Abstract

Despite recent improvement in implant survival rates, there remains a significant demand for enhancing the long-term clinical efficacy of titanium (Ti) implants, particularly for the prevention of peri-implantitis. Bioactive substances such as antimicrobial peptides are emerging as effective alternatives for contemporary antimicrobial agents used in dental health care. Current research work was focused to use laterosporulins that are non-haemolytic cationic antimicrobial peptides from Brevibacillus spp. for coating commercially available Ti discs. The coated Ti surfaces were evaluated in vitro for biofilm formation by two dental plaque isolates Streptococcus gordonii strain DIGK25 and S. mutans strain DIGK119 as representatives of commensal and pathogenic streptococci respectively. The biofilm inhibition was ascertained with replicated experiments on hydroxyapatite discs and confirmed by florescence microscopy. The laterosporulin coated Ti discs showed significantly reduced biofilm formation by oral streptococci and displayed promising potential to enhance the antibacterial surface properties. Such improvised Ti surfaces may curb the menace of oral streptococcal biofilm formation on dental implants and the associated implant failures.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptides, Titanium, Dental implants, Biofilm, Oral microflora

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, the use of dental implants has exponentially risen, promoting research and development of novel materials and techniques based on collective clinical experience and higher expectations of patients [1]. Although implants are a routine procedure with good predictability and survival rates [2], yet a number of complications are of concern for long term function. With the significant rise of implants placed, it is observed that the number of implant failure are also consistently rising [3]. Most of the studies identified the bacterial infections of implant surrounding soft tissues as a primary factor contributing towards inflammatory disease around the implants i.e., peri-implantitis and implant failures [4]. Typical failure mechanisms include tissue damage and implant detachment due to bacterial biofilm. Presence of biofilms of oral pathogenic organisms are a well-documented cause of periimplant infections. High degree of antibiotic tolerance in microbes residing in biofilms have made it imperative to identify novel agents, targeted to prevent the biofilm formation on the surface of dental implants [5]. A number of treatment approaches including chemical plaque control agents, decontaminants for implant surfaces, non-surgical therapy as well as surgical techniques have been utilized, though with limited efficacy in the management of periimplantitis. So far, no universally accepted modality has emerged to prevent or control such infections.

Antimicrobial Peptides (AMP) is a novel class of compounds, which have become a recent focus of interest. These peptides are often small in size (20–60 amino acid residues), cationic and amphipathic in nature [6]. The mechanism of antimicrobial activity is often correlated with permeabilization of the target-cell membrane, however, other mechanisms have also been proposed [6]. Some of the short peptides particularly from Gram positive microorganisms act as quorum sensing inhibitors and assist quorum quenching to disrupt microbial biofilms [7, 8]. Prokaryotic AMPs are generally termed as bacteriocins that exhibit specific and narrow spectrum of action with a high potency. These characteristics of efficient and selective killing activity against other microorganisms make these AMPs as promising biotherapeutic agents for antimicrobial therapy for diverse human infectious diseases [9]. Titanium (Ti) and its alloys are most widely used materials in the development of dental implants owing to their properties such as excellent corrosion resistance, as well as the stimulation of bone cell growth [10, 11]. Modifications such as surface etching with basic and acidic solutions or coatings with bioactive materials have been shown to increase the bioactivity of Ti and Ti alloy surface [12]. Methods to reduce the biofilm formation on the surface of implants is a novel field of interest and diverse methods of surface modifications of Ti to enhance the antimicrobial characteristics have been explored in the recent past [12]. The current investigation aims at the screening of previously characterized bacteriocins viz., laterosporulins that displayed human β-defensin like structure [13, 14] for effectiveness against oral streptococcal biofilms and to develop bacteriocin coated Ti discs for potential dental applications like implant surfaces with improvised antibacterial properties.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Ti discs (commercially pure Ti, medical grade, 1inch × 0.02 (diameter × thickness) in ASTM-B-265/ASME-SB-265 GR-2 specifications) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (USA). The surface of the discs was then wet-polished with silicon carbide abrasive papers in an increasing order of grit i.e. 400, 800 and 1200 resp. The discs were further cleaned by ultrasonic bathing in distilled water, acetone, 75% ethanol and distilled water. Hydroxyapatite (HA) discs (Dense Ceramic Hydroxyapatite discs, 9.5 mm dia. × 2 mm Thickness) were obtained from Clarkson Chromatography Products (Williamsport, PA, USA) and sterilized by autoclaving while Ti discs were exposed to ultraviolet radiation overnight and autoclaved.

