Abstract

We report six cases of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, admitted to intensive care unit (ICU), for whom bone marrow aspirate revealed hemophagocytosis. We compared their clinical presentation and laboratory findings to those that can be encountered during a hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. These observations might evoke a macrophage activation mechanism different from the one encountered in the hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

Keywords: Macrophage activation, Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, COVID-19

Introduction

The outbreak of a novel coronavirus named as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei, China in December 2019 raised a worldwide concern. A new cluster was identified in the East of France at the end of February 2020 after a religious meeting of about 2,000 people. In the following weeks, our hospital had to face a massive influx of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. We present a series of six cases of patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in whom bone marrow aspirate revealed hemophagocytosis.

Case Report

We hereby report a series of six cases of patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) in whom bone marrow aspirate revealed hemophagocytosis. COVID-19 diagnosis was confirmed by a positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay of a nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2. The presence of at least one cytopenia justified bone marrow aspirates.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of these six patients are summarized in Table 1. On the day of bone marrow aspirate, four patients had hyperthermia. Clinical examination revealed neither lymphoid tumor syndrome (hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy), nor neurological and cardiological symptoms. Every patient presented either anemia or thrombocytopenia and five patients had lymphopenia. All of them had moderate-to-severe inflammatory syndrome.

Table 1. Clinical and Laboratory Parameters.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | M | M | F | M | M |

| Age | 67 | 63 | 63 | 51 | 69 | 67 |

| Maximum temperature (°C) | 36.1 | 38.1 | 41 | 38.2 | 37.5 | 38.9 |

| Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Leukocytes (109/L) (NR: 4.49 - 12.68) | 13.0 | 23.7 | 10.37 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 2.5 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) (NR: 11.9 - 14.6) | 11.1 | 8.5 | 13.5 | 8.3 | 10.0 | 7.8 |

| Platelets (109/L) (NR: 173 - 390) | 37 | 89 | 53 | 217 | 39 | 71 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) (NR: 2.13 - 4.22) | 1.6 | 2.1 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 7.3 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) (NR: 36 - 220) | 620 | 4,899 | 1,064 | 356 | 801 | 1,206 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) (NR: 0.5 - 1.7) | 1.15 | 5.62 | 2.65 | 7.24 | 1.37 | 1.62 |

| ASAT (UI/L) (NR < 37) | 43 | 84 | 107 | 22 | 71 | 24 |

| H-score | 84 | 207 | 147 | 148 | 35 | 102 |

| Probability of MAS% | 0.56 | 92.10 | 22.0 | 23.0 | 0.10 | 1.70 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) (NR: 1.26 - 3.35) | 1.26 | 1.61 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 0.29 |

| CRP (mg/L) (NR: 0 - 3) | 208 | 278 | 75 | 223 | 129 | 213 |

| PCT (ng/mL) (NR < 0.5) | 20 | 105 | 125.3 | 108.2 | 0.9 | 3.1 |

| Death | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

F: Female; M: male; NR: normal range; ASAT: aspartate amino transferase; MAS: macrophage activation syndrome; CRP: C-reactive protein; PCT: procalcitonin.

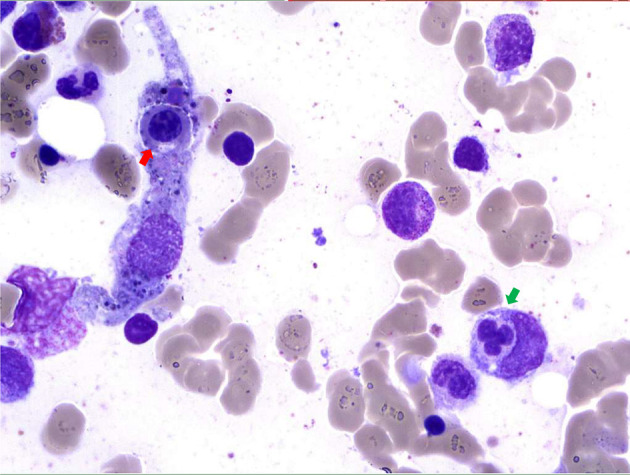

Bone marrow aspirates revealed constantly a rich marrow with abundant pleiomorphic megakaryocytes and the presence of numerous plasma cells. Moreover, hemophagocytosis features (Fig. 1) were observed and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH) was suspected.

Figure 1.

Bone marrow sample (magnification, × 50). May-Grunwald-Giemsa staining of bone marrow aspirate shows two histiocytes with engulfed nucleated cells (one neutrophil (green arrow) and one erythroblast (red arrow)).

All patients were under invasive mechanical ventilation with vasopressor support. Two patients had renal replacement therapy. Three patients required transfusion. Concerning outcome, four patients died during hospitalization, and two patients are still hospitalized.

This retrospective study was approved by local ethics committee.

Discussion

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an immune-mediated life-threatening disease, during which a proinflammatory cytokine production and a tissue infiltration by activated lymphocytes and macrophages occur. This syndrome is characterized by fever, organomegaly (lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly) and cytopenia related to platelets, red blood cells and leukocytes phagocytosis. HLH can progress to a sepsis-like syndrome and a terminal multiple organ failure. The diagnosis is based on clinical, laboratory parameters and histological criteria.

HLH is divided into familial (primary) HLH (pHLH), which occurs in children, adolescents and young adults, characterized by inherited defects of cytolytic pathway proteins, and acquired (secondary) HLH (sHLH), particularly in adults and commonly triggered by infection, malignancy and autoimmunity [1-4].

