Abstract

BACKGROUND

Signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) is an uncommon subtype in colorectal cancer (CRC), with a short survival time. Therefore, it is imperative to establish a useful prognostic model. As a simple visual predictive tool, nomograms combining a quantification of all proven prognostic factors have been widely used for predicting the outcomes of patients with different cancers in recent years. Until now, there has been no nomogram to predict the outcome of CRC patients with SRCC.

AIM

To build effective nomograms for predicting overall survival (OS) and cause-specific survival (CSS) of CRC patients with SRCC.

METHODS

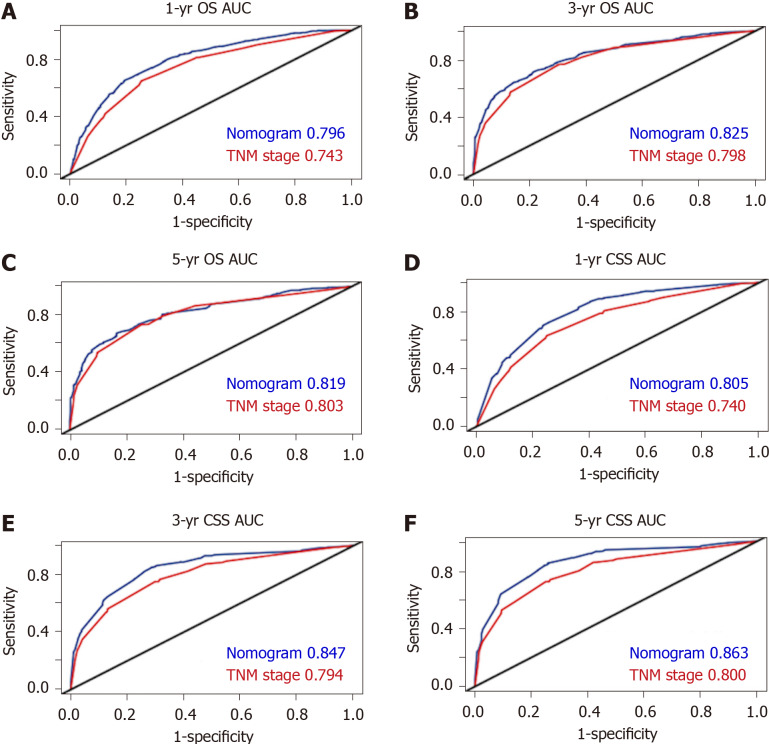

Data were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database between 2004 and 2015. Multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to identify independent variables for both OS and CSS to construct the nomograms. Performance of the nomograms was assessed by concordance index, calibration curves, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. ROC curves were also utilized to compare benefits between the nomograms and the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system. Patients were classified as high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups using the novel nomograms. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted to compare survival differences.

RESULTS

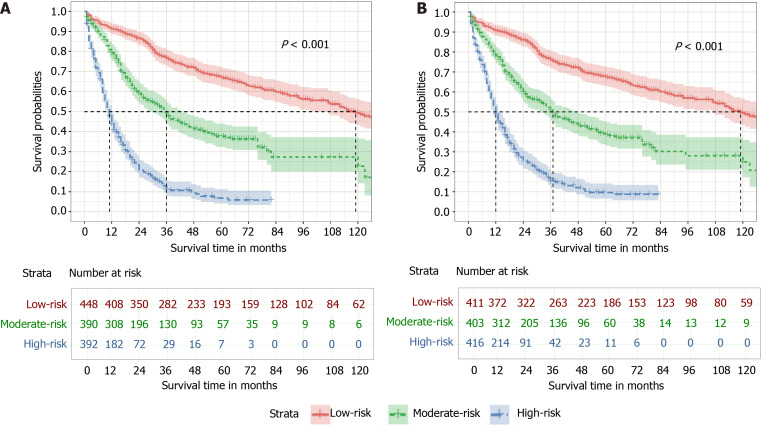

In total, 1230 patients were included. The concordance index of the nomograms for OS and CSS were 0.737 (95% confidence interval: 0.728-0.747) and 0.758 (95% confidence interval: 0.738-0.778), respectively. The calibration curves and ROC curves demonstrated good predictive accuracy. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year area under the curve values of the nomogram for predicting OS were 0.796, 0.825 and 0.819, in comparison to 0.743, 0.798, and 0.803 for the TNM staging system. In addition, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year area under the curve values of the nomogram for predicting CSS were 0.805, 0.847 and 0.863, in comparison to 0.740, 0.794, and 0.800 for the TNM staging system. Based on the novel nomograms, stratified analysis showed that the 5-year probability of survival in the high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups was 6.8%, 37.7%, and 67.0% for OS (P < 0.001), as well as 9.6%, 38.5%, and 67.6% for CSS (P < 0.001), respectively.

CONCLUSION

Convenient and visual nomograms were built and validated to accurately predict the OS and CSS rates for CRC patients with SRCC, which are superior to the conventional TNM staging system.

Keywords: Colorectal carcinoma, Signet ring cell carcinoma, Nomogram, Overall survival, Cause-specific survival, Prognosis

Core Tip: Using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database between 2004 and 2015, convenient and visual nomograms were built and validated to accurately predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival and cause-specific survival rates for signet ring cell carcinoma in colorectal cancer patients for the first time. The novel nomograms stratified patients into high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups with 5-year probability survival of 6.8%, 37.7%, and 67.0% for overall survival (P < 0.001), as well as 9.6%, 38.5%, and 67.6% for cause-specific survival (P < 0.001), respectively. Besides, these nomograms were proved to be superior to the conventional tumor-node-metastasis staging system.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, in spite of a continuous decline of its incidence and mortality[1]. Approximately 147950 people will be diagnosed with CRC and 53200 deaths due to this disease will occur in the United States this year[2].

