Abstract

Purpose

Interleukin (IL)-1α/IL-1β and transforming growth factor (TGF)β1/TGFβ2 have both been promoted as “master regulators” of the corneal wound healing response due to the large number of processes each regulates after injury or infection. The purpose of this review is to highlight the interactions between these systems in regulating corneal wound healing.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the literature.

Results

Both regulator pairs bind to receptors expressed on keratocytes, corneal fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts, as well as bone marrow-derived cells that include fibrocytes. IL-1α and IL-1β modulate healing functions, such as keratocyte apoptosis, chemokine production by corneal fibroblasts, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) production by keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts, expression of metalloproteinases and collagenases by corneal fibroblasts, and myofibroblast apoptosis. TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 stimulate the development of myofibroblasts from keratocyte and fibrocyte progenitor cells, and adequate stromal levels are requisite for the persistence of myofibroblasts. Conversely, TGFβ3, although it functions via the same TGF beta I and II receptors, may, at least in some circumstances, play a more antifibrotic role—although it also upregulates the expression of many profibrotic genes.

Conclusions

The overall effects of these two growth factor-cytokine-receptor systems in controlling the corneal wound healing response must be coordinated during the wound healing response to injury or infection. The activities of both systems must be downregulated in coordinated fashion to terminate the response to injury and eliminate fibrosis.

Translational Relevance

A better standing of the IL-1 and TGFβ systems will likely lead to better approaches to control the excessive healing response to infections and injuries leading to scarring corneal fibrosis.

Keywords: cornea, growth factors, growth factor receptors, transforming growth factor (TGF) beta-1, TGF beta-2, interleukin-1 (IL) alpha, interleukin-1 beta, stromal-epithelial interactions, fibrosis, corneal scar

The Corneal Wound Healing Response to Injury

Injuries to the cornea most commonly occur via the corneal epithelium in the form of traumatic, infectious, toxic, or surgical injuries to the epithelium alone or to the epithelium and underlying stroma.1 Another route of injury, however, typically mediated by some type of immune response, can enter the peripheral stroma directly via the limbal blood vessels.2 Finally, the corneal endothelium can be injured either via a perforating injury through the epithelium and deep stroma, or directly through processes such as herpes simplex endotheliitis.3 This paper, for the most part, will focus on anterior injury models, with reference to the other modes of injury when applicable. This topic has recently been reviewed,4 but a brief overview will be helpful.

The first notable change in the stroma after epithelial or epithelial-stromal injury is apoptosis of the underlying keratocytes (Figs. 1A, 1B).5 The site and extent of this apoptosis, and whether there is also or in some cases exclusively necrosis (for example in severe alkali burns6) of keratocytes, is dependent primarily on the type and extent of the injury.4 This stromal apoptosis response occurs, at least to a limited extent, even if the injury is confined to the epithelium, for example, in a simple corneal abrasion or herpes simplex epithelial keratitis. Importantly, a posterior corneal keratocyte apoptosis response and similar ensuing posterior corneal wound response can occur with injuries to the corneal endothelium.7,8

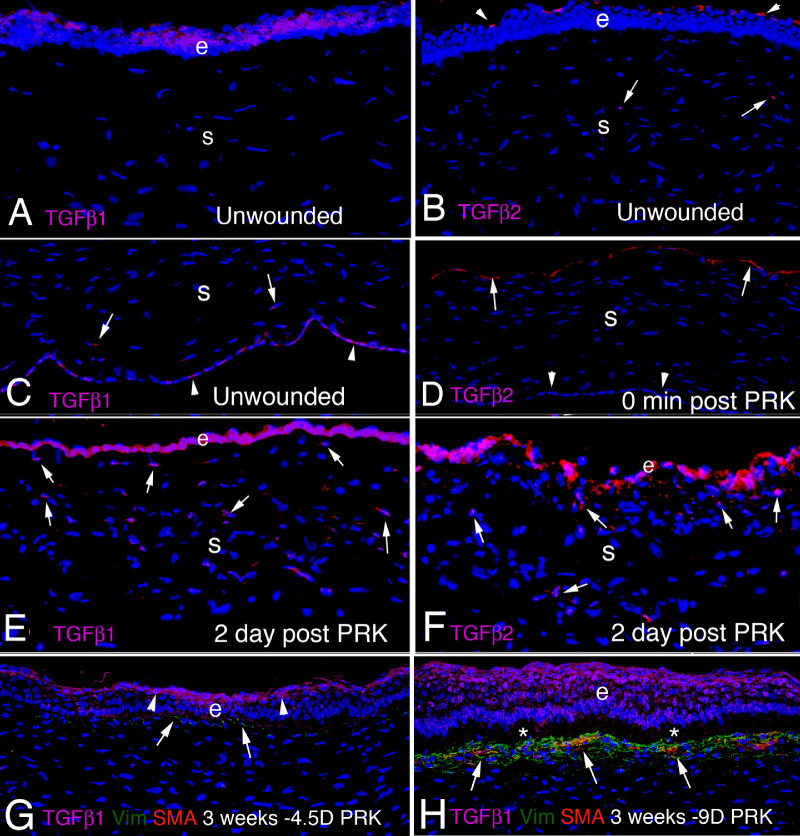

Figure 1.

Non fibrotic and fibrotic healing responses to injury in the cornea . (A) In the uninjured cornea the stroma is populated with quiescent keratocytes. Inactive TGFβ1 is produced in small amounts by corneal epithelial and endothelial cells, while small amounts of inactive TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 are also present in the tears—restricted from passage through the epithelium by an epithelial barrier function.9 The EBM and Descemet's membrane prevent passage of TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 into the stroma, although small amounts of TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 below the level of IHC detection may be sequestered in the stromal matrix (not shown). IL-1α76–78 (and also inactive IL-1β81) are within corneal epithelial cells. (B) Within minutes to hours of epithelial-stromal injury, including the EBM, inactive TGFβ1 production is upregulated in the epithelium, and TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 are present at increased levels in the tears (from the lacrimal gland and possibly conjunctiva, goblets cells and other cells), and enter the stroma in high levels in the absence of EBM.9 TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 are activated by collagenases and metalloproteinases (and thrombospondin-1) in the stroma, and integrins in the epithelium (as well as possibly other activators).58–60 IL-1α (and pro-IL-1β) are released from injured corneal epithelial cells (IL-1β is activated by neutrophil serine proteases and other enzymes34,35) and high concentrations of IL-1α and IL-1β trigger apoptosis of subepithelial keratocytes1,5 via upregulation of Fas ligand by keratocytes (that constitutively express Fas).55,171 Surrounding keratocytes that escape the wave of apoptosis transition to corneal fibroblasts and, driven by TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, begin development into myofibroblasts.9 IL-1α and IL-1β also upregulate surviving corneal fibroblast production of HGF and KGF that modulate corneal epithelial cell migration, proliferation and differentiation to heal the epithelial defect.81 Fibrocytes (not shown) attracted from limbal blood vessels by chemokines produced by corneal fibroblasts also begin TGFβ1- and TGFβ2-driven development into myofibroblasts.12,116 Limited amounts of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 are also produced by both vimentin-positive and vimentin-negative stromal cells9 (not shown). (C) In corneas that heal without scarring fibrosis, the EBM is regenerated by the coordinated action of the healed epithelium and cooperating keratocytes/corneal fibroblasts (that produce EBM components such as perlecan and nidogens), and epithelial barrier function is re-established.9 Deprived of sufficient epithelial and tear TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 by the regenerated EBM, myofibroblast precursors and corneal fibroblasts either undergo apoptosis or revert to keratocytes.9 Little disordered extracellular matrix is produced and stromal opacity is limited.1 (D) If the EBM is not regenerated in a timely manner (typically a few weeks), then myofibroblast precursors, driven by epithelial, tear, and, possibly, stromal cell-derived TGFβ1 and TGFβ2,9 complete development into mature myofibroblasts, that are themselves opaque due to decreased production of corneal crystallins,23 and produce large amounts of stromal disordered extracellular matrix associated with scarring fibrosis.1,9,17,129 This scarring fibrosis persists for months or years, or even indefinitely, until such time as the EBM is once again regenerated through the coordinated action of corneal fibroblasts/keratocytes and corneal epithelial cells (not shown).9,129 Thereby deprived of requisite TGFβ1 and/or TGFβ2, the myofibroblasts undergo late apoptosis9,27,129 or revert to precursor cells. Keratocytes repopulate the subepithelial stroma, and reorganize the disordered extracellular matrix and re-establish transparency (not shown). A similar posterior stromal keratocyte apoptosis7 and scarring fibrosis8 response can occur after injury to the endothelium and Descemet's membrane (not shown). Severe corneal injuries involving both the EBM and Descemet's membrane can produce fibrosis of the full-thickness stroma (not shown).14 Illustration by David Schumick, BS, CMI. Reprinted with the permission of the Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2021. All Rights Reserved.

