Significance

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) remains a major cause of severe respiratory disease worldwide in children, older individuals, and immunosuppressed patients. An increasing understanding of this disease burden together with the absence of an effective vaccine and limited therapeutic options has resulted in many new preclinical and clinical studies into novel vaccines, antibodies, and antivirals. This requires complementary expansion of the RSV molecular toolkit to encompass reverse genetics systems based on contemporary strains. We show that full-length cDNA clones of recent strains are most stable when a bacterial artificial chromosome is used as the vector backbone. This enabled recombinant viruses encoding antibody escape mutations to be generated and assessed with respect to antibody escape and capacity to induce cell-to-cell fusion.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, reverse genetics, escape mutants, cell-to-cell fusion

Abstract

Human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of acute lower respiratory infection in children under 5 y of age. In the absence of a safe and effective vaccine and with limited options for therapeutic interventions, uncontrolled epidemics of RSV occur annually worldwide. Existing RSV reverse genetics systems have been predominantly based on older laboratory-adapted strains such as A2 or Long. These strains are not representative of currently circulating genotypes and have a convoluted passage history, complicating their use in studies on molecular determinants of viral pathogenesis and intervention strategies. In this study, we have generated reverse genetics systems for clinical isolates of RSV-A (ON1, 0594 strain) and RSV-B (BA9, 9671 strain) in which the full-length complementary DNA (cDNA) copy of the viral antigenome is cloned into a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC). Additional recombinant (r) RSVs were rescued expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), mScarlet, or NanoLuc luciferase from an additional transcription unit inserted between the P and M genes. Mutations in antigenic site II of the F protein conferring escape from palivizumab neutralization (K272E, K272Q, S275L) were investigated using quantitative cell-fusion assays and rRSVs via the use of BAC recombineering protocols. These mutations enabled RSV-A and -B to escape palivizumab neutralization but had differential impacts on cell-to-cell fusion, as the S275L mutation resulted in an almost-complete ablation of syncytium formation. These reverse genetics systems will facilitate future cross-validation efficacy studies of novel RSV therapeutic intervention strategies and investigations into viral and host factors necessary for virus entry and cell-to-cell spread.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), also known as human orthopneumovirus, is the type species of the genus Orthopneumovirus in the family Pneumoviridae. RSV is the leading cause of acute lower respiratory infection in children under 5 y of age and is a major contributor to severe respiratory disease in older adults and immunosuppressed patients. Viral or bacterial coinfections are commonly observed in hospitalized children and are associated with an exacerbation of the disease (1, 2). After the successful worldwide introduction of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, RSV has recently been reported to be the major etiological cause of pneumonia in children under 5 y of age (3). Annual epidemics of RSV occur worldwide and are not only associated with high morbidity and mortality burdens but also with major economic costs. The increasing recognition of the challenges posed to society by RSV has spurred extensive research efforts into the development of effective vaccine and therapeutic intervention strategies such as the use of antibodies or antivirals (4, 5). Many of these strategies target the RSV F protein, a type I transmembrane protein which mediates fusion of the virion with cellular membranes (6). This is primarily due to the high degree of amino acid conservation observed between the F protein of RSV subtypes and strains (7), the critical role this protein has in the viral life cycle (8), and it representing a major target for neutralizing antibodies (9). The humanized monoclonal antibody palivizumab (MEDI-493; Synagis) remains the only approved specific therapeutic for RSV and functions via its binding to antigenic site II which is present on both the prefusion and postfusion forms of the F protein (10, 11). Several studies have characterized palivizumab escape mutants in hospitalized RSV patients which are located between amino acids 255 and 275 (12). However, little information is available regarding the fitness or transmissibility of these variant viruses.

Early studies investigating the worldwide prevalence of RSV showed that two subtypes, A and B, cocirculate worldwide (13, 14), displaying seasonal variation with respect to subtype and genotype prevalence (15). Data regarding differences in virulence of RSV-A and RSV-B subtypes in children are inconclusive (16), with studies reporting either more severe clinical disease in RSV-A or RSV-B cases or disease of equivalent severity (17, 18). In recent years, RSV-A and RSV-B genotypes with sequence duplications in the G gene (RSV-A, ON1; RSV-B, BA) have become predominant worldwide, presumably due to their selective advantage in virus transmission. The ON1 genotype contains a 72-nt duplication and the BA genotype contains a 60-nt duplication, both in the second hypervariable region in the C-terminal region of the G gene (19, 20). One functional study has reported that the duplicated sequence in the G protein of BA strains may serve to increase binding to host cells and thus confer an advantage with respect to virus entry (21). Understanding the mechanisms through which these sequence duplications confer viral fitness advantage requires the use of RSV reverse genetics systems and primary cell cultures. The latter is required as the G protein is essential for infection of ciliated epithelial cells (22–24) but dispensable for virus entry into transformed cell lines such as HEp-2 or Vero (25).

Major differences have been previously observed in the properties of RSV strains during propagation in cell culture, including syncytium size and phenotype, virus titers, and thermal stability (26–28). In general, RSV-A strains have been shown to attain higher titers in cell culture with increased plaque size in comparison with RSV-B strains (29). This has resulted in a preponderance of studies using older laboratory-adapted subtype A strains such as A2 or Long, which both present fewer technical challenges with respect to in vitro virus culture. In recent years, however, an increased use of clinical isolates in RSV studies has become apparent (28, 30) which minimizes the potential confounding factor of acquisition of mutations during prolonged passage in transformed cell lines (31).

Existing reverse genetics systems for RSV have been predominantly based on the laboratory-adapted A2 or Long strains which date from 1961 and 1956, respectively (32, 33), and may not be considered representative of the predominant genotypes currently circulating worldwide. These systems have used low-copy plasmids (34–37) with in some cases modifications made to consensus virus antigenome sequences to introduce unique restriction enzyme sites to facilitate cloning protocols (34, 35, 37). An alternative approach to minimize problems with sequence stability of genomic or antigenomic complementary DNA (cDNA) copies of RNA virus genomes is the use of a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) as a vector backbone (38, 39). This strategy has previously been used once for RSV to facilitate cloning of a hybrid RSV-A2 strain containing the F gene of the line 19 strain (40). Although these systems have proved invaluable in advancing our understanding of RSV molecular biology and pathogenesis, it is important to more rigorously examine well-documented RSV subtype and strain differences using panels of recombinant viruses based on currently circulating strains for which the consensus sequence of the parental virus of the patient has been determined. This approach has recently been used to construct reverse genetics systems for RSV-A and -B based on strains classified within the GA2 and BA genotypes, respectively, in which the pBluescript KS(+) phagemid vector was used as the vector backbone (41, 42). The use of a high-copy vector backbone in these studies contrasts with earlier reverse genetics systems, and the extent to which this strategy can be generalized and applied to other RSV strains without concomitant instability of cloned viral sequences is unknown. We have assessed the viability of this approach during the development of more stable reverse genetics systems for clinical isolates of RSV-A and -B strains belonging to the ON1 and BA genotypes, respectively, and have optimized cloning protocols and the choice of vector backbone to ensure increased stability of cloned RSV sequences. The availability of a comprehensive RSV molecular toolbox for the predominant currently circulating genotypes will enable more rapid assessment of viral molecular determinants underlying viral pathogenesis and escape from therapeutics, and provides a panel of tagged viruses useful for investigations of virus–host interactions.

Results

Generation of RSV Reverse Genetics Systems Based on Clinical Isolates.

