Abstract

Background: Many trans and non-binary people wish to be parents. However, few countries record figures for trans and non-binary people becoming pregnant/impregnating their partners. Pregnant non-binary people and trans men may be growing populations, with heightened vulnerabilities to traumatic birth and perinatal mental health difficulties (i.e. pregnancy-one year postpartum).

Aim: To conduct a scoping review on traumatic birth and perinatal mental health in trans and non-binary people to identify research evidence, summarize findings, and identify gaps.

Methods: Electronic databases were searched to identify published English-language evidence. Eligibility was not restricted by type of study, country, or date.

Findings: All studies were from the Global North and most participants were white. The literature focuses on structural and psychological barriers faced by non-binary people and trans men and on the lack of reliable medical information available. There is a lack of empirical research and, to date, no research into trans and non-binary parents’ experiences has focused on traumatic birth or perinatal mental health. However, common themes of dysphoria, visibility, isolation, and the importance of individualized respectful care indicate potential vulnerability factors. Trans women’s and non-binary people’s experiences are particularly under-researched.

Discussion: The themes of dysphoria, visibility, and isolation present a series of challenges to pregnant non-binary people and trans men. These coalesce with external events and internal choices, creating the potential to make the individual feel not man enough, not trans enough, not pregnant enough, and not safe enough during pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum. Further research involving trans people is needed to inform future services.

Keywords: Birth, dysphoria, mental health, non-binary, perinatal, pregnancy, trauma, transgender

Introduction

Currently, Australia is the only country that routinely collects data on gender in perinatal services (Pearce, 2019). This means that in other countries trans and non-binary parents are not identifiable within maternity data and we cannot examine differential experiences of services and inequalities. For example, analyzing by ethnicity reveals significant disparities in mortality (Knight et al., 2019) and mental health morbidity (Watson et al., 2019) for Black and Asian birthing parents in the UK.

Perinatal mental health (PMH) difficulties impact one in five birthing cisgender (cis) women (NICE, 2014). In addition, 5–15% of cis fathers experience perinatal depression and anxiety (Cameron et al., 2016; Leach et al., 2016). Relevant too are severe fear of childbirth (tokophobia) and traumatic birth. Up to 30% of birthing parents in the UK experience childbirth as a traumatic event, with many subsequently experiencing anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Slade, 2006). Figures are comparable across countries with similar healthcare systems, 24% in Australia (Toohill et al., 2014) and 34% in the United States (Soet et al., 2003). If left untreated, traumatic birth poses long-term effects, including enduring mental health difficulties, depression in partners, compromised parent-infant and inter-parent relationships, and challenging future reproductive decisions (Greenfield et al., 2016). Partners may themselves experience birth as traumatic (Leach et al., 2016).

Prevalence of PMH difficulties and traumatic birth in trans and non-binary parents is unknown. Any parent can experience perinatal mental illness or traumatic birth. However, pre-disposing factors include history of mental illness, trauma or abuse, lack of social support, and poor care (Andersen et al., 2012; Lancaster et al., 2010; Leach et al., 2017). Learning from the general transgender population (outside of the perinatal period) could indicate increased vulnerability to traumatic birth and PMH difficulties. For example, trans people experience high rates of mental health difficulties and suicidality, which have been linked to stigma and traumatic encounters with transphobia (Bockting et al., 2013; McNeil et al., 2017). LGBT + people also face higher risk of lack of social support and experiencing discrimination within their families (Ross et al., 2005).

It is increasingly recognized that trans and non-binary people are becoming parents; yet invisibility continues in policy, with language of maternal mental health and paternal mental health reflecting cis-heteronormativity (Riggs et al., 2016). To address trans and non-binary parents’ needs and experiences and to deepen understanding of PMH and traumatic birth, it is timely to review the research evidence in this emerging field.

Methods and materials

This review aimed to:

identify and summarize the available research evidence about PMH difficulties and traumatic birth amongst trans and non-binary parents,

identify any evidence gaps and,

make recommendations about future research priorities.

Scoping reviews are ideally suited to these aims, mapping an emerging and variable literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). The methods followed the stages described elsewhere (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010), and with the approach to thematic analysis specified as following (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Relevant scoping review reporting guidelines (known as PRISMA-ScR) were followed (Tricco et al., 2018) to increase methodological transparency (for example, concerning searching and eligibility criteria).