Depending on the extent of injury, and likely genetic influences and possibly other unknown factors, the ensuing wound healing response typically goes one of two directions—nonfibrotic (Fig. 1C) or fibrotic corneal wound healing (Fig. 1D).4,9, Other authors have referred to this bifurcation as regenerative versus fibrotic healing.10,11 Initially, the two pathways take the same route, with the generation of a population of keratocan-negative, vimentin-positive corneal fibroblasts from keratocytes that escape the initial wave of apoptosis and necrosis.9 At this point, there is also entry of bone marrow-derived cells, including CD34, CD45, and collagen type 1-positive fibrocytes, from the limbal blood vessels.12 In addition, there is healing and, hopefully, closure of the corneal epithelium.13 The corneal fibroblasts and fibrocytes are detected primarily in the subepithelial stroma after anterior corneal injuries,9 but can be generated throughout the entire stroma with severe injuries, toxic exposures, or infections.14

Some of these corneal fibroblasts and fibrocytes begin a developmental pathway, regardless of how mild or severe the epithelial, epithelial-stromal, endothelial, or endothelial-stromal injury happened to be. This is driven primarily by transforming growth factor (TGF)β1, TGFβ2, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) from tears and epithelial cells.9 In addition, but to a lesser extent, resident and invading bone marrow-derived cells may produce these growth factors.9 Ongoing stimulation of the precursor cells by TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and PDGF causes them to eventually develop into mature vimentin-positive, alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive myofibroblasts,9,15 the cells in large part responsible for the development of scarring fibrosis in the corneal stroma.4,16

Whether or not mature SMA-positive myofibroblast fully develop in the corneal stroma—a process typically taking a minimum of 1 week and in humans often a few months—determines whether the cornea heals with or without scarring fibrosis.4,10,11 Thus, the progeny of the myofibroblast precursor corneal fibroblasts and fibrocytes, driven by TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and PDGF, and absolutely dependent on an ongoing adequate source of TGFβ1 and/or TGFβ2, develop into a poorly characterized intermediate pre-myofibroblast cell type that is vimentin-positive, but not yet SMA-positive.16

Regeneration of the epithelial basement membrane (EBM) determines whether these myofibroblast precursors complete their development and secrete large quantities of disordered collagen type 1, collagen type 2, and other disordered extracellular matrix materials that are found in fibrosis.17,18 The EBM normally regenerates within 1 to 2 weeks via the cooperative interactions of the corneal epithelial cells and corneal fibroblasts and/or keratocytes (see Fig. 1C).9,19

The first step in regeneration of the EBM is closure of the epithelium because if an epithelial defect develops and persists for more than 1 to 2 weeks, myofibroblasts and scarring fibrosis invariably develop.20 Even if the epithelial defect does close, the EBM may not be regenerated by the coordinated production and localization of EBM components by epithelial cells, subepithelial corneal fibroblasts, and/or keratocytes, depending on the extent of injury (and the level of initial keratocyte loss via apoptosis/necrosis), stromal surface irregularity, and likely other factors (see Fig. 1D).18,19,21 Two recent studies have pointed to perlecan production and incorporation by corneal fibroblasts and/or keratocytes into the nascent EBM as a major factor in normal versus defective regeneration of the mature, fully functional EBM.9,22

The reason that mature EBM regeneration is the key to nonfibrotic versus fibrotic corneal stromal healing is because the fully regenerated EBM is the paramount regulator of ongoing entry of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, as well as PDGF, from the overlying epithelium and tears.9,18–21 When the EBM normally regenerates, TGF beta-1 and TGF beta-2 from the tears and epithelium are prevented from entering the underlying stroma. However, in the absence of fully mature EBM with normal perlecan, and possibly other EBM components derived from corneal fibroblasts and keratocytes, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 gain ongoing entry into the corneal stroma in sufficient amounts to drive the development of mature myofibroblasts, and maintain their viability (see Fig. 1D). If at any time point mature EBM is regenerated, then myofibroblast precursors and any mature myofibroblasts that have developed undergo apoptosis. Corneal fibroblasts and keratocytes then repopulate that area of stroma and restore the normal collagen and extracellular matrix (ECM) structure of the stroma associated with transparency. If mature EBM is not fully regenerated, then myofibroblast precursors and myofibroblasts receive ongoing TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 from the epithelium and tears, and to a lesser extent corneal stromal cells, and persistent scarring fibrosis is established in the stroma.9 Importantly, a lower level of stromal opacity, that is clinically referred to as “haze,” can be generated by corneal fibroblasts that do not develop into mature myofibroblasts.23

A similar fibrosis process can occur in the posterior cornea following injury to the corneal endothelial cells and associated Descemet's basement membrane.8,24,25 The source of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 after these posterior injuries are the aqueous humor and residual peripheral endothelial cells.8,24,25 In this case, however, there is much less tendency for Descemet's membrane to be regenerated by coordinated action of endothelial cells and overlying keratocytes or corneal fibroblasts, and the posterior corneal fibrosis tends to persist indefinitely.14,24,25 Full-thickness corneal fibrosis can occur after extensive injuries damaging both the EBM and Descemet's basement membrane, although there is more tendency for the EBM to eventually regenerate and the anterior stromal fibrosis to be resolved.14

Even in corneas that develop extensive myofibroblasts and fibrosis, the fibrosis can eventually decrease, or even resolve, if the EBM is repaired.18–21,24–26 This process likely occurs by eventual penetration of keratocytes and/or corneal fibroblasts through the fibrotic tissue to cooperate with the overlying basal epithelial cells in regeneration of the normal mature EBM, with the ultrastructural regeneration of lamina lucida and lamina densa signaling this process.18–21,24,25 When this occurs, persistent myofibroblasts, or even recently developed myofibroblasts, because myofibroblast and fibrosis turnover is dynamic over time,8 are deprived of mandatory supplies of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, and subsequently undergo apoptosis.4,27

Peripheral corneal wound healing and scarring that occurs with disorders, such as peripheral ulcerative keratitis and Mooren's ulcers,28,29 likely share some characteristics with anterior and posterior corneal injuries, but likely have more involvement of bone marrow-derived cells, such as monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes. The wound healing responses in these peripheral corneal disorders have not been well-characterized.

General Overview of the Interleukin-1 Cytokines, Antagonists, and Receptors

The interleukin (IL)-1 family of cytokines comprises 11 members that includes 7 pro-inflammatory agonists (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-33, IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ) and 4 antagonists (IL-1 receptor antagonist [IL-1Ra], IL-36 receptor antagonist, IL-37, and IL-38).30,31 The IL-1 receptor family includes 10 members that includes cytokine-specific receptors, coreceptors, and inhibitory recptors.30,31

IL-1 cytokines do not possess a secretory sequence, with the exception of IL-1Ra, and are secreted via injury or death of a cell.30,31 Pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 are produced as biologically inert pro-peptides that require cleavage by caspase-1 upon inflammasome activation to generate the active cytokines. The inflammasome is a cytosolic multiprotein signaling complex that is part of the innate immune system and has a critical role in activating inflammatory responses in the cornea and other organs.32,33 In addition, IL-36 also requires N-terminal processing for activation.30,31 However, pro-IL-1β can be cleaved and activated by neutrophil serine proteases, such as proteinase 3, also known as PRTN3, and elastase, as well as by mast cell-derived serine proteases, including chymase.34,35

IL-1α and IL-33 are typically released by cell damage or cell death, and, therefore, have been classified as “alarmins.” Even though the full-length pro-IL-1α and pro-IL-33 can bind their receptors and trigger intracellular signaling, the activities of both of these cytokines are markedly enhanced by protease cleavage.36,37

Previously published work has revealed important insights into the functions of IL-18, IL-33, IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ and their antagonists and receptors in the cornea,38–45 and have been shown to have roles in microbial keratitis40,44 and atopic keratoconjunctivitis45 but nothing about a possible role in cooperation with TGF beta isoforms. The present review will focus on IL-1α and IL-1β because of their better characterized interactions with the TGFβ growth factor receptor system in the cornea.

Endogenous inhibitors of IL-1α and IL-1β modulate receptor binding and activation, and include IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) and IL-1 decoy receptor.30,31 IL-1Ra is usually produced by the same cells that also express IL-1α or IL-1β—including epithelial cells, monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells.30,31 IL-1Ra, like IL-1α and IL-1β, binds with high affinity to IL-1 receptor, type 1 (IL-1R1), but the needed conformational change in the receptor is not produced and, therefore, the coreceptor IL-1RAcP is not recruited, so there is no activated receptor-mediated intracellular signal transduction.46 Therefore, IL-1Ra competes with IL-1α and IL-1β for the binding to IL-1R1 and, thus, competitively inhibits IL-1 activity and regulates IL-1-mediated cellular function. One study showed IL-1Ra must be present at over 100-fold excess over IL-1α and IL-1β to effectively block IL-1-mediated responses in cells that express IL-1R1.47

There are four isoforms of IL-1Ra— a secreted isoform (sIL-1Ra) and three cell-associated isoforms (icIL-1Ra1, icIL-1Ra2, and icIL-1Ra3), which are all capable of antagonizing IL-1 activity. The cell associated IL-1Ra isoforms can also be released into the circulation by dying cells or actively secreted by a presently unknown mechanism. All four isoforms can, therefore, bind with high affinity to IL-1R1 to antagonize the effects of IL-1α and/or IL-1β.30,31 The expression, release, and coordinated function of these IL-1 receptor antagonists is complex, but undoubtedly important, in controlling the powerful effects of IL-1α and/or IL-1β.

Anakinra (product name Kineret; Amgen, Seattle, WA, USA) is a recombinant, nonglycosylated form of the human IL-1Ra. It differs from native human IL-1Ra with the addition of a single methionine residue at its amino terminus and is produced using an Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacterial expression system. Although typically used for severe auto-immune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, it has been used in clinical trials in the treatment of severe ocular conditions poorly responsive to other treatments, such as dry eye48 and scleritis.49 It has also been used successfully in animal studies for the treatment of alkali burns in rats50 and to increase corneal transplant survival in mice.51 Although it reportedly is well-tolerated in humans and animals, it has not been used widely, in part possibly to the expense of treatment and clinical trials to expand its use.

