Abstract

Background

Osteoporosis is a public health problem in the elderly wherein a decrease in bone mass and mineral density increases the at risk of fractures. Panchatikta Ghrita (PG) is a classical Ayurvedic formulation that may help slow bone degeneration.

Objective

This experimental study was conducted to assess the efficacy of Panchatikta ghrita (PG) in protecting against postmenopausal osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats.

Materials and methods

The experiment was initiated after Institutional Animal Ethics Committee approval. 96 female Sprague Dawley rats were divided into 8 groups viz. sham control (NC), diseased control (DC), vehicle control (VC), 3 test drug (PG) groups (PG1, PG2 & PG3 - 0.9, 1.8 and 2.7gm/kg body weight respectively) and 2 standard control (SC) groups - SC1 received 17α-ethinylestradiol 1μg/kg/day while SC2 received alendronate (7mg/kg/week). Study medications were administereddaily for four months. Bone specific biomarkers viz. osteocalcin and TRAP-5b were estimated at baseline and end of study. Animals were sacrificed on day 121 and their femurs and tibiae were harvested for histomorphometric analysisand bone microarchitectural studies.

Results

Serum osteocalcin and TRAP-5b showed significant increase (p < 0.001) in levels in DC group as compared to sham controls. All 3 doses of PG decreased bone specific biomarker levels with maximal effect seen with highest dose of PG similar to that seen with standard drugs. PG also significantly improved bone micro architectural parameters like bone mineral density and mineral content at higher dose levels. Decrease in osteoclasts and significant dose dependent increase in bone hardness and elasticity was seen with PG which was comparable to standard drugs.

Conclusion

PG increased bone mineral density and content, decreased turnover of bone specific biomarkers and osteoclast formation, indicating its protective effect against experimentally induced postmenopausal osteoporosis.

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis affects bones by decreasing bone mass and bone mineral density, thus making the bone more fragile and at a higher risk of fractures [1]. Osteoporosis has become a global public health concern with the acceleration of ageing in the population especially among women [2], [3], [4]. The results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA) revealed that women aged 50 years or older with no previous diagnosis of osteoporosis had a higher prevalence of osteopenia (39.6%) and osteoporosis (7.2%) following menopause with an higher predictive risk for fractures [5].

Osteoporosis is a slowly progressive disease and so it takes several years before the beneficial effect of medications is observed both in humans and animals. Hence, selecting a suitable animal model that reliably replicates the disease condition and demonstrates the benefits of medicines being evaluated on Osteoporosis is important. The United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has approved the ovariectomized rat model as an appropriate preclinical model to study the potential beneficial effects of different therapeutic interventions postmenopausal osteoporosis inspite of its limitations [6], [7], [8].

Estrogen replacement is the best therapy to decrease postmenopausal bone loss, serious side effects like thromboembolism have been seen with a reported 75% discontinuation rate at 6 months [9] and is thus recommended only for those women who are already using hormone replacement for menopausal symptoms. Although drugs like the bisphosphonates and Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) like raloxifene are used to treat osteoporosis, they have side effects that affect patient adherence in the long term. Thus, researchers and the medical fraternity are now focusing attention on the plant kingdom and looking for clues among the different traditional systems of medicine to treat chronic debilitating diseases like osteoporosis.

Although “osteoporosis” has not been directly mentioned in the ayurvedic texts; there are references that describe a decrease in “asthi” or bone as a person grows older. Decrease in “asthi” causes an imbalance of the vata dosha thus weakening the bone structure and thickness. Plants with tikta (bitter) and katu (pungent) properties are said to reverse this imbalance in the dosha [10], [11]. Panchatikta Ghrita (PG) is a classical Ayurvedic formulation that contains 5 plants with these properties viz. Azadirachta indica (Nimba), Trichosanthes dioica (Patola), Solanum surattense (Kantakari), Tinospora cordifolia (Guduchi) and Adhatoda vasica (Vasa) and so is claimed to help in slowing the process of bone degeneration which is useful in conditions like osteoarthritis. The processed ghee “ghrita” in the formulation acts like a vehicle for these plants to reach the level of the bones to exert a maximum effect [12].

Thus, the present study was undertaken to evaluate whether administration of PG would help in preventing the progression of bone degeneration in postmenopausal osteoporosis in an ovariectomised model in Sprague Dawley (SD) rats.

2. Materials and methods

Institutional Animal Ethics Committee for animal experimentation was obtained prior to study initiation [IAEC project No. 2015/01]. The study was carried out at the Central Animal House, TNMC and BYL Nair Ch. Hospital, Mumbai Central, Mumbai 400 008.

2.1. Animal species for the study

4 month old female Sprague Dawley rats weighing between 280 and 300 gms were used in the study. This particular species was selected as osteoporosis has been found to occur more readily in SD rats as compared to Wistar rats as measured by bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar region [13]. The rats were housed in the Central Animal House facility approved by CPCSEA, a statutory body under Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change, Government of India at 22 °C ± 2 °C and 40% humidity with a 12/12-hour light/dark cycle. All rats were provided free access to normal rat pellet diet and purified water.

2.2. Chemicals

17α-ethinyl estradiol and alendronate were purchased from M/s Sigma–Aldrich, USA. Other chemicals and reagents required for the study were purchased from SD Fine Chemicals Ltd., Mumbai, India.

