Abstract

Introduction

Amidst growing consensus that stakeholder decision-making during drug development should be informed by an understanding of patient preferences, the Innovative Medicines Initiative project ‘Patient Preferences in Benefit-Risk Assessments during the Drug Life Cycle’ (PREFER) is developing evidence-based recommendations about how and when patient preferences should be integrated into the drug life cycle. This protocol describes a PREFER clinical case study which compares two preference elicitation methodologies across several populations and provides information about benefit–risk trade-offs by those at risk of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) for preventive interventions.

Methods and analysis

This mixed methods study will be conducted in three countries (UK, Germany, Romania) to assess preferences of (1) first-degree relatives (FDRs) of patients with RA and (2) members of the public. Focus groups using nominal group techniques (UK) and ranking surveys (Germany and Romania) will identify and rank key treatment attributes. Focus group transcripts will be analysed thematically using the framework method and average rank orders calculated. These results will inform the treatment attributes to be assessed in a survey including a discrete choice experiment (DCE) and a probabilistic threshold technique (PTT). The survey will also include measures of sociodemographic variables, health literacy, numeracy, illness perceptions and beliefs about medicines. The survey will be administered to (1) 400 FDRs of patients with RA (UK); (2) 100 FDRs of patients with RA (Germany); and (3) 1000 members of the public in each of UK, Germany and Romania. Logit-based approaches will be used to analyse the DCE and imputation and interval regression for the PTT.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the London-Hampstead Research Ethics Committee (19/LO/0407) and the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (92_17 B). The protocol has been approved by the PREFER expert review board. The results will be disseminated widely and will inform the PREFER recommendations.

Keywords: rheumatology, preventive medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study has been developed by an international, multidisciplinary team of academic, clinical, pharmaceutical industry and patient partners, and provides an example of a rigorously designed treatment preference study that is informative for a range of stakeholders.

This study addresses both clinical and methodological research objectives, and the findings will contribute to both the development of efficient prevention strategies for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and the development of best practice on the integration of patient preferences into drug development.

This study involves a substantial sample size across several populations, allowing comparison of treatment preferences, psychological variables and sociodemographic information across populations in three European countries.

This is the first quantitative study of preferences for preventive treatments for RA involving a large sample of confirmed, rather than self-reported, first-degree relatives of patients with a clinician-confirmed diagnosis of RA.

This study recruits first-degree relatives indirectly via invitations passed on by patients with a confirmed diagnosis of RA and may therefore be open to selection bias at both patient and participant level.

Introduction

There is increasing agreement that decision-making by the pharmaceutical industry, regulators and health technology assessment bodies throughout the development of medical products should be informed by an understanding of patient preferences, and that guidance on best practice is required.1–4 This study is a case study for the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) project ‘Patient Preferences in Benefit-Risk Assessments during the Drug Life Cycle’ (PREFER). PREFER aims to strengthen patient-centric decision-making products by developing evidence-based recommendations to guide stakeholders on how and when patient preference studies should inform decision-making.

There are many methodological research questions that warrant further study in preference research.5 PREFER conducted a landscape assessment to identify the most important questions and pair them with clinical case studies, based on the disease under investigation, anticipated sample size and clinical research objectives. The results of these studies will inform the development of recommendations for conducting preference studies. The background to both the clinical and methodological questions addressed in the present study is outlined in the following sections.

Clinical background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common chronic destructive polyarthritis, affecting approximately 1% of the general population.6 7 Typical age of onset is between 40 and 60 years old, although it can begin at much younger and older ages. If untreated, RA causes joint damage and disability. RA is associated with significant extra-articular manifestations reducing life expectancy by approximately 10 years.8

It is not currently possible to cure RA and long-term treatment is usually required. Available treatments include conventional (c), biological (b) and targeted synthetic (ts) disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), with varying benefit–risk profiles. The mainstay of treatment is methotrexate, a relatively inexpensive cDMARD to which approximately one-third of patients respond well.9 For those who do not respond well to first-line treatment, the use of a combination of cDMARDs and the addition of more (expensive) bDMARDs may be employed. Prolonged use of cDMARDs and bDMARDs is associated with considerable risk, including risk of infection and of lung, liver and haematological toxicity.9

