Significance

Popular wisdom suggests that the internet plays a major role in influencing people’s attitudes and behaviors related to politics, such as by providing slanted sources of information. Yet evidence for this proposition is elusive due to methodological difficulties and the multifaceted nature of online media effects. This study breaks ground by demonstrating a nudge-like approach for exploring these effects through a combination of real-world experimentation and computational social science techniques. The results confirm that it is difficult for people to be persuaded by competing media accounts during a contentious election campaign. At the same time, data from a longer time span suggest that the real consequence of online partisan media may be an erosion of trust in mainstream news.

Keywords: media, politics, polarization, computational social science

Abstract

What role do ideologically extreme media play in the polarization of society? Here we report results from a randomized longitudinal field experiment embedded in a nationally representative online panel survey ( = 1,037) in which participants were incentivized to change their browser default settings and social media following patterns, boosting the likelihood of encountering news with either a left-leaning (HuffPost) or right-leaning (Fox News) slant during the 2018 US midterm election campaign. Data on 19 million web visits by respondents indicate that resulting changes in news consumption persisted for at least 8 wk. Greater exposure to partisan news can cause immediate but short-lived increases in website visits and knowledge of recent events. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, however, we find little evidence of a direct impact on opinions or affect. Still, results from later survey waves suggest that both treatments produce a lasting and meaningful decrease in trust in the mainstream media up to 1 y later. Consistent with the minimal-effects tradition, direct consequences of online partisan media are limited, although our findings raise questions about the possibility of subtle, cumulative dynamics. The combination of experimentation and computational social science techniques illustrates a powerful approach for studying the long-term consequences of exposure to partisan news.

The internet is transforming society. One of the fundamental ways in which this is occurring is by dramatically increasing the availability of information. In removing barriers to access, some have debated whether the internet is a democratizing force that helps to level the playing field for underrepresented perspectives and social movements (1, 2). These dynamics have eroded the power of traditional gatekeepers to set the boundaries of debate, allowing a wider range of perspectives—but also rumors, misinformation, and biased accounts of reality—to flourish (3–5). These structural changes to the information environment have profound implications for understanding the ways people seek political information and their political behaviors. Scholars have debated the extent to which online news consumers exhibit a preference for politically congenial sources (6–8). This evidence on people’s information consumption raises questions about its causal impact, especially among those frequently exposed to partisan sources of news.

Assessing the consequences of slanted news requires overcoming well-known challenges in the study of media effects. Previous studies have sought to address bias due to self-selection of news sources (9), the artificiality of forced-stimuli designs (10–12), and the unreliability of traditional measures of media exposure (13, 14). Experimental research designs have focused on the relatively short-term impact of curated treatments such as individual news articles or TV clips in controlled settings. For these reasons, consensus on the impact of media in a fragmented, polarized social media age remains elusive (15).

As a result, there is a large gap between academic discussions of these issues and popular accounts about the internet’s role in fostering divisions in society. This state of affairs echoes decades of research in the minimal effects tradition, which argues that media primarily reinforce existing predispositions (16). At the same time, more recent research strongly implies that newspapers and especially cable news can change people’s voting behavior, especially those without strong partisan attachments (17–20). We propose an internet-age synthesis that views people’s information environments through the lens of choice architecture (21): frictions, subtle design features, and default settings that structure people’s online experience. In this view, small changes (or nudges) could disproportionately affect information consumption habits that have downstream consequences.

To that end, we designed a large, longitudinal online field experiment that subtly but naturalistically increased people’s exposure to partisan news websites. Our choice of treatment is ecologically valid: Despite the importance of social media for agenda-setting (22) and public expression (23), more Americans continue to say that they get news from news websites or apps than social media sites (24). The intervention thus served as a nudge, boosting the likelihood that subjects encountered news framed with a partisan slant during their day-to-day web browsing experience, even if inadvertently. The powerful, sustained nature of the intervention and our ability to track participants with survey and behavioral data for months provided the opportunity to test a range of hypotheses about the long-term impact of online partisan media.

Our preregistered hypotheses were divided into two separate studies for analysis. Study 1 covers a range of outcomes assessing how partisan media affects political polarization. Study 2 focuses mainly on information and credibility—how our partisan media treatments affect media trust, political knowledge, and the accuracy of election predictions. The first set of hypotheses in study 1 relates to the effects of partisan media exposure on people’s attitudes and opinions. Research on persuasion and opinion change suggests that individuals take cues from the media—especially those that highlight copartisan elite figures—when evaluating candidates and policy options (25, 26). We follow recent research in looking for shifts in policy opinions across a range of issues (27). In addition, we test for effects on a range of outcomes based on findings in prior research, including agenda-setting (9), which has been powerfully demonstrated in one of the few longitudinal field experiments on social media (23); affective polarization (28); and perceived polarization (29). For these and other outcomes, a minimal-effects interpretation of the evidence to date would lead to an expectation of negligible impact. At the same time, recent formulations of this tradition argue that salient issues may be an exception (ref. 15, p. 725). For this reason, we additionally preregistered a hypothesis about attitudes toward immigration, which was the topic of contentious debate during the 2018 US midterm election campaign, during which this study was fielded.