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The question was intentionally broad:

What does research evidence tell us about perinatal mental health difficulties and traumatic birth amongst trans and non-binary parents?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

The following electronic databases were searched in 2019 and updated in 2020: Cochrane, PsycINFO, PsycArticles, CINAHL, and MEDLINE. The search terms were:

Line 1: transgender OR nonbinary OR non-binary OR gender fluid OR gender-fluid OR transmasculine OR gender-diverse OR gender-variant OR transexual OR transsexual AND

Line 2: pregnan* OR prenatal OR antenatal OR antepartum OR postnatal OR postpartum OR perinatal OR *birth OR maternityAND

Line 3: trauma* OR mental health OR depress* OR anxi* OR distress OR mental illness OR psychopathology OR experience*

The electronic search was complemented by backward and forward citation chaining.

Stage 3: study selection1

The lead reviewer screened all titles and abstracts and obtained any potential includable records in full. Papers were included if they discussed trans and non-binary people’s experiences of giving birth or being present at their child’s birth or mental health or psychological wellbeing in the perinatal period (including experiences, prevalence, and vulnerability factors). Literature was excluded if it focused on fertility, assisted conception, or future reproductive plans, without discussion of birth experiences or PMH.

There was no restriction by study design; we included review papers, briefing notes, and empirical studies. Single case studies published in a peer-reviewed academic or practitioner journal were eligible; personal birth stories, blogs, and media articles were excluded. No date restriction was applied. Eligibility was restricted to English-language publications due to the reviewers’ language limitations.

Stage 4: charting the data

Both researchers reviewed the included papers to identify and chart emerging themes and ideas. Data extraction included study aims, participant characteristics, data collection and analysis, relevant findings, and recommendations. Following Levac et al. (2010), charting was iterative and was further refined following Stage 6.

Stage 5a: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

A descriptive summary of the papers was generated to provide a coherent structure to the literature before providing a thematic analysis of the included studies’ findings. Consistent with scoping review methodology, it was not the authors’ aim to assess study quality.

Stage 5b: thematic analysis

Thematic analysis followed the process described by Braun and Clarke (2006). Charting and summarizing provided the necessary familiarization for both researchers. Initial codes were generated inductively and then grouped together as themes. Each theme was named and described, drawing on the extracted and charted data.

Stage 6: informal consultation exercise

Arksey and O’Malley (2005) suggest an optional consultation stage with practitioners and consumers to validate the review’s direction and identify further literature. While we did not conduct a formal consultation exercise, sharing the review’s preliminary findings at the Trans Pregnancy Conference in January 2020 offered the opportunity to invite feedback on early findings and refine our thinking. Specifically, discussions with delegates (including parents and academics) raised the issue that gender dysphoria could be experienced as either physical or social, with potential implications for the strategies used by pregnant non-binary people and trans men. This led us to revisit charting and naming of the themes that became “Dysphoria” and “Visibility and recognition.”

Findings

Overview of included literature

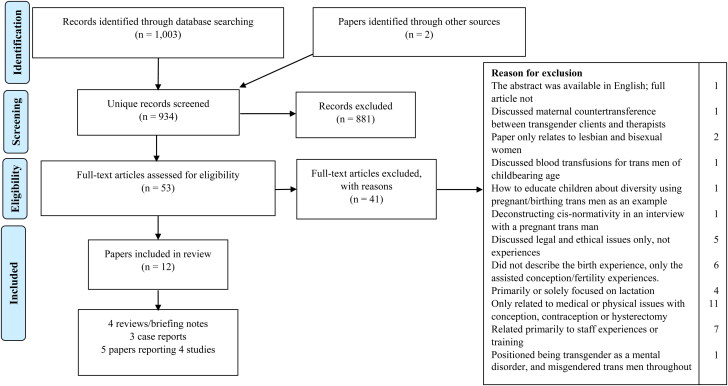

The database searches and complimentary strategies identified 934 unique records. Most (881/934) were identified as ineligible based on title/abstract; for example, papers examining antecedents of offspring being transgender or gender-inclusive contraception and pregnancy-prevention.

Of the 53 full-text articles assessed, 12 met eligibility requirements. Reasons for exclusion are outlined in Figure 1; a full list of records is available from the first author. The 12 eligible articles included two literature reviews, a commentary, a briefing note based on existing literature (Table 1), three case reports (Table 2), and five papers reporting four primary studies that used interview and/or survey methods (Table 3).

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR (Tricco et al., 2018) flow diagram.

Table 1.

Literature reviews, commentary and briefing notes (n = 4).

| Paper ID, first author, year, country, aim | Methods | Relevant findings and/or recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Brandt et al. 2019, USA Aim: discuss obstetrical issues for transgender men aged ≥35 |

|

|

| 2. de Castro-Peraza et al. 2019, Spain Aim: describe aspects of transgender biological-gestational parenthood, informed by a specific legal case |

|

|

| 3. Wisner 2018, USA Aim: brief for nurses |

|

|

| 4. Obedin-Maliver & Makadon 2016, USA Aim: provide guidance for clinicians |

|

|

Table 2.

