Abstract

Corticosteroids remain an important tool for inducing remission in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) but they have no role in maintenance of remission. The significant adverse side effect profile of these drugs means their use should be avoided where possible or measures taken to reduce their risk. Despite an expanding array of alternative therapies, corticosteroid dependency and excess remain common. Appropriate steroid use is now regarded a key performance indicator in the management of IBD. This article aims to outline indications for corticosteroid use in IBD, their risks and strategies to reduce their use and misuse.

Keywords: steroid-sparing efficacy, inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, crohn's disease, 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA)

Key points.

Steroids have wide ranging and sometimes devastating side effects.

Steroids have no place in maintenance therapy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Steroid dependency and excess are common and often avoidable in IBD.

Alternatives to systemic corticosteroids, including 5-aminosalicylic acid, budesonide and beclomethasone, should be explored and timely introduction of an immunomodulator and/or biologic is essential.

Dedicated IBD clinics, telephone helplines and multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) can reduce steroid excess. IBD services should audit corticosteroid use on a regular basis.

IBD services should signpost primary care physicians to the IBD toolkit and flare pathways (www.rcgp.org.uk/ibd) to support the management of IBD out of hours in the community.

Steroids should be tapered appropriately to minimise the risk of adrenal insufficiency.

All patients with IBD on steroids should have adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation for bone protection and be considered for bisphosphonates where appropriate.

Introduction and history of corticosteroid use

Truelove and Witts were the first to trial cortisone, referred to as ‘the special tablets’, to induce remission in ulcerative colitis (UC).1 Two-thirds in the treatment arm either improved or entered full clinical remission compared with about one-third of those treated with the standard medical therapy of the time.1 Later corticosteroids were reported to be efficacious for the induction of remission in Crohn’s disease (CD) with three-quarters of patients initially improving.2 However, it became apparent that the long-term benefits of corticosteroids for patients with IBD were less favourable and associated with a wide range of significant side effects.3 4 Despite an expanding array of new therapies now available, corticosteroids remain an important tool in the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) but must be used judiciously.

Indications for corticosteroids in IBD

Induction of remission in UC

Corticosteroids are effective agents for inducing remission in UC. A meta-analysis found patients treated with systemic corticosteroids were twice as likely to enter remission compared with patients who received a placebo.4 Oral steroids are also superior to 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) in this context, with higher rates of clinical remission (76% vs 52%, p<0.05) and improvement in endoscopic appearances (78% vs 43%, p<0.05), though due to corticosteroids’ side effect profile 5-ASA remains the first-line therapy for mild to moderate UC.5 In patients with severe UC, corticosteroids are recommended first-line either orally or, in the case of acute severe UC (ASUC), intravenously. BSG guidelines recommend either hydrocortisone 100 mg intravenous six hourly or methylprednisolone 60–80 mg intravenous daily as the initial treatment for ASUC.6 Methylprednisolone has less mineralocorticoid potency than hydrocortisone, so may be preferred in patients with hypokalaemia.7 One in three patients with ASUC will not respond adequately to parenteral corticosteroids and normally on the third day of admission patients should be reassessed and considered for rescue therapy with infliximab or ciclosporin, as appropriate, or colectomy as the clinical picture dictates.8–10 BSG recommendations suggest that, provided colectomy does not take place, parenteral corticosteroids should be continued until the patient is passing less than four stools per day with no blood for two consecutive days. Once this threshold is reached parenteral corticosteroids can be switched to oral Prednisolone 40 mg daily, which should then be appropriately tapered. If colectomy is undertaken, an appropriately prompt steroid taper should be closely supervised postoperatively.11 12

Induction of remission in CD

Guidelines recommend the use of corticosteroids for inducing remission in ileocolonic CD.6 Budesonide (Budenofalk and Entocort) formulated to release in the ileum and proximal colon, taken orally 9 mg daily for 8 weeks is recommended as the first line agent in mild-to-moderate ileocaecal CD, marginally less effective than systemic steroids but with a significantly better side effect profile.6 13 14 Systemic corticosteroids still have a place for inducing remission in more severe ileal or ileocaecal and colonic disease (table 1).14 15

Table 1.