Very early treatment of RA is associated with improved outcomes.10 11 There is now an emerging research focus on treating ‘at risk’ individuals in the preclinical and earliest clinically apparent phases of RA12 13 to assess whether a relatively short course of therapy will prevent or delay the onset of RA. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations identify terminology to describe groups of participants appropriate for prospective trials: individuals without RA having (1) genetic risk factors for RA, (2) environmental risk factors for RA, (3) systemic autoimmunity associated with RA, (4) symptoms without clinical arthritis (arthralgia) or (5) unclassified arthritis.14

Two completed15 16 and five ongoing (APIPPRA,17 ARIAA,18 TREAT EARLIER,19 STAPRA,20 SToPRA21) proof-of-concept trials are assessing the effectiveness of drugs currently used to treat RA to prevent or delay the onset of RA in one or more of these ‘at risk’ groups. Novel immune tolerising therapies are also being investigated in another IMI project, ‘RheumaTolerance for Cure’.22

While members of the general population have a 1/100 probability of developing RA, first-degree relatives (FDRs; EULAR ‘at risk’ stages 1–2) of existing patients are four times more likely to develop RA in the future.23 FDRs are therefore likely candidates for preventive approaches. For example, the SToPRA trial (evaluating the preventive effectiveness of a 12-month course of hydroxychloroquine21) is recruiting asymptomatic FDRs of patients with RA and individuals attending health fairs who are autoantibody-positive (EULAR ‘at risk’ stages 1–3).

Understanding the treatment preferences of ‘at risk’ groups is especially important in preventive contexts, where there is uncertainty regarding treatment effectiveness and safety (as per standard patient preference studies), and also the individual’s baseline risk of developing RA in the future, the timeline for that risk and the likely future severity of disease. As prospective studies elucidate biomarkers predictive of RA development, risk stratification of healthy individuals is increasingly likely to facilitate early treatment and preventive interventions.24–26 As prevention research evolves, knowledge of the preferences of ‘at risk’ individuals around RA treatments repurposed for prevention and (as yet) hypothetical new ones will be valuable to inform the development and regulation of efficient and effective preventive interventions for RA.

It is also of value to understand treatment preferences in the general public who are asked to imagine being at an elevated risk of developing RA. The assessment of preferences of FDRs at increased risk of RA and a general population that is told to assume an increased risk of RA allows for comparisons between groups that are expected to vary in their familiarity with and understanding of RA.27 Public misperceptions around the identity and severity of RA are common.28 29

A small number of qualitative studies have explored perceptions of preventive intervention for RA,30–33 but quantitative evidence is limited.34 A discrete choice experiment (DCE) assessing preferences for preventive pharmacological interventions for RA of 288 self-reported FDRs recruited via the Amazon Mechanical Turk suggested that mode of administration may be an important determinant of preventive treatment acceptability.35 This finding was echoed in a subsequent study that included 30 self-reported FDRs.36 However, a best–worst scaling pilot study found that the effectiveness and risks of preventive treatments were more important than mode of administration for a small sample of 34 FDRs taking part in a prospective cohort study.37 Further quantitative evidence is needed in clinically validated populations and larger samples. The primary clinical objective of this preference study is therefore to establish the preferences of ‘at risk’ individuals (ie, children or siblings of confirmed patients with RA) and the general public for preventive therapies for RA.

Methodological background

PREFER has identified a number of methodological questions for which evidence is currently lacking. This case study will provide evidence to address several methodological questions in line with PREFER strategy. First, there is no consensus on which is the best method to gather quantitative treatment preference data, and multiple techniques ranging from simple ranking exercises to complex, resource-intensive trade-off methods are employed. PREFER seeks to assess how similar the results of simpler/faster/cheaper methods are compared with more rigorous/indepth/expensive preference methods involving the same set of treatment attributes. This case study will compare preferences for preventive treatments elicited by DCE38 and probabilistic threshold technique (PTT).39 40

In a typical DCE, respondents are asked to complete several ‘choice tasks’. Each consists of choosing between two or more alternatives that describe a treatment (or no treatment). The description of the treatment is based on its characteristics, or ‘attributes’. The individual’s preference for an alternative can be determined based on the values of the levels of the included attributes across the choice tasks. PTT has a similar, but simpler choice task as the DCE. Rather than varying all attribute levels according to an experimental design, individuals choose between a reference treatment profile and an alternative treatment where only one attribute is improved or made worse until the participant changes their choice from one profile to the other. The point at which the participant switches their choice is the threshold. PTT is simpler in that it does not require an experimental design, specialised analytical or design software, or complex multivariate conditional models. This study will determine the extent to which results using the PTT differ from results of the relatively complex DCE. The DCE attributes and levels will be determined first, and the PTT alternatives will be chosen based on the DCE attributes and levels, including which attribute to modify. The exact selection and formulation of the attributes included in both choice methods will be based on a previous qualitative research phase.

