Abstract

Context

COVID-19 has had an unprecedent impact on physicians, nurses and other health professionals around the world, and a serious healthcare burnout crisis is emerging as a result of this pandemic.

Objectives

We aim to identify the causes of occupational stress and burnout in women in medicine, nursing and other health professions during the COVID-19 pandemic and interventions that can support female health professionals deal with this crisis through a rapid review.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and ERIC from December 2019 to 30 September 2020. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO and is available online. We selected all empirical studies that discussed stress and burnout in women healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

The literature search identified 6148 citations. A review of abstracts led to the retrieval of 721 full-text articles for assessment, of which 47 articles were included for review. Our findings show that concerns of safety (65%), staff and resource adequacy (43%), workload and compensation (37%) and job roles and security (41%) appeared as common triggers of stress in the literature.

Conclusions and relevance

The current literature primarily focuses on self-focused initiatives such as wellness activities, coping strategies, reliance of family, friends and work colleagues to organisational-led initiatives such as access to psychological support and training. Very limited evidence exists about the organisational interventions such as work modification, financial security and systems improvement.

Keywords: health services administration & management, health & safety, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This rapid review included 47 studies representing 18 668 women in healthcare.

This study used Bolman and Deal’s (2017) four-frame leadership model to explain the contextual factors of stress and burnout experienced by women health professionals.

This study used the WHO guidelines on rapid reviews and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines to guide this rapid review.

Quality of evidence was assessed using the Quality Rating Scheme for Studies and Other Evidence.

Due to the heterogeneity of data collected in the included studies, a meta-analysis was not appropriate.

Introduction

The health sector is facing an unprecedented burden due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at the frontline providing essential services, and they are experiencing increased harassment, stigmatisation, physical violence and psychological trauma, including increased rates of burnout, depression, anxiety, substance abuse and suicide due to COVID-19.1–4 Amnesty International has recorded the deaths of over 7000 health workers worldwide due to COVID-19. In the USA alone, over 250 000 health workers have been infected, and nearly 1000 deaths have occurred.5 6

Women in healthcare experience specific challenges with adapting to COVID-19 related public health measures, in addition to the pre-existing systemic challenges related to workplace gender bias, discrimination, sexual harassment and inequities.7 The pandemic has taken a disproportionate toll on women in the workplace.8 Women make up 75% of HCWs globally.9 Female physicians are already more likely than male physicians to experience depression, burnout and suicidal ideation.10 11 On average, women performed 2.5 times of unpaid work per day compared with men as parents and primary caregivers to family members.12

In this review, we explore factors that may influence stress and burnout in women health professionals and describe how different type of intervention organisations can offer to support women health professionals.

Methods

Overall objectives

The overall objectives of this review are to: (A) explore the triggers of occupational stress and burnout faced by women in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic and (B) identify interventions that can support their well-being through a systematic review.

Materials and methods

We conducted a rapid review in accordance with the WHO Rapid Review Guide13 and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO and is available online (CRD42020189750).

Ethical considerations

This study used secondary data analysis using published research; therefore, it did not require submission to the research ethics committee.

Theoretical model

The WHO classified burnout and occupation stress as an occupational phenomenon.14 In this context, we used Bolman and Deal’s (2017) four-frame model of leadership to understand the stress and burnout experienced by women health professionals.15 The four-frame model provides an approach to describe organisational issues through four perspectives: structural, human resource, symbolic and political. The structural frame focuses on rules, roles, strategy, policies, technology and work environment. The human resource frame considers individual needs, skills and relationships. The political frame examines power, conflict, competition and organisational politics, and the symbolic frame includes culture, meaning, rituals and stories.

Research questions

The following research questions guided the rapid review: what are the triggers of stress and burnout in women in healthcare? What interventions are effective in preventing occupational stress and burnout?

