 kcal/mol, respectively. Protein–protein interactions indicate that erylosides B biochemical signaling shares gene components that mediate severe acute respiratory syndrome diseases, including the cytokine- and immune-signaling components BCL2L1, IL2, and PRKC. Pathway enrichment analysis and Boolean network modeling were performed towards a deep dissection and mining of the erylosides B target–function interactions. The current study identifies erylosides B as a promising anti-COVID-19 drug lead that warrants further in vitro and in vivo testing.

Keywords: drug discovery, marine natural products, molecular docking, molecular dynamics, SARS-CoV-2 main protease, virtual drug screening

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) belongs to the family Coronaviridae (genus Betacoronavirus; subgenus Sarbecovirus) with a viral envelope encapsulating a single-stranded RNA genome. While most coronaviruses infect mammals and birds, the animal host responsible for the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to men has yet to be identified [1,2,3].

The SARS-CoV-2 genome contains 11 genes encoding 29 proteins and peptides (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_045512.2?report=graph). Four proteins constitute the viral structure, including the spike or S protein responsible for binding with the host cell receptor [4]. The S protein binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is a necessary step for viral entry into the cell. Two currently employed anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines utilize nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA coding for the spike protein. These vaccines activate human immune responses to target the S protein, and about 95% of vaccinated people are protected from severe courses of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [5]. In the case of more contagious variants such as a strain originating from Brazil (known as P.1), the genome has 17 unique mutations, including three in the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein. Mutations in the S protein are thought to be responsible for the variable ability of the spike protein to bind to ACE2, and specifically, the P.1 mutant reveals increased affinity and penetration into the host. Recently, an increasing number of escape mutations in the spike protein threaten the effectiveness of vaccines [6].

In seeking alternative approaches to vaccination, other SARS-CoV-2 proteins can be investigated that control the virus replication. Essential nonstructural proteins are initially expressed as two large polyproteins that are then processed into 16 peptide components. The main protease (Mpro) initially cleaves the polyproteins into 11 fragments. Inhibitors that block the catalytic Mpro activity effectively interrupt the viral replication. One such inhibitor has been recently identified [7]. The crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for the design of improved alpha-ketoamide inhibitors [7] and Mpro appears to be a promising target for designing novel small molecule inhibitors. Since that original study, several promising inhibitor leads have been identified using in silico enzyme modeling [8]. Structure-based computational modeling of ligand–receptor interactions was used by Ibrahim et al. to identify potential Mpro inhibitors [9,10,11,12,13]. Natural products hold a vital role in discovering novel and effective therapeutics to combat the present COVID-19 pandemic. Among natural products, flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoids have attracted great attention as prospective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors [14,15,16]. Recognizing that marine invertebrates are promising organisms for biologically active metabolites including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, antimalarial, antitumor, and antiviral activity [17,18], here biologically active terpene metabolites identified from a coral reef community unique to the Red Sea [19] were screened for in silico binding affinities against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Previously characterized metabolites from this natural-product pool include alismol and aromadendrane sesquiterpenes derived from Litophyton arboretum [20] that exhibit inhibitory activity against the HIV-1 protease (HIV-1 PR) (IC50 7 μM); palustrol, a sesquiterpene from Sarcophyton trocheliophorum that has antibacterial activity (MIC 6.6–11.1 μM) [21]; and 12(S)-Hydroperoxylsarcoph-10-ene, a cembrane diterpene from Sarcophyton glaucum that was reported to exhibit potent anticancer activity via the inhibition of Cyp1A activity (p < 0.01) with IC50 values of 2.7 nM [22]. On the basis of the predicted docking scores, the most potent inhibitors are submitted to molecular dynamics (MD) simulations combined with binding energy calculations using a molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area approach.

2. Results and Discussion

Since the main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 plays an indispensable role in viral reproduction, small molecules were screened based on in silico molecular docking calculations and MD simulations for prospective Mpro inhibitors. Marine natural products identified from the Red Sea provided the source for metabolite screening.

2.1. Molecular Docking

Two hundred and twenty-seven terpene natural products isolated from the biodiverse Red-Sea ecosystem were screened against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) using molecular docking technique. Molecular docking calculations resulted in 27 of the screened compounds exhibiting a higher binding affinity than lopinavir: an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) that was proposed as a treatment for COVID-19 on the basis of in vitro activity, preclinical studies, and observational studies [23]. While docking scores ranged from −4.3 to −12.3 kcal/mol, 12% of the compounds scored below −9.8 kcal/mol (Table S1). AutoDock4.2.6 software was utilized to carry out all molecular docking calculations. Binding affinities, 2D chemical structures, and features of the 27 most promising natural products towards SARS-CoV-2 Mpro are summarized in Table 1. 2D docking positions with proximal amino acid residues within the Mpro active site are depicted in Figure S1. Most of these compounds demonstrate similar Mpro binding modes within the binding pocket, forming hydrogen bonds with CYS145, HIS164, and GLU166, which can account for the high binding affinities (Table 1 and Figure S1). The 2D and 3D representations of the interactions of the top three potent marine natural products (MNPs) and lopinavir with key amino acid residues of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro are depicted in Figure 1 and Figure S2, respectively.

Table 1.

Estimated docking scores, 2D chemical structures, and binding features for lopinavir and the top 27 potent marine natural products (MNPs) towards SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro).

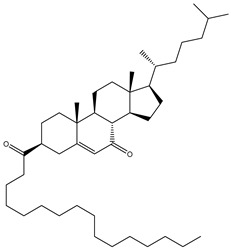

| MNP Name | Plant Source | 2D Chemical Structure | Docking Score (kcal/mol) |

Binding Features a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lopinavir | --- b |

|

−9.8 | HIS164 (2.62 Å), GLY143 (2.01 Å), LEU141 (1.96 Å), SER144 (3.09 Å) |

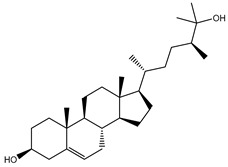

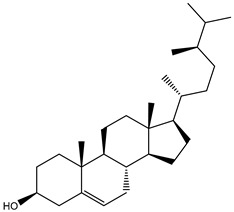

| Depresosterol (190) |

L. depressum |

|

−12.3 | THR26 (2.15, 2.66 Å), HIS41 (2.17 Å), CYS145 (2.70 Å), ASN142 (1.96, 2.04, 2.24 Å), GLU166 (1.99, 2.55 Å) |

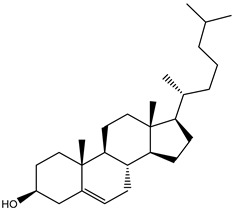

| 3β-25-Dihydroxy-4-methyl-5α,8α-epidioxy-2-ketoergost-9-ene (178) |

Sinularia candidula |

|

−12.2 | LEU141 (2.08 Å), SER144 (1.97, 2.28, 2.66 Å), HIS163 (2.08 Å), CYS145 (2.49 Å), GLN192 (2.26 Å), THR190 (1.80 Å) |

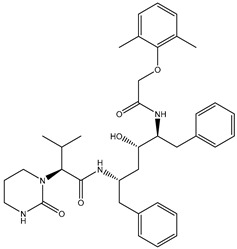

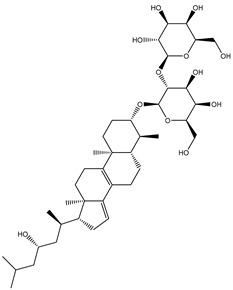

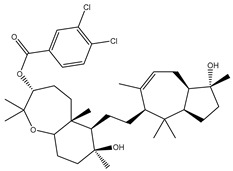

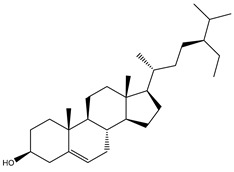

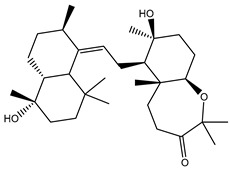

| Erylosides B (226) |

E. lendenfeldi |

|

−12.1 | HIS41 (1.96 Å), TYR54 (3.05 Å), AS142 (1.75, 2.96 Å), GLY143 (2.82 Å), CYS145 (2.04 Å), HIS163 (1.93 Å), GLU166 (2.37 Å), GLN189 (1.91 Å) |

| Sipholenol H (157) |

S. siphonella |

|

−12.0 | GLY143 (1.74 Å), CYS145 (2.88 Å), HIS163 (2.56 Å), HIS164 (2.85 Å), MET165 (2.74 Å), THR190 (1.74, 2.17 Å), GLN192 (2.11 Å) |

