Abstract

Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO) is an inflammatory bone disorder that most frequently affects children and adolescents. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) is a severe form of CNO, usually characterized by symmetrical inflammatory bone lesions and its waxing and waning character. Sometimes severe and chronic pain can significantly affect the quality of life and psychosocial development of individuals affected. In the absence of prospectively tested and widely accepted diagnostic criteria or disease biomarkers, CNO remains a diagnosis of exclusion, and infections, malignancy and other differentials require consideration (1). The pathophysiology of CNO is not fully understood, but imbalanced cytokine expression and increased inflammasome activation in monocytes from CNO patients contribute to a pro-inflammatory phenotype that contributes to bone inflammation (2). Currently, no medications are licensed for the use in CNO. Most patients show at least some response to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, others require more aggressive treatment that can include corticosteroids, cytokine-blocking agents and/or bisphosphonates (3). While under the care of an experienced team and sufficient treatment, the prognosis is good, but some patients will develop sequalae which can include vertebral compression fractures (1).

Keywords: Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis, CNO, Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, CRMO, Treatment, Pathophysiology

Highlights

-

•

CNO is an autoinflammatory bone disorder mostly affecting children and adolescents.

-

•

Dysregulated cytokine expression and pathological activation of inflammasomes play a central role.

-

•

Treatment is based on experience from case series and expert consensus treatment plans.

-

•

Understanding the exact molecular pathophysiology will allow patient stratification and individualized treatment.

1. Introduction

Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO) is an autoinflammatory bone disease that most commonly affects children and adolescents. While previously considered a rather mild and self-limiting condition, based on chronic and severe pain as well as possible complications (including vertebral body fractures) CNO is now considered a severe and in some cases devastating condition. Indeed, CNO covers a clinical spectrum with sometimes mild and self-limited monofocal lesions at one end, and chronically active or recurrent multifocal disease at the other end. In the letter, the term chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) is used [1].

Other names have been used for CNO which include SAPHO (Synovitis, Acne, Pustulosis, Hyperostosis, and Osteomyelitis) or nonbacterial osteomyelitis (NBO) and may represent the same disease entity. Adult rheumatologists frequently use the acronym SAPHO talking about CNO. Technically, however, SAPHO should only be used for patients with cutaneous features, including acne and pustulosis [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]].

In light of the aforementioned, CNO is a heterogeneous disorder and not all symptoms may occur at the same time which can make diagnosis challenging. On the other hand, as the awareness of CNO is rising, misdiagnosis can occur when alternative diagnoses are not intentionally sought. In the following sections clinical and laboratory features, the molecular pathophysiology and treatment of CNO will be discussed.

2. Epidemiology

Though the incidence of CNO has been reported as low as 4 per million children [6], increasing cases have been seen in multiple centers as awareness is raised [7,8]. In a tertiary center in the UK, after a letter was sent to referring orthopedic physicians, increasing numbers of CNO patients were referred to the pediatric rheumatology team [8]. Indeed, incidences of bacterial osteomyelitis and CNO in a tertiary center in Germany were comparable over a 10-year span [7]. In line with this, national surveillance data from Germany delivered comparable numbers of cases with bacterial osteomyelitis (n=378) and those with CNO (n=279) over a 5-year period [9]. As CNO patients are initially seen by variable specialties, close collaboration between pediatricians, rheumatologists, orthopedists, infectious disease specialists, oral surgeons, oncologists, radiologists and others is crucial to diagnose and treat patients early before the development of complications or the initiation of unnecessary and/or ineffective treatment (e.g. cytotoxic drugs for suspected malignancies, or antibiotics for suspected infections, etc.). Once diagnosed, CNO patients are primarily treated and followed up by pediatric rheumatologists.

Overall, girls and young women appear to be more frequently affected (approximately 2:1), and most patients develop symptoms between 7 and 9 years-of-age. Of note, stand-alone CNO is rarely seen in children younger than 3 years of age. In this age group, differential diagnoses, including systemic autoinflammatory disease with bone involvement needs to be considered carefully. While White Caucasians are the most frequently reported race in literature, all ethnicities can be affected [7,[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. Due to sometimes mild and unspecific clinical presentations in some children, the diagnosis can be delayed; a survey in the USA unveiled an average delay of approximately 2 years [16].

3. Clinical features

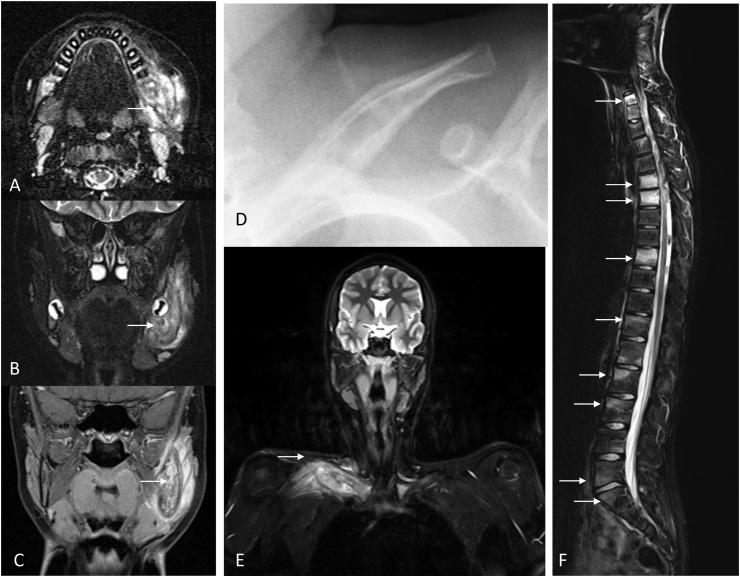

Clinical features in CNO are not disease specific. Most patients with CNO experience insidious chronic bone pain that affects patients’ quality of live and school attendance. Children with CNO generally appear well, but fatigue and delayed growth may occur in some. Nocturnal bone pain is reported by a subset of patients and may be interpreted as “growing pain” or primary non-malignant bone tumor (namely osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma). Physical exams are frequently normal, but focal tenderness and/or warmth may be present [17]. Sometimes, regional swelling over bones with little overlying soft tissue may be palpable, such as over the mandible (Fig. 1A–C), clavicle (Fig. 1D and E), hand bones, foot bones or distal tibia/fibula. In the authors’ experience, children with pubic bone lesions and associated pain may present with constipation and/or enuresis (unpublished data).

Fig. 1.

Typical bone involvement in CNO. A-C) MRI images from a 13-year-old girl with CNO and Crohn’s disease showing hyperintense signal alterations in a thickened left mandible with bone destruction (TIRM: A, B), and contrast enhancement (T1 with fat saturation, C). D) Conventional X-ray showing a clavicular CNO lesion with bone thickening and periostal reaction. E) MRI (TIRM) showing hyperintense signal alterations in a thickened and destroyed left clavicle of a 15-year-old CNO patient. F) MRI (TIRM) showing hyperintense lesions in multiple vertebral bodies of a 13-year-old CNO patient.

Pain is the most prominent and frequent feature in CNO. While acute onset of pain may occur and result in a swift diagnostic workup and timely interventions, waxing and waning complaints are typical in CNO [7,[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. Clinically silent bone lesions can occur and may affect vertebral bodies [18] (Fig. 1F). Unfortunately, data are lacking on functional assessment and effects of pain in CNO. A prospective cohort study reported improvement of function with treatment of CNO, measured by the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ) score over a 12-month period [19]. However, even after remission is achieved, physical and school function measured by PedsQL are found to be reduced in CNO patients when compared to matched healthy controls [20].

Systemic features, such as fever, night sweats and/or weight loss may occur in up to 17% of children and may raise concerns about alternative diagnoses [12].

Distribution of lesions have been extensively studied (usually using WB-MRI, see below) at presentation and throughout the disease course [7,[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15],21], and usually affect metaphyses of long bones, especially within lower extremities near knees, and ankles. Symmetrical lesions can be seen in 20 of 89 cases (22%) and was considered as a criterion by Jansson et al. [18]. Vertebrae, mandible, clavicle and pelvis including os sacrum, os ilium, the periacetabulum, os ischium and os pubis are considered classic sites in CNO. Indeed, a subset of patients develops a clinical picture in-line with spondylitis, and even fulfill European Spondylitis Study Group (ESSG) criteria [22,23]. Involvement of the sternum has been reported mostly in SAPHO but is less common in children [4,[24], [25], [26]].