Indications and suggested regimens for corticosteroids in IBD

| Type | Target | Indication | Suggested dose |

| Hydrocortisone 10% foam enema | Rectum, Sigmoid | Proctitis, Proctosigmoiditis | 1–2 metered applications (equivalent of 90 mg) per day for 2–3 weeks, then once daily alternate days |

| Budesonide rectal foam | Rectum, Sigmoid | Proctitis, Proctosigmoiditis | one metered application (equivalent of 2 mg) once daily for up to 8 weeks |

| Budesonide pH-dependent | Ileum, Right Colon | Mild to moderate ileocaecal CD | 9 mg daily for 8 weeks, taper over 1–2 weeks |

| Budesonide MMX |

Colon | Mild to moderate UC | 9 mg daily for 8 weeks |

| Beclamethasone dipropionate | Colon | Mild to moderate UC | 5 mg daily for 4 weeks, followed by 5 mg every other day for 4 weeks |

| Prednisolone | Systemic | Moderate to severe UC Moderate to severe CD (not penetrating) |

40 mg daily, tapering over 6–8 weeks |

| Hydrocortisone | Systemic | Acute severe UC | 100 mg intravenous 6 hourly, switch to 40 mg Prednisolone OD after 2 days of passing <4 stools per day with no blood |

| Methylprednisolone | Systemic | Acute severe UC | 60–80 mg intravenous daily, switch to 40 mg prednisolone once daily after 2 days of passing <4 stools per day with no blood |

CD, Crohn’s disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Misuse of steroids

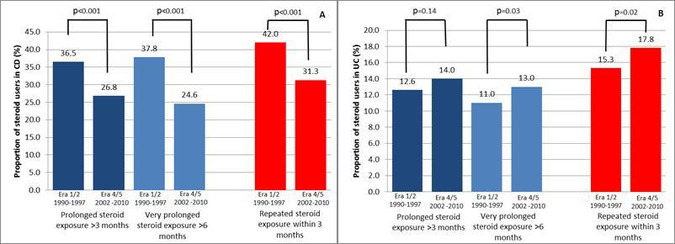

Corticosteroids have no role in the maintenance of remission for either CD or UC as there is clear evidence they lack of efficacy in this respect.16 17 In spite of this, one in four individuals in the UK with CD and one in eight with UC have prolonged steroid exposure for greater than 6 months (figure 1) within the first 5 years of diagnosis and this is mirrored in Europe, Canada and the USA.18–22 This carries with it a substantial burden of corticosteroid related side effects, including increased rates of infection, adrenal suppression, osteoporosis, diabetes, cardiovascular events, mood disorders and all-cause mortality—a more detailed description of common side effects can be found below.23–26 BSG guidelines state that prolonged steroid use is harmful and should be avoided, similarly the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America regard steroid-free remission as a treatment target.6 27

Figure 1.

Proportion of prolonged steroid exposure (>3 months use and >6 months use) and repeated steroid exposure (restarting steroids within 3 months of previous course), adjusted for age and sex using logistic regression, within 5 years of diagnosis between era 1/2 and era 4/5 for Crohn’s disease (CD) (A) and ulcerative colitis (UC) (B). χ2 test for trend used to compare proportion between groups. Follow-up period 1990–2010. Reproduced with permission from Chhaya et al 18.

European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation and BSG guidelines define steroid dependency as an inability to wean prednisolone below 10 mg per day within 3 months without recurrent active disease, or symptomatic relapse of IBD within 3 months of stopping steroids requiring recommencement.6 28 Early escalation of treatment with the introduction of steroid sparing agents such as immunomodulators like azathioprine or a biologic agent is advocated in such patients.6 27 29–31

A multicentre audit of 1176 UK patients with IBD examined rates of steroid dependency or excess, where excess was defined as more than one course of steroids in a 12-month period.32 It found that in the course of a year 14.9% of patients met the definition of steroid dependency or excess, half of which was deemed to be avoidable. Where corticosteroids had been prescribed in primary care 91% of steroid dependency or excess was deemed avoidable, although it should be noted that primary care prescriptions only accounted for a minority of the total burden of steroid excess. Self-medication may also contribute to steroid dependency and around 15% of patients with IBD report self-medicating with corticosteroids.33 34 Steroid dependency continues to be a significant issue and although prescription rates may have begun to decline among CD patients, in UC their use has continued to rise (figure 1).18 32 35–38

