Abstract

Background

Limited evidence exists which details changes in quality of life, shoulder activity level, kinesiophobia, shoulder pain and disability following a first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation (FTASD) in people treated non-operatively. This study had three objectives: (1) to examine quality of life, pain, disability and kinesiophobia after an FTASD within 12 weeks, (2) to examine whether these variables were different in people with and without recurrent shoulder instability and (3) to assess how these variables changed over 12 months.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was undertaken in people with an FTASD aged between 16 and 40 years. Measures of quality of life, kinesiophobia, shoulder activity, shoulder pain and disability were recorded within 12 weeks of an FTASD and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months.

Results

An FTASD negatively impacted quality of life, shoulder pain and function and these variables improved over time. People with recurrent shoulder instability had poorer quality of life 12 months after an FTASD. Across the entire cohort, kinesiophobia did not significantly change across time in people following an FTASD.

Conclusions

Quality of life was significantly affected by an FTASD in people with recurrent shoulder instability. Across the entire cohort of people with an FTASD, kinesiophobia remained elevated in people following an FTASD.

Level of evidence

Level 1 prognostic study.

Keywords: shoulder, dislocation, fear, quality of life

Introduction

Background

Rates of recurrent shoulder instability after a first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation (FTASD) range from 26% to 100%, with heterogeneity of these results primarily dependent upon study methods, age and pathological lesions.1,2 People who have an FTASD are interested in how long their shoulder will be painful for and how it will affect their level of function and quality of life. While recurrent shoulder instability is a much-studied topic,3–5 there is limited literature available regarding the impact of recurrent shoulder instability on quality of life, shoulder pain and disability, shoulder activity levels and kinesiophobia. Patients’ self-reported shoulder function was examined in a large prospective study in Sweden and found to be similar in people with recurrent shoulder instability who did not receive surgical intervention and became ‘stable over time’ when compared to those with a single dislocation and those that were treated surgically.6 Shoulder pain following an FTASD has been examined in a prospective cohort study and pain greater than 8/10 on the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) was a statistically significant multivariate predictor for subsequent recurrent shoulder instability.7 However, the time for resolution of shoulder pain and function after an FTASD is currently unknown.

Some authors have shown decreased quality of life two years after a shoulder instability event.8 Others have shown decreased quality of life in people who have recurrent shoulder instability when compared to people who do not have recurrent shoulder instability or stabilisation surgery,7,9 while some have shown no difference.10 Thus, further examination of the time course, and the effect of recurrent shoulder instability on quality of life is required. Furthermore, while fear of reinjury after shoulder instability has been reported in the literature,11,12 there is limited evidence regarding the degree of kinesiophobia (defined as fear of movement and reinjury13) immediately post-injury or over time after an FTASD.14

There is a plethora of research that has examined the effects of recurrent shoulder instability following shoulder dislocation, but the systematic reviews that examine recurrent shoulder instability3–5,15 have not examined reported time frames for recovery after an FTASD, such as how long their shoulder will be painful for, how long their function will be affected and what the impact will be on their quality of life. Additionally, while kinesiophobia has been reported in the literature after a shoulder instability event,14 the trajectory of kinesiophobia following an FTASD is currently unknown. As part of a large national cohort study of risk factors for recurrent shoulder instability, we aimed to also examine the impact of a shoulder dislocation of pain, function, quality of life and kinesiophobia, and the trajectory of these variables over the subsequent 12 months.

There were three main objectives of this part of the study:

to examine the level of quality of life, pain and disability, and kinesiophobia within 12 weeks following an FTASD;

to examine whether these variables were different in people with and without recurrent shoulder instability managed non-operatively over the 12 months post-injury;

to assess how these outcome variables changed over the following 12 months for the entire non-operative cohort who had an FTASD.