CRC represents a group of histopathological heterogeneous diseases, and the largest number of cases are adenocarcinomas. Signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) is an uncommon subtype constituting less than 1% of CRC cases, and it is characterized by abundant intracytoplasmic mucin pushing the nucleus aside[3-5].

In spite of fast development of treatment methods recently, SRCC is still regarded as a different clinical entity due to its shorter survival compared with adenocar-cinoma[6-9]. To evaluate the prognostic factors of SRCC in CRC patients and to establish individualized treatment strategies, it is imperative to establish a useful prognostic model.

The most widely used prognostic tool for CRC patients is the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system[10]. However, clinical factors, for instance, gender, tumor size, primary tumor location, and pathological grade, might also affect patient survival. However, limited information is available regarding the survival and prognostic factors of SRCC in CRC patients. As a simple visual predictive tool, nomograms combining and quantitating all proven prognostic factors have been widely used for predicting the outcomes of different cancers in recent years[11-14]. Until now, there has been no nomogram to predict the outcome of CRC patients with SRCC.

The aim of this study was to build convenient and effective nomograms for predicting the outcomes of CRC patients with SRCC using data extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

This retrospective study was based on the SEER database from 2004 to 2015, which accounts for approximately 28% of the United States population. Before accessing the data, permission was obtained in advance. Data were extracted using SEER*Stat software.

Patient selection

Patients diagnosed with SRCC were identified by the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3) code 8490. Patients were excluded if non-SRCC appeared in the pathology report or if CRC was not their only primary tumor. Patients with a follow-up period or survival time of less than 1 mo were also excluded. In our study, 11 variables were collected from the SEER database, consisting of year of diagnosis, age, gender, marital status, pathological grade, tumor size, primary site, surgery, T stage, N stage, and M stage. TNM stage was according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer seven edition staging system. Patients with complete information of the above 11 variables were included.

As continuous variables, the cutoff value of age was 60 years. The patients were divided into three groups based on the tumor size (< 2 cm, 2-4 cm, and ≥ 4 cm). In addition, the primary sites were categorized as the right-side colon [containing the cecum (C18.0), ascending colon (C18.2), hepatic flexure (C18.3), and transverse colon (C18.4)] and left-side colon [containing the splenic flexure (C18.5), descending colon (C18.6), sigmoid colon (C18.7), rectosigmoid (C19.9), and rectum (C20.9)].

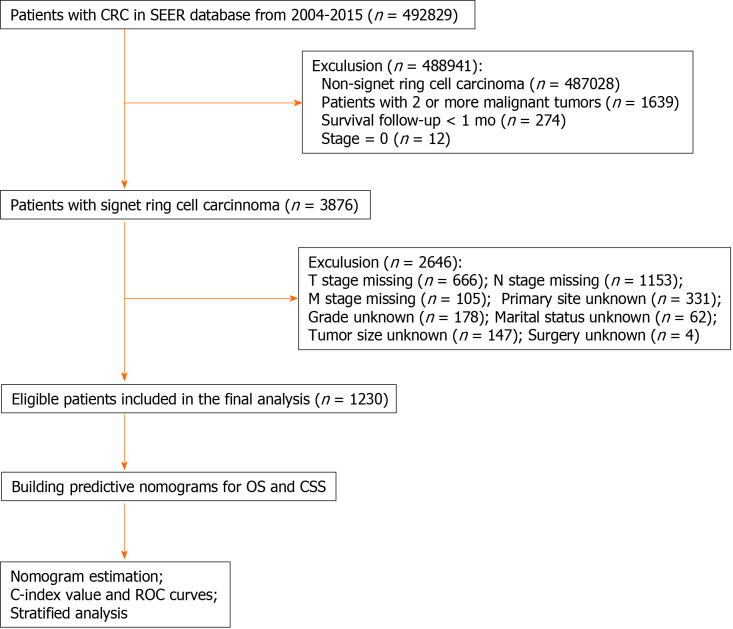

Finally, 1230 CRC patients who were diagnosed with SRCC from 2004 to 2015 were obtained. Figure 1 shows the workflow chart for patient selection.

Figure 1.

Workflow of patient selection and establishment of nomograms to predict overall survival and cause-specific survival. CRC: Colorectal cancer; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis; OS: Overall survival; CSS: Cause-specific survival; C-index: Concordance index; ROC: Receiver operating characteristic.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) and cause-specific survival (CSS) were calculated according to deaths due to any cause or CRC, respectively. Censored data were defined as patients who were still alive or died of other reasons before the end of the study. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and CSS rates; and univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to identify the independent variables of both OS and CSS, performed using SPSS software (Version 22.0; IBM Corporation). R software (version 3.6.0) was applied to establish nomograms based on the potential prognostic variables related to OS and CSS on the basis of the Cox regression model. The discriminatory power of the nomograms was assessed by the concordance index (C-index) value and the time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year ROC curves were utilized to distinguish the predictive ability of the nomogram over time, as well as to compare the benefits between the nomograms and the TNM staging system. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value < 0.05.