The number of lesions at initial onset may be underestimated due to the lack of universal acquisition of whole-body MRI (WBMRI), which is considered the gold standard imaging modality for this disease. Only 30% of patients had whole body imaging at initial diagnosis as reported by the two largest cohort studies [10,11]. When WBMRI imaging was used exclusively at initial diagnosis, 52 out of 53 children (98%) had 2 or more lesions [21]. If unifocal lesions were present, clavicle and mandible were most likely to be affected [11,27].

The waxing and waning feature of CNO and cyclic course necessitates long-term data collection to identify patterns of disease and response to treatment. The reported recurrence rate of this disease varies dramatically, from 16% during the first year in children treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to 83% in children at later time points [12,[28], [29], [30]]. Despite treatment with pamidronate, 4 out of 9 patients (44%) experienced at least one disease flare as confirmed by MRI [30]. Furthermore, the low recurrence rate (19%) within another cohort (n=41) was due to the high rate of persistent disease (66%) [29]. Nine patients (22%) required NSAIDs monotherapy or combination with second-line treatment for longer than 5 years with the longest course of 13 years [30] underscoring the chronic nature of CNO.

Other organs may be affected. Cutaneous diseases, such as severe acne, psoriasis, palmoplantar pustulosis, Sweet syndrome and/or pyoderma are present in 4–20% of patients [10,11]. Psoriasis and pustulosis may occur after treatment initiation [31]. An association with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been reported, which is likely under-reported and may explain arthralgia and bone pain in a subset of IBD patients [7,16,32].

4. Diagnostic approach

4.1. Laboratory studies

Routine laboratory tests deliver unspecific results, but can help to exclude differential diagnoses (see below). Usually, mildly elevated CRP and ESR are present, with frequencies ranging from 49 to 80% in large cohorts [10,11,18]. Although not specific and not excluding CNO, highly elevated CRP, ESR (>3x of normal upper limit) in a suspected case should warrant further investigation for alternative causes [16]. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA; 8–38%) and HLA-B27 (2–25%) are found to be positive in a subset of children with CNO [7,10,11,14,18,[27], [28], [29]].

Elevated serum cytokines and/or chemokines may be useful tools to diagnose CNO patients in the future. Serum TNF-alpha and IL-6 levels are mildly elevated in a proportion of CNO patients [18,33]. Recently, a set of serum proteins (namely the cytokine IL-6, the chemokines CCL11/eotaxin and CCL5/RANTES, collagen Iα, and the soluble IL-2 receptor/sIL-2R) have been reported to be elevated in CNO patients [34,35], some of which may help to differentiate between CNO and differential diagnoses such as infection or malignancy [34]. Three serum proteins promise potential for the assessment of disease activity in response to treatment, namely the chemokine MCP-1, the cytokine IL-12, and the soluble IL-2 receptor [35]. However, findings are preliminary and require confirmation in unrelated multi-ethnic cohorts and with additional assays.

Key laboratory markers of differential diagnoses such as LDH and uric acid (malignancies), alkaline phosphatase (hypophosphatasia) and vitamin C (scurvy) are useful to measure at least initially and remain normal in CNO. Due to lack of specific disease markers, no laboratory tests, including ESR, are reliable to monitor disease activity.

Urine N-telopeptide has been suggested to be of value for detecting flares in CNO patients treated with bisphosphonate [30]. However, findings have not been validated in additional studies.

4.2. Imaging studies

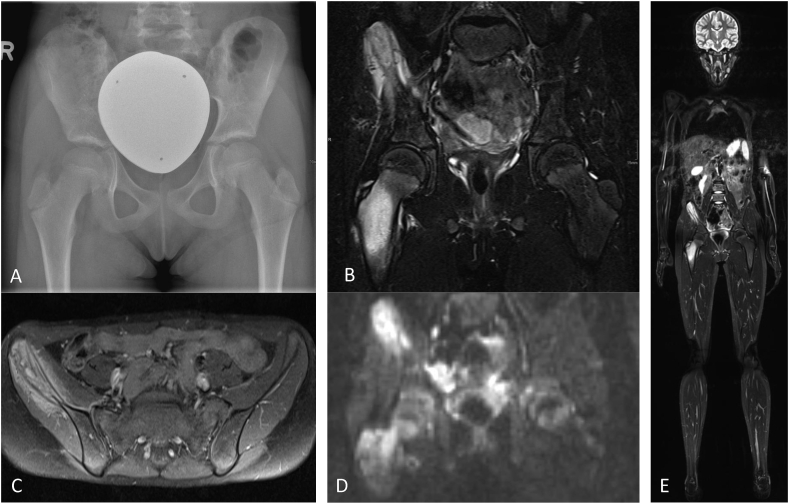

Classic radiographs are frequently used for initial screening and to exclude fractures. Findings seen on plain films in some CNO patients include lytic bone lesions, sclerosis and hyperostosis. Of note, their absence does not necessarily exclude CNO [36] (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Suggested imaging approach in CNO at diagnosis. A) regional X-ray showing minimal sclerosis of the right ilium, B) MRI (TIRM sequences) showing hyperintense signal in os ilium and proximal femur with reaction of surrounding tissue, C) MRI (T1 with contrast) showing contrast enhancement of thickened os ilium with bone destruction and perifocal soft tissue reaction D) MRI (diffusion weighted images; DWI) showing restricted diffusion in os ilium and proximal femur, E) Whole-body MRI showing multifocal skeletal hyperintense lesions (TIRM).

Historically, bone scintigraphy was used to diagnose CNO, to screen for clinically silent lesions (especially affecting vertebral bodies) and to monitor disease activity. However, based on associated radiation and the availability of alternative and more sensitive alternatives (namely whole-body magnetic resonance imaging, WB-MRI, see below), this strategy is obsolete in children and young people and should only be used if absolutely necessary (e.g. if WB-MRI imaging or serial MRIs covering sections of the body are not available).

While computed tomography (CT) should generally not be used in children with suspected CNO secondary to associated radiation and aforementioned benefits of MRI, it may be useful for some colleagues in relatively rare circumstances, e.g. osteoid osteoma when there’s remaining uncertainty after MRI imaging [27].

Today, MRI is the preferred imaging tool to diagnose and monitor CNO (Fig. 2B–E). At the time of diagnosis MRI strategies usually include regional imaging using TIRM (or STIR) sequences to localize and assess the extent of inflammation, followed by native T1 sequences and contrast enhanced T1 weighted sequences with fat saturation to assess regional changes. Importantly, and other than alternative bone imaging modalities (radiographs, CT or scintigraphy), MRI allows for the assessment of structures surrounding bones and the extent of tissue inflammation. Furthermore, MRI has higher sensitivity when compared to bone scintigraphy, CT or radiographs as it detects edema as a sign of inflammation and is not depending on the development of bone remodeling and/or structural damage [36]. Lastly, MRI spares children from radiation.

Whole-body MRI provides information on the distribution of lesions, soft tissue involvement and/or possible involvement of additional organs which can be present in differential diagnoses, such as malignant disease (e.g. neuroblastoma). Thus, WB-MRI is a key tool to exclude differential diagnoses. At the time of diagnosis, and when indicated during disease course, WB-MRI should be performed to screen for clinically silent lesions, especially vertebral lesions which may result in compression fractures. Usually, WB-MRI techniques include fluid-sensitive sequences (STIR/TIRM, or sometimes regular T2 with fat saturation) which allow for optimal visualization of inflammation (edema) of the skeletal system and adjacent tissue [32,37].

To harmonize imaging techniques used and assessment of results, scoring of CNO lesions has been proposed by different groups and include bone and soft tissue inflammation (fluid resulting in hyperintensity on T2/STIR/TIRM) and associated bone destruction, periosteal reaction, hyperostosis (bony expansion), growth plate damage and vertebral compression [[37], [38], [39]]. One study demonstrated that bone marrow scores across lesions and total numbers of non-vertebral lesions significantly decreased in response to rather aggressive treatment with methotrexate, infliximab and/or zolendronic acid, while soft tissue inflammation scores improved in response to NSAIDs [39].

Another study suggested classification of CNO into sub-groups based on the distribution of bone lesions following two main patterns [38]. The “tibio-appendicular multi-focal pattern” with the presence of tibial lesions (66% had symmetrical tibial lesions), was the predominant cluster (54%) followed by the “claviculo-spinal pauci-focal pattern” with the presence of clavicular lesions (24%), in the presence or absence of lesions in the spine. However, currently this remains purely descriptive and it remains to be determined whether these patterns may be used to predict outcomes and/or guide the treatment.