A wild-type RSV-A strain (RSV-A-0594) and RSV-B strain (RSV-B-9671) were isolated on HEp-2 cells from throat swabs obtained from patients hospitalized with confirmed RSV infection. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on RNA isolated directly from clinical swabs resulting in the generation of a consensus sequence for RSV-A-0594 (GenBank accession no. MW582528) and RSV-B-9671 (GenBank accession no. MW582529). These sequences were found to be identical to consensus sequences generated via NGS of viral RNA isolated following passage on HEp-2 cells. Phylogenetic analysis showed that RSV-A-0594 and RSV-B-9671 belonged to the ON1 and BA9 genotypes, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), and contained previously characterized sequence duplications of 72 nt (ON1 genotype) and 60 nt (BA genotype) in the second hypervariable region of the G gene (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). RSV-B-9671 also contained a previously described two-amino acid deletion (proline, lysine) at positions 158 and 159 of the G protein, which is not present in original RSV-B BA genotype sequences or laboratory isolates of RSV-B (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The sequences of the leader and trailer regions were confirmed by 5′ and 3′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) and were found to be identical to previously determined RSV genome termini (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

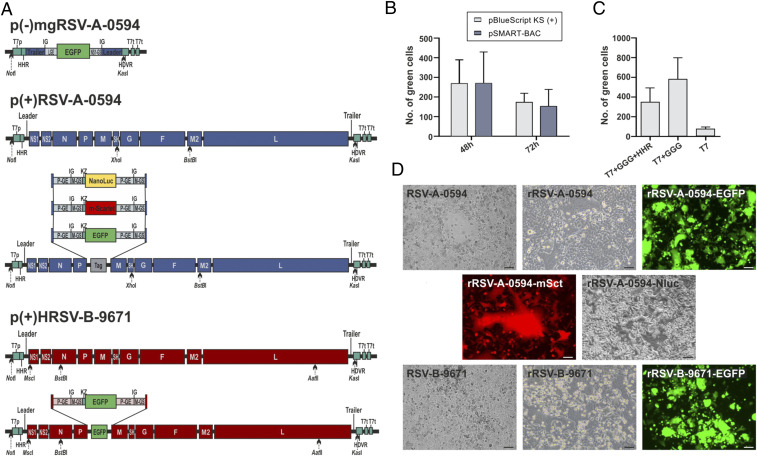

Assembly of a full-length RSV antigenome clone was initially attempted in the high-copy pBluescript II KS(+) phagemid vector. However, cloning procedures were technically challenging and time-consuming due to extreme instability of sequences in the region of the genome encoding the G protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Full-length clones with the correct consensus sequence were only obtained for RSV-B-9671 following prolonged growth of transformed bacteria (Stbl3; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at room temperature with increased concentrations of carbenicillin. Recombinant (r) RSV-B-9671 expressing either enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or the red fluorescent protein dTomato were successfully rescued in HEp-2 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). However, analogous cloning procedures for RSV-A-0594 resulted in clones containing full or partial deletions of the G gene. In order to enhance the stability of full-length RSV clones and increase the speed with which variant viruses could be generated, the full-length antigenome of RSV-B-9671 and partial antigenome of RSV-A-0594 were transferred from the pBluescript II KS(+) vector to pSMART-BAC (Fig. 1A). This resulted in enhanced sequence stability of pRSV-B-9671 and enabled construction of a stable full-length cDNA clone of RSV-A-0594 to be completed. No sequence mutations or deletions were observed in any BAC-based cDNA clone containing a full-length RSV-A or -B antigenome following growth in transformed bacteria. Comparison of both vector backbones in an RSV-A-0594 minigenome system showed no difference with respect to efficiency of minigenome rescue (Fig. 1B). Insertion of three guanine (G) residues following the T7 promoter significantly increased the efficiency of minigenome rescue, but the addition of a hammerhead ribozyme following these residues did not result in any further increase in minigenome rescue. rRSV-A-0594 and -B-9671 were rescued in HEp-2 cells with high efficiency with rescue events observed in all transfected wells. Codon optimization of N, P, M2-1, and L helper plasmids was not necessary for successful virus rescue. Additional rRSVs have also been rescued which stably express EGFP, mScarlet (mSct), or NanoLuc luciferase (Nluc) (Fig. 1 A and D).

Fig. 1.

Establishment of reverse genetics systems for clinical isolates of RSV ON1 and BA9 strains. (A) Schematic diagrams of a negative-sensed RSV minigenome expressing EGFP (blue; Top) [p(−)mgRSV-A-0594] with flanking NotI and KasI restriction sites used for cloning into pBluescript II KS(+) or pSMART-BAC and full-length cDNA clones of RSV-A-0594 (blue; Middle) or RSV-B-9671 (red; Bottom) antigenomes cloned into pSMART-BAC. Additional transcription units inserted between the P and M genes contain ORFs for EGFP (RSV-A and RSV-B), mScarlet (RSV-A), or Nano luciferase (RSV-A) which are flanked by M gene start and Kozak sequences (both 5′), and P gene end sequence (3′). Unique restriction sites are indicated along with essential 5′ (T7 promoter, hammerhead ribozyme) and 3′ (hepatitis delta ribozyme, T7 terminator) sequences. (B and C) Comparison of RSV-A-0594 minigenome replication in either pBluescript II KS(+) or pSMART-BAC vector backbones (B) or with 5′ flanking sequences consisting of 1) T7 promoter alone, 2) T7 promoter and GGG motif, or 3) T7 promoter, GGG motif, and a hammerhead ribozyme (C). Data represent the mean of the total number of green cells observed in three independent experiments. (D) Phase and fluorescence photomicrographs showing HEp-2 cells infected with nonrecombinant RSVs (P1 RSV-A-0594, P1 RSV-B-9671) and recombinant RSVs (P2 rRSV-A-0594, P3 rRSV-A-0594-EGFP, P1 rRSV-A-0594-mSct, P1 rRSV-A-0594-Nluc, P2 rRSV-B-9671, P3 rRSV-B-9671-EGFP). (Scale bars, 75 µm and RSV-A-0594-EGFP and RSV-B-9671-EGFP, 250 µm.)

Characterization of Rescued Viruses.

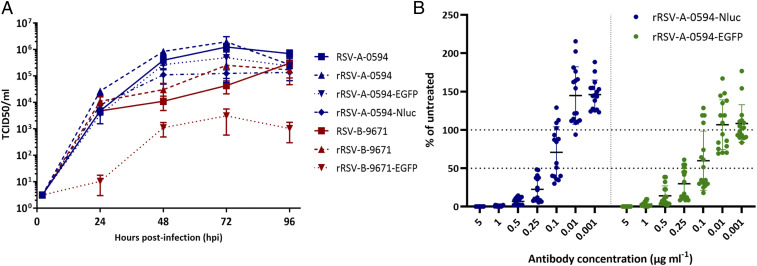

Comparison of the in vitro growth properties of RSV-A-0594 and RSV-B-9671 showed major differences with respect to plaque phenotype and growth kinetics. RSV-A-0594 induced large syncytium formation in HEp-2 cells, leading to complete fusion of the cell monolayer within 3 to 4 d postinfection (dpi) (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) with titers of ∼106 TCID50 (median tissue-culture infectious dose)/mL obtained (Fig. 2). In contrast, RSV-B-9671 infection resulted in smaller areas of cell-to-cell fusion (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) with the observed cytopathic effect (CPE) predominantly consisting of cell piling, rounding, and detachment. RSV-B-9671 infections progressed much slower with maximum CPE observed between 5 and 7 dpi. Virus titers of ∼105 TCID50/mL were obtained from RSV-B-9671–infected HEp-2 cell cultures. Analysis of consensus viral genome sequences generated following three passages in HEp-2 cells showed that RSV-A-0594 had acquired a single c>t nucleotide change at nucleotide 6026 leading to an amino acid change (P101S) in the F protein. Two synonymous substitutions in the P and F genes were detected in RSV-B-9671 following five passages in HEp-2 cells.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of recombinant viruses. (A) Multistep growth kinetics of nonrecombinant and recombinant RSV in HEp-2 cells. Cells were infected with nonrecombinant and recombinant RSV-A (blue symbols) or RSV-B (red symbols) at an MOI of 0.01 and wells were harvested at the indicated time points. Virus titers were determined by end-point dilution assay performed in triplicate at each time point with mean virus titers shown as log10 TCID50/mL. (B) Assessment of neutralization capacity of palivizumab on rRSV-A-0594-EGFP (green) and rRSV-A-0594-Nluc (blue). Virus was preincubated with the indicated palivizumab concentrations for 1 h and then added to HEp-2 cells in a 96-well plate (eight replicates for each palivizumab concentration). Infected wells were quantified after 72 h using either an ELISpot reader (EGFP) or NanoGlo assay (Nluc). Data are expressed as the percentage of average luciferase/ELISpot readings compared with untreated infected control wells.

