Abstract

This study examined suicidal ideation among Asian immigrant adults in the United States, with consideration of the roles of acculturation and social support. Using the 2002-2003 National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), I conducted latent class analysis with measures of U.S. cultural orientation and Asian ethnic affiliation to create a multidimensional construct of acculturation. Three acculturation groups were identified (assimilated, integrated, separated) that showed different associations with suicidal ideation. Then I analyzed how the association between acculturation status and suicidal ideation is moderated by social support, distinguishing between perceived versus received support. Findings revealed that the buffering role of social support is gender-specific, with perceived support from friends reducing the risk of suicidal ideation only among assimilated women. Implications for future research include further application of acculturation as a multidimensional construct to various health outcomes and behavior as well as to other immigrant subgroups. Public health intervention efforts aimed at preventing suicide should endeavor to promote perceptions of an available social support system among immigrants and aid in establishing sources of support outside the family particularly for immigrant women.

Keywords: Acculturation, Social support, Suicide, Immigrant, Gender, Asian

Highlights

-

•

Latent class analysis with dimensions of exposure to U.S. culture and Asian ethnic affiliation was conducted.

-

•

Integrated and separated groups reported lower odds of suicidal ideation among women whereas no variation existed among men.

-

•

Familial conflict was associated with increased risk of suicidal ideation across gender.

-

•

Perceived friend support reduced risk of suicidal ideation only among assimilated women.

Introduction

Suicide ranks as the tenth leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for approximately one death every 11 min, and in 2018 over 10 million American adults seriously considered suicide (CDC, 2020). Among Asian Americans, suicide as a cause of death ranks even higher: it is the eighth leading cause of death (APA, 2012). While suicide has been widely acknowledged as a social phenomenon, relatively little research has investigated the psychosocial correlates of suicidality among Asian American adults, and even less has focused on Asian immigrants in the U.S. (Duldulao, Takeuchi, & Hong, 2009; Leong, Leach, Yeh, & Chou, 2007; Wong, Uhm, & Li, 2012).

Previous studies examining the relationship between acculturation and suicidality among Asian Americans have found, on the one hand, that a greater level of U.S.-oriented acculturation is associated with heightened risk of suicidality. For example, Wong, Vaughan, Liu, and Chang (2014) revealed that longer proportion of life spent in the U.S. is associated with increased odds of lifetime suicidal ideation among Asian American adults. Similarly, Lee (2016) found that greater proportion of life spent in the U.S. and generational status are associated with increased risks of suicidal ideation and attempt. On the other hand, greater level of U.S.-oriented acculturation has also been discovered to be associated with lower risk of suicidality. Risk of suicidality was greater among those who were less U.S.-acculturated (Lau, Jernewall, Zane, & Myers, 2002), and among those with stronger identification with their heritage cultures (Kennedy, Parhar, Samra, & Gorzalka, 2005). These inconsistent findings indicate that proxies of acculturation, often implicitly equated with assimilation, may likely be capturing limited aspects of cultural adaptation among Asian Americans.

Indeed, acculturation can entail maintenance of original heritage cultures, as implied in segmented assimilation theory (Portes & Zhou, 1993). The question becomes: “into what sector of American society a particular immigrant group assimilates” that enables incorporation into the white middle-class; or leads to downward mobility into the underclass; or facilitates structural adaptation with preservation of ethnic values and networks. While the theory has most widely been applied to structural adaptation, the merit of maintaining ethnic ties can also be applied to health research. Studies have shown that attachment to ethnic communities can enhance the health conditions of immigrants and protect them against stress (Ahmed, Stewart, Teng, Wahoush, & Gagnon, 2008; Stewart, Gagnon, Saucier, Wahoush, & Dougherty, 2008), particularly for women (Ornelas, Perreira, Beeber, & Maxwell, 2009; Viruell-Fuentes & Schulz, 2009). Inspired by this possibility, I argue that acculturation should be operationalized so that it embraces the possible interplay between attachment to the host society as well as to ethnic communities when examining health outcomes and behavior. Reflecting this perspective, I draw on the work of Berry (1970; Sommerlad & Berry, 1970) who identify different acculturation strategies; I consider three of these in this paper.

First, assimilation strategy refers to the adoption of cultural traits of the host society with simultaneous loss of cultural identity from origin-countries. In health research, use of proxies such as English proficiency (e.g., Kang et al., 2010) and duration of residence in the U.S. (e.g., Singh & Lin, 2013) as straight-line measurements of acculturation represents this strategy. Conversely, the strategy of separation is sought by individuals who only wish to maintain their original cultural identity and forgo interaction with the host society. Reports of linguistic isolation (Wong, Yoo, & Stewart, 2007) and its association with poor health (Tsoh et al., 2016) as well as limited utilization of health service use (Kim et al., 2011) belong to a line of health research investigating this strategy. Association between this strategy and such outcomes, in particular, indicates that not all strategies of acculturation are necessarily beneficial to health, similar to the pathway to downward assimilation in segmented assimilation theory (Portes, 2007). Individuals with integration strategy uphold cultural identity from their origin-countries with concurrent pursuit of active interaction with the host society. This strategy in health has been examined by studies of bilingualism and its benefits such as better self-rated physical and mental health (Kimbro, Gorman, & Schachter, 2012) and lower levels of problem behaviors (Han & Huang, 2010) compared to those who are proficient in only English or native language. Possible explanations for such outcomes that center around the capacity to navigate between cultures are in line with segmented assimilation theory and the benefits of maintaining ties to both the host society and ethnic communities. In fact, previous health research involving this strategy extends the applicability of the theory to outcomes beyond structural adaptation.

As such, acculturation is not always a linear process; instead, it manifests in different forms as to enable the concept of selective acculturation (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001) or segmented assimilation (Portes & Zhou, 1993). The breadth of culture, involving behavioral participation in activities and adoption of traits to psychological identification with groups (Snauwaert, Soenens, Vanbeselaere, & Boen, 2003), signals that cultural identity is inevitably multidimensional. Individuals, therefore, may selectively adopt behaviors or traits that they deem advantageous from different cultures (Abraído-Lanza, Armbrister, Flórez, & Aguirre, 2006).

