Significance

Individual cells within a community often need to respond to changing environmental conditions at the population level. Accordingly, bacteria have evolved a large array of regulatory mechanisms that enable them to quickly reprogram behavior in a coordinated manner. Unraveling these mechanisms provides valuable information regarding collective behavior in the bacterial world. Herein, we show that by modulating the environmental pH levels, bacterial colonies reflect the nutritional status of the environment and accordingly regulate a collective form of surface motility. We further show that in mixed populations, neighboring bacterial species can change the outcome of such regulation through pH modification and thus affect the community’s spatial organization.

Keywords: carbon catabolite repression, Paenibacillus spp., pH modulation, swarming

Abstract

Bacteria have evolved a diverse array of signaling pathways that enable them to quickly respond to environmental changes. Understanding how these pathways reflect environmental conditions and produce an orchestrated response is an ongoing challenge. Herein, we present a role for collective modifications of environmental pH carried out by microbial colonies living on a surface. We show that by collectively adjusting the local pH value, Paenibacillus spp., specifically, regulate their swarming motility. Moreover, we show that such pH-dependent regulation can converge with the carbon repression pathway to down-regulate flagellin expression and inhibit swarming in the presence of glucose. Interestingly, our results demonstrate that the observed glucose-dependent swarming repression is not mediated by the glucose molecule per se, as commonly thought to occur in carbon repression pathways, but rather is governed by a decrease in pH due to glucose metabolism. In fact, modification of the environmental pH by neighboring bacterial species could override this glucose-dependent repression and induce swarming of Paenibacillus spp. away from a glucose-rich area. Our results suggest that bacteria can use local pH modulations to reflect nutrient availability and link individual bacterial physiology to macroscale collective behavior.

Carbon catabolite repression (CCR), first described by Jacob and Monod in 1961 (1), earning them the Nobel Prize in 1965, is one of the paradigms of gene regulation in bacteria. This system is usually described in terms of the hierarchical use of carbon sources. However, the identification of a growing list of genes, which in turn govern other physiological activities such as virulence, sporulation, motility, and adhesion, has expanded its regulatory role (2–8). The mechanism of the CCR pathway has been mainly studied in the Gram-negative model bacterium Escherichia coli and the Gram-positive model bacterium Bacillus subtilis (for review, see ref. 8). In both bacterial species, growth on glucose results in the inhibition of specific genes; however, the molecular mechanism via which the CCR is implemented differs. In E. coli, the CCR pathway exerts its regulation through affecting the cellular levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which in turn govern the activity of the transcriptional regulator cAMP-receptor protein (9, 10). In B. subtilis, the CCR system regulates the transcription of genes directly through the catabolite control protein A, which belongs to the LacI/GalR family of regulators (11, 12). In both model bacteria, the system is known to be primarily activated by the phosphoenolpyruvate‐carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS) that couples glucose transport to its phosphorylation (13). However, reports showing CCR activation by carbon sources that are not imported by way of the PTS suggest that additional signals related to carbon acquisition and metabolism exist (14–16). An example of such a signal, which was shown to cross-regulate various metabolic pathways, is α-ketoglutarate (17–19), and it is likely that additional regulatory compounds exist.

Several studies have reported that glucose inhibits motility through the CCR pathway in a variety of bacterial species. For instance, early studies by Adler and Templeton reported that glucose inhibits E. coli motility (20). Subsequent studies by Silverman and Simon showed that the operon of flagellar synthesis in these bacteria is sensitive to catabolite repression (21). Stella et al. (5) showed that flagella production in Serratia marcescens is regulated by the cAMP-dependent catabolite repression system and thus is not active in the presence of glucose. Mendez et al. (2) reported inhibition of gliding motility in the anaerobic pathogen Clostridium perfringens in the presence of glucose due to the activation of CCR, and O’Toole et al. (22) reported an inhibitory effect of glucose on twitching motility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In these studies, in accordance with the mechanism of CCR, the glucose molecule itself was reported to exert the inhibitory cascade. Here, we examined the effect of glucose and pH levels on the swarming behavior of Paenibacillus spp. Our results suggest that the decrease in pH values caused by the metabolism of glucose, and not necessarily the carbon molecule per se, could be responsible for the inhibition. Our results also provide insights regarding the involvement of pH shifts in the regulation of surface motility of proficient swarming bacteria, suggesting that environmental pH modifications could serve as signals for social organization in bacteria.