Risk stratification according to novel nomograms

Risk stratification was performed based on the novel nomograms. The study divided all patients into three groups (high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk) based on tertiles of the total scores. The Kaplan-Meier method was utilized to generate survival curves for the three risk groups, which were compared by the log-rank test.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics and survival outcomes

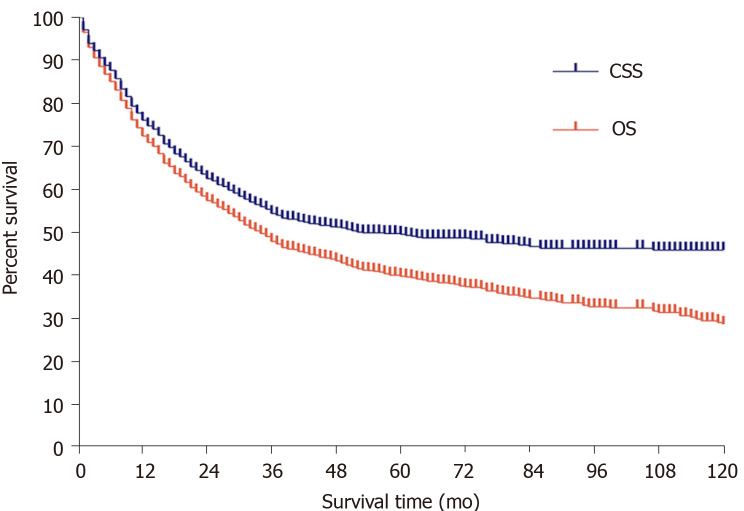

The patient characteristics as well as the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and CSS rates are shown in Table 1. Among the 1230 patients, the majority were ≥ 60 years (64.6%), male (51.3%), and married (55.5%). With regard to the pathological grade, most patients had poorly or undifferentiated SRCC with grades III (75.4%) and IV (17.1%). As to the primary site, 65.5% of patients had right-side colon cancer, while 23.0% had left-side colon cancer and 11.5% had rectal cancer. In total, approximately three-quarters (75.4%) of the patients had a tumor size ≥ 4 cm in diameter, after that 20.0% with a tumor size ranging from 2 cm to 4 cm and 4.6% with a tumor size < 2 cm. Moreover, a small number (5.1%) of patients received surgery, including local or partial resection and total resection. TNM stages I, II, III, and IV tumors made up 7.7%, 28.1%, 41.9%, and 22.3%, respectively. The OS and CSS rates at 1-, 3-, 5-years were 72.5%, 47.9%, and 39.8% and 76.1%, 54.4%, and 49.6%, respectively (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and 1-, 3-, and 5-yr overall survival and cause-specific survival rates

|

Characteristic

|

n

|

%

|

OS (%)

|

CSS (%)

|

||||

|

1-yr

|

3-yr

|

5-yr

|

1-yr

|

3-yr

|

5-yr

|

|||

| Age (yr) | ||||||||

| < 60 | 436 | 35.4 | 78.7 | 49.9 | 41.5 | 78.4 | 52.3 | 44.8 |

| ≥ 60 | 794 | 64.6 | 72.0 | 46.9 | 39.0 | 74.9 | 55.6 | 52.2 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 631 | 51.3 | 74.4 | 45.8 | 39.2 | 76.3 | 51.3 | 46.8 |

| Female | 599 | 48.7 | 74.3 | 50.1 | 40.6 | 76.0 | 57.8 | 52.5 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 683 | 55.5 | 78.1 | 51.8 | 43.4 | 79.2 | 56.2 | 51.5 |

| Unmarried | 547 | 44.5 | 69.7 | 44.4 | 36.1 | 72.3 | 52.3 | 47.2 |

| Primary site | ||||||||

| Left side colon | 806 | 65.5 | 73.9 | 49.6 | 41.2 | 76.5 | 57.3 | 52.9 |

| Right side colon | 282 | 22.9 | 74.0 | 46.1 | 38.7 | 75.8 | 51.1 | 46.0 |

| Rectum | 142 | 11.5 | 72.4 | 42.7 | 34.5 | 75.0 | 45.6 | 38.9 |

| Pathological grade | ||||||||

| I-II | 93 | 7.6 | 76.3 | 60.2 | 51.6 | 80.2 | 66.8 | 60.5 |

| III | 927 | 75.4 | 72.3 | 49.0 | 40.4 | 75.7 | 55.2 | 50.7 |

| IV | 210 | 17.1 | 71.5 | 36.8 | 31.4 | 76.1 | 44.5 | 38.8 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||||

| < 2 | 57 | 4.6 | 93.0 | 73.8 | 63.4 | 96.4 | 81.8 | 75.7 |

| 2-4 | 246 | 20.0 | 83.6 | 54.6 | 44.4 | 86.8 | 59.4 | 54.0 |

| ≥ 4 | 927 | 75.4 | 68.2 | 44.5 | 37.1 | 72.0 | 51.4 | 46.7 |

| T stage | ||||||||

| T1 | 55 | 4.5 | 80.0 | 70.1 | 59.0 | 81.5 | 71.4 | 60.1 |

| T2 | 77 | 6.3 | 92.2 | 77.2 | 65.8 | 94.8 | 86.7 | 83.5 |

| T3 | 607 | 49.3 | 80.0 | 59.7 | 52.0 | 84.2 | 67.4 | 63.5 |

| T4 | 491 | 39.9 | 59.1 | 25.7 | 17.3 | 62.4 | 30.3 | 23.5 |

| N stage | ||||||||

| N0 | 467 | 38.0 | 86.3 | 70.4 | 61.4 | 90.3 | 79.0 | 75.4 |

| N1 | 231 | 18.8 | 75.1 | 45.7 | 36.4 | 78.6 | 52.5 | 46.2 |

| N2 | 532 | 43.3 | 59.1 | 27.5 | 19.6 | 62.4 | 31.4 | 24.6 |

| M stage | ||||||||

| M0 | 956 | 77. | 80.6 | 58.0 | 48.7 | 84.8 | 65.7 | 60.4 |

| M1 | 274 | 22.3 | 44.1 | 9.9 | 6.0 | 46.0 | 11.8 | 8.0 |

| TNM stage | ||||||||

| I | 95 | 7.7 | 91.6 | 80.9 | 68.9 | 93.6 | 86.1 | 80.7 |

| II | 346 | 28.1 | 87.8 | 71.4 | 62.7 | 92.6 | 81.4 | 78.0 |

| III | 515 | 41.9 | 76.1 | 43.9 | 33.7 | 77.8 | 50.0 | 42.1 |

| IV | 274 | 22.3 | 44.1 | 9.9 | 6.0 | 46.0 | 11.8 | 8.0 |

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Yes | 63 | 5.1 | 74.6 | 50.3 | 41.8 | 78.2 | 56.9 | 51.8 |

| No | 1167 | 94.9 | 33.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 36.9 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

OS: Overall survival; CSS: Cause-specific survival; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

Figure 2.