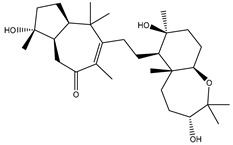

| Dahabinone A (162) |

S. siphonella |

|

−11.9 | CYS145 (2.34 Å), HIS41 (2.43 Å), GLU166 (2.01, 2.23, 2.38 Å), GLY143 (2.12 Å), GLN189 (2.03 Å) |

| Sipholenol I (174) |

S. siphonella |

|

−11.8 | GLY143 (2.04 Å), CYS145 (2.89 Å), HIS163 (2.89 Å), HIS164 (2.01 Å), GLU166 (1.62, 2.03, 2.52 Å) |

| Lobophytosterol (188) |

L. depressum |

|

−11.5 | TYR54 (2.24, 2.55 Å), ASN142 (1.91, 2.75 Å), GLU166 (1.86, 2.66 Å), ASP187 (2.94 Å) |

| (22R,24E,28E)-5β,6β-Epoxy-22,28-oxido-24-methyl-5αcholestan-3β,25,28-triol (191) |

L. depressum |

|

−11.4 | THR26 (2.69 Å), HIS41 (2.14 Å), CYS145 (2.45 Å), ARG188 (2.03 Å), THR190 (2.06, 2.55 Å), GLN192 (2.26 Å) |

| Tasnemoxide A (144) |

D. erythraeanus |

|

−11.4 | CYS44 (2.10 Å), TYR54 (2.54, 2.97 Å), GLU166 (1.91, 1.97 Å) |

| Siphonellinol C (172) |

S. siphonella |

|

−11.3 | GLY143 (1.95 Å), GLN189 (2.09 Å), THR190 (1.73, 2.41 Å), GLN192 (2.10 Å) |

| Siphonellinol-C-23-hydroperoxide (171) |

S. siphonella |

|

−11.2 | GLY143 (2.00 Å), GLN189 (1.97 Å), THR190 (2.03, 2.43 Å), GLN192 (2.46 Å) |

| Erylosides K (224) |

Erylus lendenfeldi |

|

−11.1 | GLU166 (3.03 Å), HIS163 (2.18 Å), HIS164 (2.26, 2.10 Å) |

| Sipholenol D (176) |

S. siphonella |

|

−11.0 | THR190 (2.08 Å), HIS163 (2.48 Å), GLU166 (2.98 Å), GLN189 (1.91 Å) |

| Sipholenone A (175) |

S. siphonella |

|

−11.0 | GLY143 (1.93 Å), HIS163 (2.41 Å), HIS164 (2.54 Å), GLU166 (2.36 Å) |

| Neviotine B (158) |

S. siphonella |

|

−10.9 | ASN142 (2.26 Å), GLU166 (1.95 Å), GLN189 (1.80 Å), THR190 (2.57 Å) |

| Eryloside A (197) |

Genus Erylus |

|

−10.7 | ASN142 (2.32 Å), GLU166 (1.95 Å), THR190 (1.87 Å) |

| Sipholenone D (155) |

S. siphonella |

|

−10.7 | GLN189 (1.77 Å), THR190 (1.83 Å), GLN192 (2.23 Å) |

| 24-Methylcholestane-5-en-3β,25-diol (187) |

S. polydactyla |

|

−10.6 | MET49 (2.16 Å), PHE140 (1.87 Å), GLN189 (2.97 Å) |

| SipholenolA-4-O-3′,4′-dichlorobenzoate (151) |

S. siphonella |

|

−10.5 | HIS163 (2.30 Å), GLN189 (1.78 Å) |

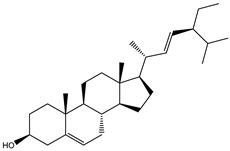

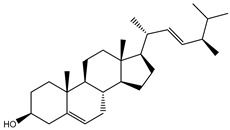

| Stigmasterol (220) |

D. coccinea |

|

−10.5 | MET49 (2.18 Å), GLN189 (2.97 Å) |

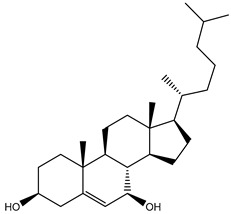

| Cholest-5-en-3β,7β-diol (206) |

A. dichotoma |

|

−10.3 | MET49 (2.17 Å), GLN189 (1.94 Å) |

| Campesterol (221) |

D. coccinea |

|

−10.3 | MET49 (2.17 Å), GLN189 (3.01 Å) |

| Cholesterol (184) |

Dendronephthya |

|

−10.3 | MET49 (2.10 Å), GLN189 (2.97 Å) |

| Clionasterol (219) |

Dragmacidon coccinea |

|

−10.3 | MET49 (2.16 Å), GLN189 (2.95 Å) |

| Brassicasterol (222) |

D. coccinea |

|

−10.1 | MET49 (2.17 Å) |

| 3β-Hexadecanoylcholest-5-en-7-one (202) |

A. dichotoma |

|

−10.0 | GLY143 (1.95 Å) |

| Sipholenone E (163) |

S. siphonella |

|

−9.9 | GLN189 (1.83 Å) |

a Only hydrogen bonds (in Å) were listed. b No plant source was noticed.

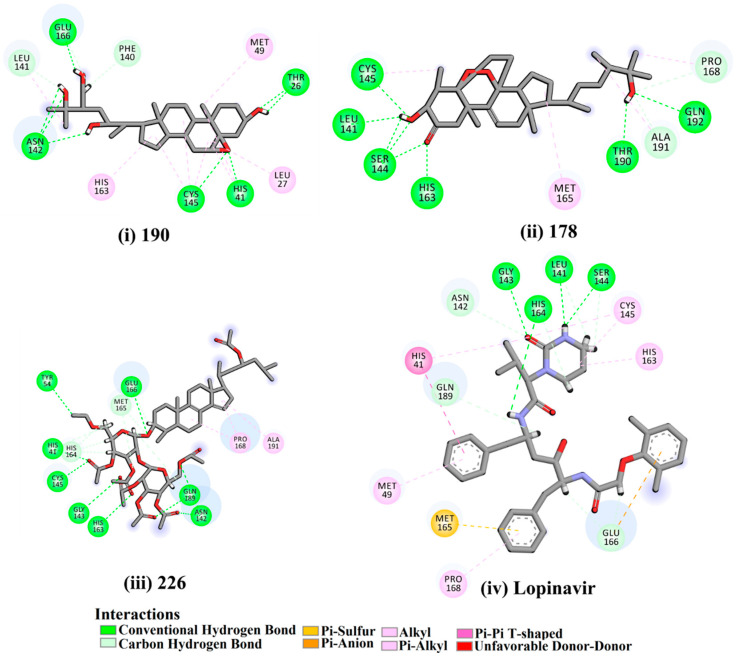

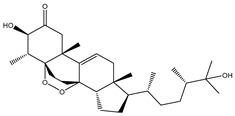

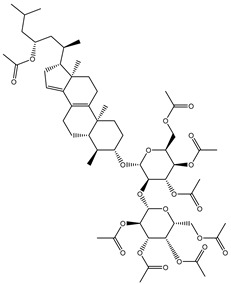

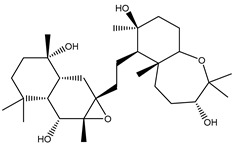

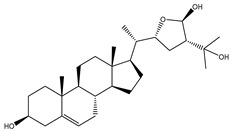

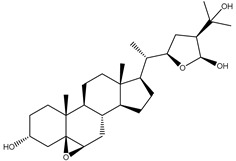

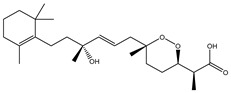

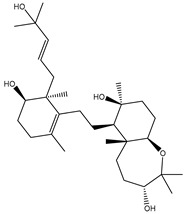

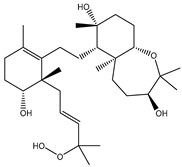

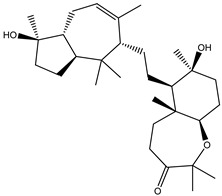

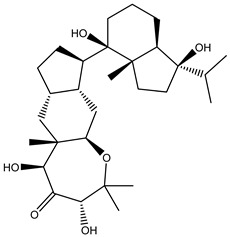

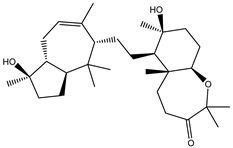

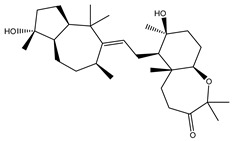

Figure 1.