IL-1 receptor, type 2 (IL-1R2) is a decoy receptor expressed by many cells, including keratinocytes, endometrial epithelial cells, T and B cells, monocytes, and polymorphonuclear cells.30 IL-1R2 binds IL-1α and IL-1β with high affinity, but this small protein has a short cytoplasmic terminus that is incapable of signal transduction.30,52 As a decoy, IL-1R2 also modulates the effects of IL-1α and IL-1β on cells that express it.

Both IL-1α and IL-1β bind to and produce their effects via IL1R1.30,31,53 Binding of IL-1α or IL-1β to IL1R1 leads to the activation of a series of protein kinases that subsequently trigger an increase in the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory genes,30,53 and in some cells triggers apoptosis,54,55 likely depending on the local concentration of IL-1α and IL-1β.

General Overview of the TGFβ Family of Growth Factors and Receptors

TGFβ1 was the first member identified in the TGF family.56 However, this large family of modulators now includes 33 related proteins, including the TGF betas, bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), activans, growth and differentiation factors (GDFs), nodal, Mullerian inhibiting substance, and a large number of related receptors. This review focuses on the family members TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3, and their receptors.

TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3 are produced as a homo-dimeric pro-proteins that undergo proteolytic cleavage in the trans-golgi network by furin-like enzymes. This gives rise to a C-terminal mature TGFβ dimer and N-terminal pro-peptide known as latency-associated peptide (LAP).57 LAP remains noncovalently associated with mature TGFβ, which keeps the TGFβ inactive in a “small latent complex” (SLC). This SLC forms a complex with another protein called latent TGFβ binding protein (LTBP) through intermolecular disulfide bonds, and constitutes the “large latent complex” (LLC).57 This is the most abundant secreted form of each TGFβ isoform in most tissues.51 Each latent TGFβ isoform is activated in vivo by several molecules in the tissues where they function—such as thrombospondin 1 (TSP-1), integrins, including integrin αVβ6, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2, and MMP9.58–60

All three isoforms of TGF-beta signal via three TGFβ receptors—TGFBR1, TGFBR2, and TGFBR3.56,57 “Canonical” TGF-beta signaling occurs after one of the TGFβ growth factor dimers bind to TGFBR2, and the TGFβ-TGFBR2 complex subsequently recruits and phosphorylates TGFBR1. This combined TGFBR2-TGFBR1 complex subsequently phosphorylates the downstream modulators SMAD2 and SMAD3. This SMAD2-SMAD3 complex associates with SMAD4, and the SMAD2-SMAD3-SMAD4 complex translocates to the cell nucleus to control transcription of TGFβ modulated genes.61–64

On the other hand, if SMAD7 is recruited to the complex of activated TGFBRs and/or phosphorylated SMAD2/3, it triggers their degradation by SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase within proteasomes.65,66 Thus, SMAD7 downregulates the TGFβ response, and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway modulates signaling by TGFβ1, TGFβ2, or TGFβ3. homologous to the E6-accessory protein C-terminus (HECT)-type E3 ubiquitin ligases, SMAD ubiquitin regulatory factor 1 (Smurf1), SMAD ubiquitin regulatory factor 1 (Smurf2), and RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase (ROC1-SCF[Fbw1a]), have been identified as key participants in SMAD degradation.67

However, TGFβ1, TGFβ2, or TGFβ3 binding to TGFβRs can also activate “noncanonical” TGF-beta signaling when other cytoplasmic proteins are recruited to the activated TGF-beta-receptor complex and activate intracytoplasmic kinases—including MAPKs, JNK, ERK, P38, phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/PKB, and ROCK.68–70 These kinases are able to phosphorylate the linker regions of the SMAD2/3 complex, and signaling associated with such linker region phosphorylation has been defined as non-SMAD (or SMAD-independent) signaling.70

The proteoglycan TGFBR3 (also named betaglycan) can bind all three TGFβ isoforms with high affinity, but does not have kinase activity. It facilitates binding of TGFβ2 to TGFBR2,71 and, therefore, could be an important regulator of TGFβ2 responses over TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 effects in some cells. TGFBR3 has also been shown to trigger noncanonical pathways, suggesting it is not merely a coreceptor.72

Thus, TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3 compete for the same receptors and the stoichiometry of the available, activated isoforms is likely very important in the TGFβ signaling effect on a particular cell,73,74 and the context of the surrounding cellular milieu, including other cytokines and growth factors that are binding and activating their receptors.

Several agonists or antagonists have been shown to facilitate or inhibit binding of activated TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3 to their receptor complexes.75 For example, KCP/CRIM2, CHRDL1, and BMPER/CV-2 act as both agonists and antagonists, depending on the particular growth factor and whether or not other factors are present in the environment.71 Other modulators, such as follistatin (FST), FSTL1, BMPER/CV-2, and Lefty, can bind to TGFBR1 or TGFBR2 to form an inactive, nonsignaling complex, and thereby downregulate the cells’ response to TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3.75

Expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1Ra, and IL-1 Receptor in the Cornea

IL-1α is constitutively produced by the corneal epithelial (Fig. 2) and corneal endothelial cells,76–78 as it is in most epithelial, endothelial, and stromal cells studied to date,31,79 although IL-1α protein expression is typically minimal in the stroma of unwounded corneas (see Fig. 2).76–78 IL-1α protein, however, has been detected in stromal cells in wounded corneas and it has been shown to be active in an autocrine loop in corneal fibroblasts in culture.80 IL-1β expression has been reported to be restricted primarily to immune cells,31,79 although IL-1β has been detected in epithelium and endothelium in unwounded human corneas in one study.81 In another study,82 IL-1α and IL-1β proteins were found in both SMA-positive cells (myofibroblasts) and SMA-negative cells (keratocytes, corneal fibroblasts, and/or immune cells) after photorefractive keratectomy injury in rabbits.

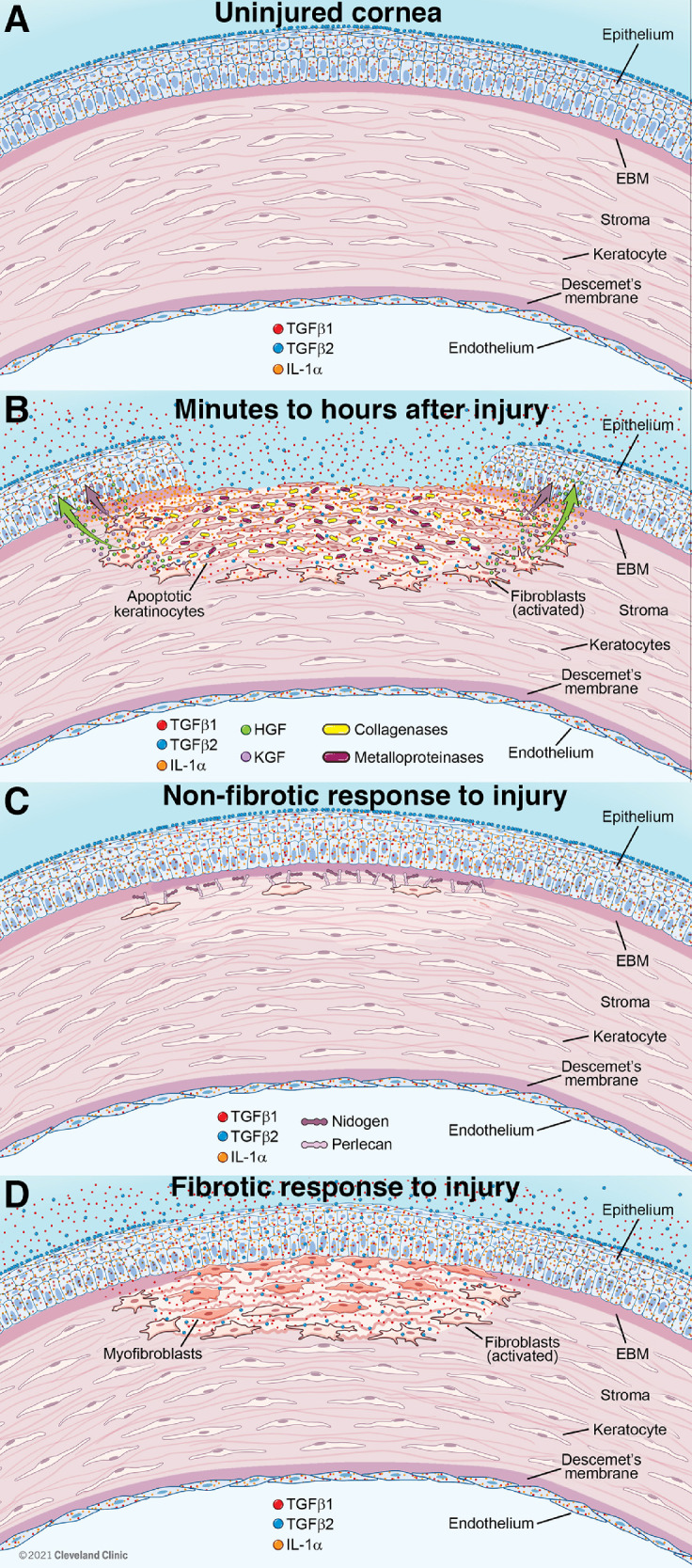

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry for IL-1α in the unwounded human cornea. IL-1α is constitutively (continuously) produced in the corneal epithelium (E) and endothelium (not shown). Little IL-1α is detected in cells in the stroma (s) in the unwounded cornea. IL-1α is released when epithelial cells are injured or die, and passes into the tear film and anterior stroma (400 times magnification). Republished with permission from Wilson SE, et al., Exp. Eye Res. 1994;59:63-71.