Isolation and Identification of Bacterial Isolates

Bacterial strains were isolated from subgingival plaque samples of healthy individuals and patients suffering from periodontitis as described earlier [15]. Samples were diluted and plated on media plates including brain heart infusion agar (BHI, Himedia, India), de man Rogosa and Sharpe agar (MRS, Himedia, India), reinforced clostridial agar (RCA, Himedia, India) and tryptone soya agar (TSA, Himedia, India). All isolated colonies were restreaked and upon checking the purity they were preserved as − 70 °C glycerol stocks for further studies. The molecular identification was performed by PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene using universal primers as mentioned earlier [15]. The study protocol has been duly reviewed and approved by the institutional ethical committee (Ethical approval no: PUIEC/2018/113/A/9/01).

Laterosporulins Production and Purification

Laterosporulin (LS) and laterosporulin 10 (LS10), class IId bacteriocins described earlier [13, 14] were produced from Brevibacillus strains GI9 and SKDU10, respectively, in large quantity. Primary culture was prepared in 50 ml of nutrient broth (NB, Himedia, India) medium by inoculating single colonies of Brevibacillus spp. strains GI9 and SKDU10. Upon incubation at 30 °C with shaking at 180 rpm for 24 h, it was used to inoculate 2 l flasks containing 1 l of NB. The culture was grown for 48 h at 30 °C and subsequently cell free supernatant was obtained. The peptide was extracted from supernatant using Diaion HP-20 (Supelco) resin as crude extract [13]. The crude extract was applied onto a manually packed and calibrated sephadex G-50 (GE Healthcare, USA). The elution was done in 50 mM NaCl at flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The active fractions were collected, pooled, concentrated and finally purified by HPLC (1260 Infinity, Agilent Technologies, USA) using a reverse phased, semi-preparative C18 column (250 mm × 10 mm × 150 Å, Venusil, Agilent technologies) as mentioned earlier [14]. This pure peptide was used for coating Ti or HA discs and antibiofilm studies against test strains.

Determination of Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity

Growth inhibition was tested against dental plaque isolates using well diffusion assay. Lyophilized laterosporulins, LS and LS10 were dissolved in MilliQ water (1 mg/ml stock) and stored at 4 °C before setting up the assay. Test strains were cultivated to obtain the optical density of 0.4–0.6 (OD600) in tryptone soya broth (TSB) for Streptococcus gordonii strain DIGK25 and BHI broth to cultivate S. mutans DIGK119. About 100 µl of twofold diluted culture was spread on TSA or BHI agar plates. Subsequently, wells were made on these agar plates with a borer and added with 80 µl of laterosporulins solutions (150 µg/ml). Plates were incubated at 37 °C and observed for the presence of inhibition zones upon overnight incubation (16 h) in duplicate. Biofilm formation was examined using the crystal violet-based microtiter plate assay [16]. As medium components have been documented to enhance the biofilm formation [17], strains were grown in TSB or BHI broth supplemented with different concentrations (0.2–2.5%) of glucose to determine optimum biofilm formation. To test biofilm inhibition, overnight incubated culture of test strains was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min and pellet obtained was washed and suspended to a final cell density of 2 × 107 CFU/ml in phosphate saline buffer (PBS). Inoculum (20 µl) was added to each well of microtitre plate and added with 5–150 µg/ml concentrations of LS and LS10 along with control (medium alone). The final volume was made to 200 μl with TSB or BHI broth supplemented with 1.5 and 2.0% glucose, respectively. Test strains were allowed to form biofilms at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, planktonic cells were removed by gently washing the wells twice with PBS and the adherent biomass was stained with filtered 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet at room temperature for 20 min. Any excess staining was removed by washing the wells three times with PBS. To quantify the biomass, the deposited crystal violet stain was solubilized in 70% ethanol and OD was measured at 595 nm wavelength in a microplate reader. Biofilm formation was expressed as a ratio of crystal violet-stained biofilms compared to the control.

