Abstract

The purpose of this review was to update the complication profile of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) post-2010, given greater procedural familiarity, improved learning curves, enhanced implant designs, and increased attention to the nuances of patient selection. Three electronic databases were searched and screened in duplicate from 1 January 2010 to 16 December 2018 based on predetermined criteria. Twenty-two studies examining 1455 patients (26% male; mean age: 73.4 ± 3.6; mean follow-up: 23.4 ± 14.3 months) were reviewed. Post-operative motion ranged a mean 122.4° ± 11.5° flexion, 109° ± 19.4° abduction, and 33° ± 11.2°/41° ± 5° external/internal rotation. Post-operative mean Constant score was 58.9 ± 10.1, American Shoulder Elbow Surgeon score was 73.4 ± 6.1, Simple Shoulder Test score was 63.5 ± 6.5, and a Visual Analog Scale pain score was 1.6 ± 0.9. The overall complication rate was 18.2% and major complication rate was 15.4%. Compared to pre-2010, the overall complication rate of 18.2% is lower than previous rates of 19%–68%, with the rate of “major” complications dropping three-fold from 15.4% to 4.6%. The data suggest that rTSA is a safe and efficacious alternative to aTSA and HA, and the “stale” nature of previous complication profiles are points fundamental to perioperative discussions surrounding rTSA.

Keywords: reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, complications, outcomes, systematic review

Introduction

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) was introduced in the 1970s in response to increasingly unsatisfactory clinical outcomes regarding pain and shoulder function in the treatment of rotator cuff tear arthropathy with hemiarthroplasty (HA) or anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (aTSA).1 Primary rTSA was developed as a surgical technique to compensate for severe rotator cuff deficiency by using a convex glenoid and concave humeral design. In comparison to aTSA, rTSA provided additional stability in rotator cuff-deficient patients. If the rotator cuff is deficient in patients undergoing aTSA, then the unopposed action of the deltoid promotes superior migration of the humeral head, resulting in device and surgical failure.2–8 Since the introduction of rTSA, modifications have been made to the original design, but the overall biomechanical concepts and considerations have remained fairly consistent. Primary rTSA was originally adopted in Europe in the 1980s but was not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States until 2003.8

The overall success of the reverse prosthesis is a contributing factor to the substantial growth in the number of shoulder arthroplasties performed worldwide.3,9,10 Within the United States patient population specifically, approximately one third of all shoulder arthroplasty procedures performed are primary rTSA.8 Within that group, the major indication for primary rTSA was rotator cuff tear arthropathy, but there is an increasing variety of indications for rTSA that now include but are not limited to: acute and delayed proximal humeral fractures11; rheumatoid arthritis; fracture malunion and non-union; tumor; fixed glenohumeral dislocation12; and severe glenoid bone loss.13 This increase in primary rTSA in the United States alone suggests that this procedure is becoming a more frequently discussed surgical option for managing conditions such as rotator cuff arthropathy and humeral fractures that were once poorly managed with HA or anatomic bipolar arthroplasty.1 The learning curve for rTSA is generally cited as 40 cases.14,15 With time, increasing mastery of the technique, and a more nuanced understanding of its advantages and limitations, the list of acceptable indications has continued to expand.

Critics of its increasing popularity among surgeons often point to the high complication rates associated with rTSA which has been reported at 19%–68%.16,17 These numbers, however, may not reflect the true complication profile with current techniques as they are based largely on early studies. Accordingly, it is expected that the complication rate of primary rTSA will decrease to more acceptable levels with increased familiarity and frequency of the prosthesis as well as improved prosthetic design. Although many systematic reviews have investigated the biomechanics, complications, and indications of primary rTSA, the literature is sparse concerning the indications, outcomes, complication profiles with more recent designs, and wide-spread application of the technique. The objective of this review was to assess and update the complication profile of rTSA post-2010, given greater procedural familiarity, improved learning curves, enhanced implant designs, and increased attention to the nuances of patient selection. The primary objective encompasses capturing data that more accurately reflect current practice among surgeons who become more experienced after the initial learning curve years, and with more current prosthetic designs. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that for these reasons, the complication rate of primary rTSA will be significantly less than previously reported.

Methods

Search strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used in the design of this study.18 Three online databases (PubMed, Medline, and Embase) were searched for literature published between 1 January 2010 and 16 December 2018 regarding clinical outcomes and complications of primary rTSA.

Study screening

The research question and eligibility criteria were established prior to searching the databases. The screening of studies was defined by pre-determined criteria including English-language publications and human studies of all levels of evidence that examined the outcomes and complications of primary rTSA in patient populations after 1 January 2010.

Two reviewers (RC, FS) independently screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the identified studies in duplicate. At the level of title and abstract screening, any discrepancies in inclusion/exclusion were carried to the next round of screening. Any discrepancies that existed between reviewers at the full text stage were discussed between reviewers to resolve the discrepancy, with residual discrepancies resolved by a third, senior reviewer (DdS). References to each included study were screened to capture any publications that may have eluded the original search queries.

Quality assessment of included studies

A quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) criteria. Each of the 12 items in the MINORS criteria is scored between 0 and 2, with maximum scores of 12 and 24 for non-comparative and comparative studies, respectively.19

Data abstraction

Relevant clinical indications, outcomes, and complications were abstracted from eligible studies including demographic information when reported in the included studies. Clinical range of motion (ROM) data abstracted included forward flexion, abduction, external rotation, and internal rotation. Clinical outcomes included Constant, American Shoulder Elbow Surgeon (ASES), Simple Shoulder Test (SST), and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Pain scores. Complications abstracted included scapular notching, peri-glenoid radiolucency, heterotopic ossification (HO), dislocation, infection, humeral stem loosening, acromion/scapular spine fracture, neurological complications, and periprosthetic fracture. In this review, the absence of a reported complication was not necessarily viewed the same as the complication not occurring. Complications were graded using a modified Clavien-Dindo surgical complication scale specific for orthopedics. Classifications were graded on a scale of increasing severity from I to V.20 Complications graded I were further considered as “minor” complications. Complications graded II and III were considered “major” complications and surgical intervention was necessary for elevating a type II complication to a type III complication. Grade IV complications were characterized by the necessity for life-saving surgical intervention and the only grade V complication was death.