Elderly patients with IBD appear to be at particular risk of steroid misuse. In a study of 20 hospitals in Pennsylvania, one-third of patients 65 years or older received prednisone for more than 6 months.39 The same study found steroid use rose from 36.3% in the era 1991–2000 to 63.7% in the era 2001–2010. Likewise, another study at a tertiary IBD clinic found 24% of elderly patients in clinical remission or with mild disease activity were maintained on long-term corticosteroids.40 This might be explained by the fact steroid sparing therapies such as thiopurines and antitumour necrosis factor (TNF) therapy are used much less frequently in the elderly IBD population.39 40 Among elderly patients with IBD receiving corticosteroids only 37% received thiopurines and just 21% were treated with a biologic agent.40 The reluctance to use thiopurines and biologics in elderly patients likely stems from concerns about the safety of these medications in this population, notably the risk of infection and malignancy. However, avoiding these drugs and employing corticosteroids as an alternative is likely to be particularly deleterious in the elderly since corticosteroid related infection, osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus and depression are significantly increased in this age group.41 42

Reducing steroid use and misuse

Suitable alternatives to steroids should always be considered. Guidelines recommend 5-ASA should be used first-line before corticosteroids for inducing remission in mild to moderate UC, reserving corticosteroids for refractory cases.6 Before starting corticosteroids the addition of a 5-ASA enema to oral 5-ASA should also be considered as this increases rates of mucosal healing and reduces time to the resolution of symptoms, regardless of UC disease extent.43 44 In proctitis, first-line treatment is topical 5-ASA as it is both better tolerated and more effective than steroid enemas, which are a second line alternative before the introduction of oral steroids.45 46 Combination therapy of topical 5-ASA and topical corticosteroids may offer a benefit over monotherapy; a study of 60 patients with proctitis found the combination of 2 g 5-ASA enemas and 3 mg beclomethasone diproprionate (BPD) enemas daily for 28 days was superior to either therapy alone for achieving clinical improvement (5-ASA/BPD 100% vs BPD 70% vs 5-ASA 76%).47 However, this finding was not replicated in a recent large, well-performed randomised control trial comparing Budesonide and 5-ASA suppositories as combination or monotherapy for treating proctitis.48 Budesonide foam has a low incidence of adverse events, similar to patients receiving placebo.49 In particular serum cortisol concentrations do not appear to be significantly affected. However, whether there is an advantage to using this second-generation topical corticosteroid instead of cheaper hydrocortisone foam remains unclear, as both appear to have similar efficacy and safety profiles.50

In CD exclusive enteral nutrition is effective, if tolerated, for the induction of remission as an alternative to steroids particularly if surgery is being contemplated.6 51

Where steroid use is unavoidable in ileal and ileocaecal CD, budesonide (Entocort or Budenofalk) is indicated for mild to moderate disease.52 Likewise in UC, it may be appropriate to prescribe budesonide MMX (Cortiment) or beclomethasone (Clipper) to induce remission.53 54 These agents have a low systemic bioavailability and therefore a more favourable side effect profile compared with conventional steroids.55 56 However, budesonide is underused with only 11% of individuals diagnosed with CD being prescribed Budesonide within 3 years of diagnosis, despite an estimated one-third of patients fulfilling the criteria for its use.57 In some healthcare systems, the relative cost of second-generation corticosteroids compared with prednisolone may be a barrier to their use,58 for example, one study in the USA found less than 1% of patients with IBD were prescribed budesonide between 2001 and 2010.39 Set against this is the considerable health-economic burden of treating side effects from long-term systemic steroids.59 60

Maintenance therapy with anti-TNF has been associated with reduced steroid excess in CD (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.95), however, an equivalent benefit in UC was not found, although the study was potentially underpowered in this regard.61 Akin to this finding from the UK, a nationally representative study from the USA of 8502 patients with IBD found one in five anti-TNF users were concomitantly using steroids for 6 months or more.62 When initiating maintenance therapy clinicians should be aware that timely induction of some faster onset agents, such as anti-TNF agents, may not necessarily require bridging steroids while others with a slower onset of action, for example, thiopurines, will do.

