Significance

Inequality between groups is all around us—but who tends to notice, and when? Whereas some individuals assert rampant inequality and demand corrective interventions, others exposed to the same contexts retort that their peers see certain inequalities where none exist and selectively overlook inconvenient others. Across five studies (total N = 8,779), we consider how individuals’ ideological beliefs shape their proclivity to naturalistically attend to—and accurately detect—inequality, depending on which groups bear inequality’s brunt. Our results suggest that social egalitarians (versus anti-egalitarians) are more naturally vigilant for and accurate at detecting inequality when it affects societally disadvantaged groups (e.g., the poor, women, racial minorities) but not when it (equivalently) affects societally advantaged groups (e.g., the rich, men, Whites).

Keywords: inequality, attention, politics, ideology, egalitarianism

Abstract

Contemporary debates about addressing inequality require a common, accurate understanding of the scope of the issue at hand. Yet little is known about who notices inequality in the world around them and when. Across five studies (N = 8,779) employing various paradigms, we consider the role of ideological beliefs about the desirability of social equality in shaping individuals’ attention to—and accuracy in detecting—inequality across the class, gender, and racial domains. In Study 1, individuals higher (versus lower) on social egalitarianism were more likely to naturalistically remark on inequality when shown photographs of urban scenes. In Study 2, social egalitarians were more accurate at differentiating between equal versus unequal distributions of resources between men and women on a basic cognitive task. In Study 3, social egalitarians were faster to notice inequality-relevant changes in images in a change detection paradigm indexing basic attentional processes. In Studies 4 and 5, we varied whether unequal treatment adversely affected groups at the top or bottom of society. In Study 4, social egalitarians were, on an incentivized task, more accurate at detecting inequality in speaking time in a panel discussion that disadvantaged women but not when inequality disadvantaged men. In Study 5, social egalitarians were more likely to naturalistically point out bias in a pattern detection hiring task when the employer was biased against minorities but not when majority group members faced equivalent bias. Our results reveal the nuances in how our ideological beliefs shape whether we accurately notice inequality, with implications for prospects for addressing it.

Inequality between social groups is, by some measures, hard to miss (1–5). Yet despite widespread public discussion of the persistence of inequality along economic, racial, and gender lines, there are divergent views about the extent to which it is a problem and which groups bear its brunt. These divergences reflect more than motivated reasoning anchored in individuals’ desire to advance their own class, race, or gender group interest; they are also indicative of biases in line with one’s ideological preferences. Those on the political left—who tend to value group-based equality—claim that the other side is willfully blind to inequality against groups at the bottom of society. Those on the political right—who tend to be more tolerant of group-based disparities—argue that the other side sees inequality where none exists (or where any inequality in fact harms groups at the top of society). Consider, for example, the heated exchanges about whether racial microaggressions are pervasive features of contemporary society or whether they represent trumped-up fictions by ideologically blinkered subscribers to “victimhood culture” (6).

There will likely be little progress in agreeing on how to address inequality as long as there is such disagreement regarding the extent to which it exists and who it affects. How might those on the political left and right come to such different conclusions about the extent of inequality in the world around us? Here, we propose it is because individuals’ ideological beliefs about the desirability of group-based equality shape their attention to and accuracy in detecting inequality in the first place. Drawing on and extending research on motivated processes underlying social cognition, we consider how variation in social egalitarianism—the ideological belief in the desirability of equality between groups—might shape our proclivity to notice inequality in the world around us. Whereas existing research focuses on how motivations cause us to actively evaluate, interpret, rationalize, and distort information with which we are confronted in order to fit our preexisting beliefs, our work sheds light on an upstream attentional mechanism by which the different ideologies we are committed to can lead us to experience different realities.

Existing research suggests that we are often motivated processors of information, construing the world in ways that align with and further our personal goals or those of the collectives to which we belong (7–13). Beyond individual or group-based motives, our ideological belief systems play a role in shaping our information processing too. Both gun control advocates and opponents evaluate evidence that favors their preexisting positions as more compelling than evidence that challenges them (14, 15). Individuals motivated to justify the societal status quo are less likely to remember information about climate change suggesting the need for action (16). And individuals on the political left and right interpret the same video of protestors’ behavior differently depending on whether they believe that the protestors are protesting against entities or causes they ideologically favor—restrictions on abortion or the military, respectively (17).

One ideological belief specifically relevant to inequality is social dominance orientation (SDO) (18). Individuals lower in SDO—social egalitarians—believe that all groups in society should be equal; individuals higher in SDO are more tolerant of the notion of a hierarchy of group standing in society. This difference in tolerance for group-based inequality is one of the main factors that distinguishes political liberals from conservatives (19, 20). And as with conservatism, individuals’ level of social egalitarianism (as captured by SDO) can shape their social cognition in ways that align with their respective worldviews. For example, individuals lower in SDO evaluate a newspaper article supporting affirmative action as more valid than a similar article opposing it, whereas individuals higher in SDO show the reverse pattern (21). Social egalitarians apply a more exacting standard when judging the diversity of organizations, requiring an organization to be heterogeneous on more dimensions before labeling it diverse than individuals higher in SDO (22). And highlighting a proclivity to adopt different interpretive frames, individuals high in SDO judge the same gain in power by disadvantaged groups as more dramatic than do individuals low in SDO (23).

Prior research has directly examined how individuals differ in their judgments about the degree of societal inequality (or closely related constructs) as a function of their ideological beliefs, including SDO. Some research suggests that political liberals and individuals who question the legitimacy of the status quo perceive more income and wealth inequality in society than do political conservatives and those who justify the status quo (24–26). Other research suggests that political conservatives estimate greater socioeconomic mobility than do political liberals [with some of this work arguing that liberals underestimate actual mobility and other work proposing that conservatives overestimate it (27–29)]. Focusing specifically on ideological beliefs about the desirability of equality, one paper found that individuals lower in SDO perceived larger status differences between ethnic groups (e.g., between Whites and ethnic minorities), reflective of more inequality, whereas those higher in SDO tended to perceive smaller discrepancies, minimizing inequality (30).

Still, the research noted above cannot clearly point to motivated perception as an explanation because it fails to rule out the possibility that ideology shapes abstract judgments about the degree of economic inequality in society by affecting the information people are exposed to in their daily lives rather than their processing of that information. For example, anti-egalitarians could conclude that there is less inequality in society if they happened to be less likely than egalitarians to live in areas that expose them to large discrepancies between those at the top and the bottom (31). One recent paper provided clearer evidence of differences in information processing rooted in egalitarianism (32). Across a number of studies, the authors found that individuals lower (versus higher) in SDO perceived more social inequality (measured mostly as larger gaps in power between groups at the top and bottom of the social hierarchy). Importantly, these differences emerged even when participants were exposed to and asked to evaluate identical stimuli, suggesting ideological differences in processing the same information about inequality. In one study, participants evaluated the steepness of a series of visually depicted hierarchical organizations. Social egalitarians judged the same stimuli as having steeper hierarchies than did individuals more tolerant of social hierarchy. In a subsequent surprise memory task, the authors assessed objective accuracy by presenting the previously encountered organizations beside more and less hierarchical distractors and asking participants to select which hierarchy they previously saw. Individuals higher in SDO were more likely to underestimate inequality previously encountered whereas individuals lower in SDO were (marginally) more likely to overestimate it.

Taken together, research suggests that when we’re explicitly asked to judge an aspect of the world relevant to our ideological beliefs, we sometimes apply standards, evaluate information, or adopt interpretive frames in ways that help us rationalize conclusions consistent with our ideological worldviews (as we do on behalf of ourselves and our groups). Individuals’ motivated interpretation of information is therefore one mechanism by which those on the left and right might come to disagree so strongly about whether the poor and the rich, men and women, or racial majorities and minorities are treated equally.