Results and Discussion

Glucose Down-Regulates Flagellin Expression and Inhibits Swarming of Paenibacillus spp. YH6.

When grown on rich Lysogeny broth (LB) with 1.5% agar (LBA) supplemented with 1% glucose (LBAG), the swarming of Paenibacillus sp. YH6 (hereinafter: “Paenibacillus sp.”) was completely suppressed (Fig. 1 A and B). Growth on lower concentrations of glucose (0.1% glucose) resulted in delayed swarming, which commenced only when the glucose was consumed (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Growth measurements of Paenibacillus sp. in LB with or without 1% glucose indicated that, as opposed to the reported effect of glucose on growth of Paenibacillus sp. in M9 media (23, 24), addition of glucose to LB media did not inhibit growth and actually resulted in increased growth yield (Fig. 1C), thus suggesting that the observed swarming inhibition was not a result of a growth defect. Given that several studies have reported inhibition of bacterial motility through the CCR pathway (2, 5, 12, 20–22), an explanation for the inhibitory effect of glucose could be related to inhibition of expression of flagellar related genes. Indeed, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of the hag gene that encodes flagellin demonstrated a significant reduction in its expression level when Paenibacillus sp. was grown on LBAG plates (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Effect of glucose on Paenibacillus sp. motility. (A) Representative images of Paenibacillus sp. colonies inoculated on 1.5% LBA plates, with or without 1% glucose (LBAG and LBA, respectively). Images were taken at 72 h postinoculation. (B) Swarming area of Paenibacillus sp. at 48 h postinoculation. (C) Growth of Paenibacillus sp. in liquid LB medium with or without 1% glucose (LBG and LB, respectively), y-axis presented in log2. (D) qRT-PCR of Paenibacillus sp. flagellin (hag) gene expression in LBA and LBAG. Mean ± SEM; n = 12; Student’s t test was performed. ****P < 0.0001 in B; ***P < 0.001 in D. The plate diameter was 9 cm.

Notably, in contrast to the glucose-dependent suppression of swarming motility, spreading of Paenibacillus sp. by swimming was not inhibited in the presence of glucose (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). As swarming in many bacterial species requires a state of hyper-flagellation (25–27), the low levels of the flagellin-encoding gene, obtained in our qRT-PCR analyses, suggest that the inhibition of swarming in the presence of glucose was associated with suppression of hyperflagellation and not with inhibition of normal flagellar activity. Accordingly, qRT-PCR analyses of hag expression in liquid LB media with glucose (LBG) did not differ significantly from expression levels found in LB media without glucose (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Volatiles Produced by Xanthomonas perforans Override Glucose Inhibition.

Based on previous findings reported by our laboratory demonstrating a strong inducing effect of volatiles produced by X. perforans on swarming motility of Paenibacillus sp. (28), we opted to examine the outcome of the interaction between these two bacterial species on LBAG. Consistent with the strong effect we found in our previous study (28), exposure to X. perforans volatiles resulted in induced swarming and increased expression of flagellin, even when Paenibacillus sp. was grown on LBAG plates (Fig. 2). The fact that Paenibacillus sp. cells swarmed in the presence of glucose when exposed to X. perforans volatiles indicated that the cells failed to sense that they were in a glucose-rich environment. This could imply that pathways other than those described in the classical glucose-dependent CCR are involved in coordinating gene expression with glucose metabolism. Several studies that support this idea have suggested that cellular levels of α-ketoglutarate could also affect gene regulation in the CCR pathway (17–19, 29). Intracellular levels of α-ketoglutarate fluctuate according to nitrogen and carbon availability (17). We therefore hypothesized that X. perforans volatiles could override glucose inhibition if they affect the environmental C/N (carbon/nitrogen) ratio. Such an effect could occur through the synthesis of volatile amines, a common feature of several bacterial species (30, 31) that has been shown to play an important role in interspecies bacterial interactions (32–36).

