Abstract

Objective

To develop and pilot test a palliative care intervention for family caregivers of children with rare diseases (FAmily-CEntered pediatric Advance Care Planning-Rare (FACE-Rare)).

Methods

FACE-Rare development involved an iterative, family-guided process including review by a Patient and Family Advisory Council, semistructured family interviews and adaptation of two evidence-based person-centred approaches and pilot testing their integration. Eligible families were enrolled in FACE-Rare (the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) Approach Paediatric sessions 1 and 2; plus Respecting Choices Next Steps pACP intervention sessions 3 and 4). Satisfaction, quality of communication and caregiver appraisal were assessed.

Results

Parents were mean age 40 years, and children 7 years. Children’s diseases were rare enough that description would identify patients. All children were technology dependent. Telemedicine, used with four of seven families, was an effective engagement strategy and decreased subject burden. Families found FACE-Rare valuable following a strategy that first elicited palliative care needs and a support plan. Eight families were approached for pilot testing. Of the seven mothers who agreed to participate, six began session 1, and of those, 100% completed: all four FACE-Rare sessions, baseline and 2-week postintervention assessments, and a written pACP which described their preferences for medical decision-making to share with their providers. 100% reported FACE-Rare was helpful. The top three CSNAT concerns were: knowing what to expect in the future, having enough time for yourself and financial issues. Benchmarks were achieved and questionnaires were acceptable to parents and thus feasible to use in a larger trial.

Conclusions

FACE-Rare provides an innovative, structured approach for clinicians to deliver person-centred care.

INTRODUCTION

Paediatric patients with rare diseases represent a significant proportion of those with life-limiting illnesses in paediatric hospitals.1 Family caregivers (herein referred to as ‘families’) are expected to provide a level of care once reserved for hospitals.2 Due to the uncertainty surrounding a rare disease prognosis, including the likelihood of parents being asked to make complex medical decisions for their child during medical crises, rare diseases exact a severe emotional toll on families.2 Pediatric Advance Care Planning (pACP), a key component of paediatric palliative care, is a person-centred decision-making process which involves reflection, understanding and discussion about goals of care and future medical care choices, before a medical crisis.3 As with all complex chronic conditions,4 children with rare diseases have less predictable clinical trajectories, which may contribute to disparities in intensity of inpatient end-of-life care for these conditions. The gap in pACP and end-of-life care conversations may be contributing to higher intensity end-of-life care.5 Furthermore, children with rare diseases have been excluded from palliative care research due to their heterogeneity and comorbidities,6 thereby contributing to health disparities. Available research lacks scientific rigour.7–18 Few interventions exist to ease the suffering of these families19 or to support communication about end-of-life treatment preferences. Only one empirically validated intervention exists to address these challenges: a 5-day government-supported residential Swedish intervention which empowers parents to manage their child’s rare disability,19 but does not address pACP.

To determine if families wanted to participate in a pACP process, and, if so, how, two models were considered. The first model, tailored for the population of adolescents living with HIV and cancer, the Family-Centered (FACE) pACP, incorporates Respecting Choices Next Steps (NS) pACP conversation.20 FACE pACP demonstrated increased communication about end-of-life treatment preferences; decreased disease-specific symptoms21; and improved patient and family satisfaction, even as conversations elicited strong emotions.22 The second model is the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) Approach, tailored for adult family caregivers.23–25 This person-centred/family-guided approach facilitates families’ prioritisation of their needs in the caregiving role. Adult trials demonstrated significant reductions in family strain,23–25 initiation of ACP conversations,26 adequacy of end-of-life support and achievement of preferred place of death.27 However, clinicians may be reluctant to introduce pACP for children with life-limiting conditions, fearing families will not be comfortable talking about pACP.28

For a number of reasons, the FACE pACP model needed further development. First, the proposed adaptation targets family caregivers, not adolescent patients. Second, this adaptation is for children with ultrarare diseases who are unable to communicate their treatment preferences. Third, there are legal protections in the USA on the completion of advance directives by parents of physically disabled persons and associated ethical challenges.29 Fourth, as will be discussed, families indicated they did not want to participate in pACP until after prioritised palliative care needs were met. Fifth, families of children with rare diseases often have extensive experience making decisions for their children, unlike families from our previous studies. Sixth, the ultimate goal is family-caregiver outcomes, particularly the effect of the intervention on family caregiver strain, given high caregiver strain is associated with higher overall mortality for family caregivers of older adults.30

Objectives were: (1) to develop/adapt a pACP intervention for families of children with rare diseases through a community-based participatory process; (2) to elucidate family-identified palliative care needs; and (3) to pilot test the feasibility and acceptability of an integrated FACE-Rare pACP intervention.

METHOD

Phase I: consultation with key stakeholders

The adaptation and development of the FACE-Rare intervention began by using an iterative process which included a review of the scientific literature, interviews with key stakeholders and adaptation and integration of two existing evidence-based programmes (the CSNAT Approach and the Respecting Choices NS pACP conversation) to meet the family-identified needs.