Here, we consider a complementary but distinct possibility. We propose that, as a consequence of our ideological dispositions, we might naturalistically attend to different information in the world around us, thereby experiencing different realities even when exposed to the same environments. In particular, we suggest that relative to individuals more tolerant of group-based hierarchy, social egalitarians—ideologically committed to the goal of reducing the gap between socially disadvantaged and advantaged groups—are vigilant for and perceptually “ready” to notice inequality when it is present (33–35). Indeed, relative to individuals more tolerant of hierarchy, those who strongly believe in the need to make the world more equal might be more likely to chronically encode the world in inequality-relevant terms. Consider two people sitting in a workplace meeting in which the men in the room happen to disproportionately dominate the conversation. An individual committed to group-based equality might, naturalistically, be more likely to vigilantly encode the proportion of airtime dominated by men as compared to women. By contrast, an individual dispositionally more tolerant of inequality might not think to encode the conversation through the lens of gender-based speaking time share. These two individuals might then arrive at meaningfully different conclusions about the existence of inequality in speaking time. Of note, this process does not require any downstream motivated rationalization by those who oppose or tolerate inequality. Rather, it reflects differences arising early in the cognitive stream as a function of the differential motivational relevance of evidence about inequality—that is, the degree to which evidence of inequality is seen as worth attending to (36).

Our theorizing builds on research about the effects of motivation on selective attention outside the domain of ideological beliefs (37, 38). Hungry individuals, relative to those low in hunger, show a greater attentional bias for food-related stimuli (39), and addicts give preferential attention to the object of addiction relative to control stimuli (40). Preferential attention to motivationally relevant stimuli occurs in social contexts too. Individuals for whom the threat of social exclusion was made experimentally salient were faster than control participants to identify smiling faces within a crowd (41). Low socioeconomic status (SES) individuals, who prioritize interdependence with others, are more likely than high SES individuals (who prioritize independence) to naturalistically attend to faces of other people in their environment (42). And work on goal-directed cognition has shown that individuals asked to write about instances in which they treated members of disadvantaged groups (e.g., obese people, homosexuals) unfairly (versus fairly) generated a goal to compensate that led them to pay more attention to goal-relevant (but task irrelevant) words like “justice” and “fairness” on a reaction time task (35, 43).

Here, we investigated across five studies (including 10 samples and five distinct paradigms; total N = 8,779) whether chronic differences in ideological beliefs about the desirability of group-based equality would shape individuals’ attention to and accuracy in detecting inequality. Study 1 examined naturalistic attention to cues of inequality in urban scenes. Study 2 examined basic social cognition using a go/no go task analyzed using a signal detection framework to assess whether spontaneous attention to inequality manifested in greater accuracy at detecting inequality in resource distribution. Study 3 used a speeded change detection task to naturalistically index individuals’ visual attention to inequality-relevant aspects of social scenes. Because inequality is more motivationally relevant to them, we predicted in our first three studies that individuals strongly committed to social equality would be more attentive to and more accurate at detecting evidence of inequality than individuals more tolerant of inequality. In Studies 4 and 5, we moved beyond inequality impacting only socially disadvantaged groups and manipulated the social standing of inequality’s victims, allowing us to consider two competing predictions regarding the link between egalitarianism and attention to inequality. On the one hand, to the extent that inequality per se is motivationally relevant for social egalitarians, they should attend to evidence of inequality irrespective of whether the group receiving unequal treatment is socially advantaged or disadvantaged. On the other hand, recent research suggests that social egalitarians are primarily motivated by closing the gap between groups in society, thereby treating targets differently as a function of these targets’ societal group status [e.g., preferentially empathizing with and amplifying successes of disadvantaged over advantaged group members (44–46)]. From this perspective, it is specifically inequality that harms socially disadvantaged groups that is motivationally relevant for social egalitarians, and thus, any link between social egalitarianism and heightened attention to inequality might apply selectively to instances in which the inequality harms groups at the bottom of society.

Study 1

The primary aim of Study 1 was to examine how an individual’s (anti-)egalitarianism (assessed by their SDO) predicts their spontaneous tendency to notice inequality in everyday urban scenes. We examined this across five samples of participants (total n = 2,204) who viewed a series of 6 to 10 photographs of urban scenes, half of which contained cues relevant to economic inequality. For each image, we simply asked participants to report what they noticed, without making any mention of inequality.

We developed a coding scheme to analyze participants’ open-ended responses that could isolate “direct” from “indirect” mentions of inequality, the former involving an explicit mention of inequality in the scene and the latter involving the citing of cues concerning both low- and high-status targets in an image (e.g., a luxury car, a homeless person; see Fig. 1 for examples of inequality-relevant and neutral images). Although we were centrally interested in attention to inequality per se, exploratory analyses also considered the extent to which participants reported (“1”) or failed to report (“0”) high-status and low-status cues separately (SI Appendix, section 2.7).

Fig. 1.

Examples of images used in Study 1. (Top) Examples of inequality-relevant images. (Top Left) A luxury car (high-status cue) and a homeless man with a shopping cart (low-status cue). (Top Right) A businesswoman in the center (high-status cue) and homeless people in the foreground (low-status cue). (Bottom) Examples of neutral images.

We conducted a meta-analysis across all five samples to examine the correlations between SDO and mentions of inequality (see SI Appendix, section 2.8 for forest plots). SDO was significantly negatively correlated with Direct Inequality, fixed effects model: z = −2.89, P = 0.004, r = −0.06, random effects model: z = −2.19, P = 0.03, r = −0.07. In addition, SDO was significantly negatively correlated with Indirect Inequality, fixed effects model: z = −3.44, P < 0.001, r = −0.07, random effects model: z = −2.93, P = 0.003, r = −0.08. That is, whether through reporting it as a salient issue or picking up on inequality-relevant details in a scene, those low (versus high) in anti-egalitarianism were more likely to notice inequality in images of contemporary urban life—images similar to those they might encounter in their own everyday lives. This is a demonstration of ideological differences in spontaneous attention to inequality, going further than previous work that has focused on the interpretation of information about inequality when inequality is explicitly identified as a dimension of interest.

Study 2

The findings of Study 1 suggest that an ideological commitment to reducing social inequality facilitates spontaneous attention to inequality in everyday urban scenes. Still, it is possible that individuals who are more tolerant of hierarchy are just as likely to notice inequality cues but simply less likely to report noticing them. On the other hand, if, as we argue, ideological beliefs shape the extent to which one is chronically cognitively attuned to inequality-related stimuli, then this should be reflected in greater accuracy at detecting inequality in a rapid-response cognitive task. Study 2 (n = 1,406) assessed this possibility using the signal detection paradigm.

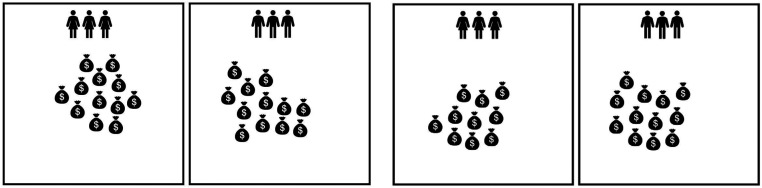

We employed a go/no go task that asked participants to judge, across 120 trials, whether two distributions of a socially relevant resource were equal or unequal to one another. On any given trial, participants saw the same picture of a group of men and a group of women (separated by a divider), each with a set of money bags associated with them. On “equal’ trials, the distribution of money bags associated with men and women was equal (Fig. 2, Left). On “unequal” trials, the group of men had more money bags than the group of women did (in this experiment, inequality therefore was always at the expense of the socially disadvantaged group) (Fig. 2, Right).

