Pyogenic liver abscess

The diagnosis of pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) represents a challenge for physicians due to their association with multiple pre-existing conditions.

Its incidence varies between 2.3 and 17.59 per 100 000 inhabitants per year,1–3 and in hospitalised patients, it is 8–22 cases per 100 000 hospital admissions.4 Usually occurs in Caucasian men between 50 and 60 years old.5 Risk factors include diabetes mellitus, bacteraemia of non-hepatic origin, immunosuppression, cirrhosis and a history of solid organ transplantation or splenectomy.6–8

Those microorganisms commonly found are specified in table 1. Generally, they are polymicrobial, although single bacteria can be isolated and, in up to 30% of cases, no infectious agent is identified.9

Table 1.

Main microorganisms involved in the aetiology of pyogenic liver abscess

| Pyogenic liver abscess: microorganisms | |

| Gram-negative anaerobic bacilli | Escherichia coli |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |

| Enterobacter spp. | |

| Citrobacter spp. | |

| Gram-positive cocci | Streptococcus spp. |

| Staphylococcus spp. | |

| Enterococcus spp. | |

| Anaerobic bacilli | Clostridium spp. |

| Bacteroides spp. | |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. | |

| Fusobacterium | |

Escherichia coli had been considered the bacterium responsible for the largest number of cases of pyogenic abscesses in the world;10–12 however, it has been found that in Asian countries Klebsiella pneumoniae is one of the main aetiologies,13–15 and its presentation is monomicrobial, usually generates severe clinical conditions due to the hypervirulence and is not related to hepatobiliary diseases.16 17 An invasive syndrome has then been described by serotypes K1 and K2 that are associated with bacteraemia, necrotising fasciitis, endophthalmitis, meningitis and cerebral asbcesses.8 18

PLA can also occur in fungal coinfection by Candida spp., which affects patients with haematological malignancies, and Cryptococcus spp., which has been found in immunosuppressed patients by the HIV, solid organ transplants and primary immunodeficiencies.8

The clinical manifestations are abdominal pain, fever, jaundice, weight loss and chills, similar to an unknown origin fever, sepsis and acute abdomen. The classic triad characterised by fever, jaundice and abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium is only present in 10% of patients; fever is the most frequent symptom, followed by abdominal pain that is in 30% of cases.19 20

Pathogenesis

PLA can be classified according to the origin of the infection that guides its microbiology and consequent therapy:

Biliary

It is the most important cause of liver abscess (LA) with bacterial origin and is given by biliary stasis secondary to a benign or malignant obstruction of the bile duct, such as gallstones and congenital abnormalities, which favours microbial proliferation and invasion of the hepatic parenchyma.21

Portal

Caused by the passage of bacteria through the portal vein to the liver that cause pylephlebitis or infectious suppurative thrombosis, secondary to any intra-abdominal septic process such as loss of intestinal content and peritonitis.21

Bacteremia

Bacterial invasion in the hepatic artery or portal vein, which is generated from a distant focus, usually endocarditis, pneumonia or osteomyelitis. Another source of infection should be suspected other than the abscess if Streptococcus or Staphylococcus is isolated, considering that it spread hematogenously to the liver.22

Direct extension

Generated by infections from adjacent organs to the liver.

Trauma

Caused by a penetrating injury or as a complication of closed trauma.

Diagnosis

General laboratory

In most patients, there is an elevation of acute phase reactants, followed by alterations in liver function tests and, in some cases, anaemia and renal dysfunction.

The acute phase reactants, generally altered, are the count of leucocytes and C reactive protein; leukocytosis is present in more than 80% of patients with suspected PLA23–25 and hence it should always be evaluated.

Liver function tests are non-specific in the different series and they may be normal or altered depending on the cause and extent of the abscess and the development of underlying diseases such as bile duct alterations and hepatic parenchymal ischemia.26

Imaging

Imaging techniques confirm the diagnosis and could determine its aetiology, detect signs of abdominal infection and portosystemic septic thrombosis.

