Abstract

Purpose

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have a significant and prolonged impact on health-related quality of life, patient outcomes, and escalation of pulmonary function decline. COPD-X guidelines published in 2003 subsist to facilitate a shift from the emphasis on pharmacological treatment to a more holistic multi-disciplinary interventions approach. Despite the existing comprehensive recommendations, readmission rates have increased in the last decade. Evidence to date has reported sub-optimal COPD guidelines adherence in emergency departments. This qualitative study explored contributing factors to interdisciplinary staff non-adherence and utilisation of COPD-X guidelines in a major Southern Queensland Emergency Department.

Methods

Semi-structured qualitative interviews with interdisciplinary staff were conducted in an emergency department. A purposive sample of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, pharmacist and a social worker were recruited. Interviews were digitally recorded, de-identified and transcribed verbatim. Data analysis followed a coding process against the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to examine implementation barriers and potential solutions. Identified factors affecting non-adherence and underutilisation of guidelines were then mapped to the capability, opportunity, motivation, behaviour model (COM-B) and behaviour change wheel (BCW) to inform future implementation recommendations.

Results

Prominent barriers influencing the clinical uptake of COPD guidelines were identified using TDF analysis and included knowledge, professional role clarity, clinical behaviour regulation, memory, attention, and decision process, beliefs about departmental capabilities, environmental context and resources. Potential interventions included education, training, staffing, funding and time-efficient digitalised referrals and systems management reminders to prevent COPD readmissions, remissions and improve patient health-related quality of life.

Conclusion

Implementation strategies such as electronic interdisciplinary COPD proforma that facilitates a multimodal approach with appropriate patient/staff resources and referrals prior to discharge from an ED require further exploration. Greater clarity around which components of the COPD X guidelines must be applied in ED settings needs to stem from future research.

Keywords: AECOPD management, COPD guidelines adherence, theoretical domains framework, multidisciplinary, COM-B, behaviour change wheel, behaviour change techniques taxonomy

Introduction

COPD guideline non-adherence in clinical practice is a significant problem well recognised and reported in national and international literature.1–3 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) kills more than 3 million people worldwide every year and affects around 174 million people globally.4 The World Health Organization predicts COPD to become the third leading cause of death by 2030 considering its increase in prevalence and morbidity. Complex chronic disease management processes need to be examined further to meet unmet patient and carer needs in the community with a focus on health-related quality of life. Non-pharmacological programmes inclusive of pulmonary rehabilitation, smoking cessation programmes, increasing physical activity, and early detection and treatment of comorbidities are reiterated as key components to reduce the burden of the disease.4,5 Current holistic national guidelines originally published in 2003 in Australia known as COPD-X Plan are not adhered to consistently by doctors, nurses and interdisciplinary health professionals.3 Pharmacological interventions are well explored and reported compared to non-pharmacological interventions in relation to adherence rates.3 National guidelines (COPD-X plan) and international guidelines (Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease [GOLD]) have consistently pointed towards the importance of non-pharmacological interventions to assist patients with self-management and community management to prevent readmissions and acute exacerbations.5,6 In 2008, estimated costs for COPD care in Australia were AUD $8.8 billion in primary and tertiary hospitals, with AUD $89 billion spent on COPD-related disability and premature death.7,8 The Australian National Morbidity Database reveals that in 2017–2018, there were 77,660 hospitalisations of people above 45 and over, and the rate of hospitalisation was 732 per 100,000 population.8,9

A significant variation in clinical practice was reported through a cohort study conducted in 46 EDs in Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Hong Kong and Malaysia that aimed to explore epidemiology, clinical features, treatment outcomes, hospital length of stay and in-hospital mortality.10 The findings revealed that most acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) patients arriving in EDs by ambulance had increased hospitalisation and significant in-hospital mortality.10 A planned sub-study of Australia, Asia, New Zealand dyspnoea in emergency departments (AANZDEM) concluded compliance with COPD evidence-based guidelines is suboptimal in EDs and suggested further research to improve compliance with guidelines and consideration for implementation strategies.3 Economic research data in three Southern Queensland Hospitals reveal a total health service cost of AUD $ 42, 142, 474 for COPD ED presentations across all 3 sites where 41.1% of presentations were assessed as emergency triage category 3 or 4 in the EDs and were transferred home on the same day.11,12 The Australian triage scale outlines five categories from Category-1, an immediately life-threatening condition involving prompt assessment and treatment to Category-5, a chronic or minor condition to be assessed and treated within 2 hours.13 The estimated cost savings of reduced COPD-related admission is around AUD $533 per patient in these ED’s. These economic research data further report that 50% of COPD presentations were discharged within 4 hours without a targeted referral. Implications of this practice often lead to repetitive readmissions of COPD exacerbations, increased economic burden, and poor optimisation of patient lung function and overall health.11,12,14,15

Sub-optimal dissemination and implementation of guidelines can significantly impede adoption into daily practice.16 Local, national, and international respiratory societies are seeking better implementation strategies for the uptake of COPD guidelines,5 particularly since pharmacological interventions and invasive ventilation support practices have drifted from evidence-based guidelines.3,17,18 A Canadian retrospective study of COPD readmissions discharged from ED reported a significantly higher risk of readmission due to variability in treatment.19,20 The findings indicate less than 50% of COPD patients presenting to the ED received recommended COPD therapy.19 A COCHRANE systematic review on integrated disease management programs reported improved disease-related quality of life, increased exercise capacity, reduced hospital admissions and hospital days per person.20 Future implementation research should consider barriers and facilitators to inform change management and compliance indicators among hospital stakeholders.

COPD-X plan entails advances in the management of COPD that are updated quarterly in the national COPD guidelines (COPD-X plan) by Lung Foundation Australia in conjunction with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand.5 This guideline comprises evidence-based recommendations to interdisciplinary health care professionals to assist with case identification and diagnosis, optimise patient function, prevent deterioration, develop support network and self-management plan to avoid future exacerbations.5 COPD guideline non-adherence is a well-studied and reported phenomenon albeit no studies have to date explored barriers and potential solutions from an interdisciplinary staff perspective. This study aimed to investigate the barriers and enablers that influence the uptake of COPD-X plan guidelines amongst interdisciplinary staff in the emergency department. The premise of the study was to determine elements of the COPD guidelines that are adhered to by interdisciplinary health professionals and explore potential solutions to mitigate guideline non-adherence.

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) has been utilised in this research as an overarching framework that integrates a range of behaviour change theories. In similar research designs, it has been used to examine barriers and uptake of evidence in a variety of clinical settings.21 The framework includes 14 domains: 1) knowledge, 2) skills, 3) beliefs about capabilities, 4) memory, attention, and decision processes, 5) behavioural regulation, 6) environmental context and resources, 7) social influences, 8) intentions, 9) social/professional role and identity, 10) beliefs about consequences, 11), reinforcement, 12) emotion, 13) optimism, and 14) goals.21 Capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour model (COM-B) recognises behaviour as part of an interacting interconnected system where planned interventions need to address one or all of them to achieve optimum implementation.22 Behaviour change wheel (BCW) originally developed from a systematic review analysing 19 frameworks of behaviour change methods consists of three layers.22 Central hub incorporates sources of behaviour to assist with the diagnosis of implementation barriers (capability [physical, psychological], opportunity [physical, reflective], motivation [psychological, automatic]), whereas the middle layer comprehends choices of nine intervention functions compatible to COM-B diagnosis of barriers (Education, Persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, training, enablement, modelling, environmental restructuring and restrictions).22 The outer layer of the wheel identifies seven policy categories to support the implementation of the chosen interventions (Guidelines, Environmental/social planning, Communication/Marketing, Legislation, Service provision, Regulation, Fiscal measures).22 This approach provides a means to prioritise implementation strategies and target determinants of individual, professional or organisational behaviour and practice.

