Abstract

Expanded polystyrene (EPS), which is difficult to decompose, is usually buried or incinerated, causing the natural environment to be contaminated with microplastics and environmental hormones. Digestion of EPS by mealworms has been identified as a possible biological solution to the problem of pollution, but the complete degradation mechanism of EPS is not yet known. Intestinal microorganisms play a significant role in the degradation of EPS by mealworms, and relatively few other EPS degradation microorganisms are currently known. This study observed significant differences in the intestinal microbiota of mealworms according to the dietary results of metagenomics analysis and biodiversity indices. We have proposed two new candidates of EPS-degrading bacteria, Cronobacter sakazakii and Lactococcus garvieae, which increased significantly in the EPS feeding group population. The population change and the new two bacteria will help us understand the biological mechanism of EPS degradation and develop practical EPS degradation methods.

Keywords: Cronobacter sakazakii, Expanded polystyrene, Intestinal, Lactococcus garvieae, Mealworm, Metagenomics

Introduction

Expanded polystyrene (EPS) is mainly used for disposable or short-term products owing to its light weight and low price. Polystyrene ([−CH(C6H5)CH2 −]n) is known to be very difficult to biodegrade due to its high molecular weight, hydrophobicity, and strong structural stability [1, 2]. Therefore, most EPS waste is currently disposed of in landfill or by incineration [3]. The degradation of EPS requires ultraviolet (UV) light and oxygen [4]. Therefore, burying EPS will block UV light and oxygen and will make it more stable, so that decomposition takes even longer. Incineration requires a large amount of energy and creates toxic substances, such as dioxin [2]. Because of this degradation stability, most of the EPS waste is dispersed in nature, such as in the soil, rivers, lakes, and seas, creating microplastics [5, 6]. It has been reported that microbial decomposition of styrene, a monomer of polystyrene, is converted to phenylacetyl-CoA through four enzymatic reactions, and then decomposed by entering the TCA cycle [7].

Microbial biodegradation of petroleum compounds causing environmental pollution is being studied in an environmentally friendly way [8]. One new solution to the EPS problem is the mealworm’s ability to break down plastics. Mealworms (yellow mealworm) are the larvae of Tenebrio molitor, which can be found all over the world, including Korea [9]. The life cycle of T. molitor has four stages – egg, larva, chrysalis, and adult – resulting in a complete transformation. They are widely used as biological research models because they are easy to handle and to breed using oats, wheat bran grain with potato, cabbage, carrots, and apples [10, 11]. In addition, mealworms have a high protein content and are excellent as a food [12].

Since the mechanisms of chemical and physical changes in the biodegradation and mineralization of polystyrene by mealworms were identified [10], mealworms have become a new solution to the EPS problem. In addition to mealworms, Zophobas morio larvae (superworms) and Tenebrio obscurus larvae (dark mealworms) are also able to degrade EPS [13, 14]. The most researched subject in EPS biodegradation is the mealworm owing to its ease of breeding and shorter metamorphic periods compared with other insects [13]. A survey of 22 countries, including Korea, found that mealworms in all regions consume EPS and that chewing and digesting EPS are considered universal characteristics of mealworms [9]. The microorganisms in the mealworm gut play a significant role in EPS degradation [15]. Indeed, EPS biodegradation may be due to the application of enteric microorganisms. It has been suggested that enteric microorganisms release extracellular oxidative enzymes that assist EPS degradation [9], but the exact mechanism is unknown. The first EPS-degrading microorganism was Exiguobacterium sp. YT2 [15], and then others were identified, including Rhodococcus ruber [9]. According to a previous study [15], gentamicin inhibited the growth of Exiguobacterium sp. YT2 and eventually reduced the EPS degradation of the mealworms. However, another study suggested the possibility of the presence of other EPS-degrading bacteria based on the greater inhibition of EPS degradation by citopcin than gentamicin [16]. There are a wide variety of bacterial species in the intestine of mealworms, and the intestinal microbial flora change according to its diet [17]. Currently, there are a few types of EPS-degrading microorganisms, and there are still more that are unknown. The discovery of more EPS-degrading microorganisms and their biological mechanisms will reveal the biological mechanism of EPS degradation. In this study, we observed changes in the intestinal microbiota according to the EPS diet of the mealworms.