Second, we test hypotheses related to online and offline political behavior. A potential immediate consequence of increased exposure to partisan political coverage is changes to one’s information diet, including possible lasting effects on media consumption habits. This expectation is consistent with viewing our intervention as a subtle nudge altering informational default options (21). Expanding beyond online media, it is possible that exposure to information could motivate people to behave differently on social media, either directly—by sharing links to viewed articles and posts—or indirectly, by altering the amount of posting activity (3).

Third, we study the effect of partisan media on trust in the media generally (study 2). The long-term decline in trust and confidence in the mainstream press has been linked to numerous potential causes, most plausibly an increase in attacks from political elites and elected officials (30). Since this behavior is not symmetric across political parties in the United States, patterns of media trust have become polarized (31). The rise of blogs and social media has further enabled critiques of mainstream coverage; consistent with this, tendencies toward partisan selective exposure are related to a belief that the media is biased (32). Perceptions of bias have a rich history in studies of exposure to media content (33–35). The well-known hostile media phenomenon was demonstrated in scenarios modeled on the broadcast era, with ostensibly neutral or balanced stimuli. Related dynamics have also been shown in response to partisan news shows (36). In both sets of studies, however, outcomes focus on subjects’ attitudes toward the specific clips, shows, or hosts shown as treatments rather than the media writ large. Building on evidence of partisan criticism of the media overall and the effects of partisan media on trust toward specific sources or figures, it is reasonable to ask whether partisan media can reduce the general public’s overall level of trust in the mainstream press. This has not been the focus of prior experimental research in the United States. Finally, we assess the basic ability of media to enhance people’s recall of current news events (37), a key question for understanding whether people are receptive to information from partisan media outlets, even ones they may not trust.

Design.

To test these hypotheses, we worked with an online polling firm to field a nationally representative panel survey of Americans, which interviewed the same respondents eight times from July 2018 to October 2019 (Fig. 1). These respondents were recruited from YouGov’s Pulse panel, which unobtrusively collects anonymous web visit and mobile app use data from those who consent to install passive metering software. To maintain realism within the high-choice online environment of our subjects, we opted for an encouragement design (38). In the third wave of the survey, we randomly incentivized subsets of our sample to change the default homepage on their primary web browsers for one month. One-third of the sample was asked to set their homepage to Fox News (foxnews.com) and one-third to HuffPost (huffingtonpost.com), while the last third was assigned to a pure control group. The treatment encouragement was aimed at browsers on desktop computers or laptops. We additionally asked subjects in each treatment group to follow the source’s associated Facebook page and subscribe to affiliated newsletters in order to maximize the strength of the intervention (39). We collected pretreatment survey measures in the first three waves of the panel and posttreatment outcomes beginning in wave 4. The size of our final experimental sample ( = 1,037), a rich set of pretreatment covariates, and repeated measures of our dependent variables allow for reasonably well-powered estimates: as we detail in SI Appendix, the minimum detectable intent-to-treat (ITT) effect for most survey outcomes is small (). The web data collected from our panelists, comprising more than 19 million visits over a 2-mo period, allows us to create both pretreatment and posttreatment measures of news consumption as well as to measure treatment compliance more precisely than previous research. In addition to web visits, our digital trace data include Twitter posts and follow lists from respondents who agreed to share their usernames for research purposes. This design builds off of previous research demonstrating the potential for field experiments to answer questions about media and political behavior (18) by studying higher-frequency exposure to partisan news content and covering a range of outcomes beyond those typically associated with research on news impact.

Fig. 1.

Overview of study design. Subjects in wave 3 who were randomly assigned to the Fox News or HuffPost encouragement groups were offered $8 in YouGov incentives to participate in the treatment.

Results.