2.3. Plant medication

Panchtikta ghrita (PG) was procured from Sampurna Jeevan Pharmachem Pharmaceuticals (P) Ltd., Yadrav, Kolhapur, a GMP certified ayurvedic pharmacy. The formulation was prepared as per the Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India, Part II (formulations). Vol I, Part-I, 6:26 (No.31) [14]. Quality control analysis was performed on the prepared medication prior to use in the study. The details of the plant ingredients present in the formulation is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of the ingredients present in Panchatikta ghrita (PG) classical herbal formulation as per API.

| No | Plant name | Local name | Plant part | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Azadirachta indica | Nimba | Stem & bark | 480 g |

| 2 | Trichosanthes dioica | Patola | Plant | 480 g |

| 3 | Solanum xanthocarpum | Kantakari | Plant | 480 g |

| 4 | Tinospora cordifolia | Guduchi | Stem | 480 g |

| 5 | Adhatoda vasica | Vasa | root | 480 g |

| Jala for decoction | Water | 12.29L | ||

| reduced to | 3.07L | |||

| 6 | Terminalia chebula | Haritaki | Fruit | 128 g |

| 7 | Terminalia bellerica | Bibhitaki | Fruit | 128 g |

| 8 | Phyllanthus embelica | Amlaki | Fruit | 128 g |

| 9 | Ghee as vehicle | Ghrita (Goghrita) | Clarified butter from cow's milk | 768 g |

2.4. Study procedure

There were 8 study groups with 12 rats in each group (n = 96 rats). Group 1 (12 animals) acted as the sham control group (NC). The remaining 84 animals were to be ovariectomized using the dorso-lateral abdominal incision under ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/ml) and xylazine (1 mg/ml) induced anesthesia given intraperitoneally. With the permission of the IAEC, an additional 14 rats (2 per group for 7 groups) were ovariectomized so as to obtain 12 rats which had reached the diestrous stage and could be taken up further for the study. The stage of oestrus cycle was confirmed by performing vaginal swab test on days 0, 7, 14 and 28 post-surgery. Only those animals which were consistently in the diestrous stage were then randomly divided into seven groups. Group 2 acted as the diseased control (DC) and did not receive any treatment post-surgery. Group 3 was the vehicle control (VC) group and received only pasteurized milk orally. Groups 4, 5 and 6 were the test control groups and were administered 3 doses of PG viz., 0.9, 1.8 and 2.7 gm/kg respectively with pasteurized milk as the vehicle. These doses were extrapolated from the clinical dose of PG i.e. 10–20 g per day to be taken with milk [12]. Groups 7 & 8 were the standard control (SC) groups receiving estrogen therapy (17α-ethinylestradiol 1 μg/kg/day daily, subcutaneously) or alendronate (7.2 mg/kg/orally daily). 2 positive controls were used as these are the drugs commonly prescribed for the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. All the study groups received the study drugs & vehicle for a period of 4 months (120 days).

2.5. Assessment parameters

Serum and urine samples were processed at monthly intervals for calcium estimation using Colorimetric Arsenazo III method and inorganic phosphate using phosphomolybdate UV endpoint method.

2 bone specific biomarkers viz. serum osteocalcin, a specific biomarker of osteoblast function which is used to measure bone formation rate in osteoporosis and TRAP 5b, which is secreted by osteoclasts during bone resorption and is frequently used as a bone resorption marker were used to assess bone turnover in the study. These were estimated at baseline and at the end of the study period using double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits procured from Shanghai Korain Biotech Co Ltd, China. The sensitivity of the kits was 0.02 ng/ml for rat Osteocalcin assay and 0.022 U/L for the rat TRAP 5b assay.

Bone histomorphometric analysis [15] using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining was carried out on one set of excised femurs and tibiae of the animals once they had completed the study period and were euthanized on day 121 by carbon dioxide inhalation as per CPCSEA guidelines.

The second set of excised femurs and tibiae was evaluated to assess bone microarchitecture. The micro SPECT/CT images were acquired using a micro PET/CT/SPECT tri-modality gamma imaging system (Triumph@, Gamma Medica Ideas, Northridge, CA, USA). The samples were scanned at 40 keV voltage, with exposure time of 600 ms. The focal spot was 84 μm with 4 magnification having field of view (FOV) 29.3 mm. The acquisition time was 38 min. Bone mineral density (BMD), bone mineral content (BMC), trabecular bone volume (BV/TV, %), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp, mm) and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th, mm) parameters were calculated using the MicroView (V 2.4) software.

Bone hardness and bone elasticity was also studied using the nanoindentation technique [16]. The indentation was carried out using CSM-Instrument make Ultra-Nano Hardness tester. Spherical diamond indenter with 5 μm radius was used for indentation. Indentation was carried out by following Oliver and Pharr method. Spherical indenter was used to avoid crack formation. Predefined load of 5 mN was applied on the bone samples. Loading unloading rate was kept 10 mN/min with 30sec hold time at maximum load to avoid creeping of the sample.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as Mean ± Standard Deviation. All experimental data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison posthoc test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Biochemical parameters

Blood and urine samples were collected on days 0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 for the measurement of serum calcium and inorganic phosphate. Bone specific biomarkers viz. serum osteocalcin and serum TRAP 5b estimation were done at baseline and at the end of the study period using elisa kits.