The phenotype of rescued rRSVs mirrored that of the parental virus strains during growth in HEp-2 cells with rRSV-A-0594 strains consistently displaying increased cell-to-cell fusion and maximal virus titers in comparison with rRSV-B-9671 strains (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). No significant differences were observed in the kinetics of virus replication between parental and recombinant RSV-A-0594 strains. Although nonrecombinant and recombinant RSV-B-9671 displayed similar growth kinetics, virus titers from rRSV-B-9671-EGFP infections were consistently lower by 1 to 2 log. Complete genome coverage was obtained by NGS for all recombinant RSV-A virus stocks, whereas Sanger sequencing had to be used to fill gaps in partial consensus sequences derived by NGS of recombinant RSV-B–infected HEp-2 cells (SI Appendix, Table S1). No sequence changes were detected in rRSV-A-0594 or rRSV-A-0594-EGFP following three passages in HEp-2 cells. Sequence analysis of rRSV-B-9671 and rRSV-B-9671-EGFP following four passages in HEp-2 cells showed a 2-nt insertion in the P gene end (nucleotides 3148 and 3149) and no sequence changes, respectively (SI Appendix, Table S1). All recombinant RSVs expressing fluorescent proteins were found to be stable during passage with no syncytia observed which were not fluorescent when viewed using ultraviolet (UV) microscopy. The utility of using wild-type rRSVs expressing EGFP or Nluc to perform rapid and sensitive RSV microneutralization assays was assessed using the humanized monoclonal antibody palivizumab, which binds to amino acids 254 to 277 (antigenic site II) of the RSV F protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (10, 43). In general, microneutralization data obtained with both viruses were comparable with 50% neutralization evident between 0.25 and 0.1 µg/mL palivizumab. Enhancement of infection at the lowest tested palivizumab concentrations of 0.01 and 0.001 µg/mL was especially pronounced in wells containing rRSV-A-0594-Nluc, which may be due to the enhanced sensitivity of Nluc in comparison with EGFP.

Recombineering Enables Rapid Generation of Recombinant RSVs with Palivizumab Escape Mutations.

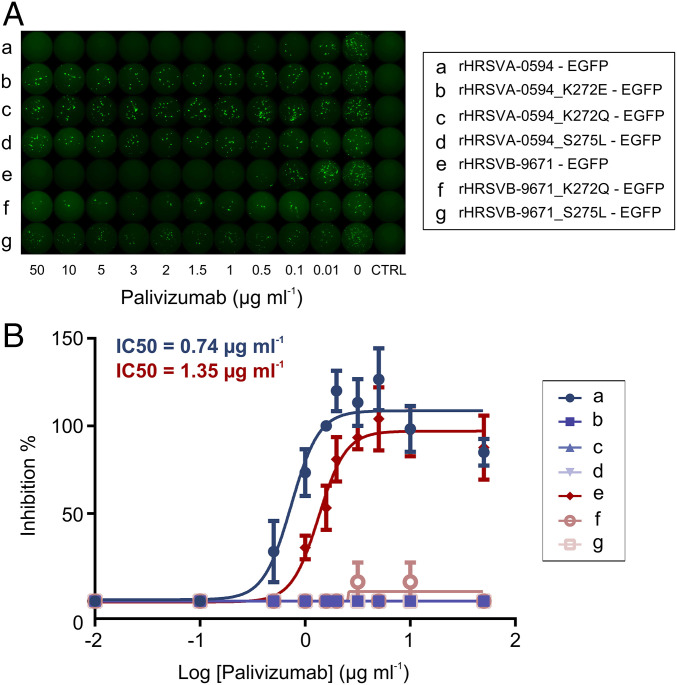

A major advantage of the use of a BAC as the vector backbone for cloning a full-length RSV antigenome is the opportunity to modify the virus genome directly via recombineering technologies. This enabled the generation of a panel of full-length clones of RSV-A-0594-EGFP and rRSV-B-9671-EGFP containing three F protein mutations (K272E, K272Q, S275L) that have been previously reported to lead to escape of RSV from neutralization by palivizumab (MEDI-493; Synagis) (SI Appendix, Table S2). All rRSV escape mutants were successfully rescued in HEp-2 cells and following primary rescue were cultured in media containing palivizumab to maintain stability of the specific F protein mutations. The growth of these rRSVs mirrored that of the unmodified rRSVs with RSV-A-0594 escape mutants spreading more rapidly and attaining higher titers than equivalent RSV-B-9671 escape mutants (SI Appendix, Table S9). Sequence analysis of rescued escape mutants showed no changes from the expected consensus sequences, except for a single amino acid change (A2014E) in the C-terminal region of the L protein of rRSV-B-9671-EGFPS275L and insertion of a single adenine residue following at nucleotide position 6351 in the genome of rRSV-B-9671-EGFPK272E. The latter mutation resulted in a premature stop codon, leading to a G protein truncated by 90 amino acids (SI Appendix, Table S1). This virus was not used in subsequent experiments due to the presence of a truncated G protein and an inability to generate virus stocks of sufficient titer (SI Appendix, Table S9). The ability of palivizumab to neutralize recent clinical isolates of RSV and complementary escape mutants was first assessed using a microneutralization assay (Fig. 3A). Testing of a range of palivizumab concentrations resulted in a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.73 µg/mL against RSV-A-0594-EGFP and 1.35 µg/mL against RSV-B-9671-EGFP (Fig. 3B). The five RSV-A and -B escape mutants escaped neutralization by all concentrations of palivizumab assessed in this assay. However, the number of foci of infection in wells containing escape mutants across all palivizumab concentrations was consistently half of the number of foci of infection observed in control wells in which no palivizumab was present.

Fig. 3.

Effective escape of palivizumab neutralizing activity by recombinant RSV escape mutants. (A) Representation of the microneutralization assay for rRSV-A-0594-EGFP and rRSV-B-9671-EGFP, each virus at different concentrations of palivizumab. Fluorescent plaques were indicative of positive virus infection. Fluorescence readout and well pictures were taken with an ELISpot device. (B) Dose–response curve of neutralizing activity of palivizumab in tested viruses by microneutralization assay. Neutralization (inhibition of infection) of evaluated wild-type viruses was achieved at an IC50 value of 0.74 µg/mL for rRSV-A-0594-EGFP and 1.35 µg/mL for rRSV-B-9671-EGFP. No neutralization of escape mutants was observed at any concentration of palivizumab. Three independent experiments were performed, error bars represent SEM.

Impact of Palivizumab Escape Mutations on RSV Cell-to-Cell Fusion.