Statistical analysis

An unweighted kappa (κ) was calculated at each stage of screening for evaluating the level of agreement between reviewers (RC, FS). Level of agreement was categorized prior to the beginning of the literature search using the following κ-score criteria: a κ-score > 0.61 indicated substantial agreement; a score of 0.21 to 0.60 indicated moderate agreement; and scores of < 0.20 indicated slight agreement.21 Results documented across multiple studies were averaged and reported as mean. Overall complication rate was calculated as the dividend of the total number of complications and the total number of patients. Due to individual study heterogeneity, a formal meta-analysis was not performed.

Results

Study characteristics and quality

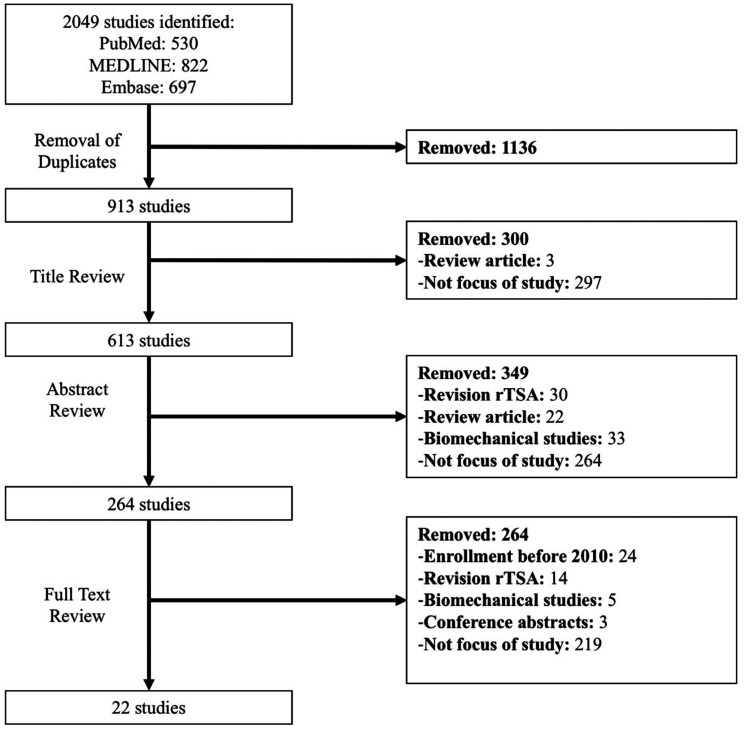

The initial literature search returned 913 studies, of which 22 satisfied inclusion criteria (Figure 1). There was a substantial level of agreement between reviewers at title (κ = 0.741; 95% CI: 0.69, 0.79), abstract (κ = 0.854; 95% CI: 0.81, 0.89), and full text screening stages (κ = 1; 95% CI: 1 to 1). The included non-comparative and comparative clinical studies were of moderate quality, as indicated by a mean MINORS score of 8.7 ± 2.7 (max 12) and 17.4 ± 3.0 (max 24), respectively.

Figure 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram demonstrating the process for systematic review of the literature regarding clinical outcomes and complications of primary rTSA performed after 2010.

The complete patient demographics from the included studies are reported in Table 1. Briefly, this review examines data across a total 1455 patients (1425 shoulders), of mean age 73.4 ± 3.6 years, 26% male, and followed up for a mean 23.4 ± 14.3 months post-operatively. Three studies did not report patient age or sex.22–24 One study did not report patient follow-up.22 Indications for primary rTSA included rotator cuff tear arthropathy (34.4%), acute humeral fracture (32.9%), osteoarthritis (10.6%), massive rotator cuff tear (7.7%), and fracture sequelae (2.7%). Indications for 762 patients were not reported (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics of included studies.

| Authors | Year | LOE | # of Ptsa | Follow-up | Age (years) | Male (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chalmers et al.64 | 2014 | III | 9 | 1.2 years | 77 ± 6 | 22 |