3.1.1. Effect on blood & urine parameters

A decrease in serum calcium and increase in urine calcium was observed in the diseased group as compared to sham control group and vice versa in case of serum and urine inorganic phosphorus levels at day 120. Panchtikta ghrita, in a dose dependent manner, increased the serum calcium and lowered phosphorus levels when compared to the disease control group. However these changes were not statistically significant.

3.2. Effect on bone specific biomarkers

3.2.1. Serum osteocalcin

A significant increase in serum osteocalcin levels was observed in the diseased control group which was lowered by Panchtikta ghrita at all the 3 doses tested, with maximum effect seen with the highest dose used i.e. 2.7 mg/kg body weight. The lowering of osteocalcin levels seen with PG was similar to that seen with oestrogen therapy while alendronate lowered osteocalcin levels to a much greater extent. The results are represented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effect on Serum Osteocalcin (n = 12). #p < 0.001 as compared to the Normal Control group. *p < 0.001 as compared to the Disease Control group. (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test).

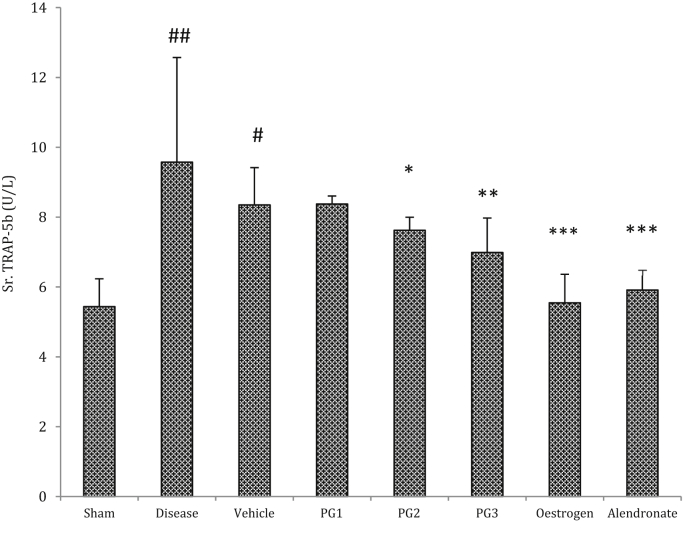

3.2.2. Effect on Serum TRAP 5b

An increase in serum TRAP-5b levels was observed in diseased group as compared to sham control and vehicle control groups. All the 3 doses of Panchtikta ghrita exhibited dose dependent decrease in Trap-5b levels, with maximum effect seen with the highest dose used i.e. 2.7 mg/kg body weight. Both the standard drugs used also showed a significant reduction. The results are represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effect on Serum TRAP 5b (n = 12). #p < 0.01, ##p < 0.001 as compared to the Normal Control group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 as compared to the Disease Control group. (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test).