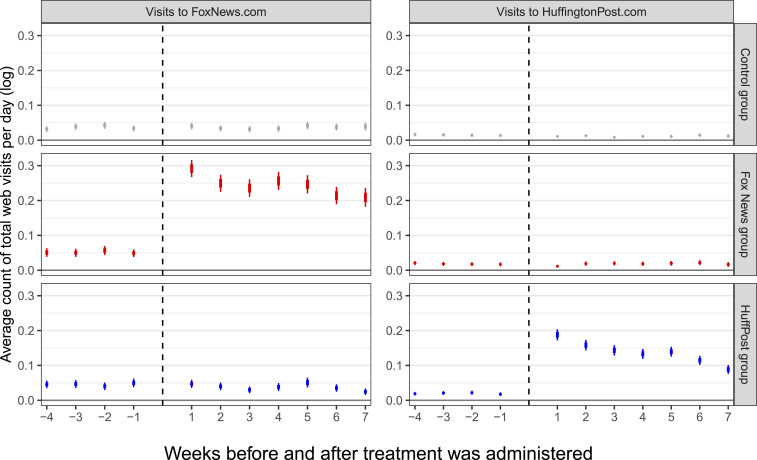

We characterize the first stage of our treatments to verify that they increased real-world exposure to online partisan media as intended (Fig. 2). In the first 7 d postencouragement, our web tracking data reveal that subjects assigned to the HuffPost treatment visited approximately one additional page on the site per day (; ) compared to the control group, and those assigned to the Fox News treatment visited between three and four additional pages on that site per day on average (; ). Neither treatment detectably increased visits to the other site. Focusing on time spent on pages from each site reveals that the intensity of the corresponding treatments in the first week was significant: a mean increase of nearly 50 s per day on the HuffPost site (; ) and more than 2 min per day on the Fox News site (; ). By comparison, participants in the pretreatment period spent less than 34 min per week on news-related websites. The impact of treatment is still measurable in the eighth week, with an estimated average of 0.34 additional visits to HuffPost and 3.66 additional visits to Fox News per day due to the intervention (). These results suggest that the Fox News treatment was inherently more powerful, although reassuringly, the estimated share of compliers for each treatment is similar according to a preregistered measure—approximately 29% among those for whom we have digital trace data.* The compliers of our study—participants agreeing to share web visit data who consumed Fox News or HuffPost if and only if encouraged to do so—tend to score higher on political interest than the rest of the sample. Reassuringly, there are no strong differences in ideology or pretreatment visits to Fox News or HuffPost either between compliers and the rest of the sample or between compliers of the two treatments. This indicates that our treatments did not merely increase exposure to partisan news among those who already consume it. We explore the characteristics of compliers in more detail in SI Appendix, section 2.2.

Fig. 2.

Weekly average log(number of visits + 1) to (Left) foxnews.com and (Right) huffingtonpost.com by treatment assignment, with 68% (thick lines) and 95% (thin lines) confidence intervals. Behavioral data are from YouGov Pulse panelists.

Looking beyond averages, we find reassuring evidence that a substantial proportion of our sample was induced to visit Fox News or HuffPost: 57% of those in the Fox News treatment group increased their visits to Fox News compared to baseline, and 50% of the HuffPost group increased their visits to HuffPost. We also show in SI Appendix, section 2.2, that the treatments induced new visits to the partisan websites among a quarter to a third of those who had not visited them at all prior to the experiment and that about a third of each treatment group increased consumption of their assigned websites by a factor of at least 10.

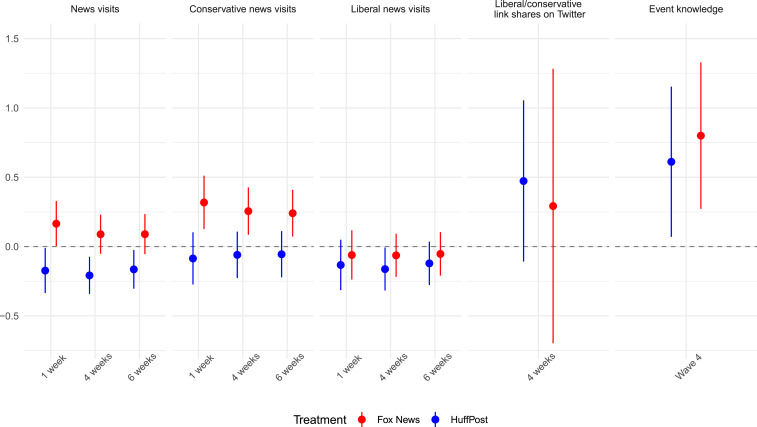

The exogenous increase in partisan news exposure induced by the randomized encouragement led to additional changes in subjects’ news diets in the weeks after the intervention. Although we could not detect an increase in visits to liberal news sites other than HuffPost as a result of that treatment, Fox News boosted visits to other conservative news sites in the first week (; ), an effect that barely decayed after the sixth week (Fig. 3). A possible explanation for the divergent partisan effects on news consumption is that HuffPost effectively acted as a substitute for other news sources, while Fox, given its centrality in conservative media, drove traffic to other sites in the ecosystem (40). Regardless of the difference, both treatments immediately increased subjects’ ability to recognize recent events in the news and to distinguish them from made-up events (Fig. 3, Right). This finding is notable given popular accounts that Fox News, in particular, causes people to become less informed (41, 42).

Fig. 3.