Methods

A qualitative interpretive study design employing semi-structured individual interviews with questions stemming from a preliminary literature review was used to explore enablers and barriers that influence COPD management in interdisciplinary teams in the ED. In addition, reflexive thematic analysis was applied with the TDF and COM-B model to assist in the development of potential intervention strategies to improve COPD guideline adherence.

Setting, Sample, and Recruitment

Eight participants (2 doctors, 2 nurses, 2 physiotherapists, 1 pharmacist, and 1 social worker) were recruited from a metropolitan, tertiary hospital in Queensland, Australia. The participants were derived from a convenience sample of interdisciplinary staff (doctors, nurses, allied health) that were invited to participate via email. The research was advertised via flyers placed in the local ED. Written and signed informed consent was sought from individuals participating in the research. Ethics approval was obtained, prior to commencement, from the Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC EC00168/55098), and administrative approval was gained from the University Human Research Ethics Committee (H19REA308).

Data Collection

Individual semi-structured interviews of 20–50 minutes duration were conducted in the ED in a quiet room to ensure privacy. Questions included participant’s experience, perceptions and solutions to current perceived barriers towards COPD-X guidelines non-adherence in the ED (see Table 1). Data saturation was assessed once no new information emerged at which point data collection ceased. Digitally recorded interviews were later de-identified and transcribed verbatim. Demographic data, including position, gender and, years of experience, were collected as part of the interview process.

Table 1.

Interview Questions Designed to Create Discussion and Share Experiences

| Interview Questions | Purpose of Question and Supporting Literature |

|---|---|

|

Role clarification, decreased awareness and lack of familiarity are some reasons for suboptimal COPD treatment16,23 |

|

Lack of integrated care affects health related quality of life (Hrqol) of COPD patients24,25 |

|

Publication of guidelines has not achieved optimal COPD treatment, hence exploring barriers to adherence needs emphasis in future research16,26 |

|

Explore probable solutions such as having guidelines and cues accessible at point of care may improve concordance16,26 |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; AECOPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Data Analysis

The TDF, as part of the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW), has previously guided a process for developing interventions and policy that specifically target deficits in three identified essential behaviour change conditions: capability, opportunity, and motivation (referred to as the COM-B system).21 Researchers have utilised the BCW to develop potential interventions to improve the utilisation and implementation of health guidelines. This taxonomy has been proven and applied to inform the development of interventions and policies to improve the delivery of healthcare in a variety of clinical settings including stroke and perioperative clinical guidelines adherence.27–29 The TDF and COM-B model assisted this research team in providing a systematic approach to data analysis that enabled the team to prioritise and develop implementation strategies that specifically target clinician-identified deficits and address barriers and enablers that influence the uptake of the clinical guidelines.

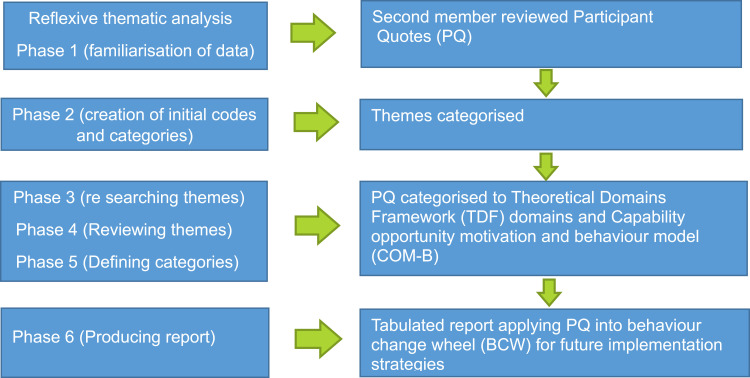

Six steps of reflexive thematic analysis as outlined by Braun & Clark (2006) were mapped against 14 domains of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Phase 1 included familiarisation of data and Phase 2 had two independent members of team review the data. The final stage of Phase 2 included the identification of initial codes. Phase 3, 4, 5 of thematic analysis was utilized to generate belief statements across the domains analysed, categorised and the textual data were assigned into the 14 TDF domains (see Figure 1). The coding strategy was reviewed and the consensus was established in the research team before applying the same principles to the remaining data. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion in the research team. Identified domains affecting clinical behaviour and non-adherence to guidelines were mapped to the capability (C), opportunity (O), and motivation (M) components, which form the behaviour change wheel. Sub-components of COM-B were merged with individual BCT techniques and participant implementation suggestions for their department to achieve better adherence.

Figure 1.

Data analysis graphic representation. Notes: Research design stages utilising reflexive thematic analysis (data from Braune & Clarke37) merged with theoretical domains framework (TDF) and Capability, Opportunity, Motivation- behaviour change wheel (COM-B, BCW) (data from Michie et al38).

Results

Results are depicted in tables under each domain with participant quotes linking the 14 TDF domains to identified barriers in the use of the COPD X guideline. All illustrative quotes were matched with COM-B behaviour change wheel components and participants' implementation suggestions for better uptake of guidelines. Frequency scores were given to each domain to understand the prominence of the barriers and frequency of beliefs among participants.21,30 The reflexive thematic analysis identified seven theoretical domains as most relevant (frequency score 4 and above) to the clinical uptake for COPD X guidelines in the emergency department. Improving adherence to the guidelines was highly dependent on the identified domains and recommended interventions and implementation strategies from participants. Each of the most relevant domains identified is represented in the analysis. Eight domains emerged with the most prominent themes including knowledge, skills, beliefs about capabilities, memory/attention/decision process, behaviour regulation, environmental context and resources, social/professional role/identity and emotion. This was in parallel to six less relevant meta-themes representing beliefs about consequences, optimism, reinforcement, intentions, goals and social influences.