Methods

A national prospective cohort study was undertaken in New Zealand with people who had sustained an FTASD between August 2015 and March 2017. In New Zealand, people who have a traumatic accident present to health professionals who record their details using a specified coding system (including injury details) with the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC), a government-owned corporation responsible for administering the country’s universal no-fault accidental injury scheme. The ACC database was reviewed by an ACC employed administrator who was independent to the study, to identify people with injury codes relevant to a shoulder dislocation. The administrator sent a letter of invitation to all those with an injury code denoting shoulder instability who had not received surgery for their injury. Those who did not opt-out were contacted by telephone by the first author, who explained the study, checked for eligibility, and if in agreement, took informed consent.

People were included in the study if they were aged between 16 and 40 years (as rates of recurrent instability decrease after 40 years of age), sustained an FTASD in New Zealand between May 2015 and April 2016 which was registered with ACC, had a shoulder X-ray following their FTASD, had a New Zealand contact address and had not undergone surgical intervention for their shoulder injury within 12 weeks of the injury. The initial X-ray and any other radiological imaging were reviewed to confirm the anterior shoulder dislocation. People were excluded if they had a previous shoulder instability episode or if they did not speak conversational English (as they were unable to participate in the telephone interview). People were also excluded if radiological records showed an injury of the isolated acromio-clavicular joint injury without an anterior dislocation, a posterior or inferior dislocation or a previous instability event. People with a Bony Bankart lesion or greater tuberosity fracture were included in the study.

Consenting participants were followed for 12 months after their FTASD. Quality of life, level of shoulder activity, shoulder pain and function, and kinesiophobia were assessed over the phone via the following outcome measures, respectively: Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI), Shoulder Activity Scale (SAS), Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), NPRS and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-11). Baseline shoulder activity was reported as the level prior to the FTASD, to enable investigation of the length of time taken to regain previous shoulder activity after an FTASD. Baseline measures for the remaining variables were measured at the initial interview, subsequent to the FTASD to assess the immediate impact of an FTASD. Phone calls were made to participants within 12 weeks of their FTASD and at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post-injury.

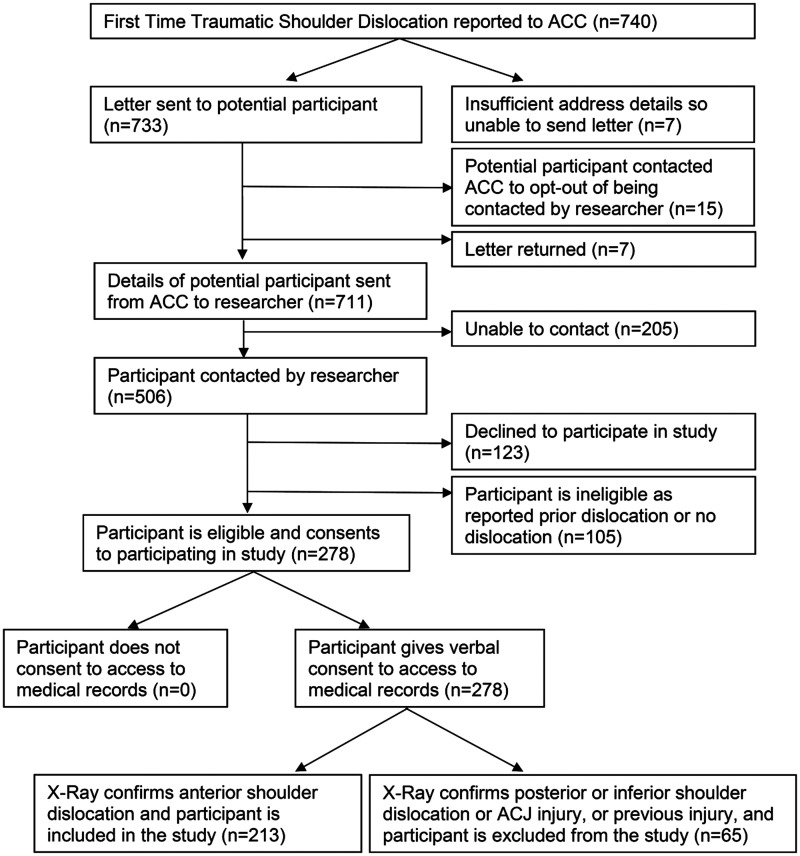

A summary of recruitment figures can be seen in Figure 1. Of the 711 people referred to the study, 205 were not contactable (29%). Of the remaining 506, 24% declined to participate, 34% were ineligible and 42% were eligible and provided consent (n = 213).