A further PREFER objective is to investigate the relationship between measures of psychological constructs and preference heterogeneity. In order to do so, this study will assess whether measures of psychological constructs (ie, perceived risk, beliefs about medicines, illness perceptions) can explain preference heterogeneity, as evidence in this area is limited.41 Other measures such as health literacy and numeracy might also explain preference heterogeneity and could impact preference construction (ie, leading to differences in choice consistency, certainty and so on)42 and will also be assessed.

The current case study will take place in the same format in the UK, Germany and Romania, enabling comparisons across countries, thus addressing a further PREFER methodological objective and elucidating the transferability of preferences across regions. Finally, as most current intervention trials in individuals at risk of RA are targeting patients with early symptoms (eg, joint pain) and elevated RA-related autoantibodies, the current case study will ask FDR participants to imagine they have started to develop joint symptoms and have had blood tests, which indicate that they are at high risk of developing RA within 2 years. Similarly, members of the general population will be asked to imagine the same scenario. This will allow assessment of whether the FDRs respond systematically differently from members of the general public. This will address PREFER questions related to both the generalisability of preferences from one specific population in a disease to different populations.

Methods and analysis

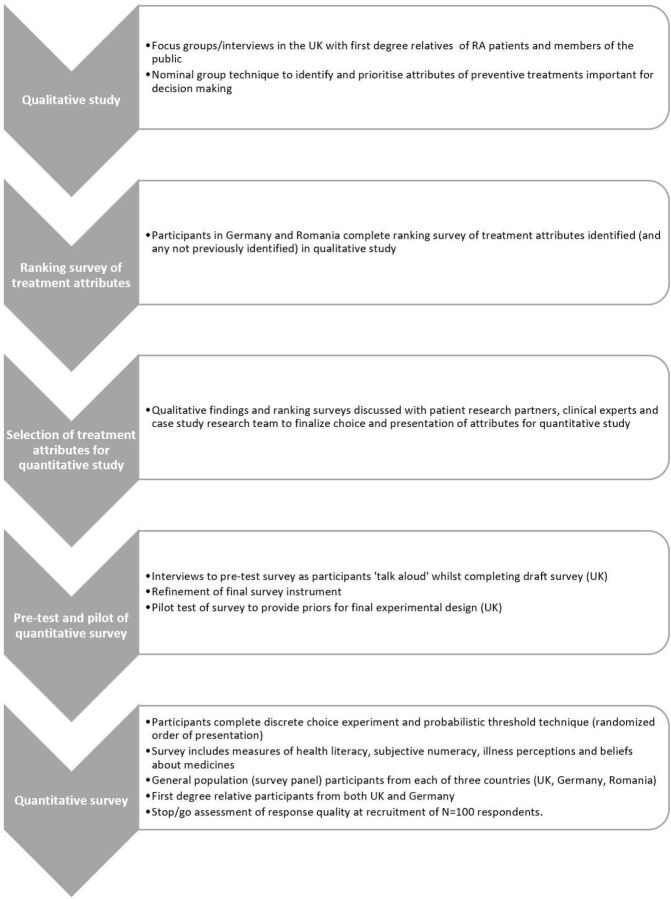

This study will consist of two phases. A focus group/interview study using nominal group technique (NGT)43 in the UK with confirmatory ranking surveys in Germany and Romania will be conducted to explore attributes relevant to decision-making about treatments to prevent RA, and inform the selection and definition of attributes to be used in a quantitative study. This will be followed by a stated preference survey to assess treatment preferences of FDRs and the general population (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

We will employ evidence-based guidelines and best practices for study design and conduct, including focus groups,44 NGT,43 and for preference study design and analysis.45 46

Focus group/interview study

The outcomes of the focus group/interview study will be (1) a description of themes that are important considerations for decision-making about preventive treatment for RA; and (2) a list of treatment attributes relevant for decision-making and their rank order.