4.3. Bone biopsies

Based on the literature available, bone biopsies are performed in 60–80% of patients with CNO [7,8,18,29]. While no disease specific patterns have been reported in bone biopsies from patients with CNO, they can exclude differential diagnoses, such as infections, fibrous dysplasia, malignancy or Langerhans cell histiocytosis [40]. Findings in bone biopsies from CNO patients include dense infiltrates of immune cells, lysis of bone, fibrosis and/or normal bone [1,18]. Indeed, cellular infiltrates can change over time with mainly innate immune cells in early disease stages, including neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages, and lymphocytes including plasma cells during later disease stages. Macrophages appear to be the most stable cellular component during these phases [41]. However, innate and adaptive infiltrates can frequently co-exist and may reflect the waxing and waning character of CNO with phases of disease activity and remission [41].

Lastly, in individual cases, Propionibacterium/Cutibacterium acnes may be detected in bone biopsies, which complicates the diagnosis [40,42]. Usually, Propionibacteriae have been discussed as contaminant. As such, and as environmental triggers to CNO have been proposed, skin colonization e.g. with Cutibacterium acnes may trigger bone inflammation through Toll-like receptor signaling in predisposed individuals. However, this has not been proven experimentally yet. The presence of Cutibacterium acnes in a subset of bone biopsies causes a clinical dilemma as acute or chronic bacterial osteomyelitis may not cause significant elevation of systemic inflammatory parameters, especially when low virulent strains of bacteria are present [43,44].

4.4. Diagnostic criteria

Currently, CNO remains a diagnosis of exclusion as no widely accepted and prospectively tested diagnostic criteria are available.

Three individual groups suggested diagnostic criteria for CNO [8,18,45] which all include overall stable or good clinical appearance of patients, disease duration of 6 months or more, the presence of multifocal bone lesions with “typical” appearance on imaging (in which biopsies are not always necessary) or unifocal lesion with no evidence of infection and malignancy. None of these criteria has been validated prospectively, and the identification of “typical” lesions on MRI may be largely dependent on a center’s experience with the condition. Furthermore, a number of differential diagnoses may be associated with symmetrical bone lesions on MRI, including lymphoma, scurvy (Box 1), Langerhans cell histiocytosis or hypopthosphatasia.

Box 1.

A 7-year-old boy with severe autism developed progressive pain of arms and legs over a 4-month period. This was preceded and coincided with increasingly difficult eating habits and loss of 10% body weight. The patient developed progressive follicular keratosis, micro-bleeds of the skin (A), and gingivitis (B). Whole body STIR-MRI sequences showed symmetric signal alterations over methaphyses and epiphyses of long bones and feet (C). Blood cell counts and systemic inflammation parameters (CRP and ESR) were normal, bone marrow was hypo-cellular. Bone biopsy unveiled chronic inflammation with cellular infiltrates of neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes, and areas with bone fibrosis. The patient was referred to Paediatric Rheumatology for suspected chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO), an autoinflammatory bone condition.

Based on the patient’s history and aforementioned clinical findings (feeding difficulties, gingivitis, dermatosis and osteitis) as well as evidence of ascorbic acid deficiency in the patient’s serum (<1 μmol/L), the diagnosis of scurvy was made. In response to vitamin C supplementation, pain resolved within days, gingivitis and skin changes normalized within 4 weeks.

This case highlights that vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) should be considered in patients with chronic pain and/or aseptic osteitis, particularly where there are feeding difficulties associated with conditions such as autism and/or developmental delay.

MRI images with parental consent and friendly permission from Dr Caren Landes, Radiology Department, Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust Hospital.

Alt-text: Box 1

4.5. Differential diagnoses

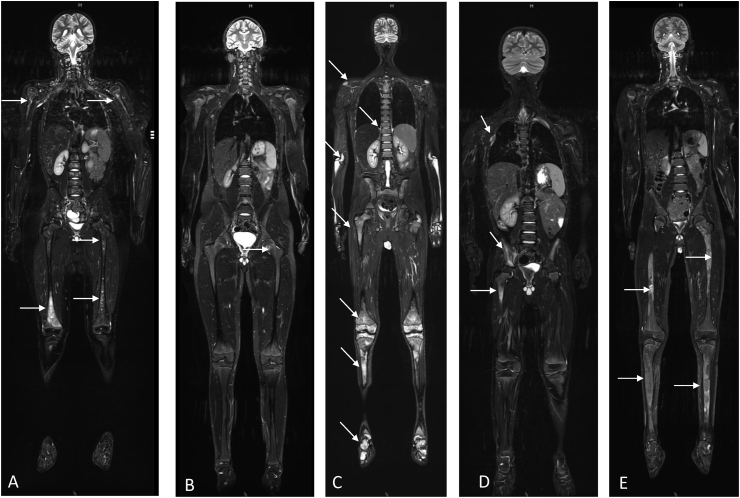

A number of other conditions may result in bone pain and radiographic anomalies that may be suggestive of CNO (Fig. 3). As diagnostic criteria do not exist for CNO, these differential diagnoses require consideration and exclusion in the context of an individual patient’s clinical presentation, age and history. A (likely incomplete) list of differential diagnoses is provided in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Whole-body MRI scans of patients with differential diagnoses to CNO (coronal TIRM sequences). A) Skeletal metastases of neuroblastoma with multiple small and large areas of hyperintense signal alterations (arrows). B) Mycobacteriosis in interferon gamma receptor (IFNGR) defect with small hyperintense areas and central hypointensity (arrow). C) Primary bone lymphoma with inhomogenous hyperintense lesions of the entire skeleton. D) Langerhans cell histiocytosis with hyperintense lesions in proximal femur, right os ilium and third right rib (arrows). E) Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia with inhomogenous hyperintense tibiae and femora (arrows).

Table 1.

Differential diagnoses to CNO (may be incomplete).

| Disease (group) | Examples |

|---|---|

| Bone tumors | Malignancies, including:

|

| Hematological malignancies | Leukemia, lymphoma (Fig. 3C) |

| Metabolic disease | Hypophosphatasia |

| Bone infection | Bacterial osteomyelitis |

| Primary immune deficiency | Defects of IFN-gamma/IL-12 axis (favoring mycobacterial infections) (Fig. 3B) |

| Vitamin deficiency | Scurvy/vitamin C deficiency (box 1) |

| Other autoinflammatory diseases with bone involvement |

|

| Others |

5. The pathophysiology of CNO/CRMO

Over the past years scientific efforts improved our understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of CNO/CRMO. However, because of the complexity of mechanisms involved, and the clinical and molecular variability between patients, the exact pathophysiology of CNO/CRMO still remains unknown.

5.1. Cytokine dysregulation and osteoclast activation

In the absence of disease-causing infections and following their definition (of systemic or organ-specific inflammatory conditions that are at least initially caused by uncontrolled activation of the innate immune system in the absence of autoreactive lymphocytes and high-titer antibodies), CNO/CRMO is classified as an autoinflammatory condition [1,46].

Though considered in early publications and presentations from primarily surgical specialties, infectious causes of CNO/CRMO have been excluded by several studies [40]. Furthermore, antibiotic treatment fails to induce sustained remission in CNO/CRMO patients [18,40,[47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55]]. Initial reports on Propionibacterium acnes, Mycoplasma spp., or Staphylococcus spp. in bone biopsies were likely due to contamination with skin commensals [22,40,48,49,53,[55], [56], [57], [58]]. However, since certain bacteria alter immune responses, the question of whether pathogens may “indirectly” contribute to disease expression can be raised, but currently remains unanswered (see also below: “The microbiome in CNO/CRMO”).

Over recent years it became clear that altered cytokine and chemokine expression in innate immune cells is involved in the pathophysiology of CNO/CRMO. Monocytes from CNO/CRMO patients express reduced levels of the immune regulatory cytokine IL-10 and its homolog IL-19 while expressing increased amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and chemokines (IL-8, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1a, MIP-1b) [33,35,59,60]. Reduced expression of IL-10 and IL-19 is (at least partially) caused by impaired activation of mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK)-1 and 2. This, in turn, results in reduced phosphorylation of the transcription regulatory factor signaling protein-1 (Sp-1). Sp-1 plays a key role in the expression of IL-10 and IL-19, and impaired recruitment of Sp-1 to regulatory elements within the IL10 and the IL19 promoters contributes to reduced gene expression [33,60]. Furthermore, ERK1/2 are involved in the phosphorylation of histone proteins. Histones aggregate in octamers that associate with DNA to so-called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes contribute to the regulation of DNA accessibility, a key mechanisms to control gene transcription. Reduced activation of ERK1/2 in CNO/CRMO results in altered histone H3 serine 10 (H3S10) phosphorylation at the IL10 promotor [33,[60], [61], [62]]. Reduced H3S10 phosphorylation in CNO/CRMO in turn contributes to further reduced Sp-1 recruitment to IL10 [33,59,60] and subsequently altered gene expression.