Each of the forms of IL-1Ra is produced by corneal epithelial cells, including ex vivo human corneal epithelium, and stromal cells, but not by corneal endothelial cells.83–87 Corneal epithelium expresses high levels of IL-1Ra, as it does IL-1α, suggesting the IL-1Ra modulates IL-1 function when both are released by corneal epithelial injury. Expression of IL-1ra isoforms has apparently not been studied after corneal injury in situ.

IL-1 type I receptors are expressed by all corneal cells,88,89 including myofibroblasts,90 although the IL-1 receptor family has become more complex53 and the expression of many of the other IL-1 receptor family members has not been studied in corneal cells.

IL-1α and IL-1β are released and activated31,79 by injury or death of the corneal epithelial or endothelial cells after injury and modulate numerous functions of stromal cells during the wound healing process.91,92 The specific effect released IL-1α or IL-1β has on a particular stromal cell likely depends on factors, such as the specific stromal cell phenotype, the localized concentration of the cytokine, the context of other growth factors and cytokines simultaneously activating receptors on that cell, and other yet to be discovered dynamics.91,92

Expression of TGFβs and TGFβ Receptors in the Cornea

TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 are present in normal tears,93,94 and TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3 are present in the aqueous humor.95–98 One source of the TGFβ in tears is the corneal epithelium because normal ocular surface epithelium produces TGFβ1 (Fig. 3), and TGFβ3, and these growth factor isotypes are likely released with normal turnover of epithelial cells.9 TGFβ2 is not expressed in the unwounded rabbit corneal epithelium (see Fig. 3).9,77,78,99 Normal unwounded corneal endothelial cells also produce TGFβ1 (see Fig. 3C), but not TGFβ2 (see Fig. 3D).76,78 In unwounded rabbit corneas (Figs. 3A, 3B), stromal cell production of TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 protein is relatively low.9,78 TGFβ2 is not detectible in unwounded rabbit corneal epithelial cells, but is present on the epithelial surface of unwounded corneas (see Fig. 3B) and is detectible on the stromal surface immediately after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) in rabbits (see Fig. 3D)9—likely deposited there from the tears.91 However, after PRK injury to the cornea, TGFβ1 (see Fig. 3E) and TGFβ2 (see Fig. 3F) proteins are detectible in many stromal cells that include keratocytes, corneal fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and some bone marrow-derived cells.9,100–103 TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 mRNAs are also upregulated in corneal epithelial and endothelial cells proximate to the injury.104–106 TGF beta-2 LAP has also been detected in human corneal epithelium and stroma, and TGFβ3 LAP is present in the subepithelial stroma.107

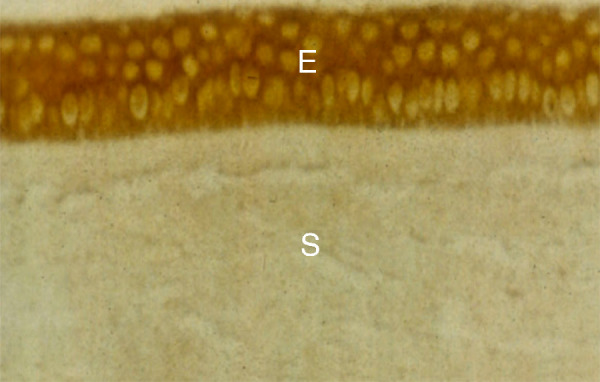

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry for TGF β 1 and TGF β 2 in rabbit corneas. (A) TGFβ1 is present in the unwounded corneal epithelium (e), but few cells in the stroma (s) express the growth factor. (B) In the unwounded cornea, TGFβ2 is not detected in epithelial cells, but there are deposits of TGFβ2 adherent to the epithelial surface (arrowheads). A rare cell in the stroma (s) expressed TGFβ2 (arrows). (C) The normal unwounded corneal endothelium (arrowheads) expresses TGFβ1, as do a few posterior stromal cells (arrows). (D) Immediately following -9 D PRK in rabbits, TGFβ2 is detected on the stromal surface (arrows), likely deposited from the tears. Note no TGFβ2 is detected in corneal endothelial cells (arrowheads). (E) At 2 days after -9 D PRK, TGFβ1 protein is detected in the healing epithelium (e) and in cells (arrows) in the stroma (s) that could include keratocytes, corneal fibroblasts, and bone marrow-derived immune cells. The TGFβ1 associated with the monolayer of healing corneal epithelial cells is likely derived from the epithelial cells themselves and the tears. (F) At 2 days after -9 D PRK, TGFβ2 is detected in the healing epithelium (e) and in cells (arrows) in the stroma (S) that could include keratocytes, corneal fibroblasts, and bone marrow-derived immune cells. (G) At 3 weeks after -4.5 D PRK in the rabbit cornea, epithelial TGFβ1 is present at higher levels than in the unwounded cornea, but is confined to the superficial epithelium (arrowheads). A line of vimentin+ cells (arrows) is present in the subepithelial stroma, but few of these cells have developed into SMA+ myofibroblasts. (H) Conversely, at 3 weeks after higher injury -9 D PRK in the rabbit cornea, epithelial TGFβ1 is present throughout the hyperplastic corneal epithelium, albeit at higher concentration in the superficial epithelium. A cluster of SMA+ vimentin+ myofibroblasts (arrows) is present in the subepithelial stroma. Some of these myofibroblasts or nearby cells are TGFβ1+. The asterisk (*) indicates artifactual separation of the epithelium from the stroma that occurs during tissue sectioning due to a defective EBM at this point after -9 D PRK.9 Magnification 200 times, except D is 100 times. Blue is DAPI in all panels. See reference #9 for other views and time points.

TGF beta receptors 1 and 2 have been detected by immunohistochemistry in the epithelium and stroma of unwounded and wounded rat corneas.102,108 TGF beta receptor 1, 2, and 3 are expressed by human corneal stromal fibroblasts in vitro.109

Corneal Cellular Functions With Known Interactive Regulation by IL-1 and TGFβ

IL-1-Mediated Myofibroblast Apoptosis Antagonistic to profibrotic TGFβ

IL-1α or IL-1β triggers myofibroblast apoptosis in vitro if the available concentration of apoptosis-suppressive TGFβ is low.100 Thus, after injury to the corneal epithelium or endothelium, that includes injury to the EBM or Descemet's basement membrane, respectively,8,17,18,24 TGFβ1 from tears and corneal epithelium (and TGFβ2 from tears) penetrates into the stroma and drives development of mature myofibroblasts from keratocyte and fibrocyte precursor cells.9 This process continues until such time that the damaged basement membranes are regenerated or replaced, which leads to a drop in stromal TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 coming from the epithelium, tear film, and/or aqueous humor.8,17,18,24 SMA-negative cells, such as corneal fibroblasts, keratocytes, and/or inflammatory cells that enter the stroma, produce IL-1α and/or IL-1β that act in paracrine fashion to trigger myofibroblast apoptosis.82,100 This occurs especially in the region where there is fibrosis in the cornea after injury and SMA-positive myofibroblasts are present at high density.82 That study also showed that a small percentage of SMA-positive myofibroblasts present in an area of fibrosis in the stroma after injury produce IL-1α and/or IL-1β, suggesting that myofibroblast apoptosis is also regulated via autocrine mechanisms in corneas with fibrosis.

These in vitro interactions were confirmed in a subsequent study using B6; 129S1-Il1r1tm1Roml/J homozygous IL-1RI knockout mice compared to control B6129SF2/J mice that had myofibroblast-generating irregular phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) performed with an excimer laser in one eye.90 SMA-positive myofibroblast density was significantly higher in the IL-1RI knockout group than in the control group at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months after the irregular PTK. In addition, at 6 months after the irregular PTK, the mean TUNEL+ stromal cells in the subepithelial 50 µm of stroma was significantly lower in the IL-1RI knockout group compared to the control group.

These in vitro and in situ studies showed that IL-1α, likely by TGFβ-unopposed autocrine or paracrine mechanisms, is an important modulator of TGFβ-promoted myofibroblast viability during corneal wound healing. The working hypothesis is that as the EBM is fully regenerated after fibrosis-generating epithelial-stromal injury, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 levels at TGF beta-dependent myofibroblasts drop to the point that IL-1α, produced by the myofibroblasts themselves and/or surrounding corneal fibroblasts, triggers myofibroblast apoptosis.

Opposing IL-1- and TGFβ-modulation of Expression of EBM Components

IL-1α and TGFβ also have opposing effects on the expression of some basement membrane components by stromal cells that participate in regeneration of the EBM.9,110 IL-1α or IL-1β upregulate perlecan mRNA expression in keratocytes, but not in corneal fibroblasts or myofibroblasts.110 Perlecan is a major component in the EBM that modulates TGFβ1, TGFβ2, PDGF AA, and PDGF BB penetration into the stroma and defective assembly of perlecan into the regenerating EBM has a role in the development of myofibroblasts associated with stromal fibrosis.9,110 IL-1α upregulates perlecan protein expression in keratocytes, whereas TGFβ1 significantly downregulates perlecan protein expression in keratocytes.110 TGFβ1 (or TGFβ3) also markedly downregulates nidogen-1 or nidogen-2 mRNA expression in keratocytes.110 Interestingly, in a PRK corneal fibrosis model in rabbits,110 perlecan protein expression was found to be increased in anterior stromal cells at one and two days after -9 diopters (D) PRK, but that subepithelial localization of perlecan was disrupted at 7 days and later time points after injury when myofibroblasts populated the anterior stroma in corneas that developed fibrosis.9,110

Thus, IL-1 likely promotes regeneration of the EBM after injury by upregulation of critical EBM components in keratocytes that survive the initial wave of apoptosis after corneal epithelial injury, or corneal fibroblasts that repopulate the subepithelial stroma. Conversely, TGF-β1 (or TGF-β3) may tend to impede EBM repair by downregulating production of components needed for EBM repair that are produced by keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts.