2D representations of the predicted binding modes of MNPs (i) 190, (ii) 178, (iii) 226, and (iv) lopinavir towards SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro).

Depresosterol (190) isolated from Lobophytum depressum, exhibited the highest binding affinity of the compounds screened against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, with a docking score of −12.3 kcal/mol. in silico Mpro binding in the active site indicated that the methanolic hydroxyl group exhibited two hydrogen bonds with a backbone carboxylate of GLU166 with bond lengths of 1.99 and 2.55 Å, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1). In addition, the hydroxyl unit of 2-methylpropan-2-ol affords three hydrogen bonds with a backbone NH and carbonyl group of ASN142 with bond lengths of 2.24, 2.68, and 2.04 Å, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1). Moreover, the hydroxy group of 2-propanol exhibited a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl group of ASN142 with a bond length of 1.96 Å (Figure 1, Figure S2 and Table 1). The oxygen of the oxirane ring interacted with the backbone imidazole ring of HIS41, and the thiol group of CYS145 with bond lengths of 2.17 and 2.70 Å, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1). The hydroxy group of the cyclohexanol ring contributed two hydrogen bonds with NH and the carbonyl group of TYR26 with bond lengths of 2.15 and 2.66 Å, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1).

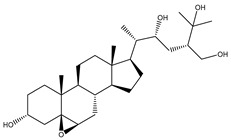

3β-25-Dihydroxy-4-methyl-5α,8α-epidioxy-2-ketoergost-9-ene (178) isolated from Sinularia candidula, exhibited the second highest binding affinity of the compounds screened against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with a docking score of −12.2 kcal/mol. in silico Mpro binding in the active site indicated that the hydroxy group of the hydroxycyclohexanone ring participates in four hydrogen bonds with the backbone carbonyl of LEU141, OH and NH of SER144, and NH of CYS145 with bond lengths of 2.08, 1.97, 2.28, and 2.49 Å, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1). Moreover, the carbonyl group of the hydroxycyclohexanone ring demonstrates two hydrogen bonds with an imidazole ring of HIS163 and backbone OH of SER144 with bond lengths of 2.08 and 2.66 Å, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1). The hydroxy group of 2-methylpropan-2-ol displays two hydrogen bonds with a backbone carbonyl group of THR190 and NH of GLN192 with bond lengths of 1.80 and 2.26 Å, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Erylosides B (226) isolated from Erylus lendenfeldi also exhibited a high binding affinity against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with a docking score of −12.1 kcal/mol. in silico Mpro binding in the active site indicated that the five carbonyl groups of methyl acetates exhibit seven hydrogen bonds with a backbone OH of TYR54, imidazole ring of HIS41, SH of CYS145, imidazole ring of HIS163, NH of ASN142, NH of GLY143, and NH2 of GLN189 with bond lengths of 3.05, 1.96, 2.04, 1.93, 1.75, 2.82, and 1.91 Å, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1). Moreover, the oxygen of the (cyclohexyloxy) cyclohexane ring forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone NH of GLU166 with a bond length of 2.37 Å (Figure 1 and Table 1). The oxygen atom of the methoxy group is also hydrogen bound to the NH of ASN142 with a bond length of 2.96 Å (Figure 1 and Table 1). Compared with 190, 178, and 226, lopinavir presented a similar binding affinity towards Mpro with a docking score of −9.8 kcal/mol. Scrutinizing the binding mode of lopinavir inside the active site of Mpro revealed that the NH of the tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidin-2(1H)-one ring exhibited two hydrogen bonds with a backbone hydroxy group of SER144 and a carbonyl group of LEU141 with bond lengths of 3.09 and 1.96 Å, respectively.

The carbonyl group of the tetrahydro-1-methylpyrimidin-2(1H)-one ring was also observed to form a hydrogen bond with the backbone NH of GLY143 with a bond length of 2.01 Å, and the NH of the methylacetamide group participates in a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl group of HIS164 with a bond length of 2.62 Å (Figure 1 and Table 1). The current results provide quantitative data of the binding affinities of 190, 178, 226, and lopinavir as promising SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors.

2.2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

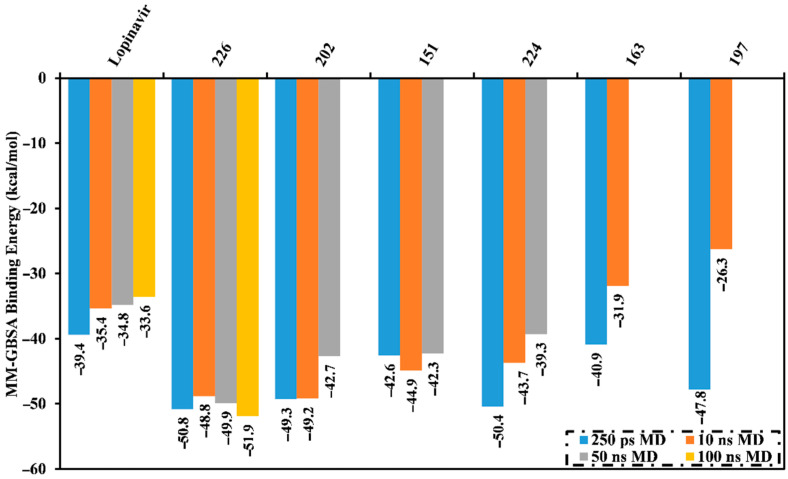

MD simulations probe the stability of the ligand–enzyme complexes, conformational flexibilities, structural details, and the dependability of ligand–enzyme affinities [24,25]. Therefore, those natural products with low Mpro docking scores were submitted for MD simulations followed by binding energy calculations. The simulations were conducted with an implicit water solvent for 250 ps, and the molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) approach was applied to estimate the corresponding binding affinities; thereby diminishing the time and computational costs (see computational methodology section for details). The calculated MM/GBSA binding energies for the pre-screened natural products are summarized in Table S2. Six compounds had lower binding energies (ΔGbinding) than lopinavir (calc. −39.4 kcal/mol). These metabolites were further subjected to a 10 ns MD simulation in an explicit water solvent to obtain more accurate Mpro binding affinities. MD/MM/GBSA binding energies were estimated (Figure 2). Four of these compounds exhibited lower binding energies (ΔGbinding) compared to lopinavir (calc. −35.4 kcal/mol). Moreover, those potent MNPs were chosen and submitted for 50 ns MD simulations in the explicit water solvent, and the corresponding binding energies were evaluated (Figure 2). Only erylosides B (226) exhibited steady binding throughout the simulation, while 202, 151, and 224 showed an increase in MM/GBSA binding energies over the simulated time. For instance, the calculated MM/GBSA binding energies for 226 against Mpro were −50.8, −48.8 and −50.0 kcal/mol over 250 ps implicit-solvent MD, 10 ns explicit-solvent MD, and 50 ns explicit-solvent MD simulations, respectively. This shows the importance of long MD simulations to predict metabolite-Mpro binding affinities. Therefore, MD simulations for the 226-Mpro complex were prolonged to 100 ns, and the corresponding MM/GBSA binding energy was calculated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) binding energies for lopinavir and the top natural products complexed with Mpro over 250 ns in an implicit water solvent, and 10 ns, 50 ns, and 100 ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in an explicit water solvent.