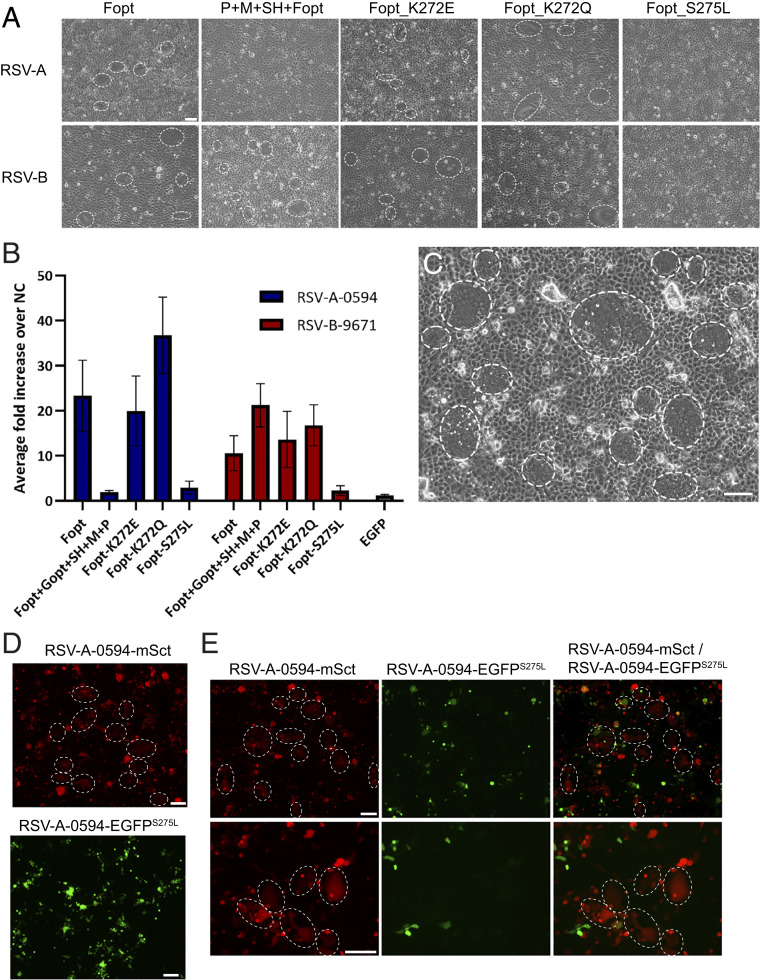

The same palivizumab escape mutations in the F protein (K272E, K272Q, S275L) examined previously in the context of recombinant viruses were also examined for their impact on virus-induced cell-to-cell fusion. This necessitated the establishment of a quantitative cell-fusion assay for wild-type RSV strains based on the reconstitution of the alpha- and omega-fragments of split β-galactosidase upon cell-to-cell fusion. We first confirmed that macroscopic cell fusion was visible upon transfection of Vero cells with a plasmid vector expressing codon-optimized (opt) RSV-A2 F protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). However, initial attempts to establish analogous fusion assays with RSV-A-0594 or RSV-B-9671 Fopt proteins in Vero, HEp-2, or 293T cells were unsuccessful with respect to generation of macroscopically visible syncytia. Further optimization of transfection protocols was performed including pretreatment of Vero cells with hydroxychloroquine and mixing of the two transfected Vero cell populations only 1 h following transfection. Collectively, these modifications resulted in consistent syncytium formation in Vero cells transfected with plasmids expressing RSV-A-0594 or RSV-B-9671 Fopt protein (Fig. 4A). Quantification of these fusion assays showed that RSV-A-0594 F protein induced higher levels of cell-to-cell fusion than RSV-B-9671 F protein (Fig. 4B). However, this level of fusion activity was approximately six times less than that induced by RSV-A2 F protein. An increase in the amount of RSV-A-0594 F protein used in transfections from 1.5 to 5 µg greatly enhanced syncytium formation (Fig. 4C). Expression of additional RSV proteins including P, M, SH, and G has previously been shown to enhance F protein-induced cell-to-cell fusion (44–46) or to be required for filament formation on the surface of infected cells (47). We observed conflicting results with this strategy. Cotransfection of additional vectors expressing RSV proteins including P, M, SH, and G inhibited RSV-A-0594 F protein-induced cell-to-cell fusion but conversely enhanced cell fusion induced by RSV-B-9671 F protein (Fig. 4 A and B). The establishment of a functional fusion assay using RSV F proteins derived from clinical isolates also enabled a comparison of RSV F proteins containing palivizumab escape mutations. A consistent pattern of results was obtained for both RSV-A-0594 and RSV-B-9671 F protein mutants. The cell fusion induced by RSV F proteins with a K272E mutation was similar to that of the unmodified F proteins, but modification of this residue to K272Q resulted in a significant enhancement in cell fusion. In contrast, the presence of S275L in the F protein of both RSV subtypes significantly reduced the levels of cell-to-cell fusion (Fig. 4 A and B). We confirmed this hypofusogenic phenotype conferred by the S275L mutation in the context of virus infections by comparing the cell fusion induced during individual and coinfections of rRSV-A-0594-mSct and RSV-A-0594-EGFPS275L in HEp-2 cells. As expected, rRSV-A-0594-mSct induced large syncytia whereas RSV-A-0594-EGFPS275L induced minimal levels of cell-to-cell fusion (Fig. 4 D and E). However, reduced levels of cell-to-cell fusion did not have an impact on virus replication and release as virus titers obtained for RSV-A-0594-EGFPS275L were comparable to or higher than those obtained from analogous RSV-A-0594-EGFP infections (SI Appendix, Table S9).

Fig. 4.

Assessment of the impact of palivizumab escape mutations on RSV cell-to-cell fusion. (A) Photomicrographs of cell-fusion assays imaged 48 h posttransfection of Vero cells with pCG vectors expressing RSV-A-0594 or RSV-B-9671 Fopt, P + M + G + Fopt, Fopt_K272E, Fopt_K272Q, and Fopt_S275L. (Scale bar, 75 µm.) (B) Quantification of cell-to-cell fusion observed 48 h postmixing of Vero cell populations transfected with a plasmid expressing β-galactosidase alpha-fragment alone or cotransfected with the indicated RSV expression plasmids and β-galactosidase alpha-fragment in transfected Vero cells. Enzymatic activity of reconstituted β-galactosidase was measured using a Tecan Infinite 200 plate reader. Data are shown as fold increase over negative control (NC) and represent the average of eight replicates performed in each of three independent experiments. NC: Vero cells transfected with 1 µg of the β-galactosidase alpha-fragment alone were mixed with Vero cells cotransfected with 1 µg of the β-galactosidase omega-fragment. (C) Photomicrograph of enhanced cell-to-cell fusion observed 48 h posttransfection of Vero cells with 5 µg pCG-RSV-A-0594-Fopt. (Scale bar, 75 µm.) (D) Fluorescence photomicrographs of HEp-2 cells infected for 48 h with rRSV-A-0594-mSct (red) or rRSV-A-0594-EGFPS275L (green) (MOI of 0.01). (E) Fluorescence photomicrographs of HEp-2 cells coinfected for 48 h with rRSV-A-0594-mSct (red) and rRSV-A-0594-EGFPS275L (green) (MOI of 0.01). (D and E) Syncytia are indicated by dashed ellipses. (Scale bars, 150 µm.)

Discussion

Research into RSV has faced many technical challenges since the initial discovery of this virus in October 1955 following an outbreak of an acute respiratory disease in a chimpanzee colony (48). These include the necessity for stabilization of virus stocks (49), large variation in growth and plaque phenotype of wild-type strains upon isolation (27, 28), lack of an animal model that fully recapitulates the disease observed in humans (50), difficulties with viral glycoprotein expression (51, 52), and instability of cloned RSV sequences in standard plasmid vectors (40). In this study, we have attempted to moderate some of these impediments to research by generating stable reverse genetics systems for representative strains of the currently predominant RSV ON1 and BA genotypes and characterizing individual palivizumab escape mutations in the context of quantitative cell-fusion assays and recombinant viruses.

The high-copy phagemid vector pBluescript has been previously reported to be a suitable vector for construction of full-length cDNA clones for rhabdoviruses and paramyxoviruses (53–55) and also RSV strains belonging to the GA1 and BA genotypes (41, 42). In contrast, we have found that use of pBluescript KS(+) as a vector backbone for full-length cDNA clones consistently results in full or partial deletions of the G gene of both RSV-A and -B strains. The presence of a 72-nt duplicated sequence region in the G gene of an ON1 strain such as RSV-A-0594 may have increased inherent sequence instability issues in the context of a full-length clone in this vector. Instability of cloned RSV sequences has also been noted by Hotard and colleagues upon cloning of nucleotides 5382 to 9949 of pSynkRSV-line19F into the high-copy pMA vector (40). Therefore, future use of pBluescript as a vector backbone for the generation of pneumovirus reverse genetics systems is not recommended. In contrast, pSMART-BAC provided a more stable platform with which to construct RSV reverse genetics systems and proved amenable to the insertion of specific antibody escape mutations in full-length clones via the use of recombineering protocols or the insertion of additional open reading frames (ORFs) encoding fluorescent or luminescent proteins using HiFi DNA assembly protocols. Although a BAC-based reverse genetics system has been used previously to generate a recombinant A2 strain containing the F gene from the line 19 strain (40), the extension of BAC-based cloning protocols to clinical RSV isolates offers new opportunities to better model authentic virus–host interactions.