An increasing array of therapies has demonstrated steroid-sparing potential in IBD, including thiopurines, anti-TNF agents, vedolizumab, ustekinumab and tofacitinib.63–72 However, timely escalation, when a patient is either corticosteroid refractory or dependent, is not carried out in significant proportion of cases, leading to inappropriate steroid excess.32 The choice of therapy should be made on an individual basis and take into account the side effect profile with particular consideration given to risk of malignancy or infection or other recognised contraindications, route of administration, risk of immunogenicity and cost.6

Organisational factors are also important determinants of the risk of steroid excess. In a study of 20 hospitals, 11 introduced quality improvement projects to educate patients and clinicians regarding steroid use and improve access to specialist advice through telephone helplines and rapid access clinics. Patients attending hospitals where the intervention was implemented were less likely to use steroids to excess (11.5% vs 17.1%, p<0.001).61 There is also evidence that dedicated IBD clinics are associated with less excessive use of steroids in UC.32 Likewise, a dedicated IBD multidisciplinary meeting is key to reducing inappropriate steroid excess in both CD (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.83) and UC (OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.73).61

The recently published UK IBD Standards state that steroid use should be audited regularly, ideally on an annual basis, and a dedicated online steroid assessment tool is available for this purpose.73 This simple tool can easily be used ‘live’ in clinic. The introduction of the IBD benchmarking tool may also act as a stimulus to IBD services to monitor steroid use more closely and take measures to reduce steroid misuse. Recently, the UK IBD registry has also started to evaluate steroid use in their annual report.35 A specific target for rates of steroid dependency and excess has yet to be fully defined and this may vary between different patient populations.61 By annually auditing steroid use, individual services can determine the local burden of inappropriate steroid excess and take steps to reduce it.

Barriers to specialist advice are likely to contribute to high rates of avoidable steroid excess in primary care. Aside from support through IBD advice lines and rapid access clinics, education may also play a role in reducing steroid misuse in IBD.74 The IBD Spotlight Project, is a collaboration between Crohn’s and Colitis UK, The Royal College of General Practitioners and the BSG. It has developed an IBD toolkit and e-learning module to guide primary care physicians’ management of IBD (www.rcgp.org.uk/ibd).75 This includes IBD flare-pathways for both CD and UC and IBD services should signpost primary care clinicians to these resources.

Management of common side effects

Several steps can be taken to reduce the significant side effect profile of corticosteroids. Adrenal insufficiency occurs in roughly one-third of patients receiving corticosteroids, particularly but not exclusively, in those exposed to high dose and long courses of corticosteroids.76 77 Guidelines recommend tapering corticosteroids in IBD, but practice varies greatly.6 78–80 BSG guidelines recommend moderate to severe UC should be treated with 40 mg prednisolone tapered over 6–8 weeks, whereas the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines state that the optimal tapering regimen has not been established but suggest reducing the dose of corticosteroids over 8–12 weeks.6 80 Similar regimens have been employed for inducing remission in CD.6 13 The dose of corticosteroids can be adjusted according to disease severity and patient tolerance, but there is no evidence to suggest a benefit from doses greater than 60 mg prednisolone per day, the optimal starting dose may be 40 mg, smaller doses are probably inferior.4 It is also important to note that slow or very slow tapering regimes may be required for patients who have been on long-term steroids to avoid withdrawal side effects particularly if there is adrenocortical insufficiency as indicated by an abnormal short synacthen test.59

Loss of bone density may occur as a result of IBD even before diagnosis.81 Corticosteroids compound this problem, with between 17% and 41% of patients with IBD having osteoporosis.82 It is recommended that all patients with IBD taking corticosteroids should have 800–1000 mg of calcium and 80 IU of vitamin D per day, either through diet or oral supplementation. The BSG guidelines outline an algorithm for determining the risk of a fracture and recommend patients at high risk should also be started on a bisphosphonate.6

Corticosteroids stimulate gluconeogenesis within the liver and result in hyperglycaemia.83 Patients using oral corticosteroids are more than twice as likely to require hypoglycaemic therapy compared with non-users (RR 2.23, 95% CI 1.92 to 2.59).84 This may affect both patients with and without previous diabetes mellitus and all patients receiving courses of corticosteroids for longer than 3 months should have their glycaemic control monitored and be considered for hypoglycaemic therapy.

