Abstract

Introduction

The acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a highly relevant entity in critical care with mortality rates of 40%. Despite extensive scientific efforts, outcome-relevant therapeutic measures are still insufficiently practised at the bedside. Thus, there is a clear need to adhere to early diagnosis and sufficient therapy in ARDS, assuring lower mortality and multiple organ failure.

Methods and analysis

In this quality improvement strategy (QIS), a decision support system as a mobile application (ASIC app), which uses available clinical real-time data, is implemented to support physicians in timely diagnosis and improvement of adherence to established guidelines in the treatment of ARDS. ASIC is conducted on 31 intensive care units (ICUs) at 8 German university hospitals. It is designed as a multicentre stepped-wedge cluster randomised QIS. ICUs are combined into 12 clusters which are randomised in 12 steps. After preparation (18 months) and a control phase of 8 months for all clusters, the first cluster enters a roll-in phase (3 months) that is followed by the actual QIS phase. The remaining clusters follow in month wise steps. The coprimary key performance indicators (KPIs) consist of the ARDS diagnostic rate and guideline adherence regarding lung-protective ventilation. Secondary KPIs include the prevalence of organ dysfunction within 28 days after diagnosis or ICU discharge, the treatment duration on ICU and the hospital mortality. Furthermore, the user acceptance and usability of new technologies in medicine are examined. To show improvements in healthcare of patients with ARDS, differences in primary and secondary KPIs between control phase and QIS will be tested.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the independent Ethics Committee (EC) at the RWTH Aachen Faculty of Medicine (local EC reference number: EK 102/19) and the respective data protection officer in March 2019. The results of the ASIC QIS will be presented at conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

DRKS00014330.

Keywords: adult intensive & critical care, information technology, health informatics, respiratory medicine (see thoracic medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Continuous monitoring of routinely collected parameters to improve the timely diagnosis in acute respiratory distress syndrome, especially of frequently underdiagnosed mild stages as well as to increase guideline adherent therapy.

Usage of mobile devices on intensive care units to shorten response time onto clinically relevant events in critical care medicine.

Realisation of interoperability of heterogeneous medical routine data to improve its use for research and improvement of care and to enable cross-site data exchange.

No mandatory changes in clinical care, as treatment remains in the full responsibility of the physician in charge.

Statistic analysis will not comply with the standards of a regular clinical trial, since a quality improvement strategy was chosen to prove feasibility and means of implementation.

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening medical condition associated with mortality rates ranging approximately from 25% to 46% across all severities and can be even higher when associated with dysfunction of other organs.1 2 Depending on the severity of hypoxia which is defined by the arterial oxygen tension (paO2)/fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio (Horovitz quotient), moderate ARDS (with a paO2/FiO2 ratio 101–200) has been reported to occur in 16–23 and severe ARDS (with a paO2/FiO2 ratio ≤100) in 58–79 per 100 000 inhabitants per year.3 Lung-protective ventilation, that is, the use of low tidal volumes and the limitation of airway pressures, has been shown to improve outcomes compared with mechanical ventilation with high tidal volumes and airway pressures. Despite this outcome-improving strategy, the large multicentre, observational ‘LUNG SAFE’-trial observed a low adherence to lung-protective ventilatory strategies and guidelines associated with a high mortality rate up to 46% in severe ARDS.1 An additional finding of the LUNG SAFE-trial was that up to 39% of the ARDS cases were not diagnosed by the physicians, which suggests procedural and infrastructural deficits. Particularly early and mild or moderate ARDS often remains unrecognised until respiratory dysfunction of the patient has deteriorated further and severe hypoxia is present. By implementing consistent lung-protective ventilation, as described in the German guideline ‘Invasive ventilation and use of extracorporeal procedures in acute respiratory insufficiency’,4 significant improvement in the prognosis of this disease entity should be achieved.5 6 However, implementation of these therapy principles cannot be achieved when ARDS is not or not early enough diagnosed. Hence, improvements in both ARDS screening as well as in implementation of evidence-based therapeutic measures are urgently needed. Improvements of procedural and infrastructural deficits might be provided by intelligent technical solutions.7 8 A software approach preprocessing data from electronic health records (EHRs) and providing diagnostic data and treatment recommendations on a mobile device might be such a solution. This approach has been taken by the use case ‘Algorithmic Surveillance of intensive care unit (ICU) patients with ARDS’ (ASIC). ASIC is an integral part of the ‘Smart Medical Information Technology for Healthcare’ (SMITH) project.9 SMITH is one of four consortia funded by the ‘Medical Informatics Initiative’ of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.10

The objective of our quality improvement project is to improve ARDS detection and guideline adherence in the treatment of mechanically ventilated ARDS-patients by implementing an application software (app) provided on a mobile device and consecutively improve outcome in this patient population.