Domain 1 (Knowledge)

Lack of awareness of guidelines and a lack of focussed respiratory management pre-eminently associated with COPD management were identified as a major barrier to the formation of knowledge and subsequent utilisation of the guidelines. Participants expressed a lack of awareness of the guidelines and declared they had never accessed them. Clinicians expressed their awareness of international guidelines and the need to utilise them, however, existence, awareness and utilisation of Australian National COPD-X guidelines in the clinical area existed to be a source of confusion for some clinicians. Participants stated if they were aware of community services or how and where to refer, they would action these referrals. Lack of education and in-services on the guidelines and management of COPD patients were expressed as a cause of non-adherence by most participants in the emergency department. Several participants noted that it was difficult to grow knowledge around COPD guidelines as the systems access or online availability of resources was quite poor. Participants believed continuing education with respiratory focus, through in-service and awareness programmes to point towards existing community services would augment staff awareness, utilisation and adherence. A complete summary of staff perspectives and the recommended evidenced based implementation strategies from BCT and participants for the TDF domain 1, knowledge is identified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Implementation Strategies from BCW and Participants for TDF Domain 1: Knowledge

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency Score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Participants Recommended Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of awareness of guidelines Lack of awareness of respiratory management for ED Lack of education or in services sessions |

6 | P1. Physio.1: -“I am Vaguely aware of the guidelines being a musculoskeletal physiotherapy expert. COPD Awareness Week might be something that you can do like Falls Prevention Month, which is like a whole month of awareness events” P2. Physio.2:-“there is literally no respiratory focus in our competency in ED, so we are just taking whatever knowledge that we’ve got from our degrees and from our previous work” P3. Nurse.1:-“Probably for nurses, it’s just not having the ongoing education is a barrier, like who to refer to, how to refer to them, having someone based in the Department would be helpful because that would break down the barrier of not being able to find them” P6. Doctor.1:-“Doctors through their medical training would have looked closely at the COPD Guidelines, so I can speak for that. I’m not sure about nursing staff and other allied health staff” P7. Pharmacist: - “ If we had knowledge and access of available Community services, we could provide the patient with that sort of information” P8. Doctor.2: -“Hospital intranet has access to a multitude of different Guidelines. Frankly I don’t see any of us using any of that. We tend to use the Australian Therapeutic Guidelines for right course of therapy” |

Capability Psychological Physical |

Training Modelling Enablement |

In services training (P1, P4) Education on guidelines (P2, P3,P4) Provision of resources and readily access in clinical practice(P7) |

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel.

Domain 2 (Skills)

Emergency department staff consult diverse disease conditions and as a result upskilling according to all specialities can be challenging. Participants reported lacking skills and experience in respiratory management and patient education skills that have affected their capacity to implement the guidelines in clinical practice. Current in-service educational sessions for the Emergency Department staff are not targeted to training particularly with respiratory disease management skills. It was noted that some staff bring years of expertise working in different clinical areas prior to working in ED. Physiotherapists who had more experience working in the ED stated that their skills and knowledge are mostly in musculoskeletal therapy and there is no staff from their department who are focussed on respiratory conditions in the ED. Nurses noted that they are often teaching patients on inhaler technique however are not trained themselves on the best techniques or specific detail outlined in the COPD-X guidelines. Clinicians who had more knowledge of disease condition and preventative measures of COPD had acquired skills during their undergraduate medical training, conferences, or working in respiratory wards previous to commencing in the ED. Three participants reported ongoing educational sessions on COPD management, preventative and restorative health and appropriate referrals are inevitable as they have multiple specialities to accommodate when working in an ED. A comprehensive summary of participant perspectives on lack of respiratory management skills is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Implementation Strategies from BCW and Participants for TDF Domain 2: Skills

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency Score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Participants Recommended Implementation Strategies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current job skills or roles are not respiratory management oriented Lacking skills and experience to provide patient education |

4 | P1. Physio.1:-“I’m here as a Musculo-skeletal expert, from time to time we might answer some questions from doctors about respiratory physiotherapy management, but we’re not involved in directly managing the patients in the emergency department” P2. Physio.2:- “Experience managing COPD patients in the ED is very little. We don’t directly treat COPD patients in the Emergency Department” P4. Nurse.2:-“Usually the nurses do patient education and we’re currently using spacers at the moment for teaching inhaler technique. We are never given any training around this in the department. We don’t have any specific COPD management In-services or education especially in winter which precipitates their symptoms” P8. Doctor.2: - “I don’t see Respiratory Specialty Nursing or Allied health, specifically being utilised in the Emergency Department” |

Capability Physical |

Training modelling |

Education/In-services (P4) Resources for self-directed study(P2) ED champions to lead educational sessions (P8) |

|

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel.

Domain 3 (Beliefs About Capabilities)

Reality or validity regarding the ability to adhere to COPD-X guidelines in the emergency department is explored in this domain. Table 4 outlines the beliefs about the capabilities of the participants interviewed. Interdisciplinary staff disclosed a lack of confidence in managing and discharging COPD patients. Most participants expressed that due to the nature, busy pace and time constraints in EDs are not feasible to provide care more than the acute emergent needs of the patient. National emergency access target (4 hours in ED) rule emphasise the requirement of discharging a patient from ED to make space available for upcoming acute patients which results in a higher turnover of patients, increased pressure and demand on staff. Participants believed the challenging and unprecedented nature of the emergency department with high acuity patients, and life-threatening conditions diminish their capability to provide care more than acute emergent needs of the patient. The participants revealed that time constraints and the volume of patients impact the capabilities of staff to provide accurate discharge planning or referrals as per guideline recommendations, such as vaccination, smoking cessation and other non-acute guideline-recommended interventions. Participants are certain that time-efficient assessment and referral processes could prevent fragmented care and COPD remissions or related readmissions. Although participants agreed on a current lack of capacity to provide discharge planning and referrals, it was evident from their responses that easily accessible patient information for packages for smoking cessation and easier electronic referrals to the community from ED could prevent COPD readmissions.

Table 4.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Implementation Strategies from BCW and Participants for TDF Domain 3: Beliefs and Capabilities

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency Score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Participants Recommended Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence in COPD management Nature and pace of emergency departments makes it impossible to provide care more than acute emergent needs of the patient Time constraints impact capabilities to provide care |

5 | P1. Physio.1: -“We certainly have community services available which we could refer before discharge from Ed, Respiratory care is within their scope of practice for those community-based physios, I’m not sure about that. I’ll need to find out” P1. Physio.1:-“As we have a specific National emergency access target (NEAT) to meet and the Emergency Department is probably not the ideal place or the expertise to optimise their care” P8. Doctor.2:-“We discharge the patient back to Primary Care, we frankly don’t know what is happening to the patient in terms of Physiotherapy and pulmonary rehabilitation and we could potentially help direct some care. But I think in terms of developing processes, I see that that in itself is a little bit of a barrier to care” P8. Doctor.2: -“we are pressured for time due to NEAT targets (4 hours in Ed), providing the full gamut or array of multi-disciplinary care within ED is difficult. Priority would be to ensure that they are not in acute respiratory failure and then hand over to the Respiratory Medical Team/primary care for their further cares” P8. Doctor.2: -“The utilisation of opportunistic vaccination in the Emergency Department is a good public health initiative, but it is completely impractical in the context of an Emergency Department. We may be able to do that, but one fails to see that there is time that is consumed in these actions and the question is who is missing out on Emergency Care” P5.Social worker:- “ often it takes longer than four hours to provide social work input so if I am not able to get someone reviewed by four hours, I think “Ok, I’ve gone over the four hours so send it straight out to the Community” P6.Doctor.1:-“Volume of patients that we have is a major barrier as you’re rapidly trying to get through a huge amount of different patients at the same time as trying not to miss serious things, but then trying to assess people and discharge people who don’t need admission” P7. Pharmacist:- Smoking cessation will get asked as part of the medical review but it will probably be something like “well, you know, if you cut down, your symptoms will be better” but that’s probably the extent of it (P7) |

Motivation Reflective |

Environmental restructuring Education |

Provide information or accessible resources in workplace on how to make community referrals (P1) Electronic referrals provides time efficient care in the Emergency department (P7,P8) Easily accessible packages for smoking cessation assistance during admission (P7) Research and implement less time consuming processes for facilitating referral and management in the Emergency Department (P1, P8) Direct community referrals by ED admin (P8) |

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel; NEAT, national emergency access target.