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria are included in table 1. First, we were only interested in articles published from December 2019 to 30 September 2020 (the last day of the literature search). We chose this timeframe to include research related to experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study specifically focused on the experiences of women in healthcare, encompassing a broad array of health professionals including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, midwives, paramedics, physical therapists, technicians, personnel support workers and community health workers. We only included articles that focused primarily on women in healthcare or that provided a breakdown of data according to sex/gender. Given the transboundary nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, we included articles published globally. We defined occupational stress as the degree to which one feels overwhelmed and unable to cope as a result of unmanageable work-related pressures, and we defined burnout as the experience of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation or cynicism, along with feelings of diminished personal efficacy or accomplishment in the context of the work environment.16 We included primary where data were collected and analysed using objective quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods. We excluded editorials and opinion pieces.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Authors (last name of first author) | Year | Evidence source | Country | Research design | Health professionals | Sample size | Female participants (%) | ||

| Physicians | Nurses | Other | |||||||

| Algunmeeyn | 2020 | 20 | Jordan | Qualitative | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 30 | 23 |

| Alsulais | 2020 | 21 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 529 | 40 | ||

| Cai | 2020 | 22 | China | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 534 | 69 |

| De Stefani | 2020 | 23 | Italy | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 1500 | 56 | ||

| Elbay | 2020 | 24 | Turkey | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 442 | 57 | ||

| Fargen | 2020 | 25 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 151 | 14 | ||

| Gao | 2020 | 26 | China | Qualitative | ✓ | 14 | 93 | ||

| Hoffman | 2020 | 27 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 365 | 69 |

| Kackin | 2020 | 28 | Turkey | Qualitative | ✓ | 10 | 80 | ||

| Kang | 2020 | 29 | China | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 994 | 86 | |

| Karimi | 2020 | 30 | Iran | Qualitative | ✓ | 12 | 67 | ||

| Khalafallah | 2020 | 31 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 407 | 11 | ||

| Lai | 2020 | 32 | China | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 1257 | 77 | |

| Li | 2020 | 33 | China | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4369 | 100 |

| Liu | 2020 | 34 | China | Qualitative | ✓ | ✓ | 13 | 62 | |

| Martinez-Lopez | 2020 | 35 | Spain | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 157 | 79 | |

| Moorthy | 2020 | 36 | UK | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 200 | 50 | |

| Mosheva | 2020 | 37 | Israel | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 1106 | 49 | ||

| Ng | 2020 | 38 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 22 | 77 | |

| Nowicki | 2020 | 39 | Poland | Qualitative | ✓ | 325 | 96 | ||

| Nyashanu | 2020 | 40 | UK | Qualitative | ✓ | ✓ | 40 | 53 | |

| Osama | 2020 | 41 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 112 | 40 | ||

| Prasad | 2020 | 42 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 347 | 91 | |

| Rabbani | 2020 | 43 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 398 | 40 |

| Rodriguez | 2020 | 44 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 426 | 45 | ||

| Ruiz-Fernandez | 2020 | 45 | Spain | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 506 | 77 | |

| Rymarowicz | 2020 | 46 | Poland | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 304 | 31 | |

| Sandesh | 2020 | 47 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 112 | 43 | ||

| Shah | 2020 | 48 | UK | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 207 | 81 | ||

| Shalhub | 2020 | 49 | International | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 1609 | 29 | ||

| Sharma | 2020 | 50 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1651 | 74 |

| Shechter | 2020 | 51 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 657 | 77 |

| Si | 2020 | 52 | China | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 863 | 71 |

| Sil | 2020 | 53 | India | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 23 | 70 | |

| Silczuk | 2020 | 54 | Poland | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 117 | 53 | ||

| Smith | 2020 | 55 | Canada | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 5988 | 91 | ||

| Spiller | 2020 | 56 | Switzerland | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 812 | 71 | |

| Stojanov | 2020 | 57 | Serbia | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 201 | 65 | |

| Suryavanshi | 2020 | 58 | India | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | 197 | 51 | |

| Tan | 2020 | 59 | China | Qualitative | ✓ | 30 | 80 | ||

| Temsah | 2020 | 60 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 582 | 75 |

| Thomaier | 2020 | 61 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 374 | 63 | ||

| Tsan | 2020 | 62 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 85 | 64 | ||

| Uvais | 2020 | 63 | India | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 58 | 40 | ||

| Xiao | 2020 | 64 | China | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 958 | 67 |

| Zhang | 2020 a | 65 | Iran | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | 304 | 59 | ||

| Zhang | 2020b | 66 | Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia | Cross-sectional survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 712 | 68 |

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Search methods and information sources

We conducted comprehensive literature search strategies in the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (via Ovid), Embase (via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (via Ovid) and ERIC (via ProQuest). We developed our search strategies via an academic health sciences librarian with input from the research team. The search was originally built in MEDLINE Ovid and peer-reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies tool.17 We limited our searches to articles published in English no later than 30 September 2020. The final search results were exported into Covidence, review management software, where duplicates were identified and removed.