Another recent observation in immune cells from patients with CNO/CRMO is increased NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a cytoplasmic multi-protein complex that assembles in response to “danger signals”. Subsequently, NRLP3 inflammasome assembly results in the activation of pro-inflammatory caspase-1 which cleaves biologically inactive pro-IL-1β and releases highly pro-inflammatory active IL-1β [41,59]. Scianaro et al. [63] reported increased expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components (ASC, NLRP3, caspase-1) and increased IL-1β mRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from CNO/CRMO patients. Furthermore, Hofmann et al. reported associations between reduced expression of IL-10 and IL-19 and increased IL-1β mRNA expression and protein release in monocytes from CNO/CRMO patients [59]. This is of particular interest, since in IL-10-deficient animals, increased inflammasome assembly and IL-1β release was also linked with inflammatory bone loss [64]. Tightly controlled expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines regulate osteoclast differentiation and activation through interactions between receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK) on osteoclast precursor cells and its ligand (RANKL) [[65], [66], [67], [68]]. Thus, imbalanced expression and release of cytokines in CNO/CRMO may be central to its molecular pathogenesis.

5.2. Genetic factors in the pathophysiology of CNO/CRMO in humans

Several lines of evidence suggest the involvement of genetic factors contributing to CNO/CRMO in humans and animals: i) Familial clusters of CNO/CRMO affecting siblings or patients from several generations within one family; ii) approximately 50% of individuals with CNO have a personal or family history of other autoimmune/inflammatory conditions, including psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease and/or inflammatory arthritis [6,7,18,[69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74]]; iii) a number of animals develop CNO/CRMO or CNO/CRMO-like disease that may share common mechanisms with human disease [[75], [76], [77], [78]]. Based on these observations, genetic analyses were performed and delivered syndromic forms of human CNO/CRMO and murine models that highlighted susceptibility genes for sterile osteomyelitis.

Majeed syndrome is a severe familial form of CNO/CRMO, presenting with early-onset sterile bone inflammation, and dyserythropoietic anemia with or without a neutrophilic dermatosis [79]. It follows autosomal recessive inheritance and has been linked to homozygous mutations in the LPIN2 gene [80,81]. Basic studies and response to IL-1 blocking treatment confirmed a central involvement of pro-inflammatory IL-1β in the pathophysiology of Majeed syndrome and resulted in its classification as a NLRP3 inflammasome-associated condition (“Inflammasomopathy”) [82,83]. As mentioned above, the NLRP3 inflammasome is a cytoplasmic complex that assembles in response to “danger signals”. Its assembly results in the activation of pro-inflammatory caspase-1 which cleaves biologically inactive pro-IL-1β into its active from. Deficiency or reduced expression of LIPIN2 results in reduced intracellular cholesterol and aberrant function of the P2X7 receptor in macrophages. This results in increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the release of IL-1β. Of note, altered P2X7 function and increased inflammasome activation can be reversed by cholesterol [83]. Treatment of a small cohort of patients with Majeed syndrome with IL-1 blocking agents underscores the importance of IL-1β in the pathophysiology of Majeed syndrome [82,84,85]. Both bone inflammation and anemia improved in response to IL-1β blockade. However, it is currently unknown whether resolved anemia is the result of controlled systemic inflammation or resolved dyserythropoiesis. This would have to be confirmed through prospectively collected bone marrow biopsies, which aredifficult to justify in the context of good clinical response to treatment.

Deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist (DIRA) is another early-onset systemic inflammatory disease characterized by multifocal sterile osteitis, periostitis and pustulosis [86,87]. In DIRA, autosomal recessive loss-of-function mutations in IL1RN (homozygous truncations, deletions and compound heterozygous mutations) result in deficiency/absence of the endogenous post-transcriptional regulator IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) which subsequently results in uninhibited pro-inflammatory IL-1 signaling [86]. Secondary to resulting severe systemic inflammation, untreated DIRA is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. However, recognition of DIRA as a distinct syndromic entity (with clinical symptoms of early-onset osteitis, periostitis and pustulosis) allows timely diagnosis based on the clinical picture in conjunction with DNA sequencing. Effective and target-directed treatment of DIRA is available through substitution of recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist [86,87].

However, most individuals with CNO/CRMO do not experience monogenic disease. In these cases, genetic predisposition (as opposed to monogenic inheritance) is involved in the pathophysiology, but not strong enough to cause disease in the absence of additional factors. Several studies have investigated genetic associations in CNO/CRMO cohorts:

-

i)

Because of overlapping features between “sporadic”/non-familial CNO/CRMO and the aforementioned monogenic disorder DIRA, the IL1RN gene was sequenced in a CNO/CRMO patient cohort, but no CNO-associated mutations were identified [88].

-

ii)

Expression of the immune-regulatory cytokine IL-10 is reduced in monocytes from patients with CNO/CRMO (see below). IL-10 expression is determined by a series of three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs1800896 (−1082A > G), rs1800871 (−819T > C), and rs1800872 (−592A > C) that together form promoter haplotypes (GCC, ACC, and ATA) thereby influencing transcription factor binding [89,90]. Unexpectedly, considering reduced IL-10 expression in monocytes from CNO/CRMO patients, increased frequencies of IL10 promoter haplotypes that encode for “high” IL-10 expression (GCC) were observed in a cohort of 100 CNO/CRMO patients [90,91]. While currently hypothetical, enrichment of GCC haplotypes in the studied CNO cohort may be explained by individuals with CNO-associated molecular disturbances and IL10 promoter haplotypes encoding for “low” IL-10 expression developing more severe disease that includes CNO as a symptom among others. Such combinations may result in phenotypes that may not be identified as CNO/CRMO (e.g. IBD with CNO, etc.) [33,92]. However, this explanation currently remains speculation.

-

iii)

Using whole exome sequencing, a CNO/CRMO susceptibility gene was recently identified in two unrelated CNO patients from South Asia. One patient carried a homozygous mutation, the other patient a compound heterozygous mutation in the filamin-binding domain of the FBLIM1 gene [93,94] encoding for the Filamin-Binding LIM Protein-1 (FBLP-1). Though incompletely understood, FBLIM1 is important in bone remodeling and involved in cytoskeletal regulation [15]. FBLIM1-deficiency in mice results in increased osteoclast activation and severe osteopenia [95]. This has been linked to FBLIM1 acting as an anti-inflammatory molecule controlling bone remodeling through the regulation of RANKL activation through ERK1/2 phosphorylation [93,94]. This suggests that FBLIM1 mutations may cause disruptions in signaling pathways previously identified in (European) CNO/CRMO patients [33,60]. This is further supported by the observation that FBLIM1 expression is dysregulated in bone marrow-derived macrophages from osteitis-prone Pstpip2 mice (see below) [93,94]. Trans-activation of the FBLIM1 gene is regulated by the transcription factor Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT)3 [93,94]. The aforementioned immune-regulatory cytokine IL-10 (that fails to be expressed in monocytes from CNO/CRMO patients) induces STAT3 phosphorylation/activation. Indeed, CNO/CRMO patients with mutations in FBLIM1 exhibit IL10 promoter haplotypes that code for “low” IL-10 expression, which may result in reduced STAT3 activation and down-stream effects on FBLIM1 expression [94].

-

iv)

The most recent addition to genetic susceptibility for CNO/CRMO in humans comes from a murine model of sterile multifocal osteomyelitis. The Ali18 mouse exhibits a gain-of-function mutation in the feline Gardner-Rasheed sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (Fgr), a member of the Src kinase family [96]. Ali18 mice develop aseptic inflammation of bones, skin and joints [[97], [98], [99]]. Whole exome sequencing of CNO/CRMO patients identified 13 patients with heterozygous missense variants within FGR, two of which alter kinase activity supporting a role for FGR in human CNO/CRMO [96].

5.3. CNO/CRMO in animals

Several animal species can develop CNO/CRMO or CNO/CRMO-like disorders, some of which serve as laboratory models for human disease. Hypertrophic osteodystrophy (HOD) is a canine disease that predominantly affects the Weimaraner breed. Animals affected develop multifocal sterile bone inflammation that, as in humans with CNO/CRMO, can be accompanied by skin (pustulosis) or inflammatory bowel disease [75]. While HOD clusters in litters, strongly supporting a genetic cause, the causative gene remains unknown.