Biofilm Formation Assay on Ti and HA Discs

Sterile Ti and HA discs were placed in each well of a 12-well plate and immersed in 2 ml of TSB or BHI broth supplemented with 1.5 and 2.0% glucose used to grow S. gordonii strain DIGK25 and S. mutans DIGK119 to obtain optimal biofilm. Biofilm experiments were performed on discs that were treated with and without saliva. Pooled human whole saliva from six healthy individuals was utilized for pretreatment of discs to simulate tooth enamel surface present in oral cavity. Salivary collection and preparation for disc treatment was carried according to a reported protocol [18]. No food or beverages were consumed by volunteers to donate saliva except water during 2 h prior to saliva collection session. Non-smokers and individuals with no history of the use of antibiotics for the past three months were screened for donation of salivary samples. Collected saliva was prepared by mixing native, pooled saliva with glycerol (10% as a cryopreservative) in a 3:1 ratio and was stored at − 20 °C before experimentation [19]. The whole saliva collected was filtered through 0.22 μm syringe filters (Millipore, USA) and used in biofilm experiments to simulate the oral conditions in vitro. Ti and HA discs were soaked in this filter sterilized saliva and incubated for 3 h at RT. They were gently rinsed with sterile phosphate buffer and the wells were inoculated with 50 µl of selected strains containing 106 cfu/ml. Subsequently, increasing concentration of the laterosporulins (5–150 µg/ml) were added in to the wells and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Following incubation, discs were transferred into wells of another plate, washed thrice with sterile water to remove the planktonic cells and stained with crystal violet to determine biofilm formation. Wells containing only medium and untreated (with saliva) discs were used as controls. Similar protocol was adopted for biofilm inhibition studies on laterosporulins coated Ti and HA discs. Uncoated discs were used as control for the same.

Immobilization of Bacteriocins onto the Surface of Ti and HA Discs

Ti discs were polished with abrasive paper of different grit sizes and cleaned with 95% ethanol followed by deionized water. The samples were etched and hydroxylated in the acid piranha solution [20]. The piranha solution was freshly prepared just before the application at room temperature by transferring sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 75 ml) into a clean chemical glass container. 25 ml of 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added through the wall carefully and very slowly to prevent overheating of the solution. After 20 min of cooling the solution, clean Ti disc specimens were soaked in piranha solution for 20, 30 and 40 min duration [21]. Subsequently, discs were removed from the solution, thoroughly washed in distilled water and air dried for 2 h at room temperature. HA discs being porous in structure were not etched chemically with piranha solution, but were etched with 37% phosphoric acid to clean the surface of any organic debris and enhance the surface interaction with the peptide. The Ti and HA discs were dip coated in individual laterosporulin solutions (1 mg/ml) at room temperature. Coated discs were placed individually in each well of 12-well plates containing 3 ml of calcifying solution and maintained on a shaker incubator (New Brunswick Scientific, USA) at 60 °C and 75 rpm for 24 h. Subsequently, discs were removed, rinsed with double deionized water and air dried [22]. The coated Ti discs and HA discs were autoclave sterilized (121 °C for 15 min). Surface activated Ti and HA discs without coating by laterosporulins were also autoclaved and used as control specimens for various biofilm experiments.