Overall survival and cause-specific survival curves of all patients. OS: Overall survival; CSS: Cause-specific survival.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

In terms of OS, univariate analysis demonstrated that age, marital status, pathological grade, tumor size, surgery, T stage, N stage, and M stage were statistically significantly correlated with the prognosis (P < 0.05) (Table 2). These prognostic factors were entered into a Cox model for multivariate analysis. The following seven factors were considered independent prognostic factors for OS: Age (P < 0.001), marital status (P = 0.007), tumor size (P = 0.001), surgery (P < 0.001), T stage (P < 0.001), N stage (P < 0.001), and M stage (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of overall survival

|

Characteristic

|

HR

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| Age (yr) | 0.024 | ||

| < 60 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 1.199 | 1.024-1.405 | |

| Gender | 0.643 | ||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.966 | 0.833-1.119 | |

| Marital status | 0.004 | ||

| Married | 1 | ||

| Unmarried | 1.239 | 1.069-1.437 | |

| Primary site | 0.765 | ||

| Left side colon | 1 | ||

| Right side colon | 1.02 | 0.853-1.221 | |

| Rectum | 1.089 | 0.866-1.369 | |

| Pathological grade | 0.002 | ||

| I-II | 1 | ||

| III | 1.478 | 1.083-2.018 | |

| IV | 1.849 | 1.307-2.614 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 2 | 1 | ||

| 2-4 | 1.727 | 1.077-2.769 | |

| ≥ 4 | 2.433 | 1.557-3.802 | |

| T stage | < 0.001 | ||

| T1 | 1 | ||

| T2 | 0.707 | 0.406-1.231 | |

| T3 | 1.193 | 0.787-1.808 | |

| T4 | 2.839 | 1.875-4.300 | |

| N stage | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | 1 | ||

| N1 | 2.023 | 1.607-2.546 | |

| N2 | 3.458 | 2.879-4.154 | |

| M stage | < 0.001 | ||

| M0 | 1 | ||

| M1 | 3.729 | 3.158-4.403 | |

| Surgery | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 0.648 | 0.591-0.710 |

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox regression model analysis of overall survival

|

Characteristic

|

HR

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| Age (yr) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 60 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 1.714 | 1.457-2.017 | |

| Marital status | 0.007 | ||

| Married | 1 | ||

| Unmarried | 1.227 | 1.058-1.422 | |

| Pathological grade | 0.337 | ||

| I-II | |||

| III | |||

| IV | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.001 | ||

| < 2 | 1 | ||

| 2-4 | 1.326 | 0.81-2.171 | |

| ≥ 4 | 1.786 | 1.113-2.867 | |

| T stage | < 0.001 | ||

| T1 | 1 | ||

| T2 | 0.739 | 0.416-1.309 | |

| T3 | 0.881 | 0.562-1.381 | |

| T4 | 1.347 | 0.852-2.128 | |

| N stage | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | 1 | ||

| N1 | 1.599 | 1.258-2.034 | |

| N2 | 2.767 | 2.237-3.421 | |

| M stage | < 0.001 | ||

| M0 | 1 | ||

| M1 | 2.092 | 1.732-2.527 | |

| Surgery | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 0.29 | 0.214-0.393 |

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

In terms of the CSS, in the univariate analysis, the significant variables included primary site, pathological grade, tumor size, surgery, T stage, N stage, and M stage (P < 0.05) (Table 4). Multivariate analysis showed that five variables were still independent prognostic factors for CSS: Tumor size (P = 0.001), surgery (P < 0.001), T stage (P < 0.001), N stage (P < 0.001), and M stage (P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of cause-specific survival

|

Characteristic

|

HR

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| Age (yr) | 0.399 | ||

| < 60 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 0.928 | 0.78-1.104 | |

| Gender | 0.117 | ||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 0.874 | 0.738-1.034 | |

| Marital status | 0.075 | ||

| Married | 1 | ||

| Unmarried | 1.165 | 0.985-1.380 | |

| Primary site | 0.043 | ||

| Left side colon | 1 | ||

| Right side colon | 0.743 | 0.581-0.951 | |

| Rectum | 0.858 | 0.649-1.134 | |

| Pathological grade | 0.005 | ||

| I-II | 1 | ||

| III | 1.45 | 1.012-2.079 | |

| IV | 1.872 | 1.259-2.783 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 2 | 1 | ||

| 2-4 | 2.593 | 1.352-4.975 | |

| ≥ 4 | 3.651 | 1.95-6.835 | |

| T stage | < 0.001 | ||

| T1 | 1 | ||

| T2 | 0.366 | 0.174-0.769 | |

| T3 | 0.993 | 0.62-1.59 | |

| T4 | 2.807 | 1.764-4.467 | |

| N stage | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | 1 | ||

| N1 | 2.704 | 2.052-3.563 | |

| N2 | 4.957 | 3.958-6.209 | |

| M stage | < 0.001 | ||

| M0 | 1 | ||

| M1 | 4.534 | 3.789-5.425 | |

| Surgery | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 0.631 | 0.573-0.696 |

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

Table 5.