Observed variation in plaque phenotype and titers of wild-type RSV strains following isolation in vitro and characterization of phenotypic differences with older prototypic RSV strains are topics of increasing interest in contemporary RSV research (27, 28, 30, 56). Although few studies have systemically compared the in vitro growth of prototypic RSV-A and -B strains, it is well-established that the prototypic A2 or Long strains of RSV-A grow to higher titers and are more fusogenic than prototypic RSV-B strains such as B1 or CH-18537 (28, 29, 57). These observations are also replicated in studies performed using clinical isolates in which RSV-A strains produced significantly larger plaques and grew to higher titers than RSV-B strains upon isolation from patient samples (27, 58). Similarly, we observed large differences in the growth of clinical isolates of RSV-A and -B strains in HEp-2 cells, with RSV-A-0594 attaining maximum virus titers 1 to 2 log higher than RSV-B-9671. More rapid and larger syncytium formation and associated cytopathogenicity were also observed in RSV-A-0594–infected cell cultures. The molecular determinants underlying these phenotypic differences between RSV subtypes are unknown, but it can be assumed that the F protein has a major role given the primary role of this protein in mediating cell-to-cell fusion (8). A previous study has shown that a recombinant RSV-A2 strain containing an F protein based on a consensus sequence of the BA genotype generates reduced levels of cell-to-cell fusion in tissue-culture cells (59). The availability of stable reverse genetics systems for both subtypes will now enable a more precise delineation of which domains and specific amino acids of the F protein are responsible for such phenotypic strain differences.

Cell-fusion assays can also contribute to better understanding the role of individual viral proteins and specific amino acids in the development of multinucleated syncytia. We have therefore attempted to extend a quantitative cell-fusion assay based on expression of the laboratory-adapted RSV-A2 F protein to establish analogous assays for clinical isolates of RSV-A and -B. In contrast to RSV-A2 Fopt, which induced formation of large syncytia in transfected Vero cells, RSV-A-0594 Fopt and RSV-B-9671 Fopt displayed a hypofusogenic phenotype in transfected cells. However, higher levels of cell-to-cell fusion were observed by transfecting greater amounts of the plasmid expressing RSV-A-0594 F protein, resulting in syncytia more akin to that observed during virus infection. This suggests that the hypofusogenic phenotype observed following expression of RSV-A F proteins with an authentic wild-type sequence may be more reflective of protein expression issues rather than the intrinsic fusion capacity observed when F protein is produced in the context of a real virus infection. Interestingly, phenotypic differences were observed between RSV-A and -B with respect to induction of cell fusion. In contrast to RSV-A-0594, increasing the amount of transfected RSV-B-9671 F protein did not result in higher levels of cell-to-cell fusion. However, enhanced levels of cell fusion were observed when the RSV-B-9671 F protein was cotransfected with P, M, SH, and codon-optimized G protein. Cotransfection of RSV-A2 F protein with SH and G proteins has previously been shown to enhance cell-to-cell fusion (44–46) and P and M proteins have a critical role in mediating RSV filament formation (47) which is assumed to facilitate virus spread between cells. Further work is required to delineate the minimal protein constellation required to induce maximal RSV-B-9671 cell fusion. Comparative assessment of RSV-A-0594 or RSV-B-9671 F proteins with or without palivizumab escape mutations in antigenic site II showed that whereas K272E and K272Q mutations did not have an impact on cell fusion, S275L almost completely ablated cell-to-cell fusion. We confirmed this observation in the context of virus infection by examining the cytopathic effects induced by rRSV-A-0594-EGFPS275L in a single infection or in the context of a coinfection with rRSV-A-0594-mSct. A previous study by Zhu et al. (60) has also examined the K272E, K272Q, and S275L mutations in the context of virus infection by inserting these mutations into a recombinant RSV-A2. In this study, no impact on plaque size was noted, although given that the cDNA clone used to generate these viruses has a total of 19 nucleotide differences from the original RSV-A2 clone (61), it is not clear if the F protein of this virus has a hyper- or hypofusogenic phenotype in cell culture.

The use of clinical isolates in research on virus–host interactions or virus pathogenesis has increased in recent years primarily to minimize the potential confounding factor of such mutations acquired during in vitro passage or inserted to facilitate cloning procedures (61–64). It is therefore also important to retrospectively better understand how sequence variation in older laboratory-adapted isolates such as A2 or Long contributes to well-characterized RSV strain differences. Sequence analysis has previously shown that higher-passage RSV-A2 has two amino acid substitutions in the F protein (E66K and P101Q) in comparison with an early-passage A2 strain which had been passaged seven times in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells (RSV-A2 HEK7) following primary isolation (31, 65, 66). These amino acid changes are not present in the RSV-A-0594 or RSV-B-9671 F proteins and have been shown to confer a hyperfusogenic phenotype in the context of recombinant viruses and cell-fusion assays (67, 68). Sequence analysis of the RSV-A2 F protein used in this study (GenBank accession no. MW582527) and review of an almost-complete genome sequence of RSV-A2 (ATCC VR-1540) (69) confirm the presence of E66K and P101Q mutations in the F protein and one additional amino acid change in the G protein (E14D) in comparison with the full-genome sequence of RSV-A2 HEK7 (65). The possibility that additional amino acid changes were acquired during earlier passages of RSV-A2 in HEK cells will remain unknown in the absence of additional sequence data. The F protein of the commonly used Long strain also displays variation at codon 101 between different laboratory isolates with proline, threonine, and serine (GenBank sequence ID codes M22643, AY911262, and KF713490) all reported at this position. Similarly, sequence analysis performed in this study revealed a single amino acid change (P101S) in the F protein of a passage 3 stock of nonrecombinant RSV-A-0594. This suggests that amino acid changes in the F protein of clinical isolates can be rapidly selected during in vitro passage and confirms the value of basing new reverse genetics systems on consensus virus sequences obtained directly from patient samples.

Moving forward, a more precise delineation of the underlying molecular determinants governing RSV strain variation will be essential to better understand the dichotomy between large variations observed between growth of RSV strains in in vitro and in vivo models (70, 71) with the few confirmed differences in clinical disease induced by RSV strains in patients (72). This will rely on an increased range of reverse genetics systems based on clinical isolates which can now be rapidly assembled in BACs and readily manipulated via the use of recombineering protocols. The recently reported rapid assembly of a full-length RSV-B antigenome sequence in a yeast artificial chromosome vector via the use of transformation-associated recombination cloning (73) provides an additional complementary pathway toward these goals. In summary, the reverse genetics systems outlined in this study build upon previous advances made for prototypic RSV strains such as A2 and Long and pave the way for a more systematic analysis of molecular determinants underlying subtype and strain variation and comparative assessment of fitness of naturally occurring antibody or antiviral escape mutants.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Viruses.