Screening process

To minimise selection bias, we piloted 20 citations against a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria. After high agreement was achieved, two reviewers independently screened all citations. Conflicts were resolved by discussion or via a third reviewer. The same process was used for full-text screening of potentially eligible studies.

Rating of the quality of evidence

The strength of data and subsequent recommendations for interventions were graded according to the Quality Rating Scheme for Studies and Other Evidence by two reviewers independently, with discrepancies resolved after joint review and discussion.18

Data extraction

We used a predefined data extraction form to extract data from the papers included in the rapid review. To ensure the integrity of the assessment, we piloted the data extraction form on three studies. We extracted the following information from the studies: the first author, year of publication, health professionals enrolled in the study, geographic location, study methods, quality of evidence, triggers of stress and burnout, interventions and outcomes.

Data synthesis

Due to heterogeneity of data collected in the included studies, meta-analysis was not appropriate. Instead, we thematically synthesised the data using the thematic analysis process described in Clarke et al (2012) and grouped the triggers using Bolman and Deal’s (1991) four frame model of leadership.19

Results

Search results

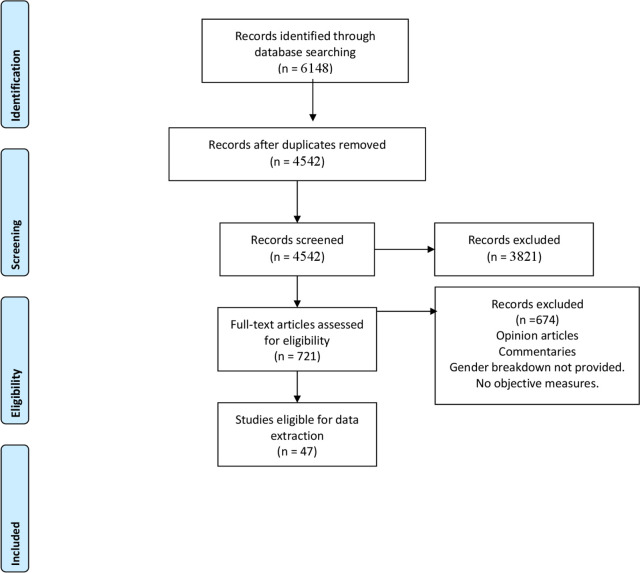

The literature search resulted in a total of 6148 records. After 1606 duplicates were removed, 4542 records remained to be screened. We assessed 721 full-text articles and found 47 published studies with 18 668 female health workers met our inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flowchart presents the selection of publications (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article selection for further review and scoring.

Characteristics of studies

Our search identified 47 eligible studies. Of these, 39 (83%) were cross-sectional studies and eight (17%) were qualitative studies. Studies came from Asia (34%), Europe (27.6%), Middle East (14.9%), North America (19.1%) and Latin America (2%) (see table 1). These studies focused on physicians (74%), nurses (57%) and other health professionals (45%; including dentists, personal support workers, pharmacists and administrative professionals). The study samples often included both male and women health professionals; however, these studies also provided gender-based breakdowns. In all, 62% of the total 29 398 study population focused on female health professionals.

Triggers of stress and burnout faced by women in healthcare

Triggers of stress and burnout were grouped using the Bolman and Deal’s (2017) four-frame model of leadership (table 2).

Table 2.