Patient and Family Advisory Council

In October 2016, the first author (MEL) requested permission to present and discuss a proposal to study pACP with families of children with rare diseases at the Patient and Family Advisory Council (P-FAC) at Children’s National’s monthly meeting. P-FAC members included families whose children have been or are being treated at Children’s National, as well as staff members who partner to provide patient and family-centred care. P-FAC members were asked if pACP was appropriate for this patient population and families. They were particularly interested in the impact on access to pACP for all children and families. Three parents of children with a rare disease from P-FAC volunteered to meet with the first author to complete open-ended interviews conducted at a later date.

National Organization for Rare Diseases

Next, the Director for National Organization for Rare Diseases was contacted and connected us with two members who volunteered to provide feedback about adapting FACE pACP. An open-ended telephone conference call was conducted; the participants were enthusiastic about the value of proactive, non-crisis-driven pACP and goals of care conversations, and offered to assist with the creation of information tools.

Myelin Disorders Clinic at Children’s National

A convenience sample of two consecutive families whose child met eligibility criteria were asked by their physician during a clinic visit if they would be interested in meeting with the first author about a research project. Both families agreed to be interviewed that day. Face-to-face unrecorded, semistructured interviews indicated resistance to participating in pACP, until other palliative care needs were met. Families were visibly overwhelmed and appeared terrified about their child’s future quality of life. These consultations revealed the importance of addressing family-prioritised needs prior to pACP. Consistent with findings in the literature, families wanted a gradual approach to pACP, which keeps all options open.31 Semistructured interviews with three P-FAC families confirmed these findings.

Phase II: programme development

Family palliative care needs assessment

A literature review identified only one evidence-based caregiver needs assessment process, the CSNAT Approach for adult family caregivers.23–27 CSNAT adopts a screening format structured around 14 broad support domains. These domains fall into two distinct groups: those that enable the caregiver to care; and those that enable more direct support for caregivers. Four response options indicate the extent of support requirements, from ‘no more’ to ‘very much more.’ The CSNAT Approach has five stages outlined in table 1, sessions 1 and 2. We invited four families who have a child with a rare disease, two patient care advocates and two employees, and a clinical psychologist with expertise in the field to review the CSNAT for its appropriateness for paediatrics. Each was sent a copy of the tool by email for review. A conference call was scheduled to discuss the recommended changes. Two modifications were made. The word ‘relative’ was changed to ‘child’; and two items were added: ‘…taking care of others in the home (eg, siblings, aging parents and grandparents)’ and ‘strengthening/ preserving your relationship with your spouse or partner’. This increased the number of items from 14 to 16. On stakeholder revision approval, the changes were discussed with the CSNAT developers who approved the changes. Investigators received a license to test the CSNAT Paediatric, a pretraining materials and a 5-hour webinar training led by the CSNAT developers.24

Table 1.

Description of Family-Centered (FACE) Pediatric Advance Care Planning (pACP)-Rare

|

Session 1:

Foundation The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT)Approach Paediatric. The pCSNAT Approach is a family caregiverled, practitioner-facilitated, validated approach to decreasing caregiver burden, tested in randomised clinical trials with adults in the UK and Australia and adapted here for family caregivers of children with rare diseases. |

Session 1: Goals Using a screening format structured around 14 broad support domains. Each domain represents a core family caregiver support domain and these domains fall into two distinct groupings: 1. To identify domains that enable the caregiver to care. 2. To identify domains that enable more direct support for caregivers. |

Session 1:

Process Stage 1. Trained facilitator orients the family to the CSNAT, which is introduced to the family caregiver by the facilitator. Stage 2: The family is given time to consider in which domains they require more support. Stage 3: An assessment conversation takes place where the facilitator and family discuss the domains for which more support is needed to clarify the specific needs of the family caregiver and their priorities. Stage 4: A shared support plan is made in which the family caregiver identifies the type of input they would find helpful. An action plan is created. |

|

Session 2:

Foundation Review of action plan for prioritised support need to gain the caregiver’s perspective. |

Session 2: Goals For the family caregiver: 1. Makes process of assessment visible. 2. Legitimises support for the caregiver. 3. Engages caregivers in the assessment process, tailoring support to their needs. For the patient: 1. Supports the caregiver who is then more likely to be able to support the patient. For the practitioner: 2. Reduces likelihood of ‘crisis management’. 3. Helps with ‘expectation management’ about what support is and is not available. For the organisation: 1. Provides a clear record of activity in relation to caregiver assessment and support; useful for auditing. 2. Shows organisational commitment to caregivers. |

Session 2:

Process Stage 5: Review of action plan for prioritised support need and reassessment of caregiver’s support needs if beneficial, for example, change in child’s condition. Facilitator actively listens, acknowledges and understands difficulties and challenges with unmet needs. Facilitator logs in unmet needs in organisation. Facilitator validates feelings of powerlessness and frustration. Acknowledge there may not be resolutions at this moment. Resource sharing. Increase awareness of being supported. Active listening is part of action plan/support. |

|

Session 3:

Foundation Respecting Choices Next Steps pACP Interview, adapted for families of children with rare diseases whose child cannot communicate. |

Session 3: Goals 1. To facilitate conversations and shared decisionmaking between the parent and support person about ACP, providing an opportunity to express fears, values, hopes, beliefs and goals for future medical care. 2. To prepare the parent/guardian for future decisionmaking in the event of a medical crisis. |

Session 3:

Process Stage 1 assesses the parent’s and support person’s understanding of their child’s current medical condition, prognosis and potential complications, as well as his or her fears, concerns, hopes and experiences. Stage 2 explores the philosophy the parent and support person might have regarding planning for future medical decision-making and their understanding of the facts. Stage 3 briefly reviews the rationale for future medical decisions the parent/ legal guardian has considered to further understanding and to build capacity to empower parents as advocates for their child. |

|

Session 4: Foundation The Respecting Choices Pediatric Advance Care Planning is a document that helps the parent(s) express how they want their seriously ill child to be treated in the event of a future medical crisis. |

Session 4: Goals To let the treatment team know: 1. The kind of medical treatment the parent(s) want or do not want for their child with a rare disease. 2. How comfortable the parent(s) want their child to be. 3. How the parent(s) want the treatment team to treat their child. 4. What parent(s) want physicians to know about their child. |

Session 4:

Process Stage 4 uses the previous conversation to clarify goals for life-sustaining preferences and complete the paediatric advance care plan. Stage 5 summarises the value of the previous discussion, as well as the need for future discussions as situations and preferences change. Remaining questions or gaps in information regarding health condition/care/treatment options are identified and the family is referred to the physician or resources. Processes, such as labelling feelings and concerns, as well as finding solutions to any identified problem, are facilitated. Stage 6 develops a follow-up plan based on caregiver’s specific needs, for example, makes a list of questions for physician. Encourages discussion with other family members. Makes appropriate referrals to help resolve conflicts over decision-making (eg, a hospital ethicist or their doctor) or spiritual issues (eg, a hospital chaplain or their clergy). Creates or makes changes to an existing advance directive. |

Goals of care conversations and pACP

These same four families and two rare disease physicians reviewed the Respecting Choices NS pACP conversation, which was developed, pilot tested and implemented at a large mid-western health system with parents of children with life-limiting illnesses.20 This new application resulted in updated conversation guide language and the use of a pACP document which maintains the original five stages outlined in table 1, sessions 3 and 4. The pACP document and conversation guide have not been empirically tested. Due to the complexities surrounding the protection of disabled children,29 this pACP document was reviewed and approved by legal counsel and clinical experts. Modifications made to the pACP document by families included: adding instructions for providers; replacing the term ‘in the event of a serious complication’ with ‘medical crisis’; adding goal statements to each option with additional space to write instructions specific to their child; and adding an option to include preferred place of death. Lastly, the pACP conversation was divided into two sessions to give the families a chance to reflect on the pACP document.

The adapted FACE-Rare model

Implemented either in person or via telemedicine, the goals and processes of the integrated four-session FACE-Rare intervention are outlined in table 1. Sessions 1 and 2 focused on caregiver needs, using the CSNAT Paediatric. In session 1, caregivers rated their needs across 16 domains, ranked the three highest priority needs and developed a shared action plan to address those needs with the facilitator. In session 2, caregivers debriefed with the facilitator to discuss the process and barriers. Session 3 used the Respecting Choices NS pACP conversation to discuss caregivers’ life experiences, values and beliefs, and goals of care for future healthcare decisions. Session 4 provided the opportunity to create a written plan for their child, which could be shared with the primary care team and included in the child’s medical record. Sessions 3 and 4 were videotaped for fidelity purposes and transcribed by volunteer graduate students for qualitative analysis.

We then tested the combined integration of these two validated interventions. FACE-Rare families participated in four 45–60 min sessions scheduled approximately 1 week apart. Attendance was recorded. Enrolled participants did not receive any monetary or other compensation.

Phase III: feasibility and acceptability

Pilot testing of FACE-Rare was conducted from October 2017 to January 2018 by trained facilitators using a pre-post test design. We identified eight potential families from the Complex Care Program of Children’s National who met the initial eligibility criteria. Child inclusion criteria were: diagnosed with a rare disease; ages ≥1 year ≤21 years; not in foster care; unable to participate in healthcare decision-making; waiver of assent; consent from legal guardian; and not diagnosed with autism, cancer, cystic fibrosis, Down syndrome, HIV, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, sickle cell disease and rare paediatric cancers. The latter disorders were excluded because disease-specific interventions are available. Inclusion criteria for families were: legal guardian and family caregiver of child with rare disease as defined above; aged 18 years or older; ability to speak and understand English; absence of severe depression,32 33 active homicidality,33 suicidality,33 or psychosis33 determined at baseline screening; not known to be developmentally delayed; signed waiver of assent for their child; and consent to participate. Families were encouraged to bring a support person with them.