| Formaini et al.48 | 2015 | IV | 25 | 17 months | 77 (63–88) | 32 |

| Frank et al.65 | 2018 | III | 243 | 42.8 ± 16.4 | 66.4 ± 9.5 | 47 |

| Uzer et al.47 | 2017 | III | 33 | 16.8 months | 72.5 (65–82) | 36 |

| Izquierdo-Fernández et al.66 | 2017 | IV | 29 | 4 years | 78.9 ± 2.9 | 17 |

| Jonušas et al.67 | 2017 | IV | 27 | 45 months (39–48) | 67.5 ± 7.3 | 26 |

| Jorge-Mora et al.49 | 2018 | IV | 58 | 26 months (6–56) | 76.9 | 5 |

| Kirzner et al.68 | 2018 | III | 40 | 20 months (12–48) | 74.8 | 23 |

| Lowe et al.46 | 2018 | II | 30 | 2 weeks | 75.5 ± 5.3 | 17 |

| Merolla et al.76 | 2018 | III | 74 | 32 months (24–49) | 75.2 (55–91) | 31 |

| Padegimas et al.b,22 | 2016 | IV | 393 | – | – | – |

| Padegimas et al.69 | 2018 | IV | 14 | 4.1 years | 68.5 ± 11.0 | 50 |

| Parisien et al.57 | 2016 | II | 12 | 2 weeks | 69.3 (50–87) | 33 |

| Raiss et al.70 | 2018 | IV | 77 | 28 months (24–48) | 72 (50–91) | – |

| Sanchez-Sotelo et al.50 | 2018 | IV | 90 | 2 years | 69.3 ± 9.6 | 46 |

| Schnetzke et al.24 | 2017 | II | 24 | 25 months (20–35) | – | – |

| Thomasson et al.23 | 2015 | IV | 57 | 15 months | – | – |

| Torrens et al.71 | 2016 | I | 81 | 2 years | 75.7 ± 6.25 | 14 |

| Updegrove et al.72 | 2018 | IV | 37 | 2 years | 74.1 ± 8.7 | 30 |

| Verdano et al.73 | 2018 | III | 32 | 14.3 months | 77.4 | 25 |

| Yoon et al.74 | 2017 | III | 35 | 16.5 ± 5.9 months | 74.8 ± 4.2 | 23 |

| Zilber et al.75 | 2018 | III | 35 | 2 years | 73 | 20 |

| Total | 1455 | 23.4 ± 14.3 Months | 73.5 ± 3.7 Years | 26 |

LOE: level of evidence.

aNo bilateral shoulder replacements were performed.

bStudy combines primary and revision rTSA in reporting demographics and does not report primary rTSA demographics alone.

Table 2.

Indications of the rTSA.a

| Authors | Year | Total CASES | Fx | CTA | FS | MRCT | OA | RA | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chalmers et al.64 | 2014 | 9 | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Formaini et al.48 | 2015 | 25 | 25 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Frank et al.65 | 2018 | 243 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Uzer et al.47 | 2017 | 33 | 33 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Izquierdo-Fernández et al.66 | 2017 | 29 | 15 | 14 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jonušas et al.67 | 2017 | 27 | 27 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jorge-Mora et al.49 | 2018 | 58 | 58 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kirzner et al.68 | 2018 | 40 | 10 | 10 | – | – | 12 | – | 8 |

| Lowe et al.46 | 2018 | 30 | – | 12 | – | – | 18 | – | – |

| Merolla et al.76 | 2018 | 74 | – | 74 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Padegimas et al.b,22 | 2016 | 393 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Padegimas et al.69 | 2018 | 14 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 |

| Parisien et al.57 | 2016 | 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Raiss et al.70 | 2018 | 77 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sanchez-Sotelo et al.50 | 2018 | 90 | – | 13 | 2 | 39 | 32 | 2 | 2 |

| Schnetzke et al.24 | 2017 | 24 | – | 17 | 5 | – | 2 | – | – |

| Thomasson et al.23 | 2015 | 57 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Torrens et al.71 | 2016 | 81 | 17 | 55 | 9 | – | – | – | – |

| Updegrove et al.72 | 2018 | 37 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Verdano et al.73 | 2018 | 32 | 32 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yoon et al.74 | 2017 | 35 | – | 25 | – | 10 | – | – | – |

| Zilber et al.75 | 2018 | 35 | 2 | 19 | 3 | – | 10 | – | 1 |

| Total | 693 | 228 | 239 | 19 | 49 | 74 | 2 | 25 | |

| % | 32.9 | 34.5 | 2.7 | 7.1 | 10.7 | 0.2 | 3.6 | ||

Fx: proximal humeral fracture; CTA: cuff tear arthropathy; FS: fracture sequelae; MRCT: massive rotator cuff tear; OA: osteoarthritis; RA: rheumatoid arthritis.

aIndications for rTSA were not reported.

Complications

The complications of primary rTSA are listed in Table 3. The overall complication rate reported was 18.2%. The “minor” complications (grade I) reported in descending frequency were scapular notching (22.5%; 115 of 512 patients), radiographic HO (14.4%; 39 of 270 patients), peri-glenoid radiolucency (9.5%; 26 of 273 patients), and miscellaneous complications (5.1%; 18 of 355 patients). The “major” complications not requiring surgical intervention and treated conservatively (grade II) included: neuropraxia (2.7%; 9 of 330 patients); and acromion fracture (2.3%; 12 of 532 patients). The “major” complications necessitating surgical intervention and revision included periprosthetic humeral stem loosening (5.5%; 14 of 256 patients), periprosthetic humeral fracture (1.6%; 4of 257 patients), deep infection (1.6%; 13 of 796 patients), dislocation (1.3%; 15 of 1141 patients), and cubital tunnel syndrome (CuTS) (0.4%; 1 of 256 patients). No grade IV or V complications were reported across any studies (Table 4).

Table 3.

Range of motion after rTSA.

| Authors | Year | Total | Forward Flexion | Abduction | ER | IR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chalmers et al.64 | 2014 | 9 | 133° | – | 41° | 46° |

| Formaini et al.48 | 2015 | 25 | 117° | 86° | 29° | L1–L3 |

| Frank et al.65 | 2018 | 243 | 132° | – | 46° | – |

| Uzer et al.47 | 2017 | 33 | 113° | 91° | 42° | 41° |

| Izquierdo-Fernández et al.66 | 2017 | 29 | – | – | – | – |

| Jonušas et al.67 | 2017 | 27 | 117° | – | – | – |

| Jorge-Mora et al.49 | 2018 | 58 | 100° | 99° | 21° | 36° |

| Kirzner et al.68 | 2018 | 40 | – | – | – | – |

| Lowe et al.46 | 2018 | 30 | – | – | – | – |

| Merolla et al.76 | 2018 | 74 | 142° | 131° | 31° | – |

| Padegimas et al.b,22 | 2016 | 393 | – | – | – | – |

| Padegimas et al.69 | 2018 | 14 | 110° | – | – | – |

| Parisien et al.57 | 2016 | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| Raiss et al.70 | 2018 | 77 | – | – | – | – |