Fig. 2.

Effect of X. perforans volatiles on swarming of Paenibacillus sp. in the presence of glucose. (A) Experiments were carried out using bipartite Petri dishes. Representative images of Paenibacillus sp. colonies inoculated on LBA with 1% glucose media (LBAG) (upper compartment); X. perforans was inoculated on LBA (bottom compartment, right plate). X. perforans was inoculated 24 h prior to Paenibacillus sp. Image was taken 36 h after Paenibacillus sp. inoculation. (B) Swarming area of Paenibacillus sp. on LBAG in the absence (-Xp) and presence (+Xp) of X. perforans. Swarming area was measured at 36 h of post-Paenibacillus sp. inoculation. (C) qRT-PCR of Paenibacillus sp. flagellin (hag) gene expression in the absence (-Xp) and presence (+Xp) of X. perforans. Mean ± SEM; n = 12; Student’s t test was performed. ***P < 0.001 in B and C. The plate diameter was 9 cm.

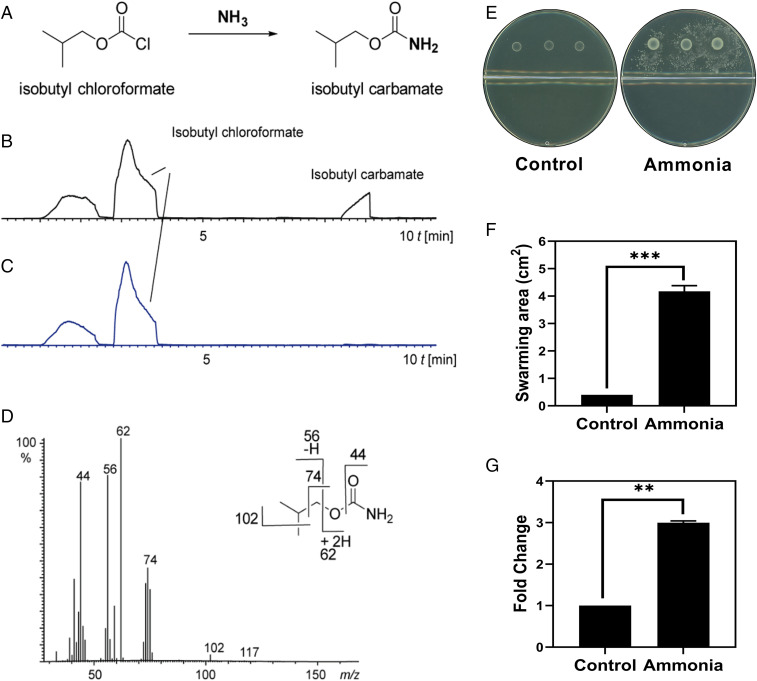

In search of amines in the volatile bouquet of X. perforans, we carried out a specific detection assay for ammonia and other small amines, using a solid-phase microextraction (SPME) method (37). The detection method is based on the reaction of isobutyl chloroformate coating the SPME fiber with ammonia or amines to produce high molecular weight products, easily separated and detected by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). As seen in Fig. 3B, the only product formed from exposure of the derivatized SPME fiber to the X. perforans culture headspace was isobutyl carbamate (formed from reaction of isobutyl chloroformate and ammonia), indicating that ammonia is a volatile amine compound produced by colonies of X. perforans.

Fig. 3.