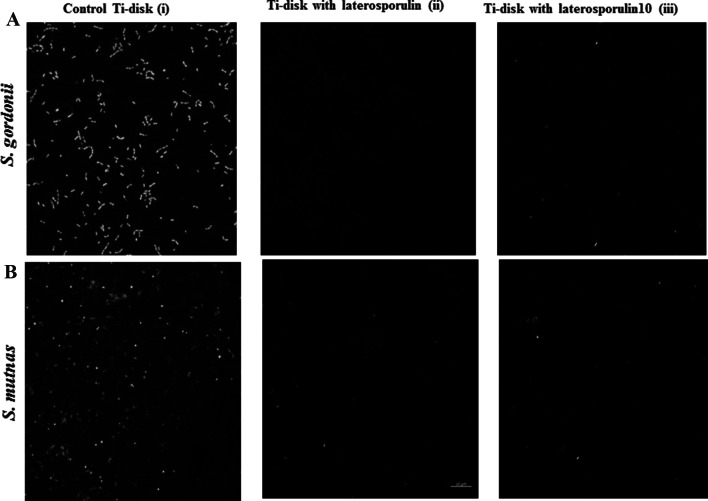

Confocal Microscopic Analysis of Laterosporulins Effect on Biofilms

Streptococcus gordonii strain DIGK25 and S. mutans strain DIGK119 were used to test biofilm formation on control Ti discs and Ti discs coated with both laterosporulins. The viability of cells in biofilm was assessed by fluorescence microscopy. Discs were placed in individual wells of a 12-well plate. Each well containing 2 ml of TSB with 1.5% glucose or BHI broth supplemented with 2.0% glucose was used to grow S. gordonii strain DIGK25 or S. mutans strain DIGK119, respectively. Upon incubation, discs were washed with sterile MQ-water to remove planktonic cells. Afterwards, discs were replaced into individual wells of another 12-well plate and stained with live/dead staining kit (Invitrogen, USA). The stain was freshly prepared by adding 150 µl of SYTO-9 (10 µM stock) and 75 µl of propidium iodide (PI) (100 µM stock) in 1275 µl of 0.9% NaCl to make final volume to 1.5 ml. Plates were incubated at room temperature in dark for 15 min. Each Ti disc was carefully positioned on a glass slide covered with mounting oil and observed under a reverse light fluorescence microscope equipped with a digital camera [23].

Statistical Analysis

All experiments in this study were carried out in triplicate and presented in the form of mean and the standard deviation (SD, ±) showed as error bars. Further, statistical significance was calculated using student’s t-test and a p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

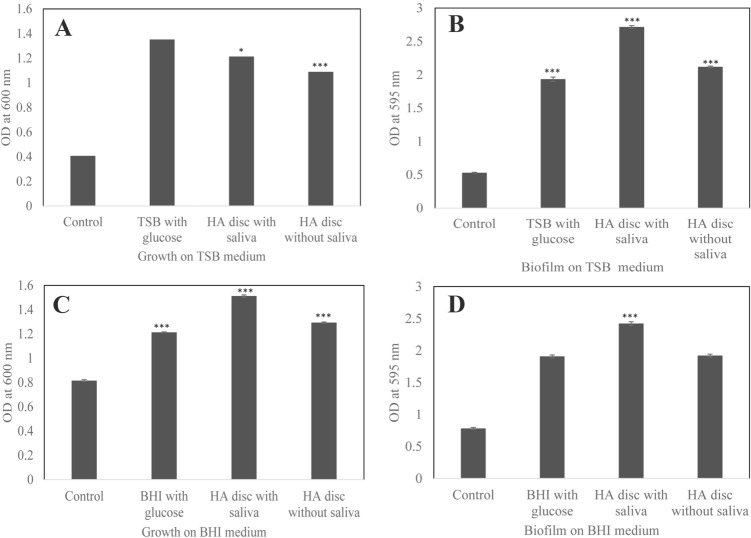

The present study was carried out to enhance the antimicrobial properties of Ti disc by coating their surface with laterosporulins, class IId bacteriocins from Brevibacillus spp. exhibiting human defensin analogue structure [13, 14]. The test strains used in this study were isolated from human dental plaque sample plated on different media. Strain DIGK25 was isolated on TSA and DIGK119 was on BHI agar medium and were identified as S. gordonii and S. mutans, respectively, based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis (both exhibiting > 99% identity). It is considered that Streptococcus species are the predominant early colonizers which form the primary biofilm on tooth surfaces and serve as a binding site for late colonizers such as Porphyromonas gingivalis that coaggregate as a secondary colonizer in mature dental plaque biofilms [24, 25]. Thus, we have selected the isolates S. gordonii strain DIGK25 and S. mutans strain DIGK119 as representative isolates of commensal and opportunistic pathogens, respectively for biofilm formation studies. Strains S. gordonii DIGK25 and S. mutans DIGK119 exhibited increase in growth with the addition of 1.5% and 2.0% glucose, respectively (Fig. 1a, c). Similarly, both strains displayed ability to form 2–3 fold higher biofilms in the presence of glucose in comparison to respective media controls (Fig. 1b, d). Biofilm formation was about 10% higher on Ti discs for S. gordonii DIGK25 in comparison to strain S. mutans DIGK119. However, the biofilm formation of strain S. gordonii DIGK25 was found to be 20% lesser on Ti discs without saliva treatment (Fig. 1b). S. mutans strain DIGK119 also showed increased biofilm formation on Ti disc that was treated with saliva (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Growth and biofilm formation ability by dental plaque streptococcal isolates in growth medium with the addition of 1.5% glucose and on Ti discs with or without saliva coated. a Growth of strain S. gordonii DIGK25. b Biofilm formation by S. gordonii strain DIGK25. c Growth of strain S. mutans DIGK119. d Biofilm formation by S. mutans strain DIGK119. Control is only growth medium. (p value indicates statistical difference between control and treated samples *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, and ***p < 0.0005)

Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity of Laterosporulins

Both LS and LS10 were tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of S. gordonii strain DIGK25 and S. mutans strain DIGK119. Though laterosporulins displayed broad spectrum antibacterial activity [13, 14], growth of streptococcal isolates was not inhibited by LS upto150 µg/ml. Likewise, no inhibition was observed for S. gordonii strain DIGK25 by LS10 at 150 µg/ml, however, growth of strain S. mutans DIGK119 was inhibited at 150 µg/ml (data not shown). The concentrations used were more than to 5X MIC concentrations reported for standard indicator strain Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1430 (50.0 and 24.2 µg/ml of LS and LS10, respectively). As both laterosporulins were found to be non-hemolytic even at more than 5X MIC observed against the mentioned test strain [13, 14], we have tested biofilm inhibition ability of these laterosporulins against S. gordonii strain DIGK25 and S. mutans strain DIGK119 by microtitre plate assay. Results showed that both laterosporulins were able to inhibit the biofilm formation at less than 100 µg/ml concentration.

Inhibition of Biofilms by Coating Laterosporulins on Ti Discs

To coat laterosporulins, the surface of Ti discs were activated using piranha solution for 20, 30 and 40 min. Ti alloy can be nanotextured by simple oxidative treatment with a mixture of H2SO4/H2O2, depending upon the treatment time and generates a sponge-like texture consisting of a network of nanopits [21, 26]. The most valuable feature of treated surface is the presence of a large amount of hydroxyl groups on the surface that provide hydrophilic properties of the material, which causes enhanced adsorption of cationic peptides like laterosporulins [27, 28]. Subsequently, activated discs were incubated by submerging them in 1 mg/ml solution of laterosporulins for coating. The coated discs were sterilized and used for antibiofilm studies. Results of antibiofilm assays showed 90% inhibition of S. gordoni strain DIGK25 biofilm by Ti discs coated with LS and LS10 upon incubation in piranha solution for 30. No biofilm was observed on Ti discs that were coated with laterosporulins upon 40 min treatment with piranha solution (Fig. 2a, b). Similarly, biofilm inhibition of S. mutans strain DIGK119 was observed by both laterosporulins (Fig. 2c, d). However, LS was found to be marginally more effective than LS10. Among all treated discs, Ti discs coated with laterosporulins upon incubation with piranha solution for 40 min showed maximum inhibition. This may be presumed as due to increased surface activation as reported in previous studies [21] that resulted in enhanced absorption of laterosporulins. Though the peptide binding on the Ti disc surface was not demonstrated, the binding of laterosporulins clearly indicated by the inhibition of biofilm on surface of Ti discs in comparison to control experiments that showed significant biofilm formation (Fig. 1b, d). Their binding was also found to be stable as the laterosporulins were reported to be stable even after exposing to 121 °C [13, 14]. Further, saliva present in oral cavity has a huge bearing on the oral ecology in terms of its composition more so with the presence of proteases present in it, which may limit the applicability of the antimicrobial peptides. However, in our study, laterosporulins with three disulfide bonds resulting in the formation of a closed structure readily displayed resistance to protease activity [13, 14]. Further, laterosporulins may be utilized as a resource to develop synthetic analogues with enhanced antimicrobial activity.

Fig. 2.

Biofilm inhibition on Ti discs treated with piranha solution (20, 30 and 40 min time interval) and surface coated with laterosporulin. a Effect of LS on S. gordonii strain DIGK25. b Effect of LS10 on S. gordonii strain DIGK25. c Biofilm inhibition effect of LS on S. mutans strain DIGK119. d Effect of LS10 against S. mutans strain DIGK119 biofilm. Inset images provided are biofilm control and the laterosporulin coated (at 40 min) Ti disc antibiofilm activity (p value indicates statistical difference between control and treated samples **p < 0.005, and ***p < 0.0005)

Human β-defensins (HBDs) are small cationic peptides, that are constitutively expressed in human oral cavity, however, they were never reported to coat on Ti surface. In contrast, LL-37, another 37-residue antimicrobial peptide released from the precursor of human cathelicidin is well studied and has been effectively utilized to coat the Ti surfaces to enhance their antimicrobial characteristics, to reduce the incidence of peri-implant infections [29, 30]. In fact, chlorhexidine was also used to reduce the growth of S. gordonii on two different kinds of Ti surfaces i.e. anatase and rutile TiO2 [31]. A novel short Trp-rich peptide, known as Pac-525 exhibited the highest antibacterial activity against bacteria like S. sanguis, Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC10953 and P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 known to cause peri-implantitis. Furthermore, 0.5 mg/ml of Pac-525 caused a significant decrease in biofilm thickness and a decline in the percentage of live bacteria in 2-day-old P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 biofilms cultured on Ti surfaces, compared to 0.1% chlorhexidine [25]. The concentrations used are in agreement with the concentration of laterosporulins employed in the present study for coating the surface of Ti disc.