We aim to conduct four focus groups: two with FDRs and two with the general population in the UK. Each focus group will have approximately five to seven respondents. Four focus groups are expected to be sufficient to generate attributes since focus groups have been shown to yield concept saturation after two to four group discussions.44 All participants will be aged 18 years or older. Focus group participants will be offered £20 as an incentive. Focus groups will take place at the University of Birmingham, UK.

Members of the general population will be invited to the focus group through an advert on community message boards and online research recruitment platforms. FDRs will be recruited indirectly, through patients with RA identified at outpatient clinics at participating sites. Patients with RA attending rheumatology clinic will be invited to pass on a study invitation to their FDRs. All focus group participants will provide informed consent before taking part, facilitated by a participant information sheet (PIS).

To increase consistency across focus groups, a semistructured interview guide with questions about characteristics that might be expected in a preventive treatment for RA will be developed. The guide will be developed with clinical expert input and an international panel of patient research partners and informed by a review of the literature. Any treatment attributes that have featured across previous studies of preferences for RA treatments that are not identified during the initial discussion will be introduced to participants for further discussion. NGT43 will be used to obtain rankings of attributes identified in the focus group by their relative importance to inform the preference study design.

We will ask focus group participants to imagine they have started to develop joint pain and have had a blood test that indicates they have a 40% risk to develop RA in the next 2 years. This is representative of participants included in current trials of preventive interventions for RA, whose risk of developing RA within 2 years is between 10% and 60% depending on the presence of other risk factors.47

The focus group discussions will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts will be analysed using the framework method.48 At least 20% of transcripts will be independently coded by multiple researchers to develop a coding framework with input from patient research partners. At least two researchers will independently code each transcript applying the agreed framework.

Analysis of transcripts will proceed at the same time as data collection. When there is consensus among the research team that thematic saturation has been achieved and no new treatment attributes are being identified, no new focus groups will be scheduled. The original list of attributes used for the ranking exercises in the NGT will then be included in a ranking survey for FDRs and members of the general public in Germany (n=30) and members of the general public in Romania (n=30). This survey aims to confirm/validate the selection of the most important treatment attributes across all countries involved in the quantitative study. The attribute rankings and focus groups findings will then be reviewed with clinical and methodological experts and patient partners to select those appropriate for inclusion in a DCE, and a representative range of levels for each attribute will be selected. Any high-ranking attributes that are not included in the DCE (eg, because of likely dominance) will be included (at a constant level) in the survey choice task setting.

Stated preference study

The attributes and levels identified above will be incorporated into a survey containing both DCE and PTT. Both approaches will assess preferences for RA preventive treatments by asking respondents to choose between treatment alternatives. Each treatment will be described in terms of its level of each attribute. The order of presentation (DCE followed by PTT, or vice versa) will be randomised.

The combinations of attribute levels that define each profile and the set of profiles in each choice question in a DCE are known as the experimental design. The experimental design must have statistical properties that allow estimation of the preference weights of interest. This study will use Ngene (ChoiceMetrics, Sydney, Australia) to construct a Bayesian D-efficient fractional-factorial experimental design.49 Prior information on the importance of the attributes will be based on previous literature and best guesses for a pilot study, and outcomes of initial analysis (conditional logit) of pilot data for the main survey.

Survey instrument

All participants will provide informed consent before completing the survey. Respondents will complete a demographic questionnaire and assess their perceived risk of developing RA. They will be asked to read a description of RA and risk factors for RA developed with clinical experts and patient partners. Respondents will then be asked to imagine they have started to develop joint pain and have had a blood test that indicates they have an elevated risk of developing RA in the next 2 years. This will be followed by evaluation questions, including warm-up and knowledge questions, to test participants’ understanding of the information presented. For example, the participant may be shown a risk grid to test understanding of percentages, with 3 persons selected and 97 persons not selected to test understanding of 3% or 3 in 100. This will be followed by either the DCE/PPT choice task questions, which will be preceded by a guided ‘walk through’ demonstration of a DCE/PTT choice task and some warm-up questions. To avoid carry-over effects from DCE to PTT or vice versa, respondents will then complete the Single Item Literacy Screener50 and the three-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale.51 This will be followed by a guided example and evaluation questions for the choice tasks of the second method, followed by the actual choice tasks. Participants will then complete the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire52 53 and the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire-General.54 On completion of the survey, participants will be provided with sources of additional information about RA and risk factors for RA.