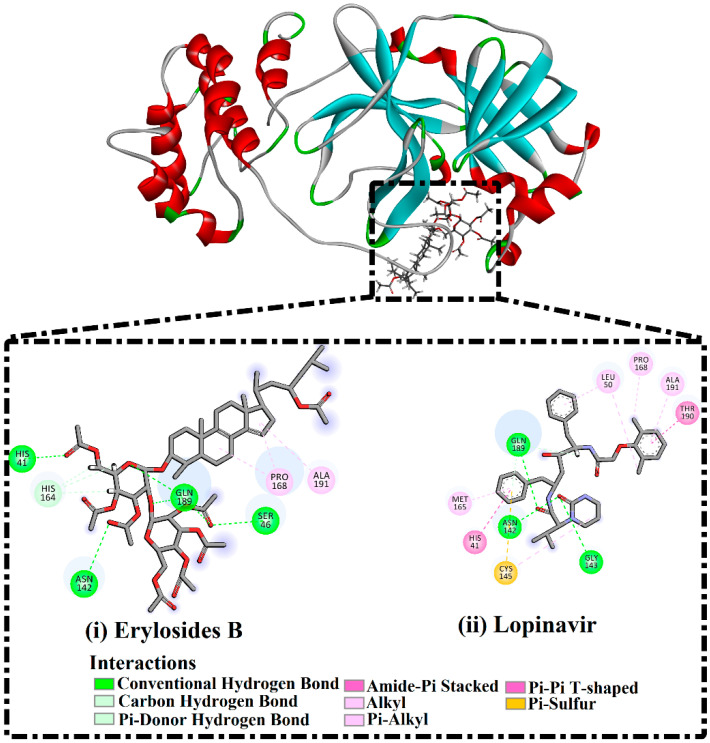

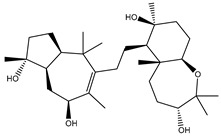

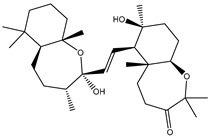

No appreciable variance between the calculated MM/GBSA binding energy for the 226-Mpro complex throughout the 50 ns MD simulation and the corresponding MM/GBSA binding energy throughout the 100 ns MD simulation were observed (Figure 2). Compared with lopinavir, 226 showed a higher binding affinity towards Mpro over the 100 ns MD simulation with an average ΔGbinding of −51.9 kcal/mol. Hydrogen bonding, pi-based, hydrophobic, and van der Waals interactions with essential amino acid residues within the Mpro active site are all thought to contribute to the strong binding constant. The 2D and 3D representations for 226 and lopinavir within the Mpro active site over 100 ns are shown in Figure 3 and S3, respectively. Interestingly, 226 maintained hydrogen bonding with the proximal amino acid residues of Mpro over the 100 ns MD course (Figure 3). Structural insights into the binding mode of the 226 with the Mpro demonstrated that the carbonyl groups of methyl acetates form four hydrogen bonds with the backbone imidazole of the HIS41, OH of SER146, the carbonyl group of ASN142, and NH2 of GLN189, with bond lengths of 2.72, 2.76, 3.37, and 1.89 Å, respectively (Figure 3); while the oxygen of the (cyclohexyloxy) cyclohexane ring forms hydrogen bonds with the backbone NH2 of GLN189 with a bond length of 2.62 Å (Figure 3). Furthermore, the oxygen of tetrahydro-2H-pyran bonds with the backbone NH2 of GLN189 with a bond length of 2.06 Å (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

2D representations of binding modes of (i) erylosides B (226)- and (ii) lopinavir-Mpro complexes according to an average structure over a 100 ns MD simulation.

While lopinavir also displayed high Mpro binding energy over the 100 ns MD simulation at ΔGbinding −33.6 kcal/mol, only three hydrogen bonds were observed with the proximal amino acid residues of Mpro (Figure 3). A comparison of the erylosides B (226) and lopinavir revealed that the binding affinity of erylosides B (226) was approximately two times higher than that of lopinavir.

The estimated MM/GBSA binding energies were further decomposed into separate components to indicate the force in the binding of Mpro with erylosides B (226) and lopinavir (Table 2). Evdw was a significant contributor to the erylosides B (226)- and lopinavir-Mpro binding affinities with average values of −71.2 and −45.6 kcal/mol, respectively. Eele was efficient with an average value of −30.5 and −22.1 kcal/mol for the erylosides B (226)- and lopinavir-Mpro binding affinities, respectively.

Table 2.

Components of the MM/GBSA binding energies for erylosides B (226)- and lopinavir-Mpro complexes as determined by MD simulation at 100 ns.

| Compound Name | Calculated MM/GBSA Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆EVDW a | ∆Eele b | ∆EGB c | ∆ESUR d | ∆Ggas e | ∆GSolv f | ∆Gbinding g | |

| Erylosides B (226) | −71.2 | −30.5 | 58.1 | −8.3 | −101.7 | 49.8 | −51.9 |

| Lopinavir | −45.6 | −22.1 | 39.9 | −5.7 | −67.8 | 34.2 | −33.6 |

a van der Waals energy. b electrostatic energy. c The electrostatic solvation free energy calculated from the generalized Born equation. d The nonpolar component of the solvation energy. e Total gas phase energy. f The solvation free energy. g The evaluated free energy calculated from the terms above.

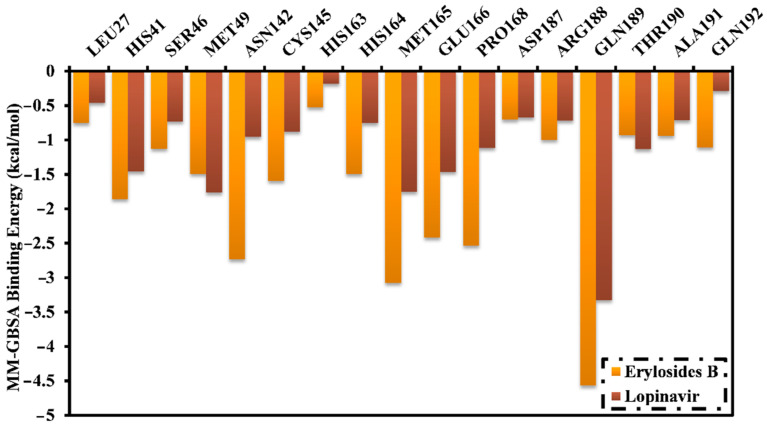

The binding energies of erylosides B (226)- and lopinavir-Mpro complexes were further decomposed at the per-residue level and the residues with absolute energy contribution < −0.50 kcal/mol were shown (Figure 4). MET165, GLU166, PRO168, and GLN189 in the Mpro complex favorably participate with erylosides B (226) and lopinavir. There was a considerable contribution by GLN189 to the total binding free energy with values of −4.6 and −3.3 kcal/mol for erylosides B (226) and lopinavir, respectively. Additionally, the hydrophobic residues share greater energies as a result of the formation of the hydrophobic interactions between erylosides B (226) and hydrophobic residues.

Figure 4.

Energy contributions (kcal/mol) for Mpro amino acid residues to the binding free energy of erylosides B (226) and lopinavir.

2.3. Post-Dynamics Analyses

To further confirmed the stability and behavior of erylosides B (226) complexed with Mpro, structural and energetic analyses were executed during 100 ns MD simulations and compared to those of lopinavir. Control of the structural stability of the studied system was accomplished by investigating root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), center-of-mass (CoM) distance, hydrogen bond length, and binding energy per frame.

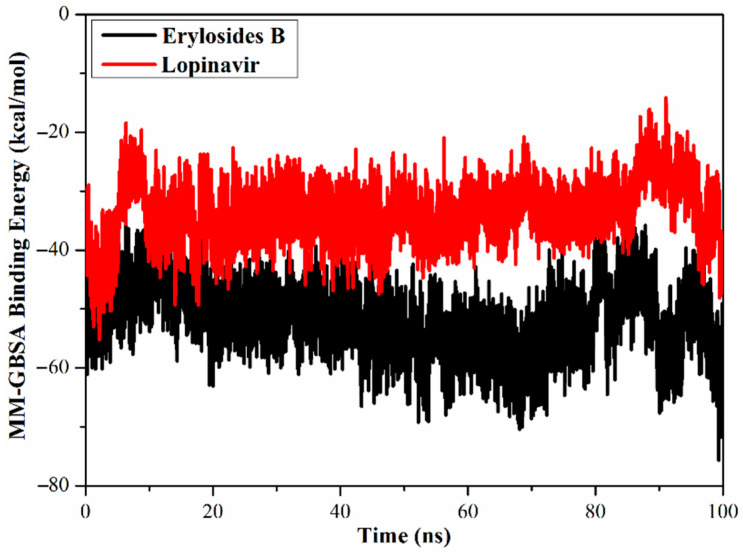

2.3.1. Binding Energy per Frame

The global structural stability of erylosides B (226) and lopinavir in complex with Mpro was estimated over the 100 ns MD simulations by measuring the correlation between the binding energy per frame and time (Figure 5). Overall stabilities for erylosides B (226) and lopinavir exhibited average binding energies (ΔGbinding) of −51.9 and −33.6 kcal/mol, respectively. According to this analysis, all complexes conserved stability throughout the 100 ns MD simulation.