The association between corticosteroids and peptic ulcer disease remains controversial.25 In experimental models, corticosteroids impair ulcer healing,85 86 however, a meta-analysis found the risk of developing a peptic ulcer with corticosteroid use was similar to placebo.87 Therefore, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence does not recommend proton pump inhibitors as routine prophylaxis of peptic ulceration in people taking oral corticosteroids.88

Cataracts occur in almost one-third of patients on long-term corticosteroids.89 The risk appears to increase with both the dose and duration of steroid treatment, once again highlighting the importance of minimising corticosteroid dependency in IBD.90

Corticosteroids increase the risk of septicaemia, cellulitis, varicella, herpes zoster and scabies and patients are at particular risk of lower respiratory tract infections and candidiasis in the first weeks of treatment.41 Recent data also suggest that high-dose corticosteroids (≥40 mg prednisolone or equivalent per day) increase the risk hepatitis B reactivation, although this has not yet been studied in an IBD population. There is clear is evidence that high dose steroids are associated with worse outcomes with influenza infection and the same is suspected for CoronaVirus Infectious Disease-19.91–93

A discussion of the full range of side effects from corticosteroids is beyond the scope of this article, however, particular thought should be given to the risk of avascular necrosis of the femoral head, which presents with hip pain.94 If suspected, steroids should be discontinued immediately until an MRI has excluded the condition. Clinicians should also be aware that 5.7% of individuals using steroids experience severe psychiatric symptoms and should therefore screen for depression and the less common steroid-induced psychosis, which if present warrants corticosteroids withdrawal.95 96

Conclusion

Corticosteroids remain a potent tool in the expanding array of treatments for IBD in the 21st century, however, they need to be used carefully since their misuse can lead to challenging sometimes life-threatening side effects. Their use and misuse is a key performance indicator and a benchmark of the quality of an IBD service and should be regularly audited. The decision to initiate steroids should always be considered carefully and ideally wherever possible by an IBD MDT.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB wrote the manuscript. All coauthors contributed to editing, preparing and revising the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: JB is supported by a grant provided by Crohn's and Colitis UK (grant number: SP2018/3). CS has received unrestricted research grants from Warner Chilcott, Janssen and AbbVie, has provided consultancy to Warner Chilcott, Falk, AbbVie, Takeda, Fresenius Kabi and Janssen, and had speaker arrangements with Warner Chilcott, Falk, AbbVie, MSD, Pfizer and Takeda. TR has received research/educational grants and/or speaker/consultation fees from Abbvie, BMS, Celgene, Ferring, Gilead, GSK, LabGenius, Janssen, Mylan, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Takeda and UCB GCP has received unrestricted grants from AbbVie and Takeda, has provided consultancy for AbbVie, Ferring, Takeda, Napp Pharmaceuticals, Janssen and Tillotts and has speaker arrangements with Ferring, Takeda, Janssen, AbbVie and Falk. RP is supported by funding from Wellcome Trust Institute Strategic Support Fund (ISSF) and Crohn's and Colitis UK grant. He has provided consultancy/ or speakers fees for Napp Pharmaceuticals and Falk. He has had educational grants from Pharmacosmos, Abbvie, Janssen, Warner-Chilcottand Takeda.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Truel SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J 1955;2:1041–8. 10.1136/bmj.2.4947.1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones JH, Lennard-Jones JE. Corticosteroids and corticotrophin in the treatment of Crohn's disease. Gut 1966;7:181–7. 10.1136/gut.7.2.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Treadwell BL, Sever ED, Savage O, et al. Side-Effects of long-term treatment with corticosteroids and corticotrophin. Lancet 1964;1:1121–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(64)91804-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:590–9. 10.1038/ajg.2011.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Truelove SC, Watkinson G, Draper G. Comparison of corticosteroid and sulphasalazine therapy in ulcerative colitis. Br Med J 1962;2:1708–11. 10.1136/bmj.2.5321.1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019;68:s1–106. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wiles A, Bredin F, Chukualim B, et al. In the treatment of flares of inflammatory bowel disease, intravenous hydrocortisone causes greater falls in blood potassium and more severe episodes of hypokalaemia than methylprednisolone. Gut 2011;60:A223–4. 10.1136/gut.2011.239301.471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart AH, et al. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:103–10. 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lees CW, Heys D, Ho GT, et al. A retrospective analysis of the efficacy and safety of infliximab as rescue therapy in acute severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:411–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1841–5. 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zaghiyan K, Melmed GY, Berel D, et al. A prospective, randomized, noninferiority trial of steroid dosing after major colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2014;259:32–7. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318297adca [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Subramanian V, Saxena S, Kang J-Y, et al. Preoperative steroid use and risk of postoperative complications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing abdominal surgery. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:2373–81. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bar-Meir S, Chowers Y, Lavy A, et al. Budesonide versus prednisone in the treatment of active Crohn's disease. The Israeli budesonide Study Group. Gastroenterology 1998;115:835–40. 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70254-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management on behalf of ECCO. J Crohn’s Colitis 2016:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benchimol EI, Seow CH, Steinhart AH, et al. Traditional corticosteroids for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steinhart AH, Ewe K, Griffiths AM, et al. Corticosteroids for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003:CD000301. 10.1002/14651858.CD000301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lennard-Jones JE, Misiewicz JJ, Connell AM, et al. Prednisone as maintenance treatment for ulcerative colitis in remission. The Lancet 1965;285:188–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(65)90973-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chhaya V, Saxena S, Cecil E, et al. Steroid dependency and trends in prescribing for inflammatory bowel disease - a 20-year national population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:482–94. 10.1111/apt.13700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jakobsen C, Munkholm P, Paerregaard A, et al. Steroid dependency and pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in the era of immunomodulators--a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:1731–40. 10.1002/ibd.21559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Narula N, Borges L, Steinhart AH, et al. Trends in narcotic and corticosteroid prescriptions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the United States ambulatory care setting from 2003 to 2011. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:868–74. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Faubion WA, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, et al. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 2001;121:255–60. 10.1053/gast.2001.26279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Targownik LE, Nugent Z, Singh H, et al. Prevalence of and outcomes associated with corticosteroid prescription in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:622–30. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dorrington AM, Selinger CP, Parkes GC, et al. The historical role and contemporary use of corticosteroids in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2020:jjaa053. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waljee AK, Wiitala WL, Govani S, et al. Corticosteroid use and complications in a US inflammatory bowel disease cohort. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2013;9:30–25. 10.1186/1710-1492-9-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lewis JD, Scott FI, Brensinger CM, et al. Increased mortality rates with prolonged corticosteroid therapy when compared with antitumor necrosis Factor-α-Directed therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:405–17. 10.1038/ajg.2017.479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Melmed GY, Siegel CA, Spiegel BM, et al. Quality indicators for inflammatory bowel disease: development of process and outcome measures. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:662–8. 10.1097/mib.0b013e31828278a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, et al. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: special situations. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:63–101. 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. D'Haens GR, Panaccione R, Higgins PDR, et al. The London position statement of the world Congress of gastroenterology on biological therapy for IBD with the European Crohn's and colitis organization: when to start, when to stop, which drug to choose, and how to predict response? Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:199–212. 10.1038/ajg.2010.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Timmer A, Patton P, Chande N, et al. And 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis (review) summary of findings for the main comparison. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;18:CD00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chande N, Patton PH, Tsoulis DJ, et al. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease 2015;37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Selinger CP, Parkes GC, Bassi A, et al. A multi-centre audit of excess steroid use in 1176 patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:964–73. 10.1111/apt.14334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Filipe V, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Self-Medication with steroids in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2016;48:23–6. 10.1016/j.dld.2015.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jasim M, Pollok R. PWE-027 Self-medication with oral corticosteroids in amongst patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2018;67:A81. [Google Scholar]