Fig. 2.

Sample stimuli from Study 2. (Left) A sample image of an “equal” trial. (Right) A sample image of an “unequal” trial. Across stimuli, and for both equal and unequal trials, we varied the total number of money bags that appeared and how they were visually arrayed.

On “go” trials, participants were told to hit the space bar. On “no go” trials, participants were asked to refrain from hitting any key on the keyboard. Trials advanced after 6 s or (if sooner) when participants hit the space bar. We counterbalanced whether participants were instructed to hit the space bar (“go” trials) when the two distributions of money bags were equal or unequal. We used the signal detection framework to calculate our key dependent variables: sensitivity (d’) and response bias (c). Sensitivity (d’) in this case indexes an individual’s ability to accurately differentiate between equal and unequal trials. Larger d’ values indicate more accuracy at distinguishing equal from unequal trials. In practical terms, having a larger d’ value means an individual was more likely to correctly notice inequality when it was present and the absence of inequality when it was absent. Response bias (c) indexes participants’ bias toward responding in a particular direction (i.e., a bias toward stating that the distributions are equal or unequal). A c value of 0 indicates no bias in responding. We coded c values such that positive values always indicate a bias toward responding that the two images are equal and negative values always indicate a bias toward responding that the two images are unequal. In practical terms, having a negative c value means an individual is inclined to see inequality even in its absence, and an individual who has a positive c value sees equality even in its absence.

As predicted, we found that SDO was significantly negatively correlated with d’, r = −0.08, P = 0.002, suggesting that individuals lower (versus higher) in SDO were more accurate at the task. In contrast, the relationship between c and SDO was not significant, r = −0.01, P = 0.76.

Thus, using a speeded task assessing basic social cognition, social egalitarians—individuals chronically motivated to reduce the gap between groups at the top and bottom of society—were more accurate than anti-egalitarians at arbitrating whether inequality was present or absent, consistent with the possibility that they were more attentionally vigilant for it. We did not find any evidence suggesting that social egalitarians have a bias toward claiming inequality. That is, egalitarians’ response pattern was marked by more accurately arbitrating whether inequality was present or absent rather than simply a lower threshold for claiming inequality (even in its absence).

Study 3

The goal of Studies 3a and 3b was to combine the strengths of Study 1 in terms of its focus on naturalistic attention to inequality cues and the strengths of Study 2 in terms of its focus on the processing of inequality-related information early in the cognitive stream. Both Studies 3a and 3b relied on a speeded task indexing attention and omitted any reference to inequality during the task, which we did to provide a direct index of spontaneous attention to inequality.

Participants completed 10 trials of a flicker task (47) in which they were presented with a set of two images, shown sequentially and repeatedly, and asked to indicate the first point at which they noticed the detail that differed between the two images. In inequality trials, the change involved a detail relevant to signs of economic inequality (e.g., a homeless man’s bag disappearing; see Fig. 3). In neutral trials, the change was irrelevant to social inequality (e.g., a message disappearing from a bus LED screen) (see SI Appendix, section 4.1 for all images). Once participants hit the space bar to indicate they noticed the change, they were asked to describe in detail what changed in the image.

Fig. 3.

An example of an inequality-relevant original image and changed image with the change identified.

We were primarily interested in how many views of the flickering sequence passed before participants (correctly) noticed changes occurring in inequality-relevant images. This number served as a proxy for their attention to different parts of the image (those paying closer attention at baseline to parts of the scene in which the change occurs should be faster to notice the change). We also controlled for how long it took participants to (correctly) notice changes occurring in the neutral images, which served as a proxy for the ability of participants to detect general changes in images. If participants identified the change correctly (as rated by manual coders), we reported their score as the number of views after which they hit the space bar (e.g., 11, if they hit the space bar after 11 views of the sequence). If participants reported the change incorrectly, we set their time at the maximum of 25 views irrespective of when they hit the space bar (as preregistered). We averaged participants’ number of views for each of the inequality-relevant and neutral sets of images.

Using our preregistered analysis plan for Study 3a (n = 1,027), we found our expected positive correlation between SDO and the average number of views for inequality images (r = 0.15, P < 0.001), which held even when controlling for the average number of views for neutral images (b = 0.08, t (1,024) = 3.07, P = 0.002; here and throughout, we used ordinary least squares regression unless otherwise specified). This suggests that individuals lower in SDO were more attentive to inequality (i.e., they needed less time to identify the inequality-relevant change) and that this could not be accounted for controlling for more general attentiveness on the task (i.e., performance on neutral trials).

Despite this supportive evidence, we decided to replicate Study 3a in Study 3b (n = 1,474) with a conservative adjustment in preregistered exclusion criteria. Specifically, we excluded participants with low rates of overall accuracy in identifying the changes in images (i.e., those without at least three out of five trials correct in each of the inequality-relevant and neutral categories). We also included the number of views only for trials on which participants were accurate and improved upon the set of neutral images (see Methods for more details and SI Appendix, section 4.2 for rationale).

We averaged participants’ number of views (on correct trials) for each of the inequality-relevant and neutral sets of images. We observed that SDO was significantly positively correlated with the average number of views on inequality trials, r = 0.10, P < 0.001. When controlling for the average number of views on neutral trials, SDO was a marginally significant predictor of the average number of views on inequality trials, b = 0.04, t (1,471) = 1.89, P = 0.059. These relationships were robust when meta-analyzing across Studies 3a and 3b (zero-order r = 0.13, z = 6.35, P < 0.001; controlling for neutral trials, b = 0.06, z = 2.82, P = 0.005), including when analyzing both studies using Study 3b’s updated exclusion criteria (zero-order r = 0.11, z = 5.52, P < 0.001; controlling for neutral trials, b = 0.05, z = 2.32, P = 0.02).

Thus, across two substudies without any prompting regarding the theme of inequality, we obtained evidence suggesting that individuals more committed to social egalitarianism are chronically more visually attentive to cues of inequality in everyday urban scenes.

Study 4

One notable aspect of Study 3 was that all of the inequality-relevant changes involved low-status targets (e.g., homeless people). This raises the possibility that egalitarians are particularly attuned to inequality only when it involves bias against groups that they ideologically favor (i.e., socially disadvantaged groups). This would also be consistent with the findings of Study 2, in which the disadvantaged group in the go/no go task, women, is also a disadvantaged group in society.

We thus turned in Study 4 (n = 1,467) to examine, using a financially incentivized task, how the link between an individual’s (anti-)egalitarianism and their attention to and accuracy in detecting inequality might depend on the target of that inequality. Specifically, we examined how the relationship between (anti-)egalitarianism and accuracy in detecting inequalities in the distribution of talking time between men and women on a panel differed depending on whether it was men (a socially advantaged group) or women (a socially disadvantaged group) who took up a disproportionate share of the talking time.

All participants watched a 4 min and 30 s video depicting a discussion panel consisting of two men and two women. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (edited from the same source material): 1) a condition in which the men spoke 1.5× longer than the women or 2) a condition in which the women spoke 1.5× longer than the men. Prior to watching the video, participants were incentivized to pay close attention to the video as they would be answering a series of memory questions afterward with the individuals responding most accurately receiving a $50 prize (participants were not told what aspects of the video we were interested in, and inequality was never mentioned). By providing a financial incentive for all to focus on the task, we reduce the possibility that any link between SDO and accuracy/attention to inequality is affected by higher SDO individuals simply responding more carelessly to experiments in general (and/or experiments that appear to them to investigate inequality).