Case reports (n = 3).

| Paper ID, first author, year, country, Aim | Sample characteristics | Data collection and analysis | Relevant findings and/or recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5. Hahn et al. 2019, USA Aim: not stated |

1 trans man (20) accessing perinatal care |

Single case report Reflective account by service providers |

|

| 6. Stroumsa et al. 2019, USA Aim: not stated |

1 trans man (32) accessing emergency department |

Single case report Chronological account (source unclear) |

|

| 7. Wolfe-Roubatis & Spatz 2015, USA Aim: illustrate transgender men’s concerns and experiences regarding lactation and infant feeding |

2 participants (45 and late 20’s) recruited via social media and word of mouth | Case studies, based on individual interviews with two parents and a nurse practitioner specializing in the care of gender diverse people |

|

Table 3.

Primary studies using interview/survey methods (n = 4, reported in 5 papers)

| Paper ID, first author, year, country, aim, design | Recruitment | Sample characteristics | Data collection and analysis | Relevant findings and/or recommendations relating to birth trauma and PMH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8. Charter et al. 2018, Australia Aim: explore how Australian trans men construct and experience (i) their desire for parenthood and (ii) gestational pregnancy Design: mixed methods (survey and interview) |

Information sheet via transgender support groups/ community organizations, social media Survey participants indicated interest in interview |

25 trans men who had been pregnant Mean age 25 (range 24-46). Gestational children aged 3-12 years. Majority 1 pregnancy (24/25). Majority parented other children. Majority partnered (13/21). Range of sexual orientations. Majority Australian. Ethnicity not reported. Majority University degree. |

Online survey (closed/open-ended questions) (n = 25), semi-structured telephone interviews (n = 16) Thematic analysis for qualitative data |

|

| 9. Ellis et al. 2015, USA Aim: explore conception, pregnancy, and birth experiences of male and gender-variant gestational parents who had socially or medically transitioned prior to pregnancy Design: qualitative |

Recruited by health/social care providers; some participants recruited others within community networks |

8 male-identified or gender-variant gestational parents Mean age 33 (29-41). Gestational children aged <5 years. All 1-2 children. Majority partnered. Range of gender identities and sexual orientations. All participants were white. Range of educational experiences. Mixed urban/rural settings. Most had given birth in hospital, 2 at home. Eligibility: pregnant in past 5 years resulting in live birth; not currently pregnant; self-identify as male or gender variant; disclosure of gender identity to at least some health care providers; English fluency. |

Video-call interviews supplemented by online demographic survey Grounded Theory |

|

| 10. Hoffkling et al. 2017, USA and Western Europe Aim: understand the needs of transgender/transmasculine men who had given birth Design: qualitative Note: papers 10 and 11 taken from a larger mixed methods study |

Recruited from an online survey (paper 11) Interviews were conducted until theoretical saturation reached Note: Recruitment method meant non-binary trans people were specifically excluded |

10 transgender men who had given birth while identifying as male 1-4 pregnancies; 1-3 live births. Range of relationship status (numbers not reported). 8 were from USA, 2 from Western Europe. Other demographics were not reported. Eligibility: see paper 11 |

Individual semi-structured interviews by video (n = 8) or phone (n = 2) Grounded Theory |

|

| 11. Light et al. 2014, USA (majority) Aim: conduct a cross-sectional study of transgender men who had been pregnant after transitioning from female-to-male to help guide practice and further investigation Design: survey Note: papers 10 and 11 taken from a larger mixed methods study |

Recruitment via LGBT + community organizations and targeted social media, then utilized snowball methodology |

41 self-described transgender men 15 (37%) had ≥2 pregnancies. Mean age 28. Majority white. Majority completed some college. “Limited socioeconomic and racial diversity.” Majority lived in USA (35/41; 85%). Eligibility: pregnant within past 10 years resulting in live birth; self-identify as male before pregnancy; aged 18+; English fluency |

Online survey (closed/open-ended questions) Quantitative data analyzed statistically. Grounded Theory used for qualitative survey data. |

|

| 12. Malmquist et al. 2019, Sweden Aim: explore and describe thoughts about/experiences of pregnancy and childbirth in lesbian and bisexual women and transgender people (LBT) with an expressed Fear of Childbirth (FOC) Design: qualitative |

Four participants were interviewed in a previous study, spontaneously mentioning fear of childbirth. 11 additional participants were recruited through social media groups for LGBT families. | 17 self-identified LBTs Majority identified as lesbian or bisexual women, and “a few” identified as trans men or non-binary (numbers not reported but includes a trans male couple). Aged 25-42. 0-4 children. Diverse range of family formations. Majority were partnered. Majority University degree and employed. |