Measures

Immediately following each session, satisfaction and quality of communication questionnaires were administered by an investigator, who was not a facilitator. Outcome measures were administered at baseline and approximately 2 weeks after intervention.

Demographic data form was administered by a trained investigator to obtain family-reported sociodemographic information. Medical data were obtained from data abstraction of the electronic health record.

Primary outcome

Family Appraisal of Caregiving Questionnaire for Palliative Care.34 Family caregiver’s self-report of caring for the child/patient in the past 2 weeks. There are four subscales. Two subscales, Caregiver Strain and Caregiver Distress, have proven sensitive to the CSNAT intervention in adults.25 26 Scores on this subscale have excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.86). Twenty-five items.

Process outcomes

Satisfaction Questionnaire was developed for the FACE study22 and was administered immediately after all four sessions. Items rated responses to each session, such as ‘hurtful’ or ‘worthwhile’ on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’. Higher scores indicate higher satisfaction. Thirteen items.

Curtis’s Quality of EOL Communication Questionnaire35 evaluated the quality of communication regarding FACE-Rare between the family and the facilitator. The revised 5-item questionnaire was used.36 Four items determine the quality of family–facilitator communication, rated on a 3-point Likert scale from ‘No’ to ‘Definitely Yes’. The fifth item asks for an overall evaluation of the participant’s satisfaction with the quality of communication with the facilitator. Higher scores indicate higher quality of communication. Good internal reliability has been reported (Cronbach’s α=0.81).36 Five items.

Analysis

Data were entered into a REDCap data base. Data were summarised using descriptive statistics, as significance testing was not feasible. These characterised demographic data, per cent enrolment, attendance, retention and completeness of data. Means and range for study questionnaires were calculated at baseline, immediately after session and approximately 2 weeks after intervention. Family-identified primary palliative care needs collected during session 1 were written down at the time of the interview by the facilitator onto a standardised CSNAT form. A support action plan was then created by the family and written down by the interviewer onto a standardised form to be reviewed during session 2. Interview data from sessions 3 and 4 were videotaped, transcribed, deidentified and are currently being analysed qualitatively for future publication.

RESULTS

Participants

All initially eligible families were approached (n=8). Target enrolment was 10, but we stopped enrolment for lack of time and resources. One mother declined and one was lost to follow-up after baseline assessment. No one was excluded from participation because of ineligibility. Six families completed the four-session intervention and follow-up session. Two mothers brought the child’s father as a support person for the completion of goals of care conversation and pACP document, and their child was present for most of the interview. In two cases sessions 3 and 4 were combined into one study visit, per family request.

Parents were aged 30–50 years with a mean age of 40.4 (SD=7.7), 100% female, 57% Caucasian, 43% income equal to or lower than the federal poverty level and 71% married. Children were aged 2–12 years with a mean age of 6.7 years (SD=4.0). Children’s diseases were rare enough that description would identify patients. Six of the seven children had seizure-related disorders. See table 2 for technology dependency details.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for technology dependency (n=7)*

| Participant ID | Wheelchair | Breathing machine | Feeding tube/pump | Central lines (Total Parenteral Nutrition) | Other | Specify for Other | Total number of technology dependency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 001–1 | Yes | 1 | |||||

| 002–1 | Yes | 1 | |||||

| 003–1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Intermittent straight catheterisations | 3 | ||

| 004–1 | None | 0 | |||||

| 005–1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Baclofen pump, hearing aid | 3 | ||

| 006–1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 | |||

| 007–1 Yes Yes 2 | Yes | Yes | 2 | ||||

Mean age of 6.7 years (range 2–12).

Benchmarks

We achieved the predetermined benchmarks: ≥50% enrolment of eligible families, 86% enrolled; ≥80% attendance, 100% of those who started session 1 completed all four sessions; and ≥85% retention, 86% of families completed the 2-week follow-up assessments. All six families also completed a written pACP, describing in detail their current preferences for medical decision-making should their child have a critical health event. Families were encouraged to share the written pACP with their child’s healthcare team.