| Sanchez-Sotelo et al.50 | 2018 | 90 | 131° | – | 46° | L4 |

| Schnetzke et al.24 | 2017 | 24 | 119° | 127° | 23° | – |

| Thomasson et al.23 | 2015 | 57 | – | – | – | – |

| Torrens et al.71 | 2016 | 81 | 124° | – | – | – |

| Updegrove et al.72 | 2018 | 37 | – | – | – | – |

| Verdano et al.73 | 2018 | 32 | 120° | 120° | 14° | S1 |

| Yoon et al.74 | 2017 | 35 | 133° | – | 37° | L1 |

| Zilber et al.75 | 2018 | 35 | – | – | – | – |

| Weighted mean | 122.4° ± 11.5° | 109° ± 19.4° | 33° ± 11.2° | 41° ± 5° | ||

ER: external rotation; IR: internal rotation.

aNo range of motion reported.

Table 4.

Complications of rTSA.a

| Authors | Year | Scapular notching | Radiolucent lines around glenoid | Heterotopic ossification | Dislocation | Infection | Humeral stem loosening | Acromion fracture | Neuropraxia | Cubital tunnel syndrome | Humeral fracture | Miscellaneous | # of Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chalmers et al.64 | 2014 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | – | – | – | 1 (II) | – | – | – | 9 |

| Formaini et al.48 | 2015 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (III) required revision to long stem prosthesis | – | 25 |

| Frank et al.65 | 2018 | – | – | – | 5 (III) | 2 (II) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 243 |

| Uzer et al.47 | 2017 | 1 (I) | – | – | – | 2 (II) | 1 (III); treated with humeral component revision | – | – | – | 1 (III) fixation with limited-contact dynamic compression plate | – | 33 |

| Izquierdo-Fernández et al.66 | 2017 | 14 (I) | 16 (I) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 29 |

| Jonušas et al.67 | 2017 | 0 | – | 2 (I) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (I(tubercle malposition) | 27 |

| Jorge-Mora et al.49 | 2018 | – | – | – | 1 (III); treated with component exchange | 1 (III); treated with debridement and mobile component exchange | – | – | – | – | 1 (II); treateted locking stem and cerclage | – | 58 |

| Kirzner et al.68 | 2018 | 21 (1) | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | 2 scapular spine fracture; treated non-operatively | 40 |

| Lowe et al.46 | 2018 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 (II); not surgically treated | 1 (II) | – | – | 1 (I) perforated stomach ulcer | 30 |

| Merolla et al.76 | 2018 | 16 (1) | 5 (1) | 14 (1) | 4 (III); 3 treated with closed reduction, 1 required higher PE implant | 3 (II/III); 1 (III) required one-step implant exchange | 13 (III) | 1 (III); treated with ORIF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (II) scapular spine fracture; treated non-operatively | 74 |

| Padegimas et al.b,22 | 2016 | – | – | – | 5 (III); treated with polyethylene component exchange | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 393 |

| Padegimas et al.69 | 2018 | – | – | – | 2 (III); 1 treated with component exchange, 1 treated with polyethylene exchange | 0 | – | 1 (II); not surgically treated | – | – | – | – | 14 |

| Parisien et al.57 | 2016 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (II) | – | – | 12 | |

| Raiss et al.70 | 2018 | 1(III); treated with polyethylene exchange | 2 (III); treated with debridement, polyethylene and glenoid exchange | 1 (II); treated non-operatively | 77 | ||||||||

| Sanchez-Sotelo et al.50 | 2018 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 2 (III); treated two-stage revision | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (III); treated with cemented humeral component revision and fracture fixation | 1 glenoid component loosening treated with HA (III); 1 scapular stress fracture (II) | 90 |

| Schnetzke et al.24 | 2017 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 2 (II) | – | – | – | 8 (cortical thinning/osteopenia) (I) | 24 |

| Thomasson et al.23 | 2015 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6 (II) | 1 (III) | – | – | 57 |

| Torrens et al.71 | 2016 | 26 (I) | – | – | 2 (III); required revision | 0 | – | 1 (II); not surgically treated | – | – | – | 81 | |

| Updegrove et al.72 | 2018 | 3 | 0 | 5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 |

| Verdano et al.73 | 2018 | 3 | – | 3 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 32 |

| Yoon et al.74 | 2017 | 20 (I) | – | – | 0 | 0 | – | 1(II) | – | – | – | 1 AC separation (I) | 35 |

| Zilber et al.75 | 2018 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 perioperative glenoid fracture; no treatment (I) | 35 |

| Total complications | 115 | 26 | 39 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 18 | 206 | |

| Total patients | 512 | 273 | 270 | 1141 | 796 | 256 | 532 | 330 | 256 | 257 | 355 | 1455 | |

| % of patients | 22.5 | 9.5 | 14.4 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 5.5 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 5.1 | 18.28 | |

aData reported as count (complication grade).

Patient outcomes

Clinical measures of post-operative shoulder ROM were reported in seven studies (234 patients; Table 3). Mean forward flexion of the shoulder was 122.4° ± 11.5°; mean shoulder abduction was 109° ± 19.4°; mean external rotation was 33° ± 11.2°; mean internal rotation was 41° ± 5°. Nine studies did not report any measures of shoulder movement (710 patients).

Post-operative outcomes of Constant, ASES, SST, and VAS pain scores were abstracted from 16 of the included studies (858 patients; Table 5). The mean Constant score was 58.9 ± 10.1; mean ASES score was 73.4 ± 6.1, mean SST score was 63.5 ± 6.5, and mean VAS pain was 1.6 ± 0.9. Six studies did not report any clinical outcomes (583 patients; Table 5). Due to inconsistent pre-operative/baseline score reporting, it was not possible to report mean changes in score from pre-operative to post-operative across the various indications. Additionally, return to activity rates and arthroplasty survivorship was not reported in the included studies.