Involvement of ammonia in swarming induction. (A–D) Detection of ammonia in the headspace of X. perforans cultures. (A) Isobutyl chloroformate reacts with ammonia to produce isobutyl carbamate. (B) Total ion chromatogram of a SPME derivatization experiment with X. perforans culture, showing the occurrence of an isobutyl carbamate peak. (C) Control experiment with an agar plate without X. perforans culture. (D) Electron ionization mass spectrum of isobutyl carbamate and major fragments, verifying the structure. (E–G) Effect of ammonia vapors on swarming of Paenibacillus sp. (E) Experiments were carried out using bipartite Petri dishes. Representative images of Paenibacillus sp. colonies inoculated on LBAG (upper compartment); X. perforans was inoculated on LBA (bottom compartment). Ten microliters of 32% ammonium hydroxide (i.e., 100 mM ammonia) were placed on the bottom compartment 24 h prior to Paenibacillus sp. Image was taken 36 h after Paenibacillus sp. inoculation. (F) Swarming area of Paenibacillus sp. on LBAG in the absence (control) and presence (ammonia) of ammonia. X. perforans serves as positive control. Swarming area was measured at 36 h after Paenibacillus sp. inoculation. (G) qRT-PCR of Paenibacillus sp. flagellin (hag) gene expression in the absence (Control) and presence (Ammonia) of ammonia. Mean ± SEM; n = 10. In F and G, Student’s t test was performed. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01. The plate diameter was 9 cm.

Exposure of Paenibacillus sp. cells to vapors of ammonium hydroxide resulted in induced swarming and increased expression of flagellin even when Paenibacillus sp. was grown on LBAG (Fig. 3 E–G). This corroborates our hypothesis that a volatile amine compound is responsible for the effect overriding swarming inhibition by glucose.

pH Values Mediate Glucose-Dependent Swarming Inhibition in Paenibacillus sp.

The countering effects that glucose and ammonia exert on the swarming of Paenibacillus sp. could stem either from their effect on the C/N ratio in the environment, or from the countering effects that these molecules have on the environmental pH values. When grown on glucose, bacteria often decrease the pH value of their surroundings due to the secretion of acidic metabolites (38). Such a decrease in pH values was also observed for Paenibacillus sp. grown on LBAG (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Ion chromatography mass spectrometry (IC-MS) analysis of spent agar media from Paenibacillus sp. cultures grown on LBAG verified the production of lactic and pyruvic acids, which would account for the decrease in pH (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

To discern whether the observed swarming induction by ammonia is caused by the impact on the C/N ratio or the effect on the pH, we grew Paenibacillus sp. on LBAG and supplemented with the following compounds: 1) LBAG with 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) at pH 8 (increases initial pH but does not affect the initial C/N ratio), 2) LBAG with NaOH at pH 8 (increases initial pH but does not affect the initial C/N ratio), and 3) LBAG with 100 mM ammonium chloride (affects the initial C/N ratio but does not affect the initial pH levels). Our results show that similarly to the effect of ammonia, growth on high pH—obtained either by addition of NaOH or MOPS buffer at pH 8—could override swarming inhibition by glucose (Fig. 4). However, addition of ammonium chloride, which affects the C/N ratio but does not increase pH, could not eliminate the inhibitory effect of glucose on swarming and hag expression. These results suggest that the inhibition of swarming in the presence of glucose is mediated by the low pH resulting from glucose metabolism and not by the glucose molecule per se. Accordingly, when grown on LBA MOPS pH 6.0, swarming of Paenibacillus sp. was inhibited (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of pH on glucose-dependent swarming inhibition of Paenibacillus sp. (A) Representative images of Paenibacillus sp. colonies inoculated on 1.5% LBA with 1% glucose (LBAG), LBAG + 100 mM Ammonium chloride (LBAG NH4Cl), LBAG + 10 mM NaOH to adjust the pH to 8 (LBAG pH8), LBAG + 100 mM MOPS pH8 (LBAG MOPS pH8), and LBA + 100 mM MOPS pH6 (LBA MOPS pH6). Image was taken at 48 h after Paenibacillus sp. inoculation. (B) Swarming area of Paenibacillus sp. colonies at 36 h postinoculation. (C) qRT-PCR of Paenibacillus sp. flagellin (hag) gene expression in LBAG, LBAG NH4Cl, LBAG pH8, LBAG 100 mM MOPS pH8, and LBA 100 mM MOPS pH6. Mean ± SEM; n = 5; the lowercase letter is used to denote significant differences in treatments using Tukey’s test at 0.05% significance level. Plates were supplemented with the pH indicator phenol-red (0.018 g/L); yellow color indicates pH ≤7; pink color indicates pH ≥8. The plate diameter was 9 cm.