Biofilm Formation by S. gordonii strain DIGK25 and S. mutans Strain DIGK119 on HA Disc

We have further assessed the ability of test strains to form biofilm on HA disc as a simulation to tooth enamel surfaces present in oral environment. It is pertinent to mention that the surface mineral composition of synthetic HA and tooth enamel is almost alike and these have been used conventionally in experimental settings to model the tooth surface [32]. S. gordonii strain DIGK25 grew well on HA disc and formed extensive biofilm on HA discs treated with saliva as well as on disc without saliva treatment (Fig. 3a, b). In fact, S. gordonii strain DIGK25 formed extensive biofilm on HA disc coated with saliva with addition of glucose. Almost similar trend was observed for S. mutans strain DIGK119 for growth (Fig. 3c) and biofilm formation was higher on saliva treated disc in comparison to untreated disc (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Biofilm formation ability of dental plaque streptococcal strains in media (TSB and BHI added with 1.5 and 2.0% glucose, respectively) and on HA disc as simulated dental surface. a Growth of strain S. gordonii DIGK25. b Biofilm formation by S. gordonii strain DIGK25. c Growth of strain S. mutans DIGK119. d Biofilm formation by S. mutans strain DIGK119 (p value indicates statistical difference between control and treated samples *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.0005)

Effect of Coating HA Discs with Various Laterosporulins on Biofilm Formation

The surface of HA discs was activated using 37% phosphoric acid [33] and treated with 1 mg/ml concentration of both laterosporulins. Subsequently, inhibition of biofilm was assessed by both test strains. Both laterosporulins, LS and LS10 effectively inhibited the biofilm formation of S. gordonii strain DIGK25 (Fig. 4a). Whereas LS10 displayed minor difference with S. mutans strain DIGK119 (Fig. 4b). Overall, there was not much difference observed in biofilm inhibition with or without the treatment of saliva on HA discs for both laterosporulins. The findings from the biofilm inhibition experiments on HA discs further ascertained the antibiofilm activity of LS and LS10 in simulated oral conditions in laboratory as may exist on the biofilms on the tooth enamel surfaces in oral activity.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of biofilm formation by streptococcal strains on HA discs coated with laterosporulins. a Effect of coated discs on inhibition of S. gordonii strain DIGK25 biofilm b Inhibition of S. mutans strain DIGK119 (p value indicates statistical difference between control and treated samples ***p < 0.0005)

Florescence Microscopy of the Ti Disc Samples Coated with Laterosporulins

The untreated Ti discs revealed an active and uniform green fluorescence in case of S. gordonii strain DIGK25 biofilm (Fig. 5a(i)) as well as for S. mutans strain DIGK119 (Fig. 5b(i)) indicating their biofilm formation ability on surface of Ti discs. However, no fluorescence on LS coated Ti discs surface revealed inhibition of biofilms of strains S. gordonii DIGK25 (Fig. 5a(ii)) and S. mutans DIGK119 (Fig. 5b(ii)). Absence of green florescence was also observed on Ti surface treated with LS10 indicating the inhibition of biofilm by S. gordonii strain DIGK25 (Fig. 5a(iii)) and S. mutans strain DIGK119 (Fig. 5b(iii)). Absence of red fluorescence give an indication that no cell death occurred on Ti disc surface.

Fig. 5.

Confocal microscopy images of laterosporulins coated Ti discs on biofilm formation. a Biofilm of S. gordonii strain DIGK25 grown in TSB containing 1.5% glucose (i) Control Ti disc without coating, (ii) Ti disc coated with LS and (iii) Ti disc coated with LS10. b Biofilm of S. mutans strain DIGK119 in BHI with 2.0% glucose (i) Biofilm on control Ti disc, (ii) Ti disc coated with LS and (iii) Ti disc coated with LS10

Several anti-biofilm mechanisms of AMPs are reported in the literature, more so categorized under the following five mechanisms: (1) disruption or degradation of the membrane potential of biofilm embedded cells; (2) interruption of bacterial cell signaling systems; (3) degradation of the polysaccharide and biofilm matrix; (4) inhibition of the alarm one system to avoid the bacterial stringent response; (5) downregulation of genes responsible for biofilm formation and transportation of binding proteins direct antimicrobial activity of the adsorbed molecules may be responsible for the inhibition of biofilm formation [34]. In the current investigation as repeated washings of the coated discs were found to display antimicrobial activities indicating binding of the laterosporulins on Ti disc surface. This is supported by the fact that no protein was detected by BCA protein estimation from wash off solutions of coated discs. Thus, it is hypothesized that the surface modification with laterulosporulins on Ti surfaces resulted in irreversible binding on metal surface. However, more experiments are needed to elucidate the mechanism and demonstrate the effect directly.