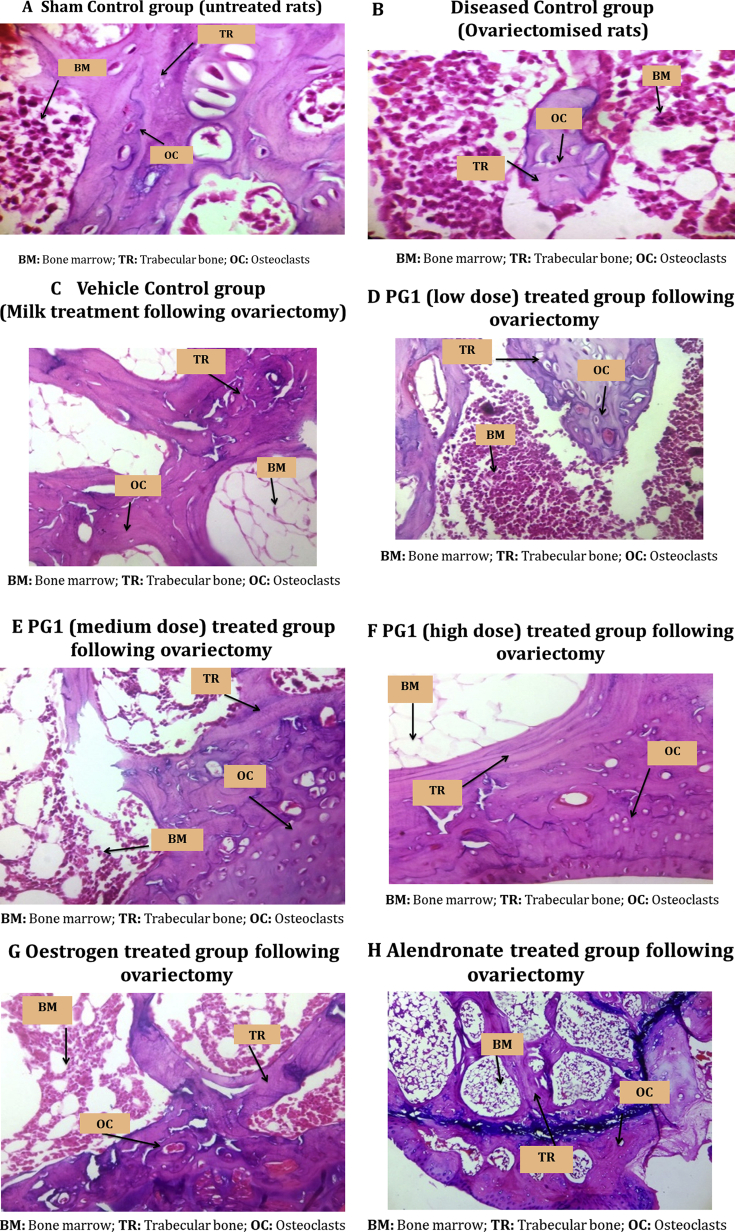

3.3. Histomorphometrical analysis

Following sacrifice of the animals on day 120, the femur bones were excised using bone cutter and cleaned to remove any remains of muscle fibers. The bones were deposited in 10% formalin solution for histomorphometric parameters. The results of histomorphometric analysis are summarized as follows:

3.3.1. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining

The disease control group showed highest bone damage score as the bone was totally damaged/resorbed with increased osteoclast formation and decreased trabecular thickness as compared to the sham control indicating osteoporotic condition. PG showed a dose dependent decrease in the total bone damage score with maximum effect seen in the highest dose tested which was similar to that seen with the 2 standard drugs used. The results are summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Observations of Hematoxylin and Eosin staining.

| Reduced trabecular Thickness | Depleted Bone Marrow | Resorption of bone | Osteoclast formation (multinucleated) | Total Bone damage Score (Total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal/Sham Control | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | 0 |

| Disease Control | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | 10 |

| Vehicle Control | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | 9 |

| PG low dose (PG1) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | 8 |

| PG medium dose (PG2) | ++ | ++ | + | + | 6 |

| PG high dose (PG3) | + | + | + | + | 4 |

| Oestrogen | + | + | + | ++ | 5 |

| Alendronate | + | + | + | + | 4 |

Note: + = Mild Change; ++ = Moderate change/Damage; +++ = Severe change/Damage.

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs of the lower end of the femur bone stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin depicting the effect of the study drugs on bone damage (H & E, 400X).

3.3.2. TRAP staining

TRAP staining showed that there was a significant increase in the number of osteoclasts in the epiphyseal and metaphyseal, paratrabecular and medullary regions of the bone in the diseased group as compared to the sham control. PG treated rats showed a significant decrease in the number of osteoclasts at medium and high doses tested which was comparable to the standard drugs. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Effect of the study drugs on the number and distribution of Osteoclasts.

| Groups | Metaphyseal & epiphyseal region | Paratrabecular region | Medullary bone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 1.5 ± 0.32 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0 ± 0 |

| Diseased | 7.5 ± 2.03# | 2.5 ± 1.3# | 1.5 ± 0.3# |

| Vehicle | 6.5 ± 2.33# | 2.5 ± 1.5# | 1.3 ± 0.5# |

| PG low dose (PG1) | 5.5 ± 1.64# | 1.83 ± 1.05# | 1.3 ± 0.53# |

| PG medium dose (PG2) | 3.5 ± 1.04* | 1.98 ± 0.24* | 0.66 ± 0.52* |

| PG high dose (PG3) | 2.33 ± 1.03* | 1.25 ± 0.15* | 0.5 ± 0.55* |

| Oestrogen | 1.5 ± 0.3* | 0 ± 0* | 0 ± 0** |

| Alendronate | 1.33 ± 0.5* | 0.3 ± 0.01* | 0 ± 0** |

#p < 0.001 as compared to the Normal Control group; ∗p < 0.05 as compared to the Disease Control group; ∗∗p < 0.001 as compared to the Disease Control group (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test).

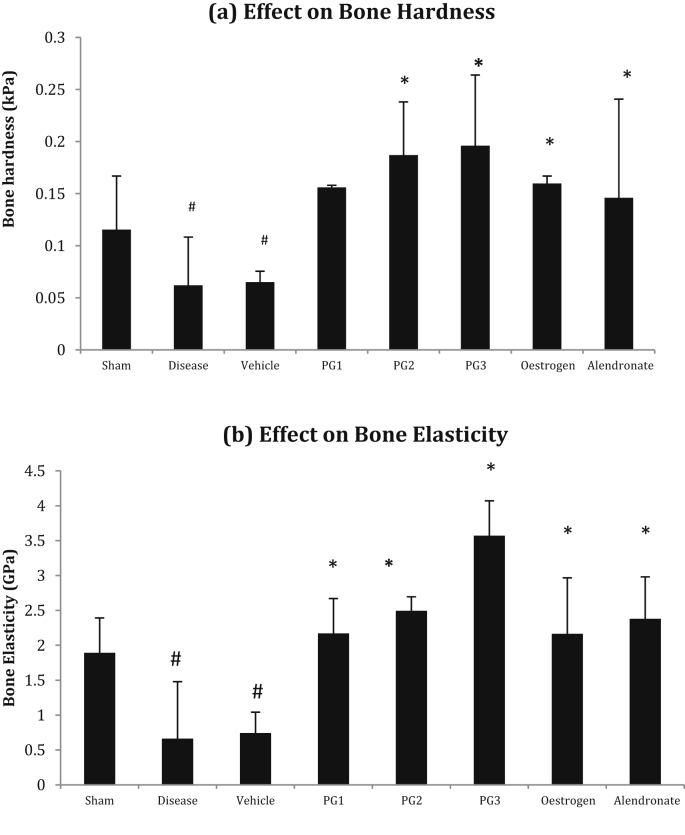

3.4. Bone hardness & elasticity assessed by the nano-indentation method

Bone hardness and elasticity were found to be low in the diseased group as compared to the Sham control group. Panchatikta ghrita treated rats showed a significant dose dependent increase in bone hardness and elasticity as compared to the disease control group and the effect at the lowest dose (0.9 gm/kg) was comparable to that exhibited by the Standard drugs. The results obtained on hardness and elasticity of bones are summarized in Fig. 4 (a) & (b).