Three available mouse strains with loss-of function mutations in the Pstpip2 gene that encodes for the proline-serine-threonine phosphatase-interacting protein 2, develop severe systemic inflammation and multifocal aseptic osteitis:

-

i)

Lupo mice were generated through induction of homozygous mutations (c.Y180C; p.I282 N) [100,101];

-

ii)

chronic multifocal osteomyelitis (cmo) mice spontaneously acquired homozygous mutations in Pstpip2 (c.T293C, p.L98P);

-

iii)

targeted knock-out of Pstpip2 exons 3 and 4 delivered a murine system resembling the clinical picture of SAPHO syndrome including skin disease [102].

The exact contribution of Pstpip2 to sterile osteomyelitis remains unclear [102]. PSTPIP2 is a member of the F-BAR (Fes/CIP4 homology-Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs) domain containing protein superfamily that links membrane remodeling with actin dynamics and filopodium formation [103]. Actin polymerization is increased in PSTPIP2-deficient macrophages which results in defective podosome formation and a more invasive phenotype [104]. As in human CNO/CRMO, pro-inflammatory IL-1β plays a pathophysiological role in cmo mice [105,106]. Indeed, animals deficient of the IL-1 receptor I (IL-1RI) or IL-1β do not develop aseptic osteomyelitis [105,106], while NLRP3, ASC or caspase-1 deficient mice develop disease. This suggests the involvement of alternative kinases or proteases (other than caspase-1) in the activation of IL-1β in cmo animals [107]. This is further supported by the observation that caspase-1 or caspase-8 deficient mice develop aseptic osteitis, while animals deficient of both are protected [108]. In addition to neutrophils and macrophages, mast cells play a role in aseptic osteitis in cmo mice. Mast cells are present in inflammatory bone lesions and mast cell protease I can be detected in the peripheral blood of cmo mice. In turn, mast cell-deficient animals exhibit attenuated disease suggesting their direct contribution or (at least) amplification of inflammation through mast cells. This is in line with the presence of mast cells and neutrophils in bone biopsies from children with CNO/CRMO and elevated levels of mast cell chymase in their peripheral blood [109].

It is, however, worth mentioning that although Pstpip2-deficient animals resemble severe CNO/CRMO, mutations in the human equivalent PSTPIP2 have not been found in CNO/CRMO patients. Indeed, mutations in cmo and lupo mice are located in a region of the Pstpip2 gene that is not present in humans.

5.4. The microbiome in CNO/CRMO

Since most humans with CNO/CRMO (likely) have genetic predispositions that are not strong enough to confer disease in the absence of additional factors, environmental impact on the immune system may play a role.

Along these lines, host interactions with the microbiome have been proposed to affect immune homeostasis and contribute to inflammatory disease onset [110]. Recently, studies in cmo mice and preliminary observations in humans with CNO/CRMO delivered support for this hypothesis. Lukens et al. [108] reported that dietary manipulation of the microbiome in osteomyelitis-prone cmo mice can prevent osteomyelitis. Zeus et al. recently reported alterations to the oral microbiome in CNO/CRMO patients in response to treatment with NSAIDs and the induction of clinical remission [111]. However, since a healthy control groups was not included, these findings do not convincingly prove a link between altered oral microbiomes and CNO/CRMO.

6. Treatment

6.1. Currently available treatment options

In the absence of published evidence from prospective trials, treatment of CNO/CRMO is largely empiric and based on personal experience, expert opinion, case reports and small case series. Consensus treatment plans have recently been published by the Childhood Arthritis & Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) with the aim to prospectively collect data on treatment responses [45].

In clinical practice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are usually used as first-line agents in patients without involvement of the vertebral column. NSAIDs provide relatively quick symptomatic relief [18,19,35,49,[112], [113], [114], [115]], and are effective in controlling bone inflammation in a subset of CNO/CRMO patients. However, over 50% of CNO/CRMO patients develop flares under NSAID treatment within 2 years from treatment initiation [7]. NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes and reduce inflammasome assembly to varying extents [116]. The observations that prostaglandins (which are depending on COX enzymes) are involved in osteoclast activation, and that increased inflammasome activation is increased in monocytes from CNO/CRMO patients are arguments for NSAID use in CNO/CRMO [68]. However, NSAIDs alone are considered not sufficiently effective in CNO/CRMO patients presenting with spinal involvement [19]. Thus, for these patients and individuals who failed to respond to NSAIDs, additional treatments are required.

Corticosteroids, disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs: sulfasalazine and methotrexate), biologic treatments (anti-TNF agents), and bisphosphonates have been reported to be effective in small cohorts of CNO/CRMO patients [1,35,55,68,73,92,117,118]:

Similar to NSAIDs, but through the inhibition of phospholipase A1, corticosteroids reduce prostaglandin production. Furthermore, corticosteroids negatively affect the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines regulated by the transcription factor NFκB, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α [68]. In clinical practice, short oral courses of 2 mg/kg/day prednisone equivalent can be administered over 5–10 days. Other colleagues prefer low-dose prednisone equivalent (0.1–0.2 mg/kg/day) as “bridging therapy” until concomitantly introduced DMARDs develop full efficacy. Corticosteroids quickly control bone inflammation in most cases (79%), but mostly fail to induce long-term remission [7]. Since a significant proportion of patients flare after discontinuation and corticosteroid-associated side effects can be challenging, long-term use should be avoided [68,112,113,115].

The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α is expressed at increased levels in monocytes from CNO/CRMO patients and elevated in their serum. Thus, TNF inhibitors have been used in the treatment of CNO/CRMO and induce clinical and radiological remission in a large proportion of patients. However, due to the off-label character and relatively high associated costs, cytokine blocking strategies should only be considered for cases refractory to other treatments [18,55,68,112,119,120].

Additional preliminary evidence for the efficacy of biological DMARDs in SAPHO exists and promises potential also for the use in “classical” CNO [45,121]. Preliminary reports suggest IL-1blockade with anakinra to have beneficial effects in osteitis and arthritis, but variable effects on mucocutaneous involvement [122,123]. Because of some clinical overlap between SAPHO and psoriasis treatment, the IL-17A neutralizing antibody secukinumab was successfully used in SAPHO patients [124]. Lastly, individual case reports suggest successful used of the PDE4-inhibitor apremilast and the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib in SAPHO [44,[125], [126], [127]].

Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast activity, thereby likely stopping inflammatory bone loss. Pamidronate furthermore has inhibitory effects on pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [68]. Indeed, pamidronate can induce rapid and long-lasting remission in most CNO patients [55,68,[128], [129], [130], [131]]. Two alternative treatment regimens have been reported and are commonly used in clinical practice: 1 mg/kg/dose (max. 60 mg/dose) every month, or 1 mg/kg/dose (max. 60 mg/dose) on 3 consecutive days every 3 months for 9–12 months. Zhao et al. reported rapid response to treatment with zoledronic acid in combination with the TNF inhibitor infliximab. While very promising and effective in a small cohort, the combination of zoledronic acid and infliximab does not allow an assessment of the exact contribution of each therapeutic [39]. Because of potential side-effects and the long biological half-life of bisphosphonates, they should only be considered in otherwise treatment refractory cases or in individuals with primary vertebral involvement and structural damage [55,68].

Data on other treatment options in CNO/CRMO is even more sparse. Treatment with classical non-biologic DMARDs (MTX, sulfasalazine) can be effective in some patients, but published case series report conflicting data [18,22,55,68,117,119]. Based on increased NLRP3 inflammasome assembly in monocytes from CNO/CRMO patients, IL-1 blocking strategies may be a promising therapeutic strategy. However, only few cases of anti-IL-1 treatment have been reported in CNO/CRMO and showed mixed response with variable outcomes [132]. Lastly, based on overlapping features between CNO/CRMO and psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and enthesitis-associated juvenile idiopathic arthritis, IL-17 blocking agents have been used anecdotally, but lack of published evidence currently prohibits their recommendation.

6.2. Potential future treatments

Recently reported observations from basic and early translational studies delivered a number of potential future treatment targets in CNO/CRMO. Altered activation of protein kinases [33,60] in CNO/CRMO patients may deliver arguments for future therapeutic targeting of these enzymes (e.g. Src kinase inhibition in patients with FGR mutations) [96]. The involvement of mast cells in bone inflammation may result in trials testing mast cell inhibitors in CNO/CRMO to control disease [109]. While studies available delivered individual proteins or pathways that are dysregulated in CNO/CRMO, therapeutic applications arising cannot be predicted with certainty.

Alterations to the murine microbiome alters disease outcomes in cmo mice [108] and human CNO/CRMO is associated with disorders that correlate with disturbed microbiomes (including acne, inflammatory bowel disease, etc.) [7]. Therefore, induced alterations to microbiomes may help to control CNO/CRMO or even prevent disease onset in genetically predisposed individuals [110]. Indeed, the potential involvement of altered microbiomes in CNO/CRMO may (at least partially) explain early reports suggesting that antibiotic treatment may be effective in individual CNO/CRMO patients (at least while administered) [47,48].