Materials and Methods

Mealworms and Chemicals

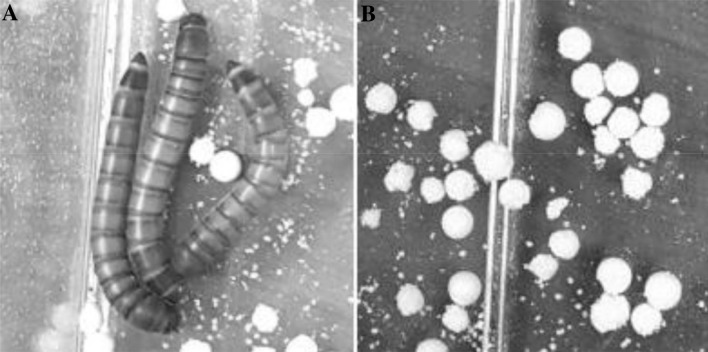

Mealworms (T. molitor larvae) in Fig. 1a were purchased from ‘nb Mealworm Insect Farm’ (Yangju, Korea). Mealworms were bred in 8 L boxes made of polypropylene and were fed with either bran or EPS for the experiment. Bran was also purchased from ‘nb Mealworm Insect Farm’, and EPS was provided by Woosung Resin Co., Ltd. (Gimhae, Korea). EPS is a spherical (bead) plastic containing an effervescent gas, which was produced as a bead from the styrene monomer of Lotte Chemical Co. (Seoul, Korea). The polystyrene was foamed approximately 55 times. Beads consisted of 93%–96% EPS (CAS number: 9003–53-6), 4%–7% pentane (CAS number: 109–66-0), and less than 1% 1,2,5,6,9,10-hexabromocyclododecane (CAS number: 3194–55-6), with a diameter of 0.4–1.7 mm.

Fig. 1.

Mealworms and their diet of EPS. a Mealworms used in this study. b Beads of EPS after 2 weeks. The irregular sphere shape indicates that EPS was ingested by the mealworms

The bran and EPS were treated prior to feeding. The bran was sterilized at 121°C for 10 min in an autoclave then dried in an oven at 80°C for 10 min and cooled at room temperature. The EPS was sterilized for 10 min at 80°C and then cooled at room temperature. Saline solution (0.85%, w/v) was prepared by mixing 17 g of NaCl with 2 L of distilled water and sterilized for 20 min at 121°C using an autoclave.

Breeding Mealworms

After receiving the mealworms, they were fed with bran for 4 days for stabilization and separated from the bran and feces. The separated mealworms were divided into four groups, two groups for bran feeding and two for EPS feeding. The groups had similar total weights: 22.0 ± 0.5 g. All groups were fed at room temperature on a controlled diet for 2 weeks. The breeding boxes were kept closed to maintain humidity and to prevent contamination and were covered with boxes to create a dark environment. The lid was opened twice a day to ventilate the boxes for 5 min. In order to minimize the intake of non-feeding substances, carcasses, shells, and pupa were removed twice daily.

Extracting the Digestive Tract of Mealworms

Mealworms were separated from the EPS and bran, and each group was weighed for comparison. A three-stage pretreatment was performed before the digestive tract was extracted. The mealworms were immersed in 75% ethanol for 1 min and washed twice with saline solution. The head and the tail of the pretreated mealworms were each grasped using tweezers and carefully pulled apart to separate the mealworm’s digestive tract. The separated digestive tract with around 1 g for each sample was immediately deposited into a tube and stored in a freezer at −80 °C until analysis. The extracted digestive tract was not washed, and only those without damage were used for further analysis.

Microbial Flora Analysis by Metagenomics

Intestinal microbial analysis of the extracted digestive tract was conducted by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Korea). The order number was HN00116441. The all collected frozen extracted digestive tract of mealworms was send to Macrogen Inc. without any further treatment. The 16S rRNA gene library of the intestinal microorganisms was prepared using Herculase II Fusion DNA Polymerase Nextera XT Index Kit V2 according to 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Part #15,044,223 Rev. B. The nucleotide sequences of the prepared library were analyzed by next-generation sequencing using Illumina platform. A MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 was used for the sequencing process. The raw sequence data were assembled with FLASH (1.2.11) [18], pre-processed and clustered with CD-HIT-OUT [19], assigned taxonomical positions with QIIME-UCLUST program and RDP-16S rRNA database. The statistically analysis for alpha- and beta-diversity were calculated with QIIME [20] or according formulas described by Przemieniecki et al. [21]. Random taxa with the density of less than 0.1% were not included in the analysis.