Palliative care needs and family-initiated support plan

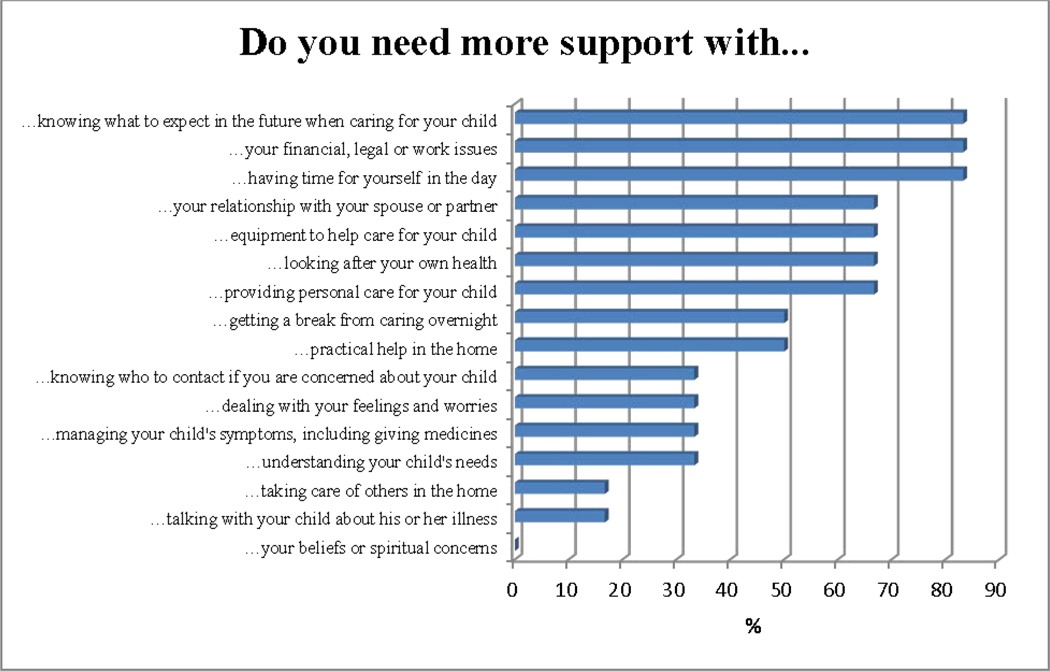

Priority palliative care needs were rank ordered from highest to lowest on the CSNAT. The top three concerns were: knowing what to expect in the future, having time to yourself and financial issues (see figure 1). Numbers are too small to explain meaningfully by other criteria. During the CSNAT session, the facilitator provided support and information, and discussed the family-identified concerns. Families were asked to prioritise two to three domains and create an action plan. Approximately 2 weeks later, families returned, or were contacted through telemedicine, to review their action plan. See table 3 which describes the family-identified priorities, action plan and plan review. Qualitative data were also captured. Families stated they were ‘living on the precipice’ and in a state of ‘perpetual grief’. They were isolated from earlier social supports, such as their church, as their child lived years longer than the original prognosis, and the level of social supports initially provided could not be sustained. All regarded themselves as experts in the care of their children.

Figure 1.

The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) family caregiver/legal guardian: percentage of participants with needs (n=6).

Table 3.

CSNAT Approach Paediatric: support plan for prioritised needs of family caregivers

| PID | Domain priority 1 | Support need in relation to prioritised domain (session 1) | Agreed action plan to address support need | Review of plan (session 2) | Domain priority 2 | Support need in relation to prioritised domain (session 1) | Agreed action plan to address support need | Review of plan (session 2) | Domain priority 3 | Support need in relation to prioritised domain (session 1) | Agreed action plan to address support need | Review of action plan (session 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1 | Looking after your own health | Time away from caregiving for personal needs’make myself a priority’ | Day off from work for medical appointments. Look for someone else to take girls to appointments. Family Medical Leave to take from work. | Relied on memory and did not look at plan. Working on preparations for daughter that has provided mental peace. | Practical help in the home | 05:00 help with child and 1 hour 21:00– 22:00 with children. Saturday alone time for naps. | Maybe care.com. A 10 year old to take on more responsibility for bedtime routine. Autism waiver for someone to come. Talk to Dad. | Dad lost his brother this week, has too much stress currently for additional help. Will reach out to care.com. | Getting a break from overnight caregiving | Childcare while awake at night | Dad to help on his days off. Continue with medication wean to get to clinical trial. | Dad maybe wiling to be open for help in the morning due to stress. Adjust autism aide hours to accommodate. |

| 2 | Understanding your child’s illness | Further education on specific items related to illness | Give some time. | Will discuss questions with Physician’s Assistant and Registered Nurse. | Having time for yourself in the day | More evening rest and weekend time | Earlier bedtime, set routine, commit to yoga. | No progress yet made | Not indicated | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | Equipment to help care for child | Improved Hoyer lift, having the manual lift, beach wheelchair, bath chair | Will talk with equipment supplier, website beach wheelchair. | Once things calm down at appointment on 28th | Getting a break from night-time care | One night Dad has monitor to listen. | Share night observation times. | Discussion completed on weekend | Your financial, legal, work issues | Veterans Administration to change payments for insurance |