Triggers of stress and burnout during COVID-19

| Author | Year | Evidence source | Triggers | |||||||||||||

| Structural | Human resources | Symbolic | Political | |||||||||||||

| Staff and resource adequacy | Workload and compensation | Job roles and job security | Female gender | Age/family status | Safety | Experience | Patient care protocols | Societal expectations | Organisation culture | Public health guidance | Infrastructure | Pandemic preparedness | Social isolation | |||

| Algunmeeyn | 2020 | 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| AlSulais | 2020 | 21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cai | 2020 | 22 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| DeStefani | 2020 | 23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Elbay | 2020 | 24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Fargen | 2020 | 25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Gao | 2020 | 26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Hoffman | 2020 | 27 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Kackin | 2020 | 28 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kang | 2020 | 29 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Karimi | 2020 | 30 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Khalafallah | 2020 | 31 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Lai | 2020 | 32 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Li | 2020 | 33 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Liu | 2020 | 34 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Martinez-Lopez | 2020 | 35 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Matthewson | 2020 | 36 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Moorthy | 2020 | 37 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Mosheva | 2020 | 38 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Hau Ng | 2020 | 39 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Nowicki | 2020 | 40 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Nyashanu | 2020 | 41 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Osama | 2020 | 42 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Prasad | 2020 | 43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Rabbani | 2020 | 44 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Rodriguez | 2020 | 45 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Rymarowicz | 2020 | 46 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Sandesh | 2020 | 47 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Shah | 2020 | 48 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Shalhub | 2020 | 49 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sharma | 2020 | 50 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Shechter | 2020 | 51 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Si | 2020 | 52 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Sil | 2020 | 53 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Silczuk | 2020 | 54 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Smith | 2020 | 55 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Spiller | 2020 | 56 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Stojanov | 2020 | 57 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Suryavanshi | 2020 | 58 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Tan | 2020 | 59 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Temsah | 2020 | 60 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Thomaier | 2020 | 61 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Tsan | 2020 | 62 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Uvais | 2020 | 63 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Xiao | 2020 | 64 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Zhang | 2020a | 65 | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Zhang | 2020b | 66 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

Primary forces of stress and burnout in women in healthcare during COVID-19 were related to structural factors (ie, organisational resources, work-related policies and roles).20–53 Resource adequacy (43%), related to lack of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and staffing shortages, was discussed as a major driver of stress and burnout in the included studies. Stress and burnout intensity differed between health professionals who had indirect patient care and direct clinical care of patients with COVID-19. A total of 43% of the studies reported that caring for patients with COVID-19 increased stress and burnout; 38% of the studies reported HCWs faced an increased workload due increased number of patients with COVID-19 under their care, and they were not appropriately compensated for the workload.

Human resource perspective primarily focuses on individual-related factors.20–27 29–31 34–45 47–50 52–65 Safety concerns and fears of getting infected with COVID-19 and putting family members at risk (66%) appeared to be the primary causes of stress and burnout. Female gender (34%) and age and family status (19%) also emerged as determinants of risk of stress and burnout. Specifically, being young with no family or being a mother with young children influenced emotional stress and burnout in women. Similarly, less work experience and self-perception about lack of competency to care for patients with COVID-19 was associated with increased prevalence of stress and burnout (26%).

In terms of the symbolic frame, concerns about organisational culture (26%), patient care protocols (17%) and societal experiences of health professionals (26%) emerged as common triggers of stress.22 26 27 30 34–36 39–42 47 50 54 63 64 66 More specifically, issues related to ambiguous patient care protocols and perceived lack of infection control guidelines influenced stress and burnout. Similarly, the organisational culture, including lack of support and recognition by peers, supervisors and hospital leadership, were triggers of stress and burnout in women health professionals. From a macrocultural perspective, the societal and media portrayal of HCWs as ‘heroes’ increased moral responsibility and caused increased stress to meet these expectations, yet health professionals faced increased social isolation and stigma as they were considered as contagious by the general population.

From the political perspective, public health measures influenced stress and burnout.21–23 26 27 33 35 43 47 64 The government-level social distancing protocols increased social isolation (15%). Furthermore, lack of pandemic preparedness (2%), poor public health guidance on screening and treatment (4%) and measures related to infrastructure such as delayed testing and lack of treatment for COVID-19 patients (4%) exacerbated to stress and burnout in women HCWs.