Summary of effects (with 95% confidence intervals) on news visits/shares (study 1) and event knowledge (study 2). For visits, coefficients represent effect of treatment assignment on over given time period postintervention. Each visit type (hard news, conservative news, and liberal news) excludes visits to both foxnews.com and huffingtonpost.com. Shares data show containing liberal (HuffPost treatment) or conservative (Fox News treatment) links. Models are fully saturated OLS regressions with indicator variables for browser using preregistered LASSO covariate selection procedure. For event knowledge, standardized coefficients represent CACE estimates from two-stage least squares models in which treatment receipt, measured using web visit data, is instrumented with treatment assignment.

Turning to less proximate outcomes, we uncover results that in many ways provide support for a minimalist view of media impact. Especially after correcting for multiple comparisons within studies (SI Appendix, section 7), we do not find measurable impact on many attitudes and behaviors (Fig. 4). We are able to rule out modest effects (Cohen’s ) of either treatment on agenda-setting, elite approval, and an index of issue positions. We also cannot reject the null hypothesis that exposure to either treatment shifted people’s feelings toward the parties or that they affected perceptions of polarization, self-reported vote turnout intentions, or social media activity (following news sources and sharing links on Twitter), although these effects are less precisely estimated.† Results remain similar even after we tested revised hypotheses by directly comparing the two treatment groups with each other (SI Appendix, section 6). These findings are consistent with recent research evaluating the persuasive impact of advertising and campaign contact, which suggest negligible effects especially in settings that map onto the political divide (43, 44). They also align with a recent field experiment on the effects of Facebook news subscriptions (39), which similarly finds no changes in opinions (however, the study does find that counterattitudinal news reduces negative attitudes toward the out-party).

Fig. 4.

Summary of effects (with 95% confidence intervals) on issue importance, attitudes, and self-reported behavior. Standardized coefficients represent CACE estimates from two-stage least squares models in which treatment receipt, measured using web visit data, is instrumented with treatment assignment and covariates are selected via LASSO.

At the same time, we uncover findings that suggest an underappreciated pathway of influence. First, we produce evidence that Fox News online caused among our subjects a decrease in overall trust and confidence in the mainstream media within the first several weeks of boosted exposure (complier average causal effect [CACE], SD; ), although this does not survive any of our multiple comparisons adjustments (corrected, ). However, looking beyond our original panel data to waves that we subsequently collected, we find a lasting effect not only for Fox News (CACE, SD; ) but for HuffPost as well (CACE, SD; ) approximately 5 mo after the intervention (in wave 7), with little decay. Remarkably, these changes appear fairly durable even after a year (in wave 8) with similar magnitudes, although the effect of Fox News (CACE, SD; ) falls short of significance at the 95% level (two-sided) in contrast to HuffPost (CACE, SD; ). Substantively, the size of these effects is large, equivalent to 40% of the difference between liberals’ and conservatives’ average levels of media trust in the sample (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Although we did not specifically preregister analyses beyond wave 5, we interpret these additional results—along with a continuing lack of significant effects on our other survey measures on these later waves—as indicative of a subtle, long-term media effect that has eluded the attention of prior research.

Discussion

In this article, we demonstrate a methodological framework for studying the effect of social media and the internet on individuals. By embedding a naturalistic encouragement in an online panel survey with linked digital trace data, our design achieves ecological validity without sacrificing internal validity (45). This approach does not come without costs: our intervention was necessarily a bundle, although multiple survey waves allowed us to prespecify and test for different pathways of influence. While our sample enables fairly precise estimates of main effects, we are generally not well powered to test for subgroup effects (see SI Appendix for analyses of heterogeneous effects by party, ideology, and pretreatment media consumption).

The longitudinal nature of our data enables us to study the cumulative effects of a relatively strong intervention: increased real-world exposure to either a left-leaning or right-leaning partisan news source. Encouraging people to alter their online information environments in this way seems to work on a basic level: it can increase awareness of recent political events. However, for most of the kinds of outcomes frequently studied by social scientists—such as voting behavior, agenda-setting, and affective polarization—we do not find strong evidence of direct influence. Despite the seismic technological, societal, and political shifts of the past 75 y, this evidence is consistent with a tradition of research on media’s minimal effects arising out of the Second World War (16).

In assessing the generalizability of our findings, we consider how the experimental participants who complied with the treatment differ from the population. In a best-case scenario for strong effects, we could have had compliers who are infrequent news consumers, highly inattentive, and with weak political preferences, or in the other extreme, compliers could have been partisan, frequent consumers of political news with more crystallized attitudes. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S12, the compliers in this study are comparable to the overall sample in many important respects, including pretreatment visits to Fox News/HuffPost, ideology, and age, although they are notably more interested in politics (more than 80% of compliers have very high political interest compared to an already-high 70% in the full sample).‡Thus, while our treatments did not simply increase the partisan news consumption of people who already visit such websites, they did successfully encourage people who tended to have a higher interest in politics to begin with. For this reason, it may be reasonable to think of our findings on attitudes and behavior as closer to the lower bound of possible effects as compared to research focusing on compliers with a different, less politically engaged profile (20). Further, our study was conducted during the Trump presidency, when a polarized and high-volume political media environment plausibly pretreated these engaged citizens, potentially attenuating the effects of our randomized encouragements (46). Understanding the limited effects of exposure to partisan media on relatively engaged partisans is itself of substantive interest, given the outsize visibility and political influence of this group (8). At the same time, it is precisely people with these characteristics—interested in politics but not frequent partisan news consumers—who may have less crystallized views about the media in general.