Furthermore, most research on suicidality among Asian Americans has treated the group as aggregate, or was unable to identify significant difference by gender (e.g., Duldulao et al., 2009; Wong et al., 2012), despite wide acknowledgment of suicidality as a gendered phenomenon. Existing research documents that women tend to face greater risk of suicidality (Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, & Baldwin, 2001; Zhang, Mckeown, Hussey, Thompson, & Woods, 2005) than men, a pattern that is shared across race/ethnicity (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Friend, & Powell, 2009), and that factors associated with suicidality also vary by gender (Denney, Rogers, Krueger, & Wadsworth, 2009; Zhang et al., 2005). Only a few studies on Asian Americans, however, have confirmed that women are more likely to report suicidal ideation than men (Wong et al., 2014), and that different psychiatric factors are associated with suicidal ideation (Cheng et al., 2010). As a response, I analyze whether the relationship between acculturation and suicidal ideation manifests differently among Asian immigrant men and women, and compare the role of social support.

Social support can be broadly defined as access to and utilization of individuals, groups, or organizations in face of adverse conditions or stressors in life (Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981). In health research, the role of social support has been primarily investigated through two models. The main effect model examines the statistical main effect of social support on an outcome, based on the notion that it is beneficial to health regardless of whether or not an individual is under stress (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Alternatively, the buffering model examines the interactive effect of social support on an outcome, with the underlying assumption that social support operates through reducing (i.e., buffering) the negative impacts of stress (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Pearlin et al., 1981; Thoits, 1982; Wheaton, 1985). Of note is the distinction between perceived and received social support. Whereas the former refers to the perception of hypothetical availability of support, the latter can be defined as actual receipt of advice, aid, or affect from one's interpersonal networks (Wethington & Kessler, 1986). While studies consistently document a positive association between perceived support and mental health, studies on received support and mental health tend to report no association or, conversely, a negative relationship (Lakey & Orehek, 2011).

Existing studies on the relationship between social support and suicidal behavior among Asian Americans have mostly relied on the main effect model, with little distinction between types of support and heavy emphasis on the role of the family. On the one hand, studies have demonstrated that family can function as a risk factor by being the locus of conflict (Augsberger et al., 2018; Wong, Koo, Tran, Chiu, & Mok, 2011). For example, perceived failure to meet family standards has been found to be positively associated with risk of suicidal ideation (Wang, Wong, & Fu, 2013), and family problems ranked among the top significant events among those who have seriously considered suicide (Wong, Brownson, & Schwing, 2011). Conversely, family can serve as a protector against the risks of suicidal behavior. Levels of family cohesion and suicidal ideation have been found to be negatively associated, particularly among adults with low proficiency in English (Wong et al., 2012). Living with a family member as well as a partner itself is associated with lower odds of reporting morbid thoughts and suicidal ideation (Wong, Brownson, & Schwing, 2011). Family connectedness, likewise, protected against suicide attempt among Asian Americans (Wong & Maffini, 2011). Though less, research has also investigated the role of other sources of social support, such as friends. Experience of social isolation from not only family but also friends precipitated suicidal ideation (Augsberger et al., 2018), and social support from friends was negatively associated with suicidal ideation (Cho & Haslam, 2010) as well as attempt (Wong & Maffini, 2011).

The role of social support, however, can differ by gender, with perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others negatively associated with suicidal behavior only among Asian American women (Park et al., 2015). It has also been demonstrated that whereas family support is negatively associated with psychological distress among women, it is family conflict and perceived community social standing that matter for men (Masood, Okazaki, & Takeuchi, 2009). These findings imply that the role of social support relative to suicidality and mental health more broadly varies by gender. Therefore, I investigate the different roles that types and sources of support play respectively among Asian immigrant men and women.

Specifically, I ask the following research questions. First, how is acculturation associated with suicidal ideation among Asian immigrant adults in the United States? Second, how does social support moderate the relationship between acculturation and suicidal ideation? Third, do these relationships differ by gender? In order to address these questions, I move beyond an assimilationist perspective and operationalize acculturation as a multidimensional construct that involves Asian ethnic affiliation as well as exposure to U.S. culture. I also distinguish between perceived versus received support and analyze whether they play the same or different roles relative to suicidal ideation among men and women. Considering that suicidal ideation is a key predictor of completed suicide along with suicide attempt (Druss & Pincus, 2000), investigating social support as a key buffer against the risk of suicidal ideation among Asian immigrant adults, a population that has received relatively less academic attention, is an important contribution to public health intervention efforts.

Material and methods

Data

This study utilizes data from the 2002–2003 National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), a nationally representative community household survey designed to measure mental and physical health and healthcare access among Latinx and Asian Americans aged 18 and over residing in the United States, excluding institutionalized and military-based populations. A strength of the NLAAS is that it includes a wide range of acculturation measures, both toward the U.S. and country-of-origin. A total of 4649 interviews were completed, drawn using a four-stage national area probability sample with special supplements for adults from selected ethnic groups, including those of Chinese, Filipino, and Vietnamese origin. Altogether, 2095 respondents identified as Asian American. For this study, my analytic sample is restricted to 1637 foreign-born Asians who have valid information on suicidal ideation (867 women and 770 men).

Measures

My dependent variable is a dichotomous measure of lifetime suicidal ideation. In the original questionnaire, respondents were asked whether they have ever seriously thought about committing suicide. A dichotomous measure was created with respondents classified as 1 = yes, and 0 = no.

My main predictor of interest is acculturation. Drawing on theoretical discussions by Berry (1970, 2003) regarding the multidimensional nature of the acculturation process, in this paper acculturation is operationalized based on four criteria: duration of U.S. residence (from less than 5 years to more than 20 years), English proficiency (average score across reading, writing, and speaking English (Cronbach's alpha .97); ranges from 1 to 4), ethnic attachment (average score across three measures (Cronbach's alpha .75): identification with people of same racial and ethnic descent, feelings of closeness to people of same racial and ethnic descent, and amount of time intended to be spent with people of same racial and ethnic descent; ranges from 1 to 4), and native language proficiency (average score across reading, writing, and speaking native language (Cronbach's alpha .92); ranges from 1 to 4). Based on these items, a latent class analysis was conducted, an inductive clustering method that classifies objects similar in their observation values to the same class, the “latent class”, based on identified patterns or selected criteria (Magidson & Vermunt, 2004). The analysis was conducted with a priori categorization of three classes: the assimilated, the integrated, and the separated (Berry, 2003) (see below in the Analysis subsection).

