Abstract

Assessment of programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the definite diagnostic test to guide treatment for patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Intratumoral heterogeneity and discrepancy of PD-L1 expression between primary and metastatic lesions may increase the risk of tumor misclassification. We performed a retrospective study of the Foundation Medicine, Inc clinical database on lung cancer cases that were evaluated for PD-L1 expression by IHC in the context of routine care. All cases were assessed with the Food and Drug Administration-approved 22C3 pharmDx assay and scoring system. 15,028 lung cancer cases, including 8285 primary tumors and 6743 unmatched metastatic lesions were analyzed. Metastatic lesions (mets) were more frequently high positive (tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥50%) for PD-L1 expression than primary lesions (33.8% vs 28.4%; OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.37; p<0.001). Higher levels in mets than primaries were seen in samples from lymph nodes, pleural fluid, soft tissue and adrenal gland but not in those from liver, brain and bone. Metastatic lesions of patients with non-squamous histology were more likely to have TPS ≥50% in comparison with primary (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.49; p<0.001), but this was not the case for patients with squamous histology (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.06; p=0.197). PD-L1 expression varies with respect to histologic subtype, sampling site and gender, but is generally higher in metastatic sites. This observation may affect future patient management and trial design.

Keywords: biomarkers, tumor, immunohistochemistry, immunotherapy, lung neoplasms, programmed cell death 1 receptor

Background

Many patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) lack targetable driver mutations and so, immunotherapy has become integrated into their first-line therapeutic options. KEYNOTE-024 trial showed that patients with high programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥50% have significantly improved clinical outcomes when treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy.1 Anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) therapy has, therefore, established PD-L1 expression assessment by immunohistochemistry (IHC) as routine practice in lung cancer as well as other tumor types. Despite its promising applications, detection of PD-L1 expression varies among different sampling sites, complicating therapeutic decisions.2–5 Intratumoral heterogeneity and discrepancy of PD-L1 expression between primary and metastatic lesions have been reported in several studies.2 5 In the clinical setting, metastatic sites are often the only accessible source for PD-L1 evaluation. Hence, validation of the concordance in PD-L1 TPS between primary and metastatic sites is necessary to eliminate the risk of tumor misclassification.6 Here, we used the Foundation Medicine, Inc (FMI) PD-L1 IHC database to assess real-world potential differences in PD-L1 protein expression, as measured by PD-L1 TPS, between primary and metastatic lesions of patients with lung cancer. For our comparisons we used the ≥50% cut-off, as this has been previously shown to have the highest level of reproducibility between pathologists.7

Methods

Approval for this study, including a waiver of informed consent and a HIPAA waiver of authorization, was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 20152817). A retrospective data analysis of the FMI clinical database was conducted on lung cancer cases that were assessed for PD-L1 expression in the context of routine care. All samples were stained with the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx assay at FMI North Carolina laboratory. PD-L1 expression was evaluated and scored with the TPS scoring methodology: TPS=Number of PD-L1 positive tumor cells/(Total number of PD-L1 positive + PD-L1 negative tumor cells) × 100%. A tumor was considered PD-L1 high if TPS ≥50%. Multivariable logistic-regression models were used to examine the relationship between PD-L1 expression level and other variables including age, gender, sampling site and histologic subtype. Since this is a real-world dataset, outcome variables and some clinical variables like stage and grade were not collected by the FMI lab since that is not required to provide clinical testing.

From the eight different subtypes, we focused on two; lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) and non-squamous NSCLC that includes lung adenocarcinoma, NSCLC not otherwise specified and lung large cell carcinoma. In all tests, two-sided p values of <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism V.8 software and RStudio V.4.0.1.