Domain 4 (Memory Attention and Decision Process)

Ability to retain information from guidelines is compromised periodically as participants are required to deal with a multitude of life-threatening conditions from different specialities of medicine at any point in time within a single shift. Thus, participants discussed that recalling all management, recommendations and treatment modalities from COPD guidelines can be difficult. It was clear that participants preferred speciality based review from a respiratory clinical nurse consultant in the first instance to facilitate appropriate care prior to discharge from ED. Multiple staff reiterated the need for point of care clinical cues, prompts, checklist and easier access to resources including patient information as a probable solution to better adherence to COPD guidelines. A sense of optimism existed between staff as they expressed that if they had the resources and timely access to utilise knowledge with accurate digital instructions, then guideline adherence is likely to improve. Table 5 shares quotes and implementation strategies relating to memory attention and decision processes by staff caring for COPD patients in the ED.

Table 5.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Implementation Strategies from BCW and Participants for TDF Domain 4: Memory Attention and Decision Process

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency Score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Participants Recommended Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty recalling all treatment and management modality from COPD guidelines | 3 | P3.Nurse.1:-“Respiratory clinical nurse consultants (CNC) won’t always come through Emergency and if it’s someone who’s going home, they’re probably seen as not that critical and I’m not sure how often they would be able to come or be willing to come down to Emergency. Having a deck phone, we could ring to actually talk to a respiratory expert, someone would be a big help, and if we knew that the resource was there, we would use it” P3. Nurse.1: - “We have multitude of different guidelines, which itself can be confusing” P7. Pharmacist: -“Twenty other people wait outside that can’t stay for someone to make a phone call for them unfortunately so direct, non-time consuming digital referrals will help” P8. Doctor.1:-“Dealing with multiple disciplines and speciality cases my primary complaint at the moment would be that we used to have ‘UptoDate’ database access for international guidelines in electronic form for quick reference. We no longer have it. It is unreasonable to expect ED staff to provide discipline-based discharge” |

Capability Psychological physical |

Modelling Environmental re-structuring Education Enablement |

Availability of respiratory nurse specialist for advice and review in ED patients (P3) Electronic resources access to international and national guidelines (P8) Adding prompts and cues to clinical area (p3) COPD discharge template (P8) |

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel.

Domain 5 (Behavioural Regulation)

Clinical behaviour measured objectively that is capable of affecting COPD-X plan guideline adherence is discussed in this domain. Participants indicated that interdisciplinary staff often fail to abide by the current corporate governance, services and management. Common themes emerged through the experience of participants for areas of quality improvement including: anxiety, smoking cessation, palliative care, opportunistic vaccination, inhaler compliance and pulmonary rehabilitation referrals. Participants expressed that each of these areas could be improved and the social worker indicated that they are hardly involved in the emergency department patient referral process prior to discharge. To a certain degree, all staff agreed with better systems and change management with appropriate implementation strategies this may be rectified. The participants expressed areas where improvements could occur. These areas supported by the experiences of participants suggested having ED respiratory change champions, better technology to provide ED to community referrals and COPD discharge templates that could be utilised to assist staff to screen and refer in the ED as per the COPD guidelines. The specific quotes and implementation strategies are outlined in Table 6.

Table 6.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Implementation Strategies from BCW and Participants for TDF Domain 5: Behavioural Regulation

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency Score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Participants Recommended Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failure to abide COPD guidelines or related quality initiative available in ED | 7 | P1. Physio.1: - “Pulmonary rehabilitation I’m not aware of that practice in ED, mostly done by respiratory physios in the respiratory ward” P2. Physio.2: -“We have a pulmonary rehab service that we can refer to from ED and then we have other general rehab services like we have Day Therapy that we could use but currently not so much” P2. Physio.2: -“Community/Respiratory ward physio referrals from Ed can be done, maybe have a phone discussion with the ward physio to do the community referral. Not a huge time commitment” P2. Physio.2: “There have been a couple of patients, who have potentially been frail, discharged home and then have re-presented with another fall or not coping at home and then have had MDT input or an admission and MDT input to optimise them at home. Yeah, that’s certainly happened multiple times” P3. Nurse.1: - “Lack of addressing anxiety is a reason for failed discharges. They’re not coping at home. That’s probably the biggest one” P5. Social worker: - “Medical teams don’t ask that question about anxiety may cause some readmissions” P6. Doctor.1:-“we do not do community or pulmonary rehabilitation referrals and all of those kinds of things is a barrier, because I think that is one of the things that does slip through the cracks” P6. Doctor.1: -“ED is certainly capable of giving pulmonary rehabilitation referrals but I haven’t myself or seen anybody do that. We would more expect patients who go to the Respiratory Ward can get it there” P7.Pharmacist:-“It would benefit if our doctors write into the discharge letter to the GP, ‘please ask for a Home Medicine Review’ If we make the call as a Pharmacist that we want their inhaler technique checked at home or their medicines checked” P8. Doctor.2: -“We do not provide the opportunistic vaccination to patients whilst they are in ED partially because it is public health responsibility and by utilising staff time we lose time to provide acute emergent care for other patients” P7. Pharmacist: -“Inhaler compliance thing really, that is the problem most of the time for readmissions. You know, there’s the smoke in the air that brings them in and then there’s flu season that brings them in but a lot of the time the only thing that can actually be fixed is probably like, lifestyle and inhaler compliance” |

Capability Psychological physical |

Modelling Enablement |

Respiratory management champions in ED to model, educate and lead (P8) Easier referrals using electronic systems and telecommunications technology (p6) Direct community referrals to GP for patients discharged from ED (P7,P1,P8,P6) COPD discharge templates for ED (P8) Vaccination and inhaler technique education referrals to primary care or resources in ED linked through respiratory department (P6, P7, P8) Patients coping mechanisms, anxiety and triggers to be screened and referred to appropriate services (P3, P5) |

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel; GP, general practitioner; MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Domain 6 (Environmental Context and Resources)

The environmental context and resources domain confer circumstances and situations that discourage guideline adherence. This domain had the highest frequency of themes comprising funding, staffing, inability to communicate, lack of equipment and lack of appropriate referral systems. Participants outlined the need for more resources during the winter months. Throughout this time frame participants identified periods that required more respiratory staffing and funding allocated to meet the higher patient demands in respiratory presentations. Participants repeatedly stated if psychology team and occupational therapist are employed to an ED team, they would be able to assist with better management of COPD patients in terms of anxiety and acopia management strategies. Participants commented that equipment such as spirometry and other pulmonary function tests are not readily available and are dismissed as the job of respiratory specialty rather than ED staff. In addition, it was evident from participant statements that care requirements including vaccinations, smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation referrals were not provided to patients on discharge. Participants outlined that current barriers hindering appropriate interdisciplinary referrals included the lack of environmental resources such as technology being unavailable to enable direct referrals to respiratory outpatient clinics or directly to community services. Three participants expressed restructuring of care processes with direct respiratory clinic referral processes, a respiratory nurse review in ED and electronic concise interdisciplinary COPD guidelines for ED management will assist better utilisation of guidelines. Participants identified that these initiatives could assist in the promotion of COPD guideline adherence in the ED. The barriers and implementation strategies recommended by participants are outlined in Table 7.