Individual (n = 9) and couple (n = 4) semi-structured face-to-face interviews, supplemented in second set of participants by the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/ Experience questionnaire Thematic analysis |

|

The earliest research evidence included was published in 2014 (Study ID 11), with five published since 2019. The literature comes from North America, Western Europe, and Australia; all were from the Global North. The literature reviews, commentary, and briefing report spanned wider aspects of trans parenthood and were targeted at learning for health professionals; all included some mention of psychological aspects or mental health, with two explicitly referring to postpartum depression (PPD), and one to the potential for “vaginal birth [to be] traumatic and disturbing.” Issues concerning language are returned to in the discussion. The three case reports varied concerning participant involvement, with some based on reflective learning by practitioners. Their foci included gender-affirming perinatal care, traumatic loss in an emergency department, and lactation and infant feeding.

Recruitment strategies predominantly utilized social media and community support organizations for LBGT + people. Selection of participants varied, with some studies only including trans men, whilst others included non-binary people too. Definitions of these terms were not always given and, where they were, were not consistent between studies. Sample size ranged from 1 to 2 in the three case studies, 8 to 17 in the four interview studies, and 25 to 41 in surveys. Participants were of varied ages and sexual orientations. Ethnicity data was not given in consistent categories; where it was given, participants were predominantly white. Where relationship status was reported, some participants were currently single and others were partnered. The literature focuses on structural and psychological barriers faced by participants and on the lack of reliable medical information available. Only paper 12 focused on PMH or traumatic birth and this was only the paper that concerned a mixed population (lesbian and bisexual women and transgender people).

Themes

Although no research has focused on traumatic birth or PMH among non-binary people and trans men, six themes relevant to psychological wellbeing were identified.

Dysphoria

The literature discusses the varied impact of pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum on gender dysphoria, with specific points including: discontinuing testosterone therapy, changes to the chest, being socially read as pregnant, giving birth, and lactation. In this review, and guided by discussion in the consultation exercise, we broadened our approach to dysphoria to explicitly address both embodied experiences that may be considered “physical dysphoria” and extrinsic “social dysphoria,” relating to anticipated or experienced reactions or treatment by others. Within the literature, the distinction between the two was either not made explicit or dysphoria was used only to refer to intrinsic physical dysphoria, with extrinsic social dysphoria described differently. For example, paper 9 describes participants as experiencing “conflict… between their internal sense of self and dominant social norms that define a pregnant person as woman” (9). However, elsewhere, MacDonald et al. (2016) identified that trans men’s chest dysphoria during lactation can be either social or physical.

Other included papers discussed that some participants experienced disconnection or alienation from the pregnant body (4), terming this “disembodiment” (9). It appears that this disconnection could follow the changes to the body caused by pregnancy or could be preemptive, anticipating changes (4, 9). Assisted conception and perinatal loss appeared to exacerbate these feelings, as individuals experienced a loss of control over their bodies, feelings of frustration, and shame that their body was not working as they felt it should (9).

No studies report that individuals had neutral feelings about their pregnant bodies. Some pregnant participants found the bodily changes of pregnancy distressing (11), whilst others enjoyed them and “felt more attractive” during pregnancy, although this could itself provoke internal conflict at feeling “less of a man” (8). A similar split seems to occur in feelings about birth. Some participants found even the idea of vaginal birth traumatic, with particular emphasis given to concerns about having their genitals exposed for a prolonged period (1, 9). In the same studies, other participants found a vaginal birth to be meaningful for them and experienced “a lack of inhibition during labor and birth that transcended their usual concerns about gender identity and revealing their bodies to others” (9).

Visibility and recognition

Visibility emerges as a complex issue for pregnant non-binary people and trans men to navigate. This links to challenges concerning identity when met with lack of social and legal recognition as a parent and negotiating dysphoria (9). Being visible may require being permanently “out” (10) and for some, this can be uncomfortable (2), or even potentially dangerous (8; 10). Although none of the studies linked this to traumatic birth, entering labor or birth feeling unsafe or threatened is a factor which makes traumatic birth more likely (Slade, 2006). In one study, authors report that feeling physically unsafe as visibly-pregnant men led some to a decision to simply cope with social misperception either as fat cis men or pregnant cis women (2).

Neither of these options appears to be without further consequence. Being socially misperceived as a fat cis man was identified as in paper 8 as leading to emotional isolation and being unable to enjoy the pregnancy fully. Being socially misperceived as a pregnant cis woman (2) has further implications for potentially increasing dysphoria (10). Individuals’ strategies to navigate visibility may be interpreted as increasing both physical safety and safety from social dysphoria. Participants in several studies reported high need for gender affirmation during the perinatal period from healthcare professionals, with recognition centered around pronoun and language use (4; 5; 7; 8; 10).