Methods and analysis

ASIC app

The ASIC app is a mobile, technical support system to facilitate diagnosis and therapy of ARDS and has been specifically developed for this project. It operates system independently on different devices. As part of the ASIC project, it is intended to be used on a mobile device (eg, tablet, smartphone). The data used by the ASIC app are obtained from the local EHR. According to these data, a diagnosis of ARDS can be made by the physician according to the Berlin Criteria.11 Manual entries are required for the findings, which are not documented automatically, like radiographic reports. Due to these functions, the ASIC app only displays a compilation of already existing and documented clinical routine data.

ARDS is suspected in mechanically ventilated patients (≥24 hours duration) by automated ASIC app dependent positive screening of respiratory dysfunction. The duration of mechanical ventilation, the paO2/FiO2 ratio and the positive endexpiratory pressure (PEEP) are extracted and screened by the ASIC app automatically. An ARDS suspicion is defined as deterioration of the paO2/FiO2 ratio ≤300 mm Hg that occurs under a PEEP ≥5 cmH2O. In case of ARDS suspicion, the physician will be informed and has to evaluate a potential diagnosis by checking the non-automated criteria of ARDS. These include (1) an acute onset of lung injury within 1 week of an apparent clinical insult and with progression of respiratory symptoms, (2) presence of bilateral opacities on chest imaging (chest radiograph or CT) not explained by other lung pathology (eg, effusion, lobar/lung collapse or nodules) and (3) respiratory failure not explained by heart failure or volume overload. According to the Berlin definition, three severity stages of ARDS (mild, moderate, severe) are categorised based on the degree of hypoxemia using the paO2/FiO2 ratio.11 If the diagnosis has been made by the physician, the ASIC app displays the relevant recommendations of the German S3 guideline ‘Invasive ventilation and use of extracorporeal procedures in acute respiratory insufficiency’4 and requests the physician to evaluate applicability of these recommendations for the individual patient. Responsibilities for diagnostic and therapeutic decisions remain with the physicians in charge. If the ARDS diagnosis is not verified, a 24-hour blocking period follows, in which the app does not issue any further notifications. If screening for ARDS remains positive, the app will ask the physician for re-evaluation after 24 hours.

Project design

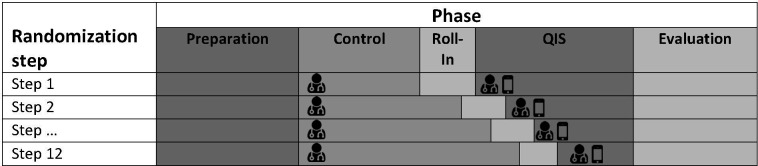

This paragraph describes the initial design of the project as it was planned before the start of control phase. The project is designed as a multicentre stepped-wedge cluster randomised quality improvement strategy (QIS).12 It will be conducted at 8 German university hospitals: Aachen (8 ICUs/96 beds), Bonn (4/58), Duesseldorf (1/16), Halle a. d. Saale (2/30), Hamburg-Eppendorf (10/116), Jena (2/50), Leipzig (3/78) and Rostock (1/23). Since not all of these 31 ICUs are technically and organisationally independent, the dependent ICUs will be summarised into clusters. This results in a total of 12 clusters available for randomisation, of which each will be randomised to one of the 12 steps. After a preparation phase of 18 months, all participating clusters start with a control phase (standard of care) simultaneously. After 8 months, the first clusters enter the roll-in phase (3 months) that is followed by the actual QIS phase. The remaining clusters follow in a stepwise fashion with 1 month between each step (figure 1). During the control phase, the status quo in diagnosis and therapy of ARDS is recorded without any interventions and change in clinical routine. According to the randomisation scheme, the ASIC app will be implemented on the participating ICUs during the roll-in phase to ensure clinical and technical functionality and adequate training of the ICU staff. 3 months later, the QIS phase will start, using the ASIC app in clinical routine. In this phase, the physicians will be assisted to optimise diagnosis and guideline-adherent therapy of ARDS by the ASIC app. Except for the app-usage, there are no further changes in routine caregiving. The final evaluation of primary and secondary key performance indicators (KPIs) (see below) will take place in the evaluation phase.

Figure 1.

Stepped-wedge design. During the control phase, ARDS detection is performed according to local standard by the physician in charge with beginning of the QIS phase, physician’s ARDS diagnosis is supported by the ASIC app. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; QIS, quality improvement strategy.