Table 7.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Implementation Strategies from BCW and Participants for TDF Domain 6: Environmental Context and Resources

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Participants Recommended Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of human resources affect adherence to guideline Lack of monetary funding affects guideline adherence lack of equipment is a barrier to guideline adherence Lack of interdisciplinary communication means |

8 | P1.physio.1:-“Physiotherapy Department as a whole in the hospital employ more physios during the winter peak because we have more presentations of respiratory infections in the COPD population we have no respiratory physios in ED, current workload is just not sustainable” P1.physio.1:-“occupational therapists that work in the Respiratory Wards are also the ones that come to the pulmonary rehabilitation sessions teach the patients on pacing, activity modification, relaxation and I guess also functional things using appropriate furniture or tools. Patients discharged from ED; can they be seen in clinics is another question for multidisciplinary input” P1. Physio.1: - “For special patient populations in the ED a resource area champion could be useful and I use the example of geriatric emergency medicine” P2. physio.2:-“There is next to no occupational therapist (OT) input in Emergency apart from the Allied Health Practitioner in older person’s assessment and Liaison services. I guess funding, space, skill set is a barrier” P3. Nurse.1:- “Smoking cessation, probably not in Emergency as you would say you shouldn’t still be smoking”, but that’s it. That’s the end of the discussion not offering any support. we do not actually give them any Community referrals” We just do not do that well in Ed when we have the opportunity” P3. Nurse.1:- “if we had Clinicians who were Allied Health Practitioners for COPD management/respiratory ‘stuff’ we would be quick to refer to them” P4. Nurse.2: - “Incase family is there and the patient is actively dying from this illness, social worker is involved. we don’t get OT’s involved down here or communicate with palliative care” P5. Social worker: - “They don’t provide Psychology support in ED from a mental health perspective” P6. Doctor.1: -“Doctors potentially ask for inhaler technique education if that’s been flagged as an issue. Patients say they take puffers but we can’t figure out what ones they are and Pharmacy might call the GP and do some more digging around and ask what kind of medications they do take. Time becomes a barrier in ED” P7. Pharmacist: -“Due to workload and the bed situation, we can’t kind of have people in just for a vaccination. Upskilling our doctors and nurses on COPD management will compete with so many other priorities. Resourcing with respiratory staff will help” P7. Pharmacist: -“if there was a way to refer to Respiratory Outpatients Clinics straight from EDIS (ED referral system), which would probably be useful if you thought someone needed follow up but not today. We have our electronic Emergency Department referral system (EDIS) where staff would click on ‘refer to Respiratory Registrar’ when they do it, that doesn’t go anywhere. That’s just for our record that we called them, so it wouldn’t be phone call which is a barrier” P7. Pharmacist: -“We don’t have enough Pharmacists or registrars or consultants to see every respiratory patient in ED. Respiratory nurses should come and see every patient. Automatic referrals might come in handy her too” |

Opportunity Physical |

Environmental restructuring Persuasion Incentivisation |

Enabling interdisciplinary communication (P2) Prompts and clue for care and referrals (P6, P7) Funding resources (P7,P1) Staffing resources including department resource champions (P3, P1,P7) Providing appropriate equipment (P2, P5,P1) Automatic referrals and direct community referrals (pulmonary rehab) (P7) Restructuring processes of care (Respiratory clinic referral, respiratory nurse review in ED) (P1,P7) Electronic concise COPD guidelines for ED (P8, P3) |

|

P7. Pharmacist: -“Twenty other people wait outside that can’t stay for someone to make a phone call for them unfortunately so direct, non-time consuming digital referrals will help” P8. Doctor.2: -“Equipment aspects of barrier we do not provide this cohort of patient a Spirometry or any Pulmonary function testing, it may not be appropriate in acute exacerbations anyway” P8. Doctor.2: -“Sometimes the patient has left without the discharge letter for some reason, in which case our Admin officers then fax the letter, diligently, to the patient’s GP, some Guidelines could be sent this way too” |

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel; GP, general practitioner.

Domain 7 (Social Professional Role Identity)

Coherent set of clinical behaviours influenced by the social and professional role identity of interdisciplinary staff is elucidated in this domain (Table 8). Participants identified their professional standing in the interviews and each expressed a clear understanding of their role and scope of practice in the ED. They identified professional boundaries and lack of role clarification in managing COPD patients and lack of communication amongst staff had affected the uptake of guideline adherence. Participants stated they were confused regarding referrals for COPD patients particularly in regard to needing more clarity, access or guidance around interdisciplinary professional roles relating to the COPD guidelines. In addition, they felt that these areas inevitably contributed to guideline adherence in the ED. Role clarification and lack of systems referral processes remain a barrier to provide appropriate care to COPD patients in the ED.

Table 8.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Evidenced Based Implementation Strategies from BCT and Participants for TDF Domain 7: Social Professional Role Identity

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency Score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Participants Recommended Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional boundaries and roles are affecting guideline adherence | 5 | P1. Physio.1:- “We don’t routinely get referred to respiratory patients as my role in Ed is not that often as a general physiotherapist. I’m here as a Musculo-skeletal expert” P1.Physio.1:- “I have received a call from one of our doctors saying “can we do a six-minute walk test in the ED to see if this patient de-saturates on room air” and I said to them,“I haven’t worked in COPD care for a long time but we used to do that, but we don’t do that anymore. We do arterial blood gas (ABG) instead” P2. Physio.2: - “I don’t get any respiratory referrals for COPD patients in ED being a musculoskeletal expert” P3. Nurse.1: -“We have Physios for Fast Track area and we have the OT in OPALS but they are for older people, like their catchment is 70 years and older. There’s social worker which is obviously for everyone but there’s no-one else really in the Emergency Department for patients discharged from ED” P5. Social worker: - “Doctors and nurses during their assessment should be asking something in relation to emotional status. So they are asking about home – “do you live on your own, do you live with somebody, do you have any community supports” and then “emotionally how are you managing your COPD diagnosis” P7. Pharmacist: - “Respiratory CNC won’t always come through to ED” |

Opportunity Social |

Environmental restructuring Education Persuasion |

ED champions to promote and monitor referral pathways (P1) Encourage doctors and nurses to ask emotional status during history collection (P5) |

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel; GP, general practitioner; MDT, multidisciplinary team; OPALS, older person assessment and liaison service; CNC, clinical nurse consultant.