Fig. 4.

Effect on Bone Hardness and Bone Elasticity. #p < 0.05 as compared to the Normal Control group. *p < 0.001 as compared to the Disease Control group. (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test).

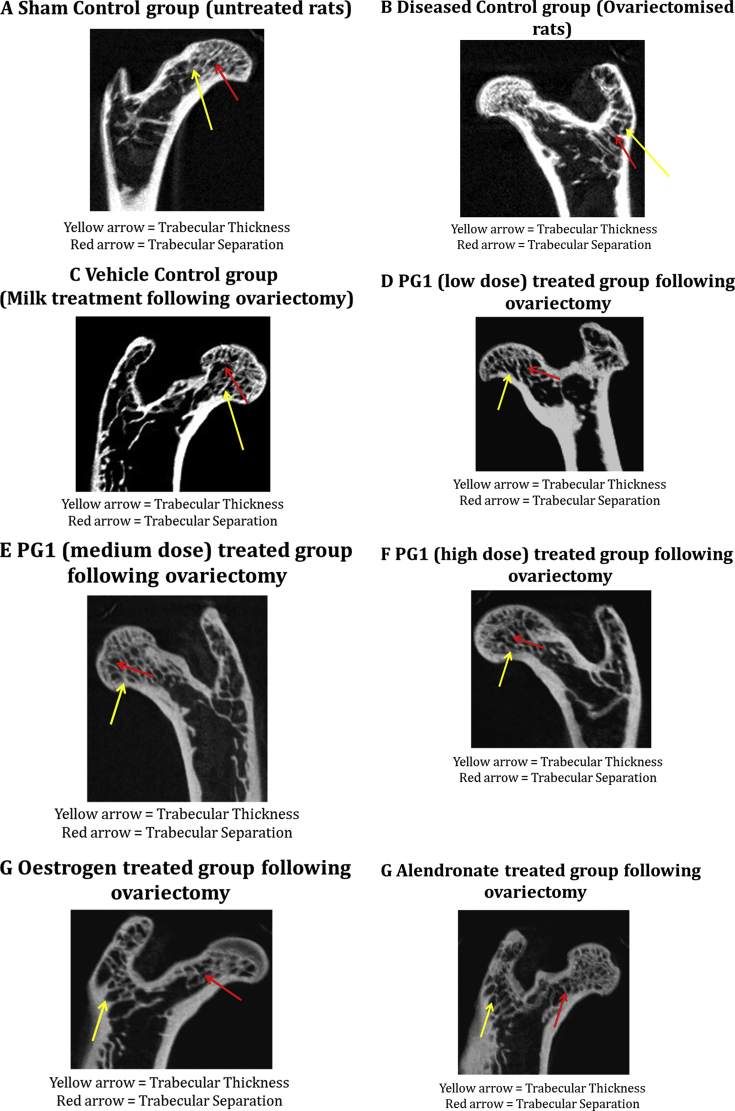

3.5. Bone microarchitecture

Micro-CT was used to assess changes in the bone microarchitecture of the excised femor & tibia samples. Bone mineral density (BMD), bone mineral content, trabecular bone volume (BV/TV, %), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp, mm) and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th, mm) were estimated using a software. A decrease in all the bone microarchitecture associated parameters was observed in the diseased control All the study drugs improved the bone micro architectural parameters like bone mineral content and mineral density, trabecular thickness and bone volume as compared to DC group. Panchtikta ghrita showed a dose dependent increase in these parameters. The maximum benefit was seen with Oestrogen therapy which was statistically significant. The results are summarized in Table 4 & Fig. 5.

Table 4.

Effect on Bone microarchitecture as seen by microCT studies.

| Groups | BMD | BMC | Trabecular thickness | Trabecular separation | Trabecular bone volume (BV/TV, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 476.23 ± 69.86 | 2331.44 ± 56.94 | 0.95 ± 0.009 | 1.15 ± 0.113 | 49.45 ± 2.44 |

| Diseased | 267.52 ± 39.65## | 1146.85 ± 42.88## | 0.79 ± 0.107 | 0.85 ± 0.025## | 37.4 ± 0.80## |

| Vehicle | 288.95 ± 54.34## | 1209.4 ± 83.55## | 0.80 ± 0.221 | 0.84 ± 0.221## | 42.37 ± 2.08## |

| PG low dose (PG1) | 328.96 ± 29.05##@@ | 1466.86 ± 58.66##∗∗@@ | 1.17 ± 0.005**@@ | 1.04 ± 0.005 | 55.29 ± 2.70##∗∗@@ |