Our key dependent measures were all generated from a question that asked participants to “Please select the chart that you think best represents the ratio of speaking time for men and women.” Participants were randomly presented with seven pie charts to choose from, depicting the following speaking-time ratios: 1) 35% men/65% women, 2) 40% men/60% women, 3) 45% men/55% women, 4) 50% men/50% women, 5) 55% men/45% women, 6) 60% men/40% women, and 7) 65% men/35% women (SI Appendix, Fig. S31). In condition one, the correct answer was 60% men/40% women. In condition two, the correct answer was 40% men/60% women.

We dichotomously examined whether or not participants selected the correct answer: participants received a score of “1” if they selected the correct pie chart for their condition and a score of “0” otherwise. We also dichotomously coded whether participants made a selection indicating (separately) underestimation and overestimation of the inequality actually faced by the disfavored target in their bias condition (a score of “0” indicated the absence of underestimation or overestimation; a score of “1” indicated that participants’ selection was an underestimate or overestimate, depending on the measure). We also report in SI Appendix, section 5.6 (consistent) results examining degree of underestimation (note that we could not assess continuous levels of overestimation because—for reasons we explain in SI Appendix, section 5.5—there was only one pie chart choice reflecting overestimation).

Given that our dependent variables in this study were dichotomous, we used binomial logistic regression throughout. We observed a marginally significant interaction effect, b = 0.19, P = 0.08, 90% [0.01, 0.36], between SDO and task condition in predicting accurate pie chart selection (SI Appendix, Fig. S32). In the condition where men spoke more than women, we observed a negative main effect of SDO on accuracy, b = −0.19, P = 0.01, odds ratio (OR) = 0.83, 95% [0.70, 0.96], with egalitarians significantly more likely to select the accurate pie chart than those higher on anti-egalitarianism. In contrast, in the condition where women spoke more than men, there were no significant differences between individuals lower and higher in SDO in terms of accuracy, b = −0.01, P = 0.92, OR = 0.99, 95% [0.86, 1.14]. At low levels of SDO (−1 SD below the mean; MSDO = 2.58, SD = 1.29), task condition was not a significant predictor of accuracy; individuals lower in SDO were equally likely to select the correct speaking-time pie chart in condition one (where men spoke more) versus condition two (where women spoke more), b = −0.05, P = 0.80, OR = 0.95, 95% [0.66, 1.36]. At high levels of SDO (+1 SD above the mean), however, individuals were significantly more likely to select the correct pie chart in condition two (where women spoke more) relative to condition one (where men spoke more), b = 0.43, P = 0.03, OR = 1.54, 95% [1.04, 2.29].

Turning to our measure of underestimation, we observed a significant interaction effect, b = −0.20, P = 0.01, 95% [−0.37, −0.04], between SDO and bias condition (Fig. 4). In the condition where men spoke more than women, individuals lower (versus higher) in SDO were significantly less likely to underestimate the level of inequality, b = 0.16, P = 0.01, OR = 1.17, 95% [1.04, 1.31]. In contrast, when women spoke more than men, SDO did not significantly predict underestimation, b = −0.05, P = 0.40, OR = 0.95, 95% [0.85, 1.06]. Examining the interaction another way, individuals lower in SDO (−1 SD) were more likely to underestimate inequality when women spoke more than when men spoke more, b = 0.76, P < 0.001, OR = 2.14, 95% [1.60, 2.89]. Individuals higher in SDO (+1 SD), by contrast, were no more likely to underestimate inequality in one condition versus the other, b = 0.24, P = 0.11, OR = 1.27, 95% [0.95, 1.70].

Fig. 4.

Predicted probability of participants underestimating inequality in pie chart selection by condition in Study 4. A score of “0” corresponds to an accurate or overestimating selection, and “1” corresponds to underestimating inequality. Note that data points on this graph are “jittered” via R to aid in visualization (values of this variable are only “0” or “1”).

Finally, we observed no significant interaction effect between SDO and bias condition on overestimation, b = 0.11, P = 0.19, 95% [−0.06, 0.29] (SI Appendix, Fig. S33). When men spoke more than women, we observed no significant association between SDO and the likelihood of overestimating inequality, b = −0.05, P = 0.44, OR = 0.95, 95% [0.85, 1.07]. The same was true when women spoke more than men, b = 0.07, P = 0.29, OR = 1.07, 95% [0.94, 1.22]. For those both lower and higher in SDO (−/+1 SD), there was a significant main effect of task condition, such that individuals were less likely to overestimate the level of inequality when women spoke more than men relative to when men spoke more than women (at −1 SD: b = −0.84, P < 0.001, OR = 0.43, 95% [0.31, 0.59]; at +1 SD: b = −0.55, P < 0.001, OR = 0.58, 95% [0.42, 0.79]).

Across the three measures, then, when women were disadvantaged, social egalitarians (versus those more tolerant of social hierarchy) had 1) a significantly more accurate score on our measure of accuracy, 2) were significantly less likely to underestimate inequality, and 3) were no more likely to overestimate inequality. These accuracy advantages for social egalitarians tended to dissipate (but not reverse) when men were disadvantaged.

Study 5

In Study 5 (n = 1,201), we again examined how an individual’s (anti-)egalitarianism differentially predicts their attention to unequal treatment depending on the social standing of the target of that inequality, this time in the domain of racial biases in hiring. Specifically, we examined how (anti-)egalitarianism predicted attention to racial bias in hiring across two experimental conditions: 1) a condition in which there was anti-minority bias in hiring and 2) a condition in which there was (equivalent) anti-White bias in hiring. In addition, we went further than previous studies by considering downstream consequences, examining whether individuals who noticed inequality were more likely than those who did not notice it to want to investigate the hiring process.

Participants read about an organization called Connection Consulting that had just completed their hiring process and were shown the resumes of 56 applicants who varied across five dimensions (grade point average [GPA], major, race, hometown, and hobby; SI Appendix, Fig. S37). Half of the applicants were White, and half of the applicants were racial minorities (Latino, Asian, Black). After viewing each candidate’s resume, participants learned whether that applicant was hired or not. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, which differed only in terms of the correlation between race and likelihood of being hired: in condition one, being a minority (versus White) was correlated at r = −0.29 with the likelihood of being hired, whereas in condition two, being a minority (versus White) was correlated at r = +0.29 with the likelihood of being hired. In both conditions, the task was structured such that GPA was correlated at r = +0.57 with the likelihood of being hired and the correlation between all other factors (major, hometown, hobby) and being hired was 0.

We assessed the extent to which participants noticed inequality across the two conditions by asking participants, after they completed the resume task, to “Please note anything that stood out to you about the hiring process.” We then coded for whether participants naturalistically mentioned inequality in the hiring process. For this metric, which we termed naturalistic notice bias, we dichotomously coded whether or not participants—correctly—mentioned unequal treatment against the group actually disadvantaged within their experimental condition. Participants in condition one received a score of “1” if they mentioned inequality against minorities and a score of “0” otherwise. Participants in condition two received a score of “1” if they mentioned inequality against Whites and a “0” otherwise. Note that we also assessed attention to inequality using three other metrics, including by directly asking participants about their perceptions of bias against both Whites and minorities on self-report scales (analyses yielded comparable conclusions; SI Appendix, sections 6.4–6.6).

We also assessed a downstream consequence of noticing inequality, namely, the extent to which participants endorsed investigating Connection Consulting for its hiring practices, termed desire to investigate (five-item scale; sample item: “A third party should investigate Connection Consulting’s hiring practices”; α = 0.94).