Isolation and exclusion

Physical, social, and emotional isolation and exclusion were identified as common features of non-binary people and trans men’s pregnancies and some individuals’ early postpartum experiences (2; 4; 8; 9; 10; 11). This isolation and exclusion was intimately linked with the experiences of either physical or social dysphoria and visibility. Some men chose physical isolation as a strategy for limiting their discomfort with being a visibly-pregnant man (8). Physically isolating was described as avoiding the potential risks to physical and emotional safety without being socially misperceived as a pregnant cis woman (2) or needing to conceal the pregnancy.

Although described as an adaptive coping mechanism and beneficial to some pregnant trans people’s psychological wellbeing (8), physical isolation may be accompanied by loneliness (9). Isolation was noted repeatedly (2; 4; 8; 9; 10; 11), with participants voicing feeling that they are the only person in this situation. Feelings of social exclusion appear to be exacerbated by healthcare services, where pregnant men may be uncomfortably visible in physical and notional spaces that are usually exclusive to cisgender women (2). Some participants felt further isolated by the complete lack of healthcare images and language reflecting pregnant trans men (11). Whilst there is no research into the effects of loneliness and isolation during pregnancy on non-binary people’s and trans men’s PMH, these experiences are known to be linked to PPD in cisgender women (8).

Anticipated and experienced poor care

Poor care featured in paper 12 and in other studies where it was identified as a factor impacting the psychological wellbeing of birthing non-binary people and trans men (4; 8; 11). Non-binary people’s and trans men’s anticipation of poor perinatal care experiences appear shaped by community and individual previous experiences, reflecting wider transphobia and inexperience amongst healthcare providers (9; 10). Examples included preventable baby loss (6), fertility treatment being inaccessible (8), and a lack of appropriate services for postnatal support (7; 11). Culturally competent care for birthing non-binary people and trans men includes both medically correct care and the use of appropriate individualized and respectful language (4; 5). Some authors (4;5) emphasize that understanding the importance of individualized and respectful perinatal care for this population can have a positive impact on PMH.

Choice and control

The literature identified that trans men participants made diverse birth choices concerning mode and place of birth; these may include more homebirths (1) and elective cesarean births (11). Sometimes these choices are not initially positive, instead driven by fear of poor care and choosing the perceived least bad option (10) in order to retain control during birth. Which choice offers an individual a feeling of greater control may depend on the interplay of one’s personal history with social and physical dysphoria. The importance of having birth and language choices respected is attested to across all the papers with only one exception (6).

Increased vulnerability to PMH difficulties and traumatic birth

Prevalence rates of PMH difficulties and traumatic births among trans men are unknown (1). However, several articles proposed that non-binary people and trans men may face increased vulnerability (1; 3; 8; 10; 11). The loss of control experienced during pregnancy and birth may impact PMH (9) and there may be additional vulnerability to severe fear of childbirth and traumatic birth due to feared or experienced prejudicial treatment and hypervigilance because of experiences of transphobia and misgendering (12). Although most of the studies discussed dysphoria, only a minority framed this as a potential risk or contributory factor to depression (11). Isolation was also linked to depression (11) and poorer PMH (4).

Despite potential increased vulnerability, in the single study that commented on awareness of PMH, participants did not recall health professionals discussing PPD (10). Furthermore, it appeared that some participants may struggle to identify differences between, for example, depression, mood swings, and dysphoria (10).

Discussion

This review shows that little is known about the PMH and traumatic birth experiences or prevalence in non-binary people and trans men. However, several authors propose vulnerability may be heightened. Reported difficulties relevant to psychological wellbeing share some similarities with those reported by cis women; for example, concerning loneliness, poor care, and a loss of choice and control.

Research with cis women and cis men finds they share common psychosocial risk factors for perinatal anxiety and depression. It seems likely that these risk factors will also be relevant for trans and gender-diverse parents but that some may be particularly salient; for example, mental health history, history of trauma (including by healthcare providers), and poor social support. Psychosocial risk factors for traumatic birth include previous traumatic experiences, preexisting mental health difficulties, poor care (or the perception of poor care) during labor, and loss of choice and control during birth (Czarnocka & Slade, 2000; Greenfield et al., 2016; O’Donovan et al., 2014), all of which may be more likely in pregnant non-binary people and trans men when compared to pregnant cis women.

For example, transgender populations are disproportionately affected by violence (Lombardi et al., 2002) and other forms of trauma (Mizock & Lewis, 2008), increasing the likelihood of entering pregnancy with a history of previous trauma. Non-binary and binary transgender people in the general population face mental health inequalities, including higher rates of diagnosed mental health conditions (Jones et al., 2019). As the included studies have shown, poor care during labor and birth is experienced by some non-binary people and trans men, and previous experiences of poor care from healthcare providers may result in hypervigilance, thus increasing the perception of poor care. Loss of choice and control is also indicated here, linked to misgendering, fear of poor care, and not feeling the full range of choices are truly available for pregnant non-binary people and trans men.