Multivariate Cox regression model analysis of cause-specific survival

|

Characteristic

|

HR

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| Primary site | 0.112 | ||

| Left side colon | |||

| Right side colon | |||

| Rectum | |||

| Pathological grade | 0.382 | ||

| I-II | |||

| III | |||

| IV | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.001 | ||

| < 2 | 1 | ||

| 2-4 | 1.938 | 0.984-3.816 | |

| ≥ 4 | 2.509 | 1.297-4.855 | |

| T stage | < 0.001 | ||

| T1 | 1 | ||

| T2 | 0.362 | 0.169-0.774 | |

| T3 | 0.612 | 0.366-1.023 | |

| T4 | 0.968 | 0.576-1.626 | |

| N stage | < 0.001 | ||

| N0 | 1 | ||

| N1 | 1.968 | 1.475-2.624 | |

| N2 | 3.411 | 2.642-4.406 | |

| M stage | <0.001 | ||

| M0 | 1 | ||

| M1 | 2.198 | 1.796-2.689 | |

| Surgery | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 0.3 | 0.217-0.414 |

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

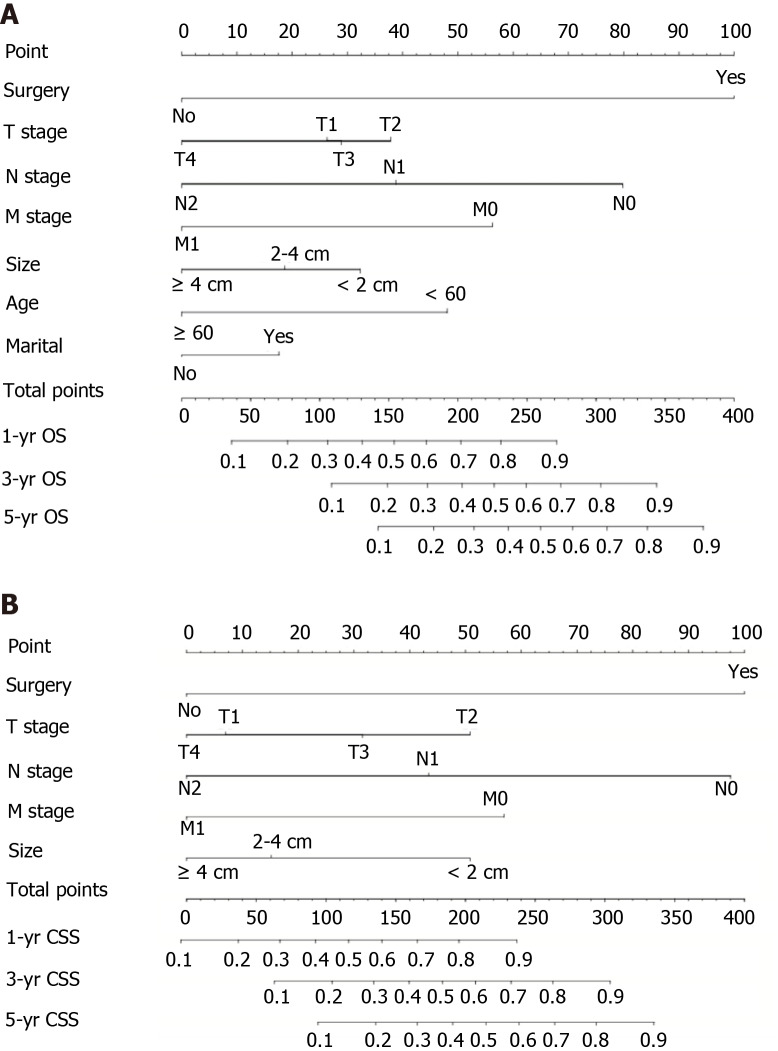

Construction and validation of prognostic prediction nomograms

Nomograms for OS and CSS were constructed on the basis of all independent variables in the multivariate analysis (Figure 3). Each variable was given a score, and the total score was obtained by summing the individual scores. As a visual and graphical prediction tool, nomograms allowed us to easily acquire the probability of the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and CSS of the patients.

Figure 3.

Nomograms for predicting overall survival and cause-specific survival. A: Nomogram based on the independent prognostic factors for the prediction of 1-, 3-, and 5-yr overall survival rates; B: Nomogram based on the independent prognostic factors for the prediction of 1-, 3-, and 5-yr cause-specific survival rates. OS: Overall survival; CSS: Cause-specific survival; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

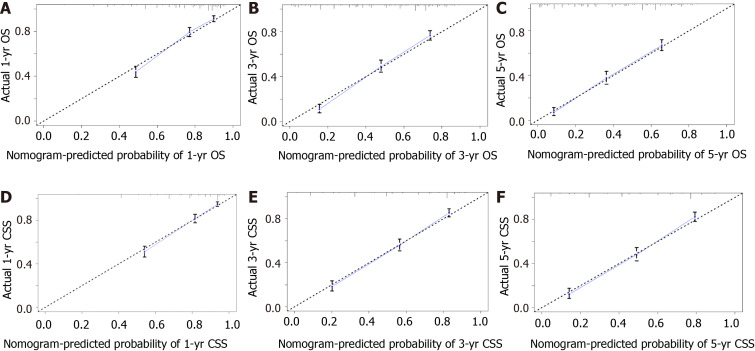

To assess the discriminatory power of the nomograms, C-index values were generated. C-index values of these novel models were 0.737 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.728-0.747] for OS and 0.758 (95%CI: 0.738-0.778) for CSS, which showed excellent accuracy. The calibration curves displayed in Figure 4 indicate a high degree of credibility, showing good consistency between the nomogram predictive values and the real observations for the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and CSS probabilities.

Figure 4.

Calibration plots. A-C: Calibration curves for predicting 1-yr (A), 3-yr (B), and 5-yr (C) overall survival rates; D-F: Calibration curves for predicting 1-yr (D), 3-yr (E), and 5-yr (F) cause-specific survival rates. OS: Overall survival; CSS: Cause-specific survival.