Within the limitations of the study, it is concluded that improvising the Ti surfaces by coating with laterosporulins reduces the biofilm formation by streptococcal isolates on the metal surface. Such modified surfaces appear a novel promising strategy to reduce the peri-implantitis and associated dental implant failures. In addition, the effects of laterosporulins were also evaluated for inhibition of oral biofilm formation on HA discs, in vitro as a model material for replicating the human tooth enamel surfaces in laboratory settings. The major draw backs of eukaryotic AMPs include their susceptibility to proteolysis, low activity in physiological conditions and the high cost of their production. These conditions may be tackled by the use of laterosporulins upon carrying-out more in vivo experiments using animal models. This point towards the potential clinical applicability of laterosporulins in oral health and hygiene maintenance for patients suffering from dental disease conditions.

Acknowledgements

The financial research support grant was issued in the month of September, 2017 vide letter No. S&T&RE/RP/147/Sanc/09/217/1123-1129 by the Department of Science and Technology, Chandigarh(UT) for this investigation. DST-SERB also acknowledged.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethics, Consent and Permissions

The study protocol has been duly reviewed and approved by the institutional ethical committee (Ethical approval no: PUIEC/2018/113/A/9/01). Strains were deposited at MTCC, CSIR-Institute of Microbial Technology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Moraschini V, Poubel LA, Ferreira VF, BarbozaEdos S. Evaluation of survival and success rates of dental implants reported in longitudinal studies with a follow-up period of at least 10 years: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker ST, Beck-Broichsitter BE, Rossmann CM, Behrens E, Jochens A, Wiltfang J. Long-term survival of Straumann dental implants with TPS surfaces: a retrospective study with a follow-up of 12 to 23 years. Clin Implant Dent Relate Res. 2016;18:480–488. doi: 10.1111/cid.12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu YT, Mason SA, Wang HL. Biological implant complications and their management. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2014;16:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen P, Clem D, Cochran D, Froum S, McAllister B, Renvert S, Wang HL. Peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: a current understanding of their diagnoses and clinical implications. J Periodontol. 2013;84:436–443. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.134001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalia VC, Patel KSS, Kang YC, Lee J. Quorum sensing inhibitors as antipathogens: biotechnological applications. Biotech Adv. 2019;37:68–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaenhammer TR. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:39–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1574/6976.1993.tb00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalia VC. Quorum sensing inhibitors: an overview. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:224–245. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saini A, Kalia VC (2017) Potential challenges and alternative approaches in metabolic engineering of bioactive compounds in industrial setup. 10.1007/978-981-10-5511-9_19