Viral infections are one of the most frequent trigger factors for HLH. Herpes viruses are the most common triggering agents and among them, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the most frequently incriminated virus [3]. Other viruses triggering HLH are: hepatitis A, B, C, parvovirus B19, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), adenovirus, enterovirus, rubella, measles, respiratory syncytial virus, coxsackie, para-influenza type III, dengue, influenza H1N1 and avian influenza (H5N1) [3, 5]. A case of HLH has also been reported with SARS-CoV-1 [6]. However, this patient concomitantly presented a significant replication of EBV.

Hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow in itself is neither a sensitive nor a specific criterion of HLH [1]. When performing a systematic bone marrow aspirate in thrombocytopenic patients during septic shock in the ICU, prevalence of hemophagocytosis can reach up to 60% [7]. Diagnosis of sHLH may be guided by the H-score [4]. In our series, only one patient has a high H-score in favor of sHLH.

COVID-19 patients’ hemophagocytosis does not share typical clinical and biological features of sHLH, probably pleading for a different mechanism of macrophage activation.

HLH is usually referred to a disorder of histiocytic system characterized by macrophage activation and proliferation. The central abnormality appears to be a cytotoxicity deficiency of natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T cells (CTLs). In the presence of a microorganism, normal but ineffective activation of CTL and NK T lymphocyte system appears, resulting in the persistence of both pathogen and macrophagic antigen-presenting cells. The sustained macrophage activation and homing to the sites of T-cell activation result in tissue infiltration and the production of high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines: tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin 1 (IL-1) and interleukin 6 (IL-6). This activation plays a major role in tissue damage and the resulting clinical symptoms [1, 2, 8].

Macrophage activation in HLH is mediated by indirect activation. Concerning SARS-CoV-2 infection, new pathophysiological data hypotheses could point us towards a different activation mechanism which could be, at least in part, direct.

We know that SARS-CoV-2 uses the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor to penetrate cells [9]. Park reported the results of a preprint by Feng et al [10]. These authors performed pathological analysis of lymph node and splenic tissues. They noted the expression of ACE2 receptors on certain subtypes of macrophages but also the presence of nucleoprotein antigen of SARS-CoV-2 in these cells and showed upregulation of IL-6. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 by binding to ACE2 receptors could modulate expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) [11]. Macrophages express α7 nAChRs subunits and it has been shown that disruption of α7 nAChRs expression could lead to a release of cytokine, particularly TNF-α [12].

During SARS-CoV-2 infection, macrophage activation/modulation appears to play an important role in pathogenesis [13]. Indeed, this infection induces morphological and inflammation-related phenotypic changes in peripheral blood monocytes. A distinct change in the morphology and function of monocytes/macrophages could be predictive of disease severity. Inflammatory macrophages accumulate in lungs and other affected organs and are likely source of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines associated with fatal evolution induced by SARS-CoV-2 [14].

Hemophagocytosis alone and even more sHLH seem to be a poor prognosis factor in SARS CoV-2 infection. Hemophagocytosis indicates macrophage activation. In this situation, it may be partially different from that of HLH, with the possibility of a direct activation mechanism by virus without the need of lymphocytes.

Better comprehension of macrophage activation in SARS-CoV-2 infection may provide an optimal treatment at an early stage, so as to prevent the virus from binding to cell receptors, thus regulating inflammatory response.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

GL, LMJ and AR performed data analysis; GL wrote the first draft, EV, VP, LP, CM, AD, IH, BD, and KK reviewed the manuscript; LMJ, AR, EV, VP, GL, AD, and IH provided patient care and data; all authors reviewed the manuscript and provided final approval.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- 1.Lehmberg K, Ehl S. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2013;160(3):275–287. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter SJ, Tattersall RS, Ramanan AV. Macrophage activation syndrome in adults: recent advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58(1):5–17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Lopez-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1503–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Rosee P, Horne A, Hines M, von Bahr Greenwood T, Machowicz R, Berliner N, Birndt S. et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133(23):2465–2477. doi: 10.1182/blood.2018894618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiab M, Mechinaud F, Harousseau JL. Haemophagocytic syndrome associated with infections. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2000;13(2):163–178. doi: 10.1053/beha.2000.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii H, Asai S, Suzuki T, Eguchi K, Miyachi H. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in an international traveler as a differential diagnosis of SARS. Intern Med. 2005;44(4):342–345. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephan F, Thioliere B, Verdy E, Tulliez M. Role of hemophagocytic histiocytosis in the etiology of thrombocytopenia in patients with sepsis syndrome or septic shock. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(5):1159–1164. doi: 10.1086/516086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arico M, Danesino C, Pende D, Moretta L. Pathogenesis of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2001;114(4):761–769. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR. et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park MD. Macrophages: a Trojan horse in COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):351. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Changeux J-P, Amoura Z, Rey F, Miyara M. doi: 10.5802/crbiol.8. A nicotinic hypothesis for Covid-19 with preventive and therapeutic implications. Qeios [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.qeios.com/read/FXGQSB. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S, Li JH. et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421(6921):384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):355–362. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang D, Guo R, Lei L, Liu HJ, Wang YW, Wang YL, Dai TX. et al. COVID-19 infection induces readily detectable morphological and inflammation-related phenotypic changes in peripheral blood monocytes, the severity of which correlate with patient outcome. medRxiv [Internet]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.24.20042655v1.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.