- 35. IBD Registry 2018/19 . Annual report on the use of biologics for inflammatory bowel diseases. Available: https://ibdregistry.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Annual-Report-on-the-Use-of-Biologics-for-Inflammatory-Bowel-Diseases-2018-19-IBD-Registry-Oct-2019.pdf

- 36. RCP . UK IBD audit 2nd round report, 2008. Available: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/ibd-audit-round-two-2008-10

- 37. RCP . National report of the results of the UK IBD audit 3rd round inpatient experience questionnaire responses, 2012. Available: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/ibd-inpatient-care-audit-adult-report-round-three-2012

- 38. Guilcher K, Fournier N, Schoepfer A, et al. Change of treatment modalities over the last 10 years in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Switzerland. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;30:1159–67. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Juneja M, Baidoo L, Schwartz MB, et al. Geriatric inflammatory bowel disease: phenotypic presentation, treatment patterns, nutritional status, outcomes, and comorbidity. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:2408–15. 10.1007/s10620-012-2083-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Parian A, Ha CY. Older age and steroid use are associated with increasing polypharmacy and potential medication interactions among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:1–400. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fardet L, Petersen I, Nazareth I. Common infections in patients prescribed systemic glucocorticoids in primary care: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002024–20. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ananthakrishnan AN, Donaldson T, Lasch K, et al. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly patient: challenges and opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:882–93. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Probert CSJ, Dignass AU, Lindgren S, et al. Combined oral and rectal mesalazine for the treatment of mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis: rapid symptom resolution and improvements in quality of life. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:200–7. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marteau P, Probert CS, Lindgren S, et al. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalazine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut 2005;54:960–5. 10.1136/gut.2004.060103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Farup PG, Hovde O, Halvorsen FA, et al. Mesalazine suppositories versus hydrocortisone foam in patients with distal ulcerative colitis. A comparison of the efficacy and practicality of two topical treatment regimens. Scand J Gastroenterol 1995;30:164–70. 10.3109/00365529509093256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hartmann F, Stein J, BudMesa-Study Group . Clinical trial: controlled, open, randomized multicentre study comparing the effects of treatment on quality of life, safety and efficacy of budesonide or mesalazine enemas in active left-sided ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:368–76. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04354.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mulder CJ, Fockens P, Meijer JW, et al. Beclomethasone dipropionate (3 Mg) versus 5-aminosalicylic acid (2 G) versus the combination of both (3 mg/2 G) as retention enemas in active ulcerative proctitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996;8:549–54. 10.1097/00042737-199606000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kruis W, Neshta V, Pesegova M, et al. Budesonide suppositories are effective and safe for treating acute ulcerative proctitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:98–106. 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rubin DT, Sandborn WJ, Bosworth B, et al. Budesonide foam has a favorable safety profile for inducing remission in mild-to-moderate ulcerative proctitis or Proctosigmoiditis. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:3408–17. 10.1007/s10620-015-3868-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bar-Meir S, Fidder HH, Faszczyk M, et al. Budesonide foam vs. hydrocortisone acetate foam in the treatment of active ulcerative proctosigmoiditis. Dis Colon Rectum 2003;46:929–36. 10.1007/s10350-004-6687-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Narula N, Dhillon A, Zhang D, et al. Enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;4:CD000542. 10.1002/14651858.CD000542.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rezaie A, Kuenzig ME, Benchimol EI, et al. Budesonide for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD000296. 10.1002/14651858.CD000296.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sherlock ME, MacDonald JK, Griffiths AM, et al. Oral budesonide for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD007698. 10.1002/14651858.CD007698.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Manguso F, Bennato R, Lombardi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral beclomethasone dipropionate in ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0166455. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rutgeerts P, Löfberg R, Malchow H, et al. A comparison of budesonide with prednisolone for active Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 1994;331:842–5. 10.1056/NEJM199409293311304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, et al. Oral budesonide for active Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 1994;331:836–41. 10.1056/NEJM199409293311303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pollok RCG, Saxena S, Alexakis C, et al. Ibd 2017, Budenoside use is a key quality marker in the management of IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:E41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Irving PM, Gearry RB, Sparrow MP, et al. Review article: appropriate use of corticosteroids in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:313–29. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Long GH, Tatro AR, Oh YS, et al. Analysis of safety, medical resource utilization, and treatment costs by drug class for management of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States based on insurance claims data. Adv Ther 2019;36:3079–95. 10.1007/s12325-019-01095-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bierut A, Jesionowski M, Pruszko C, et al. Economic implications of budesonide MMX ® advantage in ulcerative colitis treatment over systemic steroids: budesonide MMX ® decreases ulcerative colitis treatment costs. Value in Health 2016;19:A314–5. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.03.983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Selinger CP, Parkes GC, Bassi A, et al. Assessment of steroid use as a key performance indicator in inflammatory bowel disease-analysis of data from 2385 UK patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;50:1009–18. 10.1111/apt.15497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Johnson SL, Bartels CM, Palta M, et al. Biological and steroid use in relationship to quality measures in older patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a US Medicare cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008597–8. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pearson D, May G, Fick GH, et al. Azathioprine for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ardizzone S, Maconi G, Russo A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of azathioprine and 5-aminosalicylic acid for treatment of steroid dependent ulcerative colitis. Gut 2006;55:47–53. 10.1136/gut.2005.068809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Barreiro-de Acosta M, Lorenzo A, Mera J, et al. Mucosal healing and steroid-sparing associated with infliximab for steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2009;3:271–6. 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2013;369:699–710. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Colombel J-F, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn's disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology 2007;132:52–65. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369:711–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1201–14. 10.1056/NEJMoa1900750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands B, et al. DOP76 corticosteroid sparing effects of ustekinumab therapy for ulcerative colitis through 2 years: UNIFI long-term extension. J Crohn’s Colitis 2020;14:S113–4. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1946–60. 10.1056/NEJMoa1602773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1723–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kapasi R, Glatter J, Lamb CA, et al. Consensus standards of healthcare for adults and children with inflammatory bowel disease in the UK. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019:flgastro-2019-101260. 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Barrett K, Saxena S, Pollok R. Using corticosteroids appropriately in inflammatory bowel disease: a guide for primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:497–8. 10.3399/bjgp18X699341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Inflammatory bowel disease toolkit. Available: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/ibd [Accessed January 17, 2020].