Pregnant non-binary people and trans men may also face distinct vulnerability to traumatic birth or PMH difficulties that cis women do not. These factors include dysphoria, isolation and exclusion, and culturally incompetent care. Additionally, we propose that gender dysphoria warrants specific consideration in addressing the PMH of non-binary people and trans men and with attention both to physical embodied dysphoria and to extrinsic social aspects. Taken together, the themes of visibility, isolation, and dysphoria can be conceived of as presenting a series of challenges to some pregnant trans men, with external events and internal choices having the potential to make the individual feel not man enough (8; 9; 10; 11), not trans enough (9), not pregnant enough (8; 9; 10), and not safe enough during pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum (8; 10; 12). This must also be balanced with the recognition that these experiences will not be shared by all trans and non-binary parents and that some participants report improvements in gender dysphoria (10), feeling “new connection” to their body (11), and finding vaginal birth “a meaningful experience” (9).

Identified gaps and research priorities

Our review confirmed that research about trans and non-binary birthing parents is a newly emerging field, with the earliest literature relating to traumatic birth and PMH published in 2014. To date, research focused on PMH or traumatic birth has not examined the experiences of trans parents.

Within a newly emerging research evidence base, gaps are inevitable. The primary focus of this literature is on the structural and psychological barriers faced by trans men and non-binary people pursuing parenthood, and the limited availability of reliable medical information informing those pursuits. This is situated against a background where accessing appropriate healthcare is difficult for many trans and non-binary people, with healthcare professionals rarely having medically appropriate knowledge (Grant et al., 2010). Indeed, up to a third of trans patients in the USA and UK report that healthcare professionals have refused to treat them because they are transgender (Roller et al., 2015).

We identified that pregnant non-binary people were often either directly excluded from research or were assumed to have identical needs to those of pregnant trans men. This position as a minority group within a minority population means that it is difficult to draw conclusions about the perinatal needs of non-binary people. There is also no research into trans women’s experiences of pregnancy and birth, for example as the lesbian partner of a pregnant cisgender woman, and no research into lesbian birth experiences has identified trans women’s experiences separately from cisgender women.

To date, no research has included the experience of non-gestational parents, either as the partner of a pregnant non-binary person or trans man, or as a transgender parent themselves. In the literature reviewed, only one paper (12) references trans men as partners of the birthing parent, hypothesizing that partners’ fear of childbirth could be different where both partners have childbearing capacity. However, the paper does not report on this as an experience, only as a theoretical possibility. Further, intersectionality has not yet featured in this literature, foregrounding gender and not yet having considered this alongside other characteristics including socioeconomic factors, race and ethnicity, or age. This is particularly troubling in the context of established inequalities concerning race and ethnicity; for example, concerning parents’ mortality (Knight et al., 2019) and PMH morbidity (Watson et al., 2019) in the perinatal period.

Also troubling are instances where authors use language that is inaccurate, inappropriate, or potentially excluding; for example “breastfeeding” (paper 9), “vaginal birth” (1;9), “vaginal delivery” (2;5;11), “passing as a woman” (9;10), and “impersonate cisgender women” (2). This is particularly pertinent given that the theme of anticipated and experienced poor care illustrates the need for culturally competent care that uses individualized and respectful language. Just as in practice, there needs to be progress made with language, this is also true for research communities.

In many high-income settings, PMH is now routinely assessed in birthing parents. PMH research identifies potential gendered differences in the symptoms expressed by cis women and cis men, leading to calls for male-specific measures (Matthey & Della Vedova, 2020) or “gender-inclusive” approaches to mental health (Martin et al., 2013). One paper (1) noted that routine assessment of all birthing parents focuses on depression and is not designed to assess dysphoria, and the authors of another paper (10) noted the need for health professionals’ vigilance in monitoring mental health, reporting that parents may struggle to differentiate between, for example, depression, mood swings, and dysphoria. However, we found no studies examining mental health assessment in trans parents and recommend that this be addressed by research conducted in applied settings.

Strengths and limitations

A limitation of scoping reviews is that they are not considered sufficiently rigorous to form the basis of policy and practice recommendations (Grant & Booth, 2009). With a literature this small and diverse, it is inevitable that there are issues relating to the quality and robustness of some literature. We do not propose directly influencing current practice but rather sought to demonstrate the current research evidence on PMH and traumatic birth in trans men and non-binary people and identify research priorities. We only included published articles which had been subjected to peer-review and intentionally excluded first-person accounts in books, blogs, and forums. Such restrictions are commonly used to promote rigor and clearly identify research evidence gaps but we note that this limits the role of self-directed trans people’s voices here.

