Dear Editor,

Community-acquired pneumonia in critically ill elderly is associated with higher long-term mortality: patients over 80 years old (y.o.) hospitalised in the intensive care unit (ICU) for respiratory infection had a tenfold increased risk of death 6 months post-hospitalisation [1]. Noteworthy, the number of elderly patients admitted to an ICU steadily increased, likely reflecting the aging population [2]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has challenged the triage criteria for the elderly population for admission to an intensive care unit. On one hand, the ICU-bed shortage prompted to limit ICU admissions for very old patients; on the other hand, there was a risk of weighing patient age too strongly when considering treatment options. To carefully balance the treatment decisions for critically ill old patients, information on their outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection are needed. The aim of this nationwide study was to describe 6-month mortality of elderly patients (≥ 80 y.o.) after ICU admission with invasive mechanical ventilation for COVID-19.

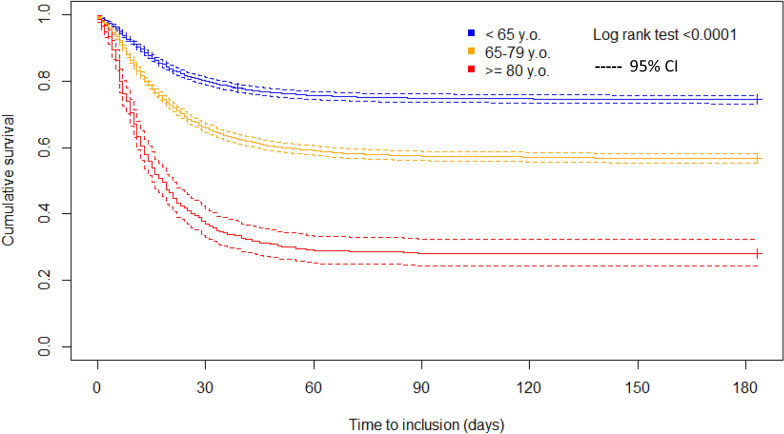

We performed a cross-sectional study using data from the French hospital discharge database (HDD), exhaustive for all public and private hospitals. Patients were included according to the following criteria: adults (≥ 18 y.o.), with invasive mechanical ventilation, admitted in ICU between 2020-03-01 and 2020–05-31, with ICD-10 diagnosis code of COVID-19. No nominative, sensitive, or personal data of patients have been collected. The main outcome was the 6-month mortality, which was defined as death during the hospital stay or during one readmission over the 6-month follow-up. We used Kaplan–Meier estimates to describe the overall mortality and log-rank test to compare patients ≥ 80 y.o. with patients 65–79 y.o. and < 65y.o.

We included 480 COVID-19 ventilated patients ≥ 80 y.o. who were compared with 4,646 and 4,759 COVID-19 ventilated patients of 65–79 y.o. and < 65 y.o., respectively. Online Table 1 reports the baseline characteristics and specific care support provided in ICU. Mortality was 62.5% during the ICU stay and 72.1% at 6 months for COVID-19 ventilated patients ≥ 80 y.o. The Kaplan–Meier curves showed important and significant differences in mortality in the elderly as compared with the younger age classes (log-rank test < 0.0001, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing the cumulative probabilities of survival, up to 6 month after ICU stay of critically ill SARS-CoV-2-infected patients with invasive mechanical ventilation

This study has limitations. First, the mortality was estimated based on at-hospital mortality. Out-of-hospital deaths were not recorded, giving a potential underestimation of the actual mortality. However, based on data from the INSEE survey [3], we know that dying people in France mostly end up in a hospital. Second, elderly individuals are admitted to ICU if a high likelihood of survival is expected a priori. Indeed, elderly patients studied here were selected from a triage based on the appropriateness of ICU admission. Overall, the mortality is likely to be underestimated in our study. Third, the study is from the “first wave”, therapeutic approaches have evolved since.

Among critically ill COVID-19 patients ≥ 80 y.o. considered as having a potential benefit from an ICU admission, we observed a 6-month mortality of 72%. This mortality rate is in the upper end of recent literature focusing on older critically ill patients [4, 5]. These findings provide data for more informed goals-of-care discussions for critically ill elderly patients infected by SARS-CoV-2.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all staffs of health care facilities who contributed to the Hospital Discharge Database implementation.

Abbreviations

- HDD

Hospital discharge database

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- SAPS II

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

- SD

Standard deviation

Author contributions

AG, LGG, LG, and EL conceived and designed the study and were involved in drafting the manuscript. LG performed the data retrieval and LG, EL, AG and LGG performed the statistical analysis. LG, EL, AG, AK, and LGG were involved in the interpretation of the data, in drafting the manuscript, and made critical revisions to the discussion section. LG, EL, AG, AK, and LGG read and approved the final version to be published.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no sources of funding for the research.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No nominative, sensitive, or personal data of patients have been collected. Our study involved the reuse of already recorded and anonymized data. The study falls within the scope of the French Reference Methodology MR-005 (declaration 2205437 v 0, august 22nd, 2018, subscripted by the Teaching Hospital of Tours), which require neither information nor consent of the included individuals. This study was consequently registered with the French Data Protection Board (CNIL MR-005 number #2018160620).

Availability of data and material

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data and so are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the institution.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Antoine Guillon, Email: antoine.guillon@univ-tours.fr.

Emeline Laurent, Email: E.LAURENT@chu-tours.fr.

Lucile Godillon, Email: L.GODILLON@chu-tours.fr.

Antoine Kimmoun, Email: akimmoun@gmail.com.

Leslie Grammatico-Guillon, Email: leslie.guillon@univ-tours.fr.

References

- 1.Guillon A, Hermetet C, Barker KA, et al. Long-term survival of elderly patients after intensive care unit admission for acute respiratory infection: a population-based, propensity score-matched cohort study. Crit Care LondEngl. 2020;24:384. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03100-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laporte L, Hermetet C, Jouan Y, et al. Ten-year trends in intensive care admissions for respiratory infections in the elderly. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:84. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.594 000 personnes décédées en France en 2016, pour un quart d’entre elles à leur domicile—Insee Focus—95. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/3134763. Accessed 4 Mar 2021

- 4.Guidet B, Vallet H, Boddaert J, et al. Caring for the critically ill patients over 80: a narrative review. Ann Intensive Care. 2018 doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0458-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cillóniz C, Dominedò C, Pericàs JM, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in critically ill very old patients: a growing problem. EurRespir Rev Off J EurRespirSoc. 2020 doi: 10.1183/16000617.0126-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.