The study adjusts for a series of demographic, socioeconomic and psychosocial characteristics (see Table 2 for specific sample characteristics). Demographic characteristics include age (range: 18 to 95), marital status (1 = married/cohabiting, 0 = all other), family size (range: 1 to 7), and ethnic identity (Chinese, Vietnamese, Filipino, and Other Asian groups). For socioeconomic status, measures of educational level (ranging from 1 = 0–11 years and 4 = 16 or more years), employment status (1 = employed, 0 = unemployed/out of the workforce), and Census 2001 income-to-poverty index are included.

Table 2.

Weighted sample characteristics, foreign-born Asian adults (N = 1637).

| Assimilated (N = 240) |

Integrated (N = 718) |

Separated (N = 679) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Suicidal Ideation, % | .20 | .09 | .07 | .05 | .05 | .09 |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

|

Age at interview, mean |

34.12 (12.92) | 36.64 (14.70) | 40.14 (13.34) | 40.81 (13.24) | 46.95 (13.04) | 47.28 (14.95) |

| Married/Cohabiting, % | .59 | .49 | .76 | .80 | .78 | .77 |

| Family size, mean | 2.85 (1.54) | 2.61 (1.45) | 2.86 (1.57) | 2.85 (1.58) | 3.18 (1.63) | 3.06 (1.63) |

| Ethnic identity, % | ||||||

| Chinese | .27 | .30 | .20 | .23 | .45 | .41 |

| Vietnamese | .08 | .11 | .05 | .09 | .34 | .32 |

| Filipino | .27 | .25 | .28 | .23 | .08 | .09 |

| Other Asian | .38 | .34 | .47 | .44 | .13 | .18 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||||

|

Educational level, mean |

3.14 (.93) | 3.36 (.90) | 3.36 (.87) | 3.46 (.85) | 2.13 (1.13) | 2.32 (1.14) |

| Employed, % | .69 | .80 | .72 | .85 | .63 | .78 |

| Income-to-Poverty index, mean | 6.25 (4.97) | 8.07 (5.48) | 6.73 (5.10) | 6.81 (5.02) | 3.38 (3.87) | 4.02 (3.94) |

| Stress and Support | ||||||

|

Level of acculturative stress, mean |

1.17 (1.19) | .93 (1.12) | 1.53 (1.53) | 1.63 (1.56) | 2.27 (1.83) | 2.38 (1.79) |

| Level of family cultural conflict, mean | 7.14 (2.10) | 6.87 (1.94) | 6.68 (1.79) | 6.29 (1.62) | 6.11 (1.72) | 6.26 (1.75) |

| Frequent attendance at religious services, % | .33 | .27 | .49 | .45 | .33 | .32 |

| Received support from family/relatives, mean | 3.41 (1.22) | 3.02 (1.21) | 3.40 (1.20) | 3.07 (1.15) | 2.88 (1.33) | 2.76 (1.28) |

| Perceived support from family/relatives, mean | 6.23 (1.74) | 5.90 (1.95) | 6.01 (1.86) | 5.56 (1.90) | 4.85 (1.86) | 4.68 (1.85) |

| Received support from friends, mean | 3.32 (1.16) | 3.34 (1.20) | 3.30 (1.21) | 3.13 (1.19) | 2.51 (1.29) | 2.55 (1.32) |

| Perceived support from friends, mean | 6.36 (1.68) | 5.82 (1.79) | 5.64 (1.71) | 5.24 (1.73) | 4.38 (1.75) | 4.43 (1.76) |

| Sample size | 111 | 129 | 371 | 347 | 385 | 294 |

NOTE: Standard deviations in parentheses.

Psychosocial characteristics first include level of acculturative stress, measured as a summed score of nine dichotomous (yes/no) items such as “Do you feel that in the United States you have the respect you had in your country of origin?” Level of family cultural conflict was likewise measured as a summed score of five items, with item response categories ranging from 1 (“hardly ever or never”) to 3 (“often”), to statements such as “You have felt that being too close to your family interfered with your own goals.” For frequent attendance at religious services, respondents were asked “How often do you usually attend religious services?“, which ranged from 1 (“more than once a week”) to 5 (“never”); a dichotomous measure was constructed to reflect those who attend at least once a week (1 = more than once a week/about once a week, and 0 = one to three times a month/less than once a month/never). Received support from family or relatives was measured by frequency of talking on the phone or getting together with family or relatives (ranging from 1 = “less than once a month” and 5 = “most every day”). Perceived support from family or relatives was measured as a summed score of two measures (r = 0.66): feelings of opening up to discuss worries with family or relatives (1 = “not at all” to 4 = “a lot”), and feelings of reliance on family or relatives (1 = “not at all” to 4 = “a lot”). Received support from friends was measured by frequency of talking on the phone or getting together with friends (ranging from 1 = “less than once a month” and 5 = “most every day”), and perceived support from friends was measured as a summed score (r = 0.72) of feelings of opening up to discuss worries with friends (1 = “not at all” to 4 = “a lot”), and feelings of reliance on friends (1 = “not at all” to 4 = “a lot”).

Analysis

As noted above, latent class analysis was conducted with dimensions of exposure to U.S. culture and affiliation with Asian ethnic cultures to obtain classes of acculturation status. As measures of exposure to U.S. culture, duration of U.S. residence and English proficiency1 were utilized, while level of ethnic attachment and native language proficiency composed affiliation with Asian ethnic cultures.2 Analyses with different operationalization of each composite variable (e.g., English proficiency as a summed versus average score across reading, writing, and speaking English) produced three classes with the best model fit using average scores for each composite variable. Then logistic regression models were used to predict suicidal ideation. The sequence of models regressed suicidal ideation on acculturation status with control for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics as well as stress and support measures. Following, tests of moderation were conducted for perceived and received support from family/relatives and friends, the results of which are presented in Model 5.