| PG medium dose (PG2) | 375.83 ± 18.73#∗@@ | 1572.5 ± 14.59##∗∗@@ | 1.12 ± 0.256*@@ | 1.02 ± 0.131 | 56.87 ± 0.23##∗∗@@ |

| PG high dose (PG3) | 378.74 ± 77.54#∗@@ | 1697.91 ± 27.69##∗∗@@ | 1.05 ± 0.083*@@ | 1.1 ± 0.087* | 59.13 ± 1.45##∗∗@@ |

| Oestrogen | 502.99 ± 45** | 1971.94 ± 53.12##∗∗ | 2.68 ± 0.006##∗∗ | 1.21 ± 0.005** | 80.58 ± 2.89##∗∗ |

| Alendronate | 563.76 ± 52** | 1691.99 ± 51.45##∗∗ | 1.35 ± 0.007##∗∗ | 1.14 ± 0.057** | 64.19 ± 1.56##∗∗ |

#p < 0.05, ##p < 0.001 as compared to the Normal Control group; ∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.001 as compared to the Disease Control group; @p < 0.01 & @@p < 0.001 as compared to the Standard Control groups (ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test).

Fig. 5.

Micro CT images of the various experimental groups.

4. Discussion

Panchatikta Ghrita (PG), a classical ayurvedic formulation has plant ingredients that, as per Ayurveda, have properties of tikta rasa which maintains the dhatvagni in normal state which in turn keeps all the dhatus in the body in equilibrium. As asthi dhatu (related to bone tissue) becomes stable, bone degeneration decreases [11], [17]. Thus, this formulation, based on the osteoprotective properties of its plant ingredients, protects against bone degeneration and loss.

In our previous study, we had studied the protective effect of the same formulation against an experimental model of glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis [11]. The results demonstrated that Panchtikta ghrita protected against worsening of bone degeneration in this model of osteoporosis. Buoyed by these results, we wished to reconfirm whether the formulation benefits other hormone associated osteoporosis viz. that associated with menopause in both men & women. Thus, we selected the ovariectomized rat model of osteoporosis to assess the efficacy of this formulation in post-menopausal osteoporosis in women as this model is a validated pre-clinical model to test drug efficacy in osteoporosis [6], [8], [18]. We used oestrogen and alendronate as the positive controls as postmenopausal osteoporosis is mainly due to a decrease in the oestrogen level while alendronate, a bisphosphonate, is commonly used in clinical practice to treat osteoporosis [19], [20].

In our model, ovariectomy resulted in an increased risk of osteoporosis as seen in postmenopausal women. Serum calcium and phosphorous levels decreased following ovariectomy in the diseased group while there was an increase in the urinary levels of calcium and urine inorganic phosphatase. These results are in agreement with the results obtained by other researchers [21], [22], [23] suggesting that ovarian hormone deficiency following ovariectomy is marked by reduced intestinal calcium & phosphorus absorption and may contribute to the accompanying bone loss.

Osteocalcin is a molecule produced by osteoblasts as a marker for bone formation and thus serum osteocalcin is frequently used as the bone formation marker to monitor the drug action [24]. The ovariectomized rats in our study exhibited high levels of serum osteocalcin, which was similar to that reported by Kim et al. (2011) [25] & Kyung-Hyuk Yoon et al. (2012) [26] who demonstrated that ovariectomy caused a rise in serum osteocalcin level due to increased bone turnover. A dose dependent decrease in serum osteocalcin levels was observed following administration of Panchatikta ghrita with maximum benefit seen with the highest dose.

A similar trend was observed with serum TRAP 5b levels, a bone resorption biomarker of osteoclastic origin [27], [28], the levels of which are increased in osteoporosis indicating increased osteoclast activity. TRAP 5b level correlate inversely with estrogen level [29] and hence although we observed a statistically significant decrease in the serum TRAP 5b level with the study medications, the best results were seen with oestrogen therapy. These results are in agreement with those demonstrated by Rissanen JP et al. [30].

The nanoindentation technique helps in determining bone hardness and bone elasticity and is very useful in case of osteoporotic bones, especially as effect of therapy can also be determined at the level of the bone. Hardness of the bone depends on its inorganic mineral components while bone elasticity depends on connectivity between the organic and inorganic matrices [31], [32]. The bones of rats treated with Panchatikta Ghrita (PG) showed an increase in trabecular bone hardness and elasticity at all the doses tested as compared to the ovariectomised rats, which was comparable to both oestrogen and alendronate. Thus PG improves bone hardness and elasticity indicating its ability to decrease the risk of fractures.

Micro CT studies of the rat femur showed that there was a reduction in bone mineral density results in the diseased rats following ovariectomy at 4 weeks. This is similar to that seen by other researchers [33], [34] where they have shown that micro-CT scans of the femur and lumbar vertebrae had a significant reduction in bone mineral density 4 weeks after ovariectomy which further worsened at 8 weeks, thus confirming that the model successfully mimics the effects of osteoporosis.

Panchatikta ghrita, demonstrated a dose dependent increase in the bone mineral density (BMD) and bone mineral content (BMC) following treatment, with the effect seen by the highest dose similar to that shown by the standard medications, alendronate and oestrogen therapy which have been shown in previous studies to improve the microarchitecture of the bone following therapy in ovariectomised animals [35], [36], [37], [38].