Population under surveillance

All patients ≥18 years of age in the participating ICUs, who are mechanically ventilated for at least 24 hours, will be admitted to the project. According to pre-existing data from the local EHRs, we expect approximately 5000 patients per year to be surveyed within the project.

Key performance indicators

The coprimary KPIs of the project consist of the diagnostic rate, defined as the proportion of patients diagnosed with ARDS out of all monitored patients, and guideline adherence regarding lung-protective ventilation, defined as shown below (see table 1).

Table 1.

Coprimary and secondary key performance indicators of ASIC

| Coprimary key performance indicators | Secondary key performance indicators |

|

1. Prevalence of organ dysfunction within 28 days after diagnosis of ARDS or ICU discharge (whatever occurs first), defined as days without need of following measures:

|

2. Guideline adherence regarding lung-protective ventilation, defined as the percentage of time within 28 days after ARDS diagnosis or ICU discharge (whatever occurs first), during which the mechanical ventilation parameters fulfil the following criteria:

|

2. Treatment-duration on ICU after ARDS diagnosis |

| 3. Hospital mortality after ARDS diagnosis | |

4. Acceptance and usability of the ASIC app and the mobile device:

|

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit.

Secondary KPIs include the prevalence of organ dysfunction within 28 days after ARDS diagnosis or ICU discharge (whatever occurs first). The treatment duration on ICU and the hospital mortality after ARDS diagnosis will be assessed at hospital discharge, irrespective of length of stay.

Furthermore, the user acceptance and usability of new technologies in medicine, such as mobile devices or clinical decision support systems will be examined. Therefore, a survey among the app users will be conducted before and after the ASIC app implementation, in order to investigate user acceptance of mobile technical support systems within clinical routine.

Clinical data collection and data protection

The total data collection started in July 2019 and is scheduled to be completed in December 2021. All data used by the ASIC app or included in the analysis are primarily displayed and stored in the local EHR (tables 1–3). At admission to the ICU, the body height of the patients will be measured using disposable measuring tape in order to determine the predicted body weight for calculating the tidal volume according to ARDS network.13 Predicted body weight is computed in men as 50 + (0.91×[height in centimetres − 152.4]) and in women as 45.5+(0.91×[height in centimetres − 152.4]). The diagnosis of ARDS is assumed to be made when the international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-10) code J80.x is documented, depending on severity of disease. The onset of ARDS in the control phase is defined as the time, when the paO2/FiO2 ratio decreases consistently ≤300 mm Hg, that is, during a period of 2 hours or in two consecutive arterial blood gas analyses, if the time interval between them is longer than 2 hours. During the QIS, the onset of ARDS is assumed, when the physician diagnoses an ARDS using the app. Data are collected from admission to the project until discharge from hospital. Patients who develop ARDS will be assessed for their outcomes when discharged from ICU or 28 days after diagnosis (whatever occurs first) and at hospital discharge depending on the outcome parameter. For a detailed summary, which parameter is collected at which time point, please refer to table 2.

Table 2.

Patient-related data acquisition

| Acquired data at inclusion | |

| Demographic data | Age, sex, height, weight, body mass index, predicted bodyweight (according to the ARDS network) |

| Acquired data at diagnosis of ARDS | |

| Therapeutic interventions | Prone positioning |

| Acquired data 28 days after diagnosis of ARDS or ICU discharge (whatever occurs first) | |

| Guideline adherence | Time fraction of guideline adherent therapy. Included parameters:

|

| Days without organ dysfunction | Full days without organ replacement therapy:

|

| Acquired data at hospital discharge | |

| Duration of treatments | Duration of hospital treatment, duration of ICU treatment, duration of hospital treatment until ARDS diagnosis |

| Mechanical ventilation | Duration of mechanical ventilation (excluding atelectasis-prophylaxis) |

| Mortality | In-hospital mortality of ARDS, ICU mortality of ARDS |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 3.

Clinical data collected during the project

| Category | Parameters |

| Scores | Glasgow Coma Scale, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score |

| Vital parameters | Heart rate, oxygen saturation, arterial blood pressure (systolic, diastolic, mean pressure), central venous pressure, body temperature, 24 hours fluidbalance |

| Haemodynamic monitoring | Pulmonary artery pressure (systolic, diastolic, mean pressure), Pulmonary artery wedge pressure, extravascular lung water index, global enddiastolic volume index, cardiac output, cardiac index, stroke volume, stroke volume index, systemic vascular resistance index, pulmonary vascular resistance-index |