Ultrasound is the modality of choice and it offers high diagnostic accuracy without being associated with complications related to the technique; in fact, it is available frequently, is not invasive, does not generate ionising radiation or require contrast. Its sensitivity for the diagnosis of PLA varies between 86% and 96%27 28 and offers information about the morphology of the abscess, the thickness of the wall, the size of the lesion, presence or absence of septum, hydro-air levels and detritus.

Computed axial tomography (CT scan) has a sensitivity greater than 90% to identify this entity,29 but is more expensive than ultrasound, is less available and generates ionising radiation. The abscess peripherally captures the contrast in the arterial, portal and late phases and allows to see the lesions with better definition (figure 1). This method is recommended in complex patients, after surgical procedures and in interventional radiology procedures as needed.

Figure 1.

Computed axial tomography of a pyogenic liver abscess with hydro-air levels by gram-negative bacteria.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) imaging is a more expensive technique that does not generate radiation for the patient. It is useful when there is evidence of biliary disease or involvement of the hepatic veins, helping to determine if the aetiology has a biliary origin.29 30

These techniques provide information about the number of abscesses, volume of pus, presence of fibrous septa and biliary disease. It also allows to visualise the size of the cavity to define if it requires aspiration with a fine needle prior to puncture with a thick needle to avoid the spillage of pus.29

Microbiology

Isolation of the causative agent may be difficult due to the previous administration of empirical antibiotics that mask the microorganisms responsible for the infection. To achieve this, serial blood cultures and samples guided by radiology of the abscess content are recommended for gram staining and culture.

Complementary diagnostic

The evidence suggests that metastatic infection in the lungs, eyes and brain of PLA without known aetiology should be evaluated routinely, especially when the identified microorganism is K. pneumoniae or when the patient has diabetes mellitus because they are susceptible to septic complications such as bacterial endophthalmitis.31 This microorganism is also associated with colorectal carcinoma (CRC) in the Asian population; it has been shown that CRC causes disruption of the mucosa’s barrier in the colon that generates bacterial translocation through the portal vein;32 33 therefore, colonoscopy should be considered when the patient has a PLA of unknown aetiology, especially if it is caused by K. pneumoniae in the elderly. This early screening could improve the prognosis for these patients.33 34

Treatment

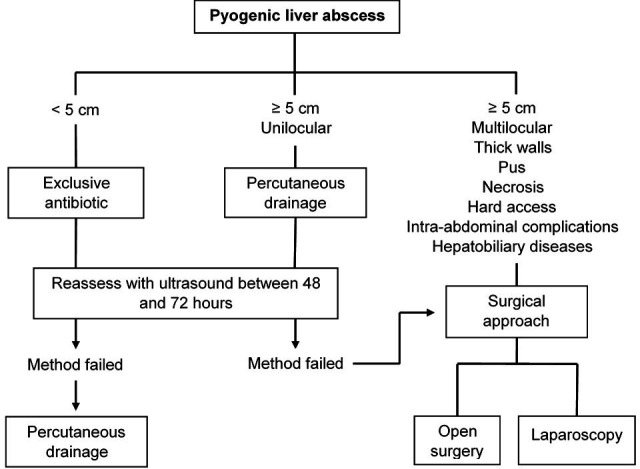

In the 20th century, the treatment was conservative and in severe cases, open surgical drainage was used, but these modalities were associated with mortality rates of up to 80%.29 35 With the implementation of new technologies, the administration of systemic antibiotics and image-guided percutaneous drainage has been positioned as the ideal treatment29 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pyogenic liver abscess treatment approach.

Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotic therapy should be started as soon as possible, after blood sampling for blood cultures, to avoid complications in the patient. Once the microorganism is isolated, the treatment should be reassessed to provide the specific therapy. It should be used as exclusive management if it is not possible to drain the collections due to their size and in patients with high risks of complications associated with the invasive procedure due to their health condition.