HEp-2 and Vero cells were cultured in advanced minimum essential medium, whereas 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. Media for culture of Vero and 293T cells were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 10270106), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% GlutaMAX. HEp-2 cell media were supplemented with 5% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 26140079), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% GlutaMAX. Cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Wild-type RSV strains were isolated on HEp-2 cells from clinical swab samples obtained from patients at Hannover Medical School during the 2014 to 2015 winter season; RSV-A-0594 was isolated from a fatal case in a 6-mo-old child with severe combined immunodeficiency, and RSV-B-9671 was isolated from a 2-y-old child with a nonfatal disease course. Laboratory-adapted RSV-A2 strain was obtained from ATCC (VR-1540). All nonrecombinant and recombinant RSVs were grown in HEp-2 cells in Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Virus stocks were harvested by scraping the infected cells into supernatant, centrifuging at 400 × g for 5 min, followed by removal of supernatant to a separate tube containing an equivalent volume of stabilization solution for a final concentration of 32% glycerol, 10% FBS. Additional cell-associated virus was obtained by resuspending the cell pellet in 3 mL Opti-MEM and performing two rapid freeze–thaw cycles by snap freezing in liquid nitrogen. Following centrifugation at 400 × g for 5 min, the 3 mL supernatant containing released cell-associated virus was added to the stabilized supernatant fraction, and virus stocks were aliquoted into cryovials for long-term storage at −150 °C. Viral titers were determined by end-point dilution assays (TCID50). Serial dilutions of virus stock were added to 90% confluent HEp-2 cells in 96-well plates and incubated for 5 d with the presence of infected cells in individual wells determined using UV microscopy for rRSVs expressing fluorescent proteins and by use of a modified immunostaining protocol (74) for nonfluorescent RSVs. In brief, cells were washed three times with 200 µL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), permeabilized with 100 µL 0.5% Triton-X/PBS for 10 min, and then blocked with 100 µL 5% milk in PBS for 1 h. Blocking solution was removed and 50 µL primary antibody (Abcam; anti-RSV; ab20745; 1:800) in 5% milk in PBS was applied to each well, incubated for 1 h, and washed three times with PBS; 100 µL secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific; AF 488 donkey anti-goat; A32814; 1:400) in 5% milk was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 1 h before cells were washed five times with 200 µL PBS, and infected wells were counted using UV microscopy. TCID50/mL was calculated using the Spearman–Kärber calculation (75). Modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing T7 RNA polymerase (MVA-T7), kindly provided by Gerd Sutter, Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, Munich, Germany, was propagated in chicken embryo fibroblasts and titrated in BHK-21 cells to determine TCID50/mL.

Multistep Growth Curve Analysis.

HEp-2 cells grown to 80% confluency on 12-well plates (Sarstedt) were infected in triplicate with each virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 for 2 h, and then washed five times with Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS) (with calcium and magnesium; Thermo Fisher Scientific). After removal of the last DPBS wash, 700 µL Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1% GlutaMAX was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Three wells infected with each virus were immediately harvested as described previously (0 h) and frozen at −150 °C, with subsequent time points collected in triplicate at 24, 48, and 72 h and 96 h postinfection. Virus titers for each time point were determined using TCID50 in 96-well plates, using the Spearman–Kärber calculation (75).

Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analyses.

Sequencing of nonrecombinant and recombinant RSVs was performed using next-generation sequencing. Briefly, libraries were generated using MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 or NextSeq 500/550 High Output Kit v2.5 and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq System (300 cycles, paired-end) or Illumina NextSeq System (150 cycles, paired-end), respectively. Raw sequence datasets were analyzed with respect to quality control and assembled to the reference RSV-A-0594 strain and RSV-B-9671 using CLC Genomics Workbench 9.0 (QIAGEN). Primer sets designed to cover the genomes of RSV-A-0594 and RSV-B-9671 (SI Appendix, Table S8) were used in Sanger sequencing (Eurofins Genomics or Microsynth Seqlab) of RSV expression plasmids, full-length cDNA clones, and gap filling of partial consensus sequences of recombinant RSV-B strains which had been generated using NGS. Specific primers (SI Appendix, Table S3) were used to confirm genome terminus sequences using 5′ and 3′ RACE protocols as previously described (76). Consensus sequences obtained from RSV-A-0594 and RSV-B-9671 were aligned with full-length RSV genome sequences which had been retrieved from GenBank using MAFFT v7 (77). Phylogenetic relationships of RSV-A and -B strains based on complete genome sequences and the second hypervariable region of the G gene, respectively, were assessed by the maximum-likelihood method using IQ-TREE (78). The best-fit model of nucleotide substitution for both phylogenetic trees was determined by ModelFinder (79), which is implemented in IQ-TREE.

Plasmid Constructs.

Rescue of RSV Minigenomes and Recombinant Viruses.

For rescue of RSV minigenomes, HEp-2 cells were grown to 90% confluency in 96-well trays and infected with MVA-T7 at an MOI of between 2 and 2.5 for 30 min at 37 °C. Next, a pBluescript KS(+) or pSMART-BAC vector (1.6 μg) containing a negative-sensed RSV-A-0594 minigenome (flanked by either a T7 promoter, T7 promoter + GGG, or T7 promoter + GGG + hammerhead ribozyme) together with helper plasmids (pCG vector) expressing the RSV-A-0594 N (1.6 μg), P (1.2 μg), M2-1 (0.8 μg), and L (0.4 μg) proteins were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 diluted in Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After 12 to 24 h, media were replaced with growth media containing 2% FBS. Each combination of plasmids was replicated in three columns of a 96-well tray and independently repeated three times with readout performed at 48 h posttransfection in an ELISpot device (CTL; ImmunoSpot S6 Ultimate) with automatic counting of fluorescent spots.

For rescue of recombinant RSVs, HEp-2 cells were grown to 75% confluency in 6-well trays and infected with MVA-T7 as described above for RSV minigenomes. Cells were then transfected using pBluescript KS(+) (1.6 μg) containing a full-length cDNA copy of the RSV-B-9671 antigenome with RSV-B-9671 helper plasmids cloned into the pCG vector, or pSMART-BAC vector (1.6 μg) containing a full-length cDNA copy of the RSV-A-0594 or RSV-B-9671 antigenome together with their respective subtype-specific helper plasmids cloned into pCG or pcDNA3.1 vectors used at the same concentrations outlined above for minigenome rescue. On day 3 posttransfection, uninfected HEp-2 cells were added to each rescue well if required. Thereafter, cells were monitored for spreading foci of fluorescent cells or syncytium formation. In general, rRSV-A-0594 rescue wells were harvested at 5 to 6 d posttransfection (dpt) with detachment of cells into the supernatant performed using a cell scraper. One milliliter of this cell suspension was used to infect a T25 flask of HEp-2 cells with virus stocks harvested and stabilized 3 to 4 d later (passage 0). Individual rRSV-B-9671 rescue wells were in general trypsinized at 8 to 10 dpt and subsequently blind passaged three times (passage 0, 6 well>T25; passage 1, T25>T75; passage 2, T75>T75) with supplementation of new HEp-2 cells when required. Virus stocks were harvested and stabilized at passage 2, ∼3 wk after the initial transfection of rescue wells. Rescues of EGFP-, NanoLuc luciferase-, and mScarlet-expressing rRSVs were performed as described above for unmodified rRSV-A-0594 and rRSV-B-9671.

Cell-to-Cell Fusion Assay.

RSV cell-to-cell fusion was evaluated in Vero cells using a split β-galactosidase cell-fusion assay as previously described (76) with minor modifications. Plasmids expressing β-galactosidase alpha- and omega-fragments were kindly provided by Imke Steffen, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover. Vero cells were transfected using the Lipofectamine 3000 protocol after a 1-h preincubation with Opti-MEM containing 0.025 mM hydroxychloroquine. Either 1 µg of a plasmid expressing the β-galactosidase omega-fragment alone or 1 µg of a plasmid expressing the β-galactosidase alpha-fragment together with 1.5 µg of one or more plasmids expressing RSV proteins was transfected into Vero cells in a 6-well tray. After 1 h of incubation with transfection mixes, cells were washed repeatedly, trypsinized, and seeded into 96-well plates in Opti-MEM containing 2% FBS. In each well, a 100-µL suspension of cells cotransfected with omega-fragment/RSV-expressing plasmids was mixed with a 100-µL suspension of cells transfected only with alpha-fragment. As a negative control, cells transfected only with alpha-fragment were seeded together with cells transfected with only omega-fragment. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell-to-cell fusion was evaluated using a Galacto-Star Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Enzyme activity was measured using a Tecan Infinite 200 plate reader.

Microneutralization Assay.