Results and Discussion

Changes in the Weight of Mealworms by Diet

Previous studies have already demonstrated that mealworms ingest and degrade EPS and that intestinal microorganisms play an important role in this degradation [10, 15]. The irregular shape of the spherical EPS suggests that mealworms ingest EPS (Fig. 1b). After a controlled diet for 2 weeks, the bran-fed group increased in weight by 15.20%, but the EPS-fed group decreased in weight by 13.52%. This observation is consistent with those of previous studies [10, 22–24]. EPS provides barely enough energy for mealworms to survive.

Changes to Microbial Flora in the Digestive Track by Diet

From the 16S rRNA sequences analysis of mealworm intestinal microorganisms for a metagenomics analysis, the read counts were 32,211 and 30,952 for the bran-fed group and 37,771 and 42,807 for the EPS-fed group. The composition of the microbial flora at the taxonomic stage is presented in Table 1. The intestinal microbial flora composition of the bran-fed group was significantly different from that of the EPS-fed group. The intestinal microbial flora of mealworms depend on food [25]. It was shown that the food ingested by mealworms was mostly discharged from the middle and rear intestines after up to 2 days [26]. Before the experiment, all the mealworms were reared on the same farm and fed the same bran in the same breeding box for 4 days before being randomly divided into two groups. Therefore, it was expected that the intestinal microbial flora would be similar between the two groups. The difference in intestinal microbial flora between the bran-fed and EPS-fed group was mainly dietary. Fifteen species of intestinal bacteria were identified in the bran-fed group, but only seven species of bacteria were identified in the EPS-fed group (Table 1). The reduced microbial diversity of the EPS-fed group might be due to the chemical simplicity of EPS.

Table 1.

Population changes in the intestinal microbial flora by diet. Identified strains with a population density of less than 0.1% in both the bran-fed group and the EPS-fed group are not presented in this table

| Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Species | Population density (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The bran-fed group | The EPS-fed group | |||||

| Firmicutes | Bacilli | Bacillales | Bacillaceae | Bacillus alkalinitrilicus | 9.13 | 0.00 |

| Lactobacillales | Bacillus velezensis | 0.96 | 0.00 | |||

| Enterococcaceae | Enterococcus hirae | 5.94 | 4.08 | |||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus crispatus | 1.09 | 0.00 | |||

| Lactobacillus graminis | 6.44 | 3.04 | ||||

| Lactobacillus johnsonii | 0.11 | 0.00 | ||||

| Lactobacillus salivarius | 1.38 | 0.00 | ||||

| Pediococcus pentosaceus | 10.16 | 0.48 | ||||

| Streptococcaceae | Lactococcus garvieae | 4.82 | 36.86 | |||

| Lactococcus taiwanensis | 2.40 | 0.41 | ||||

| Clostridia | Clostridiales | Clostridiaceae | Clostridium oryzae | 5.28 | 0.00 | |

| Peptostreptococcaceae | Clostridioides difficile | 0.25 | 0.00 | |||

| Ruminococcaceae | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | 0.20 | 0.00 | |||

| Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria | Enterobacterales | Enterobacteriaceae | Cronobacter sakazakii | 0.77 | 25.47 |

| Tenericutes | Mollicutes | Entomoplasmatales | Spiroplasmataceae | Spiroplasma velocicrescens | 50.53 | 29.66 |

Biodiversity indexes (Table 2) showed a high difference level between bran and EPS diets. The average population density was similar in both variant (~ 6.6). The Sørensen–Dice coefficient reached 64%. The shannon index for the bran-fed group was 1.691, while for the EPS-fed group it was 0.731. The domination index was 1.4 times higher for the bran-fed group compared to the EPS-fed group. The average population density of bacterial community in both variants was similar, however other indices were significantly different. The diversity of the bacterial community in the EPS variant was as much as 2.3 times lower than in the community observed in the bran-fed group. This indicates a severe reduction in the number of taxa in the EPS diet, as evidenced directly by the Sørensen-Dice index indicating the disappearance of almost half of the taxa compared to the bran-based diet. Nevertheless, three species of bacteria were dominant in the EPS-based diet, with Spiroplasma velocicrescens still remained the dominant taxa in both diets. This indicates that Spiroplasma spp. is necessary for the proper functioning of the digestive system of insects. The appearance of Lactococcus garvieae and Cronobacter sakazaki show their possible contribution to EPS degradation [11, 17, 27, 28].