For the choice of the empirical antibiotic, multiple factors must be considered, including the possible source of infection, the aetiology, the possibility of nosocomial infections and the bacterial resistance of the environment, to evaluate the best treatment strategy.

As mentioned earlier, the most common bacteria are enterobacteria, streptococci and anaerobes, so the ideal antibiotic management should initially attack these microorganisms. For this, schemes that include last generation cephalosporins plus metronidazole, betalactamases inhibitors plus metronidazole or synthetic penicillins plus aminoglycosides and metronidazole are recommended.21 36 The treatment is administered parenterally for 10–14 days followed by 4 weeks of oral antibiotics, in case of successful drainage of the lesion, otherwise it should be extended up to 6 weeks.8 21 There are reports of shorter schemes, but this will depend on the clinical and imaging response.

Drainage

When PLA is suspected, aspiration and culture of the purulent material have to be performed to confirm the diagnosis and initiate a targeted antibiotic therapy; this method in association with antibiotics has proven beneficial for the treatment of these types of abscesses, although in some cases, when the abscess is small, needle aspiration is sufficient for therapeutic drainage.37 38

In general, LA larger than 5 cm will require rapid drainage for resolution. There are two methods to perform it, surgical drainage and percutaneous drainage, which must be considered as complementary.

Percutaneous drainage is the first-line choice because it is a less invasive technique and with fewer complications than surgical interventions, is successful most of the time and is well tolerated by the patient. Guided by image under local anaesthesia, it allows to aspirate the abscess content to isolate the microorganism responsible for the infection and place drainage tubes to achieve a more rapid resolution of the event. An ultrasound should be performed between 48 and 72 hours to monitor the effectiveness of the management and consider another alternative if required. Complications are rupture of the abscess, contamination of the pleura and subcapsular hematoma.8 Among its disadvantages are catheter occlusion, hepatic haemorrhage, perforation of adjacent organs and which is not useful for managing concomitant hepatobiliary diseases.29 30 If this method fails, open surgical drainage or laparoscopy should be used.

Surgical examination is recommended in large abscesses (>5 cm), multilocular, when the viscous content of the abscess obstructs the catheter, in presence of a underlying process that justifies surgical treatment (eg, complicated cholecystitis laparotomy) and when there is an inadequate response to percutaneous drainage and antibiotic therapy after 1 week.8 21 38 39 The approach can be transperitoneal or posterior transpleural depending on the location of the abscess and the preferences of the surgeon.

The surgical method has advantages over the percutaneous; since it is more direct and precise, it facilitates the simultaneous treatment of several abscesses and addresses the primary diseases associated with them.29 The preferred surgical drainage is laparoscopic; since in general it requires a shorter intervention time, is associated with lower blood losses, decreases the postoperative hospital stay, is less invasive and has advantages in the recovery of gastrointestinal function.29

Complications and prognosis

In general, mortality varies between 3% and 15% depending on when the diagnosis is made, the implementation of an optimal treatment and the conditions of the patient that can worsen the prognosis.17 36 40 The classic complications of LA are rupture, extension of infection to adjacent tissues, sepsis and multiorgan failure. Other situations such as septic shock, biliary pancreatic disease and inflammatory bowel disease may also occur.5 The extreme presentation of this infection is the formation of a gas-forming LA, present in 1%–5% of cases, which generates greater morbidity associated with the accumulation of formic acid.41

Amoebic liver abscess

Amoebiasis is a prevalent infection in developing countries and amoebic liver abscess (ALA) is its most common extraintestinal manifestation. These LAs are solitary, large and located in the right hepatic lobe; differentiating them from other aetiologies is essential to provide the patient with an effective medical therapy.

This entity is caused by Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, Entamoeba moshkovskii and Entamoeba bangladeshi, indistinguishable from each other by microscopy. E. histolytica infection is present in 10% of the world’s population. It is a frequent parasite in tropical areas with poor health and overcrowding conditions, to which 10 000 000 deaths are attributed each year,42 being the second leading cause of death from parasitosis after malaria infection.