IL-1α and TGFβ Modulation of the Chemotaxis and Development of Fibrocytes After Epithelial-Stromal Injury

IL-1 Modulation of Cytokine Networking by Keratocytes/Corneal Fibroblasts After Injury

Within an hour after injury to the corneal epithelium or endothelium, large numbers of immune cells migrate into the corneal stroma from the limbal blood vessels.12,89,111–113 These cells are attracted into the stroma by IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF)α released by the injured epithelium and/or endothelium via both direct chemotaxis114 and a cascade effect known as cytokine networking.113,115 Thus, IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNFα bind to receptors on keratocytes that survive the wave of apoptosis in the anterior stroma—likely due to lower concentrations of IL-1 and TNFα that penetrated into the deeper stroma—and stimulates these keratocytes to produce chemokines such as CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP-1]; Fig. 4), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), CXCL5 (also called neutrophil-activating peptide or ENA-78), and monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor (MDNCF).89 These chemokines, and other cytokines like IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-17 upregulated in keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts,89 amplify the chemotactic effects on bone marrow-derived cells and draw lymphocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, fibrocytes, and other blood-derived cells into the corneal stroma to deal with the injury or infection in the cornea via this cytokine networking process.

Figure 4.

IL-1 mediated effects on stromal keratocytes after epithelial scrape injury in rabbits. (A) No CCL2 (also referred to as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 [MCP-1] or monocyte chemotactic and activating factor [MCAF]) protein was detected in keratocytes in unwounded rabbit corneas using immunocytochemistry. Some CCL2 was detected at the apical surface of the epithelium (arrow). (B) At 4 hours after epithelial scrape injury, upregulation of CCL2 protein was noted in keratocytes in the mid to posterior stroma (arrows). No CCL2 is detected in anterior keratocytes, likely because these cells are undergoing apoptosis in response to the epithelial scrape injury. Magnification 200 times. (C) Immunohistology for HGF shows that little HGF is detected in the unwounded rabbit cornea. The arrow points to the epithelial surface and s indicates the stroma. (D) At 48 hours after epithelial scrape injury, keratocytes in the mid-stroma and posterior stroma (small arrows) produce large amounts of HGF detected by IHC. Note little HGF is detected in the anterior stroma where keratocytes are undergoing apoptosis after epithelial scrape injury. Large arrows indicate healing epithelium that is binding HGF, likely from the keratocytes and lacrimal gland via tears, because corneal epithelial cells do not produce HGF themselves.131–133 Magnification 200 times. A and B republished from Hong, et al., Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001;42:2795-2803. C and D republished from Li et al., Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1996;37:727-739.

Fibrocytes are especially important bone marrow-derived cells in the fibrotic responses to severe epithelial-stromal injuries in the cornea due to their being one of the precursors to myofibroblasts.12,116 Studies in other organs have shown that when CCL2 binds functional CCR2 receptors on mouse or human fibrocytes, there is not only chemotaxis triggered by a gradient of CCL2 in the tissue, but also induction of fibrocyte proliferation and differentiation towards myofibroblasts.117,118 Conversely, fibroblasts do not express CCR2 receptors and do not respond to CCL2.

TGFβ modulation of Corneal Fibroblast and Fibrocyte Development Into Myofibroblasts

Once the fibrocytes arrive in the healing tissue, they are dependent on one or more TGFβ isoforms for survival and development into mature SMA-positive myofibroblasts, similar to corneal fibroblasts. Thus, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, in conjunction with PDGF, drive the development of myofibroblasts from keratocytes, and their progeny corneal fibroblasts, both in vitro15,100,119–123 and in situ.124 Similarly, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 drive the development of fibrocytes into mature SMA-positive myofibroblasts.125,126 Recent studies, however, have shown that corneal fibroblast-derived and fibrocyte-derived myofibroblasts are not equivalent cells, but likely cooperate in the generation of tissue fibrosis.127

Myofibroblasts are rarely seen in unwounded corneas.1,9 Interestingly, if TGFβ is overexpressed at high levels in the lens in vivo, myofibroblasts and fibrosis are generated in the overlying cornea.128 TGFβ1 is expressed in the normal unwounded corneal epithelium (see Fig. 3A) and endothelium (see Fig. 3C),9 and is present in the tears93,94 and aqueous humor.95–97 TGFβ2 is also present in tears,93 and at least at low levels in aqueous humor.95,96 Necessarily, there are systems in place to regulate TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 entry into the stroma in uninjured corneas to preclude needless keratocyte development into fibrosis-producing myofibroblasts. Studies demonstrated an apical epithelial barrier and epithelial basement membrane9,14,17,18,129 and Descemet's basement membrane8 regulate TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, and likely PDGF,130 entry into the stroma at sufficiently high levels to drive myofibroblast development from both keratocyte and fibrocyte precursors.

From immunocytochemistry studies of localization of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 proteins after PRK injury in rabbits, it's apparent an apical epithelial barrier modulates penetration of tear TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 into the full-thickness epithelium.9 This occurs possibly at the level of epithelial tight junctions. Thus, at 3 weeks after lower injury -4.5 D PRK in rabbits (see Fig. 3G), TGFβ1 localization is re-established in the superficial epithelium and few myofibroblasts typically develop. Conversely, at 3 weeks after high injury -9 D PRK (see Fig. 3H), there is full-thickness epithelial penetration of large amounts of TGFβ1, and large numbers of SMA-positive myofibroblasts develop in the anterior stroma.9 The specific components that contribute to the apical epithelial barrier that modulates TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 epithelial penetration need further investigation.

Some stromal cells—both SMA-positive myofibroblasts and SMA-negative cells—produced TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, but the amount of this stromal production is highly variable between different corneas in rabbits. The stromal SMA-negative cells producing TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 likely include keratocyte-derived corneal fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived cells, such as fibrocytes, but further work is needed to characterize these cells.9

More is known about the EBM and Descemet's basement membrane components that bind or block trans-EBM movement of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2. These include collagen type IV and perlecan.131–135 Perlecan is a major component in both of these corneal basement membranes and it produces a high negative charge due to three heparan sulfate side chains. Thus, perlecan also provides a nonspecific barrier to TGFβ penetration through either EBM or Descemet's basement membrane.132,134 Therefore, for sufficiently high and prolonged levels of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 needed to drive myofibroblast development from precursor cells to be available in the stroma, corneal injuries must include the EBM and/or Descemet's basement membrane.

TGFβ expression and localization patterns in corneal cells are very different in unwounded compared to wounded corneas (see Fig. 3), and also at different time points after wounding—depending on the status of EBM and Descemet's membrane. Injury to the corneal epithelium results in upregulation of TGFβ1 production by these cells9,105,106 and in tears.93,94 Changes in TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 expression in corneal endothelial cells after injury has apparently not been studied. If the EBM regenerates9 or Descemet's membrane is replaced surgically (because it rarely regenerates after severe injury),8,24 then TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 β levels in the stroma drop and mature myofibroblasts undergo apoptosis9 or revert to a precursor cell type (although there remains little data supporting the latter mechanism of myofibroblast disappearance). Death of the myofibroblasts is followed by repopulation of the fibrotic stroma with keratocytes. These keratocytes re-absorb and re-organize collagens and other extracellular matrix materials to restore corneal transparency.14,26 A drop in stromal TGFβ1 and/or TGFβ2 caused by a return to normal production of TGFβ1 by epithelial and/or endothelial cells, and possibly decreased TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 in tears, as well as regeneration of the epithelial barrier to penetration, the EBM and/or Descemet's basement membrane, facilitates the resolution of fibrosis.

After injury to the cornea, some stromal cells, which may include keratocytes, corneal fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and/or immune cells, may produce TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 (see Fig. 3).9 However, in most corneas, this stromal TGFβ appears to not be of sufficient magnitude or duration to drive myofibroblast generation (and their persistence) in the absence of damage and defective regeneration of the apical epithelial barrier, the EBM and/or Descemet's basement membrane.9 If, however, the basement membranes do not regenerate (or are replaced by transplantation), then myofibroblasts and fibrosis persist in the stroma due to ongoing penetration of TGFβ into the stroma at sufficient levels to maintain myofibroblast viability.8,9,17,100 Importantly, low levels of TGFβ are insufficient to drive corneal fibroblasts to develop into myofibroblasts.136

IL-1 Triggered Hepatocyte Growth Factor (and Keratinocyte Growth Factor) Production by Corneal Fibroblasts—HGF Inhibits Myofibroblast Viability Driven by TGFβ

Immediately after epithelial injury, keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts in the mid-stroma also begin to produce detectible hepatocyte growth factor (HGF; see Figs. 4C, 4D) and keratinocyte growth factor (KGF)—two classical mediators of stromal-epithelial interactions that regulate the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of the overlying epithelial cells to facilitate healing of the epithelium after injuries or infections.137–141 IL-1α and IL-1β are major up-regulators of HGF and KGF mRNA and protein production by keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts.139,140 Thus, injury to the epithelium triggers the release of IL-1, that then upregulates HGF and KGF production, that function to promote the healing of the injured epithelium.