Results

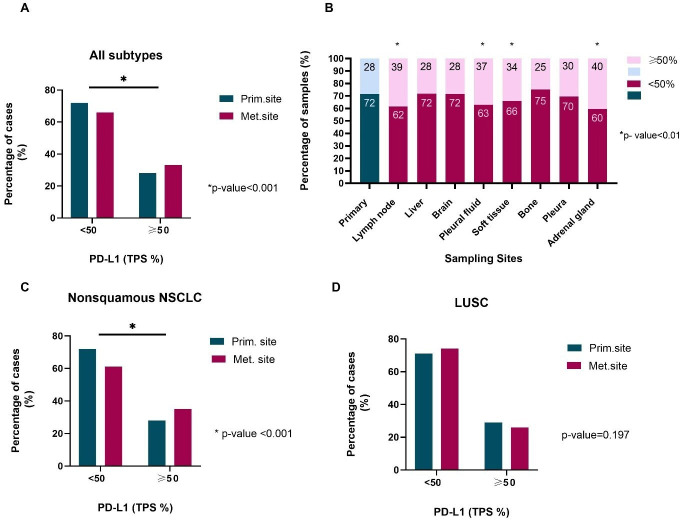

A total of 15,028 samples from 7599 male and 7429 female patients with lung cancer, with a median age of 68 years (range 19–90) were analyzed; 8285 samples were from primary and 6743 from metastatic lesions, representing 55 different metastatic sites (table 1). In general, samples obtained from metastatic lesions were more likely to be PD-L1 high compared with those from the primary site (33.8% vs 28.4%; OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.37; p<0.001; table 2, figure 1A). The absolute difference between the rate of PD-L1 high patients when PD-L1 TPS was measured at a metastatic site, and the average rate of PD-L1 high patients in the study population, when PD-L1 TPS was measured at both primary and metastatic sites, was 2.9% (33.8% vs 30.8%; 95% CI, 1.6% to 4.3%). Substantial heterogeneity was observed across different metastatic sites. Among the eight most common metastatic sites, high PD-L1 expression was, statistically significantly, more frequent in samples obtained from lymph nodes (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.43 to 1.74; p<0.001), pleural fluid (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.78; p<0.001), soft tissue (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.58; p=0.007) and adrenal gland (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.30 to 2.22; p<0.001) compared with primary site (table 2, figure 1B). This was not the case with metastatic lesions from pleura (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.89 to 1.40; p=0.343), liver (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.83 to 1.16; p=0.835), brain (OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.85 to 1.18; p=0.994) and bone (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.67 to 1.04; p=0.101).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics

| Characteristics | Primary site | Metastatic site |

| (n=8285), n (%) | (n=6743), n (%) | |

| Age, years | ||

| Median (range) | 69 (23–90) | 67 (19–90) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 4175 (50.4) | 3424 (50.8) |

| Female | 4108 (49.6) | 3316 (49.2) |

| NA | 2 (0.02) | 3 (0.04) |

| Histologic type | ||

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 5072 (61.2) | 4578 (70.5) |

| LUSC | 2099 (25.3) | 850 (12.6) |

| NSCLC not otherwise specified | 849 (10.2) | 1062 (15.7) |

| Lung large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 92 (1.1) | 131 (1.9) |

| Lung adenosquamous carcinoma | 90 (1.0) | 32 (0.5) |

| Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma | 53 (0.6) | 53 (0.7) |

| Lung large cell carcinoma | 21 (0.2) | 31 (0.5) |

| Pulmonary carcinosarcoma | 9 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) |

| Non-squamous NSCLC | 5942 (71.7) | 5671 (84.1) |

| TPS, % | ||

| 0 | 3513 (42.4) | 2683 (39.8) |

| 1–49 | 2416 (29.2) | 1784 (26.5) |

| ≥50 | 2356 (28.4) | 2276 (33.8) |

| Metastatic site | ||

| Lymph node | NA | 2167 (32.1) |

| Liver | NA | 765 (11.3) |

| Brain | NA | 747 (11.1) |

| Pleural fluid | NA | 520 (7.7) |

| Soft tissue | NA | 493 (7.3) |

| Bone | NA | 462 (6.9) |

| Pleura | NA | 373 (5.5) |

| Adrenal gland | NA | 231 (3.4) |

| Other | NA | 985 (14.6) |

Values in italics represent the sum of Lung adenocarcinoma, NSCLC not otherwise specified and Lung large cell carcinoma, rather than represent a different histologic subtype.

LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; NA, not applicable; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TPS, tumor proportion score.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis (dependent variable: TPS, independent variables: age, gender, primary, metastatic sites, subtypes)

| TPS <50% (reference) vs TPS ≥50% | ||||||

| Variables | All subtypes | Non-squamous NSCLC | LUSC | |||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | ||||||

| <50 years | Reference | 0.737 | Reference | 0.711 | Reference | 0.046* |

| ≥50 years | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.15) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.24) | 0.61 (0.37 to 0.99) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | Reference | 0.027* | Reference | 0.184 | Reference | 0.015* |

| Female | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.16) | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.14) | 1.23 (1.04 to 1.44) | |||

| Bx site | ||||||

| Primary | Reference | <0.001* | Reference | <0.001* | Reference | 0.197 |

| Metastatic | 1.28 (1.19 to 1.37) | 1.37 (1.27 to 1.49) | 0.89 (0.74 to 1.06) | |||

| Primary (reference) vs metastatic site | ||||||

| Lymph node | 1.58 (1.43 to 1.74) | <0.001* | 1.80 (1.61 to 2.00) | <0.001* | 0.83 (0.63 to 1.08) | 0.163 |

| Liver | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.16) | 0.835 | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.24) | 0.75 | 1.21 (0.79 to 1.87) | 0.385 |

| Brain | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.18) | 0.994 | 1.02 (0.85 to 1.21) | 0.842 | 0.96 (0.51 to 1.81) | 0.903 |

| Pleural fluid | 1.48 (1.23 to 1.78) | <0.001* | 1.53 (1.27 to 1.84) | <0.001* | 0 (0 to 3.24e+166) | 0.95 |

| Soft tissue | 1.30 (1.08 to 1.58) | 0.007* | 1.44 (1.17 to 1.79) | 0.001* | 0.92 (0.58 to 1.47) | 0.73 |

| Bone | 0.83 (0.67 to 1.04) | 0.101 | 0.81 (0.64 to 1.02) | 0.073 | 0.87 (0.45 to 1.69) | 0.684 |

| Pleura | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.40) | 0.343 | 1.14 (0.89 to 1.45) | 0.288 | 0.83 (0.39 to 1.77) | 0.628 |

| Adrenal gland | 1.70 (1.30 to 2.22) | <0.001* | 1.66 (1.24 to 2.21) | 0.001* | 2.04 (0.87 to 4.76) | 0.1 |

*p < 0.05

LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TPS, tumor proportion score.

Figure 1.

(A) Comparison of PD-L1 TPS between primary and metastatic sites; all subtypes. (B) PD-L1 TPS stratified by sampling site. (C) Comparison of PD-L1 TPS between primary and metastatic sites; non-squamous NSCLC. (D) Comparison of PD-L1 TPS between primary and metastatic sites; LUSC. LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score.

In patients with non-squamous NSCLC, metastatic lesions were more likely to have high PD-L1 expression (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.49; p<0.001) versus primary site lesions; the trend was reversed for LUSC patients (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.06; p=0.197; table 2, figure 1C, D). Furthermore, age and gender are known to alter immune surveillance8 9; there was a higher probability of women having TPS ≥50% (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.16; p=0.027) versus men; driven by the higher TPS of LUSC female patients (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.44; p=0.015; table 2). Age was statistically significant only in the LUSC subtype (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.99; p=0.046).