Table 2.

The biodiversity indices of bacterial community

| Indices | The bran-fed group | The EPS-fed group |

|---|---|---|

| Average population density | 6.631 | 6.667 |

| Number of taxa | 15 | 7 |

| Sørensen–Dice coefficient | 0.636 | |

| Dominance index | 0.696 | 0.497 |

| Diversity index | 1.691 | 0.731 |

By evaluating the strains with significant differences in diet, it was possible to suggest the microorganisms involved in EPS degradation. Spiroplasma velocicrescens represented 50.53% of the microorganisms in the bran-fed group, but this decreased to 29.66% in the EPS-fed group. Pediococcus pentosaceus represented 10.16% of the bran-fed group but only 0.48% of the EPS-fed group. Bacillus alkalinitrilicus represented 9.13% of the bran-fed group but was not detected in the EPS-fed group. The population density of these three strains was significantly reduced by EPS feeding, suggesting that they are unlikely to be involved in EPS degradation.

The population density of Cronobacter sakazakii, belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family, was increased by 24.70% in the EPS-fed group. Similar changes in the Enterobacteriaceae family following EPS feeding were observed in previous studies [13], and microbes, suggested to be Aeromonas sp. and Klebsiella pneumoniae by 16S rRNA analysis, are known to grow on polystyrene [14], even though they were not identified in this study. All these results suggest that the Enterobacteriaceae family is highly involved in EPS degradation. EPS degradation by C. sakazakii has not been observed; however, considering that C. sakazakii can grow on abiotic surfaces, such as stainless steel or polyester plastic [29], the results of this study indicate that this microorganism may be involved in the degradation of EPS.

The population density of the Streptococcaceae family was 30.05% higher in the EPS-fed group than in the bran-fed group. This observation was in contrast to a previous study [13]. The presence of the Lactococcus genus in the intestine of mealworms has been reported in several previous studies [27, 28]. However, previous studies have shown that the population density of the Lactococcus genus was very low, regardless of diet [17], or less when feeding with EPS than with bran [9]. Therefore, based on the results of this study, it was proposed that Lactococcus garvieae may be involved in EPS degradation. Although it is not known whether they live in the intestine of mealworms, L. lactis, L. curvatus, L. brevis, and L. reuteri form a biofilm on the surface of polystyrene [30], and L. lactis subsp. cremoris (strain SK11) has a KEGG pathway associated with styrene degradation (BioModels Database Identifier: BMID000000076767 [31]). L. taiwanensis and L. garvieae were also identified in this study. However, the EPS diet caused very opposite effects on the two strains. The difference that showed the opposite of the change in distribution by the EPS feeding at the species level suggests that the EPS degrading ability is different at the species level of the microorganism or at a lower taxonomic rank.

Microorganisms that exist independently in nature must be prepared for various environmental stresses. However, microorganisms that coexist within the host depend on the homeostasis provided by the host and perform host-specific metabolism [32, 33]. Polystyrene intake by mealworms will contribute to the enrichment of intestinal symbiotic microbes involved in the degradation of polystyrene. This is an excellent model for biodegradation of polystyrene in nature, and provides an optimal place to find related microorganisms. In this study, a list of microorganisms involved in the degradation of expanded polystyrene is proposed by presenting the intestinal microbiota of mealworms that ingested expended polystyrene using a metagenomic analysis. This will be the fundamental data for confirming the ability to degrade polystyrene by the symbiotic microorganisms from the mealworm, and conducting researches on the its biological mechanism in the future.

Authors' information

JB, HC, HJ, JP, SY, SH, and YL are students in Department of Forest Products and Biotechnology, College of Science and Technology, Kookmin University, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, 02,707, Republic of Korea. T-JK is a professor at the same department.