- 9.Rončević T, Puizina J, Tossi A. Antimicrobial peptides as anti-infective agents in pre-post-antibiotic era? Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5713. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orapiriyakul W, Young PS, Damiati L, Tsimbouri PM. Antibacterial surface modification of titanium implants in orthopaedics. J Tissue Eng. 2018 doi: 10.1177/2041731418789838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chouirfa H, Bouloussa H, Migonney V, Falentin-Daudré C. Review of titanium surface modification techniques and coatings for antibacterial applications. Acta Biomater. 2018;83:37–54. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L-C, Chen L-Y, Wang L. Surface modification of titanium and titanium alloys: technologies, developments and future interests. Adv Eng Mater. 2020;22:1258. doi: 10.1002/adem.201901258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh PK, Solanki V, Sharma S, Thakur KG, Krishnan B, Korpole S. The intramolecular disulfide-stapled structure of laterosporulin, a class IIdbacteriocin, conceals a human defensin-like structural module. FEBS J. 2015;282:203–214. doi: 10.1111/febs.13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baindara P, Singh N, Ranjan M, Nallabelli N, Chaudhry V, Pathania GL, Sharma N, Kumar A, Patil PB, Korpole S. Laterosporulin10: a novel defensin like class IIdbacteriocin from Brevibacillus sp. strain SKDU10 with inhibitory activity against microbial pathogens. Microbiology. 2016;162:1286–1299. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urvashi SD, Sharma S, Pal V, Lal R, Patil P, Grover V, Korpole S. Bacterial populations in subgingival plaque under healthy and diseased conditions: genomic insights into oral adaptation strategies by Lactobacillus sp. strain DISK7. Ind J Microbiol. 2020;60:78–86. doi: 10.1007/s12088/019/00828/8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Toole G, Kaplan HB, Kolter R. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:49–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalia VC, Prakash J, KoulS RS. Simple and rapid method for detecting biofilm forming bacteria. Ind J Microbiol. 2017;57:109–111. doi: 10.1007/s12088-016-0616-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin JM, Ateia I, Paulus JR, Liu H, Fenn JC, Rickard AH, Kapila YL. Antimicrobial nisin acts against saliva derived multi-species biofilms without cytotoxicity to human oral cells. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:617. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitada K, Oho T. Effect of saliva viscosity on the coaggregation between oral streptococci and Actinomyces neaslundii. Gerodontology. 2012;29:e981–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albertia CJ, Saitob E, de Freitasb FE, Reisb DAP, Machadoc JPB, dos Reisa AG. Effect of etching temperature on surface properties of Ti6Al4V alloy for use in biomedical applications. Mater Res. 2019;22:e20180782. doi: 10.1590/1980-5373-MR-2018-0782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Variola F, Yi J, Richert L, Wuest JD, Rosei F, Nanci A. Tailoring the surface properties of Ti6Al4V by controlled chemical oxidation. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1285–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulkarni AA, Pushalkar S, Zhao M, et al. Antibacterial and bioactive coatings on titanium implant surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 2017;105:2218–2227. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta V, Singh S, Sidhu C, Grover V, Korpole S. Virgicin, a novel lanthipeptide from Virgibacillus sp. strain AK90 exhibits inhibitory activity against Gram-positive bacteria. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;35:133. doi: 10.1007/s11274-019-2707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang R, Li M, Gregory RL. Bacterial interactions in dental biofilm. Virulence. 2011;2:435–444. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.5.16140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li JY, Wang XJ, Wang LN, Ying XX, Ren X, Liu HY, Xu L, Ma GW. High in vitro antibacterial activity of Pac-525 against Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilms cultured on titanium. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:909870. doi: 10.1155/2015/909870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gostin PF, Helth A, Voss A, Sueptitz R, Calin M, Eckert J, Gebert A. Surface treatment, corrosion behavior, and apatite-forming ability of Ti-45Nb implant alloy. J Biomed Mater Res Part B. 2013;101B:269–278. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nazarov DV, Zemtsova EG, Solokhin AY, Valiev RZ, Smirnov VM. Modification of the surface topography and composition of ultrafine and coarse grained titanium by chemical etching. Nanomaterials (Basel, Switzerland) 2017;7:15. doi: 10.3390/nano7010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G, Mishra B, Epand RF, Epand RM. High-quality 3D structures shine light on antibacterial, anti-biofilm and antiviral activities of human cathelicidin LL-37 and its fragments. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838:2160–2172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra B, Wang G. Titanium surfaces immobilized with the major antimicrobial fragment FK-16 of human cathelicidin LL-37 are potent against multiple antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Biofouling. 2017;33:544–555. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2017.1332186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbour ME, Gandhi N, El-Turki A, O'Sullivan DJ, Jagger DC. Differential adhesion of Streptococcus gordonii to anatase and rutile titanium dioxide surfaces with and without functionalization with chlorhexidine. J Biomed Mater Res. 2009;90:993–998. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshinari M, Kato T, Matsuzaka K, Hayakawa T, Shiba K. Prevention of biofilm formation on titanium surfaces modified with conjugated molecules comprised of antimicrobial and titanium-binding peptides. Biofouling. 2010;26:103–110. doi: 10.1080/08927010903216572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z, de la Fuente-Núñez C, Shen Y, Haapasalo M, Hancock REW. Treatment of oral multispecies biofilms by an anti-biofilm peptide. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharouf N, Mancino D, et al. Effectiveness of etching by three acids on the morphological and chemical features of dentin tissue. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2019;20:915–919. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z, Shen Y, Haapasalo M. Antibiofilm peptides against oral biofilms. J Oral Microbiol. 2017;9:1327308. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2017.1327308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]