However, HGF has also been shown to have an antifibrotic role, possibly in promoting myofibroblast apoptosis when TGFβ levels in the surrounding tissue drop to levels incompatible with survival.141–144 Thus, whereas IL-1 can directly promote myofibroblast apoptosis via autocrine or paracrine effects,90,91 it may also have an indirect effect in promoting HGF production by surrounding corneal fibroblasts and keratocytes that then drives myofibroblast apoptosis.

Opposing Effects of IL-1 and TGFβ on Expression of Metalloproteinases and Collagenases by Corneal Fibroblasts

Metalloproteinases and collagenases have a critical role in the stromal wound healing response because they are involved in the degradation of normal matrix during the early response to injury or infection, as well as maintenance and removal of the disordered extracellular matrix that is deposited in the stroma after injury, infections, or surgeries.33,34 IL-1 (or tumor necrosis factor alpha) upregulates the expression of metalloproteinases and collagenases by corneal stromal cells, and also regulates them in corneal epithelial cells.8,35,36 This upregulation of metalloproteinases and collagenases must be tightly regulated or severe damage to the corneal stroma could be produced by even trivial injuries or infections. As an example of this regulation, IL-1 receptor antagonist produced by corneal epithelial cells downregulates MMP-2 produced by corneal fibroblasts.15 A decrease in IL-1α and IL-1β released by the regenerated epithelium is likely another major regulator of the release of collagenases and matrix metalloproteinases by stromal cells, such as corneal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.

However, TGFβ may have opposing effects on the modulation of collagenases or metalloproteinases by corneal fibroblasts. West-Mays and coworkers145 showed that TGFβ1 inhibited collagenase production by rabbit corneal fibroblasts. TGFβ1 was also found to downregulate MMP-3 (stromelysin) expression in rat fibroblasts.146 In another in vitro study,147 this group found that TGFβ2 inhibited collagenase synthesis by rabbit corneal stromal cells. Finally, in yet another study by this group,148 the effects of IL-1α, IL-1β, or TGFβ1 on collagenase, stromelysin, and gelatinase were investigated in cultures of rabbit corneal fibroblasts. They found that recombinant human IL-1α or IL-1β increased collagenase, stromelysin, and gelatinase (both 92-kD and 72-kD). Conversely, they found that expression of collagenase and stromelysin were repressed, whereas expression of 72-kD gelatinase was increased, by treatment of corneal fibroblasts with recombinant human TGFβ1.

These studies suggest that in vivo IL-1 and TGFβ are likely to have opposing effects on the expression of key collagenases and metalloproteinases that are active in matrix degradation and regeneration after both nonfibrotic and fibrotic corneal injuries where both corneal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts produce disordered ECM.

Cross-Regulation Between the IL-1 and TGF Beta Systems

Many studies have shown that TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3 are the primary modulators of corneal scarring fibrosis in vitro and in situ in every organ studied.149–153 This is the case for the cornea, too. For example, Gupta and coworkers154 showed that targeted delivery of Smad7, the major intracellular negative modulator of TGFβ signaling, to the corneal stroma decreased stromal scarring after fibrosis-inducing injury. These investigators also showed that delivery of soluble TGFβ receptor II could attenuate TGFβ1-induced MFB development from corneal fibroblasts in vitro155 and that gene transfer of decorin, a natural proteoglycan inhibitor of TGFβ, inhibited the development of human corneal fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in vitro.156 Yang et al.157 showed that TGFβ-induced myofibroblast development is highly dependent on a positive feedback loop in which p-SMAD2-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) activates transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channel, TRPV1 causes activation of p38, the latter in turn further enhances the activation of SMAD2 to establish a recurrent loop that greatly extends the residency of the activated state of SMAD2 that drives myofibroblast development. Studies have also shown there are concentration-dependent effects of TGFβ1 on corneal wound healing.136 In addition, blockade of TGFβ receptor II markedly reduces the fibrotic response to corneal injury in mice in situ124 and TGFβ1 directly modulates the development of corneal fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in vitro.123

As was detailed earlier, TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and TGFβ3 signal through the same type I and type II receptors, and the same downstream signaling pathways, and yet the knockout phenotype of each isoform is different.156 The genes expressing TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 and have differing promoters that differentially regulate the expression of these genes in tissues during development, homeostasis, and the response to injury.159–161 TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 have differing expression patterns and likely different but overlapping roles during wound healing in the cornea compared to TGFβ3.105,106,162,163 TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 have profibrotic effects that include promotion of myofibroblast development from keratocyte and fibrocyte precursor cells and, conversely, in at least in some systems, TGFβ3 tends to have antifibrotic effects in adult animals.162–164

Supporting this role for TGFβ3, Karamichos and coworkers165 showed that the addition of TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 to human corneal fibroblasts cultured in a 3-dimensional construct stimulated the formation of a fibrotic matrix compared to control cultures, whereas the addition of TGFβ3 resulted in the production of a nonfibrotic matrix. This group also showed that PDGF receptor a was a key modulator of the differential effect of TGFβ1 (increases alpha-smooth muscle actin expression) compared to TGFβ3 (decreases alpha-smooth muscle actin expression) in human corneal fibroblasts—effects that would promote versus inhibit myofibroblast generation, respectively.163 They also showed that fibrillar collagen secreted by human corneal fibroblasts in the absence of TGFβ3 showed uniform parallel alignment in cultures.166 However, in the presence of TGFβ3, the collagen bundles made by the corneal fibroblasts had orthogonal layers indicative of the formation of lamellae in corneas. Finally, in cross-section projections, without TGFβ3, the corneal fibroblasts were flattened and largely localized on the Transwell membrane at the bottom of each well. Conversely, with TGFβ3, corneal fibroblasts were multilayered—as they are in corneas in situ. Construct thickness and collagen organization was also enhanced by TGFβ3.

In other very informative experiments,167 Zieske and colleagues also showed that TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 had similar early effects on the expression of fibrosis-related genes in human corneal fibroblasts. With longer exposure of 3 day's duration to each TGFβ isoform, however, there was differential expression of fibrosis-related genes in the human corneal fibroblasts—especially for genes that were involved in the modulation of ECM. For example, Smad7 (antagonist of signaling by TGF-type 1 receptor superfamily members) protein expression was significantly decreased by TGFβ1 but TGFβ3 had no significant effect on Smad7 protein expression. Thrombospondin-1 protein production in human corneal fibroblasts was significantly increased by TGFβ3 (2.5-fold higher than controls), whereas TGFβ1 had no significant effect on thrombospondin-1 protein expression in corneal fibroblasts. Collagen type I protein production was significantly increased and Smad3 (a TGF-beta receptor cytoplasmic protein that is responsible for downstream cellular signaling of the TGF-beta receptors) was dramatically decreased by both TGFβ1 and TGFβ3. Of the 84 fibrosis-related genes analyzed in corneal fibroblasts in this study, however, after 3 days of exposure to TGFβ1 or TGFβ3, only 5 of the 84 genes were upregulated by TGFβ3 compared to TGFβ1—MMP1, plasminogen activator urokinase, integrin alpha-1, thrombospondin-1, and IL-1α (which was 2.7 times the fold upregulated by TGFβ3 compared to TGFβ1). Both TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 upregulated IL-1α after 4 hours of exposure compared to controls (2.6 times and 2.0 times, respectively), but were not significantly different from each other. No effect of TGFβ1 or TGFβ3 on IL-1α expression was seen at 3 days. These results show, however, that TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 do modulate the expression of IL-1α and IL-1β. What is perhaps most surprising about this study is how few differences in the expression of fibrotic genes in corneal fibroblasts were found between TGFβ1 and TGFβ3—only 1 difference in the 84 genes and 5 differences in the 84 genes evaluated at 4 hours and 3 days, respectively. Thus, 83 of 84 genes and 79 of 84 fibrotic genes were similarly regulated by TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 in corneal fibroblasts after 4 hours or 3 days, respectively. In the author's thinking, the great similarity in modulation by TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 calls into question the rather simple labels of “profibrotic” versus antifibrotic” for these two TGFβ isoforms. This is especially the case if one looks at specific fibrotic genes that were similarly regulated by the two isoforms in this study. For example, the most profoundly downregulated gene in corneal fibroblasts by both TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 after 3 days was HGF (-73.5 times and -56 times downregulated, respectively). If TGFβ3 were truly antifibrotic, perhaps upregulation of HGF by this isoform would have been expected given recent studies showing HGF has an anti-fibrotic effect on myofibroblast viability.141–143 Perhaps this greater similarity than difference in the modulation of fibrotic genes by TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 provides one explanation for why TGFβ3 failed to modulate scarring in skin in phase III clinical trials that included 350 adult patients, if skin fibroblasts have similar responses to the TGFβ isoforms as corneal fibroblasts.168 Thus, TGFβ3 appears to have fibro-modulatory differences from TGFβ1, but to not be truly “antifibrotic,” which was always difficult to explain based on the isoforms signaling via the same receptors and sharing so many similarities in the signal transduction pathways that are activated.56–75

In other organs, IL-1 isoforms have been shown to differentially modulate the expression of TGFβ isoforms. Thus, in human articular chondrocytes in vitro, IL-1β downregulated TGFβ1 mRNA expression but upregulated TGFβ3 isoform mRNA expression.169 Similarly, IL-1β selectively induced TGFβ3 protein synthesis but reduced synthesis of the TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 proteins in articular chondrocytes. Li and Tseng170 found IL-1βdid not affect TGFβ1 expression in human corneal or limbal fibroblasts. Otherwise, there has been little investigation of potential effects of the IL-1 isoforms on the expression of TGFβ isoforms, or their receptors, in corneal stromal cells, but such studies could be revealing based on the cross-talk between these two systems in other organs.