The survey will be pretested in a convenience sample (n=15) using qualitative think aloud interviews. These participants will be paid £20/€20 in shopping vouchers. To inform the final experimental design and optimise statistical efficiency, a survey pilot will be conducted with 100 members of the general public in the UK.

Survey sample

We aim to recruit a total of 3500 participants who have not received a diagnosis of RA, including the following:

400 adults who are FDRs of an individual with a confirmed diagnosis of RA, UK.

100 adults who are FDRs of an individual with a confirmed diagnosis of RA, Germany.

1000 adults from the general population, UK survey panel.

1000 adults from the general population, Germany survey panel.

1000 adults from the general population, Romania survey panel.

All participants will be asked to assume an increased risk of developing RA in the next 2 years.

A priori sample size calculations represent a challenge in DCE experiments. Most published studies have a sample size of 100–300 respondents.55 However, the minimum sample size depends on several criteria, including question format, choice task complexity, desired precision of results and subgroup analyses.46 56 A method for computing sample size was proposed by de Bekker-Grob et al57; however, as the article highlights, there is no analytical solution or power calculation that can be used to determine the appropriate sample size for a DCE unless enough information to inform the selection of priors exists.

There is no specific power calculation to determine sample size in PTT studies without knowing the expected threshold value a priori. Most PTT studies are conducted with 100 or fewer respondents, and substantially smaller samples (between 20 and 42 respondents) have been used successfully in previous studies.57–60 Given the lack of clear guidance on sample size estimation for PTT, we assume that a minimum sample size of 50 per PTT choice set would be needed to estimate a threshold value in each threshold exercise. To account for potential heterogeneity, a minimum total sample size of 100 will be considered sufficient to answer the primary objective. A target sample size of 200 is sufficient for the purposes of conducting subgroup analyses.

A sample of 250 FDRs should provide enough information to address the key clinical research objective with acceptable precision.55 An increased sample size of 400 will allow increased precision of estimates for other comparisons. Based on the sample size requirements for both methods and accounting for the number of additional methodological research questions this study anticipates to answer, a sample size of 1000 from a general population panel in each country should provide enough information to enable comparisons across groups and methods with acceptable precision.

Sample identification and eligibility

FDRs will be recruited through patients with a confirmed diagnosis of RA identified via rheumatology clinics. A letter explaining the study and requesting that patients invite an FDR to participate in the study will be given to patients during routine appointments or via mail. This letter will include a study invitation and PIS to pass on to an FDR. The invitation will contain a link to the online survey. The first section of the survey will be the PIS and online consent form. FDR survey participants will be offered an incentive (£5/€5 online gift voucher).

The general population samples will be recruited though online survey panels. Potential respondents will receive an email survey invite with a unique password-protected link to the online survey. The general population sample composition will match the expected FDR sample in terms of age and gender. The initial questions of the survey will be used to confirm the respondent’s eligibility. Eligible respondents will be provided the PIS and asked to provide anonymous electronic informed consent to participate. After completing the survey, panel members will be credited with panel points (equivalent to approximately €2–3 for a 30 min online survey).

Statistical considerations and data analysis

The main outcomes of the stated preference study will be the (1) relative preference weights for levels of treatment attributes; (2) estimated risk equivalents (maximum acceptable risk (MAR) and minimum acceptable benefit (MAB)) for changes in treatment attributes; and (3) potential treatment shares.

For the DCE, a logit-based analysis strategy will be conducted to estimate preferences for attributes of RA prevention therapies, including random parameters logit (RPL) modelling and latent class analyses (LCA). Final decisions on the modelling procedure will be made once data collection has been completed. This decision will be based on model fit and clinical interpretive values. Different models might be used to answer the different research questions in this case study. PTT data will be analysed using imputation and interval regression. The MAR/MAB values for benefits and risks will be calculated and allow comparison between DCE and PTT methods. Heterogeneity of preferences and the impact of participant characteristics (eg, demographics, RA knowledge, psychological instruments) will be investigated by applying appropriate statistical models including LCA for the DCE and/or subgroup analyses for the DCE (RPL) and PTT methods. For the DCE, only the potential treatment shares of currently existing preventive treatment will be calculated. All results described above will be formally compared between the three countries and between FDRs and the general population.