6.3. Discontinuation of treatment

The aforementioned absence of published evidence from clinical trials is only one challenge that can complicate patient care. Also, the required duration of treatment remains unknown. As CNO/CRMO is a chronic disease with phases or clinical activity and remission, prolonged treatment may be necessary [1,51,55,68,73,92,112,118,133]. Furthermore, decisions on introduction or escalation of treatment must be taken with caution, since i) signal alterations on MRI may be over-interpreted in asymptomatic patients, ii) lesions may resolve spontaneously without becoming clinically apparent or causing sequelae, and iii) therapeutic agents may cause side-effects and/or generate significant cost to health care systems. On the other hand, uncontrolled inflammation can result in increased morbidity, and vertebral involvement can result in fractures and complications associated with this [55,68,117].

The identification of easily accessible (e.g. serum or urine) biomarkers may help to facilitate diagnosis and allow monitoring of disease activity and treatment response. Indeed, serum IL-6 and CCL11/eotaxin may (likely in conjunction with other markers) be useful during the diagnostic workup, and IL-12, MCP-1, and sIL-2R may be useful markers for treatment response [34,35]. However, these preliminary results require confirmation in independent cohorts and prospective studies.

7. Outcome and prognosis

To date, large longitudinal studies prospectively investigating CNO patients from childhood to adulthood are lacking. However, retrospective cohort studies indicate that early and sufficient treatment and follow-up in a center experienced with the care of CNO patients is usually associated with favorable outcomes. Unfortunately, pre-existing damage, such as vertebral compression fractures, may not resolve in all cases [7,11,28,30,134,135].

In a small cohort study involving 17 patients with CNO, disease remained clinically active in 8 patients and radiographically active (MRI) in 13 patients after a median of 15 years [136]. However, some patients had been lost to follow-up intermittently, which may have resulted in over-estimation of the number of persistently active patients. Interestingly, even among CNO patients without clinical symptoms, bone edema was detected on MRI in almost half of the patients (4 of 9, including 2 patients with vertebral lesions). Though early reports suggest that CNO may be a self-limiting disease that disappears after 12–18 months in most cases, newer data indicate that, though most patients are in remission on treatment at 12 months, 50% of CNO patients develop disease flares after a median of 29 months [2,28]. These observations underscore the importance of long-term follow-up of CNO patients, including disease monitoring with MRI even in asymptomatic patients, but also raise the question of whether all of these radiographic lesions require treatment.

Complications in CNO may already be present at the time of diagnosis (e.g. vertebral fractures) or accumulate over time (arthritis, pustulosis, gastrointestinal inflammation). Data from a study in Germany suggest that, in some patients, symptoms of other autoimmune/inflammatory disorders may develop and reflect insufficient treatment, namely arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease [2,28]. Most common complications in CNO include vertebral compression fractures (which can be present in approximately 10% of CNO patients already at the time of diagnosis) [2,7,28,30,39,134,135], leg-length discrepancy, bony overgrowth (e.g. at the clavicle) and bone deformities [2,28]. Thus, in the authors’ institutions, active vertebral lesions on MRI trigger treatment initiation or escalation, while otherwise asymptomatic lesions may not be treated in all cases.

8. Conclusions

CNO is an autoinflammatory bone disorder characterized by pain, swelling, bone deformity, and, in some cases, pathological fracturs. While the pathophysiology is only incompletely understood, dysregulated cytokine expression and pathological activation of inflammasomes play a central role. Treatment is based on experience from case series and expert consensus treatment plans, and includes anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs, corticosteroids, DMARDs) and bisphosphonates. Additional research is needed to understand the exact molecular pathophysiology, stratify patients based on mechanisms involved, and offer individualized and target-directed treatments.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

CMH is supported by the Translational Research Access Programme (TRAP), University of Liverpool, LUPUS UK, the Michael Davies Research Foundation, and the Funding Autoimmuen Research (FAIR) Charity. The Experimental Arthritis Treatment Centre (EATC) for Children is supported by Versus Arthritis UK and the Alder Hey Charity.