| Parameters of mechanical ventilation | Respiratory rate (measured, spontaneous), inspiration-to-expiration-ratio (I:E-ratio), tidal volume per predicted bodyweight, inspiratory oxygen fraction, expiratory oxygen raction, end-inspiratory-pressure (pEI), positive endexpiratory pressure (PEEP), driving pressure (Δp=pEI PEEP), lung compliance, endexpiratory CO2 |

| Laboratory parameters | Leucocytes, haemoglobin, haematocrit, platelets, CRP, procalcitonin (PCT), urea, creatinine, brain natriuretic peptide, bilirubin, albumin, aspartate-amino-transferase (AST), alanine-amino-transferase (ALT), troponine, creatinkinase, creatinkinase isoform MB, amylase, lipase, international normalised ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time |

| Blood gas analysis | pH, paO2, paCO2, SaO2, lactate, bicarbonate, ScvO2, base excess, paO2/FiO2 ratio |

| Medication | Nitric oxide inhal., iloprost inhal., dobutamine iv, epinephrine iv, norepinephrine iv, vasopressin iv, milrinone iv, levosimendan iv, propofol iv, midazolam iv, clonidine iv, dexmedetomidine iv, S-ketamine iv, isoflurane inhal., sevoflurane inhal., sufentanil iv, fentanyl iv, morphine iv, rocuronium iv, furosemide iv, hydrocortisone iv, prednisolone iv, dexamethasone iv, terlipressin iv, fludrocortisone iv |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenator (ECMO) | Veno-venous ECMO (VV-ECMO), venoarterial ECMO (VA-ECMO), extracorporeal bloodflow, extracorporeal gasflow, oxygenfraction of extracorporeal gasflow |

CRP, C reactive protein; FiO2, fractional inspired oxygen; inhal., inhalative; i.v., intravenous; paCO2, arterial carbon dioxide tension; paO2, arterial oxygen tension; paO2, arterial oxygen tension; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; ScvO2, central venous oxygen saturation.

The data usage takes place within the secure networks of the participating hospitals. When the patient has been discharged, the collected data are transferred to the local Data Integration Centre (DIC), where they are anonymised. The DIC of each location enables medical data sharing across institutional boarders to improve patient care and clinical research. The establishment of these DIC is intended to create a sufficiently large database to allow further analyses. This could help to identify further risk factors with diagnostic or prognostic relevance for ARDS in the future, using, for example, current methods of data science.

Comprehensive validation of data protection issues was carried out by external legal consultants. Furthermore, a data protection concept was developed by external data protection experts for the concrete data protection processes in accordance with the local data protection commissioners (eg, data transfer, anonymisation and data storage).

Proposed sample size

To check whether the size of the sample we expect to collect in the 12 clusters will suffice to detect a difference in ARDS diagnosis rates with 80% power, we did a power calculation as proposed by Hussey and Hughes14 using the R package swCRTdesign15 in R (V.3.5.1).16 This package implements power calculations that take into account the particular characteristics of stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trials such as within-cluster correlations as shown in the article by Hussey and Hughes.14

Based on the expected case numbers of 5000 Patients/year, we assumed a mean of 1041 patients per cluster for the study duration of 2.5 years. For the ARDS diagnosis rate in the control phase we used incidences from Brun-Buisson et al17 and Bellani et al1 which suggest a rate of 16.1% and 23.4%, respectively. Under both of these baseline rates an increase as small as 1% (eg, from 16.1% to 17.1%) could be detected with at least 80% power.

Statistical analysis

To provide explorative evidence of improvement in healthcare of ARDS patients, differences in primary and secondary KPIs between control phase and QIS will be tested using generalised linear mixed models, where the level of clustering is the 12 clusters. The hypotheses tested for the coprimary KPIs are:

(A) The ARDS diagnosis rate in the QIS phase () is higher than the rate in the control phase ():

(B) The percentage of lung protective ventilation time in the QI phase () is higher than the percentage in the control phase ():

We will conduct two-sided significance tests with a significance level of 5% and also use point estimates and their 95% CI to judge the effect. Secondary KPIs will be analysed descriptively and if feasible with exploratory hypothesis tests following the modelling approach of the primary KPIs.

Patient and public involvement

ASIC is carried out in the routine care of critically ill patients. It fosters the timely diagnose and the adherence to existing guidelines and does not introduce new therapeutic measure. Due to that fact, patients were not included into the planning of the project. During the development of the ASIC app, physicians, who were supposed to use the app, contributed to a user-friendly design of the app. Additionally, surveys among the using physicians will be carried out to evaluate the physician’s view onto the app. At last, patient and public involvement will be reached by the SMITH Congresses 2019 and 2022 (https://www.smith.care/) and the activities of the German ‘Medical Informatics Initiative’ (https://www.medizininformatik-initiative.de/).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics review, registration and informed consent

Ethical approval was obtained from the independent Ethics Commitee (EC) at the RWTH Aachen Faculty of Medicine (local EC reference number: EK 102/19) as well as the respective data commissioner in March 2019. The use case ASIC is registered at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00014330) and will be conducted according to the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The collection of routine documentation on which the ASIC app operates does not require an informed consent because the app merely serves as a supplement to the existing EHR, which will remain the main resource in patient data management.