Dynamic pH Changes Are Involved in Surface Sensing of Paenibacillus spp. and Proteus mirabilis.

The aforementioned data indicated that specific pH levels regulate swarming behavior in Paenibacillus sp. colonies. As swarming is naturally exhibited by Paenibacillus colonies that are not exposed to X. perforans volatiles, we followed the swarming pattern and pH values of Paenibacillus sp. colonies inoculated on LBA without exposing them to X. perforans. Using plates supplemented with the pH indicator phenol red, we observed that Paenibacillus sp. colonies increased the pH levels of their surroundings just before swarming commencement. Notably, similar behavior was exhibited by additional Paenibacillus spp., as well as by P. mirabilis colonies, all of which increased the local pH value upon swarming commencement (Fig. 5 and Table 1). It is important to note that this increase in pH was not observed in liquid LB media, which maintained pH values ranging from 6.5 to 7 throughout the growth of Paenibacillus spp. and P. mirabilis cultures. Thus, the pH change observed on agar plates was specifically associated with growth on a surface. Analytic methods using headspace derivatization for identification of potential alkalinizing compounds such as ammonia or small alkylamines, as well as carbamate derivatization methods coupled with GC-MS for detection of water-soluble small basic compounds, could not detect the alkalinizing factor, thus indicating that the pathway involved with the alkalization of the agar media by Paenibacillus sp. differs from that identified in X. perforans. Future large-scale metabolomic studies aimed at identifying the various metabolites produced in solid compared to liquid media are required in order to identify the alkalinizing substance involved in swarming induction of Paenibacillus sp.

Fig. 5.

Swarming of Paenibacillus sp. and P. mirabilis colonies inoculated on LBA with phenol red. (A) Representative images of Paenibacillus sp. colonies inoculated on 1.5% LBA plates with phenol red as pH indicator. The left image was taken at ∼18 h before swarming commenced colony; the right image was taken at ∼48 h. (B) P. mirabilis was inoculated on rich 1.5% LBA plates supplemented with 0.018 g/L phenol red. Images were taken at 4 h (Left) and 8 h (Right) after P. mirabilis inoculation. Plate diameter 9 cm. Yellow color indicates pH ≤7, pink color indicates pH ≥8.

Table 1.

Swarming behavior of selected bacterial species

| Bacteria (surface motility) | Increase pH in liquid media | Increase pH in solid media | Surface motility with 1% glucose |