References

- 1.Hedrich C.M., Hofmann S.R., Pablik J., Morbach H., Girschick H.J. Autoinflammatory bone disorders with special focus on chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2013;11(1):47. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-11-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmann S.R., Kapplusch F., Girschick H.J., Morbach H., Pablik J., Ferguson P.J. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO): presentation, pathogenesis, and treatment. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2017;15(6):542–554. doi: 10.1007/s11914-017-0405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedrich C.M., Morbach H., Reiser C., Girschick H.J., Basiaga M.L., Vora S.S. New insights into adult and paediatric chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis CNO. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2020 Jul 23;22(9):52. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00928-1. PMID: 32705386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayem G., Bouchaud-Chabot A., Benali K., Roux S., Palazzo E., Silbermann-Hoffman O. SAPHO syndrome: a long-term follow-up study of 120 cases. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;29(3):159–171. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(99)80027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morbach H., Hedrich C.M., Beer M., Girschick H.J. Autoinflammatory bone disorders. Clin. Immunol. 2013;147(3):185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansson A.F., Grote V., Group E.S. Nonbacterial osteitis in children: data of a German incidence surveillance study. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(8):1150–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnabel A., Range U., Hahn G., Siepmann T., Berner R., Hedrich C.M. Unexpectedly high incidences of chronic non-bacterial as compared to bacterial osteomyelitis in children. Rheumatol. Int. 2016;36(12):1737–1745. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3572-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roderick M.R., Shah R., Rogers V., Finn A., Ramanan A.V. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) - advancing the diagnosis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grote V., Silier C.C., Voit A.M., Jansson A.F. Bacterial osteomyelitis or nonbacterial osteitis in children: a study involving the German surveillance unit for rare diseases in childhood. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017;36(5):451–456. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girschick H., Finetti M., Orlando F., Schalm S., Insalaco A., Ganser G. The multifaceted presentation of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: a series of 486 cases from the Eurofever international registry. Rheumatology. 2018;57(8):1504. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wipff J., Costantino F., Lemelle I., Pajot C., Duquesne A., Lorrot M. A large national cohort of French patients with chronic recurrent multifocal osteitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2015;67(4):1128–1137. doi: 10.1002/art.39013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borzutzky A., Stern S., Reiff A., Zurakowski D., Steinberg E.A., Dedeoglu F. Pediatric chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1190–e1197. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh P., Manners P.J., Vercoe J., Burgner D., Murray K.J. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children: nine years’ experience at a statewide tertiary paediatric rheumatology referral centre. Rheumatology. 2015;54(9):1688–1691. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhat C.S., Anderson C., Harbinson A., McCann L.J., Roderick M., Finn A. Chronic non bacterial osteitis- a multicentre study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0290-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu Y., Wu S., Shi X., Chen K., Wu C. Migfilin and Mig-2 link focal adhesions to filamin and the actin cytoskeleton and function in cell shape modulation. Cell. 2003;113(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver M., Lee T.C., Halpern-Felsher B., Murray E., Schwartz R., Zhao Y. Disease burden and social impact of pediatric chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis from the patient and family perspective. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y., Iyer R.S., Reichley L., Oron A.P., Gove N.E., Kitsch A.E. A pilot study of infrared thermal imaging to detect active bone lesions in children with chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71(11):1430–1435. doi: 10.1002/acr.23804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansson A., Renner E.D., Ramser J., Mayer A., Haban M., Meindl A. Classification of non-bacterial osteitis: retrospective study of clinical, immunological and genetic aspects in 89 patients. Rheumatology. 2007;46(1):154–160. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck C., Morbach H., Beer M., Stenzel M., Tappe D., Gattenlohner S. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis in childhood: prospective follow-up during the first year of anti-inflammatory treatment. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010;12(2):R74. doi: 10.1186/ar2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nentwich J., Ruf K., Girschick H., Holl-Wieden A., Morbach H., Hebestreit H. Correction to: physical activity and health-related quality of life in chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020;18(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12969-019-0394-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Kalle T., Heim N., Hospach T., Langendorfer M., Winkler P., Stuber T. Typical patterns of bone involvement in whole-body MRI of patients with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) Röfo. 2013;185(7):655–661. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vittecoq O., Said L.A., Michot C., Mejjad O., Thomine J.M., Mitrofanoff P. Evolution of chronic recurrent multifocal osteitis toward spondylarthropathy over the long term. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(1):109–119. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<109::AID-ANR14>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenbaum J.T. Evolving "diagnostic" criteria for axial spondyloarthritis in the context of anterior uveitis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2016;24(4):445–449. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2016.1158277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aljuhani F., Tournadre A., Tatar Z., Couderc M., Mathieu S., Malochet-Guinamand S. The SAPHO syndrome: a single-center study of 41 adult patients. J. Rheumatol. 2015;42(2):329–334. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colina M., Govoni M., Orzincolo C., Trotta F. Clinical and radiologic evolution of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome: a single center study of a cohort of 71 subjects. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(6):813–821. doi: 10.1002/art.24540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenwood S., Leone A., Cassar-Pullicino V.N. SAPHO and recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Radiol. Clin. 2017;55(5):1035–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaal A., Basiaga M.L., Zhao Y., Egbert M. Pediatric chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis of the mandible: seattle Children’s hospital 22-patient experience. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020;18(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12969-019-0384-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnabel A., Range U., Hahn G., Berner R., Hedrich C.M. Treatment response and longterm outcomes in children with chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. J. Rheumatol. 2017;44(7):1058–1065. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaiser D., Bolt I., Hofer M., Relly C., Berthet G., Bolz D. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis in children: a retrospective multicenter study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2015;13:25. doi: 10.1186/s12969-015-0023-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miettunen P.M., Wei X., Kaura D., Reslan W.A., Aguirre A.N., Kellner J.D. Dramatic pain relief and resolution of bone inflammation following pamidronate in 9 pediatric patients with persistent chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2009;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell J.A., Kodama S.S., Gupta D., Zhao Y. Case series of psoriasis associated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in children with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4(8):767–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khanna G., Sato T.S., Ferguson P. Imaging of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Radiographics. 2009;29(4):1159–1177. doi: 10.1148/rg.294085244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann S.R., Schwarz T., Moller J.C., Morbach H., Schnabel A., Rosen-Wolff A. Chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis is associated with impaired Sp1 signaling, reduced IL10 promoter phosphorylation, and reduced myeloid IL-10 expression. Clin. Immunol. 2011;141(3):317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofmann S.R., Bottger F., Range U., Luck C., Morbach H., Girschick H.J. Serum interleukin-6 and CCL11/eotaxin may Be suitable biomarkers for the diagnosis of chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:256. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofmann S.R., Kubasch A.S., Range U., Laass M.W., Morbach H., Girschick H.J. Serum biomarkers for the diagnosis and monitoring of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) Rheumatol. Int. 2016;36(6):769–779. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fritz J., Tzaribatchev N., Claussen C.D., Carrino J.A., Horger M.S. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: comparison of whole-body MR imaging with radiography and correlation with clinical and laboratory data. Radiology. 2009;252(3):842–851. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2523081335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y., Sato T.S., Nielsen S.M., Beer M., Huang M., Iyer R.S. Development of a scoring tool for chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis magnetic resonance imaging and evaluation of its interrater reliability. J. Rheumatol. 2020 May 1;47(5):739–747. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.190186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnoldi A.P., Schlett C.L., Douis H., Geyer L.L., Voit A.M., Bleisteiner F. Whole-body MRI in patients with Non-bacterial Osteitis: radiological findings and correlation with clinical data. Eur. Radiol. 2017;27(6):2391–2399. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y., Chauvin N.A., Jaramillo D., Burnham J.M. Aggressive therapy reduces disease activity without skeletal damage progression in chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. J. Rheumatol. 2015;42(7):1245–1251. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Girschick H.J., Huppertz H.I., Harmsen D., Krauspe R., Muller-Hermelink H.K., Papadopoulos T. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children: diagnostic value of histopathology and microbial testing. Hum. Pathol. 1999;30(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandt D., Sohr E., Pablik J., Schnabel A., Kapplusch F., Mabert K. CD14(+) monocytes contribute to inflammation in chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO) through increased NLRP3 inflammasome expression. Clin. Immunol. 2018;196:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zimmermann P., Curtis N. The role of Cutibacterium acnes in auto-inflammatory bone disorders. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019;178(1):89–95. doi: 10.1007/s00431-018-3263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saavedra-Lozano J., Falup-Pecurariu O., Faust S.N., Girschick H., Hartwig N., Kaplan S. Bone and joint infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017;36(8):788–799. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedrich C.M., Morbach H., Reiser C., Girschick H.J. New insights into adult and paediatric chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis CNO. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2020;22(9):52. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00928-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y.W., E.Y., Oliver M.S., Cooper A.M., Basiaga M.L., Vora S.S., Lee T.C., Fox E., Amarilyo G., Stern S.M., Devergsten J.A., Haines K.A., Rouster-Stevens K.A., Onel K.B., Cherian J., Hausmann J.S., Miettunen P., Cellucci T., Nuruzzaman F., Taneja A., Barron K.S., Hollander M.C., Lapidus S.K., Li S.C., Ozen S., Girschick H.J., Laxer R.M., Dedeoglu F., Hedrich C.M., Ferguson P.J. The CRMO study group and the CARRA SVARD subcommittee consensus treatment plans for chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis refractory to nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs and/or with active spinal lesions. In preparation. 2017;70(8 August 2018):1228–1237. doi: 10.1002/acr.23462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofmann Srk F., Girschick H.J., Morbach H., Pablik J., Ferguson P.J., Hedrich C.M. Chronic recurrent multi-focal osteomyelitis (CRMO): presentation, pathogenesis and treatment. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2017;15:542–554. doi: 10.1007/s11914-017-0405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Assmann G., Kueck O., Kirchhoff T., Rosenthal H., Voswinkel J., Pfreundschuh M. Efficacy of antibiotic therapy for SAPHO syndrome is lost after its discontinuation: an interventional study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009;11(5):R140. doi: 10.1186/ar2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schilling F., Wagner A.D. [Azithromycin: an anti-inflammatory effect in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis? A preliminary report] Z. Rheumatol. 2000;59(5):352–353. doi: 10.1007/s003930070059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schultz C., Holterhus P.M., Seidel A., Jonas S., Barthel M., Kruse K. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1999;18(11):1008–1013. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199911000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bj0rksten B., Boquist L. Histopathological aspects of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62(3):376–380. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.62B3.7410472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huber A.M., Lam P.Y., Duffy C.M., Yeung R.S., Ditchfield M., Laxer D. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: clinical outcomes after more than five years of follow-up. J. Pediatr. 2002;141(2):198–203. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.126457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jurik A.G. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Semin. Muscoskel. Radiol. 2004;8(3):243–253. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-835364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.King S.M., Laxer R.M., Manson D., Gold R. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: a noninfectious inflammatory process. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1987;6(10):907–911. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198710000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pelkonen P., Ryoppy S., Jaaskelainen J., Rapola J., Repo H., Kaitila I. Chronic osteomyelitislike disease with negative bacterial cultures. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1988;142(11):1167–1173. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150110045017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferguson Pjl R.M. Autoinflammatory bone disorders. In: Petty L., Lindsley Wedderburn, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Rheumatology. seventh ed. Elsevier; 2016. pp. 627–641. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carr A.J., Cole W.G., Roberton D.M., Chow C.W. Chronic multifocal osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(4):582–591. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B4.8331113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bousvaros A., Marcon M., Treem W., Waters P., Issenman R., Couper R. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis associated with chronic inflammatory bowel disease in children. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1999;44(12):2500–2507. doi: 10.1023/a:1026695224019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schilling F., Marker-Hermann E. [Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in association with chronic inflammatory bowel disease: entheropathic CRMO] Z. Rheumatol. 2003;62(6):527–538. doi: 10.1007/s00393-003-0526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hofmann S.R., Kubasch A.S., Ioannidis C., Rosen-Wolff A., Girschick H.J., Morbach H. Altered expression of IL-10 family cytokines in monocytes from CRMO patients result in enhanced IL-1beta expression and release. Clin. Immunol. 2015;161(2):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hofmann S.R., Morbach H., Schwarz T., Rosen-Wolff A., Girschick H.J., Hedrich C.M. Attenuated TLR4/MAPK signaling in monocytes from patients with CRMO results in impaired IL-10 expression. Clin. Immunol. 2012;145(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lucas M., Zhang X., Prasanna V., Mosser D.M. ERK activation following macrophage FcgammaR ligation leads to chromatin modifications at the IL-10 locus. J. Immunol. 2005;175(1):469–477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang X., Edwards J.P., Mosser D.M. Dynamic and transient remodeling of the macrophage IL-10 promoter during transcription. J. Immunol. 2006;177(2):1282–1288. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scianaro R., Insalaco A., Bracci Laudiero L., De Vito R., Pezzullo M., Teti A. Deregulation of the IL-1beta axis in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greenhill C.J., Jones G.W., Nowell M.A., Newton Z., Harvey A.K., Moideen A.N. Interleukin-10 regulates the inflammasome-driven augmentation of inflammatory arthritis and joint destruction. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014;16(4):419. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0419-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morbach H., Hedrich C.M., Beer M., Girschick H.J. Autoinflammatory bone disorders. Clin. Immunol. 2013;147(3):185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakashima T., Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology: crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. J. Clin. Immunol. 2009;29(5):555–567. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakashima T., Takayanagi H. Osteoclasts and the immune system. J. Bone Miner. Metabol. 2009;27(5):519–529. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hofmann S.R., Schnabel A., Rosen-Wolff A., Morbach H., Girschick H.J., Hedrich C.M. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis: pathophysiological concepts and current treatment strategies. J. Rheumatol. 2016;43(11):1956–1964. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paller A.S., Pachman L., Rich K., Esterly N.B., Gonzalez-Crussi F. Pustulosis palmaris et plantaris: its association with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1985;12(5 Pt 2):927–930. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Festen J.J., Kuipers F.C., Schaars A.H. Multifocal recurrent periostitis responsive to colchicine. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1985;14(1):8–14. doi: 10.3109/03009748509102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ben Becher S., Essaddam H., Nahali N., Ben Hamadi F., Mouelhi M.H., Hammou A. [Recurrent multifocal periostosis in children. Report of a familial form] Ann. Pediatr. (Paris) 1991;38(5):345–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferguson P.J., Lokuta M.A., El-Shanti H.I., Muhle L., Bing X., Huttenlocher A. Neutrophil dysfunction in a family with a SAPHO syndrome-like phenotype. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):3264–3269. doi: 10.1002/art.23942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ferguson P.J., El-Shanti H.I. Autoinflammatory bone disorders. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2007;19(5):492–498. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32825f5492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Golla A., Jansson A., Ramser J., Hellebrand H., Zahn R., Meitinger T. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO): evidence for a susceptibility gene located on chromosome 18q21.3-18q22. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;10(3):217–221. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Safra N., Johnson E.G., Lit L., Foreman O., Wolf Z.T., Aguilar M. Clinical manifestations, response to treatment, and clinical outcome for Weimaraners with hypertrophic osteodystrophy: 53 cases (2009-2011) J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013;242(9):1260–1266. doi: 10.2460/javma.242.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ferguson P.J., Bing X., Vasef M.A., Ochoa L.A., Mahgoub A., Waldschmidt T.J. A missense mutation in pstpip2 is associated with the murine autoinflammatory disorder chronic multifocal osteomyelitis. Bone. 2006;38(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grosse J., Chitu V., Marquardt A., Hanke P., Schmittwolf C., Zeitlmann L. Mutation of mouse Mayp/Pstpip2 causes a macrophage autoinflammatory disease. Blood. 2006;107(8):3350–3358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Backues K.A., Hoover J.P., Bahr R.J., Confer A.W., Chalman J.A., Larry M.L. Multifocal pyogranulomatous osteomyelitis resembling chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in a lemur. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001;218(2):250–253. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Majeed H.A., Kalaawi M., Mohanty D., Teebi A.S., Tunjekar M.F., al-Gharbawy F. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia and chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in three related children and the association with Sweet syndrome in two siblings. J. Pediatr. 1989;115(5 Pt 1):730–734. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ferguson P.J., Chen S., Tayeh M.K., Ochoa L., Leal S.M., Pelet A. Homozygous mutations in LPIN2 are responsible for the syndrome of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia (Majeed syndrome) J. Med. Genet. 2005;42(7):551–557. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.030759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Al-Mosawi Z.S., Al-Saad K.K., Ijadi-Maghsoodi R., El-Shanti H.I., Ferguson P.J. A splice site mutation confirms the role of LPIN2 in Majeed syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(3):960–964. doi: 10.1002/art.22431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herlin T., Fiirgaard B., Bjerre M., Kerndrup G., Hasle H., Bing X. Efficacy of anti-IL-1 treatment in Majeed syndrome. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013;72(3):410–413. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lorden G., Sanjuan-Garcia I., de Pablo N., Meana C., Alvarez-Miguel I., Perez-Garcia M.T. Lipin-2 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome by affecting P2X7 receptor activation. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214(2):511–528. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pinto-Fernandez C., Seoane-Reula M.E. Efficacy of treatment with IL-1RA in Majeed syndrome. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2017;45(1):99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roy N.B.A., Zaal A.I., Hall G., Wilkinson N., Proven M., McGowan S. Majeed syndrome: description of a novel mutation and therapeutic response to bisphosphonates and IL-1 blockade with anakinra. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020 Feb 1;59(2):448–451. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aksentijevich I., Masters S.L., Ferguson P.J., Dancey P., Frenkel J., van Royen-Kerkhoff A. An autoinflammatory disease with deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360(23):2426–2437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Reddy S., Jia S., Geoffrey R., Lorier R., Suchi M., Broeckel U. An autoinflammatory disease due to homozygous deletion of the IL1RN locus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360(23):2438–2444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Beck C., Girschick H.J., Morbach H., Schwarz T., Yimam T., Frenkel J. Mutation screening of the IL-1 receptor antagonist gene in chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis of childhood and adolescence. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2011;29(6):1040–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hedrich C.M., Bream J.H. Cell type-specific regulation of IL-10 expression in inflammation and disease. Immunol. Res. 2010;47(1–3):185–206. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8150-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hofmann S.R., Rosen-Wolff A., Tsokos G.C., Hedrich C.M. Biological properties and regulation of IL-10 related cytokines and their contribution to autoimmune disease and tissue injury. Clin. Immunol. 2012;143(2):116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hamel J., Paul D., Gahr M., Hedrich C.M. Pilot study: possible association of IL10 promoter polymorphisms with CRMO. Rheumatol. Int. 2012;32(2):555–556. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1768-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hofmann S.R., Roesen-Wolff A., Hahn G., Hedrich C.M. Update: cytokine dysregulation in chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO) Internet J. Rheumatol. 2012;2012:310206. doi: 10.1155/2012/310206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cox A.D.B., Laxer R., Bing X., Finer A., Erives A., Mahajan V., Bassuk A.G., Ferguson P. Recessive coding and regulatory mutations in FBLIM1 underlie the pathogenesis of sterile osteomyelitis [abstract] Arthritis Rheum. 2016;68(suppl 10) http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/recessive-coding-and-regulatory-mutations-in-fblim1-underlie-the-pathogenesis-of-sterile-osteomyelitis/ [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cox Allison J., Darbro Benjamin W., Laxer Ronald M., Velez Gabriel, Bing Xinyu, Finer Alexis L., Erives Albert, Mahajan Vinit B., Bassuk Alexander G., Ferguson Polly J. Recessive coding and regulatory mutations in FBLIM1 underlie the pathogenesis of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) PLoS One. 2017 Mar 16;12(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169687. eCollection 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xiao G., Cheng H., Cao H., Chen K., Tu Y., Yu S. Critical role of filamin-binding LIM protein 1 (FBLP-1)/migfilin in regulation of bone remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(25):21450–21460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.331249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Abe K., Cox A., Takamatsu N., Velez G., Laxer R.M., Tse S.M.L. Gain-of-function mutations in a member of the Src family kinases cause autoinflammatory bone disease in mice and humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116(24):11872–11877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819825116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Abe K., Fuchs H., Lisse T., Hans W., Hrabe de Angelis M. New ENU-induced semidominant mutation, Ali18, causes inflammatory arthritis, dermatitis, and osteoporosis in the mouse. Mamm. Genome. 2006;17(9):915–926. doi: 10.1007/s00335-006-0014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Abe K., Klaften M., Narita A., Kimura T., Imai K., Kimura M. Genome-wide search for genes that modulate inflammatory arthritis caused by Ali18 mutation in mice. Mamm. Genome. 2009;20(3):152–161. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abe K., Wechs S., Kalaydjiev S., Franz T.J., Busch D.H., Fuchs H. Novel lymphocyte-independent mechanisms to initiate inflammatory arthritis via bone marrow-derived cells of Ali18 mutant mice. Rheumatology. 2008;47(3):292–300. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chitu V., Nacu V., Charles J.F., Henne W.M., McMahon H.T., Nandi S. PSTPIP2 deficiency in mice causes osteopenia and increased differentiation of multipotent myeloid precursors into osteoclasts. Blood. 2012;120(15):3126–3135. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-425595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]