Table 5.

Clinical outcomes after rTSA.

| Authors | Year | Total Cases | Constant | ASES | SST | VAS Pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chalmers et al.64 | 2014 | 9 | – | 80 | 58.3 | 1 |

| Formaini et al.48 | 2015 | 25 | – | 71 | 58.3 | 2 |

| Frank et al.65 | 2018 | 243 | – | 78.6 | 66.7 | 1.1 |

| Uzer et al.47 | 2017 | 33 | 39.7 | 61.1 | – | – |

| Izquierdo-Fernández et al.66 | 2017 | 29 | – | 72.0 | – | – |

| Jonušas et al.67 | 2017 | 27 | 57.6 | – | 73.5 | – |

| Jorge-Mora et al.49 | 2018 | 58 | 57.1 | – | – | – |

| Kirzner et al.68 | 2018 | 40 | – | 70.0 | – | – |

| Lowe et al.46 | 2018 | 30 | – | – | – | – |

| Merolla et al.76 | 2018 | 74 | 70.4 | – | – | 0.9 |

| Padegimas et al.b,22 | 2016 | 393 | – | – | – | – |

| Padegimas et al.69 | 2018 | 14 | – | – | – | – |

| Parisien et al.57 | 2016 | 12 | – | – | – | – |

| Raiss et al.70 | 2018 | 77 | – | – | – | – |

| Sanchez-Sotelo et al.50 | 2018 | 90 | – | 77.2 | – | – |

| Schnetzke et al.24 | 2017 | 24 | 57.1 | – | – | – |

| Thomasson et al.23 | 2015 | 57 | – | – | – | – |

| Torrens et al.71 | 2016 | 81 | 55.8 | – | – | – |

| Updegrove et al.72 | 2018 | 23 | – | 79.6 | – | – |

| Verdano et al.73 | 2018 | 32 | 64 | – | – | – |

| Yoon et al.74 | 2017 | 35 | 74.8 | 71.8 | 60.8 | 3 |

| Zilber et al.75 | 2018 | 35 | 54 | – | – | – |

| Weighted mean ± SD | 58.9 ± 10.1 | 73.5 ± 6.1 | 63.5 ± 6.5 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | ||

ASES: American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Shoulder Score; SST: Simple Shoulder Test; VAS: visual analog scale.

aNo PROs reported.

Discussion

The key findings of this study were that the major and minor complication rate of primary rTSA was lower after 2010 compared to before 2010. More specifically, the overall complication rate of 18.2% is lower than previous reported rates of 19%–68%,16,17 with the rate of “major” complications compared dropping approximately three-fold from 15.4% to 4.6%. The reduction in the overall complication rate of primary rTSA is largely due to the significant reduction of major post-operative complications, such as dislocations and infections. Since both grade II and grade III “major” complications require additional management, the reduction of these complications directly affects the postoperative management of patients. Presumably, it appears that with improvements in surgical technique, prosthesis design, surgeon familiarity, and patient selection, rTSA remains a viable surgical option in the primary setting with wide applicability and a relatively low complication profile.

Clinical outcomes

Considering that primary rTSA was introduced as an alternative to HA and aTSA to improve post-operative range of motion and pain in patients, these clinical outcomes reported are crucial to the evaluation of rTSA in the primary setting post-2010. Compared to previous (pre-2010) values, improvements in all mean dimensions of range of motion were found.25 Given that post-operative forward elevation and abduction greater than 100° and internal and external rotation greater than 40° has been previously suggested to be satisfactory for most day-to-day activities,26 these goals have been better achieved post-2010. The reported Constant score, ASES, SST, and VAS pain scores indicate post-operative success in regaining day-to-day shoulder function.

“Major” complications

The dislocation rate of 1.3% decreased from pre-2010 rates, which ranged from 4.7%to 6.2%.27,28 Non-surgical management of dislocations is possible, but the reported success rate of closed reduction ranges from 44% to 62%.29 Post-operative dislocations that cannot be reduced in a closed setting are serious complications that require revision. All of the patients with dislocations in this review (fifteen patients) were managed with surgical revision. It was not reported if closed reduction was attempted prior to surgical intervention in these studies. Although the cause of dislocation from primary rTSA may be multifactorial, the most commonly cited is intraoperative; stemming from inadequate tensioning of the deltoid and conjoint tendon,3,30–32 poor implant positioning leading to impingement,33,34 subscapularis incompetency,35 the delto-pectoral surgical approach,3,30,36–40 and/or a combination of any of these factors. These risks for dislocation have been frequently reported in the literature prior to 2010, and it remains plausible that a heightened awareness of these risk factors has led to the decreased dislocation rates observed.

While infection remains a serious complication for rTSA, the rates of deep infection (1.6%) decreased from the previously reported range of 3.8%27 to 6.5%.41 It is possible that the reduction in infection-related complications in rTSA is representative of those lessons learned from hip and knee arthroplasty: decreased operative time, improved patient selection, and increased adherence to antiseptic approaches (i.e. antibiotic cement, changing gloves prior to final component handling and implantation, etc.).42–44