| Paenibacillus YH6 (swarming) | No | Yes | No |

| Paenibacillus vortex (swarming) | No | Yes | No |

| Paenibacillus dendritiformis (swarming) | No | Yes | No |

| Paenibacillus glucanolyticus | No | Yes | No |

| Escherichia coli K12 (swarming) | No | Yes | Yes |

| Bacillus subtilis (swarming) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Serratia marcescens (swarming) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Proteus mirabilis (swarming) | No | Yes | Delayed |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (swarming+ twitching) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The fact that Paenibacillus sp. cells increased the environmental pH levels only when grown on solid media suggests that surface-dependent activation of metabolic or signaling pathways occurred. Liquid chromatograph–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analyses of free amino acids at various time points during Paenibacillus sp. growth detected differences in the metabolism of several amino acids in liquid compared to solid LB media, with the most pronounced difference being in the metabolism of proline (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). An increase in the concentration of proline during bacterial growth was detected when bacterial cultures were grown on solid surfaces but not in liquid LB media (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Interestingly, the observed surface-dependent production of proline was inhibited in the presence of glucose, indicating the possible involvement of the CCR pathway. Moreover, increasing the pH by NaOH could override the glucose dependent inhibition of proline production (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), further signifying the role that pH holds in the regulation of the CCR pathway. In this regard, it should be noted that addition of proline to LBAG plates did not induce swarming and could not override glucose inhibition (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), thus indicating that proline accumulation is not the cause for swarming induction, but more likely a byproduct of the underlying mechanism which requires surface contact. It is difficult to determine whether the observed differences in amino acid metabolism occurred due to the induction of a specific signaling pathway initiated upon surface sensing, or as a byproduct of the change in diffusion rate of metabolites and oxygen on solid media. It is likely that both are possible, as multiple stimuli affect bacterial behavior on solid media. These stimuli range from mechanical loads on appendages, such as flagella or pilli, to alteration of metabolic pathways responding to distinct surface-dependent conditions and nutrients (39–42).

In order to determine the prevalence of pH-regulated swarming in other bacterial species, we examined the behavior of additional bacterial species exhibiting surface motility in the form of swarming (Table 1). All tested bacteria increased their pH when grown on agar plates. However, this phenomenon could be attributed to surface sensing only for Paenibacillus spp., P. mirabilis (Fig. 5), and E. coli, as all other examined species increased the pH value of their environment in both liquid and solid media. Examination of the effect of glucose on surface motility of the tested bacterial species indicated that glucose 1) induced the swarming of E. coli; 2) had no effect (either negative or positive) on the swarming of Serratia marcescens, P. aeruginosa, or B. subtilis; and 3) had a negative effect on the swarming of Paenibacillus spp. and P. mirabilis (Table 1). Although E. coli exhibited surface-dependent alkalization when inoculated on LBA plates, the colonies’ responses to glucose significantly differed from those of P. mirabilis and Paenibacillus spp., as glucose positively affected swarming of E. coli, which could not swarm on LB 0.5% agar unless supplemented with glucose. Interestingly, a study examining the effect of pH on gene expression in E. coli K-12 found that expression of E. coli flagellar genes was inhibited in high pH (i.e., pH 9) and induced in low pH (i.e., pH 5) (43).

It should be noted that the inhibitory effect of glucose on the swarming of P. mirabilis colonies was transient and that eventually P. mirabilis colonies succeeded to swarm in the presence of glucose (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). However, time-lapse movies of P. mirabilis swarming revealed that despite the presence of 1% glucose, the colony succeeded to increase the environmental pH while swarming on LBAG (Movie S1). Such ability, which was not exhibited by the Paenibacillus species (Movie S2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7), indicates the importance of pH shifts for swarming of Paenibacillus spp. and P. mirabilis. Accordingly, a phenol red–supplemented bipartite plate assay examining the effect of X. perforans on Paenibacillus sp. showed that swarming commencement of Paenibacillus sp. colonies on LBAG occurred only alongside the pH increase caused by X. perforans volatiles (Movie S3). It is interesting to note that of the examined species, only those considered proficient swarmers (i.e., able to swarm on >1% agar) exhibited swarming dependency under pH increase, as well as glucose-dependent swarming inhibition. These results point to a difference in the swarming mechanism of proficient and nonproficient swarmers. However, examination of additional proficient swarmers is required to understand the scale of this phenomenon.