ROC analyses were carried out to compare the predictive efficacy of the nomograms to that of the TNM staging system. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year area under the curve (AUC) values of the nomogram for predicting the OS were 0.796, 0.825 and 0.819, in comparison to 0.743, 0.798 and 0.803 for the TNM staging system (Figure 5A-C). In addition, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year AUC values of the nomogram for predicting CSS were 0.805, 0.847 and 0.863, in comparison to 0.740, 0.794, and 0.8 for the TNM staging system (Figure 5D–F).

Figure 5.

Areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves for predicting overall survival and cause-specific survival. A-C: Area under the curve values of the nomogram and the tumor-node-metastasis staging system for predicting 1-yr (A), 3-yr (B), and 5-yr (C) overall survival rates; D-F: Area under the curve values of the nomogram and the tumor-node-metastasis staging system for predicting 1-yr (D), 3-yr (E), and 5-yr (F) cause-specific survival rates. AUC: Areas under the curve; OS: Overall survival; CSS: Cause-specific survival; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

Risk stratification according to novel prognostic nomograms

All 1230 patients were divided into three subgroups (high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk) based on tertiles of total scores in the novel nomograms. Survival curves were generated and are shown in Figure 6. In the OS cohort, 5-year OS rates in the high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups were 6.8%, 37.7%, and 67.0%, respectively. In the CSS cohort, 5-year CSS rates in the high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups were 9.6%, 38.5%, and 67.6%, respectively. Survival outcomes among the three groups had a significant difference in terms of both OS (P < 0.001) and CSS (P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Risk assessment using the nomogram. A: Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival in the subgroup according to tertiles of the total score; B: Kaplan-Meier estimate of cause-specific survival in the subgroup according to tertiles of the total score.

DISCUSSION

As a graphical statistical prediction model, nomograms enable individualized predictions for clinicians to quantitatively assess the prognosis of patients[11]. This study first established effective nomograms, which accurately predicted 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and CSS probabilities of CRC patients with SRCC. The calibration curves demonstrated a high degree of credibility of the nomograms. Moreover, the nomogram was able to divide individuals into high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups, indicating that it could be a good tool to predict the outcomes of CRC patients with SRCC.

The TNM staging system is considered to be the foundation of prognostication in CRC[10]. Consistent with this, our study showed that T stage, N stage, and M stage were all significant prognostic variables for OS and CSS of CRC patients with SRCC. However, there was often a significant difference in the prognosis of patients with the same stage. The TNM staging system has several shortcomings in predicting personalized prognosis since it is lacking the patients’ characteristics, compared to nomograms that include all of the prognostic factors. In recent years, nomograms have been demonstrated to be more precise than the conventional TNM staging system in predicting the outcomes of patients with different solid tumors, including CRC, but little is known about SRCC in CRC patients[15-17].

In the present study, besides the TNM stage factors, tumor size and surgery were both independent prognostic factors for OS and CSS. Moreover, age and marital status were two independent prognostic factors but only for OS. These factors were all included in the nomograms for the prediction of OS and CSS. Using ROC curve analysis, these novel nomograms, which simplified and combined the TNM stage with other independent prognostic factors, showed better predictive accuracy and prognostic value compared to the conventional TNM staging system, and were easy to use and provided a quantitative prognostic assessment for individuals.

In several tumors, for instance, breast cancer, lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer, tumor size is incorporated into T stage and is closely associated with the cancer prognosis. However, it was not included in the TNM stage in CRC. Many studies have shown that a larger tumor size is associated with a shorter disease-free survival and worse OS in CRC[18-20]. Our study further subdivided tumor size into < 2 cm, 2-4 cm, and ≥ 4 cm, and validated its impact on prognosis. The results showed that large tumors were related to a poor prognosis. Though not included in the TNM system, tumor size was a crucial prognostic variable, which could not be ignored in clinical practice.

As we know, surgery is the established standard treatment for early stage CRC, as well as some metastases of CRC[21-23]. Multivariate analysis in our study showed that, in comparison with patients who received surgery, the hazard ratio (HR) for patients without surgery was 0.29 (95%CI: 0.214-0.393) for OS and 0.282 (95%CI: 0.203-0.391) for CSS of CRC patients with SRCC. This indicated that although the prognosis was relatively poor in SRCC, surgery is recommended to improve survival.

Many studies have demonstrated that marital status significantly influences the survival of CRC patients. Multivariate analysis in our research showed that in the subgroup of SRCC patients, marital status also affected OS (P = 0.007), which was consistent with the previous studies[15,24]. A similar phenomenon was found in terms of age. There have been reports that age is related to survival in CRC patients[10,16,17]. Our results indicated that patients older than 60 years had a shorter survival in comparison with younger patients with SRCC (P < 0.001).

The prognostic value of primary tumor location in metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma has been reported, with right-side colon cancer having a worse prognosis[25-28]. However, different results were reported for the SRCC subgroup of CRC. In our study, univariate analysis showed the 5-year CSS rates of SRCC in left-side colon, right-side colon, and rectum were 52.9%, 42.6%, and 38.9%, respectively (P = 0.043), which indicated that the primary tumor site might affect the prognosis of SRCC patients. Nevertheless, significant differences were not found between different locations in terms of both OS and CSS using multivariate analysis. A study that combined tumor location and stage in SRCC patients showed that a significant difference between tumor locations was only found in stage I-II disease, while rectal SRCC had the worst prognosis, which indicates that the correlation between survival and tumor locations in CRC is not straightforward[29]. Based on the previous research, stratified analysis by tumor stage or other factors might be needed when analyzing differences in survival between right-side colon, left-side colon, and rectal cancer in the SRCC subgroup in the future.