The remainder of the “major” complications including neuropraxia, humeral fracture, humeral stem loosening, and acromion fracture have remained unchanged relative to pre-2010 rates. The observed neuropraxias included CuTS, carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), distal radial sensory neuropathy, and ulnar sensory neuropathy. Common nerve injuries incurred during shoulder surgery, in decreasing frequency, are traction injuries to the brachial plexus (46.7%), musculocutaneous (20%), axillary (16.7%), ulnar (10%), and radial nerves (6.7%).45 Considering that neuropraxia is not as frequently reported as more severe neurological complications that require surgical management, it is important to discuss both neuropraxia and nerve damage requiring surgery together. In this review, the reported rate of nerve damage requiring surgical intervention is 0.4% (one case of surgical decompression of the cubital nerve). Prior to 2010, the overall rate of consequential nerve damage ranged from 1.2%27 to 3.4%.41 While it is difficult to discern if the rate of neurological complications has changed significantly since 2010, these results demonstrate promise that the increased clinical familiarity and implant design of rTSA might factor into the reduced overall rate of postoperative neuropraxia.46

The combined humeral stem loosening and humeral fracture complication rate (7%) did not increase substantially from values reported prior to 2010.27 The four reported humeral fractures were both periprosthetic humeral fractures at the distal tip of the humeral stem,47–50 requiring long-stem revision,48 fixation with a 4.5 mm limited-contact dynamic compression plate and humeral component revision,47 fixation with locking stem and cerclage,49 and treatment with humeral component revision and unspecified fixation.50 Other reviews have combined both humeral fracture and stem loosening into a combined humeral complication rate of 5.6%.41 Neither the individual rate of humeral fracture nor stem loosening has changed dramatically since prior to 2010.

The rate of acromion fracture (2.3%) did not differ from the rate of acromion fracture prior to 2010, but that rate nonetheless remains a complication of concern.27,41 Risk factors for acromion fracture in rTSA include: the increased mechanical load on the acromion by medialization of the humeral center of rotation38; the deltopectoral surgical approach38; and extra tension on the deltoid from prosthetic induced humeral lengthening. While the patients included in this review did not require surgical management of their acromion fractures, there is no consensus on the optimal surgical technique or treatment approach for this complication.51

“Minor” complications

While “minor” complications such as peri-glenoid radiolucency, scapular notching, and HO do not necessitate invasive management strategies, they remain a prominent issue for primary rTSA. Peri-glenoid radiolucency and HO appear to have increased in frequency, while scapular notching appears to have decreased in frequency post-2010.

Although scapular notching has decreased from 35.4%27–47.1%41 to 22.5% post-2010, it remains one of the most frequent and highly controversial complications of primary rTSA. Although some strongly support the hypothesis that scapular notching predisposes to glenoid component loosening and/or poor clinical outcomes,40,52–55 the most comprehensive study on the topic has not conclusively demonstrated this.56 It is unclear whether this observed decrease relative to the pre-2010 rates is attributable to presumed modifications in prosthesis design and surgical experience, or if it reflects an underestimate due to selection biases and short follow-up times.22,23,57 Interestingly, however, none of the patients herein with reported scapular notching required additional management.

The rate of peri-glenoid radiolucency (9.5%) has increased relative the pre-2010 rates of 2.9%.27 Interestingly, no correlation between the presence of post-operative peri-glenoid radiolucency and rTSA failure or revision has been reported.27 Thus, this apparent increase may be attributable to selection and/or time lag biases, more so than a true clinically significant sequela. The rate of radiographic HO (14.4%) has increased from pre-2010 levels (0.8%).27 While HO usually impinges postoperative mobility, the mean range of motion in multiple planes was unaffected in the included patient. Despite the observed rise in HO, this finding is likely insignificant in determining postoperative outcome.

The widely accepted total complication rates for aTSA and HA at 10% and 7%, respectively, are still less than the 18.2% total complication rate reported herein.14,30,58,59 It has not escaped notice, however, that the rates in aTSA and HA may be underestimates, as they only reflect “major” complications requiring post-operative management. Thus, it is possible that the true and most comparable complication rate of rTSA, reported at 4.6% herein, is possibly equivalent to, if not lower than reported values for other arthroplasty options. While a direct comparison of complications is complicated by an inconsistent reporting schema across studies, the clinical benefits regarding ROM and post-operative shoulder function of rTSA are comparable to aTSA and HA, as is the survivability – particularly in patients with poor bone quality,60,61 rotator cuff deficiency, and advanced age.62 In addition, the survival rate of rTSA implants at 91% over 10 years remains comparable to the survival rate of aTSA and HA. Within this review, the two most frequent indications for rTSA were rotator cuff tear arthropathy and proximal humeral fracture. For patients presenting with rotator cuff tear arthropathy, rTSA is still the preferred technique, as the lateralization of the prosthesis properly tensions the deltoid to compensate for cuff deficiency.12 However, how this compares to other non-arthroplasty techniques such as tendon transfer and/or superior capsular reconstruction warrants further attention. In contrast, the management of proximal humeral fracture with arthroplasty is still a surgeon-dependent choice. Either open reduction internal fixation or HA was the preferred choice of reconstruction for displaced proximal humeral fractures until the advent of rTSA. Recent evidence including a large, randomized clinical study has demonstrated that rTSA, compared to HA, provides superior clinical and radiographic outcomes in patients with proximal humeral fractures.63 rTSA remains a preferable option to TSA and HA for patients presenting with rotator cuff tear arthropathy12 or proximal humeral fractures.63 However, how non-arthroplasty options compare such as tendon transfer and/or superior capsular reconstruction for CTA or open reduction internal fixation for fractures warrants further attention.

This review is limited by several factors. Inclusion of studies with patient populations recruited after 2010 with any degree of follow-up may underestimate complication rates as well as fail to report post-operative survivorship. The overall quality of the data published regarding rTSA, as reflective of the average “moderate” MINORS score, single center/surgeon studies and lack of registry data, limits interpretation of the results included within this review. The included studies employed differing surgical implants and indications as well as reported inconsistent outcomes and complications indices. An additional limitation of the study design is that pre-2010 outcome data are abstracted from previously published reviews rather than primary text as the exclusion criteria necessitated removal of these manuscripts from final abstraction. These limitations highlight the need for additional clinical studies, correlated with large clinical outcomes registry data to ascertain a more comprehensive understanding of the rate of complications, clinical outcomes, and indications of rTSA in the primary setting.