All analyses are stratified by gender3 and weighted to represent the non-institutionalized Asian immigrant population in the United States. All analyses were run using Stata 16.0 and included “svy” commands to estimate Taylor linearized standard errors to account for the complex sampling frame of the NLAAS. All missing data were multiply imputed using chained equations.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 displays the percentage distribution and mean values for each component of the acculturation measure across the three classes. Class 1 is composed of the “assimilated”, who have stayed long in the United States with high fluency in English, while degree of ethnic attachment and native language proficiency are low: 92 percent have lived in the United States for 11 or more years, and English proficiency is the highest (3.48 out of 4.0), but ethnic attachment and native language proficiency are the lowest among the three classes with a score of 2.91 and 1.67, respectively. Class 2 is comprised of the “integrated”, who have stayed long in the United States with fluency in English, but at the same time they are strongly attached to their ethnic groups and exhibit fluency in their native language: 63 percent have lived in the United States for 11 or more years, English proficiency is high at 3.22 out of 4.0, and ethnic attachment and native language proficiency are also high with scores of 3.34 and 3.69. Last, class 3 includes those who are “separated”, who have stayed long in the United States but show little fluency in English, strong attachment to their ethnic groups and fluency in their native language: 57 percent have lived in the United States for 11 or more years, but English proficiency is the lowest among the three classes with a score of 1.55 out of 4.0, while their score for ethnic attachment is the highest with 3.37 out of 4.0 and also high for native language proficiency with a score of 3.14.

Table 1.

Components of acculturation status measure.

| Acculturation Status |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (Assimilated) | Class 2 (Integrated) | Class 3 (Separated) | |

| Duration of U.S. Residence, % | |||

| Less than 5 years | .04 | .22 | .19 |

| 5–10 years | .04 | .14 | .24 |

| 11–20 years | .40 | .33 | .33 |

| More than 20 years | .52 | .30 | .24 |

| English Proficiency, mean | 3.48 | 3.22 | 1.55 |

| Ethnic Attachment, mean | 2.91 | 3.34 | 3.37 |

| Native Language Proficiency, mean | 1.67 | 3.69 | 3.14 |

| Sample Size | 240 | 718 | 679 |

Table 2 presents weighted sample characteristics for foreign-born Asian adults, stratified by acculturation status and gender. Among women, suicidal ideation rates are four times higher among the assimilated group (20%) when contrasted to those among the separated group (5%), and almost three times higher than the integrated group (7%). Among men, while the rates are less striking, the integrated group reports almost half the rate of suicidal ideation (5%) compared to the assimilated and the separated groups (both 9%).

Demographically, men and women in the separated group are the oldest (mean ages around 47) while both men and women in the assimilated group are the youngest (mean age about 34 and 37, respectively). Rates of marriage/cohabitation are also the lowest among the assimilated group. Family size is largest among the separated group regardless of gender. In terms of ethnic composition, Chinese and Vietnamese respondents comprise the majority among the separated group, whereas among the assimilated and the integrated groups, ‘Other Asian’ comprises the largest proportion.

Socioeconomically, assimilated and integrated Asian immigrants tend to fare better than the separated. The separated group reports much lower levels of education and income, although their employment level is more similar to other groups. The integrated group is the most highly educated regardless of gender, with the highest employment rates. However, when looking at income, assimilated men show the highest income-to-poverty ratio (8.07), while for women income-to-poverty is highest among the integrated group (6.73).

Turning to measures of stress and support, acculturative stress is most severe among the separated group, regardless of gender, followed by the integrated and the assimilated groups. However, assimilated men and women report the highest levels of family cultural conflict. Rates of attendance at religious services are highest among the integrated group, both among men and women. As to support from family/ relatives and friends, among women, on average the assimilated group consistently reports the highest scores across types and sources of support, while the separated group reports the lowest. Among men, likewise, the assimilated group reports the highest level of support (except for received support from family or relatives), whereas the separated group reports the lowest across all types and sources of support.

Logistic regression models predicting suicidal ideation

Table 3, Table 4 present odds ratios from multivariate logistic regression model sequence predicting suicidal ideation stratified by gender. Table 3 shows that among Asian immigrant women in Model 1 (which adjusts for demographic characteristics), both the integrated and the separated groups report significantly lower odds of suicidal ideation compared to the assimilated group (OR = 0.41 [CI: 0.21-0.82] and 0.20 [CI: 0.08-0.46], respectively). Looking across Models 1 through 4, adjusting for control measures has little effect on these relationships. Table 3 also shows that among Asian immigrant women, being married or cohabiting is consistently associated with lower odds of reporting suicidal ideation. When stress and support measures are added in Model 3, Filipinas as well as women in the ‘Other Asian’ group report significantly lower odds of reporting suicidal ideation than Chinese women (OR = 0.37 [CI: 0.19-0.72] and OR = 0.41 [CI: 0.18-0.93], respectively), and higher educational level is associated with lower odds of suicidal ideation (OR = 0.79 [CI: 0.63-0.99]). Importantly, Model 3 shows that level of family cultural conflict is a significant predictor of suicidal ideation, positively associated with the odds of reporting suicidal ideation (OR = 1.37 [CI: 1.20–1.56]). Model 4 also shows that received support from friends is associated with significantly higher odds of reporting suicidal ideation among Asian immigrant women (OR = 1.38 [CI: 1.12–1.69]), whereas perceived support from friends is associated with lower odds in Model 5 (OR = 0.70 [CI: 0.55-0.88]).

Table 3.