Our study does have some limitations, which should be taken into account when explaining the results. First, it was a retrospective analysis, which might cause selection biases. Second, treatment-related variables except for surgery, such as chemotherapy regimens and radiation doses, which might be closely related to survival, were not included. Third, the SEER database does not provide genomic characteristics (such as RAS, BRAF, microsatellite instability, and other genes’ statuses), which have been proven to influence survival; thus, these factors were not included in our analysis. Hence, prospective evaluation of the presented nomograms combined with other factors to improve this model is needed in clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, convenient and visual nomograms were built and validated with good accuracy and high credibility based on the SEER database. They could accurately predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS and CSS rates for CRC patients with SRCC. In addition, these nomograms were also demonstrated to be superior to the conventional TNM staging system with increased predictive accuracy but without increasing the complexity. However, due to this being a retrospective study, prospective validations will be required in the future.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) is an uncommon subtype of colorectal cancer (CRC) with short survival time. Several factors influence its prognosis. Until now, there has been no nomogram to predict the outcome of CRC patients with SRCC.

Research motivation

To explore the prognostic factors and build effective nomograms for predicting overall survival (OS) and cause-specific survival (CSS) of CRC patients with SRCC.

Research objectives

To build effective nomograms based on significant prognostic factors for predicting OS and CSS of CRC patients with SRCC.

Research methods

Data was extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database between 2004 and 2015. Multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to identify independent factors. Nomograms were built and validated to predict OS and CSS. Patients were divided into high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups using the novel nomograms.

Research results

In total, 1230 patients were included. Nomograms for OS and CSS were built with the concordance index of 0.737 and 0.758, respectively. The calibration curves and receiver operating characteristic curves demonstrated good predictive accuracy. The novel nomograms stratified patients into high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups with 5-year probability survival of 6.8%, 37.7%, and 67.0% for OS (P < 0.001), as well as 9.6%, 38.5%, and 67.6% for CSS (P < 0.001), respectively.

Research conclusions

Convenient and visual nomograms were constructed and validated to predict the OS and CSS rates for CRC patients with SRCC for the first time, which are superior to the conventional tumor-node-metastasis staging system.

Research perspectives

These novel nomograms could be used for accurately predicting survival rates of CRC patients with SRCC, as well as stratifying patients into different risk groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program for kindly providing the clinical data.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 7, 2020

First decision: January 25, 2021

Article in press: February 11, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: ELfishawy M S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Fu-Rong Kou, Department of Day Oncology Unit, Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Translational Research (Ministry of Education/Beijing), Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute, Beijing 100142, China.

Yang-Zi Zhang, Department of Radiation Oncology, Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Translational Research (Ministry of Education/Beijing), Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute, Beijing 100142, China.