The results of the DCE and PTT will be compared qualitatively and quantitatively. From a quantitative perspective, the MAR and/or MAB will be calculated using each method for a particular benefit and risk attribute over the same range. This allows the average MAR/MAB value and associated 95% CIs to be directly compared. Next, the conditional relative importance of the benefits and harms will be compared across methods. As these methods would evaluate heterogeneity somewhat differently (DCE using LCA/RPL vs PTT categorising individual preferences), the comparison of heterogeneity of preferences will be qualitative. The extent to which DCE and PTT results would result in different decisions will be assessed using interviews with stakeholders. Additionally, comparisons will be made regarding logistics of both methods with respect to budget, time and perceived cognitive load (based on evaluation questions after each method).

Patient and public involvement

Patient partners in previous projects highlighted the importance of the clinical objectives of this study. Seven patient research partners provide input on all aspects of this study, including development of methodological objectives, choice of methods, recruitment procedures, study documents, focus group discussion guide, selection of attributes and levels, selection of psychological measures, survey design and content, interpretation of results, and public dissemination of project findings.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

It is possible (though unlikely61) that participants and patients approached to recruit FDRs might be concerned by the prospect of an enhanced risk of developing RA. We will provide participants with an information booklet developed as part of the EuroTEAM project62 and which discusses issues around being at risk of RA. English and German versions are currently available. Sources of further information and contact details for support will also be provided.

We will ensure that focus group participants are identified by a participant number, not by name, on both audio recordings and transcripts to protect their privacy. All survey responses are anonymous. FDRs who complete the survey and wish to receive payment will be directed to an independent landing page so they can provide email addresses to facilitate payment without the addresses being linked to survey responses.

Regulatory and protocol compliance

This study has been approved by the London-Hampstead Research Ethics Committee (19/LO/0407) and the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (92_17 B). The protocol has also been reviewed and approved by the PREFER expert review board and steering committee. The study will be conducted in compliance with this protocol, guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care, and the Data Protection Act 1998. Personal data protection in this study will be compliant with the European Union General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 and the Information Security Policies of the Universities of Birmingham and Erlangen.

Publication and dissemination policy

Publication of study results will be shared with patient organisations as lay summaries and submitted to peer-reviewed journals in accordance with the PREFER consortium agreement and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommendations.63

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patient research partners who have contributed to the design of this study and the support of the Birmingham Rheumatology Research Patient Partnership. The authors also acknowledge input from the extended team supporting the PREFER RA case study, particularly Ardine de Wit and Meredith Smith.

Footnotes

Twitter: @DrMarieFalahee

Contributors: MF, GS, RLD, LVM, CR, ME, KB, ST-L, UK, BH, JV and KR made substantial contributions to the conception, planning and writing of this study protocol. The initial draft was prepared by GS, MF, RLD JV and CR. MF, GS, RLD, LVM, CR, ME, KB, ST-L, UK, BH, JV and KR revised the protocol critically and approved the final version. MF, GS, RLD, LVM, CR, ME, KB, ST-L, UK, BH, JV and KR accept responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of this protocol.

Funding: This study is part of the PREFER project (Patient Preferences in Benefit-Risk Assessments during the Drug Life Cycle). The PREFER project has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement number 115966. This Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA. KR is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre.