A strength of this review was the informal consultation exercise at the Trans Pregnancy conference where we were able to share early findings with academics, healthcare providers, and trans and non-binary parents. This allowed us to refine our analysis and become more sensitive to nuances related to the complexities of dysphoria. Additionally, we were able to confirm that our search strategy had effectively identified relevant literature and although further studies, including the Trans Pregnancy Project (ESRC grant ES/N019067/1), had explored relevant topics, their findings about birth experiences and PMH were not yet published.

Conclusion

Existing literature suggests factors such as dysphoria, isolation, and exclusion, and poor care may make transgender and non-binary parents more vulnerable to PMH difficulties and traumatic birth. However, trans and non-binary parents’ PMH experiences remain under-researched. There are indications that without better information and awareness amongst parents and professionals, there may be distinct barriers to identifying PMH needs and accessing relevant support.

Without the ability to accurately record gender data within perinatal services, robust assessments of prevalence rates and longevity of specific diagnosable conditions will remain difficult to obtain; potential inequalities will remain hidden, and the ability to commission or adapt services to meet local needs will be limited. Voices of trans and non-binary people are needed in PMH research to inform future services and improve outcomes for all parents and families.

Funding Statement

The first author was supported by an ESRC Fellowship [grant no. ES/T006099/1]. The second author conducted a portion of the research at the University of Leeds, UK.

Note

Although quality assessment did not form part of eligibility assessment, one paper (Lothstein, L.M., 1988, Female-to-male transsexuals who have delivered and reared their children, Annals of Sex Research, 1, 151–166) was excluded on ethical grounds. In reporting the perinatal experiences of trans men, the author referred to the participants as women, using female pronouns throughout. In addition, the author underlying assumption positioned being transgender as a mental disorder and reported a psychiatric diagnosis for each of the participants. Given the author evident biases, it seemed questionable whether the points represented the participants perspectives.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics

Ethical review was not required due to this being a review.