Thus, ovariectomy resulted in a high bone turnover in the rats as seen with the changes in the bone specific markers and with damage to the trabecular bone as seen by a decrease in trabecular density and deterioration of bone microarchitecture resulting in decreased bone mineral content and density. Panchatikta Ghrita reduced the damage to the trabecular bone by reducing osteoclastic activity, slowing down bone turnover as seen by an improvement in bone specific marker levels and bone microarchitectural parameters like bone mineral density (BMD) and mineral content (BMC) confirming its potential as a herbal anti-osteoporotic agent. The results seen with this classical herbal formulation was similar to that seen with the drugs used in clinical practice viz. oestrogen replacement therapy or bisphosphonates like Alendronate.

Some of the limitations of our study were that we didn't study the effect of the ‘ghrita’, as it may have a more important role than just include being the vehicle. Also we didn't study the effect of the individual plant ingredients per se to determine whether any particular plant had the major beneficial effect or whether it was a synergistic effect of all the plant ingredients.

5. Conclusion

The present study thus demonstrated that Panchatikta ghrita had a stabilizing effect on the bone by decreasing bone degeneration and improving bone microarchitectural parameters. This resulted in a slowing of progression of the osteoporotic condition in postmenopausal rats. Thus, PG can be used as an alternative in early stages of osteoporosis (osteopenia) or as an adjuvant to prevent further bone degeneration and loss in those patients who are at risk of osteoporosis. The mechanism by which this formulation exerts its action at the molecular and cellular level however needs to be studied further using in vitro mechanistic studies. Further studies to confirm this classical ayurvedic formulation's protective effect on the bone in patients with osteoporosis also needs to be evaluated by conducting clinical studies.

Source(s) of funding

The study was conducted with financial support from the Department of AYUSH, Govt. of India (vide letter No. Z.28015/235/2015-HPC(EMR)-AYUSH dated 22/09/2015).

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the technical support provided by Ms. Deepali Ganachari, Ms. Jaya Varma and Ms. Ashwini Bhosale during the conduct of the study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Transdisciplinary University, Bangalore.