Figure 1.

Flow of people through the study.

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees of the Auckland University of Technology (approval number 14/256) and the ACC (approval number 272). This study was part of a larger study which examined predictive variables for recurrent shoulder instability after an FTASD. Linear mixed-effects models were undertaken to assess the difference between the outcomes of interest at the relevant follow-up time points compared with baseline values. A p-value ≤ 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Post-hoc power analysis (with alpha set at 0.05 (two-sided), power = 80% to see a difference between people with recurrent instability compared to those without recurrent shoulder instability within 12 months follow-up) revealed that the study was powered at 91% for quality of life (WOSI total) and 66% for both kinesiophobia (TSK-11) and shoulder pain (SPADI-Pain). Post-hoc power analysis over time for the entire cohort revealed that the study was powered at 85% for all variables.

Results

Baseline data were collected from 213 participants, with data concerning recurrent instability status at 12 months available for 186 participants (87%). Data were collected within 12 weeks of a dislocation (mean number of days from dislocation to data collection was 66.75 (21.53) days, range = 22–120 days). Not all those who remained in the study and provided recurrence data wished to complete the outcome measures. Therefore, follow-up data were available for 76 (36%) at 3 months, 76 (36%) at 6 months, 65 (31%) at 9 months and 86 (40%) at 12 months. The mean age was 25 years and 15% were female. People who were aged 16–25 years had increased rates of recurrent instability (p = 0.02) compared with people aged 26–40 years. There was no difference in baseline kinesiophobia (p = 0.06) or quality of life (p = 0.42) between these age groups. Of the 213 people who were recorded at baseline, 164 (77%) had received physiotherapy for an average of seven sessions.

In regard to the specific study objectives:

To examine the level of quality of life, pain and disability, and kinesiophobia after an FTASD within 12 weeks: Within 12 weeks of an FTASD, people had low levels of quality of life, indicated by a mean WOSI total score of 844.2 of a possible 2100 (Table 1). A WOSI score of 0 indicates no impact on quality of life, whereas a score of 2100 indicates an extreme impact on quality of life.16 Within 12 weeks of an FTASD, people had some pain and disability with a mean SPADI score of 20.82, where a score of 0 indicates no pain or disability and 100 represents the maximum level of impairment (Table 1).17 Likewise, people experienced some kinesiophobia with mean TSK-11 values of 25.92 within 12 weeks of an FTASD, where 11 represents the minimum level of kinesiophobia and 44 the maximum level.18 People were asked in their initial interview to recall the amount of pain they experienced at the time of dislocation. They recalled that the pain experienced at the time of the FTASD was an average NPRS of 7.99 out of 10. At the time of the initial interview, this had decreased to an average NPRS of 1.68.

To examine whether these variables were different in people with and without recurrent shoulder instability over the following 12 months: The rate of reported recurrent shoulder instability (10.3% at 3 months, 19.3% at 6 months, 22.1% at 9 months and 30.5% at 12 months) can be seen in Figure 2. Differences in outcome scores of quality of life, shoulder pain and disability, kinesiophobia and shoulder activity between people with and without recurrent shoulder instability are shown in Table 2. People who had recurrent shoulder instability had significantly more shoulder pain (SPADI Pain) compared to people without recurrent shoulder instability (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient-reported outcome measures within 12 weeks of a first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation.