Our suggestive results on the long-term consequences of increased exposure to online partisan news for overall trust in the media point to a possible resolution of a related puzzle in research on consumption of online news and its effects: controlled experiments have often found that exposure to partisan media content causes polarization, although whether this is driven by the inadvertent audience (11) or already polarized partisans (27, 47) remains the subject of debate. At the same time, fine-grained evidence on people’s online news diets reveals that the actual consumption of partisan content is limited and that exposure to cross-cutting information is relatively common on the web and on social media (3, 8, 48, 49). If echo chambers are not as common as popular discourse suggests, then can online partisan media be to blame for polarization (50)? Our findings on lowered overall trust in mainstream media suggest an answer: even if people are regularly exposed to content (partisan or not) that challenges them, they may more heavily discount it as their trust and confidence in news decreases. In this way, partisan media can help drive polarization—although not necessarily by influencing opinions directly, as the null effects on our index of issue positions indicates. This conclusion has mixed normative implications: it may be more difficult than ever for people to be swayed by potentially inflammatory partisan content encountered on the internet, but this may come at the cost of reduced trust in crucial informational intermediaries that work to sustain agreement on a shared set of facts and norms. This is an important topic for continued research.

In a direct test of the power of defaults to structure the information environment, our primary nudge urged participants to set their browser homepages—an option they may not have been aware existed (51). As illustrated by our tracking data, this simple change had lasting impact on downstream web consumption, suggesting that a behavioral science perspective can usefully be applied to people’s interactions with internet media (52). The intervention can be interpreted as boosting incidental exposure to partisan content in a way that might be comparable to seeing posts from weak ties on social media (e.g., retweets or reshares) that are more likely to be political and counterattitudinal in nature. Taken together, our findings point to the conclusion that despite today’s extremely high-choice media environment (53), frictions and “architectures of serendipity” (50) can still, at least in principle, allow for engagement with different perspectives in the news.

Materials and Methods

Sampling and Participants.

In partnership with the online survey firm YouGov, we initially recruited a total of 1,551 respondents from the Pulse panel, a subset of YouGov’s traditional survey panels in which members opt in to install passive metering software on their desktop and mobile devices.

Respondents agreed to join a “Politics and Media” study with multiple survey waves. Their participation was rewarded using YouGov’s proprietary points system and included a bonus for completing all waves in order to disincentivize attrition. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were able to opt out from the passive metering part of the study at any time. Respondents were sampled according to YouGov’s demographic/political targets and then reweighted in order to obtain a sample that is representative of the US population (54).

Specifically, respondents were weighted to a sampling frame constructed from the full 2016 American Community Survey 1-y sample. The sample cases were weighted to the sampling frame using propensity scores. The weights were then poststratified on 2016 presidential vote choice and a four-way stratification of gender, age (four categories), race (four categories), and education (four categories) to produce the final weights.

Digital Trace Data.

The Pulse panel uses passive metering technology developed by Reality Mine which relies on a combination of proxy connections and browser plug-ins to collect real-time data on web visits and mobile app use. After preprocessing, we are left with 19,105,773 URL visits (laptop/desktop and mobile/tablet combined) covering the period September 1 to October 28, 2018. Respondents provided informed consent and were given the ability to pause or halt data sharing at any time; see below for details on consent and privacy protections and refs. 5, 8 for extensive validation. We also scraped homepages and article text from Fox News and HuffPost stories published in 2018.

News visits were identified based on the list of top 500 domains shared on Facebook and compiled in ref. 3. We classify domains as liberal or conservative based on their audience ideology score (negative for liberal and positive for conservative), which was computed by ref. 3 based on the self-reported political identity of Facebook users that shared those URLs on Facebook.

In addition to web data, we collected public Twitter data linked to respondents who agreed to share their profile information with the researchers via an approved authentication app. In addition to survey respondents’ posted tweets, we periodically collected the friends (followees) and followers of participants’ Twitter accounts during the study period.

Survey Waves and Treatment.