Odds ratios from logistic regression models predicting suicidal ideation, Asian immigrant women (N = 867).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturation Status (ref: Assimilated) | |||||

| Integrated | .41* (.21-.82) | .42* (.21-.85) | .44* (.22-.87) | .41** (.21-.80) | .06** (.01-.43) |

| Separated | .20*** (.08-.46) | .19*** (.08-.45) | .20*** (.08-.46) | .21*** (.09-.49) | .02*** (.00-.15) |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||

|

Age at interview |

.99 (.97–1.01) | .99 (.96–1.01) | .99 (.97–1.02) | .99 (.97–1.02) | .99 (.97–1.01) |

| Married/Cohabiting | .34*** (.20-.58) | .31*** (.15-.62) | .33** (.16-.69) | .36** (.17-.75) | .34** (.17-.71) |

| Family size | .89 (.76–1.05) | .91 (.76–1.08) | .95 (.79–1.14) | .95 (.79–1.13) | .94 (.79–1.12) |

| Ethnic identity (ref: Chinese) Vietnamese Filipino Other Asian |

1.07 (.47–2.43) .50 (.23–1.08) .43 (.18–1.03) |

1.06 (.47–2.38) .47* (.22–1.00) .45 (.19–1.07) |

1.05 (.53–2.09) .37** (.19-.72) .41* (.18-.93) |

1.11 (.53–2.32) .39** (.20-.73) .39* (.17-.90) |

1.11 (.50–2.47) .39** (.20-.77) .40* (.18-.89) |

| Ethnic identity (ref: Chinese) | |||||

| Vietnamese | 1.07 (.47–2.43) | 1.06 (.47–2.38) | 1.05 (.53–2.09) | 1.11 (.53–2.32) | 1.11 (.50–2.47) |

| Filipino | .50 (.23–1.08) | .47* (.22–1.00) | .37** (.19-.72) | .39** (.20-.73) | .39** (.20-.77) |

| Other Asian | .43 (.18–1.03) | .45 (.19–1.07) | .41* (.18-.93) | .39* (.17-.90) | .40* (.18-.89) |

| Socioeconomic Status | |||||

|

Educational level |

.86 (.71–1.06) | .79* (.63-.99) | .78* (.62-.99) | .78* (.62–1.00) | |

| Employed | 1.30 (.52–3.24) | 1.22 (.49–3.05) | 1.27 (.52–3.05) | 1.30 (.54–3.16) | |

| Income-to-Poverty index | 1.02 (.96–1.09) | 1.02 (.95–1.10) | 1.03 (.96–1.10) | 1.03 (.96–1.10) | |

| Stress and Support | |||||

|

Level of acculturative stress |

.97 (.82–1.14) | .99 (.84–1.16) | 1.00 (.85–1.17) | ||

| Level of family cultural conflict | 1.37*** (1.20–1.56) | 1.38*** (1.20–1.58) | 1.36*** (1.18–1.57) | ||

| Frequent attendance at religious services | .95 (.40–2.26) | .94 (.41–2.15) | .94 (.41–2.17) | ||

| Received support from family/relatives | 1.05 (.83–1.33) | 1.00 (.79–1.27) | .99 (.78–1.26) | ||

| Perceived support from family/relatives | 1.08 (.89–1.31) | 1.10 (.90–1.34) | 1.08 (.89–1.31) | ||

| Received support from friends | 1.38** (1.12–1.69) | 1.37** (1.12–1.68) | |||

| Perceived support from friends | 1.69).90 (.75–1.07) | .70** (.55-.88) | |||

|

Perceived Support from FriendsAcculturation Status | |||||

| Integrated | 1.37* (1.02–1.83) | ||||

| Separated | 1.55* (1.05–2.29) | ||||

NOTE: 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. *p.05 **p.01 ***p.001.

Table 4.

Odds ratios from logistic regression models predicting suicidal ideation, Asian immigrant men (N = 770).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturation Status (ref: Assimilated) | |||||

| Integrated | .73 (.36–1.47) | .66 (.32–1.35) | .74 (.35–1.55) | .72 (.33–1.57) | .49 (.03–7.5) |

| Separated | 2.04 (.74–5.63) | 2.06 (.74–5.72) | 1.75 (.73–4.21) | 1.48 (.62–3.54) | 1.14 (.17–7.5) |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||

|

Age at interview |

.99 (.97–1.01) | .99 (.97–1.01) | .98 (.96–1.00) | .98* (.96–1.00) | .98* (.96–1.00) |

| Married/Cohabiting | .38* (.16-.94) | .43 (.17–1.09) | .49 (.21–1.14) | .41* (.17-.96) | .41* (.18-.94) |

| Family size | .77* (.59–1.00) | .76* (.59-.98) | .75* (.58-.98) | .75* (.58-.97) | .75* (.58-.98) |

| Ethnic identity (ref: Chinese) | |||||

| Vietnamese | .72 (.39–1.30) | .70 (.38–1.31) | .60 (.31–1.16) | .56 (.29–1.07) | .57 (.29–1.13) |

| Filipino | 2.29* (1.03–5.09) | 2.44* (1.05–5.64) | 2.79* (1.14–6.80) | 2.75* (1.14–6.65) | 2.76* (1.13–6.78) |

| Other Asian | 1.38 (.46–4.16) | 1.25 (.43–3.62) | 1.15 (.42–3.16) | 1.21 (.43–3.40) | 1.23 (.46–3.27) |

| Socioeconomic Status | |||||

|

Educational level |

1.30 (.86–1.97) | 1.31 (.84–2.05) | 1.29 (.84–2.00) | 1.29 (.84–2.00) | |

| Employed | 1.02 (.43–2.44) | .99 (.44–2.26) | 1.00 (.46–2.19) | 1.00 (.46–2.17) | |

| Income-to-Poverty index | .94 (.88–1.01) | .95 (.89–1.01) | .96 (.90–1.02) | .96 (.90–1.02) | |

| Stress and Support | |||||

|

Level of acculturative stress |

1.02 (.78–1.34) | 1.04 (.80–1.37) | 1.05 (.81–1.36) | ||

| Level of family cultural conflict | 1.22** (1.06–1.40) | 1.20** (1.04–1.37) | 1.20** (1.05–1.38) | ||

| Frequent attendance at religious services | 1.02 (.36–2.90) | 1.09 (.37–3.21) | 1.09 (.38–3.18) | ||

| Received support from family/relatives | .86 (.69-1.07) | .92 (.74–1.16) | .92 (.72–1.18) | ||

| Perceived support from family/relatives | .83* (.71-.98) | .85* (.72–1.01) | .86* (.72–1.01) | ||

| Received support from friends | .75 (.54–1.04) | .76 (.53–1.07) | |||

| Perceived support from friends | .98 (.82–1.17) | .93 (.65–1.34) | |||

|

Perceived Support from FriendsAcculturation Status | |||||

| Integrated | 1.07 (.69–1.67) | ||||

| Separated | 1.05 (.76–1.44) | ||||

NOTE: 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. *p.05 **p.01 ***p.001.