| Variable name | N | Overall mean (s.d.) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPADI pain | 213 | 25.17 (20.91) | 0–96 |

| SPADI function | 213 | 18.80 (19.6) | 0–93 |

| SPADI total | 213 | 20.82 (19.39) | 0–92 |

| TSK-11 total | 213 | 25.92 (4.38) | 11–37 |

| WOSI (physical) | 213 | 362.30 (215.30) | 0–880 |

| WOSI (recreation) | 213 | 182.40 (110.20) | 0–400 |

| WOSI (life) | 213 | 144.80 (104.60) | 0–380 |

| WOSI (emotion) | 213 | 154.60 (83.60) | 0–300 |

| WOSI total | 213 | 844.20 (471.2) | 0–1820 |

SPADI: Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (range 0–100, higher scores denote worse pain and function), TSK-11: Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia 11 (range 11–44, higher scores denote worse kinesiophobia), WOSI: Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (range 0–2100, higher scores denote worse quality of life).

Figure 2.

Percentage of recurrent and non-recurrent shoulder instability over 12 months after an FTASD. *Those who were non-contactable at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months were coded as missing.

Table 2.

Change in patient-reported outcome measures for the entire cohort over the 12 months after an FTASD compared to baseline (or pre-injury) values.

| Beta coefficient | SE | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder activity level (SAS) | Pre-injury | 12.26 | 0.35 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | −1.62 | 0.48 | 0.001* |

| 6 months | −1.12 | 0.48 | 0.019* | |

| 9 months | −0.99 | 0.52 | 0.059 | |

| 12 months | −0.88 | 0.48 | 0.070 | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | −0.03 | 0.56 | 0.961 |

| Missing at 12 months vs. no | <−0.01 | 0.79 | 0.998 | |

| Shoulder pain (SPADI pain) | Baseline | 21.36 | 1.68 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | −4.38 | 1.99 | 0.028* |

| 6 months | −9.27 | 1.95 | <0.001* | |

| 9 months | −9.78 | 2.09 | <0.001* | |

| 12 months | −11.92 | 1.98 | <0.001* | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 7.66 | 2.19 | 0.001* |

| Missing at 12 months vs. no | 10.07 | 3.63 | 0.001* | |

| Shoulder function (SPADI function) | Baseline | 14.78 | 1.80 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | 2.50 | 2.70 | 0.353 |

| 6 months | −4.70 | 2.69 | 0.080 | |

| 9 months | −7.42 | 2.86 | 0.009* | |

| 12 months | −8.80 | 2.58 | 0.001* | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 8.57 | 2.48 | 0.001* |

| Missing at 12 months vs. no | 11.28 | 3.91 | 0.004* | |

| Shoulder pain and function (SPADI total) | Baseline | 16.85 | 1.61 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | 2.16 | 2.14 | 0.311 |

| 6 months | −5.94 | 2.11 | 0.005* | |

| 9 months | −7.96 | 2.25 | <0.001* | |

| 12 months | −9.72 | 2.09 | <0.001* | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 8.00 | 2.12 | <0.001* |

| Missing at 12 nonths vs. no | 11.82 | 3.49 | 0.001* | |

| Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) | Baseline | 25.46 | 0.40 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | −0.59 | 0.55 | 0.286 |

| 6 months | −0.77 | 0.57 | 0.176 | |

| 9 months | −0.20 | 0.63 | 0.749 | |

| 12 months | −0.96 | 0.58 | 0.098 | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.225 |

| Missing at 12 months vs. no | 1.82 | 0.90 | 0.044* | |

| Quality of life – physical (WOSI physical) | Baseline | 336.30 | 18.22 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | −64.36 | 20.47 | 0.002* |

| 6 months | −93.51 | 19.81 | <0.001* | |

| 9 months | −127.77 | 21.39 | <0.001* | |

| 12 months | −137.44 | 19.29 | <0.001* | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 58.52 | 26.82 | 0.029* |

| Missing at 12 months vs. no | 43.91 | 39.80 | 0.270 | |

| Quality of life – recreation (WOSI recreation) | Baseline | 168.37 | 9.53 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | −39.49 | 10.74 | <0.001* |