Summation

Thus, in some respects, IL-1α and IL-1β have complementary roles to TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 in promoting the development of myofibroblasts after epithelial-stromal injuries that produce fibrosis. However, other functions of IL-1α and IL-1β seemingly oppose TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 effects in promoting fibrosis.

Corneal Cellular Functions Regulated by IL-1 Without Known TGFβ Involvement

The Keratocyte Apoptosis Response to Epithelial or Endothelial Corneal Injury Via Modulation of the Fas-Fas Ligand System

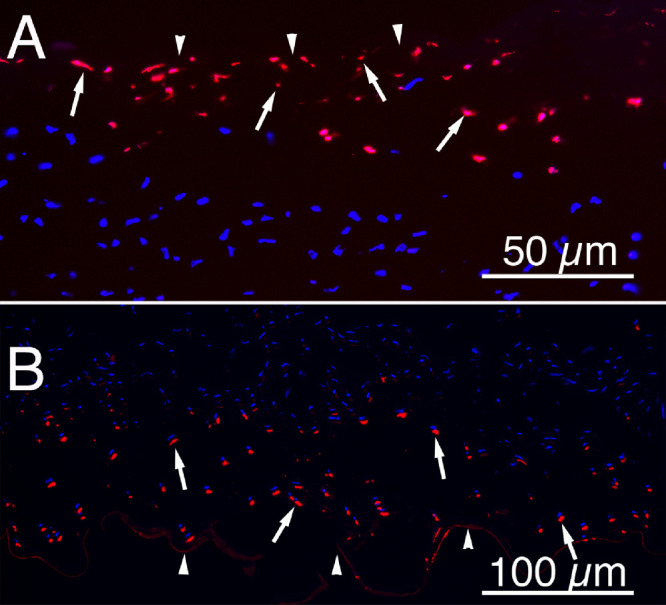

Immediately after injury to the epithelium5 or endothelium7 underlying or overlying, respectively, keratocytes undergo apoptosis (Fig. 5). Studies have shown that this programmed cell death is likely mediated via activation of the Fas-Fas ligand system—with high concentrations of epithelial and/or endothelial IL-1 penetrating into the adjacent stroma, binding IL-1 receptors on keratocytes, and stimulating production of autocrine Fas ligand.55,171 Because keratocytes constitutively produce the receptor Fas,55,171 this rapid increase in Fas ligand stimulates the cells to undergo “autocrine suicide” apoptosis. This process initiates the stromal wound healing response after either epithelial and/or endothelial injury. Presumably, this keratocyte apoptosis is IL-1 concentration dependent, since it extends only 30 to 50 µm depth into the stroma from either the epithelium and/or endothelium that is injured (see Fig. 5).

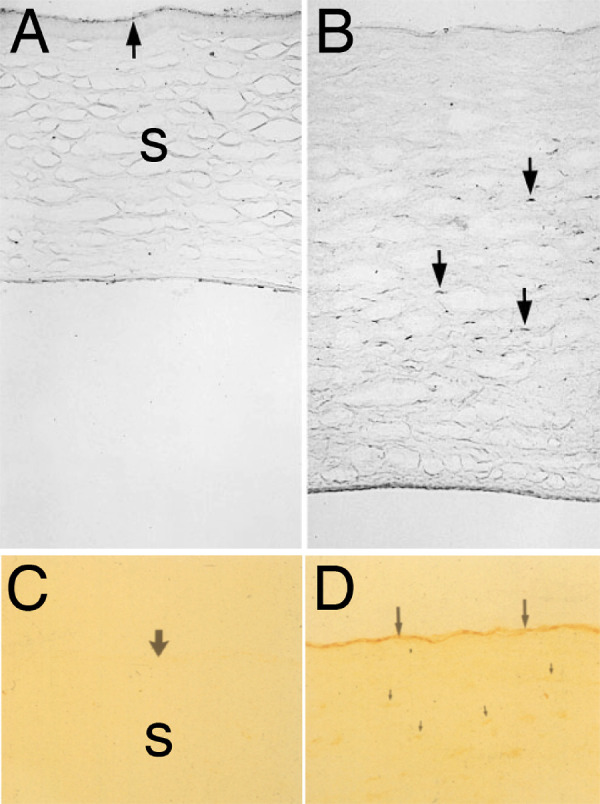

Figure 5.

Keratocyte apoptosis in response to epithelial or endothelial scrape injury. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL, red) assay at 4 hours after mechanical epithelial scrape injury to (A) rabbit epithelium or (B) rabbit endothelium produced a wave of keratocyte apoptosis (arrows) in the stroma adjacent to the site of injury. Arrowheads in A indicate the anterior stromal surface. Arrowheads in B indicate Descemet's membrane. The apoptotic cell death in both injuries was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (not shown).5,7 Blue is DAPI staining of nuclei in both apoptosis and non-apoptotic keratocytes. Magnification in A 200 times and magnification in B 100 times.

As of yet, there have been no reports of TGFβ influencing the keratocyte apoptosis response to epithelial injury.

Conclusions

The specific effects of the IL-1 and TGFβ isoforms on corneal stromal cells—including keratocytes, corneal fibroblasts, fibrocytes, and myofibroblasts—likely depends on the cells’ overall milieu of growth factors, cytokines (including IL-1α and IL-1β), integrins, and other modulators, as well as the status of the associated ECM, including adjacent corneal basement membranes, and the expression of the IL-1 and TGFβ receptor family members in the cells.

The IL-1 cytokine-receptor system modulates both early and late events in the corneal responses to injuries, including the early keratocyte apoptosis response and late myofibroblast apoptosis. IL-1 also regulates the expression of HGF and KGF by keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts that control corneal epithelial healing, as well as the expression of collagenases and metalloproteinases needed for breakdown and remodeling of stromal matrix. IL-1, also a controller of cytokine networking whereby corneal fibroblasts produce chemokines that modulate the influx of bone marrow-derived cells, including fibrocytes, fights infectious agents and contributes to the development of myofibroblasts.

The TGFβ growth factor-receptor system is equally important in modulating the development of keratocyte-derived corneal fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived fibrocytes into myofibroblasts. TGFβs also maintain mature myofibroblasts once they develop, and removal of a requisite source of the TGFβs leads to myofibroblast apoptosis.

In some functions, such as myofibroblast viability, basement membrane component production, and collagenase/metalloproteinase expression, the two systems oppose each other to finely tune the overall corneal healing response. In other functions, such as promoting the early development of myofibroblasts after epithelial-stromal injuries, the two systems work hand in hand to promote the development of corneal fibrosis. Thus, the two systems function in coordination as “co-master regulators” of the overall wound healing response to a particular corneal injury or infection. There remains a great deal of work to be done to better understand the cross-talk that likely occurs between the IL-1 and TGFβ systems in corneal homeostasis, wound healing, and fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Department of Defense grant VR180066, US Public Health Service Grants RO1EY10056 (S.E.W.) and P30-EY025585 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY.