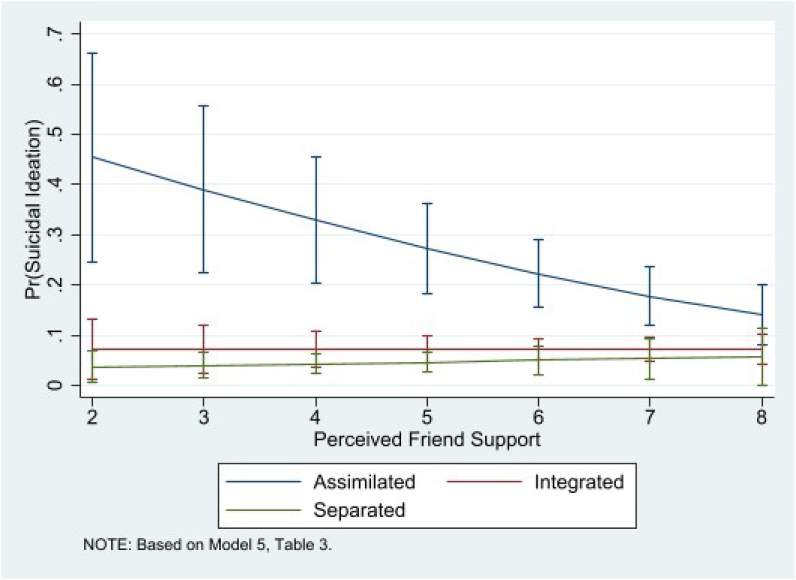

In results not shown, I tested interactions between support from both family or relatives and friends with acculturation status to assess the potential for moderation in these relationships. I found that among Asian immigrant women, perceived support from friends is the only significant interaction term, which I present in Model 5 and graph in Fig. 1. It shows that the predicted probability of suicidal ideation decreases with increased perceived support from friends only among the assimilated group. Because of this, the probability of suicidal ideation is significantly higher among assimilated women who report lower levels of perceived friend support; the gap grows smaller as perceived support increases, but it only closes among women who report the highest level of perceived support. The predicted probability of suicidal ideation among integrated and separated women is similarly low and shows essentially no variation by perceived support from friends.

Fig. 1.

Predicted probabilities of suicidal ideation for Asian immigrant women.

Turning to Table 4, findings show fewer associations with suicidal ideation among Asian immigrant men. In particular, there is no significant association between acculturation status and suicidal ideation, in any model. As with women, being married or cohabiting is associated with lower odds of reporting suicidal ideation, and greater age and family size are associated with significantly lower odds of reporting suicidal ideation among Asian immigrant men. Whereas Filipinas reported significantly lower odds of suicidal ideation than Chinese women, across all models Filipinos report nearly three times the odds of suicidal ideation compared to Chinese men. In terms of social support, level of family cultural conflict continues to be positively associated with the odds of reporting suicidal ideation, whereas perceived support from family or relatives is associated with lower odds of reporting suicidal ideation. In results not shown, all interaction tests between measures of social support and acculturation status were not significant. However, for comparability purposes with results for the women-only sample, in Model 5 I present the findings for the interaction that includes perceived support from friends.

Discussion

Whereas a great deal of scholarship exists on suicidal behavior, less is known about the psychosocial correlates of suicidal behavior among Asian Americans, especially among Asian immigrants in the U.S. (Duldulao et al., 2009; Leong et al., 2007). In recognition of such paucity of research, I aimed to examine the variable types of acculturation, ranging from straight-line assimilation to separation and integration, and their relationships with suicidality among Asian immigrants. Specifically, I analyzed how Asian immigrant adults with distinct experiences of acculturation faced risk of suicidal ideation with social support as a buffer.

To identify acculturation status, latent class analysis with dimensions of exposure to U.S. culture and affiliation with Asian ethnic cultures was conducted, reflecting acculturation as a multidimensional process (Berry, 2003). As measures of the former dimension, duration of U.S. residence and English proficiency were utilized, whereas level of ethnic attachment and native language proficiency composed the latter. Results with the best model fit produced three acculturation groups: the assimilated, the integrated, and the separated group. Variation in suicidal ideation across these groups stood out more strongly among women, with assimilated women reporting the highest rate of approximately 20% while separated women reported the lowest with only a quarter rate in comparison (5%), and integrated women in between with about one third of the rate (7%). Although less dramatic, variation among men was also notable with both assimilated and separated men recording the highest rate of suicidal ideation (9% each) whereas the integrated group reported about half the rate (5%). Thus, it seems that the health benefits of maintaining ties with one's ethnic community, as an extension of segmented assimilation theory (Portes & Zhou, 1993), clearly exist for the immigrant population, demonstrated in particular by rates among the integrated group.

Taking into account social support, findings first showed both direct and buffering roles of social support on suicidal ideation. Across gender, family cultural conflict was positively related to suicidal ideation, whereas only among men, perceived support from family or relatives was associated with reduced odds of reporting suicidal ideation. The strong association between familial support and suicidal ideation adds to existing literature that consistently documents the powerful role of the family relative to suicidality among Asian Americans (Wong & Maffini, 2011; Wong et al., 2012). Among women in particular, the buffering role of perceived friend support has also been identified, among those in the assimilated group who are pushed to seek for support outside the family. For instance, the assimilated group in this study exhibited the highest score of family cultural conflict as well as lowest score of family cohesion (in results not shown), in line with prior research (Kim, 2011; Tsai-Chae & Nagata, 2008; Ying & Han, 2007). They additionally reported the least frequent attendance at religious services. Such lack of venues to garner support may likely have led these individuals to become reliant on their friends, as evidenced by the largest amount of support actually received from friends among the acculturation groups. Indeed, existing research has demonstrated that unmet familial expectations and lack of belongingness to one's family (Augsberger et al., 2018; Wong, Koo, et al., 2011) as well as absence of religious affiliation (Wong, Brownson, & Schwing, 2011) can potentially serve as risk factors of suicidal ideation among Asian Americans. The sense of social isolation that these assimilated individuals experienced, then, may have lent more influence to support from friends compared to other acculturation groups.