Fig. 1 provides an overview of the data collection process. We conducted multiple survey waves: a baseline survey (wave 1, July 3 to 22, 2018; ), a survey with additional pretreatment covariates (wave 2, August 28 to September 10, 2018; ), another survey with pretreatment covariates in which the treatments were administered (wave 3, October 5 to 29, 2018; ), and a posttreatment survey that contained our outcome measures and was fielded immediately prior to the midterm elections (wave 4, October 30 to November 5, 2018; ). An additional wave was designed to test for persistence of effects (wave 5, December 20, 2018, to January 7, 2019; ), and three more waves (not part of our preanalysis plan) were fielded through October 2019.

In the first two waves of the survey, we asked a battery of questions about news media consumption, attitudes about domestic and foreign policy issues, turnout and vote choice, and presidential approval (wave 1) as well as affective polarization, social distance, news reception, policy attitudes, and projected US midterm election outcomes (wave 2). Question wordings and response options for all survey items in all waves used in the study are available in SI Appendix.

The treatment was deployed in wave 3 starting on October 5, 2018. For the experiment, we administered a randomized encouragement: one third of the sample was asked to change their browser homepage to a left-leaning news outlet (huffingtonpost.com), another third was asked to change it to a right-leaning news outlet (foxnews.com), and another third received no encouragement (control group).§ The encouragement also asked respondents to follow the sites’ corresponding Facebook pages and sign up for related email newsletters. Selection of these news sites was not only based on the significance of Fox News and HuffPost in the current political environment but also based on empirical web-tracking data during the pretreatment period.

Randomization was blocked by detected pretreatment browser type (Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Internet Explorer, Edge, and a sixth category for others). Respondents received clear, tailored instructions for how to follow the encouragement and were compensated for doing so with a YouGov points reward equivalent of $8 (in addition to standard incentives for completing the surveys). Wave 3 also included a few questions related to other pretreatment covariates: attitudes about domestic and foreign issues, most important problem, presidential feeling thermometer, Congress control preference after the midterms, and turnout intention.

Wave 4 was in the field from October 30 to November 5 (the day before the election). This wave was longer than wave 3 and included a battery of outcome variables, such as attitudes about domestic and foreign issues, most important problem, political knowledge, political perceptions, affective polarization, presidential approval and vote intention/choice, racial resentment, threat perceptions, beliefs about the effects of trade, social media use, and media trust (including trust specifically in HuffPost and Fox News). For our primary analyses, we subset the sample to only those respondents who took part in waves 3 and 4. This reduces our sample size to . Additional details about the surveys, including all question wordings and attrition, are available in SI Appendix.

Analysis.

We estimate average treatment effects using both weighted difference-in-means and saturated regressions (55). Both methods enable unbiased estimation of treatment effects given our blocked randomization procedure. For all regressions, we use a LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) procedure to select covariates.

To estimate the treatment effect among compliers, or the CACE, we also use an instrumental-variables framework (56). This requires a credible measure of treatment take-up, which we construct using web visit data in the week after subjects receive the encouragement. In SI Appendix we specify our definition and coding rules for this variable, which we preregistered given the many possible ways in which compliance could potentially be measured.

Consent and Ethics.

Collecting passive behavioral data that can be linked to survey responses poses privacy and ethical challenges beyond those typically associated with traditional social science research methods (57). We join other researchers in striving to meet these challenges with robust procedures designed to ensure that informed consent is obtained, privacy is protected, and personally identifiable information is not stored or reported. For the data analyzed in this study, we followed a strict protocol informed by Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidance and emerging best practices (58). This study was approved by the IRBs of Princeton University (protocols 8327, 10014, and 10041) and the University of Southern California (UP-17-00513) and authorized by the University of Illinois via a designated IRB agreement.

First, as with any survey research, respondents are anonymous to the researchers. While we do not ask for identifying information, it is possible that some subjects visited websites or made search queries that contain personal details (for example, by visiting one’s own Facebook profile page). While we did not collect the content of these pages, the URLs themselves could contain such information.¶ We handle this by keeping the raw web visit data stored securely in a strictly separate location from the survey data and by performing the primary analyses for the paper using only individual-level variables that are aggregated to the respondent level (as with counts or shares of visits). Only these aggregates are being released as replication data.

Second, sharing web visits with researchers is done with fully informed consent. People who join the Pulse panel are told about the nature of the data collected, that it is kept anonymous, and that data are not shared with third parties. They are also told that the software can be removed at any time or paused temporarily. When subjects join the Pulse panel, they are given a clear privacy policy that says, in part, that they agree to collection of information about their internet behavior and sociodemographic characteristics. Before joining this specific study, respondents additionally agreed to a separate consent statement informing them, “Your participation is voluntary. Participation involves completion of a short survey and voluntary tracking of online media consumption. You may choose not to answer any or all questions. Furthermore, you are free to opt out of web tracking, which you may have previously agreed to participate in as part of the YouGov Pulse panel, at any time.”