Most amoebiasis are asymptomatic and only 1 in 10 patients develop invasive or extra-abdominal diseases such as ALA.42 The infection manifests with a week- long fever, pain in the right hypochondrium, fatigue and hyporexia; therefore, it should be suspected in younger adults, usually men, when the patient has been exposed in an endemic area in the 2 months prior to the onset of symptoms, when he has had a basic dissentive syndrome,8 and in patients in a state of immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, chronic alcoholism and malnutrition, who are more susceptible to developing LA by this protozoan.42 43

Pathogenesis

E. histolytica is a cosmopolitan protozoan belonging to the phylum sarcomastigophora that invades the human being through the ingestion of contaminated food and water, and whose severity of infection depends on genetic factors of both the host and the microoganism.

It has two stages during its life cycle involved in the pathophysiology of the disease: cysts and trophozoites. The first are attributed the acquisition of the infection and the second, the invasion of tissues.

The cysts present in the environment have a chitin cell wall that provides resistance even after being ingested through the consumption of contaminated food and water; in this way, they are resistant to gastric acids and pass without changes to the duodenum.42 In the intestinal lumen, trypsin digests the cyst wall to release four trophozoites that multiply in the colon and penetrate the intestinal mucus layer causing colitis, the death of epithelial cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes. Due to this process, superficial ulcerations, haemorrhages, perforations, enterocolic and cutaneous fistulas develop.

After this invasion, the trophozoites can reach the liver via portal, lymphatic or by direct extension to the peritoneum and hepatic capsule; generally, the parasite causes the rupture of the mesenteric venous system through the cecum and the right colon44 to pass through the portal blood flow and invade the right hepatic lobe that receives more input from this venous system than the left hepatic lobe, which is smaller.8 Once in the liver, trophozoites produce thrombosis and infarction of small areas in the parenchyma triggering an inflammatory response that leads to the formation of abscesses and necrotic foci.

Diagnosis

General laboratory

An altered blood count may be found, with moderate leukocytosis and anaemia depending on the time of evolution, and alterations in liver function tests will depend on the size of the abscess manifested in elevation of bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and transaminases; compared with PLA, hypoalbuminaemia is more common in ALA becoming present in two out of every three patients.45

Imaging

Generally, it is unique, unilocular, located in the right hepatic lobe near the hepatic capsule and may be accompanied by diaphragmatic alterations.46 It is not useful to perform imaging follow-up because it can take up to 9 months to normalise, so the patient’s clinical response must be evaluated.

Ultrasound has a sensitivity greater than 90% to detect this infection.45 The lesion is perceived in 70% of cases as an oval or rounded mass with a diameter between 4 and 12 cm, which is hypoechoic, homogeneous, with low level internal echoes or without them, without wall echoes and distal transmission.45 46

If the ultrasound is negative for ALA, but the clinical suspicion persists, a CT scan is recommended. This technique is more sensitive and offers better resolution in the image for the visualisation of the lesion and its extrahepatic extension towards the pleura and pericardium. The classic finding is a rounded lesion with attenuation values corresponding to complex fluid, with a wall of 3–15 mm, oedema in the periphery, detritus in the cavity and air or haemorrhage46 (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Computed axial tomography of an amoebic liver abscess.

NMR shows spherical lesions similar to pyogenic abscesses, with perilesional oedema and variable intensity according to detritus and necrotic exudate, usually with low signal intensity in the T1 sequence and high intensity in T2.46

Microbiology and complementary tests

The detection of protozoa in the samples of aspirate of the abscess and in faeces is limited, so it should not be essential for diagnosis and to start treatment. Due to their high sensitivity, serological tests for antiamoebic antibodies are recommended with the clarity that titres can persist high even after infection and the detection of antigens by ELISA.21 47