Domain 8 (Emotion)

Personal belief, attitude and nihilistic views of treating staff towards guideline adherence and related quality initiative, acting as a barrier towards ED COPD holistic management will be construed in this domain. A layer of confusion existed as participants expressed concerns about referrals of COPD patients in the ED. Participants expressed a general perception or attitude with staff viewing non-acute care patients to be beyond their responsibility. Non-acute patients tended to be discharged from ED without appropriate follow-up and participants disclosed concern that for some patients presenting to the ED, this results in increasing COPD remissions and readmissions. In addition, participants repeatedly stated due to different professions and specialities involved in the Emergency Department in terms of setting and treating patients this perception leads to poor interdisciplinary communication with referrals and patient management. Participants outlined that the primary care team specialising in patients within the realm of Chronic Obstructive Airways Disease should be held responsible for non-adherence. Table 9 identifies the emotional barriers to adherence and the strategies identified by participants of this study to improve practice and compliance with COPD guidelines by staff in the ED. These strategies included better communication, delegation and planning between specialty departments interdisciplinary staff may assist in mitigating this attitude amongst staff.

Table 9.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Implementation Strategies from BCW and Participants for TDF Domain 8: Emotion

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency Score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Participants Recommended Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception and views of treating staff | 3 | P1. Physio.1:-“Different professions are involved in the Emergency Department in terms of setting and treating patients with respiratory problems or respiratory side of Physiotherapy is probably not part of my scope and agenda as musculoskeletal physio” P8. Doctor.2: - “It is unreasonable to expect ED staff to provide discipline based discharge” P4. Nurse.2: -“We usually approach our doctors for specific case knowledge of COPD. We don’t refer to our Guidelines. I think it is probably changing, but nurses probably think we’ll just do what the doctor told us to do rather than suggesting stuff ourselves” P8. Doctor.2;- “The context in which the patient is cared for, in other words in an Emergency Department, in itself has got some limitations as to how we are going to go about diagnosing, treating and following up or helping to follow up these patients. it is the immediate problem that we are going to be attending to and we are not going to be providing the service of follow up care because that’s in the hands of the General Practitioner or the other sub-Specialty such as Respiratory Medicine, So I think that in itself, sort of inherently limits the scope of care that we provide. Number one is I would say, we can do change management better. there is very little thought put into the time it will take a Practitioner to actually deploy the service and if it does take time, what is the opportunity cost of that time and I do not ever see this being debated’ |

Motivation Reflective Automatic |

Coercion Education |

Reassure staff with education (P1) Automatic easier referrals through current software such as EDIS (P7) Prompts and clues including discharge templates for all COPD patients (P8) |

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel.

Less Relevant Domains

Six Domains were considered less relevant due to their lower frequency scores of below 3 which included domains surrounding beliefs about consequences, reinforcement, optimism, intention, social influences and goals (see Table 10). Two participants expressed the consequences of performing multidisciplinary care in ED is the verity that other patients may be compromised with acute emergent care needs (beliefs of consequences). Several participants thought automation and technological advancement with clinical cues and prompts in the ED could be beneficial to COPD guideline usage and compliance. Participants recommended utilising an interdisciplinary checklist, e-resources and patient community services information packages to assist with reinforcing interdisciplinary staff behaviour to enable COPD guideline adherence (Reinforcement). Multiple participants revealed having resource champions in the respiratory area and interested senior staff engagement in evaluation methods and leadership is anticipated and proven to increase interdisciplinary guideline adherence (Reinforcement). Participants believed that time-efficient systems for clinicians and interdisciplinary staff knowledge enhancement practices will improve guideline adherence (optimism). Participants felt positive in involving community services as it was deemed a usual referral in the prevention of COPD-related remissions and readmissions to ED (optimism). Participants stated they intend to provide guidance to the primary care physician with discharge letters to ensure appropriate services are facilitated in the community to assist COPD patients with better health-related quality of life (Intention). Further, they identified that communication between staff is pivotal to reduce inpatient admission, timely discharges, prevent remissions and readmissions to ED (social influences). Participants have not identified any barriers with their goals (domain.14) towards guideline adherence in this study.

Table 10.

Identified Barriers Mapped to COM-B Model and Recommended Implementation Strategies from BCW and Participants for Domains 9,10, 11,12,13 (Beliefs About Consequences, Reinforcement, Optimism, Intention, Social Influences)

| Guideline Uptake Barrier | Frequency Score/8 | Participant Quotation (Barriers) | COM-B Components | Recommended Intervention (BCW) | Implementation Strategies from Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain.9 (Belief about consequences) Adverse health outcomes due to COPD guidelines adherence in ED |

2 | P7. Pharmacist: -“We get referrals where we can’t necessarily see everyone, so we’ve got to decide who the highest risk is and who we’re going to see. You can’t take up an Emergency bed to wait for a Pharmacist to arrive” P1. Physio.1:- “I would suspect if they will follow up with their GP within 24 to 48 hours to make sure that they are not deteriorating and I suspect that they are routinely followed up within the Respiratory team as well in the Outpatients Clinic in |

Motivation Reflective |

Education Environmental restructuring |

Refer or arrange community pharmacist review (P7) Direct referrals to respiratory outpatient clinic for interdisciplinary input (smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, inhaler technique education) (P1, P7) |

| Domain.10 (Reinforcement) Reinforcing Clinician and interdisciplinary staff knowledge utilization and resource provision will improve guideline adherence |

3 | P1. Physio.1: -“COPD primary core practice nurse coming in and doing In-services and education training, easily accessible information, tool kits that are available on the Intranet”. P2. Physio.2:-“Providing information on who to refer to, how to refer to them, having someone based in the Department would be awesome, because that would break down the barrier of not being able to find them or they work ‘these’ hours and you don’t know where they are” P3. Nurse.1: - “Inhaler technique, we don’t give education to carers and family members who might be helping them at home, using their inhalers so that’s a huge barrier” P1. Physio.1- “consultants within ED or staff who are here more on the longer term could be involved in projects about COPD so that they are championing the cause” |

Motivation Automatic |

Education coercion |

Education/in-service by ED and Thoracic respiratory department to increase utilisation (P1) Automatic referrals and documentation of the same during clinical care (P2) Pharmacy department to initiate inhaler technique educational sessions for staff (P3, P7) Automatic referrals to community for allied health input (P1, P7,P8) |

| Domain.11 (Optimism) Clinician and interdisciplinary staff attitude about COPD guideline adherence |

3 | P1. Physio.1: -“It might be possible with education awareness and perhaps – I know that there is a respiratory resource nurse or, someone like that who can be aware of the COPD patients coming to the hospital, coming through the ED and sort of making sure that these patients are getting those guidelines met” P4. Nurse.2: - -“There is a potential if patient getting discharged from ED to continue that multi-disciplinary care, exploring with the current network or service model. We’ve got an inpatient medical team with the multi-disciplinary support and how can that be expanded into the ED or community like hospital to home programme” P2. Physio.2:-“Community health staff provide antibiotics, nursing care and physiotherapy inputted into their care. So that will probably be the sort of expansion of the service that I can foresee happening. Would this also reduce inpatient admissions which would be more beneficial” |

Motivation Reflective |

Education Persuasion Enablement |

Provide resources/guideline easily accessible for reference (P1) Improvise present systems and process based on staff opinion and less time consumption to complete (P4) Utilise Community health providers for referrals (P2) |

| Domain. 12 (Intention) Motivation and initiative to change and better care |

2 | P8. Doctor.2: - “As part of their discharge letter, there is an opportunity provide guidance to the Primary Care Physician about what should be done next” P6. Doctor.1: - “Communicating with the ward and saying “look we’re admitting this person or they need admission, but during this admission perhaps, we could focus on why they keep coming back frequently or what we can do that’s extra to what we’re doing?” |