Interventions that can support the well-being of women HCWs during a pandemic

Only 38.3% studies have examined potential interventions to support women in healthcare with COVID-19 related stress and burnout. We grouped the interventions on a spectrum ranging from self-focused intervention to systems-focused interventions (see table 3). A percentage of 29.7 included studies primarily focused on addressing well-being and resiliency at the individual level. The current literature discussed self-initiated interventions such as regular exercise, wellness activities such as yoga and meditation, faith-based activities, self-help resources, hobbies, psychological services such as therapists, hotlines and talk therapy as treatment strategies and other adaptive coping mechanisms as useful preventative strategies for women. From a structural perspective, 21.5% of included studies recommended systems-level interventions such as work modifications, ensuring clear communication about policies, providing access to PPE, offering training related to managing COVID-19, instituting measures to support health professionals financially, providing rest areas for sleep and recovery, offering basic physical needs such as food and including training programmes to improve resiliency were considered potential strategies to support women in healthcare during the pandemic.

Table 3.

Interventions to support stress and burnout

| Intervention spectrum | Intervention type |

Example | Evidence source | Quality of evidence strength |

| Self-focused | Self-coping | Normalisation techniques | 26 50 |

Very Weak Evidence |

| Recovery and resiliency | Yoga and meditation Relaxation techniques Proper nutrition Time off Rest |

32 46 49 56 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Physical activities | Sports Exercise |

26 49 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Hobbies | Sports, cooking, movies and music Reading |

26 32 56 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Faith-based activities | Religion | 47 49 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Social networks | Family Friends Work colleagues Virtual networks |

20 32 37 46 47 50 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Psychological support | Psychologists Psychiatrist Group counselling Talk therapy |

20 24 26 27 42 46 49 55 56 57 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Systems focused | Training | PPE use SARS-CoV-2 virus Patient care protocols Resiliency |

20 24 44 53 56 |

Very Weak Evidence |

| Communication | Transparent communication between management and frontline | 24 42 47 64 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Workplace resources | Access to proper PPE Work coverage Isolation units Places for rest and sleep Childcare |

20 42 47 53 56 64 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Workplace incentives |

Flexible work policies Compensation |

20 24 25 26 42 56 |

Very Weak Evidence | |

| Process improvement | Rapid testing for patients Improved infection control protocols |

42 53 |

Very Weak Evidence |

PPE, personal protective equipment.

However, these studies did not provide evidence on the effectiveness and utility of these interventions in helping women in healthcare. There was, however, emerging evidence on the use of maladaptive coping mechanisms such as avoidant coping and substance use.25 39 44

Discussion

In this rapid review, we examined the triggering factors of occupational stress and burnout in women in healthcare in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and potential interventions to mitigate these factors. We provided an overview of the evidence and identification of potential variables that influence the mental health well-being of women in healthcare. The current research literature primarily focuses on prevalence of stress, burnout, depression and anxiety using a cross-sectional approach to show the presence of these elements at a particular point in time. Furthermore, it looks at burnout as an individual issue that can be mitigated by self-help solutions such as coping, yoga, mindfulness and practising resilience. However, very weak evidence exists on the effectiveness of these interventions on women in healthcare (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Triggers of stress and burnout.

In healthcare, there is limited understanding about burnout as an occupational phenomenon.67 First, there is a gap in the literature regarding how organisations can shape the structures, cultures and processes to address the elements that trigger stress and burnout. Similarly, there is a limited understanding of how race, culture, leadership and profession impact occupational stress and burnout during COVID-19. For example, one in three nurses who have died of COVID-19 in the USA are from the Filipino community.68 Similarly, there is a lack of understanding of burnout by occupation type. Physician burnout has received a lot of attention over the past decade, but very limited evidence exists regarding the burnout experienced by other health professionals, including support staff such as personal support workers who are at the frontlines of caring for patients in long-term care and nursing homes.

Similarly, there is very little evidence on how political factors such as policies and public health measures influence individual level burnout. For example, the US Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which required employers to provide up to 80 hours of paid sick leave for reasons related to COVID-19, allowed a provision to exclude HCWs from these benefits. A scan of social media discussions of this showed a significant stress and anxiety among HCWs. Future studies should move beyond cross-sectional studies and explore the contexts, factors, organisational and systems variables and mechanisms that influence stress and burnout variables to better understand the determinants of stress and burnout in women.

Furthermore, there is very limited evidence on the impact of stress and burnout on quality of care, patient safety, employee engagement and staff attrition and absenteeism during COVID-19. Future studies on stress and burnout among HCWs should look at the short-term, medium-term and long-term impact to healthcare systems. Specifically, research is needed to understand how COVID-19 will affect women health professional’s decisions about work.