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was generously funded by a grant from the Volkswagen Foundation Computational Social Science Initiative, reference 92 143. The experiment was additionally supported by the Princeton University Committee on Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences and the Center for International Studies at the University of Southern California. We thank Jona Ronen and Will Schulz for excellent research assistance. We thank workshop attendees at Rutgers University, the Hertie School, University of Frankfurt, University of Konstanz, Leiden University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab, University of California, Los Angeles, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Stanford University; participants at the Fourth Economics of Media Bias Workshop in Berlin and the Michigan Symposium on Media and Politics; and Brandice Canes-Wrone, Matthew Gentzkow, Nathan Kalmoe, Kevin Munger, Anselm Hager, Mark Kayser, Bernhard Wessels, and Fabrizio Gilardi for helpful feedback. We especially thank the editor and five anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. C.A.B. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

*We also recorded clicks on the email newsletter subscription links shown to respondents assigned to either treatment group. Compliance by this measure was high (76% in the Fox News group and 78% in the HuffPost group), although we could not verify the extent to which clicks led to actual sign-ups.

†In SI Appendix, we conduct an analysis of the minimum detectable effect for each treatment–outcome combination expressed in standardized (Cohen’s ) terms.

‡As we note in SI Appendix, it is possible that the compliers additionally differ from the full sample in unobserved ways. Beyond this, it is important to recall that our sample is itself a subsample of respondents willing to share private web data with researchers.

§See SI Appendix for details on how we chose these sites and the full text of the encouragements.

¶Secure transactions and passwords are not collected or shared with researchers in the first place, and YouGov performs an initial scrub of personally identifying information before delivering the data.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2013464118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Data files and scripts necessary to replicate the results in this article are available at the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/NetDem-USC/homepage-experiment (59). Preanalysis plan is available at https://osf.io/zj65h.

References

- 1.Morozov E., The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom (PublicAffairs, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tufekci Z., Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest (Yale University Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakshy E., Messing S., Adamic L. A., Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 348, 1130–1132 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grinberg N., Joseph K., Friedland L., Swire-Thompson B., Lazer D., Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 US presidential election. Science 363, 374–378 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guess A. M., Nyhan B., Reifler J., Exposure to untrustworthy websites in the 2016 US election. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 472–480 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentzkow M., Shapiro J. M., Ideological segregation online and offline. Q. J. Econ. 126, 1799–1839 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flaxman S., Goel S., Rao J. M., Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. Publ. Opin. Q. 80 (S1), 298–320 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guess A. M., (Almost) everything in moderation: New evidence on Americans’ online media diets. Am. J. Polit. Sci., 10.1111/ajps.12589 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyengar S., Kinder D. R., News that Matters: Television and American Opinion (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaines B. J., Kuklinski J. H., Experimental estimation of heterogeneous treatment effects related to self-selection. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55, 724–736 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arceneaux K., Johnson M., Changing Minds or Changing Channels?: Partisan News in an Age of Choice (Chicago Studies in American Politics, University of Chicago Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Benedictis-Kessner J., Baum M. A., Berinsky A. J., Yamamoto T., Persuading the enemy: Estimating the persuasive effects of partisan media with the preference-incorporating choice and assignment design. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 902–916 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prior M., Improving media effects research through better measurement of news exposure. J. Polit. 71, 893–908 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guess A. M., Measure for measure: An experimental test of online political media exposure. Polit. Anal. 23, 59–75 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett W., Iyengar S., A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. J. Commun. 58, 707–731 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazarsfeld P. F., Berelson B., Gaudet H., The People’s Choice: How the Voter Makes up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign (Columbia University Press, New York, 1944). [Google Scholar]