Access to data and dissemination

The results of the ASIC QIS will be presented at scientific and medical conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals. ASIC was created to demonstrate the possibilities offered by advanced digital services and infrastructure in healthcare, and therefore, serves as an exemplary use case with clinical benefit in order to prove the functionality of the DIC infrastructure within the SMITH consortium. One of the main objectives of establishing DIC at the local sites is to facilitate the exchange and use of medical data across the borders of institutions and geographical locations in interoperable data formats for medical research while meeting the data protection and security laws and requirements.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @bickenbach_j, @ScheragAndre

Contributors: GM and ASchu developed the concept and design of the ASIC use case. OM, SD and JK worked as project managers for the SMITH project and coordinated the use case. SJF, JBK, OM, SD and JB wrote the manuscript. GM, JB, SJF, JBK, CP, SZ, FE, RK, KK, FS, SK, SG, LH, FB, PS, NJ and TS were responsible for the extraction and summary of the guideline recommendations for the ASIC app. VL and NKV developed the technical architecture of the ASIC app and supervised the programming of the ASIC app. SH, IL, SZ, FE, DG, SB, JP, PJ, DT, EW, DA, SM, TW and PG worked on the technical implementation of the DIC at their respective centres and the data extraction for the ASIC app. ASchu, RP, KS, HM, LK, WS, RB, JL, MR, CB, ASto and SF worked on the identification of unknown risk factors with diagnostic and prognostic relevance for ARDS. ASche and JP provided feedback regarding the study design and the statistical analysis. GM and VL worked on legal issues concerning the implementation of the ASIC app. VL, NV, SH, IL worked on technical issues concerning the implementation of the ASIC app. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The SMITH consortium is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research with the grant code 01ZZ1803A-T. Aachen University Hospital: 01ZZ1803B, Jena University Hospital: 01ZZ1803C, Leipzig University Hospital: 01ZZ1803D, and Halle University Hospital: 01ZZ1803N, Bonn University Hospital: 01ZZ1803Q, Hamburg University Hospital: 01ZZ1803O, RWTH Aachen University: 01ZZ1803K, Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH: 01ZZ1803M, Bayer AG: 01ZZ1803I, University Medical Center Rostock: 01ZZ1803R, Düsseldorf University Hospital: 01ZZ1803T.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA 2016;315:788–800. 10.1001/jama.2016.0291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phua J, Badia JR, Adhikari NKJ, et al. Has mortality from acute respiratory distress syndrome decreased over time?: a systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:220–7. 10.1164/rccm.200805-722OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1685–93. 10.1056/NEJMoa050333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamzik M, Bauer A, Bein T. S3-Leitlinie invasive Beatmung und Einsatz extrakorporaler. Verfahren bei akuter respiratorischer Insuffizienz. AWMF-Leitlinie, 2017. https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/001-021l_S3_Invasive_Beatmung_2017-12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amato MBP, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015;372:747–55. 10.1056/NEJMsa1410639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrucci N, De Feo C. Lung protective ventilation strategy for the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD003844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herasevich V, Yilmaz M, Khan H, et al. Validation of an electronic surveillance system for acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:1018–23. 10.1007/s00134-009-1460-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKown AC, Brown RM, Ware LB, et al. External validity of electronic sniffers for automated recognition of acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Intensive Care Med 2019;34:946-954. 10.1177/0885066617720159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter A, Stäubert S, Ammon D, et al. Smart medical information technology for healthcare (Smith). Methods Inf Med 2018;57:e92–105. 10.3414/ME18-02-0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semler SC, Wissing F, Heyder R. German medical informatics initiative. Methods Inf Med 2018;57:e50–6. 10.3414/ME18-03-0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 2012;307:2526–33. 10.1001/jama.2012.5669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, et al. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 2015;350:h391. 10.1136/bmj.h391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1301–8. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:182–91. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes J, Hakhu NR. swCRTdesign: stepped wedge cluster randomized trial (SW crt) design. R package version 22 2018.

- 16.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brun-Buisson C, Minelli C, Bertolini G, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of acute lung injury in European intensive care units. results from the alive study. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:51–61. 10.1007/s00134-003-2022-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.