Figure 5.

Calculated MM/GBSA binding energy per frame for erylosides B (black) and lopinavir (red) with Mpro over 100 ns MD simulations.

2.3.2. Hydrogen Bond Length

Hydrogen bond analyses for erylosides B (226)- and lopinavir-Mpro complexes over a 100 ns MD simulation were performed (Table 3). Four hydrogen bonds with GLN189, GLU166, CYS145, and ASN142 were observed within the erylosides B (226)-Mpro complex. Average bond lengths were 2.9, 2.8, 2.9, and 2.7 Å, with occupation percentages of 96, 92, 91, and 83%, respectively. In contrast, two hydrogen bonds were detected for the lopinavir-Mpro complex, with GLN189 and GLY143 showing an average bond length of 2.8 and 2.7 Å and an occupation percentage of 85.6 and 75.6%, respectively. Overall, these hydrogen bond analyses supported the finding of high stability for the erylosides B (226)-Mpro complex compared to lopinavir-Mpro.

Table 3.

Distance, occupancy, and hydrogen bonding for erylosides B (226) and lopinavir with key Mpro amino acid residues.

| Compound Name | Acceptor | Donor | Distance (Å) a | Angle (degree) a | Occupied (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erylosides B (226) |

GLN_189@O | Erylosides B @O5-H29 | 2.9 | 142 | 95.7 |

| GLU166@O | Erylosides B @O3-H16 | 2.8 | 141 | 92.3 | |

| CYS145@O | Erylosides B @O12-H44 | 2.9 | 152 | 91.1 | |

| ASN142@O | Erylosides B @O16-H29 | 2.7 | 156 | 83.3 | |

| Lopinavir | GLN189@O | Lopinavir @O9-H19 | 2.8 | 145 | 85.6 |

| GLY143@O | Lopinavir @O12-H28 | 2.7 | 158 | 75.6 |

a The hydrogen bonds are inspected by the acceptor-H-donor angle of >120° and acceptor-donor atom distance < 3.5 Å. b Occupancy is employed to estimate the strength and stability of the hydrogen bond.

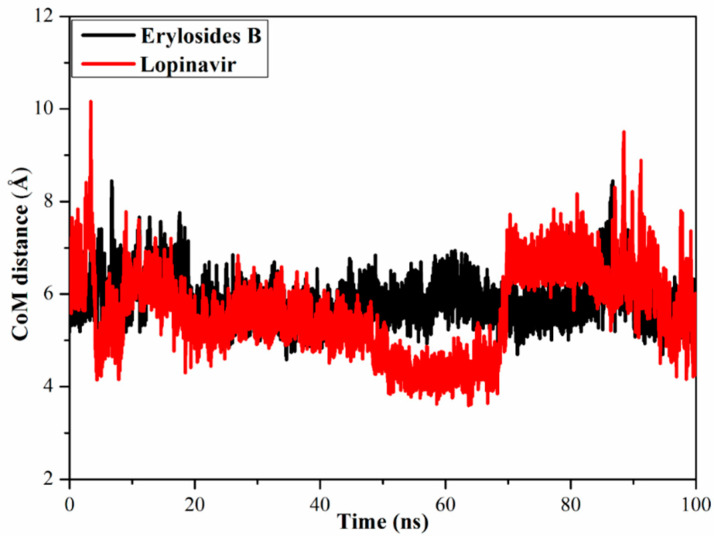

2.3.3. Center-of-Mass Distance

To gain a more in-depth insight into the stability of ligand-Mpro during the MD simulation, center-of-mass (CoM) distances were measured (Figure 6). Interestingly, CoM distances were consistent for the erylosides B (226)-Mpro complex compared to lopinavir-Mpro, with average values of 5.6 vs. 5.9 Å, respectively. This suggests that erylosides B (226) bound more tightly to the Mpro complex than lopinavir.

Figure 6.

Center-of-mass (CoM) distances (in Å) between erylosides B (black) and lopinavir (red) and GLN189 of Mpro over a 100 ns MD simulation.

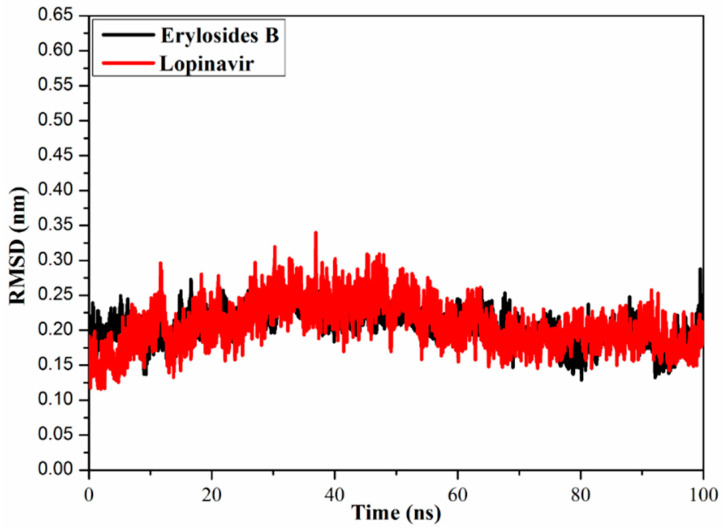

2.3.4. Root-Mean-Square Deviation

To watch the structural stability of the erylosides B (226)- and lopinavir-Mpro complexes, the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values of the backbone atoms of the whole complex were estimated (Figure 7). Unambiguously, the estimated RMSD values for the investigated complexes remained below 0.20 nm over the 100 ns MD simulations. The erylosides B (226)- and lopinavir-Mpro complexes reached the steady state in the first 10 ns MDs, and continued in an almost stationary state until the end of the simulations. The current results emphasized that the erylosides B (226) is tightly bonded and does not impact the overall topology of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Figure 7.

Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the backbone atoms from the initial structure of erylosides B (black) and lopinavir (red) with Mpro throughout a 100 ns MD simulation.

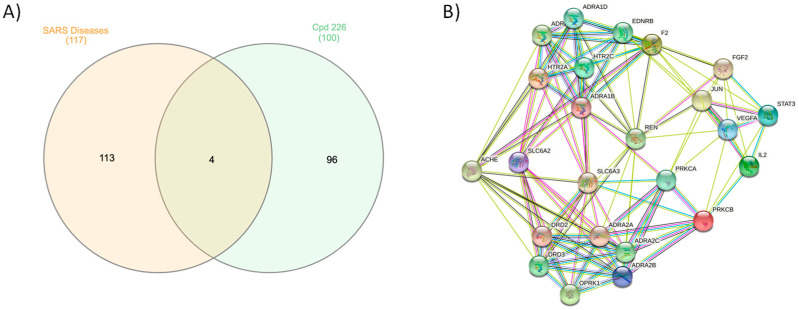

2.4. Molecular Target Prediction and Network Analysis

Erylosides B (226) protein targets associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome diseases were predicted using a SwissTargetPrediction DisGeNET online tool. One hundred and seventeen genes were identified using Venn diagram comparison analysis. Commonly shared genes for erylosides B (226) were BCL2L1, IL2, PRKCA, and PRKCB (Figure 8). Several studies reported that these four genes alter cytokine levels and immune functions in patients with COVID-19 infections and related conditions [26,27]. Erylosides B (226) predicted gene targets were also analyzed via a STRING protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and visualized by Cytoscape 3.8.0. The top 20 scored genes for erylosides B (226) also included BCL2L1, IL2, PRKCA, and PRKCB (Table S3).

Figure 8.

(A) Venn diagram analysis for erylosides B (226) with SARS disease genes and (B) STRING PPI network for the top targets identified by network analyzer for erylosides B (226) as a Mpro inhibitor.