| 6 months | −66.41 | 10.57 | <0.001* | |

| 9 months | −78.16 | 11.68 | <0.001* | |

| 12 months | −82.38 | 10.97 | <0.001* | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 30.46 | 13.98 | 0.029* |

| Missing at 12 months vs. no | 35.60 | 20.75 | 0.085 | |

| Quality of life – life (WOSI life) | Baseline | 138.52 | 8.45 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | −32.43 | 9.51 | 0.001* |

| 6 months | −52.03 | 9.31 | <0.001* | |

| 9 months | −61.39 | 10.21 | <0.001* | |

| 12 months | −71.26 | 9.49 | <0.001* | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 14.98 | 12.25 | 0.221 |

| Missing at 12 months vs. no | 7.91 | 18.39 | 0.667 | |

| Quality of life – emotion (WOSI emotion) | Baseline | 143.39 | 6.95 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | −30.00 | 8.88 | 0.001* |

| 6 months | −39.40 | 8.80 | <0.001* | |

| 9 months | −52.40 | 9.73 | <0.001* | |

| 12 months | −57.99 | 8.99 | <0.001* | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 28.71 | 10.55 | 0.007* |

| Missing at 12 months vs. No | 15.28 | 15.34 | 0.319 | |

| Quality of life (WOSI total) | Baseline | 784.65 | 39.89 | |

| Time (reference = baseline) | 3 months | −177.98 | 44.01 | <0.001* |

| 6 months | −244.92 | 43.44 | <0.001* | |

| 9 months | −318.73 | 47.68 | <0.001* | |

| 12 months | −332.33 | 44.58 | <0.001* | |

| Recurrent Status | Recurrent vs. non-recurrent | 140.10 | 59.15 | 0.018* |

| Missing at 12 months vs. no | 99.90 | 86.96 | 0.251 | |

SPADI: Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (range 0–100, higher scores denote worse pain and function), TSK-11: Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia 11 (range 11–44, higher scores denote worse kinesiophobia), SAS: Shoulder Activity Scale (range 0–20, higher score denotes increased activity level), WOSI: Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (range 0–2100, higher scores denote worse quality of life).

Significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) was not significantly different in people with recurrent shoulder instability compared to those who did not suffer recurrence (Table 2). Shoulder-related quality of life (WOSI total) was significantly decreased in people who had recurrent shoulder instability when compared to those who had no recurrent episodes (Table 2). Higher WOSI scores indicate worse quality of life. Physical, recreational and emotion quality of life domains, of the WOSI, were significantly decreased in those people who had recurrent shoulder instability compared to those who had no recurrent episodes (Table 2). Post-hoc power analysis with respect to recurrent instability status showed results for the difference in TSK-11 and SPADI-pain were powered at 66%, while results for differences in WOSI scores were powered at 91%.

To assess how these outcome variables changed over the following 12 months for the entire cohort who had an FTASD: Across the cohort, shoulder activity decreased significantly at three and six months after injury. Compared with pre-injury values, there was no significant difference at 9 and 12 months after an FTASD (p > 0.05). Levels of shoulder pain (SPADI pain) decreased significantly across all time periods compared to the level of shoulder pain experienced after the FTASD (Table 2). Shoulder function (SPADI function) improved over time and was significantly better compared to baseline at 9 and 12 months (p < 0.01 and p < 0.00, respectively) (Table 2). There was no statistically significant change in kinesiophobia (TSK-11) across all time points compared with baseline (Table 2). Quality of life (WOSI scores) was significantly improved across all time points when compared to baseline values (Table 2).

Discussion

This study sought to examine patient-reported outcome measures for people following an FTASD and to see whether these variables changed over time. This study has shown that quality of life and shoulder pain were significantly affected in people who reported recurrent shoulder instability at 12 months after an FTASD. Kinesiophobia did not significantly change over time within 12 months after an FTASD.