Assistance with Medicaid and hospital-related insurance changes. Social work reach out to info number. | Sent out all information to listed contact. |

| 5 | Your financial, legal, work issues | Job cut back for patient’s appointments. Husband is now back to work. | Wheelchair lift for car. Home Hoyer lift, legislative outreach. | Mom found agency doing home (free) devices created by Anelents she will apply for. | Having time for yourself in the day | Needs time to get out of the house | Niece is always on vacation, when she comes back for school she will speak with her about help. | Will speak to niece about help when she comes back from vacation. | Not indicated | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 6 | Your financial, legal, work issues | Not working right now, new job, will now lose some benefits because of income. Had to leave previous job because of multiple calls for son. | Will reach out to other parents at Children’s National. Have facility, after school hours, and night care. | Reach out to patient care advocate. | Knowing what to expect in the future when caring for your child | How to deal with managing all the details of disease. Being mom and not knowing when the end may come. | Will reach out to PANDA+HELP team if needed. Will talk with doctors as a support system. Turned down hospice too negative. | Appointment with PANDA Palliative Care Team today which was helpful | Not indicated | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | Having time for yourself in the day | No way to get out of the house. Has a waiver for healthcare aid. | Use randomly Dad for visits. Health aide. Respite programme every other Sunday. | Dad came Monday and Mom got some time out. Will use respite Sunday to see StarWars. | Looking after your own health (physical problems) | Forgot to schedule any appointments for self | Recently scheduled some appointments | One appointment missed, will call back. More appointments to come. | Not indicated | N/A | N/A | N/A |

PID 004 withdrew at baseline.

CSNAT, Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool; N/A, not applicable; PID, participant ID.

Satisfaction and quality of communication

Ratings of each session (n=26 ratings) indicated sessions were helpful (100%) and useful (100%) for all families. Sessions were also emotionally intense for some, for example, scary (8%) or sad (27%). None reported finding any of the sessions harmful. See table 4. Quality of communication ratings between the facilitator and the family caregiver were very high for all sessions. All felt the facilitator cared about them, although not necessarily that their attitudes were known by the facilitator (see table 4). An exemplar quote following session 2: ‘I felt she [facilitator] was encouraging and validated work I started to reach my goals. It’s not often you hear the encouragement.’

Table 4.

Individual item Satisfaction Questionnaireand quality of communication results for FACE-Rare pACP intervention with families of children with ultrarare diseases (n=7)*

| Family caregiver responses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Session 1 Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) (n=6) | Session 2 CSNAT support action plan (n=6) | Session 3 Respecting Choices Next Steps goals of care conversation (n=7) | Session 4 Respecting Choices Pediatric Advance Care Planning (n=7) | |

|

|

||||

| Satisfaction | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|

| ||||

| It was useful† | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| It was helpful† | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| I felt scared or afraid† | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| It felt like a load off my mind† | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) |

| It was too much to handle† | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| I felt satisfied† | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (71.4) | 6 (85.7) |

| It was harmful† | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| I felt angry† | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| It was something I needed to do† | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| I felt sad† | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (28.6) |

| I felt courageous† | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 4 (57.1) | 4 (57.1) |

| It felt hurtful† | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| It was worthwhile† | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 6 (85.7) | 7 (100.0) |

| Quality of communication | ||||

| 1. Do you think that your attitudes are known by the interviewer?‡ | 5 (83.3) | 6 (100.0) | 5 (71.4) | 6 (85.7) |

| 2. Did you feel that the interviewer cared about you as a person?‡ | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| 3. Did you feel that the interviewer listened to what you said?‡ | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| 4. Did you feel that the interviewer gave you enough attention?‡ | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) |

| 5. How would you rate the overall quality of the discussions you just had with the interviewer?§ | 6 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) |

One father completed the process measures.

Agree or strongly agree.

Probably yes or definitely yes.

Good, very good, or excellent.

FACE-Rare, Family-Centered Pediatric Advance Care Planning-Rare.

Caregiver appraisal

Mean positive caregiver appraisal increased from 4.5 (range 3.6–5.0) to 4.7 (range 3.9–5.0). Family well-being increased from 3.9 (range 2.5–4.7) to 4.1 (range 3.2–5.0). Mean caregiver strain increased from 3.1 (range 1.4–4.3) to 3.6 (range 2.8–4.3). Mean caregiver distress increased from 2.5 (range 1.3–4.0) to 2.9 (1.8–4.3) at 2 weeks after intervention. The sample size is too small to interpret.

Future iteration

Families recommended combining sessions 3 and 4 into one visit with a short break, especially if this coincided with their child’s medical visit.