Competing interests: MF, GS, LVM, ME, KB, UK, BH and JV have no competing interests to declare. RLD is employed by Janssen Pharmaceuticals and is a shareholder of Johnson & Johnson. CR is an employee and shareholder of Eli Lilly and Company. ST-L is employed by Sanofi R&D and is a shareholder of Sanofi. KR reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Lilly, personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, personal fees from UCB, personal fees from Janssen, and personal fees from Roche Chugai, outside the submitted work.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods and analysis section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.de Bekker-Grob EW, Berlin C, Levitan B, et al. Giving patients’ preferences a voice in medical treatment life cycle: the PREFER public–private project. Patient 2017;10:263–6. 10.1007/s40271-017-0222-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook NS, Cave J, Holtorf A-P. Patient preference studies during early drug development: aligning stakeholders to ensure development plans meet patient needs. Front Med 2019;6:82. 10.3389/fmed.2019.00082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho MP, Gonzalez JM, Lerner HP, et al. Incorporating patient-preference evidence into regulatory decision making. Surg Endosc 2015;29:2984–93. 10.1007/s00464-014-4044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vass CM, Payne K. Using discrete choice experiments to inform the benefit-risk assessment of medicines: are we ready yet? Pharmacoeconomics 2017;35:859–66. 10.1007/s40273-017-0518-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levitan B, Hauber AB, Damiano MG, et al. The ball is in your court: agenda for research to advance the science of patient preferences in the regulatory review of medical devices in the United States. Patient 2017;10:531–6. 10.1007/s40271-017-0272-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Symmons D, Turner G, Webb R, et al. The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom: new estimates for a new century. Rheumatology 2002;41:793–800. 10.1093/rheumatology/41.7.793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silman AJ, Pearson JE. Epidemiology and genetics of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res 2002;4:S265–72. 10.1186/ar578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dougados M. Comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2016;28:282–8. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Olivo MA, et al. Methotrexate for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;6:Cd000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nell VPK, Machold KP, Eberl G, et al. Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2004;43:906–14. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raza K, Buckley CE, Salmon M, et al. Treating very early rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006;20:849–63. 10.1016/j.berh.2006.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raza K, Klareskog L, Holers VM. Predicting and preventing the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2016;55:1–3. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Steenbergen HW, da Silva JAP, Huizinga TWJ, et al. Preventing progression from arthralgia to arthritis: targeting the right patients. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018;14:32–41. 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerlag DM, Raza K, van Baarsen LGM, et al. EULAR recommendations for terminology and research in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis: report from the study Group for risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:638–41. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bos WH, Dijkmans BAC, Boers M, et al. Effect of dexamethasone on autoantibody levels and arthritis development in patients with arthralgia: a randomised trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:571–4. 10.1136/ard.2008.105767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerlag DM, Norris JM, Tak PP. Towards prevention of autoantibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis: from lifestyle modification to preventive treatment. Rheumatology 2016;55:607–14. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Laith M, Jasenecova M, Abraham S, et al. Arthritis prevention in the pre-clinical phase of RA with abatacept (the APIPPRA study): a multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial protocol. Trials 2019;20:429. 10.1186/s13063-019-3403-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abatacept reversing subclinical inflammation as measured by MRI in AcpA positive arthralgia (ARIAA). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02778906. Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02778906

- 19.Niemantsverdriet E, Dakkak YJ, Burgers LE, et al. Treat early arthralgia to reverse or limit impending exacerbation to rheumatoid arthritis (treat earlier): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial protocol. Trials 2020;21:862. 10.1186/s13063-020-04731-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Boheemen L, et al. The statins to prevent rheumatoid arthritis (STAPRA) trial: clinical results and subsequent qualitative study, a mixed method evaluation. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strategy to Prevent the Onset of Clinically-Apparent Rheumatoid Arthritis (StopRA): US national library of medicine. Available: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02603146

- 22.RheumaTolerance for cure (RTCure). Available: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/777357

- 23.Koumantaki Y, Giziaki E, Linos A, et al. Family history as a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 1997;24:1522–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolfenbach JR, Deane KD, Derber LA, et al. A prospective approach to investigating the natural history of preclinical rheumatoid arthritis (rA) using first-degree relatives of probands with RA. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1735–42. 10.1002/art.24833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arthritis-checkup: study of an early detection of the disease. Available: http://www.arthritis-checkup.ch/index_gb.html

- 26.Pre-clinical evaluation of novel targets in RA (Prevent-RA). Available: http://www.preventra.net/