To examine the level of quality of life, pain and disability, and kinesiophobia after an FTASD within 12 weeks: For the entire cohort (irrespective of whether they went on to develop recurrent shoulder instability), the immediate (within 12 weeks) influence of an FTASD was significant. Quality of life, kinesiophobia and shoulder pain and function were all negatively influenced. Other authors have reported a negative impact of a shoulder dislocation on quality of life,19 shoulder pain7 and kinesiophobia.11,14 This finding speaks to objective one of this study, where the descriptive analysis of these patient-reported variables indicated the detrimental impact of an FTASD. Clinicians commonly examine levels of pain and dysfunction in people with an FTASD.20 They should also be aware of the immediate impact of an FTASD on quality of life, and kinesiophobia, and adjust their assessment and treatment accordingly.

To examine whether these variables were different in people with and without recurrent shoulder instability over the following year: Those people who went on to have recurrent shoulder instability had significantly greater levels of shoulder pain compared to the group without recurrence. There was no difference in kinesiophobia in those who had recurrent shoulder instability compared with those who did not, which is in agreement with the findings of Eshoj et al.14 Quality of life was decreased in people with recurrent shoulder instability, which indicated the significant impact that recurrent shoulder instability has on an individual. Thus, low rates of recurrent instability and improving quality of life one year after an FTASD in this cohort indicates that primary shoulder stabilisation is unwarranted.

To assess how these outcome variables changed over the following 12 months for the entire cohort who had an FTASD: When looking across the entire cohort of people who had suffered an FTASD, shoulder function was significantly improved at nine months after an FTASD when compared with initial injury levels. Shoulder pain steadily improved from baseline and was improved at all time points from the initial injury. There was a statistically significant improvement in quality of life from baseline at all time points over the entire 12 months. There was a statistically significant decrease in shoulder activity levels from pre-injury levels at both three and six months post-injury. However, shoulder activity levels were not significantly different from pre-injury levels at 9 and 12 months post-injury, which indicated a return to similar pre-injury activity levels. Overall, kinesiophobia did not significantly change across the entire 12 months. While quality of life, pain, function and shoulder activity in the total cohort improved across time, kinesiophobia in the total cohort showed no statistically significant decrease across the 12 months following an FTASD. This is in contrast to Johnston and Carroll21 who reported a ‘U’ effect where kinesiophobia was affected initially after an injury, improved over time with treatment and then worsened again as people planned to returned to sport.21 However, Johnston and Carroll21 specifically studied athletes who were returning to sport, while the population in our study was a general population that included both sporting and non-sporting people.

Other relevant findings

Parr et al.22 reported TSK-11 scores in males and females prior to a painful stimulus (males 18.00 (4.98) and females 17.99 (3.96)) and 48 h after exercise-induced pain (males 18.59 (5.38) and females 19.19 (4.96)). Prugh et al.23 reported that people with elbow valgus overload scored a TSK-11 of 20, while those with traumatic elbow hyperextension scored 26 of the TSK-11. The mean TSK-11 score at baseline in our study in people with an FTASD (25.92) was higher when compared with people without sudden onset traumatic injuries22 but similar to people with traumatic elbow injuries.23

A possible explanation for the elevated TSK-11 levels at baseline and across time is that the traumatic nature of the injury resulted in increased levels of kinesiophobia. Alternatively, the TSK-11 score may not be a responsive measure of change in kinesiophobia over time in a population of people with an acute FTASD.

When compared to other people with anterior shoulder instability, the quality of life scores in this study (WOSI: 65.7% ± 22.4%) were higher than other studies which have examined quality of life in people with anterior shoulder instability (50.8% ± 21.5%24) and those about to undergo shoulder stabilisation surgery (43.3% ± 19.9%25). Both these studies reported quality of life in people who were presenting for further medical intervention, while our study measured quality of life in all people who had had an FTASD. People who present for medical intervention following an FTASD may have poorer quality of life and be different from the total population of people who have suffered an FTASD. The levels of quality of life in this study one year after a dislocation (65.7% ± 22.4%) were slightly lower than those reported following anterior shoulder stabilisation (76% ± 21%) at least two years after the surgery. Given that the MCID for the WOSI is 220 (10.4%),26 and that the WOSI trajectory was improving at one year follow-up, there appears to be little justification for surgical intervention for people with an FTASD to improve quality of life. The SPADI has not been widely used in people with shoulder instability.27 The SPADI total scores in our population with an FTASD were 20.82 shortly after their FTASD and decreased to 8.37 at 12 months following their injury, indicating decreased levels of shoulder pain and dysfunction over this time period.