Second, differentiation between perceived and received social support yielded opposite findings. Among men, perceived support from family or relatives was associated with lower risk of suicidal ideation. Among women, greater levels of perceived friend support lowered the risks of suicidal ideation particularly among the assimilated group. Conversely, received friend support resulted in increased odds of suicidal ideation among women. These contrasting findings add to existing literature that documents the consistent mental health benefits of perceived support (Cornman, Goldman, Glei, Weinstein, & Chang, 2003; Lakey & Scoboria, 2005; Mossakowski & Zhang, 2014). Received support, on the other hand, has been shown to be negatively or non-significantly linked to mental health (Bolger & Amarel, 2007; Lakey, Orehek, Hain, & VanVleet, 2009; Mossakowski & Zhang, 2014), possibly due to feelings of indebtedness, dependence or incompetence on the part of the recipient (Thoits, 2011). Thus, the positive association between received friend support and suicidal ideation among women may be a manifestation of such feelings shared across acculturation groups.

Third, findings showed that the relationship between acculturation and suicidal ideation, with social support as a moderator, is gender-specific. While the buffering role of perceived friend support was evident among women, it did not surface among men. Previous research has shown that perceived support is negatively associated with suicidality distinctively among women (Park et al., 2015), and that social ties outside the family can especially be beneficial to immigrant women who seek involvement in broader ethnic communities and organizations (Viruell-Fuentes & Schulz, 2009). The gender-dependent moderating role of perceived friend support may be evidence of how the benefits of social support as a buffer can likewise be gendered relative to suicidality. Furthermore, compared to the shared direct associations of familial support, the gender-specific buffering role of perceived friend support sheds light on how sources of support outside the family can particularly be important for immigrant women most strongly involved in U.S. culture.

Despite the importance of this study's findings, it has two main limitations. On the one hand, the current sample was too small to enable stratified analyses by ethnicity or break down of the category of ‘Other Asian’, despite heterogeneity in socioeconomic and immigrant status among Asians (Pew Research Center, 2019). Future research with large enough samples to facilitate such analyses should endeavor to provide detailed explanations for possible ethnic variation. Relatedly, the current analysis drew on data from the NLAAS, collected in 2002–03. While more recent data would be preferable, no other existing study includes information on psychological attachment (e.g., feelings of closeness in ideas to one's racial/ethnic descent) as an integral component of acculturation along with more popular proxies such as duration of residence in the U.S. New data collection efforts are needed that include robust and ethnically diverse samples of U.S. and foreign-born Asian adults, along with detailed information on acculturation and health status.

Nevertheless, this study contributes to existing scholarship on suicidality among Asian Americans. Prior research documenting the relationship between acculturation and suicidal behavior among Asian Americans has largely been limited to one-sided proxies that mostly gauge involvement in U.S. culture (e.g., Lee, 2016; Wong et al., 2014). In light of such limitation, this study examined the association between acculturation and suicidal ideation with a multidimensional framework (Berry, 2003) that simultaneously took into account both U.S. culture involvement and Asian ethnic attachment. Furthermore, while existing research on Asian suicidality has primarily focused on the main effect model (Cohen & Wills, 1985) with little distinction between different types of social support, this study aimed to address such gap by testing for the buffering role of social support as well as distinguishing between perceived and received social support (Wethington & Kessler, 1986). In the endeavor, gender-stratified analyses were conducted in order to investigate the possibly varying associations between acculturation, social support, and suicidal ideation among immigrant men and women.

CRediT author contribution statement

Min Ju Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization

Financial disclosure

No funding has been received.

Ethical statement

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of responsible social science research. I have received an IRB exempt from Rice University because I use nationally representative survey data. Respondents in the study are not identifiable.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

English and native language proficiency were chosen over language preference based on the consistency it has in its relationship with reports of health (see Gee, Walsemann, & Takeuchi, 2010 for an example).

While additional measures of retainment of country-of-origin cultures (e.g., frequency of return visits to country-of-origin) were considered in the initial steps of the analysis (not shown), the present model produced the best model fit and thus was used for present research.

Pooled analysis is available upon request; results are not much different from those found among the women-only sample.

References

- Abraído-Lanza A.F., Armbrister A.N., Flórez K.R., Aguirre A.N. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A., Stewart D.E., Teng L., Wahoush O., Gagnon A.J. Experiences of immigrant new mothers with symptoms of depression. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2008;11:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Suicide among asian Americans. 2012. https://www.apa.org/pi/oema/resources/ethnicity-health/asian-american/suicide Jan 31st 2021.

- Augsberger A., Rivera A.M., Hahm C.T., Lee Y.A., Choi Y., Hahm H.C. Culturally related risk factors of suicidal ideation, intent, and behavior among Asian American women. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2018;9(4):252–261. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.W. Marginality, stress, and ethnic identification in an acculturated aboriginal community. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1970;1:239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.W. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: Chun K.M., Organista P.B., Marin G., editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N., Amarel D. Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: Experimental evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(3):458–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Preventing suicide factsheet.https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/fastfact.html Jan 31st 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.K.Y., Fancher T.L., Ratanasen M., Conner K.R., Duberstein P.R., Sue S. Lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in Asian Americans. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2010;1(1):18–30. doi: 10.1037/a0018799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y.B., Haslam N. Suicidal ideation and distress among immigrant adolescents: The role of acculturation, life stress, and social support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:370–379. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9415-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Wills T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornman J.C., Goldman N., Glei D.A., Weinstein M., Chang M.C. Social ties and perceived support: Two dimensions of social relationships and health among the elderly in Taiwan. Journal of Aging and Health. 2003;15(4):616–644. doi: 10.1177/0898264303256215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denney J.T., Rogers R.G., Krueger P.M., Wadsworth T. Adult suicide mortality in the United States: Marital status, family size, socioeconomic status, and differences by sex. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90(5):1167–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss B., Pincus H. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in general medical illnesses. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(10):1522–1526. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duldulao A.A., Takeuchi D.T., Hong S. Correlates of suicidal behaviors among Asian Americans. Archives of Suicide Research. 2009;13:277–290. doi: 10.1080/13811110903044567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G.C., Walsemann K.M., Takeuchi D.T. English proficiency and language preference: Testing the equivalence of two measures. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):563–569. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W.J., Huang C.C. The forgotten treasure: Bilingualism and Asian children's emotional and behavioral health. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(5):831–838. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.K., Howard D., Kim J., Payne J.S., Wilton L., Kim W. English language proficiency and lifetime mental health service utilization in a national representative sample of Asian Americans in the USA. Journal of Public Health. 2010;32(3):431–439. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M.A., Parhar K.K., Samra J., Gorzalka B. Suicide ideation in different generations of immigrants. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50:353–356. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Intergenerational acculturation conflict and Korean American parents' depression symptoms. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2011;32(11):687–695. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.597017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbro R.T., Gorman B.K., Schachter A. Acculturation and self-rated health among Latino and Asian immigrants to the United States. Social Problems. 2012;59(3):341–363. [Google Scholar]