DISCUSSION

The development of the FACE-Rare intervention is the first step in providing a structured and individualised approach for family caregivers of children living with rare diseases. This meets the recommendations of the National Alliance for Caregiving2 to provide accessible and understandable information and to empower families in research development and adaptation to best meet self-identified needs. Families took the time and reliably completed the baseline and follow-up questionnaires, in addition to attending all FACE-Rare sessions. Study participation was not too burdensome, despite interruptions by alarms from the children’s technology. The adaptation of the sessions to be culturally sensitive through an iterative process of community review and involvement of consumers, key stakeholders and experts was successful. Training and certification were successful. pCSNAT results were consistent with findings in the adult motor neuron disease setting,25 where family caregivers reported gaining a sense of empowerment and a high priority for ‘knowing what to expect in the future.’ Future clinical trials will benefit from innovative data analytical techniques, which make it feasible37 to study this heterogeneous group of children. Such a seemingly difficult topic to broach was facilitated by the CSNAT process of regular conversations in the present study as well, as all families completed pACP following the CSNAT Approach.

One facilitator experienced a sense of powerlessness during the interviews and another was moved to tears, because of the depth of unmet needs and the difficult circumstances. Yet, families reported the experience useful and helpful, suggesting the FACE-Rare intervention provided families with visibility of support needs and gave legitimacy and permission to ask for help. Families felt cared about as assessed by the quality of communication questionnaire. This process likely increased readiness to participate in pACP, which itself provided some control in a low-control situation (empowerment), consistent with the studies’ conceptual framework of transactional stress and coping through problem solving.38 Support for clinicians to cope with the emotional intensity of this work needs to be integrated into the model.

Study outcomes include a structured curriculum and training protocol. High medical care needs, frequent appointments and demanding family caregiving make it difficult to make the time for these discussions. Telemedicine, used with four of seven families, served as an effective engagement strategy and decreased subject burden. African-American fathers participated in creation of pACP. This is significant, as African-American male caregivers are rarely studied.39 Future studies should identify additional ways to encourage fathers or other support persons to be present for goals of care conversations and creation of pACPs.

FACE-Rare may fill the gap in pACP for families whose child has benefited from enhanced life-extending technology which has postponed the death of their ‘terminal’ child into adolescence. This is congruent with mortality data for non-cancer complex chronic condition-related deaths in the USA.40 This window provides the opportunity to explore the values and preferences of families during the interim to make decisions regarding goals and limits of care for their child40; and to communicate these plans to the healthcare team. FACE-Rare thus provides an innovative, structured approach for clinicians to deliver person-centred care.

This study has limitations. The sample size is too small to make any inferences, but is appropriate for pilot testing. Selection bias existed by identifying families who might be interested in pACP, which can be addressed in a future randomised trial. The follow-up period for the CSNAT was too short to have enough time to put supports in place to alleviate the strain of parents. In clinical practice, clinicians can make the call about the best timing for follow-ups. Results are not generalisable. Target enrolment for pilot testing was 10 families, but resource limitations precluded this. Facilitators were expert nurses, so the facilitator skill set may not generalise. However, previous experience with training facilitators suggests it is realistic to certify interested facilitators to competency criteria.

CONCLUSIONS

Families found pACP conversations helpful, following a family-recommended strategy of first eliciting palliative care needs and creating a support plan. We are currently conducting research using the pCSNAT in a paediatric palliative care setting in Australia, which includes clinicians’ perspectives on the process. Research on FACE-Rare is needed (1) to assess the feasibility in a pilot randomised controlled trial (n=30 families); (2) to estimate the likely impact on caregiver outcomes; and (3) to study its value for strengthening clinician resiliency. If successful, an international randomised trial is planned. Concurrently, clinicians could use the pCSNAT as preparation for pACP conversations with parents about values and goals of care for their child when not in a medical crisis.

Acknowledgements

We give deep thanks to our study participants for helping us. We also thank the following people for their work on this study: the faculty and staff from the Center for Translational Science/Children’s Research Institute, including Dr Lisa Guay-Woodford; and Special Volunteers Christopher Lin and Jessica Livingston. We also thank Dr Gail Ewing of the Centre for Family Research, University of Cambridge, who trained the CSNAT paediatric facilitator, and Dr Janet Diffin, Queen’s University, Belfast Medical Biology Centre, who also trained the CSNAT paediatric facilitator.

Funding Research reported in this publication received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. MEL used her Center for Translational Science departmental academic fund to support this research.

Footnotes

Competing interests LB is the cocreator of the Respecting Choices Next Steps ACP intervention. She receives a small royalty.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the Children’s National Institutional Review Board (protocol number 8808).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

Disclaimer The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bösch A, Wager J, Zernikow B, et al. Life-limiting conditions at a university pediatric tertiary care center: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2018;21:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Alliance for Caregiving. Rare disease caregiving in America, 2018. Available: https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/NAC-RareDiseaseReport_February-2018_WEB.pdf [Accessed 12 Dec 2018].