References

- 1.Dobbs M.B., Buckwalter J., Saltzman C. Osteoporosis: the increasing role of the orthopaedist. Iowa Orthop J. 1999;19:43–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reginster J.-Y., Burlet N. Osteoporosis: A still increasing prevalence. Bone. 2006;38(2):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey N., Dennison E., Cooper C. Osteoporosis: impact on health and economics. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(2):99–105. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boonen S., Singer A.J. Osteoporosis management: impact of fracture type on cost and quality of life in patients at risk for fracture I. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(6):1781–1788. doi: 10.1185/03007990802115796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siris E.S., Miller P.D., Barrett-Connor E., Faulkner K.G., Wehren L.E., Abbott T.A. Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286:2815–2822. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lelovas P.P., Xanthos T.T., Thoma S.E., Lyritis G.P., Dontas I.A. vol. 58. Copyright by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science; October 2008. pp. 424–430. (The laboratory rat as an animal model for osteoporosis. Research comparative medicine 2008). No 5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson D.D., Simmons H.A., Pirie C.M., Ke H.Z. FDA Guidelines and animal models for osteoporosis. Bone. 1995 Oct;17(Suppl. 4):125–133. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00285-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston B.D., Ward W.E. The overiectomized rat as a model for studying alveolar bone loss in postmenopausal women. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/635023. Article ID 635023, 12 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman R.S., Epstein R.S., Lydick E.G. Compliance of woman in taking estrogen replacement therapy. J Women's Health. 1996;5:213–220. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1996.5.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harishastri P., editor. Commentaries sarvangasundara of arundatta and ayurvedarasayana of hemadri on asthanghridaya of vagbhata, sootra sthan; doshadividnyaniyam adhyayam chapter no 11, verse 26–28. 6th ed. Krishnadas Academy, Chowkhamba press; Varanasi: 2000. p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munshi R.P., Patil T., Garuda C., Kothari D. An experimental study to evaluate the antiosteoporotic effect of Panchatikta Ghrita in a steroid-induced osteoporosis rat model. Indian J Pharmacol. 2016;48(3):298–303. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.182881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shastri R., editor. Commentary vidyotini of ambikadatta shastri on bhaishajya ratnavali of shri govindadas; kushtharog chikitsa: chapter no. 54. Verse 256–260. 14th ed. Chowkhambha Sanskrit Sansthan Publisher; Varanasi: 2001. pp. 633–634. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang J., Yang L., Zhang R., Zhu X., Wang P. Are there differences between Sprague-Dawley and Wistar rats in long-term effects of ovariectomy as a model for postmenopausal osteoporosis? Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(2):1491–1502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India, PART - II (formulations) volume - I Part-I, 6:26, first ed. (No.31) published by the government of India Ministry of health & family welfare. vol. 81. Department Of AYUSH; New Delhi: 2007. p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayman A.R., Bune A.J., Bradley J.R., Rashbass J., Cox T.M. Osteoclastic tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (Acp 5): its localization to dendritic cells and diverse murine tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:219–228. doi: 10.1177/2F002215540004800207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffler C.E., Guo X.E., Zysset P.K., Goldstein S.A. An application of nanoindentation technique to measure bone tissue lamellae properties. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127:1046–1053. doi: 10.1115/1.2073671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A.K., Shah N., Thakar A.B. Effect of majja basti (therapeutic enema) and asthi shrinkhala (Cissus quadrangularis) in the management of osteoporosis (Asthi-Majjakshaya) Ayu. 2012;33(1):110–113. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.100326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L., Chen X., Lv S., Dong M., Zhang L., Tu J. Influence of exercise on bone remodeling-related hormones and cytokines in ovariectomized rats: a model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. PLoS One. 2014;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells G., Tugwell P., Shea B., Guyatt G., Peterson J., Zytaruk N. Osteoporosis Methodology Group and the Osteoporosis Research Advisory Group. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of hormone replacement therapy in treating and preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(4):529–539. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bone H.G., Hosking D., Devogelaer J.P., Tucci J.R., Emkey R.D., Tonino R.P. Ten years' experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004;350 12:1189–1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulbaroud S., Mesfioui A., Arfaoui A., Ouichou A., Hessni A.E. Preventive effects of flaxseed and sesame oil on bone loss in overectomised rats. Pakistan J Biol Sci. 2008;11(13):1696–1701. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2008.1696.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassan H.A., EL Wakf A.M., El Gharib N.E. Role of phytoestrogenic oils in alleviating osteoporosis associated with ovariectomy in rats. Cytotechnology. 2013;65:609. doi: 10.1007/s10616-012-9514-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reinhold G., Silke E., Stangassinger B.M. Therapeutic efficacy of 1α, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and calcium in osteopenic ovariectomized rats: evidence for a Direct anabolic effect of 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 on bone. Endocrinology. 1998;139(10):4319–4328. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirwaikar A., Khan S., Malini S. Antiosteoporotic effect of ethanol extract of Cissus quadrangularis Linn. on ovariectomized rat. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;89:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim T.H., Jung J.W., Ha B.G., Hong J.M., Park E.K., Kim H.J. The effects of luteolin on osteoclast differentiation, function in vitro and ovariectomy-induced bone loss. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon K.H., Cho D.C., Yu S.H., Kim K.T., Jeon Y., Sung J.K. The change of bone metabolism in ovariectomized rats: analyses of MicroCT scan and biochemical markers of bone turnover. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;51:323–327. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.51.6.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shetty S., Kapoor N., Bondu J.D., Thomas N., Paul T.V. Bone turnover markers: emerging tool in the management of osteoporosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Nov-Dec;20(6):846–852. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.192914. doi: [10.4103/2230-8210.192914] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rico H., Villa L.F. Serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) as a biochemical marker of bone remodeling. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;52:149–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00308325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rico H., Arribas I., Villa L.F., Casanova F.J., Hernández E.R., Cortés-Prieto J. Can a determination of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase predict postmenopausal loss of bone mass? Eur J Clin Investig. 2002;32:274–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2002.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rissanen J.P., Suominen M.I., Peng Z., Halleen J.M. Secreted tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b is a Marker of osteoclast number in human osteoclast cultures and the rat ovariectomy model. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008 Feb;82(2):108–115. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9091-4. Epub 2007 Dec 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozcivici E., Ferreri S., Qin Y.X., Judex S. Determination of bone's mechanical matrix properties by nanoindentation. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;455:323–334. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-104-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiroušek Ondřej. Nanoindentation of Human Trabecular Bone – Tissue Mechanical Properties Compared to Standard Engineering Test Methods. In: Jiri Nemecek Dr., editor. Nanoindentation in Materials Science. IntechOpen; 2012. https://www.intechopen.com/books/nanoindentation-in-materials-science/nanoindentation-of-human-trabecular-bone-tissue-mechanical-properties-compared-to-standard-engineeri doi: 10.5772/50152. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elkomy M.M., Elsaid F.G. Anti-osteoporotic effect of medical herbs and calcium supplementation on ovariectomized rats. J Basic Appl Zool. 2015;72:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jobaz.2015.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin Y.H., Cho D.C., Yu S.H., Kim K.T., Cho H.J., Sung J.K. Histomorphometric analysis of the spine and femur in ovariectomized rats using micro-computed tomographic scan. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012 Jul;52(1):1–6. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.52.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.da Paz L.H., de Falco V., Teng N.C., dos Reis L.M., Pereira R.M., Jorgetti V. Effect of 17beta-estradiol or alendronate on the bone densitometry, bone histomorphometry and bone metabolism of ovariectomized rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:1015–1022. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000800007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClung M.R., San Martin J., Miller P.D., Civitelli R., Bandeira F., Omizo M. Opposite bone remodeling effects of teriparatide and alendronate in increasing bone mass. Arch Intern Med. 2013;165:1762–1768. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balena R., Toolan B.C., Shea M., Markatos A., Myers E.R., Lee S.C. The effects of 2-year treatment with the aminobisphosphonate alendronate on bone metabolism, bone histomorphometry, and bone strength in ovariecto-mized nonhuman primates. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:2577–2586. doi: 10.1172/JCI116872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azuma Y., Oue Y., Kanatani H., Ohta T., Kiyoki M., Komoriya K. Effects of continuous alendronate treatment on bone mass and mechanical properties in ovariectomized rats: comparison with pamidronate and etidronate in growing rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]