Escape efficiency from palivizumab-mediated neutralization of generated escape mutants carrying the individual amino acid changes K272E, K272Q, and S275L in the F protein of both rRSV-A-0594-EGFP and rRSV-B-9671-EGFP was evaluated by microneutralization assay as previously described (60, 80) with modifications. Briefly, 100 TCID50 of virus was mixed with different concentrations of palivizumab in replicates of eight, incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, and added to a 95% confluent monolayer of HEp-2 cells in a 96-well plate. Fluorescence readout was performed after 72 h at a wavelength of 488 nm in an ELISpot device. Three independent replicates of these experiments were performed. Virus infection was detected by the presence of fluorescent plaques (infected cells), which indicated that no neutralizing activity was generated by palivizumab. Wells with one or more fluorescent plaques were assigned as positive, whereas wells with no fluorescent plaques were assigned as negative. Percentage of inhibition was calculated from the number of negative wells at each concentration of palivizumab. IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism v6 software.

To determine the utility of rRSV-A-0594-Nluc and rRSV-A-0594-EGFP, a microneutralization assay using rRSV-A-0594 with stable expression of NanoLuc luciferase (Promega) in parallel with rRSV-A-0594-EGFP was performed as described above, with the one minor modification of using 700 TCID50 per well of rRSV. The readout for the EGFP variant was done with an ELISpot reader and, for NanoLuc-expressing virus, the Promega NanoGlo Luciferase Assay System was used. In brief, infections with dilutions of palivizumab were set up as described above. rRSV-A-0594-Nluc–infected cells were lysed after 72 h using Promega Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis 5X Reagent (diluted 1:5 in nuclease-free H2O; Invitrogen), diluted again 1:10 in PBS (Gibco), and then mixed with NanoGlo substrate mix according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Virus infection was detected by a Tecan Infinite Pro-200 luminescence reader.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Erhard van der Vries for useful discussions during the initiation of this project and acknowledge Mareike Schubert and Ilka Baumann for technical assistance. We also thank the Genomics Lab at the Institute of Animal Breeding and Genetics, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, and the NGS core facility at the Hannover Medical School for operation of the Illumina MiSeq and NextSeq systems. This study was supported by grants from the Niedersachsen-Research Network on Neuroinfectiology (N-RENNT) from the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony, Germany, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—398066876/GRK 2485/1, and the R2N Project funded by the Federal State of Lower Saxony, Germany. Part of this work was funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation within the framework of the Alexander von Humboldt Professorship endowed by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and also received funding from the Eurostars-2 joint programme with cofunding from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (VICTORIOUS, Reference No. 11593).

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: A patent application (PCT/EP2019/054775) entitled “Improved Pneumovirus reverse genetics” was filed on 26 February 2019. However, this application was discontinued and allowed to lapse in August 2020.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2026558118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The RSV genome sequence data reported in this article have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. MW582527–MW582529). All data are available in the main text and SI Appendix. Additional RSV-A2 sequence data is available via ref. 69.

References

- 1.Thorburn K., Harigopal S., Reddy V., Taylor N., van Saene H. K., High incidence of pulmonary bacterial co-infection in children with severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis. Thorax 61, 611–615 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meskill S. D., O’Bryant S. C., Respiratory virus co-infection in acute respiratory infections in children. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 22, 3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien K. L.et al.; Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) Study Group , Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: The PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet 394, 757–779 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden F. G., Whitley R. J., Respiratory syncytial virus antivirals: Problems and progress. J. Infect. Dis. 222, 1417–1421 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.PATH , RSV vaccine and mAb snapshot: PATH vaccine resource library (2020). https://www.path.org/resources/rsv-vaccine-and-mab-snapshot/. Accessed 9 November 2020.