Using binomial logistic regression, we observed a significant interaction effect, b = 0.44, P < 0.001, 95% [0.26, 0.62], between SDO and bias direction condition in predicting whether participants naturalistically (and correctly) noticed bias. In the anti-minority bias condition, we observed our predicted main effect of SDO, b = −0.36, P < 0.001, OR = 0.70, 95% [0.61, 0.79]: in line with the conclusions of Studies 1 to 4, individuals lower (versus higher) in SDO were significantly more likely to notice bias against racial minorities when it was present. In contrast, in the anti-White bias condition, we observed a positive but nonsignificant trend between SDO and naturalistically mentioning racial bias (b = 0.08, P = 0.22, OR = 1.08, 95% [0.95, 1.23], see Fig. 5, Top; of note, this positive association between SDO and perceived bias against Whites was significant using self-reported measures of perceived bias, see SI Appendix, section 6.5). At low levels of SDO (−1 SD below the mean—MSDO = 2.77, SD = 1.43), bias direction condition was a significant predictor of naturalistically noticing bias; individuals lower in SDO were significantly more likely to naturalistically mention bias in condition one (anti-minority bias condition) versus condition two (anti-White bias condition), b = −1.25, P < 0.001, OR = 0.29, 95% [0.20, 0.41]. At high levels of SDO (+1 SD above the mean), there was no significant difference between the likelihood of naturalistically noticing bias across the two conditions, b = 0.001, P = 1.00, OR = 1.00, 95% [0.69, 1.44]. Individuals even higher in SDO (+2 SD above the mean) were significantly more likely to naturalistically mention bias in the anti-White bias versus anti-minority bias condition, b = 0.65, P = 0.03, OR = 1.92, 95% [1.06, 3.46]. Of note, it was low SDOs in the condition where there was bias against minorities who exhibited the highest overall likelihood of (correctly) noting bias (about 50.6%).

Fig. 5.

The link between SDO and each of naturalistically noticing bias (Top) and desire to investigate “Connection Consulting” (Bottom) as a function of experimental condition (whether bias was against minorities or against Whites). Note that data points on both panels of the figure are “jittered” via R to aid in visualization.

We also observed a significant interaction between SDO and task condition in predicting the desire to investigate Connection Consulting, b = 0.50, P < 0.001, 95% [0.37, 0.63]. In the anti-minority bias condition, individuals higher (versus lower) in SDO reported significantly less desire to investigate, b = −0.27, P < 0.001, 95% [−0.36, −0.18], whereas when there was anti-White bias, we found that individuals higher (versus lower) in SDO reported a significantly greater desire to investigate, b = 0.23, P < 0.001, 95% [0.13, 0.32] (Fig. 5, Bottom). Individuals lower in SDO (−1 SD below mean) reported a significantly greater desire to investigate in the anti-minority versus anti-White bias condition, b = −1.15, P < 0.001, 95% [−1.41, −0.89], whereas individuals higher in SDO (+1 SD above mean) reported a marginally greater desire to investigate in the anti-White versus anti-minority bias condition, b = 0.25, P = 0.055, 95% [−0.01, 0.51].

We next examined evidence for moderated mediation. We entered SDO as the predictor, naturalistic notice bias as the mediator, and desire to investigate as the outcome measure, with bias condition as a moderator of each of the a, b, and c paths (SI Appendix, Fig. S41). In the anti-minority bias condition, there was a significant negative indirect effect of SDO on desire to investigate via naturalistically (and correctly) noticing the bias, b = −0.12, SE = 0.02, 95% [−0.16, −0.08]. In contrast, in the anti-White bias condition, there was no significant indirect effect of SDO on desire to investigate via naturalistic notice bias, b = 0.02, SE = 0.02, 95% [−0.02, 0.06]. For individuals lower in SDO (−1 SD below mean), the indirect effect of task condition on desire to investigate via naturalistically noticing bias was significantly negative, b = −0.44, SE = 0.07, 95% [−0.58, −0.30]. For individuals higher in SDO (+1 SD above mean), the indirect effect of task condition on desire to investigate via naturalistically noticing bias was not significant, b = −0.002, SE = 0.05, 95% [−0.09, 0.09]. Of note, results using self-reported bias in place of naturalistic notice bias replicated these moderated mediation results and further revealed a significantly positive indirect effect in the anti-White bias condition and among high SDOs (SI Appendix, section 6.6).

Discussion

Inequality between groups is one of the predominant issues of our time, and yet, individuals often disagree across ideological lines about its extent, its victims, and what, if anything, to do about it. Prior research suggests that, when confronted with evidence of or specifically asked about inequality, individuals engage in motivated reasoning, interpreting information in ways that align with their propensity to favor or oppose egalitarian social intervention. However, being explicitly asked to evaluate inequality is the least representative of the ways we might encounter it in the world. As we go about our daily lives engaging in mundane activities, from everyday commutes through urban areas to attending conferences or participating in recruitment efforts in our organizations, we regularly encounter cues of group-based inequality: discrepancies between rich and poor, gender-based differences in recognition and airtime, and race-based discrimination in who gets hired. Who notices these cues, and when? Extending research showing how ideological preferences shape how we rationalize inequality-related information, our work shows how they also affect the likelihood that we attend to such information in the first place. Supplemental analyses further suggest that these differences are specific to our ideological beliefs and cannot simply be accounted for by our racial, gender, or class group memberships (SI Appendix, section 7). Considering differences in basic attention to inequality can thus shed new light on the growing ideological polarization characteristic of contemporary policy debates.

We reasoned that because inequality is chronically motivationally relevant to those who strongly oppose group-based hierarchy, these social egalitarians would be more likely to scan for and notice inequality than those more tolerant of group-based hierarchy. Consistent with our reasoning, in Study 1, those lower (versus higher) in anti-egalitarianism (as indexed by SDO) were more likely to naturalistically mention inequality when we simply showed them a variety of everyday social scenes, some of which contained inequality-relevant cues. In Study 2, using a very basic speeded cognitive task, egalitarians were also better at accurately differentiating distributions of resources which favored men over women from equal distributions. Combining naturalistic scenes with a visual attention paradigm, Study 3 found that social egalitarians (versus anti-egalitarians) were faster to detect inequality-relevant changes to visual scenes, suggesting a heightened attentional focus to any evidence of inequality.

Inequality in Studies 1 to 3 always adversely impacted societally disadvantaged groups (e.g., women, the poor, minorities). Thus, these three studies raised a key theoretical question—do social egalitarians chronically attend to all types of inequality, or do they notice some inequalities more than others? To test this, in addition to introducing new forms of inequality, Studies 4 to 5 varied the social standing of the group impacted by inequality. Leveraging social contexts in which inequality has been hotly debated, we experimentally manipulated whether participants encountered panels in which men versus women dominated speaking time (Study 4) or hiring processes in which White versus minority candidates were disadvantaged (Study 5). We replicated our findings of ideological bias in inequality attention in these novel contexts, again observing that social egalitarians (versus anti-egalitarians) were significantly more likely to naturalistically (and accurately) notice inequality when it was traditionally disadvantaged groups on the receiving end. Critically, however, egalitarians were not more likely (and were sometimes less likely) than anti-egalitarians to notice when inequality negatively impacted traditionally advantaged groups. These differences were consequential, occurring despite the fact that participants were financially incentivized to engage with the task and honestly report their perceptions (Study 4) and predicting downstream desires to investigate a company’s hiring practices (Study 5).

Practically, our findings shed light on why we might so often come to disagree about the state of the world. Social egalitarians and the wider political left might be bewildered and frustrated when others fail to notice or encode (and thereby seem to downplay) the mistreatment that traditionally disadvantaged groups so often experience (and for which egalitarians remain vigilant). As a function of their own perceptual tendencies, on the other hand, individuals more tolerant of inequality between groups (typically on the political right) might come to feel that egalitarians are seeing inequality where none exists or come to feel aggrieved at what they might consider a hypocritical tendency to selectively attend to some types of inequality but not others.