2.5. Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA)

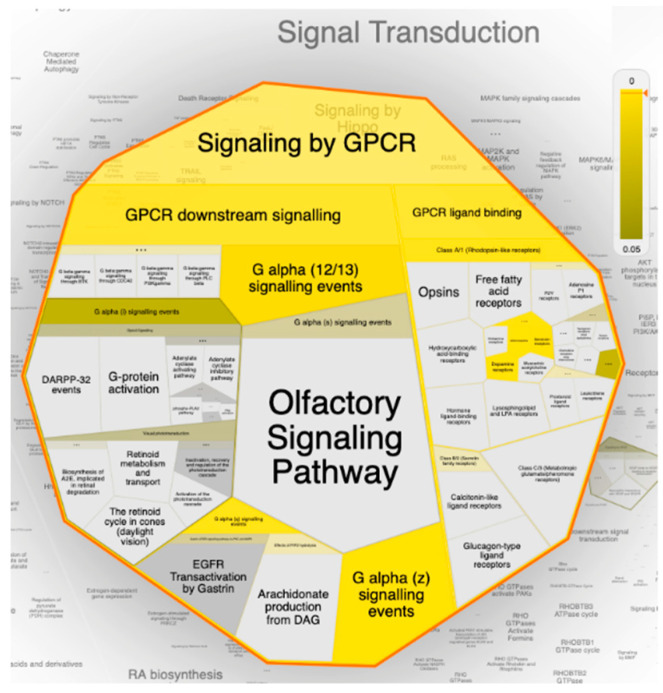

Toward a deep dissection and mining of the erylosides B (226) target–function interactions, PEA analysis and Boolean network modeling were conducted. A Voronoi treemap of erylosides B (226) top targeted pathway affected by the top 20 gene targets in response to erylosides B (226) in terms of SARS-CoV-2 infection was constructed (Figure 9). Moreover, a Reactome hierarchy map was built to provide a genome-wide representation of the pathways influenced in response to erylosides B treatment (Figure S4). Remarkably, among the top 20 enriched pathways from the Reactome–PEA analyses and signal transduction, immune system and homeostasis signaling pathways were found to be the major pathways targeted by erylosides B (226), with a high significance (FDR < 0.00001%) (Table S4).

Figure 9.

The Voronoi treemap of the top pathway (signal transduction) influenced by the top 20 gene targets in response to erylosides B (226) in term of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The color highlights the over-representation of that pathway in the input dataset. Light grey signifies pathways that are not significantly over-represented.

Interestingly, under signal transduction, it was found that the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling pathway was the most enriched pathway influenced by erylosides B (226) treatment within the human genome. Mining of the Reactome–PEA analysis results emphasized that a set of 15 genes (OPRK1, HTR2C, PRKCA, HTR2A, ADRA1D, PRKCB, DRD2, DRD3, ADRA2A, EDNRB, ADRA1A, ADRA2B, ADRA1B, ADRA2C, and F2) were significantly modulated as biological targets to erylosides B (226) as potent SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor. Additionally, the Reactome–PEA results revealed that these genes were found to interact with other genes/interactors, including P16220, P52292, P00533, P12931, P07550, P35414, P01019, P30559, P14416, and O15354.

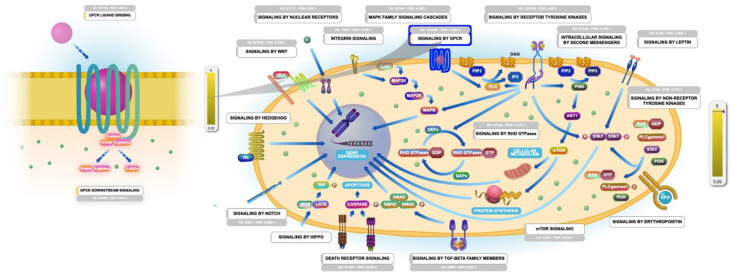

GPCRs are a massive family of surface transmembrane receptors in a human cell capable of responding to numerous stimulants and promoting a cascade of cellular functions. According to the GPCRs’ pharmacological attributes, they are divided into four prominent families: the rhodopsin-like receptors family, the secretin receptors family, the metabotropic glutamate/pheromone receptors family, and the frizzled receptors family [28]. Remarkably, the Reactome–PEA analyses results revealed that almost all GPCR prominent families were significantly influenced by erylosides B (Figure 10). Many recent studies found that SARS-CoV-2 may compromise the GPCR signaling pathway and contribute to pulmonary edema’s pathophysiology [29]. Additionally, recent reports speculated that SARS-CoV-2 might hijack the GPCR signaling pathway— mimicking a previous case report in cholera toxin, ADP-ribosylation Gαs—to activate CFTR and switch on Cl- secretion, eventually leading to dysregulation of lung ion and fluids transmission, which ultimately led to lung edema in COVID-19 patients [30].

Figure 10.

Graphic representation of the Reactome pathways influenced as a response to erylosides B (226) in term of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The representation showing the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling pathway as the most enriched pathway influenced by erylosides B (226) treatment in the human genome.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Mpro Preparation

The resolved three-dimensional (3D) structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) with a resolution of 2.16 Å (PDB code: 6LU7 [31]) complexed with peptidomimetic inhibitor (N3) was downloaded and used as a template for all molecular docking and MD calculations. The protein structure was prepared by removing all heteroatoms, crystallographic waters, and ions, conserving only the amino acid residues. The protonation states of amino acid residues of Mpro were assigned using H++ web server, and all missing hydrogen atoms were inserted [32]. The pKa values of Mpro amino acid residues were estimated under physical conditions of salinity = 0.15, internal dielectric constant = 10, pH = 7, and external dielectric constant = 80.

3.2. Inhibitor Preparation

The chemical structures of the 227 scrutinized marine natural products (MNPs) described in literature as Red-Sea terpenes were obtained in SDF format from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). All MNPs were processed using Omega2 software to generate the three-dimensional (3D) structures of the studied molecules [33,34]. Merck Molecular Force Field 94 (MMFF94S), implemented inside SZYBKI software [35,36], was applied to minimize the geometry of the investigated MNPs. The two-dimensional (2D) chemical structures of the scrutinized molecules are presented in Table S1.

3.3. Molecular Docking

All molecular docking calculations were executed using AutoDock4.2.6 software [37]. The pdbqt file of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) was prepared on the basis of the AutoDock protocol [38]. The maximum number of energy evaluations (eval) and the genetic-algorithm number (GA) were adjusted to 25,000,000 and 250, respectively. All other docking parameters were conserved at default. The grid box dimensions were adjusted to 60 Å × 60 Å × 60 Å to cover the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro binding pocket. Moreover, the grid spacing value was set to 0.375 Å. The coordinates of the grid center were located at −13.069, 9.740, and 68.490 in the x, y, and z directions, respectively. The atomic partial charges of the investigated MNPs were calculated using the Gasteiger method [39]. The predicted binding poses for each investigated MNP were processed by the built-in clustering analysis (1.0 Å RMSD tolerance), and the conformation with the lowest energy within the most massive cluster was picked out as a representative pose.

3.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

AMBER16 software was employed to perform all MD simulations for the most potent MNPs complexed with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [40]. Mpro and the investigated MNPs were determined using AMBER force field 14SB [41] and General AMBER force field (GAFF2) [42], respectively. In the present study, implicit-solvent and explicit-solvent MD simulations were performed. In the implicit-solvent MD simulations, the atomic partial charges of the investigated MNPs were evaluated using the AM1-BCC method [43]. No periodic boundary conditions and no cut-off were applied for nonbonded interactions (specifically, a cutoff value of 999 Å was employed). Furthermore, the solvent influence was estimated using igb = 1 solvent model [44]. Energy minimization was first carried out on the docked MNP-Mpro complexes for 500 steps, and the minimized complexes were then gently heated from 0 K to 300 K over 10 ps under NVT condition using a Langevin thermostat. Finally, the production stage was executed over 250 ps, and snapshots were assembled every 1 ps, giving 250 snapshots. In the present study, all implicit-solvent MD simulations were conducted using the CPU version of pmemd (pmemd.MPI) implemented inside AMBER16.