Acknowledgements

The fund for this study including metagenomics analysis was supported by department expenditures for experimentation practical training from Kookmin University. This study was carried out with the support of ´R&D Program for Forest Science Technology (Project No. 2019150B10-2123-0301)´ provided by Korea Forest Service(Korea Forestry Promotion Institute).

Author contributions

JB, HC, HJ, JP, SY, SH, and YL suggested the concept of study, designed and conducted the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the experimental data, and wrote the manuscript as a team. T-JK suggested the concept of study, decided the experimental conditions, analyzed and interpreted the experimental data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The fund for this study including metagenomics analysis was supported by department expenditures for experimentation practical training from Kookmin University. This study was carried out with the support of ´R&D Program for Forest Science Technology (Project No. 2019150B10-2123–0301)´ provided by Korea Forest Service(Korea Forestry Promotion Institute).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gautam R, Bassi AS, Yanful EK. A review of biodegradation of synthetic plastic and foams. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2007;141:85–108. doi: 10.1007/s12010-007-9212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pushpadass HA, Weber RW, Dumais JJ, Hanna MA. Biodegradation characteristics of starch-polystyrene loose-fill foams in a composting medium. Bioresource Technol. 2010;101:7258–7264. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faravelli T, Pinciroli M, Pisano F, Bozzano G, Dente M, Ranzi E. Thermal degradation of polystyrene. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2001;60:103–121. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2370(00)00159-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yousif E, Haddad R. Photodegradation and photostabilization of polymers, especially polystyrene: review. Springerplus. 2013;2:398–398. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hidalgo-Ruz V, Gutow L, Thompson RC, Thiel M. Microplastics in the marine environment: A review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:3060–3075. doi: 10.1021/es2031505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu W-M, Yang J, Criddle CS. Microplastics pollution and reduction strategies. Front Env Sci Eng. 2016;11:6. doi: 10.1007/s11783-017-0897-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mooney A, Ward PG, O’Connor KE. Microbial degradation of styrene: biochemistry, molecular genetics, and perspectives for biotechnological applications. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2006;72:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varjani S, Upasani VN. Comparing bioremediation approaches for agricultural soil affected with petroleum crude: A case study. Indian J Microbiol. 2019;59:356–364. doi: 10.1007/s12088-019-00814-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang S-S, Wu W-M, Brandon AM, Fan H-Q, Receveur JP, Li Y, Wang Z-Y, Fan R, McClellan RL, Gao S-H, Ning D, Phillips DH, Peng B-Y, Wang H, Cai S-Y, Li P, Cai W-W, Ding L-Y, Yang J, Zheng M, Ren J, Zhang Y-L, Gao J, Xing D, Ren N-Q, Waymouth RM, Zhou J, Tao H-C, Picard CJ, Benbow ME, Criddle CS. Ubiquity of polystyrene digestion and biodegradation within yellow mealworms, larvae of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Chemosphere. 2018;212:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y, Yang J, Wu W-M, Zhao J, Song Y, Gao L, Yang R, Jiang L. Biodegradation and mineralization of polystyrene by plastic-eating mealworms: Part 1. Chemical and physical characterization and isotopic tests. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:12080–12086. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung J, Heo A, Park YW, Kim YJ, Koh H, Park W. Gut microbiota of Tenebrio molitor and their response to environmental change. J Microbiol Biotechn. 2014;24:888–897. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1405.05016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaly AE, Alkoaik F. The yellow mealworm as a novel source of protein. Am J Agr Biol Sci. 2009;4:319–331. doi: 10.3844/ajabssp.2009.319.331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng B-Y, Su Y, Chen Z, Chen J, Zhou X, Benbow ME, Criddle CS, Wu W-M, Zhang Y. Biodegradation of polystyrene by dark (Tenebrio obscurus) and yellow (Tenebrio molitor) mealworms (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53:5256–5265. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhi-Long T, Ting-An K, Hsiao-Han L. The study of the microbes degraded polystyrene. Adv Technol Inno. 2017;2:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Yang J, Wu W-M, Zhao J, Song Y, Gao L, Yang R, Jiang L. Biodegradation and mineralization of polystyrene by plastic-eating mealworms: Part 2. Role of gut microorganisms. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:12087–12093. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H-A, Kim H-Y, Choi H-J Study on the plastic degrading bacteria in insect larvae. In . International Meeting of the Microbiological Society of Korea. Korea: Gwangju; 2016. p. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandon AM, Gao S-H, Tian R, Ning D, Yang S-S, Zhou J, Wu W-M, Criddle CS. Biodegradation of polyethylene and plastic mixtures in mealworms (Larvae of Tenebrio molitor) and effects on the gut microbiome. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:6526–6533. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Fu L, Niu B, Wu S, Wooley J. Ultrafast clustering algorithms for metagenomic sequence analysis. Brief Bioinform. 2012;13:656–668. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Przemieniecki SW, Damszel M, Kurowski TP, Mastalerz J, Kotlarz K. Identification, ecological evaluation and phylogenetic analysis of non-symbiotic endophytic fungi colonizing timothy grass and perennial ryegrass grown in adjacent plots. Grass Forage Sci. 2019;74:42–52. doi: 10.1111/gfs.12404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Q, Tao H, Wong MH. Feeding and metabolism effects of three common microplastics on Tenebrio molitor L. Environ Geochem Hlth. 2019;41:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s10653-018-0161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen G-Z, Bai-Lu Z, Meng-Meng J, Xiao-Gang W, Jun-Yi Z, Jia-Nan C, Yun W, Hao T, Xiao-Jun Z. Gut microbiota of polystyrene-eating mealworms analyzed by high-throughput sequencing. Microbiol China. 2017;44:2011–2018. doi: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.170301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bożek M, Hanus-Lorenz B, Rybak J. The studies on waste biodegradation by Tenebrio molitor. E3S Web Conf. 2017;17:00011. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/20171700011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genta FA, Dillon RJ, Terra WR, Ferreira C. Potential role for gut microbiota in cell wall digestion and glucoside detoxification in Tenebrio molitor larvae. J Insect Physiol. 2006;52:593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung M, Kwon E-Y, Hwang J-S, Goo T-W, Yun E-Y (2013) Pre-treatment conditions on the powder of Tenebrio molitor for using as a novel food ingredient. J Sericultural Entomol Sci 51 10.7852/jses.2013.51.1.9