Discussion

In this study, we used a very large real-world lung cancer cohort, to comprehensively assess the intertumoral heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression in non-paired primary and metastatic specimens. We focused on negative or low versus high TPS values for PD-L1 expression (TPS <50% and TPS ≥50%, respectively), since this cut-off is the most reproducible among ‘real-world’ pathologists.1 7 We found high PD-L1 expression (TPS ≥50%) in 28.4% of the primary versus 33.8% of the metastatic lung cancer samples (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.37; p<0.001; tables 1 and 2). This suggests that sampling of lung cancer at a metastatic site is more likely to result in high PD-L1 expression, consistent with previous studies.2 5 6

Subsequently, we compared TPS between various metastatic sites to the primary site. We saw that samples obtained from lymph nodes, pleural fluid, soft tissue and adrenal gland were more likely to be PD-L1 high than those obtained from the primary tumor site; samples from pleura, liver, brain and bone were not.3 10 A lower or negative TPS from these sites (pleura, liver, brain and bone) could preclude otherwise eligible patients from receiving immunotherapy when metastatic site is the preferred sampling site.

Site of metastasis seems to play an important role in PD-L1 expression. Immune surveillance differs among organs and consequently alters susceptibility to cancer dissemination. Through plasticity of clonal evolution of NSCLC over time, selective metastases may occur resulting in subclones of variable tumor grade and PD-L1 expression in metastatic sites.11 A recent study in patients with NSCLC showed that PD-L1 expression in metastatic lymph nodes was not correlated with clinical outcomes.10 Interestingly, data from the FMI database on triple negative breast cancer showed that PD-L1 positivity rates were significantly higher in primary tumors rather than metastatic lesions, indicating a reverse trend from our results in lung cancer.12 However, in that study PD-L1 expression was scored on immune cells and the cut-off for positivity was 1%, precluding direct comparisons.

In addition, we observed significant deviations in PD-L1 TPS according to histologic subtype. Patients with non-squamous histology were more likely to have high TPS in metastatic rather than primary lesions (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.49; p<0.001). However, results were not significant for patients with squamous histology. Similar studies have reported subtype as an independent variable linked with PD-L1 expression but with conflicting results.10 13 14 Differences in PD-L1 protein expression between squamous and non-squamous NSCLC may extend beyond the distinct morphology of squamous tumor cells and their ability to produce keratin, that can affect IHC staining patterns. Tumor microenvironment also varies between the two subtypes, indicating differences in immunogenicity that can in part explain the observed discordances in PD-L1 expression.1 15 16 Importantly, younger (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.99; p=0.046) and female (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.44; p=0.015) patients with LUSC were more likely to have high PD-L1 TPS. A recent meta-analysis showed comparable efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 axis inhibitors in adults younger and ≥65 years of age.17 Current literature suggests differences in antigenicity between tumors from male and female patients; overall survival data from a meta-analysis in patients with lung cancer indicated that men derive a statistically significantly larger benefit from PD-1 monotherapy than women, whereas women benefit more from the addition of chemotherapy to immunotherapy.18 19

The limitations of this work include the facts that the study is retrospective, and the samples are not matched since obtaining matched samples from both primary and metastatic sites is only rarely clinically indicated. As tissue accessibility drives routine patient care, real-world studies of matched specimens may never be done. Also, due to lack of that information, we were unable to control for factors that are known to be related with PD-L1 expression, such as smoking status, stage and mutation status.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that PD-L1 TPS is significantly associated with the histologic type and with primary versus metastatic sampling sites. This work may raise awareness of this variable for future trial design and have impact on patient management.

Acknowledgments

Dr Moutafi and Dr Vathiotis were supported by a scholarship from the Hellenic Society of Medical Oncologists (HESMO).