An inherent strength of this review is that it captures a continuing concern regarding persistently high levels of “minor” complications with rTSA in the primary setting. Despite the limited clinical and biomechanical research suggesting negligible consequences from these complications, it is still a challenge to contemporary clinical practice to determine the relevance of these “minor” complications to surgical decision making.

Conclusions

Since 2010, there has been a marked decrease in “major” complications that require non-surgical management and/or surgical revision. In fact, the data presented herein suggest that rTSA is a safe and efficacious alternative to aTSA and HA across a wide range of pathology in the primary setting and should not be viewed as a salvage option. This, and the relatively “stale” nature of previous complication profiles are points fundamental to the perioperative discussions surrounding this procedure in the primary setting.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: Raphael Crum, Darren de SA, and Favian Su assisted with study design, data abstraction and analysis, and manuscript preparation. Bryson Lesniak and Albert Lin assisted with study design and manuscript preparation and review.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32GM008208. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Ethical review and patient consent

No ethical review and patient consent were necessary for this study.

References

- 1.Flatow EL, Harrison AK. A history of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469: 2432–2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berliner JL, Regalado-Magdos A, Ma CB, et al. Biomechanics of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, et al. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14(1 Suppl S): 147S–161S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker M, Brooks J, Willis M, et al. How reverse shoulder arthroplasty works. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469: 2440–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jazayeri R, Kwon YW. Evolution of the reverse total shoulder prosthesis. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2011; 69: 50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grammont PM, Baulot E. Delta shoulder prosthesis for rotator cuff rupture. Orthopedics 1993; 16: 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grammont P, Trouilloud P, Laffay JP, et al. Concept study and realization of a new total shoulder prosthesis. Rhumatologie 1997; 39: 407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schairer WW, Nwachukwu BU, Lyman S, et al. National utilization of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, et al. The Reverse Shoulder Prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 1697–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werner CML, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, et al. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 1476–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95: 2050–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drake GN, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB. Indications for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in rotator cuff disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 1526–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis in patients with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; Jul; 95: 1297–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groh GI, Groh GM. Complications rates, reoperation rates, and the learning curve in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kempton LB, Ankerson E, Wiater JM. A complication-based learning curve from 200 reverse shoulder arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469: 2496–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rittmeister M, Kerschbaumer F. Grammont reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and nonreconstructible rotator cuff lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2001; 10: 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O’Connor DP, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89: 1476–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, et al.; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist – finding what works in health care – NCBI Bookshelf, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24983062 (2011). [PubMed]

- 19.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 2003; 73: 712–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sink EL, Leunig M, Zaltz I, et al. Academic Network for Conservational Hip Outcomes Research Group. Reliability of a complication classification system for orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470: 2220–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012; 22: 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padegimas EM, Zmistowski BM, Restrepo C, et al. Instability after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: which patients dislocate? Am J Orthop 2016; 45: E444–E450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomasson BG, Matzon JL, Pepe M, et al. Distal peripheral neuropathy after open and arthroscopic shoulder surgery: an under-recognized complication. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnetzke M, Preis A, Coda S, et al. Anatomical and reverse shoulder replacement with a convertible, uncemented short-stem shoulder prosthesis: first clinical and radiological results. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2017; 137: 679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy J-S, Macdermid JC, Goel D, et al. What is a successful outcome following reverse total shoulder arthroplasty? Open Orthop J 2010; 4: 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doorenbosch CAM, Harlaar J, Veeger DHEJ. The globe system: an unambiguous description of shoulder positions in daily life movements. J Rehabil Res Dev 2003; 40: 147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zumstein MA, Pinedo M, Old J, et al. Problems, complications, reoperations, and revisions in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 146–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farshad M, Gerber C. Comment on Table 1 of Farshad and Gerber: reverse total shoulder arthroplasty – from the most to the least common complication. Int Orthop 2011; 35: 455–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalmers PN, Rahman Z, Romeo AA, et al. Early dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Affonso J, Nicholson GP, Frankle MA, et al. Complications of the reverse prosthesis: prevention and treatment. Instr Course Lect 2012; 61: 157–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallo RA, Gamradt SC, Mattern CJ, et al. Instability after reverse total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gutiérrez S, Keller TS, Levy JC, et al. Hierarchy of stability factors in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466: 670–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephenson DR, Oh JH, McGarry MH, et al. Effect of humeral component version on impingement in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 652–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. The reverse shoulder prosthesis in the treatment of fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92: 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edwards TB, Williams MD, Labriola JE, et al. Subscapularis insufficiency and the risk of shoulder dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18: 892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.deWilde LF, Van Ovost E, Uyttendaele D, et al. Results of an inverted shoulder prosthesis after resection for tumor of the proximal humerus. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2002; 88: 373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerber C, Pennington SD, Nyffeler RW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009; 17: 284–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molé D, Favard L. Excentered scapulohumeral osteoarthritis. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2007; 93(6 Suppl): 37–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seebauer L. Total reverse shoulder arthroplasty: European lessons and future trends. Am J Orthop 2007; 36(12 Suppl 1): 22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, et al. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86: 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farshad M, Gerber C. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty-from the most to the least common complication. Int Orthop 2010; 34: 1075–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricciardi BF, Bostrom MP, Lidgren L, et al. Prevention of surgical site infection in total joint arthroplasty: an international tertiary care center survey. HSS J 2014; 10: 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solarino G, Abate A, Vicenti G, et al. Reducing periprosthetic joint infection: what really counts? Joints 2015; 3: 208–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson R, Jameson SS, Sanders RD, et al. Reducing surgical site infection in arthroplasty of the lower limb: a multi-disciplinary approach. Bone Joint Res 2013; 2: 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagda SH, Rogers KJ, Sestokas AK, et al. Neer Award 2005: Peripheral nerve function during shoulder arthroplasty using intraoperative nerve monitoring. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16(3 Suppl): S2–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lowe JT, Lawler SM, Testa EJ, et al. Lateralization of the glenosphere in reverse shoulder arthroplasty decreases arm lengthening and demonstrates comparable risk of nerve injury compared with anatomic arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018; 27: 1845–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uzer G, Yildiz F, Batar S, et al. Does grafting of the tuberosities improve the functional outcomes of proximal humeral fractures treated with reverse shoulder arthroplasty? J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2017; 26: 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Formaini NT, Everding NG, Levy JC, et al. Tuberosity healing after reverse shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humerus fractures: the “black and tan” technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: e299–e306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jorge-Mora A, Amhaz-Escanlar S, Fernández-Pose S, et al. Early outcomes of locked noncemented stems for the management of proximal humeral fractures: a comparative study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2019; 28: 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanchez-Sotelo J, Nguyen NTV and Morrey ME. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty using a bone-preserving glenoid component: clinical and radiographic outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Arthroplast 2018; 2:247154921876168.