There are several strengths to the current rapid review. To our knowledge, this is the first review that attempted to look at stress and burnout experienced by women in healthcare as an occupation phenomenon and that explored common triggers of stress and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our rapid review was guided by the Boleman and Deal’s four-frame theoretical organisational theoretical framework to understand the contextual factors through the lens of structural, human resources, politics and symbolism. Our methodology was guided by the WHO guidelines on rapid reviews and reported using the PRISMA guidelines. The studies included in the review represent a global perspective of the issues. We highlighted the important gap in current understanding related to occupational stress and burnout in women in healthcare.

The current literature on stress and burnout related to COVID-19 includes both male and female health professionals. Although the studies included in this review provided gender breakdowns in the sample framework and discussed gender-related factors, it lacked gender-based subgroup analysis of what interventions are specifically effective for women in healthcare.

Our study has some limitations due to the methodological limitations of the included studies’ characteristics: (1) we found variability in the measurement instruments; (2) studies primarily reported cross-sectional information of stress and burnout at a specific point of the pandemic; (3) studies lacked reporting on the structural, political and cultural context of stress and burnout; and (4) interventions to address stress and burnout were under-reported.

There is a significant data gap on the impact of COVID-19 on women in healthcare. We recommend that national health professional organisations develop comprehensive data gathering and monitoring strategies to improve the science of health professional burnout research.

Conclusion

Organisational leaders and research scholars should consider occupational stress and burnout as an organisational phenomenon and provide organisational-level support for HCWs. To improve occupational wellness for women in healthcare, organisations should attempt to engage their healthcare workforce to listen to their concerns, consider the specific context of the workforce and design targeted interventions based on their identified needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution by Hilary Pang, Ana Patricia Ayala, Dongjoo Lee and Sabine Caleja, who helped with article retrieval, screening and extracting data.

Footnotes

Twitter: @SriharanAbi

Contributors: All authors conceptualised and designed the review. AS and SR reviewed titles, abstracts and full-text papers for eligibility. AS and SR extracted data, and all data extraction was verified by AS prepared the initial draft manuscript. SR, ACT and DL reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported through a grant from the Canadian Institute for Health Research Operating Grant: Knowledge Synthesis: COVID-19 in Mental Health & Substance Use. ACT is funded by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Availability of data and materials: this review is registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/y8fdh/?view_only=1d943ec3ddbd4f5c8f6a9290eca2ece7).

References

- 1.Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:782. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mock J. Psychological trauma is the next crisis for coronavirus health workers. scientific American, 2020. Available: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/psychological-trauma-is-the-next-crisis-for-coronavirus-health-workers

- 3.Orr C. “COVID-19 kills in many ways”: The suicide crisis facing health-care workers. Canada’s National Observer, 2020. Available: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2020/04/29/analysis/covid-19-kills-many-ways-suicide-crisis-facing-health-care-workers

- 4.Roycroft M, Wilkes D, Fleming S, et al. Preventing psychological injury during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020;369:m1702. 10.1136/bmj.m1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amnesty International . Global: amnesty analysis reveals over 7,000 health workers have died from COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/09/amnesty-analysis-7000-health-workers-have-died-from-covid19

- 6.CDC . Cases & deaths among healthcare personnel. Available: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#health-care-personnel

- 7.Ghebreyesus T. Female health workers drive global health, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/female-health-workers-drive-global-healthMarch2019

- 8.Brubaker L. Women physicians and the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;324:835–6. 10.1001/jama.2020.14797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Gender and health workforce statistics. Geneva: Human Resources for Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold KJ, Andrew LB, Goldman EB, et al. "I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record": A survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016;43:51–7. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guille C, Frank E, Zhao Z, et al. Work-family conflict and the sex difference in depression among training physicians. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1766–72. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, et al. Gender-Based differences in burnout: issues faced by women physicians. NAM Perspectives 2019. 10.31478/201905a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UN Women . Redistribute unpaid work. Available: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/redistribute-unpaid-work [Accessed Dec 6 2020].