Theoretically, our findings not only contribute evidence supporting an attentional mechanism by which motivations can influence inequality perception (36) but also extend a range of recent work suggesting that (anti-)egalitarians’ perceptions and behavior are deeply impacted by the social standing of those they encounter. For example, whereas work historically suggested that egalitarians are dispositionally more empathic than anti-egalitarians, recent research illustrates that egalitarians express more empathy toward the suffering of socially disadvantaged targets but less for that of advantaged targets (44). Similarly, in contrast to those on the political right, those on the political left preferentially amplify the successes of women and racial minorities (e.g., by tweeting about them) over those of men and Whites (45), a differentiation that is statistically mediated by their desire to help bring about intergroup equality. This work suggests that social egalitarians are primarily invested in closing the gap between groups at the bottom and those at the top, which might require a selective focus on improving the lot of traditionally disadvantaged groups (despite any seeming contradictions implied by preferential treatment in service of group-based equality). Our finding here that social egalitarians are more attentive to evidence of inequality faced by socially disadvantaged versus advantaged groups is highly consistent with this emerging proposition.

At the same time, it is important to note that our results do not support any notion that egalitarians saw inequality that did not exist. In Study 2, we found a significant link between egalitarianism and higher d’ scores (accuracy at differentiating equality from inequality) but no relationship between egalitarianism and c (the tendency to claim inequality independent of accuracy). Moreover, in Study 4, social egalitarians were a) more accurate and b) less likely to underestimate speaking-time inequality disadvantaging women but not more likely to overestimate inequality affecting women. It is also worth noting that the interactions by target status we observed in Studies 4 and 5 tended not to be “full cross-over” interactions—that is, the egalitarian “advantage” in noticing inequality impacting low-status groups often appeared larger than anti-egalitarians’ comparable advantage in noticing inequality impacting high-status groups. Indeed, the single highest score for accurately noticing bias in Study 5 was among egalitarians encountering inequality disadvantaging low-status groups (Fig. 5), as was the single lowest score for underestimating inequality in Study 4 (Fig. 4). And notably, when men spoke more (Study 4) or Whites were advantaged (Study 5), egalitarians were no less likely to notice than anti-egalitarians. In sum, egalitarians appear to be especially apt to notice inequality affecting those at the bottom where it exists as opposed to seeing inequality where none exists or being especially likely to overlook inequality affecting those at the top.

Despite the contributions of our work, there are several limitations worth noting. For one, the effect sizes we observed were, despite their robustness, typically small. Although this is unsurprising given that we were typically dealing with difficult speeded cognitive tasks and obscuring from participants our interest in inequality, we cannot readily conclude from our findings that there are overwhelming differences in how individuals lower and higher in (anti-)egalitarianism attend to their social environments. Still, our effect sizes are consistent with other similar research (42, 48), and because we were investigating naturalistic attention to inequality of the type that individuals are likely to encounter on a very regular basis, even small differences can add up. We attempted here to test our theorizing across a broad range of experimental paradigms. Still, in examining our effects further, it would be valuable to further diversify the paradigms we employed and to move beyond laboratory-based methods to further consider attention to inequality “in the wild.”’ For example, it would be worth considering daily diary methods in which individuals are asked at random intervals of the day to report on interactions or events that stood out to them (49) and code for whether individuals are differentially likely to mention inequality-relevant topics as a function of their ideological leanings. It would also be interesting to use eye-tracking goggles to examine what individuals visually attend to during their daily commutes. It would be especially valuable to explore whether these types of differences in attention to inequality outside the laboratory shape support for real-world social policies as our analysis of the desire to investigate “Connection Consulting” preliminarily suggests. Beyond different methods, it is also important to test our patterns in different social and cultural contexts—although our work has the advantage of considering inequality across a number of distinct domains (class, gender, race), most of our work was conducted with US participants, and it remains to be seen whether we would obtain the same results in non-WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, Democratic) (50) contexts or in contexts where the topic of inequality is less politicized.

It is also worth noting that whereas Studies 1–4 focused largely on attention to unequal outcomes, Study 5 considered attention to evidence of unequal treatment in a hiring process (a process that itself shapes unequal outcomes in terms of access to jobs, an important material resource). We think it is likely that egalitarianism is associated with attention to unequal outcomes and unequal processes that negatively impact disadvantaged groups for similar reasons, namely because inequality affecting socially disadvantaged groups is more motivationally relevant for egalitarians. To give an example, we think the person who is more likely to notice if men receive more graduate school acceptances than women is also more likely to notice—and for the same reasons—if a faculty member reviewing applications is more likely to remark favorably on the merits of male applicants than equally qualified female applicants. Still, it would be good for future research to consider whether there might be differences between attention to inequality in process versus outcome.

Finally, future work could consider ways in which we might be able to nudge individuals to pay more attention to (or become more accurate at detecting) inequality. In the current work, we generally attempted to limit participants’ awareness of our interest in inequality because we were specifically interested in spontaneous attention to inequality. However, if we instead directly nudged people to try to encode inequality in the world around them, might we be able to durably reduce the types of bias blind spots that society regularly laments—such as those in hiring, representation, and inclusiveness—and to do so in a way that brings people across the ideological divide onto the same page?

Conclusion

Although inequality is one of the most pressing issues of our time, we often disagree about the scope of the problem, the identity of its victims, and the appropriate actions to take. We highlight the role that ideological motives play in this process by—selectively—shaping our attention to inequality in the world around us.

Methods

Studies 2 to 5 were preregistered (see SI Appendix, section 1 for preregistration links and information regarding a solitary deviation in Study 4). Additional details of sample demographics and sensitivity or power analyses for all studies are available in SI Appendix. All studies were approved by Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Study 1 was approved under IRB number STU00206116, Study 2 was approved under IRB number STU00201913, Studies 3 and 5 were approved under IRB number STU00208924, and Study 4 was approved under IRB number STU00211028. All participants provided informed consent.

Study 1.

Sample 1a consisted of 227 participants from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) of whom 200 provided data on all focal variables. Sample 1b consisted of 527 participants from MTurk of whom 507 provided data on all focal variables. Sample 1c was collected using Prolific Academic and included 522 participants residing in the United Kingdom of whom 519 provided data on all focal variables. Sample 1d consisted of 738 participants from MTurk of whom 607 provided data on all focal variables.

Across samples 1a to 1d, participants were asked to complete a visual attention task. Participants were shown a series of images and for each image were given the following instructions: “What stands out to you in this image? Please list three things that stand out to you.” The task instructions were altered slightly for Studies 1b and 1c. Participants in these studies saw the following instructions: “From the image above, please list the first three concrete details (e.g., objects, characters, clothing) that you notice.”

We used a variety of focal and distractor images across each study, sampling across a broad range of stimuli (SI Appendix, section 2.4). The focal images each depicted inequality-relevant scenes. Specifically, these images juxtaposed, in the same visual scene, certain cues reflecting high status (e.g., wealthy women receiving pedicures, luxury vehicles) and low status (e.g., employees at a nail salon, a homeless person’s cart). The distractor images were scenes without any obvious inequality-relevant content.

Across samples 1a to 1d, we coded participant responses (i.e., what they wrote stood out to them about each image) to the inequality-relevant images according to a coding scheme which captured both explicit mentions of the principle of inequality as well as a pattern of observations that indirectly indicated attention to inequality. We coded a response as “1” for Direct Inequality if the response explicitly mentioned status differences in the image or remarked explicitly on the fact that the scene depicted inequality. To assess Indirect Inequality, we coded for whether participants mentioned both high- and low-status cues associated with each of the inequality-relevant images (see SI Appendix, section 2.5 for detailed coding scheme information). Across samples, one rater coded the entire dataset for both direct and indirect attention to inequality. To assess coding reliability, a second rater coded a subset of half of the responses for each image (all κs > 0.70). In samples 1a, 1c, and 1d, we assessed (anti-)egalitarianism using the 16-item SDO7 scale (αs > 0.85); in sample 1b, we used the 8-item SDO7(s) (18) (α = 0.92).