In explicit-solvent MD simulations, the atomic partial charges of the investigated MNPs were estimated using the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) approach at the HF/6-31G* level with the help of Gaussian09 software [45,46]. The TIP3P water model with periodic boundary conditions was utilized to solvate the MNP-Mpro complexes in a cubic water box with a minimum distance to the box edge of 15 Å. Energy minimizations for 5000 steps on the solvated MNP-Mpro complexes were performed using combined steepest and conjugate gradient methods. The minimized complexes were then smoothly heated from 0 to 300 K over 50 ps and a restraint of 10 kcal mol−1 Å−1 was applied on the main protease. The complexes were then equilibrated under NPT conditions for 1 ns. The production stage was then performed for each investigated Mpro-inhibitor complex over simulation times of 10 ns, 50 ns, and 100 ns. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method was applied to estimate the long-range electrostatic forces and energies. Cut-off for coulombic interactions with a value of 12 Å was considered [47]. To maintain the temperature at 298 K, Langevin dynamics with a gamma_ln collision frequency set to 1.0 was utilized. A Berendsen barostat with a pressure relaxation time of 2 ps was applied for the pressure control [48]. To constrain all bonds including hydrogen atoms, a SHAKE algorithm with a time step of 2 fs was utilized [49]. For binding energy calculations and post-dynamics analyses, energy values and coordinates were collected every 10 ps over the production stage. All explicit-solvent MD simulations were executed utilizing the GPU version of pmemd (pmemd.cuda) implemented inside AMBER16. All in silico calculations involving quantum mechanics, molecular docking calculations, and MD simulations were carried out on the CompChem GPU/CPU cluster (hpc.compchem.net). BIOVIA DS Visualize 2020 was utilized to generate all molecular graphics [50].

3.5. Free Binding Energy Calculations

The molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) approach [51] was applied to evaluate the binding free energies of the most potent MNPs complexed with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. To appoint the polar solvation energy, the modified GB model proposed by Onufriev [52] (igb = 2) was employed. The uncorrelated snapshots collected throughout the MD simulations were subjected to MM/GBSA (ΔGbinding) energy calculations, which estimated as follows:

| ΔGbinding = GComplex − (GMNP + GMpro) | (1) |

where the energy term (G) is evaluated as:

| G = Eele + Evdw + GSA + GGB | (2) |

Eele and Evdw and are electrostatic and van der Waals energies, respectively. GSA is the nonpolar contribution to the solvation-free energy from the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA). GGB is the electrostatic solvation free energy calculated from the generalized Born equation. A single-trajectory approach was applied, in which the coordinates of each MNP-Mpro, Mpro, and MNP were acquired from a single trajectory. Because of the expensive computational request and low prediction thoroughness in most cases, entropy calculations were ignored [53,54].

3.6. Protein–Protein Interaction and Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA)

According to the structural resemblance of recognized inhibitor–target integrations, target forecasting of the most auspicious marine natural products was carried out utilizing the online web-based tools of SwissTargetPredicition (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch). Moreover, the DisGeNET online database (https://www.disgenet.org) was applied to gather the accessible database for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) diseases. The InteractiVenn online tool was employed to design Venn diagram [55]. A functional database of STRING for top predicted targets was applied to generate protein–protein interaction (PPI) network [56]. Cytoscape 3.8.2 was applied to examine target-function relation according to the network topological [57]. Furthermore, to explore all probable target–function relations for the top 20 SARS disease-related genes based on their network profiles, pathway enrichment analysis was achieved using Cytoscape 3.8.2 [57]. Lastly, the ReactomeFIViz tool was integrated for modeling and visualizing all potential drug–target interactions [58].

4. Conclusions

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is apparent that zoonotic diseases pose a huge risk to public health and economic stability. A lack of targeted treatments has spurred the exploration of novel drug leads for which computational approaches provide a relatively quick and cost-effective approach. Herein, marine natural products isolated from the Red Sea were screened in silico as potential Mpro inhibitors. On the basis of molecular docking calculations, MD simulations, and molecular mechanics/generalized born surface area binding energy calculations, erylosides B (226) demonstrated a favorable binding affinity with ΔGbinding < −51.0 kcal/mol with Mpro. The stability of 226 complexed with Mpro was confirmed using energetic and structural analyses over the 100 ns MD simulation. Ultimately, we hypothesize that the utilization of erylosides B may represent a potential therapeutic approach against COVID-19 due to its useful capability to modulate the GPCR signaling pathway in COVID-19 patients. Experimental validation is expected to further identify the suitability of natural products such as erylosides B to serve as a SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online. Figure S1: 2D representations of interactions of lopinavir and the top 27 potent marine natural products (MNPs) with the proximal amino acid residues of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro), Figure S2: 3D representations of predicted binding modes of (i) 190, (ii) 178, (iii) 226 and (iv) lopinavir towards SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro), Figure S3: 3D representations of binding modes of (i) erylosides B (226)- and (ii) lopinavir-Mpro complexes according to an average structure over a 100 ns MD simulation, Figure S4: a genome-wide Reactome hierarchy map of the pathways influenced by the top 20 gene targets in response to erylosides B (226) in term of SARS-CoV-2 infection, Table S1: evaluated docking score (in kcal/mol) for lopinavir and all investigated marine natural products (MNPs) against SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro), Table S2: computed Autodock and MM/GBSA binding energies (in kcal/mol) for the top 27 potent marine natural products (MNPs) against SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) over 250 ps implicit solvent MD simulations, Table S3: network topological analysis for the predicted targets for erylosides B (226), Table S4: top 20 most relevant pathways for erylosides B (226) targets resulted from Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A.I. and M.-E.F.H.; Data curation, A.H.M.A. and K.A.A.A.; Formal analysis, A.H.M.A. and M.A.M.A.; Investigation, A.H.M.A. and M.-E.F.H.; Methodology, M.A.A.I.; Project administration, M.A.A.I. and M.-E.F.H.; Resources, M.A.A.I.; Software, M.A.A.I.; Supervision, M.A.A.I.; Visualization, A.H.M.A. and M.A.M.A.; Writing—original draft, A.H.M.A., K.A.A.A. and T.A.M.; Writing—review & editing, M.A.A.I., M.A.M.A., M.A.M.A.-H., E.M.E., M.F.M., F.A., K.S.A., H.R.E.-S., P.W.P., T.E. and M.-E.F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Mahmoud F. Moustafa extends his appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work under grant No. (R.G.P.1/143/42). H. R. El-Seedi is very grateful supported by the Swedish Research Council Vetenskapsrådet (VR-05885) and the Department of Molecular Biosciences, Wenner-Grens Institute, Stockholm University, Sweden, for the financial support. The computational work was completed with resources supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund, STDF, Egypt, Grants No. 5480 & 7972 (Granted to M.A.A.I). Mohamed Hegazy gratefully acknowledges the financial support from Alexander von Humboldt Foundation “Georg Foster Research Fellowship for Experienced Researchers”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