References

- Andersen, L. B., Melvaer, L. B., Videbech, P., Lamont, R. F., & Joergensen, J. S. (2012). Risk factors for developing post‐traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: A systematic review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(11), 1261–1272. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, J. S., Patel, A. J., Marshall, I., & Bachmann, G. A. (2019). Transgender men, pregnancy, and the “new” advanced paternal age: A review of the literature. Maturitas, 128, 17–21. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, E. E., Sedov, I. D., & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M. (2016). Prevalence of paternal depression in pregnancy and the postpartum: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 206, 189–203. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charter, R., Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., & Robinson, K. (2018). The transgender parent: Experiences and constructions of pregnancy and parenthood for transgender men in Australia. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(1), 64–77. 10.1080/15532739.2017.1399496 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnocka, J., & Slade, P. (2000). Prevalence and predictors of post‐traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 39(1), 35–51. 10.1348/014466500163095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro-Peraza, M., Garcia-Acosta, J. M., Delgado-Rodriguez, N., Sosa-Alvarez, M., Llabres-Sole, R., Cardona-Llabres, C., & Lorenzo-Rocha, N. (2019). Biological, psychological, social, and legal aspects of trans parenthood based on a real case - A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 925. 10.3390/ijerph16060925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S. A., Wojnar, D. M., & Pettinato, M. (2015). Conception, pregnancy, and birth experiences of male and gender variant gestational parents: It’s how we could have a family. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 60(1), 62–69. 10.1111/jmwh.12213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Herman, J. L., Harrison, J., & Keisling, M. (2010). National Transgender Discrimination Survey Report on health and health care. National Center for Transgender Equality. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–98. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, M., Jomeen, J., & Glover, L. (2016). What is traumatic birth? A concept analysis and literature review. British Journal of Midwifery, 24(4), 254–267. 10.12968/bjom.2016.24.4.254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, M., Sheran, N., Weber, S., Cohan, D., & Obedin-Maliver, J. (2019). Providing patient-centered perinatal care for transgender men and gender-diverse individuals: A collaborative multidisciplinary team approach. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 134(5), 959–963. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffkling, A., Obedin-Maliver, J., & Sevelius, J. (2017). From erasure to opportunity: A qualitative study of the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy and recommendations for providers. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(Suppl 2), 332. 10.1186/s12884-017-1491-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B. A., Pierre Bouman, W., Haycraft, E., & Arcelus, J. (2019). Mental health and quality of life in non-binary transgender adults: A case control study. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 251–262. 10.1080/15532739.2019.1630346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, M., Bunch, K., Tuffnell, D., Shakespeare, J., Kotnis, R., Kenyon, S., & Kurinczuk, J. J. (Eds.); On behalf of MBRRACE-UK. (2019). Saving lives, improving mothers’ care - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2015–17. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, C. A., Gold, K. J., Flynn, H. A., Yoo, H., Marcus, S. M., & Davis, M. M. (2010). Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(1), 5–14. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach, L. S., Poyser, C., Cooklin, A. R., & Giallo, R. (2016). Prevalence and course of anxiety disorders (and symptom levels) in men across the perinatal period: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 675–686. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach, L. S., Poyser, C., & Fairweather‐Schmidt, K. (2017). Maternal perinatal anxiety: A review of prevalence and correlates. Clinical Psychologist, 21(1), 4–19. 10.1111/cp.12058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light, A. D., Obedin-Maliver, J., Sevelius, J. M., & Kerns, J. L. (2014). Transgender men who experienced pregnancy after female-to-male gender transitioning. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 124(6), 1120–1127. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, E. L., Wilchins, R. A., Priesing, D., & Malouf, D. (2002). Gender violence: Transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. Journal of Homosexuality, 42(1), 89–101. 10.1300/J082v42n01_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, T., Noel-Weiss, J., West, D., Walks, M., Biener, M., Kibbe, A., & Myler, E. (2016). Transmasculine individuals' experiences with lactation, chestfeeding, and gender identity: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16, 106. 10.1186/s12884-016-0907-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmquist, A., Jonsson, L., Wikstrom, J., & Nieminen, K. (2019). Minority stress adds an additional layer to fear of childbirth in lesbian and bisexual women, and transgender people. Midwifery, 79, 102551. 10.1016/j.midw.2019.102551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L. A., Neighbors, H. W., & Griffith, D. M. (2013). The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs women: Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(10), 1100–1106. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey, S. D., & Della Vedova, A. M. (2021). Screening for mood difficulties in men in Italy and Australia using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and the Matthey Generic Mood Questionnaire. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(2), 278–287. 10.1037/men0000227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, J., Ellis, S. J., & Eccles, F. J. R. (2017). Suicide in trans populations: A systematic review of prevalence and correlates. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(3), 341–353. 10.1037/sgd0000235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock, L., & Lewis, T. K. (2008). Trauma in transgender populations: Risk, resilience, and clinical care. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 8(3), 335–354. 10.1080/10926790802262523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NICE . (2014). Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Clinical management and service guidance. NICE clinical guideline 192. NICE. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan, A., Alcorn, K. L., Patrick, J. C., Creedy, D. K., Dawe, S., & Devilly, G. J. (2014). Predicting posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth. Midwifery, 30(8), 935–941. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obedin-Maliver, J., & Makadon, H. J. (2016). Transgender men and pregnancy. Obstetric Medicine, 9(1), 4–8. 10.1177/1753495X15612658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, R. (2019). If a man gives birth he’s the father. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/if-a-man-gives-birth-hes-the-father-the-experiences-of-trans-parents-124207

- Riggs, D. W., Power, J., & von Doussa, H. (2016). Parenting and Australian trans and gender diverse people: An exploratory survey. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(2), 59–65. 10.1080/15532739.2016.1149539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roller, C. G., Sedlak, C., & Draucker, C. B. (2015). Navigating the system: How transgender individuals engage in health care services. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(5), 417–424. 10.1111/jnu.12160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L. E., Steele, L., & Sapiro, B. (2005). Perceptions of predisposing and protective factors for perinatal depression in same-sex parents. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 50(6), e65–e70. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade, P. (2006). Towards a conceptual framework for understanding post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth and implications for further research. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 27(2), 99–105. 10.1080/01674820600714582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soet, J. E., Brack, G. A., & DiIorio, C. (2003). Prevalence and predictors of women’s experience of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth, 30(1), 36–46. 10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroumsa, D., Roberts, E. F. S., Kinnear, H., & Harris, L. H. (2019). The power and limits of classification - A 32-year-old man with abdominal pain. The New England Journal of Medicine, 380(20), 1885–1888. 10.1056/NEJMp1811491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toohill, J., Fenwick, J., Gamble, J., & Creedy, D. (2014). Prevalence of childbirth fear in an Australian sample of pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 275. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, H., Harrop, D., Walton, E., Young, A., & Soltani, H. (2019). A systematic review of ethnic minority women's experiences of perinatal mental health conditions and services in Europe. PLoS One, 14(1), e0210587. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, K. (2018). Gender identity: A brief for perinatal nurses. MCN American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 43(5), 291. 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe-Roubatis, E., & Spatz, D. L. (2015). Transgender men and lactation: What nurses need to know. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 40(1), 30–38. 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]