For sample 1e, we conducted our study in two waves, 1 wk apart, beginning with a sample of 571 participants using MTurk. A total of 368 participants (64.4%) returned to complete the second wave (see SI Appendix, section 2.6 for attrition analyses). In wave one, participants filled out the 16-item SDO7 measure (α = 0.95). In wave two, participants completed the same visual attention task. Here, though, we experimentally manipulated the task instructions, with half of participants receiving General Impression task instructions (“What is your impression of the image? Please write at least three sentences.”) and the other half receiving Concrete Details task instructions (“Please list three features of the image that stand out to you”). We reasoned that the relationship between (anti-)egalitarianism and attention to inequality might be more apparent with the Direct Inequality outcome measure in the General Impression instructions condition but more pronounced with the Indirect Inequality outcome measure in the Concrete Details condition (see SI Appendix, section 2.7 for relevant analyses). Participant responses were coded using the coding scheme described above.

Study 2.

In total, we collected data from 1,591 participants using MTurk of whom 1,544 provided data on all focal variables. As preregistered, and based on a relevant simulation (SI Appendix, section 3.4), we excluded participants who had over 17 consecutive “go” responses or “no go” responses. We chose this threshold as an indicator of inattentive responding which could, if correlated with SDO, artificially inflate associations between SDO and accuracy (conclusions were equivalent without this exclusion; see SI Appendix, section 3.4). Excluding 185 participants who surpassed this threshold left us with a final sample of 1,406 participants for analyses (88.4% of the original sample).

To assess participants’ sensitivity to inequality, we developed a go/no go task. We presented participants across a series of trials with images composed of two arrays of objects that were either equal or unequal and asked them to judge—at speed (to prevent counting)—whether the arrays were equal or unequal. We created 120 stimuli pairs (60 equal, 60 unequal), each depicting two arrays of money bags. In each pair, one array of money bags was presented beneath three icons of men, and the other was presented beneath three icons of women. For each stimulus pair, the number of money bags depicted below the men was either 1) equal to the number of money bags shown below the women or 2) greater than the number of money bags shown below the women, consistent with societal differences in gender equality. We varied the number and spatial distribution of money bags across pairs (SI Appendix, section 3.3). We counterbalanced the task instructions participants received. In one version of the task, participants were asked to hit the space bar when the two distributions of money bags were unequal (“go” trials) and to refrain from hitting any key on the keyboard when the two distributions of money bags were equal (“no go” trials). In the other version, the instructions were reversed. Trials advanced after 6 s, or if sooner, when participants hit the space bar.

We assessed (anti-)egalitarianism using the 16-item SDO7 scale (18). Responses were provided on a 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”) scale (α = 0.95).

Study 3a.

We collected data from 1,027 participants using MTurk, split about evenly between Republicans and Democrats (to ensure a wide range of SDO scores). Because we preregistered no exclusions, this number represented our final sample.

Participants completed 10 trials of a flicker task (47), including five inequality-relevant and five neutral trials presented in a random order. Participants viewed an original image for 1 s followed by a blank screen for 250 ms. This was followed by a changed version of the original image for 350 ms followed by a second blank screen for 250 ms. This sequence repeated until participants hit the space bar to indicate they noticed the change, upon which they were asked to describe in detail what changed in the image. In inequality trials, the change involved an inequality-relevant cue (e.g., a homeless man’s bag disappearing). In neutral trials, the change was irrelevant to social inequality (e.g., a message disappearing from a bus LED screen). We pretested the stimuli sets, ensuring that the changes differed significantly on perceived inequality relevance (SI Appendix, section 4.1).

The flickering sequence repeated at maximum 25 times before moving to the next trial, during which time participants were asked to hit the space bar once they noticed the change. At that point (or after the 25 maximum repetitions were up), participants were asked to describe the change in detail. If participants identified the change correctly (as rated by manual coders), we reported their score for that trial as the number of views at which they hit the space bar (e.g., 11, if they hit the space bar after 11 views of the sequence). As preregistered, if participants reported the change incorrectly, we automatically set their time for that trial at the maximum of 25 views.

We assessed (anti-)egalitarianism using the 16-item SDO7 scale (α = 0.95).

Study 3b.

We collected data from 1,514 participants using MTurk, split about evenly between Republicans and Democrats. The task procedure for Study 3b was identical to that of Study 3a except we replaced two neutral images that had relatively higher rates of inaccurate responding and updated our preregistered analytic criteria (SI Appendix, section 4.2). We pretested all images in Study 3b to ensure that over 90% of participants correctly noticed the change for each image. As preregistered (and in contrast to Study 3a), if participants reported the change incorrectly, we ignored their time for that image. As preregistered, we excluded participants who received more than four “incorrect” responses across all 10 trials or more than two “incorrect” responses across either of the neutral or inequality-relevant trials (ensuring that for each participant there were, at minimum, times from three “correct” trials entering into both the inequality and neutral composites). With exclusions applied, our sample was 1,474 participants (97.4% of full sample).

We assessed (anti-)egalitarianism using the 16-item SDO7 scale (α = 0.94).

Study 4.

We conducted this study with a sample of 2,130 participants using MTurk, split about evenly between Democrats and Republicans. Of these, 1,467 provided data on all focal variables after the exclusions reported below (approximating our intended sample size of 1,600 after exclusions; see SI Appendix, section 5.2).

All participants watched a video lasting 4 min and 30 s depicting a panel of two men and two women discussing designing technology for users (see SI Appendix, section 5.4 for links to the videos). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions 1) a condition in which the men spoke 1.5× longer than the women or 2) a condition in which the women spoke 1.5× longer than the men. Within each condition, we counterbalanced the version of the video participants watched. Participants watched one of two versions of the same panel in which we varied which gender spoke first and which gender spoke last (to vary which gender might have been more salient due to primacy or recency effects). Prior to watching the video, participants were informed that, after the video, they would be answering a series of memory questions and that the individuals who respond most accurately to those questions would receive a $50 prize. After watching the video, participants were asked to “describe, to the best of your ability, what the video was about.” As preregistered, we began by excluding participants (n = 175) we determined as clearly not indicating knowledge of what was in the video (based on ratings from blind coders to an open-ended question asking participants to summarize the video’s contents). In addition, we excluded participants who missed an attention check embedded in our survey (n = 19 additional participants) and participants who our software indicated did not complete the survey in the default full screen mode (n = 469 additional participants), leaving us with a final sample of 1,467 participants.

We assessed (anti-)egalitarianism using the 16-item SDO7 scale (α = 0.94).

Study 5.

We conducted this study with a sample of 1,603 participants using MTurk, split about evenly between Republicans and Democrats. As preregistered, we included only the 1,394 participants (86.9%) who passed an attention check of whom 1,201 provided data on all focal variables.