This study had a number of limitations. Considerable effort was made to establish contact with all participants at each follow-up point. However, continual contact with a relatively young mobile population across the 12-month follow-up period was difficult. New Zealanders have high migration rates28 and this may have contributed to these challenges. While we were able to contact 186 of the original 213 participants to establish the presence of recurrent shoulder instability, only 86 were willing to answer questionnaires to record the patient-reported outcomes. People who did not complete questionnaires at 12 months had significantly different levels of shoulder pain and function and kinesiophobia at baseline (Table 2). It was not possible to establish whether the people who did not want to answer the questionnaires were different from those who did at the time of contact. For example, those that did respond may not accurately represent the quality of life, shoulder pain and disability, level of activity and kinesiophobia for the entire available cohort at each time point. Additionally, other unmeasured variables such as level of education and number of hours worked in a week may have influenced a person’s willingness to complete the questionnaires.

Post-hoc analysis for 12-month follow-up data demonstrated that with 86 participants we were sufficiently powered to detect a difference between recurrent instability status only for quality of life analysis (91%). This study was not adequately powered for analyses of shoulder pain (66%) or kinesiophobia (66%) and had limited power for shoulder function (4%), SPADI total scores (23%) or shoulder activity (5%). Therefore, further studies of larger sample size are required to examine the effect of recurrent shoulder instability in those managed non-operatively. However, the study was powered at 85% to assess change over time in the entire cohort of people with an FTASD, regardless of instability status.

There may be some systemic measurement error as the questionnaires may not have accurately measured these psychosocial variables. Self-reported questionnaires are proxy measures of an individual’s actual state, as these measures, by their very nature, are unobservable and must be inferred.29,30 Additionally, limitations in the capture of intended constructs may have arisen. For example, as the SAS measures only the frequency of activity, people who were engaged for intense efforts of activity on a weekly basis would score lower in activity level than a person who engaged in moderate levels of activity on a daily basis. Additionally, the SAS was recorded retrospectively, as a measure of pre-injury status. Therefore, the SAS may not accurately represent shoulder activity levels in this population.

Undertaking this study throughout all of New Zealand necessitated the recording of data over the telephone. This precluded the addition of clinical tests such as an apprehension test as a baseline variable. Future studies should examine whether a positive apprehension test impacts on quality of life and kinesiophobia. Further studies should also examine whether the presence or size of a labral tear affects quality of life, shoulder pain and function, and kinesiophobia in a non-operative population. Future studies could also examine whether kinesiophobia is significantly different in people managed operatively or non-operatively.

Conclusions

Quality of life and shoulder pain were significantly affected in people who reported recurrent shoulder instability 12 months following an FTASD. In the entire cohort of people with an FTASD, kinesiophobia did not significantly change across the 12 months following an FTASD and may require longer follow-up.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in this study for sharing the story of their FTASD with us. This work has been presented previously at the New Zealand Shoulder and Elbow Conference, July 2019.

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Auckland University of Technology, Shoulder and Elbow Physiotherapy Australasia, New Zealand Sports Medicine-Auckland Branch and New Zealand Manipulative Physiotherapy Association.

ORCID iD: M Olds https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2067-6924

Ethical Review and Patient Consent

Ethical approval was obtained from Auckland University of Ethics Committee (AUTEC), approval number #14/256.