- 6.Walsh E. E., Hruska J., Monoclonal antibodies to respiratory syncytial virus proteins: Identification of the fusion protein. J. Virol. 47, 171–177 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hause A. M., et al., Sequence variability of the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion gene among contemporary and historical genotypes of RSV/A and RSV/B. PLoS One 12, e0175792 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Battles M. B., McLellan J. S., Respiratory syncytial virus entry and how to block it. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 233–245 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olmsted R. A., et al., Expression of the F glycoprotein of respiratory syncytial virus by a recombinant vaccinia virus: Comparison of the individual contributions of the F and G glycoproteins to host immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 7462–7466 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson S., et al., Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody (MEDI-493) with potent in vitro and in vivo activity against respiratory syncytial virus. J. Infect. Dis. 176, 1215–1224 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLellan J. S., Yang Y., Graham B. S., Kwong P. D., Structure of respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein in the postfusion conformation reveals preservation of neutralizing epitopes. J. Virol. 85, 7788–7796 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto K., Hosoya M., Neutralizing epitopes of RSV and palivizumab resistance in Japan. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 63, 127–134 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson L. J., et al., Antigenic characterization of respiratory syncytial virus strains with monoclonal antibodies. J. Infect. Dis. 151, 626–633 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mufson M. A., Orvell C., Rafnar B., Norrby E., Two distinct subtypes of human respiratory syncytial virus. J. Gen. Virol. 66, 2111–2124 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun K. W., Choi E. H., Lee H. J., Molecular epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus for 28 consecutive seasons (1990–2018) and genetic variability of the duplication region in the G gene of genotypes ON1 and BA in South Korea. Arch. Virol. 165, 1069–1077 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandini S., Biagi C., Lanari M., Respiratory syncytial virus: The influence of serotype and genotype variability on clinical course of infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1717 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devincenzo J. P., Natural infection of infants with respiratory syncytial virus subgroups A and B: A study of frequency, disease severity, and viral load. Pediatr. Res. 56, 914–917 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fodha I., et al., Respiratory syncytial virus infections in hospitalized infants: Association between viral load, virus subgroup, and disease severity. J. Med. Virol. 79, 1951–1958 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eshaghi A., et al., Genetic variability of human respiratory syncytial virus A strains circulating in Ontario: A novel genotype with a 72 nucleotide G gene duplication. PLoS One 7, e32807 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trento A., et al., Major changes in the G protein of human respiratory syncytial virus isolates introduced by a duplication of 60 nucleotides. J. Gen. Virol. 84, 3115–3120 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hotard A. L., Laikhter E., Brooks K., Hartert T. V., Moore M. L., Functional analysis of the 60-nucleotide duplication in the respiratory syncytial virus Buenos Aires strain attachment glycoprotein. J. Virol. 89, 8258–8266 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chirkova T., et al., CX3CR1 is an important surface molecule for respiratory syncytial virus infection in human airway epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 2543–2556 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeong K. I., et al., CX3CR1 is expressed in differentiated human ciliated airway cells and co-localizes with respiratory syncytial virus on cilia in a G protein-dependent manner. PLoS One 10, e0130517 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson S. M., et al., Respiratory syncytial virus uses CX3CR1 as a receptor on primary human airway epithelial cultures. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005318 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karron R. A., et al., Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) SH and G proteins are not essential for viral replication in vitro: Clinical evaluation and molecular characterization of a cold-passaged, attenuated RSV subgroup B mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 13961–13966 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeFord D. M., et al., Evaluation of the role of respiratory syncytial virus surface glycoproteins F and G on viral stability and replication: Implications for future vaccine design. J. Gen. Virol. 100, 1112–1122 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim Y. I., et al., Relating plaque morphology to respiratory syncytial virus subgroup, viral load, and disease severity in children. Pediatr. Res. 78, 380–388 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Gucht W., et al., Isolation and characterization of clinical RSV isolates in Belgium during the winters of 2016–2018. Viruses 11, 1031 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullender W. M., Respiratory syncytial virus genetic and antigenic diversity. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13, 1–15 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandya M. C., Callahan S. M., Savchenko K. G., Stobart C. C., A contemporary view of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) biology and strain-specific differences. Pathogens 8, 67 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins P. L., et al., Rational design of live-attenuated recombinant vaccine virus for human respiratory syncytial virus by reverse genetics. Adv. Virus Res. 54, 423–451 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chanock R., Roizman B., Myers R., Recovery from infants with respiratory illness of a virus related to chimpanzee coryza agent (CCA). I. Isolation, properties and characterization. Am. J. Hyg. 66, 281–290 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis F. A., Rae M. L., Lehmann N. I., Ferris A. A., A syncytial virus associated with epidemic disease of the lower respiratory tract in infants and young children. Med. J. Aust. 2, 932–933 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins P. L., et al., Production of infectious human respiratory syncytial virus from cloned cDNA confirms an essential role for the transcription elongation factor from the 5′ proximal open reading frame of the M2 mRNA in gene expression and provides a capability for vaccine development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 11563–11567 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rameix-Welti M. A., et al., Visualizing the replication of respiratory syncytial virus in cells and in living mice. Nat. Commun. 5, 5104 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu B., et al., Development of a reverse genetics system for respiratory syncytial virus Long strain and an immunogenicity study of the recombinant virus. Virol. J. 11, 142 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu M., et al., Construction and characterization of a recombinant human respiratory syncytial virus encoding enhanced green fluorescence protein for antiviral drug screening assay. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 8431243 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almazán F., et al., Engineering the largest RNA virus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5516–5521 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yun S. I., Kim S. Y., Rice C. M., Lee Y. M., Development and application of a reverse genetics system for Japanese encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 77, 6450–6465 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hotard A. L., et al., A stabilized respiratory syncytial virus reverse genetics system amenable to recombination-mediated mutagenesis. Virology 434, 129–136 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lemon K., et al., Recombinant subgroup B human respiratory syncytial virus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein efficiently replicates in primary human cells and is virulent in cotton rats. J. Virol. 89, 2849–2856 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rennick L. J., et al., Recombinant subtype A and B human respiratory syncytial virus clinical isolates co-infect the respiratory tract of cotton rats. J. Gen. Virol. 101, 1056–1068 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arbiza J., et al., Characterization of two antigenic sites recognized by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies directed against the fusion glycoprotein of human respiratory syncytial virus. J. Gen. Virol. 73, 2225–2234 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heminway B. R., et al., Analysis of respiratory syncytial virus F, G, and SH proteins in cell fusion. Virology 200, 801–805 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pastey M. K., Samal S. K., Analysis of bovine respiratory syncytial virus envelope glycoproteins in cell fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 78, 1885–1889 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gower T. L., et al., RhoA signaling is required for respiratory syncytial virus-induced syncytium formation and filamentous virion morphology. J. Virol. 79, 5326–5336 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meshram C. D., Baviskar P. S., Ognibene C. M., Oomens A. G. P., The respiratory syncytial virus phosphoprotein, matrix protein, and fusion protein carboxy-terminal domain drive efficient filamentous virus-like particle formation. J. Virol. 90, 10612–10628 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blount R. E. Jr., Morris J. A., Savage R. E., Recovery of cytopathogenic agent from chimpanzees with coryza. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 92, 544–549 (1956). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hambling M. H., Survival of the respiratory syncytial virus during storage under various conditions. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 45, 647–655 (1964). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altamirano-Lagos M. J., et al., Current animal models for understanding the pathology caused by the respiratory syncytial virus. Front. Microbiol. 10, 873 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ternette N., Stefanou D., Kuate S., Uberla K., Grunwald T., Expression of RNA virus proteins by RNA polymerase II dependent expression plasmids is hindered at multiple steps. Virol. J. 4, 51 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang K., et al., Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus F protein expression is hindered by inefficient nuclear export and mRNA processing. Virus Genes 40, 212–221 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnell M. J., Mebatsion T., Conzelmann K. K., Infectious rabies viruses from cloned cDNA. EMBO J. 13, 4195–4203 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clarke D. K., Sidhu M. S., Johnson J. E., Udem S. A., Rescue of mumps virus from cDNA. J. Virol. 74, 4831–4838 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takeda M., et al., Recovery of pathogenic measles virus from cloned cDNA. J. Virol. 74, 6643–6647 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Villenave R., et al., In vitro modeling of respiratory syncytial virus infection of pediatric bronchial epithelium, the primary target of infection in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5040–5045 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coates H. V., Alling D. W., Chanock R. M., An antigenic analysis of respiratory syncytial virus isolates by a plaque reduction neutralization test. Am. J. Epidemiol. 83, 299–313 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hierholzer J. C., et al., Subgrouping of respiratory syncytial virus strains from Australia and Papua New Guinea by biological and antigenic characteristics. Arch. Virol. 136, 133–147 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rostad C. A., et al., A recombinant respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate attenuated by a low-fusion F protein is immunogenic and protective against challenge in cotton rats. J. Virol. 90, 7508–7518 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Q., et al., Analysis of respiratory syncytial virus preclinical and clinical variants resistant to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies palivizumab and/or motavizumab. J. Infect. Dis. 203, 674–682 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jin H., et al., Recombinant human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) from cDNA and construction of subgroup A and B chimeric RSV. Virology 251, 206–214 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klimstra W. B., et al., SARS-CoV-2 growth, furin-cleavage-site adaptation and neutralization using serum from acutely infected hospitalized COVID-19 patients. J. Gen. Virol. 101, 1156–1169 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palermo L. M., et al., Features of circulating parainfluenza virus required for growth in human airway. mBio 7, e00235 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szpara M. L., Parsons L., Enquist L. W., Sequence variability in clinical and laboratory isolates of herpes simplex virus 1 reveals new mutations. J. Virol. 84, 5303–5313 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Connors M., Crowe J. E. Jr., Firestone C. Y., Murphy B. R., Collins P. L., A cold-passaged, attenuated strain of human respiratory syncytial virus contains mutations in the F and L genes. Virology 208, 478–484 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whitehead S. S., Juhasz K., Firestone C. Y., Collins P. L., Murphy B. R., Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bearing a set of mutations from cold-passaged RSV is attenuated in chimpanzees. J. Virol. 72, 4467–4471 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liang B., et al., Enhanced neutralizing antibody response induced by respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein expressed by a vaccine candidate. J. Virol. 89, 9499–9510 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lawlor H. A., Schickli J. H., Tang R. S., A single amino acid in the F2 subunit of respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein alters growth and fusogenicity. J. Gen. Virol. 94, 2627–2635 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.American Type Culture Collection , ATCC genome portal (2019). genomes.atcc.org/. Accessed 27 October 2020.

- 70.Stokes K. L., et al., Differential pathogenesis of respiratory syncytial virus clinical isolates in BALB/c mice. J. Virol. 85, 5782–5793 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rijsbergen L. C., et al., In vivo comparison of a laboratory-adapted and clinical-isolate-based recombinant human respiratory syncytial virus. J. Gen. Virol. 101, 1037–1046 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anderson L. J., Peret T. C., Piedra P. A., RSV strains and disease severity. J. Infect. Dis. 219, 514–516 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thi Nhu Thao T., et al., Rapid reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 using a synthetic genomics platform. Nature 582, 561–565 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Caidi H., Harcourt J. L., Haynes L. M., RSV growth and quantification by microtitration and qRT-PCR assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 1442, 13–32 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kärber G., Beitrag zur kollektiven Behandlung pharmakologischer Reihenversuche. Naung-Schmiedebegs Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 162, 480–483 (1931). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jo W. K., et al., Evolutionary evidence for multi-host transmission of cetacean morbillivirus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 7, 201 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Katoh K., Rozewicki J., Yamada K. D., MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 1160–1166 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nguyen L. T., Schmidt H. A., von Haeseler A., Minh B. Q., IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B. Q., Wong T. K. F., von Haeseler A., Jermiin L. S., ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Adams O., et al., Palivizumab-resistant human respiratory syncytial virus infection in infancy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51, 185–188 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RSV genome sequence data reported in this article have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. MW582527–MW582529). All data are available in the main text and SI Appendix. Additional RSV-A2 sequence data is available via ref. 69.