- 14.Tricco AC, Langlois EV, Straus SE. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: A practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 11th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolman LG, Deal TE. Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership. John Wiley & Sons, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;75:40–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.JAMA . Quality rating scheme for studies and other evidence. Available: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/pages/instructions-for-authors#SecRatingsofQuality

- 19.Clarke V, Braun V, Hayfield N. "Thematic analysis." Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods 2015:222–48.

- 20.Algunmeeyn A, El-Dahiyat F, Altakhineh MM, et al. Understanding the factors influencing healthcare providers’ burnout during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Jordanian hospitals. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 2020;13:p53. 10.1186/s40545-020-00262-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai H, Tu B, Ma J. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Medical Science Monitor;2020:e924171–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Stefani A, Bruno G, Mutinelli S, et al. COVID-19 outbreak perception in Italian dentists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020;2020;17:3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacıoğlu S, et al. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Research 2020;113130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fargen KM, Leslie-Mazwi TM, Klucznik RP, et al. The professional and personal impact of the coronavirus pandemic on us neurointerventional practices: a nationwide survey. J Neurointerv Surg 2020;12:927–31. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao X, Jiang L, Hu Y, et al. Nurses’ experiences regarding shift patterns in isolation wards during the COVID‐19 pandemic in China: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2020;29:4270–80. 10.1111/jocn.15464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kackin O, Ciydem E, Aci OS, et al. Experiences and psychosocial problems of nurses caring for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in turkey: a qualitative study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2020;2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karimi Z, Fereidouni Z, Behnammoghadam M, et al. The Lived Experience of Nurses Caring for Patients with COVID-19 in Iran: A Phenomenological Study]]>. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2020;13:1271–8. 10.2147/RMHP.S258785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalafallah AM, Lam S, Gami A, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among attending neurosurgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020;198:106193. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu C-Y, Yang Y-zhi, Zhang X-M, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors for anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. SSRN Journal 2020:1–17. 10.2139/ssrn.3548781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.JÁ M-L, Lázaro-Pérez C, Gómez-Galán J, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 emergency on health professionals: Burnout incidence at the most critical period in Spain. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020;9:3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moorthy A, Sankar TK. Emerging public health challenge in UK: perception and belief on increased COVID19 death among BamE healthcare workers. J Public Health 2020;42:486–92. 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosheva M, Hertz-Palmor N, Dorman Ilan S, et al. Anxiety, pandemic-related stress and resilience among physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety 2020;37:965–71. 10.1002/da.23085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nowicki GJ, Ślusarska B, Tucholska K, et al. The severity of traumatic stress associated with COVID-19 pandemic, perception of support, sense of security, and sense of meaning in life among nurses: research protocol and preliminary results from Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:6491. 10.3390/ijerph17186491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osama M, Zaheer F, Saeed H, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on surgical residency programs in Pakistan; A residents’ perspective. Do programs need formal restructuring to adjust with the “new normal”? A cross-sectional survey study. International Journal of Surgery 2020;79:252–6. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabbani U, Al Saigul AM. Knowledge, attitude and practices of health care workers about corona virus disease 2019 in Saudi Arabia. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2020;11:60. 10.2991/jegh.k.200819.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez RM, Medak AJ, Baumann BM, et al. Academic Emergency Medicine Physicians’ Anxiety Levels, Stressors, and Potential Stress Mitigation Measures During the Acceleration Phase of the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Academic Emergency Medicine 2020;27:700–7. 10.1111/acem.14065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz‐Fernández MD, Ramos‐Pichardo JD, Ibáñez‐Masero O, et al. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID‐19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs 2020;29:4321–30. 10.1111/jocn.15469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandesh R, Shahid W, Dev K, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare professionals in Pakistan. Cureus 2020;27. 10.7759/cureus.8974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah N, Raheem A, Sideris M, et al. Mental health amongst obstetrics and gynaecology doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of a UK-wide study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;253:90–4. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shalhub S, Mouawad NJ, Malgor RD. Global vascular surgeons’ experience, stressors, and coping during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2020;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma M, Creutzfeldt CJ, Lewis A, et al. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of critical care resource availability and factors associated with mental well-being during COVID-19: Results from a US survey. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shechter A, Diaz F, Moise N. New York health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. General Hospital Psychiatry 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MY S, XY S, Jiang Y. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty 2020;2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith PM, Oudyk J, Potter G, et al. The association between the perceived adequacy of workplace infection control procedures and personal protective equipment with mental health symptoms: a cross-sectional survey of Canadian health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spiller TR, Méan M, Ernst J, et al. Development of health care workers’ mental health during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Switzerland: two cross-sectional studies. Psychol Med 2020;42:1–4. 10.1017/S0033291720003128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suryavanshi N, Kadam A, Dhumal G, et al. Mental health and quality of life among healthcare professionals during the COVID‐19 pandemic in India. Brain Behav 2020;10. 10.1002/brb3.1837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan R, Yu T, Luo K. Experiences of clinical first‐line nurses treating patients with COVID‐19: a qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management 2020;28:1381–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Temsah MH, Alhuzaimi AN, Alamro N, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of healthcare workers during the early COVID-19 pandemic in a main, academic tertiary care centre in Saudi Arabia. Epidemiol Infect 2020;148:e203. 10.1017/S0950268820001958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomaier L, Teoh D, Jewett P. Emotional health concerns of oncology physicians in the United States: fallout during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsan SEH, Kamalanathan A, Lee CK, et al. A survey on burnout and depression risk among anaesthetists during COVID‐19: the tip of an iceberg? Anaesthesia 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao X, et al. Psychological impact of health care workers in China during COVID-19 pneumonia epidemic: a multi-center cross-sectional survey investigation. Journal of Affective Disorders 2020;2020:405–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang SX, Sun S, Afshar Jahanshahi A, et al. Developing and testing a measure of COVID-19 organizational support of healthcare workers - results from Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia. Psychiatry Res 2020;291:113174. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al Sulais E, Mosli M, AlAmeel T. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2020;26:249. 10.4103/sjg.SJG_174_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:11–17. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li G, Miao J, Wang H, et al. Psychological impact on women health workers involved in COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan: a cross-sectional study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020;91:895–7. 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.BH N, Nuratiqah NA, Faisal AH. A descriptive study of the psychological experience of health care workers in close contact with a person with COVID-19. The Medical Journal of Malaysia 2020;75:485–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nyashanu M, Pfende F, Ekpenyong M. Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J Interprof Care 2020;34:655–61. 10.1080/13561820.2020.1792425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prasad A, Civantos AM, Byrnes Y, et al. Snapshot impact of COVID-19 on mental wellness in nonphysician otolaryngology health care workers: a national study. OTO Open 2020;4:2473974X2094883. 10.1177/2473974X20948835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rymarowicz J, Stefura T, Major P. General surgeons’ attitudes towards COVID-19: A national survey during the SARS-CoV-2 virus outbreak. European Surgery 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sil A, Das A, Jaiswal S. Mental health assessment of frontline COVID‐19 dermatologists: a pan-Indian multicentric cross‐sectional study. Dermatologic Therapy 2020;2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Silczuk A. Threatening increase in alcohol consumption in physicians quarantined due to coronavirus outbreak in Poland: the ALCOVID survey. J Public Health 2020;42:461–5. 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stojanov J, Malobabic M, Stanojevic G, et al. Quality of sleep and health-related quality of life among health care professionals treating patients with coronavirus disease-19. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2020:002076402094280. 10.1177/0020764020942800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uvais NA, Shihabudheen P, Hafi NAB. Perceived stress and stigma among doctors working in COVID-19–Designated hospitals in India. The Primary Care Companion For CNS Disorders 2020;22:20br02724. 10.4088/PCC.20br02724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang SX, Liu J, Jahanshahi AA. At the height of the storm: Healthcare staff’s health conditions and job satisfaction and their associated predictors during the epidemic peak of COVID-19. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoffman KE, Garner D, Koong AC, et al. Understanding the intersection of working from home and burnout to optimize post-COVID19 work arrangements in radiation oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;108:370–3. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.06.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020;323:2133–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.5893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shoichet . Covid-19 is taking a devastating toll on Filipino American nurses, 2020. Available: https://www.cnn.com/2020/11/24/health/filipino-nurse-deaths/index.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Availability of data and materials: this review is registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/y8fdh/?view_only=1d943ec3ddbd4f5c8f6a9290eca2ece7).