References

- 1.te Slaa RL, Wijffels MPJM, Brand R, et al. A prospective arthroscopic study of acute first-time anterior shoulder dislocation in the young: a five-year follow-up study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12: 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marans HJJ, Angel KRR, Schemitsch EHH, et al. The fate of traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74: 1242–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wasserstein DN, Sheth U, Colbenson K, et al. The true recurrence rate and factors predicting recurrent instability after nonsurgical management of traumatic primary anterior shoulder dislocation: a systematic review. Arthroscopy 2016; 32: 2616–2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olds M, Ellis R, Donaldson K, et al. Risk factors which predispose first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocations to recurrent instability in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2015; 49: 913–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenters TR, Franta AK, Wolf FM, et al. Arthroscopic compared with open repairs for recurrent anterior shoulder instability. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89: 244–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hovelius L, Olofsson A, Sandström B, et al. Nonoperative treatment of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in patients forty years of age and younger. a prospective twenty-five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90: 945–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachs RA, Lou SM, Paxton E, et al. Can the need for future surgery for acute traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation be predicted? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89: 1665–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerometta A, Klouche S, Herman S, et al. The shoulder instability-return to sport after injury (SIRSI): a valid and reproducible scale to quantify psychological readiness to return to sport after traumatic shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018; 26: 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkley A, Werstine R, Ratjek A, et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of immediate arthroscopic stabilization versus immobilization and rehabilitation in first traumatic anterior dislocations of the shoulder: long-term evaluation. Arthroscopy 2005; 21: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson CM, Howes J, Murdoch H, et al. Functional outcome and risk of recurrent instability after primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in young patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88: 2326–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tjong VK, Devitt BM, Murnaghan ML, et al. A qualitative investigation of return to sport after arthroscopic bankart repair: beyond stability. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43: 2005–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozturk B, Maak T, Fabricant P, et al. Return to sports after arthroscopic stabilization in patients aged younger than 25 years. Arthroscopy 2013; 29: 1922–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parr JJ, Borsa P, Fillingim R, et al. Psychological influences predict recovery following exercise induced shoulder pain. Int J Sports Med 2014; 35: 232–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eshoj H, Rasmussen S, Frich LH, et al. Patients with non-operated traumatic primary or recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation have equally poor self-reported and measured shoulder function : a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019; 20: 59–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olds M, Donaldson K, Ellis R, et al. In children 18 years and under, what promotes recurrent shoulder instability after traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation? A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50: 1135–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkley A, Griffin S, McLintock H, et al. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability: The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Am J Sports Med 1998; 26: 764–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, et al. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res 1991; 4: 143–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, et al. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: a shortened version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia. Pain 2005; 117: 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickens JF, Owens BD, Cameron KL, et al. Return to play and reccurent instability after in season anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42: 2842–2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma R, Brimmo OA, Li X, et al. Current concepts in rehabilitation for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2017, pp. 499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston LH, Carroll D. The context of emotional responses to athletic injury: a qualitative analysis. J Sport Rehabil 1998; 7: 206–220. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parr JJ, Borsa PA, Fillingim RB, et al. Pain-related fear and catastrophizing predict pain intensity and disability independently using an induced muscle injury model. J Pain 2012; 13: 370–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prugh J, Zeppieri G, George SZ. Impact of psychosocial factors, pain, and functional limitations on throwing athletes who return to sport following elbow injuries: a case series. Physiother Theory Pract 2012; 28: 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham G, Zanchi D, Emmert K, et al. Neural correlates of clinical scores in patients with anterior shoulder apprehension. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015; 47: 2612–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraeutler MJ, McCarty EC, Belk JW, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of the MOON shoulder instability cohort. Am J Sports Med 2018; 46: 1064–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkley A, Griffin S, Dainty K. Scoring systems for the functional assessment of the shoulder. Arthroscopy 2003; 19: 1109–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buteau JL, Eriksrud O, Hasson SM. Rehabilitation of a glenohumeral instability utilizing the body blade. Physiother Theory Pract 2007; 23: 333–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Statistics New Zealand. Migration, New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkinson MJ, Lennox RD. Extending basic principles of measurement models to the design and validation of Patient Reported Outcomes. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006; 4: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1994. [Google Scholar]