Motivation Reflective |

Environmental restructuring Education |

COPD discharge templates (P8) Direct referrals to ward or outpatient allied health for pulmonary rehabilitation (P1) |

| Domain. 13 (Social influences) Communication and suggestion of care might help |

2 | P3. Nurse.1:”Respiratory CNC won’t always come through Emergency and if it’s someone who’s going home, they’re probably seen as not that critical and I’m not sure how often they would be able to come or be willing to come down to Emergency” P6. Doctor.1:-“On our system we can flag frequent presenters so if it was used to streamline or communicate to the Respiratory Team then perhaps that could bring in some kind of intervention” P8. Doctor.2:- “Almost invariably, the last sentence to the GP is “can you please re-refer this patient to the Respiratory Outpatients for follow up”. This may or may not be done for the patient as it is not often followed up (p8) |

Opportunity Social |

Restriction Environmental restructuring Persuasion |

Improve interdisciplinary communication using digital technology (P6) Reassuring staff with less time consuming referrals may lead to improve adherence (P7, P3, P8) |

Abbreviations: COM-B, capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour model; TDF, theoretical domains framework; ED, emergency department; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCW, behaviour change wheel; GP, general practitioner; CNC, clinical nurse consultant.

Discussion

This research study is the first of its kind exploring modifiable factors to improve uptake of COPD guidelines from an interdisciplinary ED staff perspective. Knowledge, skills, behaviour and environmental context and resources have impacted the implementation and uptake of guidelines in clinical practice.1 Utilising the theoretical domains framework and behaviour change techniques provides a novel, contemporary approach that is adopted here to share the experience of the interdisciplinary teams and explore views on future implementation strategies that could be adopted within emergency departments. Emerging themes from the interviews consolidate that improving adherence to clinical guidelines was highly dependent on knowledge; skills; beliefs about capabilities; memory attention, decision process; behavioural regulation; environmental context and resources; social/professional role identity; reinforcement; beliefs about consequences and emotions. These domains applied into the COM-B, behaviour change wheel enlightened the research team with selection and recommendation of intervention strategies suggested by participants, validated through substantiated implementation frameworks and clinical practice behaviour change science. Adoption and implementation of improved strategies will have the potential to improve guideline adherence, patient outcomes and reduce COPD remissions and ED readmissions.17,26,31

Relevant key impediments to guideline adherence remain with a lack of knowledge of the existence of guidelines and the significance of timely or existing referrals (for example, referrals to a pulmonary rehabilitation program) services from the ED. Significance of time-efficient referral processes and identification of education and ongoing assistance with referral processes is vital in the ED to assist staff, patients and to meet the national targets of creating bed space for new patients within 4 hours of admission. Literature reviews and other adherence papers support this research interpretation as education initiatives and ongoing training is essential to influence staff to comply with COPD guidelines.1,16,19,20,26 Environmental hindrances such as patient acuity, resources and staffing during peak hours and in the winter timeframe in the department were identified as sources of concern. Strategies were identified to assist with the prioritisation of implementation of strategies that specifically focused on improving the uptake of COPD guidelines in practice. Interventions to be considered to augment this uptake of COPD guidelines include educational training (self-directed or department focussed), clinical reminders with easier access to concise guidelines, change champions in the departments, direct referrals to the community with the inclusion of pharmacist home medicine reviews, COPD discharge templates, time-efficient digital referrals from the ED and digital enablement of interdisciplinary communication pathways. Digital reminder or systems access for information of COPD guidelines would assist with easier utilisation of referrals and guidelines in practice in an unprecedented and challenging ED environment.3,16,18,32–34

The strategies likely to improve the implementation of COPD guideline adherence identified after mapping to the evidence-based framework to design behaviour change techniques according to the COM-B model are educational in-services, ED change champions steering the knowledge dissemination, digital referral and access to COPD resources for staff and patients. Interdisciplinary staff clinical behaviour change is integral to increase and sustain guideline adherence. Digitalizing and delegation with appropriate referrals will also provide time-efficient care in the Emergency departments (See Tables 4, 6, 7, 9 and 10). Preliminary findings of a systematic literature review and scoping review protocols (should you reference yourself up) exploring modifiable barriers to enhance COPD guideline adherence and referrals in the hospitals support the findings of the recommendations arising from this current study to promote uptake of COPD guidelines35,36 Targeted behaviours and recommended selection of 93 behaviour change techniques (BCT) recommended by the taxonomy and deducted from data analysis are categorised into capabilities, opportunities and motivation strategies.29 Capability components are demonstrated by specific skills and knowledge of guidelines and management of COPD patients, whereas opportunity components evaluate and instil social and environmental factors external to interdisciplinary clinicians to assist facilitation of change. Motivation components involve reflective or emotional processes that encourage uptake and clinical practice of guidelines.

The capability component in this model is explained as the physical and psychological ability to engage, comprehend and reason with the barriers. Problem behaviours acting as a barrier in this category are recommended to be approached with modelling and enablement. Identified interventions such as in-services training, provision of resources including self-directed study, time efficient and readily access, ED champions to lead new implementation, COPD ED discharge templates, and direct referrals by admin staff would assist to enhance uptake of guidelines (see Tables 2, 3, 5 and 6). Opportunity components in this model construe physical and social opportunities affordable by the staff in their clinical environment. Recommended approaches by the framework are restriction, environmental restructuring and enablement. Recommendations were made for more funding, increased staffing, dedicated administration staff to do referrals, digital platforms to promote quicker and clearer interdisciplinary communication and restructuring clinical processes to a time-efficient clinician-friendly manner to adapt to the bustling nature of the emergency departments (see Tables 4, 9 and 10). Motivation components comprise reflective and automatic motivation to address staff clinical behaviour, emotional responses, beliefs and intention towards utilising COPD clinical guidelines. Reflective motivation focuses on education, persuasion, incentivisation and coercion, whereas automatic motivation includes all mentioned strategies in addition to environmental restructuring, modelling and enablement. Recommendations from this study include time-efficient electronic referrals, automated electronic staff/patient information resources and discharge templates with respiratory department consultation and consensus to complement COPD guidelines adherence and management (see Tables 7, 8 and 10).

COPD is a multimodal disease that requires a multidisciplinary involvement of a comprehensive health care team that is skilled, knowledgeable and has the capacity to implement best practice strategies in line with national COPD guidelines. To enable clinicians, it is recommended that the roles within multidisciplinary teams are clear within and across disciplines and through implementation strategies. The contribution of all clinicians towards the preferential implementation of COPD guidelines in practice is indispensable to prevent readmission of patients within the ED. Future interventions and implementation strategies should adopt educational training, assistance and resource provision appealable to multidisciplinary teams and in an environment where online resources are readily available and accessible.