Disclosure: S.E. Wilson, None

References

- 1. Mohan RR, Hutcheon AEK, Choi R, et al. Apoptosis, necrosis, proliferation, and myofibroblast generation in the stroma following LASIK and PRK. Exp Eye Res. 2003; 76: 71–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Generali E, Cantarini L, Selmi C.. Ocular involvement in systemic autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015; 49: 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suzuki T, Ohashi Y.. Corneal endotheliitis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008; 23: 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilson SE. Corneal wound healing. Exp Eye Res. 2020; 197: 108089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilson SE, He Y-G, Weng J, et al. Epithelial injury induces keratocyte apoptosis: hypothesized role for the interleukin-1 system in the modulation of corneal tissue organization and wound healing. Exp Eye Res. 1996; 62: 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wagoner MD. Chemical injuries of the eye: current concepts in pathophysiology and therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997; 41: 275–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Medeiros CS, Lassance L, Saikia P, Wilson SE.. Posterior stromal keratocyte apoptosis triggered by mechanical endothelial injury and nidogen-1 production in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 2018; 172: 30–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Medeiros CS, Saikia P, de Oliveira RC, Lassance L, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE.. Descemet's membrane modulation of posterior corneal fibrosis. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2019; 60: 1010–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Oliveira RC, Tye G, Sampaio LP, et al. TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 proteins in corneas with and without stromal fibrosis: delayed regeneration of apical epithelial growth factor barrier and the epithelial basement membrane in corneas with stromal fibrosis. Exp Eye Res 2021; 202: 108325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fini ME. Keratocyte and fibroblast phenotypes in the repairing cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999; 18: 529–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ljubimov AV, Saghizadeh M.. Progress in corneal wound healing. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015; 49: 17–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lassance L, Marino GK, Medeiros CS, Thangavadivel S, Wilson SE.. Fibrocyte migration, differentiation and apoptosis during the corneal wound healing response to injury. Exp Eye Res. 2018; 170: 177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu CY, Kao WW.. Corneal epithelial wound healing. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015; 134: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marino GK, Santhiago MR, Santhanam A, et al. Epithelial basement membrane injury and regeneration modulates corneal fibrosis after pseudomonas corneal ulcers in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2017; 161: 101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jester JV, Huang J, Petroll WM, Cavanagh HD.. TGF beta induced myofibroblast differentiation of rabbit keratocytes requires synergistic TGF beta, PDGF and integrin signaling. Exp Eye Res. 2002; 75: 645–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilson SE. Corneal myofibroblasts and fibrosis. Exp Eye Res. 2020; 201: 108272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Torricelli AAM, Singh V, Agrawal V, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE.. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of epithelial basement membrane repair in rabbit corneas with haze. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 4026–4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Torricelli AAM, Singh V, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE.. The corneal epithelial basement membrane: structure, function and disease. Invest Ophth Vis Sci 2013; 54: 6390–6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilson SE, Torricelli AAM, Marino GK.. Corneal epithelial basement membrane: structure, function and regeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2020; 194: 108002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilson SE, Medeiros CS, Santhiago MR.. Pathophysiology of corneal scarring in persistent epithelial defects after PRK and other corneal injuries, J Ref Surg. 2018; 34: 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilson SE, Marino GK, Torricelli AAM, Medeiros CS.. Corneal fibrosis: injury and defective regeneration of the epithelial basement membrane. A paradigm for fibrosis in other organs? Matrix Biology. 2017; 64: 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saikia P, Thangavadivel S, Lassance L, Medeiros CS, Wilson SE.. IL-1 and TGFβ2; modulation of epithelial basement membrane components perlecan and nidogen production by corneal stromal cells. Invest Ophth Vis Sci . 2018; 59: 5589–5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jester JV, Moller-Pedersen T, Huang J, et al. The cellular basis of corneal transparency: evidence for 'corneal crystallins'. J Cell Sci. 1999; 112: 613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Medeiros CS, Marino GK, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE.. The corneal basement membranes and stromal fibrosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018; 59: 4044–4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilson SE. Coordinated modulation of corneal scarring by the epithelial basement membrane and Descemet's basement membrane. J Refract Surg. 2019; 35: 506–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hassell JR, Cintron C, Kublin C, Newsome DA.. Proteoglycan changes during restoration of transparency in corneal scars. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983; 222: 362–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilson SE, Chaurasia SS, Medeiros FW.. Apoptosis in the initiation, modulation and termination of the corneal wound healing response. Exp Eye Res. 2007; 85: 305–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mondino BJ. Inflammatory diseases of the peripheral cornea. Ophthalmology. 1988; 95: 463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson SE, Lee WM, Murakami C, Weng J, Moninger GA.. Mooren-type hepatitis C virus-associated corneal ulceration. Ophthalmology. 1994; 101: 736–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palomo J, Dietrich D, Martin P, Palmer G, Gabay C.. The interleukin (IL)-1 cytokine family–balance between agonists and antagonists in inflammatory diseases. Cytokine. 2015; 76: 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yazdi AS, Ghoreschi K.. The interleukin-1 family. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016; 941: 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004; 430: 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Broz P, Dixit VM.. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016; 16: 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guma M, Ronacher L, Liu-Bryan R, Takai S, Karin M, Corr M.. Caspase 1-independent activation of interleukin-1beta in neutrophil-predominant inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 60: 3642–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Joosten LA, Netea MG, Fantuzzi G, et al. Inflammatory arthritis in caspase 1 gene-deficient mice. contribution of proteinase 3 to caspase 1-independent production of bioactive interleukin-1beta. Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 60: 3651–3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Afonina IS, Tynan GA, Logue SE, et al. Granzyme B-dependent proteolysis acts as a switch to enhance the proinflammatory activity of IL-1α. Mol Cell. 2011; 44: 265–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lefrançais E, Roga S, Gautier V, et al. IL-33 is processed into mature bioactive forms by neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012; 109: 1673–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hazlett LD. Role of innate and adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of keratitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005; 13: 133–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yu FS, Hazlett LD.. Toll-like receptors and the eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 1255–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hazlett LD, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, et al. IL-33 shifts macrophage polarization, promoting resistance against Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 1524–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li J, Zhang L, Chen X, et al. Pollen/TLR4 innate immunity signaling initiates IL-33/ST2/Th2 pathways in allergic Inflammation. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 36150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Walsh PT, Fallon PG.. The emergence of the IL-36 cytokine family as novel targets for inflammatory diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018; 1417: 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jensen LE. Interleukin-36 cytokines may overcome microbial immune evasion strategies that inhibit interleukin-1 family signaling . Sci Signal. 2017; 10: eaan3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gao N, Me R, Dai C, Seyoum B, Yu FX.. Opposing effects of IL-1Ra and IL-36Ra on innate immune response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in C57BL/6 mouse corneas. J Immunol. 2018; 201: 688–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Imai Y, Hosotani Y, Ishikawa H, et al. Expression of IL-33 in ocular surface epithelium induces atopic keratoconjunctivitis with activation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in mice. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 10053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dripps DJ, Brandhuber BJ, Thompson RC, Eisenberg SP.. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist binds to the 80-kDa IL-1 receptor but does not initiate IL-1 signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1991; 266: 10331–10336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Arend WP, Welgus HG, Thompson RC, Eisenberg SP.. Biological properties of recombinant human monocyte-derived interleukin 1 receptor antagonist. J Clin Invest. 1990; 85: 1694–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Amparo F, Dastjerdi MH, Okanobo A, et al. Topical interleukin 1 receptor antagonist for treatment of dry eye disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013; 131: 715–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bottin C, Fel A, Butel N, et al. Anakinra in the treatment of patients with refractory scleritis: a pilot study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018; 26: 915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yamada J, Dana MR, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S.. Local suppression of IL-1 by receptor antagonist in the rat model of corneal alkali injury. Exp Eye Res. 2003; 76: 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dana MR, Yamada J, Streilein JW.. Topical interleukin 1 receptor antagonist promotes corneal transplant survival. Transplantation. 1997; 63: 1501–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McMahan CJ, Slack JL, Mosley B, et al.. A novel IL-1 receptor, cloned from B cells by mammalian expression, is expressed in many cell types. EMBO J. 1991; 10: 2821–2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boraschi D, Italiani P, Weil S, Martin MU.. The family of the interleukin-1 receptors. Immunol Rev. 2018; 281: 197–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guo C, Yang XG, Wang F, Ma XY.. IL-1α induces apoptosis and inhibits the osteoblast differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells through the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways. Int J Mol Med. 2016; 38: 319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mohan RR, Liang Q, Kim W-J, Helena MC, Baerveldt F, Wilson SE.. Apoptosis in the cornea: further characterization of Fas-Fas ligand system. Exp Eye Res. 1997; 65: 575–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Morikawa M, Derynck R, Miyazono K.. TGF-β and the TGF-β family: context-dependent roles in cell and tissue physiology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol . 2016; 8: a021873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Finnson KW, McLean S, Di Guglielmo GM, Philip A.. Dynamics of transforming growth factor beta signaling in wound healing and scarring. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013; 2: 195–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Brunner G., Blakytny R.. Extracellular regulation of TGF-β activity in wound repair: growth factor latency as a sensor mechanism for injury. Thromb Haemost. 2004; 92: 253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yu Q., Stamenkovic I.. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-β and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev . 2000; 14: 163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Annes JP., Rifkin DB., Munger JS.. The integrin αVβ6 binds and activates latent TGFβ3. FEBS Lett. 2002; 511: 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Budi EH, Xu J., Derynck R.. Regulation of TGF-β receptors. Methods Mol Biol. 2016; 1344: 1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hata A, Chen YG.. TGF-beta signaling from receptors to Smads. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016; 8: a022061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Role of Smads in TGF beta signaling. Cell Tissue Res. 2012; 347:21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vander Ark A, Cao J, Li X.. TGF-β receptors: in and beyond TGF-β signaling. Cell Signal. 2018; 52: 112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Morén A, et al. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 1997; 389: 631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Inoue Y, Imamura T.. Regulation of TGF-beta family signaling by E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cancer Sci. 2008; 99: 2107–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Inoue Y, Imamura T.. Regulation of TGF-beta family signaling by E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cancer Sci. 2008; 99: 2107–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mu Y, Gudey SK, Landstrom M.. Non-Smad signaling pathways. Cell Tissue Res. 2012; 347: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang YE. Non-Smad signaling pathways of the TGF-β family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017; 9: a022129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Derynck R, Zhang YE.. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003; 425: 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Pepin MC, et al. Functional roles for the cytoplasmic domain of the type III transforming growth factor beta receptor in regulating transforming growth factor beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001; 276: 24627–24637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sarraj MA, Escalona RM, Umbers A, et al. Fetal testis dysgenesis and compromised Leydig cell function in TGFBR3 (beta glycan) knockout mice. Biol Reprod. 2010; 82: 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Martinez-Hackert E, Sundan A, Holien T.. Receptor binding competition: a paradigm for regulating TGF-β family action. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020; S1359-6101: 30206–30209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Aykul S, Martinez-Hackert E.. Transforming growth factor-beta family ligands can function as antagonists by competing for type II receptor binding. J Biol Chem. 2016; 291: 10792–10804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chang C. Agonists and antagonists of TGF-β family ligands. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016; 8: a021923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wilson SE, Lloyd SA.. Epidermal growth factor and its receptor, basic fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor beta-1, and interleukin-1 alpha messenger RNA production in human corneal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991; 32: 2747–2756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wilson SE, He YG, Lloyd SA. EGF, EGF receptor, basic FGF, TGF beta-1, and IL-1 alpha mRNA in human corneal epithelial cells and stromal fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci . 1992; 33: 1756–1765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wilson SE, Schultz GS, Chegini N, Weng J, He YG.. Epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, transforming growth factor beta, acidic fibroblast growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and interleukin-1 proteins in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 1994; 59: 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Malik A, Kanneganti TD.. Function and regulation of IL-1α in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2018; 281: 124–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. West-Mays JA, Strissel KJ, Sadow PM, Fini ME.. Competence for collagenase gene expression by tissue fibroblasts requires activation of an interleukin 1 alpha autocrine loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995; 92: 6768–6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]