- 76. Joseph RM, Hunter AL, Ray DW, et al. Systemic glucocorticoid therapy and adrenal insufficiency in adults: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;46:133–41. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Broersen LHA, Pereira AM, Jørgensen JOL, et al. Adrenal insufficiency in corticosteroids use: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:2171–80. 10.1210/jc.2015-1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J Crohn’s Colitis 2017;11:769–84. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Fascì-Spurio F, Meucci G, Papi C, et al. The use of oral corticosteroids in inflammatory bowel diseases in Italy: an IG-IBD survey. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:1092–7. 10.1016/j.dld.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. Acg clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:384–413. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Agrawal M, Arora S, Li J, et al. Bone, inflammation, and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2011;9:251–7. 10.1007/s11914-011-0077-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ali T, Lam D, Bronze MS, et al. Osteoporosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Med 2009;122:599–604. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Exton JH. Regulation of gluconeogenesis by glucocorticoids. Monogr Endocrinol 1979;12:535–46. 10.1007/978-3-642-81265-1_28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gurwitz JH, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ, et al. Glucocorticoids and the risk for initiation of hypoglycemic therapy. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:97–101. 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420010131015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Luo JC, Shin VY, Liu ESL, et al. Non-ulcerogenic dose of dexamethasone delays gastric ulcer healing in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003;307:692–8. 10.1124/jpet.103.055202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Carpani de Kaski M, Rentsch R, Levi S, et al. Corticosteroids reduce regenerative repair of epithelium in experimental gastric ulcers. Gut 1995;37:613–6. 10.1136/gut.37.5.613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Conn HO, Poynard T. Corticosteroids and peptic ulcer: meta-analysis of adverse events during steroid therapy. J Intern Med 1994;236:619–32. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb00855.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. (NICE) TNI for CE . Clinical knowledge summary: corticosteroids, 2017. Available: https://cks.nice.org.uk/corticosteroids-oral#!scenario [Accessed March 2, 2020].

- 89. McDougall R, Sibley J, Haga M, et al. Outcome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving prednisone compared to matched controls. J Rheumatol 1994;21:1207–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Urban RC, Cotlier E. Corticosteroid-Induced cataracts. Surv Ophthalmol 1986;31:102–10. 10.1016/0039-6257(86)90077-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hatano M, Mimura T, Shimada A, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation with corticosteroid therapy in patients with adrenal insufficiency. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2019;2:e00071. 10.1002/edm2.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wong GL-H, Wong VW-S, Yuen BW-Y, et al. Risk of hepatitis B surface antigen seroreversion after corticosteroid treatment in patients with previous hepatitis B virus exposure. J Hepatol 2020;72:57–66. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kennedy N, Jones G, Lamb C. British Society of gastroenterology (Bsg) guidance for management of inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gut In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Chan KL, Mok CC. Glucocorticoid-Induced avascular bone necrosis: diagnosis and management. Open Orthop J 2012;6:449–57. 10.2174/1874325001206010449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lewis DA, Smith RE. Steroid-Induced psychiatric syndromes. A report of 14 cases and a review of the literature. J Affect Disord 1983;5:319–32. 10.1016/0165-0327(83)90022-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Brown ES, et al. Adverse consequences of glucocorticoid medication: psychological, cognitive, and behavioral effects. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:1045–51. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13091264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Murphy SJ, Wang L, Anderson LA, et al. Withdrawal of corticosteroids in inflammatory bowel disease patients after dependency periods ranging from 2 to 45 years: a proposed method. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:1078–86. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04136.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]