Participants read about an organization called Connection Consulting that had just completed their hiring process. Participants saw the resumes of 56 applicants who varied across five dimensions (GPA, major, race, hometown, and hobby). Half of the applicants were White, and half of the applicants were racial minorities (Latino, Asian, Black). The applicants were presented in proportions consistent with racial group representation in the US Census. After viewing each candidate’s resume, participants learned whether that applicant was hired or not (see SI Appendix, Fig. S37 for sample stimuli). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In both conditions, the task was structured such that GPA was correlated at +0.57 with the likelihood of being hired. Candidates’ GPAs ranged from 3.4 to 4.0 in 0.1 increments. Candidates were assigned to one of seven majors (assigned in equal numbers to Whites and minorities and in equal numbers across each GPA category). In addition, candidates were assigned to one of 28 hometowns and one of 28 hobbies (each appearing once for White candidates and once for minority candidates). Across both conditions, we structured the task such that the correlation between other factors (major, hometown, hobby) and the likelihood of being hired was 0. The only difference between the two conditions was the correlation between race and likelihood of being hired: in condition one (anti-minority bias), being a minority (versus White) was correlated at −0.29 with the likelihood of being hired, whereas in condition two (anti-White bias), being a minority (versus White) was correlated at +0.29 with the likelihood of being hired.

We assessed (anti-)egalitarianism using the 16-item SDO7 scale (α = 0.95).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2023985118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Anonymized comma-separated values data files and R syntax have been deposited in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/a4zbp/).

References

- 1.Graf N., Brown A., Patten E., The narrowing, but persistent, gender gap in pay. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/03/22/gender-pay-gap-facts/. Accessed 16 September 2020.

- 2.Hegewisch A., Lacarte V., Gender inequality, work hours, and the future of work. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/employment-and-earnings/gender-inequality-work-hours-and-the-future-of-work/. Accessed 16 September 2020.

- 3.Obermeyer Z., Powers B., Vogeli C., Mullainathan S., Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 366, 447–453 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voigt R., et al., Language from police body camera footage shows racial disparities in officer respect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6521–6526 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvaredo F., Chancel L., Piketty T., Saez E., Zucman G., “Trends in global income inequality” in World Inequality Report 2018, Alvaredo F., Chancel L., Piketty T., Saez E., Zucman G., Eds. (Belknap Press, 2018), pp. 38–93. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbash F., The war on ‘microaggressions:’ Has it created a ‘victimhood culture’ on campuses? Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/10/28/the-war-over-words-literally-on-some-american-campuses-where-asking-where-are-you-from-is-a-microaggression/. Accessed 16 September 2020.

- 7.Kunda Z., The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 108, 480–498 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumeister R. F., “The self” in The Handbook of Social Psychology, Gilbert D. T., Fiske S. T., Lindzey G., Eds. (McGraw-Hill, 1998), pp. 680–740. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sedikides C., Rudich E. A., Gregg A. P., Kumashiro M., Rusbult C., Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: Self-esteem matters. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 400–416 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunning D., Perie M., Story A. L., Self-serving prototypes of social categories. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 957–968 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ditto P. H., Lopez D. F., Motivated skepticism: Use of differential decision criteria for preferred and nonpreferred conclusions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 568–584 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waytz A., Young L. L., Ginges J., Motive attribution asymmetry for love vs. hate drives intractable conflict. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 15687–15692 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eibach R. P., Ehrlinger J., “Keep your eyes on the prize”: Reference points and racial differences in assessing progress toward equality. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 66–77 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taber C. S., Lodge M., Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 50, 755–769 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lord C. G., Ross L., Lepper M. R., Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 37, 2098–2109 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennes E. P., Ruisch B. C., Feygina I., Monteiro C. A., Jost J. T., Motivated recall in the service of the economic system: The case of anthropogenic climate change. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145, 755–771 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahan D. M., Hoffman D. A., Braman D., Evans D., Rachlinski J. J., “They saw a protest”: Cognitive illiberalism and the speech-conduct distinction. Stanford Law Rev. 64, 851–906 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho A. K., et al., The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO7 scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 109, 1003–1028 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jost J. T., Glaser J., Kruglanski A. W., Sulloway F. J., Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bull. 129, 339–375 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham J., Haidt J., Nosek B. A., Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 1029–1046 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford J. T., Jussim L., Cain T. R., Cohen F., Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation differentially predict biased evaluations of media reports. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 43, 163–174 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unzueta M. M., Knowles E. D., Ho G. C., Diversity is what you want it to be: How social-dominance motives affect construals of diversity. Psychol. Sci. 23, 303–309 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eibach R. P., Keegan T., Free at last? Social dominance, loss aversion, and White and Black Americans’ differing assessments of racial progress. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 453–467 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norton M. I., Ariely D., Building a better America–One wealth quintile at a time. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 9–12 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraus M. W., Rucker J. M., Richeson J. A., Americans misperceive racial economic equality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 10324–10331 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chambers J. R., Swan L. K., Heesacker M., Better off than we know: Distorted perceptions of incomes and income inequality in America. Psychol. Sci. 25, 613–618 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chambers J. R., Swan L. K., Heesacker M., Perceptions of U.S. social mobility are divided (and distorted) along ideological lines. Psychol. Sci. 26, 413–423 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidai S., Gilovich T., Building a more mobile America–Oone income quintile at a time. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 60–71 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidai S., Gilovich T., How should we think about Americans’ beliefs about economic mobility? Judgm. Decis. Mak. 13, 297–304 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahn K., Ho A. K., Sidanius J., Pratto F., The space between us and them: Perceptions of status differences. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 12, 591–604 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawtry R. J., Sutton R. M., Sibley C. G., Why wealthier people think people are wealthier, and why it matters: From social sampling to attitudes to redistribution. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1389–1400 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kteily N. S., Sheehy-Skeffington J., Ho A. K., Hierarchy in the eye of the beholder: (Anti-)egalitarianism shapes perceived levels of social inequality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 112, 136–159 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bargh J. A., Pratto F., Individual construct accessibility and perceptual selection. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 22, 293–311 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruner J. S., On perceptual readiness. Psychol. Rev. 64, 123–152 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moskowitz G. B., Li P., Ignarri C., Stone J., Compensatory cognition associated with egalitarian goals. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 365–370 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips L. T., et al., Inequality in people’s minds. psyarxiv [Preprint] 2020. https://psyarxiv.com/vawh9/ (Accessed 26 September 2020).

- 37.Ro T., Russell C., Lavie N., Changing faces: A detection advantage in the flicker paradigm. Psychol. Sci. 12, 94–99 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Summerfield C., Egner T., Expectation (and attention) in visual cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13, 403–409 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mogg K., Bradley B. P., Hyare H., Lee S., Selective attention to food-related stimuli in hunger: Are attentional biases specific to emotional and psychopathological states, or are they also found in normal drive states? Behav. Res. Ther. 36, 227–237 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hogarth L. C., Mogg K., Bradley B. P., Duka T., Dickinson A., Attentional orienting towards smoking-related stimuli. Behav. Pharmacol. 14, 153–160 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dewall C. N., Maner J. K., Rouby D. A., Social exclusion and early-stage interpersonal perception: Selective attention to signs of acceptance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 729–741 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dietze P., Knowles E. D., Social class and the motivational relevance of other human beings: Evidence from visual attention. Psychol. Sci. 27, 1517–1527 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moskowitz G. B., Preconscious effects of temporary goals on attention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 397–404 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucas B. J., Kteily N. S., (Anti-)egalitarianism differentially predicts empathy for members of advantaged versus disadvantaged groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 114, 665–692 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kteily N. S., Rocklage M. D., McClanahan K., Ho A. K., Political ideology shapes the amplification of the accomplishments of disadvantaged vs. advantaged group members. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 1559–1568 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Badaan V., Jost J. T., Conceptual, empirical, and practical problems with the claim that intolerance, prejudice, and discrimination are equivalent on the political left and right. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 34, 229–238 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rensink R. A., O’Regan J. K., Clark J. J., To see or not to see: The need for attention to perceive changes in scenes. Psychol. Sci. 8, 368–373 (1997). [Google Scholar]