Wei-Ran Xu, Department of Oncology, Peking University International Hospital, Beijing 102206, China. xiaoyao444444@126.com.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, Dicker DJ, Chimed-Orchir O, Dandona R, Dandona L, Fleming T, Forouzanfar MH, Hancock J, Hay RJ, Hunter-Merrill R, Huynh C, Hosgood HD, Johnson CO, Jonas JB, Khubchandani J, Kumar GA, Kutz M, Lan Q, Larson HJ, Liang X, Lim SS, Lopez AD, MacIntyre MF, Marczak L, Marquez N, Mokdad AH, Pinho C, Pourmalek F, Salomon JA, Sanabria JR, Sandar L, Sartorius B, Schwartz SM, Shackelford KA, Shibuya K, Stanaway J, Steiner C, Sun J, Takahashi K, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wagner JA, Wang H, Westerman R, Zeeb H, Zoeckler L, Abd-Allah F, Ahmed MB, Alabed S, Alam NK, Aldhahri SF, Alem G, Alemayohu MA, Ali R, Al-Raddadi R, Amare A, Amoako Y, Artaman A, Asayesh H, Atnafu N, Awasthi A, Saleem HB, Barac A, Bedi N, Bensenor I, Berhane A, Bernabé E, Betsu B, Binagwaho A, Boneya D, Campos-Nonato I, Castañeda-Orjuela C, Catalá-López F, Chiang P, Chibueze C, Chitheer A, Choi JY, Cowie B, Damtew S, das Neves J, Dey S, Dharmaratne S, Dhillon P, Ding E, Driscoll T, Ekwueme D, Endries AY, Farvid M, Farzadfar F, Fernandes J, Fischer F, G/Hiwot TT, Gebru A, Gopalani S, Hailu A, Horino M, Horita N, Husseini A, Huybrechts I, Inoue M, Islami F, Jakovljevic M, James S, Javanbakht M, Jee SH, Kasaeian A, Kedir MS, Khader YS, Khang YH, Kim D, Leigh J, Linn S, Lunevicius R, El Razek HMA, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Marcenes W, Markos D, Melaku YA, Meles KG, Mendoza W, Mengiste DT, Meretoja TJ, Miller TR, Mohammad KA, Mohammadi A, Mohammed S, Moradi-Lakeh M, Nagel G, Nand D, Le Nguyen Q, Nolte S, Ogbo FA, Oladimeji KE, Oren E, Pa M, Park EK, Pereira DM, Plass D, Qorbani M, Radfar A, Rafay A, Rahman M, Rana SM, Søreide K, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Sepanlou SG, Shaikh MA, She J, Shiue I, Shore HR, Shrime MG, So S, Soneji S, Stathopoulou V, Stroumpoulis K, Sufiyan MB, Sykes BL, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tadese F, Tedla BA, Tessema GA, Thakur JS, Tran BX, Ukwaja KN, Uzochukwu BSC, Vlassov VV, Weiderpass E, Wubshet Terefe M, Yebyo HG, Yimam HH, Yonemoto N, Younis MZ, Yu C, Zaidi Z, Zaki MES, Zenebe ZM, Murray CJL, Naghavi M. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-years for 32 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145–164. doi: 10.3322/caac.21601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyngstrom JR, Hu CY, Xing Y, You YN, Feig BW, Skibber JM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Cormier JN, Chang GJ. Clinicopathology and outcomes for mucinous and signet ring colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2814–2821. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inamura K, Yamauchi M, Nishihara R, Kim SA, Mima K, Sukawa Y, Li T, Yasunari M, Zhang X, Wu K, Meyerhardt JA, Fuchs CS, Harris CC, Qian ZR, Ogino S. Prognostic significance and molecular features of signet-ring cell and mucinous components in colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1226–1235. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4159-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hugen N, van de Velde CJH, de Wilt JHW, Nagtegaal ID. Metastatic pattern in colorectal cancer is strongly influenced by histological subtype. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:651–657. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagante F, Spolverato G, Beal E, Merath K, Chen Q, Akgül O, Anders RA, Pawlik TM. Impact of histological subtype on the prognosis of patients undergoing surgery for colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:1355–1363. doi: 10.1002/jso.25044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu MZ, Pan WT, Lin JZ, Wang ZX, Pan ZZ, Wang FH, Yang DJ, Xu RH. Comparison of survival between right-sided and left-sided colon cancer in different situations. Cancer Med. 2018;7:1141–1150. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X, Lin H, Li S. Prognoses of different pathological subtypes of colorectal cancer at different stages: A population-based retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:164. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-1083-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hugen N, Verhoeven RH, Lemmens VE, van Aart CJ, Elferink MA, Radema SA, Nagtegaal ID, de Wilt JH. Colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy but a poor prognostic factor. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:333–339. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sargent DJ, Greene FL, Stewart AK. Revised TN categorization for colon cancer based on national survival outcomes data. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:264–271. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iasonos A, Schrag D, Raj GV, Panageas KS. How to build and interpret a nomogram for cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1364–1370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SY, Yoon MJ, Park YI, Kim MJ, Nam BH, Park SR. Nomograms predicting survival of patients with unresectable or metastatic gastric cancer who receive combination cytotoxic chemotherapy as first-line treatment. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s10120-017-0756-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu C, Chen YP, Liu X, Tang LL, Chen L, Mao YP, Zhang Y, Guo R, Zhou GQ, Li WF, Lin AH, Sun Y, Ma J. Socioeconomic factors and survival in patients with non-metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:1253–1262. doi: 10.1111/cas.13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge H, Yan Y, Xie M, Guo L, Tang D. Construction of a nomogram to predict overall survival for patients with M1 stage of colorectal cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2019;72:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Z, Mo S, Dai W, Xiang W, Han L, Li Q, Wang R, Liu L, Zhang L, Cai S, Cai G. Prognostic nomograms for predicting cause-specific survival and overall survival of stage I-III colon cancer patients: a large population-based study. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:355. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-1079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang ZY, Gao W, Luo QF, Yin XW, Basnet S, Dai ZL, Ge HY. A nomogram improves AJCC stages for colorectal cancers by introducing CEA, modified lymph node ratio and negative lymph node count. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39028. doi: 10.1038/srep39028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong X, Li J, Cai Y, Tian Y, Chi S, Tong D, Hu Y, Yang Q, Poston G, Yuan Y, Ding K. A modified TNM staging system for non-metastatic colorectal cancer based on nomogram analysis of SEER database. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:50. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3796-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan Q, Zhang K, Guo K, Liu S, Wasan HS, Jin H, Yuan L, Feng G, Shen F, Shen M, Ma S, Ruan S. Value of tumor size as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer patients after chemotherapy: a population-based study. Future Oncol. 2019;15:1745–1758. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato T, Alonso S, Muto Y, Perucho M, Rikiyama T. Tumor size is an independent risk predictor for metachronous colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:17896–17904. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai W, Li Y, Meng X, Cai S, Li Q, Cai G. Does tumor size have its prognostic role in colorectal cancer? Int J Surg. 2017;45:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghiasloo M, Kahya H, Van Langenhove S, Grammens J, Vierstraete M, Berardi G, Troisi RI, Ceelen W. Effect of treatment sequence on survival in stage IV rectal cancer with synchronous and potentially resectable liver metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:415–422. doi: 10.1002/jso.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghiasloo M, Pavlenko D, Verhaeghe M, Van Langenhove Z, Uyttebroek O, Berardi G, Troisi RI, Ceelen W. Surgical treatment of stage IV colorectal cancer with synchronous liver metastases: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:1203–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmed M. Colon Cancer: A Clinician's Perspective in 2019. Gastroenterology Res. 2020;13:1–10. doi: 10.14740/gr1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Cao W, Zheng C, Hu W, Liu C. Marital status and survival in patients with rectal cancer: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;54:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukund K, Syulyukina N, Ramamoorthy S, Subramaniam S. Right and left-sided colon cancers - specificity of molecular mechanisms in tumorigenesis and progression. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:317. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06784-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard JY, Peeters M, Lenz HJ, Venook A, Heinemann V, Van Cutsem E, Pignon JP, Tabernero J, Cervantes A, Ciardiello F. Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1713–1729. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, Tabernero J, Van Cutsem E, Beier F, Esser R, Lenz HJ, Heinemann V. Prognostic and Predictive Relevance of Primary Tumor Location in Patients With RAS Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Retrospective Analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 Trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:194–201. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loupakis F, Yang D, Yau L, Feng S, Cremolini C, Zhang W, Maus MK, Antoniotti C, Langer C, Scherer SJ, Müller T, Hurwitz HI, Saltz L, Falcone A, Lenz HJ. Primary tumor location as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Feng Y, Dai W, Li Q, Cai S, Peng J. Prognostic Effect of Tumor Sidedness in Colorectal Cancer: A SEER-Based Analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18:e104–e116. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]