- 3.Lotz JD, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, et al. Pediatric advance care planning: a systematic review. PEDIATRICS 2013;131:e873–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston EE, Bogetz J, Saynina O, et al. Disparities in inpatient intensity of end-of-life care for complex chronic conditions. Pediatrics 2019;143:e20182228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. JCO 2012;30:4387–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams LS, Miller JL, Grady PA. The spectrum of caregiving in palliative care for serious, advanced, rare diseases: key issues and research directions. J Palliat Med 2016;19:698–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldbeck L, Fidika A, Herle M, et al. Psychological interventions for individuals with cystic fibrosis and their families. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;18:1–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landfeldt E, Lindgren P, Bell CF, et al. Quantifying the burden of caregiving in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol 2016;263:906–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. PEDIATRICS 2011;127:529–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelentsov LJ, Fielder AL, Laws TA, et al. The supportive care needs of parents with a child with a rare disease: results of an online survey. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelentsov LJ, Laws TA, Esterman AJ. The supportive care needs of parents caring for a child with a rare disease: a scoping review. Disability and Health Journal 2015;8:475–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins A, Hennessy-Anderson N, Hosking S, et al. Lived experiences of parents caring for a child with a life-limiting condition in Australia: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2016;30:950–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Splinter K, Niemi A-K, Cox R, et al. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and families affected by methylmalonic acidemia. J Genet Counsel 2016;25:936–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeKoven M, Karkare S, Lee WC, et al. Impact of haemophilia with inhibitors on caregiver burden in the United States. Haemophilia 2014;20:822–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindvall K, von Mackensen S, Elmståhl S, et al. Increased burden on caregivers of having a child with haemophilia complicated by inhibitors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:706–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brewer HM, Eatough V, Smith JA, et al. The impact of Juvenile Huntington’s Disease on the family: the care of the rare childhood condition. J Health Psychol 2008;13:5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waisbren SE et al. Brief report: predictors of parenting stress among parents of children with biochemical genetic disorders. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2004;29:565–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Global Genes. Rare disease impact report: insights from patients and the medical community, 2013. Available: https://globalgenes.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/ShireReport-1.pdf [Accessed 10 Jan 2017].

- 19.Dellve L, Samuelsson L, Tallborn A, et al. Stress and well-being among parents of children with rare diseases: a prospective intervention study. J Adv Nurs 2006;53:392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammes BJ, Klevan J, Kempf M, et al. Pediatric advance care planning. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2005;8:766–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyon ME, Garvie PA, D’Angelo LJ, et al. For the adolescent palliative care consortium. advance care planning and HIV symptoms in adolescence. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20173869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dallas RH, Kimmel A, Wilkins ML, et al. A randomized controlled trial of of FAmily-CEntered (face) advanced care planning for adolescents with HIV/AIDS: emotions, acceptability, feasibility. Pediatr 2016;138:363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aoun S, Toye C, Deas K, et al. Enabling a family caregiverled assessment of support needs in home-based palliative care: potential translation into practice. Palliat Med 2015;29:929–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewing G, Brundle C, Payne S, et al. The carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: a validation study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2013;46:395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aoun SM, Deas K, Kristjanson LJ, et al. Identifying and addressing the support needs of family caregivers of people with motor neurone disease using the carer support needs assessment tool. Palliat Support Care 2016:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aoun SM, Grande G, Howting D, et al. The impact of the carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) in community palliative care using a stepped wedge cluster trial. Plos One 2015;10:e0123012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aoun SM, Ewing G, Grande G, et al. The impact of supporting family caregivers before bereavement on outcomes after bereavement: adequacy of end-of-life support and achievement of preferred place of death. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2018;55:368–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanderson A, Hall AM, Wolfe J. Advance care discussions: pediatric clinician preparedness and practices. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2016;51:520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vose LA, Nelson RM. Ethical issues surrounding limitation and withdrawal of support in the pediatric intensive care unit: ethical issues surrounding limitation and withdrawal of support in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med 1999;14:220–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkins M, Howard VJ, Wadley VG, et al. Caregiving strain and all-cause mortality: evidence from the REGARDS study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 2013;68:504–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beecham E, Oostendorp L, Crocker J, et al. Keeping all options open: Parents’ approaches to advance care planning. Health Expect 2017;20:675–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. 2nd edn. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace and Co, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaffer D, Schwab-Stone M, Fisher P, et al. The diagnostic interview schedule for Children-Revised version (DISC-R): I. Preparation, field testing, interrater reliability, and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32:643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper B, Kinsella GJ, Picton C. Development and initial validation of a family appraisal of caregiving questionnaire for palliative care. Psycho-Oncology 2006;15:613–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtisa JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell E, et al. The quality of patient-doctor communication about end-of-life care: a study of patients with advanced AIDS and their primary care clinicians. AIDS 1999;13:1123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2006;9:1086–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMenamin M, Berglind A, Wason JMS, et al. Improving the analysis of composite endpoints in rare disease trials. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2018;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazarus RS, Stress FS. Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz AJ, McInnis-Dittrich K. Meeting the needs of male caregivers by increasing access to accountable care organizations. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 2015;58:655–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, et al. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. PEDIATRICS 2001;107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]