- 27.Veldwijk J, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Kihlbom U, et al. How psychological distance of a study sample in discrete choice experiments affects preference measurement: a colorectal cancer screening case study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2019;13:273–82. 10.2147/PPA.S180994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simons G, Belcher J, Morton C, et al. Symptom recognition and perceived urgency of help-seeking for rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases in the general public: a mixed method approach. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:633–41. 10.1002/acr.22979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simons G, Mason A, Falahee M, et al. Qualitative exploration of illness perceptions of rheumatoid arthritis in the general public. Musculoskeletal Care 2017;15:13–22. 10.1002/msc.1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stack RJ, Stoffer M, Englbrecht M, et al. Perceptions of risk and predictive testing held by the first-degree relatives of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in England, Austria and Germany: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010555. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simons G, Stack RJ, Stoffer-Marx M, et al. Perceptions of first-degree relatives of patients with rheumatoid arthritis about lifestyle modifications and pharmacological interventions to reduce the risk of rheumatoid arthritis development: a qualitative interview study. BMC Rheumatol 2018;2:31. 10.1186/s41927-018-0038-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falahee M, Simons G, Buckley CD, et al. Patients’ perceptions of their relatives’ risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis and of the potential for risk communication, prediction, and modulation. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:1558–65. 10.1002/acr.23179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munro S, Spooner L, Milbers K, et al. Perspectives of patients, first-degree relatives and rheumatologists on preventive treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative analysis. BMC Rheumatol 2018;2:18. 10.1186/s41927-018-0026-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falahee M, Finckh A, Raza K, et al. Preferences of patients and at-risk individuals for preventive approaches to rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 2019;41:1346–54. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison M, Spooner L, Bansback N, et al. Preventing rheumatoid arthritis: preferences for and predicted uptake of preventive treatments among high risk individuals. PLoS One 2019;14:e0216075. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison M, Bansback N, Aguiar M, et al. Preferences for treatments to prevent rheumatoid arthritis in Canada and the influence of shared decision-making. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39:2931–41. 10.1007/s10067-020-05072-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finckh A, Escher M, Liang MH, et al. Preventive treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: issues regarding patient preferences. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016;18:51. 10.1007/s11926-016-0598-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, et al. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 2014;32:883–902. 10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Llewellyn-Thomas H, technique T. Threshold technique. : Encyclopedia of medical decision making. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2009: 1134–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauber B, Coulter J. Using the threshold technique to elicit patient preferences: an introduction to the method and an overview of existing empirical applications. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2020;18:31–46. 10.1007/s40258-019-00521-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russo S, Jongerius C, Faccio F, et al. Understanding patients’ preferences: a systematic review of psychological instruments used in patients’ preference and decision studies. Value Health 2019;22:491–501. 10.1016/j.jval.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veldwijk J, van der Heide I, Rademakers J, et al. Preferences for vaccination: does health literacy make a difference? Med Decis Making 2015;35:948–58. 10.1177/0272989X15597225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hiligsmann M, van Durme C, Geusens P, et al. Nominal group technique to select attributes for discrete choice experiments: an example for drug treatment choice in osteoporosis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:133–9. 10.2147/PPA.S38408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR good research practices for conjoint analysis task force. Value Health 2011;14:403–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reed Johnson F, Lancsar E, Marshall D, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health 2013;16:3–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van de Stadt LA, Witte BI, Bos WH, et al. A prediction rule for the development of arthritis in seropositive arthralgia patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1920–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, et al. The single item literacy screener: evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:21. 10.1186/1471-2296-7-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McNaughton CD, Cavanaugh KL, Kripalani S, et al. Validation of a short, 3-Item version of the subjective Numeracy scale. Med Decis Making 2015;35:932–6. 10.1177/0272989X15581800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, et al. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 2006;60:631–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Broadbent E, Wilkes C, Koschwanez H, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the brief illness perception questionnaire. Psychol Health 2015;30:1361–85. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1070851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 1999;14:1–24. 10.1080/08870449908407311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marshall D, Bridges JFP, Hauber B, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health - how are studies being designed and reported?: an update on current practice in the published literature between 2005 and 2008. Patient 2010;3:249–56. 10.2165/11539650-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Louviere J, Hensher D, Swait J. Stated choice methods; analysis and application. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, et al. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient 2015;8:373–84. 10.1007/s40271-015-0118-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steures P, Berkhout JC, Hompes PGA, et al. Patients’ preferences in deciding between intrauterine insemination and expectant management. Hum Reprod 2005;20:752–5. 10.1093/humrep/deh673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sung L, Feldman BM, Schwamborn G, et al. Inpatient versus outpatient management of low-risk pediatric febrile neutropenia: measuring parents' and healthcare professionals' preferences. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3922–9. 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dales RE, O'Connor A, Hebert P, et al. Intubation and mechanical ventilation for COPD: development of an instrument to elicit patient preferences. Chest 1999;116:792–800. 10.1378/chest.116.3.792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marshall AA, Zaccardelli A, Yu Z, et al. Effect of communicating personalized rheumatoid arthritis risk on concern for developing RA: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:976–83. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Towards early diagnosis and biomarker validation in arthritis management. final report. FP7-HEALTH project ID 305549. Available: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/305549/reporting

- 63.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) . Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals, 2019. Available: http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.