- 51.Walch G, Mottier F, Wall B, et al. Acromial insufficiency in reverse shoulder arthroplasties. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18: 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boileau P, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty combined with a modified latissimus dorsi and teres major tendon transfer for shoulder pseudoparalysis associated with dropping arm. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466: 584–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boulahia A, Edwards TB, Walch G, et al. Early results of a reverse design prosthesis in the treatment of arthritis of the shoulder in elderly patients with a large rotator cuff tear. Orthopedics 2002; 25: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.deWilde L, Mombert M, Van Petegem P, et al. Revision of shoulder replacement with a reversed shoulder prosthesis (Delta III): report of five cases. Acta Orthop Belg 2001; 67: 348–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valenti P, Boutens D, Nerot C. Delta 3 reversed prosthesis for arthritis with massive rotator cuff tear: long term results (>5 years). In: Walch G, Boileau P and Mole P (eds) 2000 Shoulder Prosthesis: two to ten years follow up. Montpellier: Sauramps Medical, 2001, pp. 253–259.

- 56.Lévigne C, Boileau P, Favard L, et al. Scapular notching in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 925–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parisien RL, Yi PH, Hou L, et al. The risk of nerve injury during anatomical and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: an intraoperative neuromonitoring study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016; 25: 1122–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheung E, Willis M, Walker M, et al. Complications in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011; 19: 439–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wierks C, Skolasky RL, Ji JH, et al. Reverse total shoulder replacement: intraoperative and early postoperative complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bufquin T, Hersan A, Hubert L, et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: a prospective review of 43 cases with a short-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89: 516–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klein M, Juschka M, Hinkenjann B, et al. Treatment of comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus in elderly patients with the Delta III reverse shoulder prosthesis. J Orthop Trauma 2008; 22: 698–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lenarz C, Shishani Y, McCrum C, et al. Is reverse shoulder arthroplasty appropriate for the treatment of fractures in the older patient? Early observations. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469: 3324–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sebastiá-Forcada E, Cebrián-Gómez R, Lizaur-Utrilla A, et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fractures. A blinded, randomized, controlled, prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 1419–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chalmers PN, Slikker W, Mall NA, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for acute proximal humeral fracture: comparison to open reduction-internal fixation and hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frank RM, Lee S, Sumner S, et al. Shoulder arthroplasty outcomes after prior non-arthroplasty shoulder surgery. JB JS Open Access 2018; 3: e0055–e0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Izquierdo-Fernández A, Minarro JC, Carpintero-Lluch R, et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in obese patients: analysis of functionality in the medium-term. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018; 138: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jonušas J, Banytė R, Ryliškis S. Clinical and radiological outcomes after reverse shoulder arthroplasty with less medialized endoprosthesis after mean follow-up time of 45 months. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2017; 137: 1201–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kirzner N, Paul E, Moaveni A. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty vs BIO-RSA: clinical and radiographic outcomes at short term follow-up. J Orthop Surg Res 2018; 13: 256–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Padegimas EM, Nicholson TA, Silva S, et al. Outcomes of shoulder arthroplasty performed for postinfectious arthritis. Clin Orthop Surg 2018; 10: 344–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raiss P, Alami G, Bruckner T, Magosch P, et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for type 1 sequelae of a fracture of the proximal humerus. Bone Joint J 2018; 100–B: 318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Torrens C, Guirro P, Miquel J, et al. Influence of glenosphere size on the development of scapular notching: a prospective randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016; 25: 1735–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Updegrove GF, Nicholson TA, Namdari S, et al. Short-term results of the DePuy Global Unite Platform Shoulder System: a two-year outcome study. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2018; 6: 353–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Verdano MA, Aliani D, Galavotti C, et al. Grammont versus lateralizing reverse shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humerus fracture: functional and radiographic outcomes. Musculoskelet Surg 2018; 102(Suppl 1): 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoon JP, Seo A, Kim JJ, et al. Deltoid muscle volume affects clinical outcome of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with cuff tear arthropathy or irreparable cuff tears. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0174361–e0174361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zilber S, Camana E, Lapner P, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty using helical blade to optimize glenoid fixation and bone preservation: preliminary results in thirty five patients with minimum two year follow-up. Int Orthop 2018; 42: 2159–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Merolla G, Walch G, Ascione F, et al. Grammont humeral design versus onlay curved-stem reverse shoulder arthroplasty: comparison of clinical and radiographic outcomes with minimum 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018; 27: 701–710. [DOI] [PubMed]