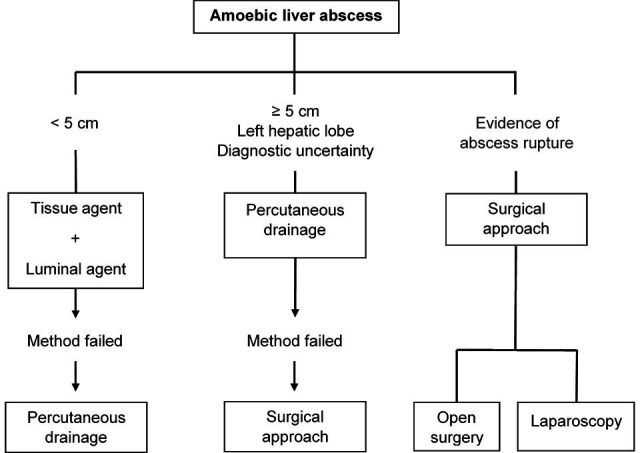

Treatment

It is recommended to implement a conservative treatment consisting of an antimicrobial and minimally invasive drainage according to the indications, avoiding open surgery as much as possible due to its association with high mortality rates43 (figure 4). First-line medical therapy is metronidazole or any other nitroimidazole as an alternative. As adjuvants, luminal amebicides, such as paromomycin sulfate, diloxanide furoate and iodoquinol, can be used (table 2).

Figure 4.

Amoebic liver abscess treatment approach.

Table 2.

Medical treatment of amoebic liver abscess

| Amoebic liver abscess: medical treatment | ||

| Tissue agent | Metronidazole | 500–750 mg orally three times per day for 7 to 10 days |

| Tinidazole | 2 g orally one time per day for 5 days | |

| Nitazoxadine | 500 mg orally two times per day for 10 days | |

| Luminal agent | Paromomycin | 25–30 mg/kg orally per day in three divided doses for 7 days |

| Diiodohydroxyquin | 50 mg orally three times per day for 20 days | |

| Diloxanide furoate | 500 mg orally three times per day for 10 days | |

Percutaneous drainage should be considered in cases of abscesses with a high risk of rupture (> 5 cm) and drainage to pericardium and peritoneum (located in the left hepatic lobe) as well as in those that do not respond to initial therapy and when it persists the suspicion of pyogenic aetiology. However, there is evidence to suggest that drug therapy is sufficient even in abscesses up to 10 cm when they are not complicated.43

If there is evidence of abscess rupture, immediate surgical drainage should be performed unless the rupture is contained and localised peritonitis, in which case ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage can be considered.43

In case of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to colonic disease, endoscopic haemostasis should be implemented48 and the use of blood transfusions, vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma and percutaneous drainage is recommended when there is bleeding in the cavity of the abscess with haemoperitoneum.49

Complications and prognosis

In general, mortality is low, between 0% and 5% if an ideal medical therapy is implemented.43 The most common complication is rupture in adjacent organs: in lung, it is shown with pleural effusion, pneumonia and bronchial fistulas; in peritoneum with peritonitis, it can reach a mortality of 50%; and in mediastinum and pericardium is usually fatal. The perforation of amoebic colitis that causes peritonitis associated with toxaemia, faecal contamination and bacterial infection should also be considered, which increases the risk of mortality.43 Other complications include secondary infections, bleeding in the abscess cavity, hemoperitoneum and those related to catheter placement.49

Conclusion

LA is a rare infection that is associated with high mortality if not treated in a timely manner. It can be caused by multiple microorganisms so its clinical manifestation is variable and can simulate other diseases; hence, an adequate evaluation of the patient’s history that directs the clinical suspicion should be performed. If optimal treatment is offered, this infection has a good prognosis without significant sequelae for patients.

Acknowledgments

To the Gastrohepatology Research Group and Hepatology Department of the Hospital Pablo Tobon Uribe for the academic support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @TrillosAlmanza

MCT-A and JCRG contributed equally.