- 27.Nukmal N, Umar S, Amanda SP, Kanedi M. Effect of styrofoam waste feeds on the growth, development and fecundity of mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) Online J Biol Sci. 2018;18:24–28. doi: 10.3844/ojbsci.2018.24.28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Przemieniecki SW, Kosewska A, Ciesielski S, Kosewska O. Changes in the gut microbiome and enzymatic profile of Tenebrio molitor larvae biodegrading cellulose, polyethylene and polystyrene waste. Environ Pollut. 2020;256:113265. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henry M, Fouladkhah A. Outbreak history, biofilm formation, and preventive measures for control of Cronobacter sakazakii in infant formula and infant care settings. Microorganisms. 2019;7:77. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7030077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schirone M, Visciano P, Tofalo R, Suzzi G. Editorial: Biological hazards in food. Front Microbiol. 2017;7:2154. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chelliah V, Juty N, Ajmera I, Ali R, Dumousseau M, Glont M, Hucka M, Jalowicki G, Keating S, Knight-Schrijver V, Lloret-Villas A, Natarajan KN, Pettit J-B, Rodriguez N, Schubert M, Wimalaratne SM, Zhao Y, Hermjakob H, Novère NL, Laibe C. BioModels: ten-year anniversary. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D542–D548. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang G, Zhang S, Li Z, Huang J, Liu Y, Liu Y, Wang Q, Li X, Yan Y, Li M. Comparison between the gut microbiota in different gastrointestinal segments of large-tailed han and small-tailed han sheep breeds with high-throughput sequencing. Indian J Microbiol. 2020;60:436–450. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00885-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan M, Zhang X, Hu L, Huang X, Zhou Q, Zeng G, Zhang J, Xiao G, Chai X, Chen J. Bacterial community dynamics during nursery rearing of pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) revealed via high-throughput sequencing. Indian J Microbiol. 2020;60:214–221. doi: 10.1007/s12088-019-00853-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]