Footnotes

Contributors: MKM, WW and WT helped in data analysis and writing. RH, JH, BA, SR and JSR helped in writing the manuscript. LP and KS performed data interpretation. IAV helped in the data analysis, concept, design, data interpretation and writing. DLR was involved in concept, design, data interpretation and writing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: RH, JH, BA, SR and JSR are employees of Foundation Medicine. DLR has served as an advisor for AstraZeneca, Agendia, Amgen, BMS, Cell Signaling Technology, Cepheid, Daiichi Sankyo, Genoptix/Novartis, GSK, Konica Minolta, Merck, NanoString, PAIGE.AI, Perkin Elmer, Roche, Ventana and Ultivue, and received research funding from AstraZeneca, Cepheid, NavigateBP, NextCure, Nanostring, Lilly and Ultivue. LP has received consulting fees and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb Genentech, Eisai, Pieris, Immunomedics, Seattle Genetics, Clovis, Syndax, H3Bio and Daiichi.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data requests may be submitted to Dr Richard SP Huang (rhuang@foundationmedicine.com) at Foundation Medicine.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Approval for this study, including a waiver of informed consent and a HIPAA waiver of authorization, was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 20152817).

References

- 1.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mansfield AS, Murphy SJ, Peikert T, et al. Heterogeneity of programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in multifocal lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:2177–82. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kluger HM, Zito CR, Barr ML, et al. Characterization of PD-L1 expression and associated T-cell infiltrates in metastatic melanoma samples from variable anatomic sites. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:3052–60. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szekely B, Bossuyt V, Li X, et al. Immunological differences between primary and metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2018;29:2232–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdy399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinato DJ, Shiner RJ, White SDT, et al. Intra-tumoral heterogeneity in the expression of programmed-death (PD) ligands in isogeneic primary and metastatic lung cancer: implications for immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1213934. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1213934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munari E, Zamboni G, Marconi M, et al. Pd-L1 expression heterogeneity in non-small cell lung cancer: evaluation of small biopsies reliability. Oncotarget 2017;8:90123–31. 10.18632/oncotarget.21485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rimm DL, Han G, Taube JM, et al. A prospective, multi-institutional, Pathologist-Based assessment of 4 immunohistochemistry assays for PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1051–8. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nikolich-Žugich J. The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system. Nat Immunol 2018;19:10–19. 10.1038/s41590-017-0006-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16:626–38. 10.1038/nri.2016.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong L, Negrao MV, Dibaj SS, et al. Programmed Death-Ligand 1 heterogeneity and its impact on benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:1449–59. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massagué J, Obenauf AC. Metastatic colonization by circulating tumour cells. Nature 2016;529:298–306. 10.1038/nature17038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozenblit M, Huang R, Danziger N, et al. Comparison of PD-L1 protein expression between primary tumors and metastatic lesions in triple negative breast cancers. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001558. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun J-M, Zhou W, Choi Y-L, et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a large cohort study of surgically resected cases. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1003–11. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoenfeld AJ, Rizvi H, Bandlamudi C, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of PD-L1 expression in patients with lung adenocarcinomas. Ann Oncol 2020;31:599–608. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.01.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou C, Tang J, Sun H, et al. Pd-L1 expression as poor prognostic factor in patients with non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8:58457–68. 10.18632/oncotarget.17022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng X, Gao Y, Yang L, et al. Immune microenvironment differences between squamous and non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer and their influence on the prognosis. Clin Lung Cancer 2019;20:48–58. 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias R, Giobbie-Hurder A, McCleary NJ, et al. Efficacy of PD-1 & PD-L1 inhibitors in older adults: a meta-analysis. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:26. 10.1186/s40425-018-0336-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S, Cowley LA, Liu X-S. Sex differences in cancer immunotherapy efficacy, biomarkers, and therapeutic strategy. Molecules 2019;24. 10.3390/molecules24183214. [Epub ahead of print: 04 Sep 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conforti F, Pala L, Bagnardi V, et al. Sex-Based heterogeneity in response to lung cancer immunotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:772–81. 10.1093/jnci/djz094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data requests may be submitted to Dr Richard SP Huang (rhuang@foundationmedicine.com) at Foundation Medicine.