Contributors: JCRG raised the subject of revision, contributed to the writing of the article and made its final revision. MCTA carried out the systematic search of articles, their revision and writing of the text.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Meddings L, Myers RP, Hubbard J, et al. A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:117–24. 10.1038/ajg.2009.614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsai F-C, Huang Y-T, Chang L-Y, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess as endemic disease, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:1592–600. 10.3201/eid1410.071254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-Based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:1032–8. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00459-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chadwick M, Shamban L, Neumann M. Pyogenic liver abscess with no predisposing risk factors. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2018;2018:1–4. 10.1155/2018/9509356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kubovy J, Karim S, Ding S. Pyogenic liver abscess: incidence, causality, management and clinical outcomes in a new Zealand cohort. N Z Med J 2019;132:30–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tian L-T, Yao K, Zhang X-Y, et al. Liver abscesses in adult patients with and without diabetes mellitus: an analysis of the clinical characteristics, features of the causative pathogens, outcomes and predictors of fatality: a report based on a large population, retrospective study in China. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18:E314–30. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruiz-Hernández JJ, León-Mazorra M, Conde-Martel A, et al. Pyogenic liver abscesses: mortality-related factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;19:853–8. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282eeb53b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rossi G, Lafont E, Rossi B, et al. Abceso hepático colloids surfaces. A Physicochem Eng Asp 2019;22:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:1654–9. 10.1086/425616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seeto RK, Rockey DC. Pyogenic liver abscess. changes in etiology, management, and outcome. Medicine 1996;75:99–113. 10.1097/00005792-199603000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lederman ER, Crum NF. Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:322–31. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corredoira Sánchez JC, Casariego Vales E, Ibáñez Alonso MD, et al. [Pyogenic liver abscess: changes in etiology, diagnosis and treatment over 18 years]. Rev Clin Esp 1999;199:705–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang FY, Chou MY. Comparison of pyogenic liver abscesses caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae and non-K. pneumoniae pathogens. J Formos Med Assoc 1995;94:232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chung DR, Lee SS, Lee HR, et al. Emerging invasive liver abscess caused by K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. J Infect 2007;54:578–83. 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lok K-H, Li K-F, Li K-K, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: clinical profile, microbiological characteristics, and management in a Hong Kong Hospital. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2008;41:483–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guzmán-Silva MA, Santos HLC, Peralta RS, et al. Experimental amoebic liver abscess in hamsters caused by trophozoites of a Brazilian strain of Entamoeba dispar. Exp Parasitol 2013;134:39–47. 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siu LK, Yeh K-M, Lin J-C, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:881–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70205-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chia DWJ, Kuan WS, Ho WH, et al. Early predictors for the diagnosis of liver abscess in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med 2019;14:783–91. 10.1007/s11739-019-02061-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Foo N-P, Chen K-T, Lin H-J, et al. Characteristics of pyogenic liver abscess patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:328–35. 10.1038/ajg.2009.586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hernández JL, Ramos C. Pyogenic hepatic abscess: clues for diagnosis in the emergency room. Clin Microbiol Infect 2001;7:567–70. 10.1046/j.1198-743x.2001.00323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akhondi H, Sabih DE. Liver abscess, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abbas MT, Khan FY, Muhsin SA, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of liver abscess: a single reference center experience in Qatar. Oman Med J 2014;29:260–3. 10.5001/omj.2014.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mavilia MG, Molina M, Wu GY. The evolving nature of hepatic abscess: a review. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2016;4:158–68. 10.14218/JCTH.2016.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ioannou A, Xenophontos E, Karatsi A, et al. Insidious manifestation of pyogenic liver abscess caused by Streptococcus intermedius and Micrococcus luteus: a case report. Oxford Med case reports 2016;1:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reyna-Sepúlveda F, Hernández-Guedea M, García-Hernández S, et al. Epidemiology and prognostic factors of liver abscess complications in northeastern Mexico. Med Univ 2017;19:178–83. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lardière-Deguelte S, Ragot E, Amroun K, et al. Hepatic abscess: diagnosis and management. J Visc Surg 2015;152:231–43. 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McKaigney C. Hepatic abscess: case report and review. West J Emerg Med 2013;14:154–7. 10.5811/westjem.2012.10.13268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin AC-M, Yeh DY, Hsu Y-H, et al. Diagnosis of pyogenic liver abscess by abdominal ultrasonography in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2009;26:273–5. 10.1136/emj.2007.049254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tu J-F, Huang X-F, Hu R-Y, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open surgery for pyogenic liver abscess with biliary pathology. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4339–43. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i38.4339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Santos-Rosa OMD, Lunardelli HS, Ribeiro-Junior MAF. Pyogenic liver abscess: diagnostic and therapeutic management. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2016;29:194–7. 10.1590/0102-6720201600030015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dulku G, Tibballs J. Cryptogenic invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome (CIKPLA) in Western Australia? Australas Med J 2014;7:436–40. 10.21767/AMJ.2014.2188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jeong SW, Jang JY, Lee TH, et al. Cryptogenic pyogenic liver abscess as the herald of colon cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:248–55. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mohan BP, Meyyur Aravamudan V, Khan SR, et al. Prevalence of colorectal cancer in cryptogenic pyogenic liver abscess patients. do they need screening colonoscopy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2019;51:1641–5. 10.1016/j.dld.2019.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lai H-C, Lin C-C, Cheng K-S, et al. Increased incidence of gastrointestinal cancers among patients with pyogenic liver abscess: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2014;146:129–37. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heneghan HM, Healy NA, Martin ST, et al. Modern management of pyogenic hepatic abscess: a case series and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:80. 10.1186/1756-0500-4-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yoon JH, Kim YJ, Il KS. Prognosis of liver abscess with no identified organism, 2019: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Serraino C, Elia C, Bracco C, et al. Characteristics and management of pyogenic liver abscess: a European experience. Medicine 2018;97:e0628. 10.1097/MD.0000000000010628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mukthinuthalapati VVPK, Attar BM, Parra-Rodriguez L, et al. Risk factors, management, and outcomes of pyogenic liver abscess in a US safety net Hospital. Dig Dis Sci 2019;125. 10.1007/s10620-019-05851-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pickens RC, Jensen S, Sulzer JK, et al. Minimally invasive surgical management as effective first-line treatment of large pyogenic hepatic abscesses. Am Surg 2019;85:813–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pang TCY, Fung T, Samra J, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: an audit of 10 years' experience. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:1622–30. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kosasih S, Chong PL, Chong VH, et al. Gas forming pyogenic liver abscess. QJM 2019;112:145–6. 10.1093/qjmed/hcy209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morf L, Singh U. Entamoeba histolytica: a snapshot of current research and methods for genetic analysis. Curr Opin Microbiol 2012;15:469–75. 10.1016/j.mib.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kumar R, Anand U, Priyadarshi RN, et al. Management of amoebic peritonitis due to ruptured amoebic liver abscess: It’s time for a paradigm shift. JGH Open 2019;3:268–9. 10.1002/jgh3.12144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Herrera JL, Knudsen CD. Chapter 30 liver abscess. 5th edn. GI/Liver Secrets Plus. Elsevier Inc, 2019: 237–42. 10.1016/B978-0-323-26033-6/00030-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wuerz T, Kane JB, Boggild AK, et al. A review of amoebic liver abscess for clinicians in a nonendemic setting. Can J Gastroenterol 2012;26:729–33. 10.1155/2012/852835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bächler P, Baladron MJ, Menias C, et al. Multimodality imaging of liver infections: differential diagnosis and potential pitfalls. Radiographics 2016;36:1001–23. 10.1148/rg.2016150196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stanley SL. Amoebiasis. Lancet 2003;361:1025–34. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Premkumar M, Devurgowda D, Dudha S, et al. Clinical and endoscopic management of synchronous amoebic liver abscess and bleeding colonic ulcers. J Assoc Physicians India 2019;67:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sharma N, Kaur H, Kalra N, et al. Complications of catheter drainage for amoebic liver abscess. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2015;5:256–8. 10.1016/j.jceh.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]