- 17.DellaVigna S., Kaplan E., The Fox News effect: Media bias and voting. Q. J. Econ. 122, 1187–1234 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber A. S., Karlan D., Bergan D., Does the media matter? A field experiment measuring the effect of newspapers on voting behavior and political opinions. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 1, 35–52 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopkins D. J., Ladd J. M., The consequences of broader media choice: Evidence from the expansion of Fox News. Qu. J. Polit. Sci. 9, 115–135 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin G. J., Yurukoglu A., Bias in cable news: Persuasion and polarization. Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 2565–2599 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thaler R. H., Sunstein C. R., Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (Penguin, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barberá P., et al. , Who leads? Who follows? Measuring issue attention and agenda setting by legislators and the mass public using social media data. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 883–901 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King G., Schneer B., White A., How the news media activate public expression and influence national agendas. Science 358, 776–780 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell A. “Americans still prefer watching to reading the news – and mostly still through television” (Pew Research Center, December 3, 2018). https://www.journalism.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2018/12/PJ_2018.12.03_read-watch-listen_FINAL1.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaller J. R., The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge University Press, New York, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenz G. S., Follow the Leader? How Voters Respond to Politicians’ Policies and Performance (University of Chicago Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bail C. A., et al. , Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9216–9221 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Druckman J. N., Gubitz S., Lloyd A. M., Levendusky M. S., How incivility on partisan media (de) polarizes the electorate. J. Polit. 81, 291–295 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levendusky M. S., Malhotra N., (Mis) perceptions of partisan polarization in the American public. Publ. Opin. Q. 80 (S1), 378–391 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ladd J., Why Americans Hate the Media and How It Matters (Princeton University Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jurkowitz M., Mitchell A., Shearer E., Walker M., “U.S. media polarization and the 2020 election: A nation divided” (Pew Research Center, January 24, 2020). https://www.journalism.org/2020/01/24/u-s-media-polarization-and-the-2020-election-a-nation-divided/. Accessed June 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnidge M., et al. , Politically motivated selective exposure and perceived media bias. Commun. Res. 47, 0093650217713066 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vallone R. P., Ross L., Lepper M. R., The hostile media phenomenon: Biased perception and perceptions of media bias in coverage of the Beirut massacre. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 49, 577 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunther A. C., Schmitt K., Mapping boundaries of the hostile media effect. J. Commun. 54, 55–70 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perryman M. R., Biased gatekeepers? Partisan perceptions of media attention in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Journal. Stud. 20, 1–18 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arceneaux K., Johnson M., Murphy C., Polarized political communication, oppositional media hostility, and selective exposure. J. Polit. 74, 174–186 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price V., Zaller J., Who gets the news? Alternative measures of news reception and their implications for research. Publ. Opin. Q. 57, 133–164 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albertson B., Lawrence A., After the credits roll: The long-term effects of educational television on public knowledge and attitudes. Am. Polit. Res. 37, 275–300 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levy R., Social media, news consumption, and polarization: Evidence from a field experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 111, 831–870 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benkler Y., Faris R., Roberts H., Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics (Oxford University Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sehgal U., Jon Stewart’s rare, unexpectedly serious interview with Fox News (2011). https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2011/06/jon-stewart-makes-rare-appearance-fox-new-call-its-viewers-misinformed/351904/. Accessed 9 March 2021.

- 42.Kelley M. B., Study: Watching only Fox News makes you less informed than watching no news at all (2012). https://www.businessinsider.com/study-watching-fox-news-makes-you-less-informed-than-watching-no-news-at-all-2012-5. Accessed 9 March 2021.

- 43.Kalla J. L., Broockman D. E., The minimal persuasive effects of campaign contact in general elections: Evidence from 49 field experiments. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112, 148–166 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coppock A., Hill S. J., Vavreck L., The small effects of political advertising are small regardless of context, message, sender, or receiver: Evidence from 59 real-time randomized experiments. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc4046 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munzert S., Barberá P., Guess A., Yang J., Do online voter guides empower citizens? Evidence from a field experiment with digital trace data. Publ. Opin. Q., 10.1093/poq/nfaa037 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Druckman J. N., Leeper T. J., Learning more from political communication experiments: Pretreatment and its effects. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 875–896 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levendusky M., How Partisan Media Polarize America (University of Chicago Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eady G., Nagler J., Guess A., Zilinsky J., Tucker J. A., How many people live in political bubbles on social media? Evidence from linked survey and Twitter data. Sage Open 9, 2158244019832705 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scharkow M., Mangold F., Stier S., Breuer J., How social network sites and other online intermediaries increase exposure to news. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 2761–2763 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sunstein C. R., #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media (Princeton University Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hargittai E., Micheli M., “Internet skills and why they matter” in Society and the Internet: How Networks of Information and Communication are Changing Our Lives, Graham M., Dutton W. H., Eds. (Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lorenz-Spreen P., Lewandowsky S., Sunstein C. R., Hertwig R., How behavioural sciences can promote truth, autonomy and democratic discourse online. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 1102–1109 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prior M., Post-Broadcast Democracy: How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections (Cambridge University Press, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rivers D., Sampling for web surveys. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.468.9645&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 12 March 2021.

- 55.Lin W., Agnostic notes on regression adjustments to experimental data: Reexamining freedman’s critique. Ann. Appl. Stat. 7, 295, 318 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerber A. S., Green D. P., Field Experiments: Design, Analysis, and Interpretation (W. W. Norton, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stier S., Breuer J., Siegers P., Thorson K., Integrating survey data and digital trace data: Key issues in developing an emerging field. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 38, 503–516 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Menchen-Trevino E., “Digital trace data and social research: A proactive research ethics” in The Oxford Handbook of Networked Communication, Welles B. F., González-Bailón S., Eds. (Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guess A., Data from “The consequences of online partisan media.” GitHub. https://github.com/NetDem-USC/homepage-experiment. Deposited 9 March 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data files and scripts necessary to replicate the results in this article are available at the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/NetDem-USC/homepage-experiment (59). Preanalysis plan is available at https://osf.io/zj65h.