- Kim G., Worley C.B., Allen R.S., Vinson L., Crowther M.R., Parmelee P. Vulnerability of older Latino and Asian immigrants with limited English proficiency. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(7):1246–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B., Orehek E. Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychological Review. 2011;118(3):482–495. doi: 10.1037/a0023477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B., Orehek E., Hain K.L., VanVleet M. Enacted support's links to negative affect and perceived support are more consistent with theory when social influences are isolated from trait influences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;36(1):132–142. doi: 10.1177/0146167209349375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B., Scoboria A. The relative contribution of trait and social influences to the links among perceived social support, affect, and self‐esteem. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(2):361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J., Friend J., Powell A. Adolescent suicide, gender, and culture: A rate and risk factor analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:402–414. [Google Scholar]

- Lau A.S., Jernewall N.M., Zane N., Myers H.F. Correlates of suicidal behaviors among Asian American outpatient youths. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8(3):199–213. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.Y.S. PhD dissertation, Department of Social Welfare, University of California-Los Angeles; 2016. Acculturation and suicidal risk among Asian Americans and Latinos in California. [Google Scholar]

- Leong F.T.L., Leach M.M., Yeh C., Chou E. Suicide among asian Americans: What do we know? What do we need to know? Death Studies. 2007;31:417–434. doi: 10.1080/07481180701244561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P.M., Rohde P., Seeley J.R., Baldwin C.L. Gender differences in suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):427–434. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidson J., Vermunt J.K. Latent class analysis. In: Kaplan D., editor. The Sage handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Masood N., Okazaki S., Takeuchi D.T. Gender, family, and community correlates of mental health in South Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(3):265–274. doi: 10.1037/a0014301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski K.N., Zhang W. Does social support buffer the stress of discrimination and reduce psychological distress among Asian Americans? Social Psychology Quarterly. 2014;XX(X):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas I.J., Perreira K.M., Beeber L., Maxwell L. Challenges and strategies to maintaining emotional health: Qualitative perspectives of Mexican immigrant mothers. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30(11):1556–1575. [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Sulaiman A.H., Srisurapanont M., Chang S., Liu C.Y., Bautista D. The association of suicide risk with negative life events and social support according to gender in Asian patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2015;228:277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L.I., Menaghan E.G., Lieberman M.A., Mullan J.T. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22(4):337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center . 2019. Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/22/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/ Jan 31st 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Migration, development, and segmented assimilation: A conceptual review of the evidence. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2007;610:73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A., Rumbaut R. University of California Press; 2001. Legacies: The story of the immigrant Second generation. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A., Zhou M. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1993;530(1):74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Singh G.K., Lin S.C. Dramatic increases in obesity and overweight prevalence among Asian subgroups in the United States, 1992-2011. ISRN Preventive Medicine. 2013:1–12. doi: 10.5402/2013/898691. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snauwaert B., Soenens B., Vanbeselaere N., Boen F. When integration does not necessarily imply integration: Different conceptualizations of acculturation orientations lead to different classifications. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2003;3:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerlad E., Berry J.W. The role of ethnic identification in distinguishing between attitudes towards assimilation and integration. Human Relations. 1970;23:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D.E., Gagnon A., Saucier J.F., Wahoush O., Dougherty G. Postpartum depression symptoms in newcomers. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;53(2):121–124. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P.A. Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical problems in studying social support as a buffer against life stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1982;23(2):145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52(2):145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai-Chae A., Nagata D.K. Asian values and perceptions of intergenerational family conflict among Asian American students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(3):205–214. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoh J.Y., Sentell T., Gildengorin G., Le G.M., Chan E., Fung L.C. Healthcare communication barriers and self-rated health in older Chinese American immigrants. Journal of Community Health. 2016;41(4):741–752. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0148-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes E.A., Schulz A.J. Toward a dynamic conceptualization of social ties and context: Implications for understanding immigrant and Latino health. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2167–2175. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.T., Wong Y.J., Fu C.C. Moderation effects of perfectionism and discrimination on interpersonal factors and suicide ideation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60(3):367–378. doi: 10.1037/a0032551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E., Kessler R.C. Perceived support, received support, and adjustment to stressful life events. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1986;27(1):78–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. Models for the stress-buffering functions of coping resources. Journal Of Health And Social Behavior. 1985;26(4):352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.J., Brownson C., Schwing A.E. Risk and protective factors associated with asian American students' suicidal ideation: A multicampus, national study. Journal of College Student Development. 2011;52(4):396–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.J., Koo K., Tran K.K., Chiu Y.C., Mok Y. Asian American college students' suicide ideation: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(2):197–209. doi: 10.1037/a0023040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.J., Maffini C.S. Predictors of asian American adolescents' suicide attempts: A latent class regression analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1453–1464. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.J., Uhm S.Y., Li P. Asian Americans' family cohesion and suicide ideation: Moderating and mediating effects. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(3):309–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.J., Vaughan E.L., Liu T., Chang T.K. Asian Americans' proportion of life in the United States and suicide ideation: The moderating effects of ethnic subgroups. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2014;5(3):237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.T., Yoo G.J., Stewart A.L. An empirical evaluation of social support and psychological well-being in older Chinese and Korean immigrants. Ethnicity and Health. 2007;12(1):43–67. doi: 10.1080/13557850600824104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Y.W., Han M. The longitudinal effect of intergenerational gap in acculturation on conflict and mental health in Southeast Asian American adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(1):61–66. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Mckeown R.E., Hussey J.R., Thompson S.J., Woods J.R. Gender differences in risk factors for attempted suicide among young adults: Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Annals of Epidemiology. 2005;15(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]