Conclusion

Barriers and potential solutions to improve COPD-X plan guideline adherence in the emergency department were explored through this study. Utilisation of a framework (TDF) and associated behaviour change technique application in conjunction with participants' recommendations suggest multiple intervention strategies to acquire guideline uptake in the emergency department. Education, training and provision of resources notably in easily accessible electronic formats and time-efficient software platforms are prominent and preferred implementation strategy to improve guideline adherence.

Strengths and Limitations

The multidisciplinary approach to this study assisted with capturing the experiences of clinicians from a range of health-related disciplines. However, this study was conducted in one acute care ED setting and hence generalizability will be limited. This facility did not employ a psychologist in the ED setting thus no inclusion of this area of allied health engagement could be captured. The inclusion of a psychological team member may have further assisted in providing emotional and anxiety-related strategies to patients in the ED. A limitation of the study was that the department did not employ respiratory physiotherapists or respiratory clinical nurses in the ED and a study that was inclusive of these clinicians may have contributed to different perspectives and findings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge input from Professor Ian Yang, Thoracic Physician at The Prince Charles Hospital and The University of Queensland, who provided comment on this study from a respiratory medicine point of view. We acknowledge all efforts, support and facilitation provided in the emergency department by Dr. Frances Kinnear, Dr. Alastair Newton and Dr. Polash Adhikari. We express deep gratitude to all research participants for providing us with their valuable time for the prospects of improving patient care.

Abbreviations

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BCT, Behaviour Change Taxonomy; BCW, Behaviour Change Wheel; HREC, Human Research Ethics Committee; ED, Emergency department; TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework.

Data Sharing Statement

To protect the rights and confidentiality of participant details raw data will only be available to members of the research team. No data will be shared externally or in any public forum. Only de-identified data summaries will be shared publicly.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

Ethics approval was obtained prior to commencement from the Metro North Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC EC00168/55098). A site-specific ethics/administrative approval including a research agreement between Metro North hospital (The Prince Charles hospital) and the University of Southern Queensland was acquired. Ethics approval was also gained from the University of Southern Queensland, Human Research Ethics Committee (H19REA308). The ethics was categorised as low risk. Signed participant consent was obtained and a participation information sheet was provided to each participant prior to interviews. Research collaboration agreement for publication was obtained between southern Queensland and Metro north hospital. Participants' information sheet included the publication of anonymised responses and this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Data management adhered to the Metro North hospital and University of Southern Queensland research data management policy. De-identified hard copy data will be stored by the Principal investigator in a locked filing cabinet with digital transcribed copies of the interviews stored in password-protected University research cloud drive.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Lodewijckx C, Sermeus W, Vanhaecht K, et al. Inhospital management of COPD exacerbations: a systematic review of the literature with regard to adherence to international guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(6):1101–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seys D, Bruyneel L, Decramer M, et al. An international study of adherence to guidelines for patients hospitalised with a COPD exacerbation. COPD: J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2017;14(2):156–163. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2016.1257599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly A-MA-M, Van Meer O, Keijzers G, et al. Get with the guidelines: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in emergency departments in Europe and Australasia is sub-optimal. Intern Med J. 2020;50(2):200–208. doi: 10.1111/imj.14323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis A, Axson EL, Potts J, et al. Protocol for a systematic literature review and network meta-analysis of the clinical benefit of inhaled maintenance therapies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e025048. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang IA, George J, Jenkins S, et al. The COPD-X plan: Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2018. 2018.

- 6.Gold PM. The 2007 GOLD Guidelines: a comprehensive care framework. Respir Care. 2009;54(8):1040–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford G, Brooksbank MA, Brown M, et al. Unmet needs of people with end‐stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: recommendations for change in Australia. Intern Med J. 2013;43(2):183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.welfare, A.I.o.h.a. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). H.a. welfare, Editor. web report; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Institute of health and Welfare. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. H.a. welfare, Editor. 2017.

- 10.Kelly AM, Holdgate A, Keijzers G, et al. Epidemiology, treatment, disposition and outcome of patients with acute exacerbation of COPD presenting to emergency departments in Australia and South East Asia: an AANZDEM study. Respirology. 2018;23(7):681–686. doi: 10.1111/resp.13259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moloney C. Reducing avoidable COPD emergency room presentations: an integrated cross-health service utilisation scoping initiative in South Queensland. Respirology. 2020;25(S1):143. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rana R, Gow J, Moloney C, et al. Does distance to hospital affect emergency department presentations and hospital length of stay among COPD patients? Intern Med J. 2020. doi: 10.1111/imj.15014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australasian College For Emergency Medicine. Triage. 2020. [cited 2021]; Available from: https://acem.org.au/Content-Sources/Advancing-Emergency-Medicine/Better-Outcomes-for-Patients/Triage. Accessed February27, 2021.

- 14.Harrison SL, Goldstein R, Desveaux L, et al. Optimizing nonpharmacological management following an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1197. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S41938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrado A, Rossi A. How far is real life from COPD therapy guidelines? An Italian observational study. Respir Med. 2012;106(7):989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overington JD, Huang YC, Abramson MJ, et al. Implementing clinical guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: barriers and solutions. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(11):1586–1596. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.11.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Considine J, Botti M, Thomas S. Emergency department management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Audit of compliance with evidence based guideline. Intern Med J.2011;41(1a):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.14455994.2009.02065.x.PMID:19811556 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Sha J, Worsnop CJ, Leaver BA, et al. Hospitalised exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: adherence to guideline recommendations in an Australian teaching hospital. Intern Med J. 2020;50(4):453–459. doi: 10.1111/imj.14378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartels W, Adamson S, Leung L, Sin DD, Van Eeden SF. Emergency department management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: factors predicting readmission. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;Volume 13:1647–1654. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S163250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kruis AL, Smidt N, Assendelft WJ, et al. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel. A Guide to Designing Interventions. 1st ed. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 2014:1003–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alsubaiei M, Frith PA, Cafarella PA, et al. COPD care in Saudi Arabia: physicians’ awareness and knowledge of guidelines and barriers to implementation. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(5):592–595. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pothirat C, Liwsrisakun C, Bumroongkit C, et al. Comparative study on health care utilization and hospital outcomes of severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease managed by pulmonologists vs internists. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:759. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S81267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitchlu A, Abdelshaheed T, Tullis E, et al. Gaps in the inpatient management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation and impact of an evidence-based order set. Can Respir J. 2015;22(3):157–162. doi: 10.1155/2015/587026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly AM, Van Meer O, Keijzers G, et al. Get with the guidelines – management of COPD in emergency departments in Europe and Australasia is sub-optimal. Intern Med J. 2020;50:200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig LE, McInnes E, Taylor N, et al. Identifying the barriers and enablers for a triage, treatment, and transfer clinical intervention to manage acute stroke patients in the emergency department: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework (TDF). Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0524-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munday J, Delaforce A, Forbes G, et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of perioperative hypothermia prevention practices from the perspectives of the multidisciplinary team: a qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:395. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S209687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, et al. Anesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: application of the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians’ decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):52. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerber A, Moynihan C, Klim S, et al. Compliance with a COPD bundle of care in an Australian emergency department: a cohort study. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(2):706–711. doi: 10.1111/crj.12583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cousins JL, Wark PA, McDonald VM. Acute oxygen therapy: a review of prescribing and delivery practices. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]