The samples are not available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Vicenzi E., Canducci F., Pinna D., Mancini N., Carletti S., Lazzarin A., Bordignon C., Poli G., Clementi M. Coronaviridae and SARS-associated coronavirus strain HSR1. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:413–418. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.030683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng Q., Peng R., Yuan B., Zhao J., Wang M., Wang X., Wang Q., Sun Y., Fan Z., Qi J., et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of the nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 core polymerase complex from SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107774–107788. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harapan H., Itoh N., Yufika A., Winardi W., Keam S., Te H., Megawati D., Hayati Z., Wagner A.L., Mudatsir M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020;13:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang Y., Yang C., Xu X.F., Xu W., Liu S.W. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2020;41:1141–1149. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai L., Gao G.F. Viral targets for vaccines against COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021;21:73–82. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00480-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemp S.A., Collier D.A., Datir R.P., Ferreira I., Gayed S., Jahun A., Hosmillo M., Rees-Spear C., Mlcochova P., Lumb I.U., et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03291-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved alpha-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar Y., Singh H., Patel C.N. In silico prediction of potential inhibitors for the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 using molecular docking and dynamics simulation based drug-repurposing. J. Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1210–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim M.A.A., Abdelrahman A.H.M., Allemailem K.S., Almatroudi A., Moustafa M.F., Hegazy M.-E.F. In silico evaluation of prospective anti-COVID-19 drug candidates as potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Protein J. 2021:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10930-020-09945-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim M.A.A., Abdelrahman A.H.M., Hussien T.A., Badr E.A.A., Mohamed T.A., El-Seedi H.R., Pare P.W., Efferth T., Hegazy M.F. In silico drug discovery of major metabolites from spices as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020;126:104046–104055. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim M.A.A., Abdelrahman A.H.M., Hegazy M.F. In-silico drug repurposing and molecular dynamics puzzled out potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1791958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibrahim M.A.A., Abdeljawaad K.A.A., Abdelrahman A.H.M., Hegazy M.F. Natural-like products as potential SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors: In-silico drug discovery. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1790037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibrahim M.A.A., Mohamed E.A.R., Abdelrahman A.H.M., Allemailem K.S., Moustafa M.F., Shawky A.M., Mahzari A., Hakami A.R., Abdeljawaad K.A.A., Atia M.A.M. Rutin and flavone analogs as prospective SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: In silico drug discovery study. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2021:107904. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2021.107904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zakaryan H., Arabyan E., Oo A., Zandi K. Flavonoids: Promising natural compounds against viral infections. Arch. Virol. 2017;162:2539–2551. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3417-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherrak S.A., Merzouk H., Mokhtari-Soulimane N. Potential bioactive glycosylated flavonoids as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: A molecular docking and simulation studies. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0240653–e0240666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jo S., Kim S., Kim D.Y., Kim M.-S., Shin D.H. Flavonoids with inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020;35:1539–1544. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2020.1801672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer A.M., Rodriguez A.D., Berlinck R.G., Hamann M.T. Marine pharmacology in 2003–4: Marine compounds with anthelmintic antibacterial, anticoagulant, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antiplatelet, antiprotozoal, antituberculosis, and antiviral activities; affecting the cardiovascular, immune and nervous systems, and other miscellaneous mechanisms of action. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharm. 2007;145:553–581. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer A.M., Hamann M.T. Marine pharmacology in 2000: Marine compounds with antibacterial, anticoagulant, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antiplatelet, antituberculosis, and antiviral activities; affecting the cardiovascular, immune, and nervous systems and other miscellaneous mechanisms of action. Mar. Biotechnol. 2004;6:37–52. doi: 10.1007/s10126-003-0007-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegazy M.E., Mohamed T.A., Alhammady M.A., Shaheen A.M., Reda E.H., Elshamy A.I., Aziz M., Pare P.W. Molecular architecture and biomedical leads of terpenes from red sea marine invertebrates. Mar. Drugs. 2015;13:3154–3181. doi: 10.3390/md13053154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koop K., Booth D., Broadbent A., Brodie J., Bucher D., Capone D., Coll J., Dennison W., Erdmann M., Harrison P., et al. ENCORE: The effect of nutrient enrichment on coral reefs. Synthesis of results and conclusions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2001;42:91–120. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(00)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayyad S.N., Alarif W.M., Al-Footy K.O., Selim E.A., Ghandourah M.A., Aly M.M., Alorfi H.S. Isolation, antimicrobial and antitumor activities of a new polyhydroxysteroid and a new diterpenoid from the soft coral Xenia umbellata. Z Nat. C J. Biosci. 2017;72:27–34. doi: 10.1515/znc-2015-0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegazy M.E., Gamal Eldeen A.M., Shahat A.A., Abdel-Latif F.F., Mohamed T.A., Whittlesey B.R., Pare P.W. Bioactive hydroperoxyl cembranoids from the Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton glaucum. Mar. Drugs. 2012;10:209–222. doi: 10.3390/md10010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horby P.W., Mafham M., Bell J.L., Linsell L., Staplin N., Emberson J., Palfreeman A., Raw J., Elmahi E., Prudon B., et al. Lopinavir–ritonavir in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1345–1352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Vivo M., Masetti M., Bottegoni G., Cavalli A. Role of molecular dynamics and related methods in drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:4035–4061. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerrigan J.E. Molecular dynamics simulations in drug design. In: Kortagere S., editor. In Silico Models for Drug Discovery. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ, USA: 2013. pp. 95–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noroozi R., Branicki W., Pyrc K., Labaj P.P., Pospiech E., Taheri M., Ghafouri-Fard S. Altered cytokine levels and immune responses in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and related conditions. Cytokine. 2020;133:155143–155147. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y., Hou Y., Shen J., Huang Y., Martin W., Cheng F. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2020;6:14. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oldham W.M., Hamm H.E. Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:60–71. doi: 10.1038/nrm2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birch C.A., Molinar-Inglis O., Trejo J. Subcellular hot spots of GPCR signaling promote vascular inflammation. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2021;16:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.coemr.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hameid R.A., Cormet-Boyaka E., Kuebler W.M., Uddin M., Berdiev B.K. SARS-CoV-2 may hijack GPCR signaling pathways to dysregulate lung ion and fluid transport. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2021;320:L430–L435. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00499.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., et al. Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon J.C., Myers J.B., Folta T., Shoja V., Heath L.S., Onufriev A. H++: A server for estimating pKas and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W368–W371. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkins P.C., Skillman A.G., Warren G.L., Ellingson B.A., Stahl M.T. Conformer generation with OMEGA: Algorithm and validation using high quality structures from the Protein Databank and Cambridge Structural Database. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010;50:572–584. doi: 10.1021/ci100031x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.OMEGA 2.5.1.4. OpenEye Scientific Software; Santa Fe, NM, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.SZYBKI 1.9.0.3. OpenEye Scientific Software; Santa Fe, NM, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halgren T.A. MMFF VI. MMFF94s option for energy minimization studies. J. Comput. Chem. 1999;20:720–729. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199905)20:7<720::AID-JCC7>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forli S., Huey R., Pique M.E., Sanner M.F., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. Computational protein-ligand docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11:905–919. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gasteiger J., Marsili M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electronegativity—A rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:3219–3228. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(80)80168-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Case D.A., Betz R.M., Cerutti D.S., Cheatham T.E., Darden T.A., Duke R.E., Giese T.J., Gohlke H., Goetz A.W., Homeyer N., et al. AMBER 2016. University of California; San Francisco, CA, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maier J.A., Martinez C., Kasavajhala K., Wickstrom L., Hauser K.E., Simmerling C. ff14SB: Improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J., Wolf R.M., Caldwell J.W., Kollman P.A., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jakalian A., Jack D.B., Bayly C.I. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:1623–1641. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roux B., Simonson T. Implicit solvent models. Biophys Chem. 1999;78:1–20. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4622(98)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bayly C.I., Cieplak P., Cornell W.D., Kollman P.A. A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges—The RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. doi: 10.1021/j100142a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., et al. Gaussian 09. Gaussian Inc.; Wallingford, CT, USA: 2009. Revision E01. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: AnN⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. doi: 10.1063/1.464397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., Vangunsteren W.F., Dinola A., Haak J.R. Molecular-dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. doi: 10.1063/1.448118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyamoto S., Kollman P.A. Settle—An Analytical Version of the Shake and Rattle Algorithm for Rigid Water Models. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:952–962. doi: 10.1002/jcc.540130805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, B.D.S.V., Version 2019. Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA; San Diego, CA, USA: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Massova I., Kollman P.A. Combined molecular mechanical and continuum solvent approach (MM-PBSA/GBSA) to predict ligand binding. Perspect Drug Discov. Des. 2000;18:113–135. doi: 10.1023/A:1008763014207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Onufriev A., Bashford D., Case D.A. Exploring protein native states and large-scale conformational changes with a modified generalized born model. Proteins. 2004;55:383–394. doi: 10.1002/prot.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hou T., Wang J., Li Y., Wang W. Assessing the performance of the molecular mechanics/Poisson Boltzmann surface area and molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area methods. II. The accuracy of ranking poses generated from docking. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:866–877. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang E., Sun H., Wang J., Wang Z., Liu H., Zhang J.Z.H., Hou T. End-Point Binding Free Energy Calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: Strategies and Applications in Drug Design. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:9478–9508. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heberle H., Meirelles G.V., da Silva F.R., Telles G.P., Minghim R. InteractiVenn: A web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinform. 2015;16:169–175. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li R., Ma X., Song Y., Zhang Y., Xiong W., Li L., Zhou L. Anti-colorectal cancer targets of resveratrol and biological molecular mechanism: Analyses of network pharmacology, human and experimental data. J. Cell Biochem. 2019;120:11265–11273. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blucher A.S., McWeeney S.K., Stein L., Wu G. Visualization of drug target interactions in the contexts of pathways and networks with ReactomeFIViz. F1000Research. 2019;8:908. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.19592.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.