X. perforans Gains Accesses to a Glucose-Rich Area by Affecting the Swarming of Paenibacillus sp.

The role that bacterial volatiles play in shaping the structure and pattern of microbial population has gained increased attention in the past decade (32, 44–47). In order to examine the effect of the interaction between X. perforans and Paenibacillus sp. on their spatial distribution, we constructed a custom-made Petri dish that contains an area of LBAG, bordering an area with plain LBA. Our results show that the outcome of this interaction holds a benefit for X. perforans; apparently, the volatiles produced by X. perforans could manipulate Paenibacillus sp. to move away from the glucose-rich area and toward X. perforans colonies. The slimy swarm of Paenibacillus sp. cells moving between the glucose-rich area and X. perforans colonies created a path between the two areas of the Petri dish. This path was utilized by X. perforans cells as means of access to the glucose part of the dish, otherwise not accessible to the nonswarming X. perforans colonies (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Coinoculation of X. perforans and Paenibacillus sp. on custom-made LBA–LBAG swarm plates. (A) Schematic representation of the interaction between X. perforans (orange) and Paenibacillus sp. (light blue) demonstrating how X. perforans cells inoculated on LBA gain accesses to a glucose-rich area (LBAG) by exploiting the swarming of Paenibacillus sp. (B) Representative images of Paenibacillus sp. (PYH6) and X. perforans (XP) inoculated on custom-made LBA–LBAG. Left plate X. perforans inoculated on LBA (Bottom) and Paenibacillus sp. inoculated on LBAG (Top); right plate X. perforans inoculated on LBA (Bottom), and the top part contains LBAG without bacteria. Black horizontal lines indicate place of inoculation. Images taken at plates at 60 h after bacterial inoculation. The plate diameter was 9 cm.

Summary

For many years, glucose and other rapidly metabolized sugars have been proposed to regulate gene transcription through the canonical pathway of catabolite repression. The idea that pathways other than those involving PTS could activate CCR was raised by Ullmann et al. (48), who searched for catabolite-modulating factors other than cAMP. Recently, elegant studies published by Doucette et al. (19) and You et al. (18) demonstrated that in E. coli, α-ketoacids such as α-ketoglutarate could directly regulate the CCR system. As α-ketoglutarate is part of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, as well as involved in nitrogen assimilation, it was suggested that this molecule reflects the carbon-nitrogen balance of the nutrients in the environment, and thereby activates the CCR’s regulatory pathway. Here we suggest that similarly to α-ketoacids, pH levels might also reflect the environment’s C/N status. It is yet to be determined whether pH levels directly regulate the CCR pathway through a pH sensor or indirectly through their effect on specific metabolic pathways. The remarkable ability of bacteria to integrate complex and dynamic inputs reflects their use of overlapping regulatory systems and suggests that both options could simultaneously exist. Regardless, our results clearly demonstrate that pH-dependent regulation is positioned at a key metabolic intersection in the CCR pathway, with the possibility of overriding the regulatory activity of the glucose molecule itself.

The fact that the glucose-dependent inhibition of motility was effective only on solid surfaces can be explained by the finding that, at least in the cases of Paenibacillus spp. and P. mirabilis, dynamic pH changes govern transitions between swarming phases. Inhibition of these dynamic changes by high carbon, and hence low pH, abolish surface motility and confine the bacteria within a favorable environment. Such a pathway serves as a simple and generalized way of monitoring the environment’s nutritional status.

We suggest that, similarly to quorum sensing, local modifications of pH levels carried out by microbial cells in unison can be used as signals connecting individual physiology to macroscale collective behaviors. Moreover, we show that these signals can be manipulated by neighboring colonies, thereby affecting the spatial organization of a mixed population.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are described in SI Appendix, Table S1. Unless stated otherwise, bacterial strains were grown in LB (Difco) under constant shaking (250 rpm) or LBA agar (LB containing 15 g/l agar) at 30 °C. All strains were maintained as glycerol stocks at −80 °C.

Glucose Media.

LB or LBA were supplemented with glucose to a final concentration of 1% (LBG or LBAG, respectively).

Buffered Media.

3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to LB or LBA at a final concentration of 100 mM. For experiments requiring pH 8, the pH was adjusted by addition of NaOH; for experiments requiring pH 6, the pH was adjusted by addition of HCl.

Swarming Media.

Swarming plates were prepared as described in ref. 49 with minor modifications. A total of 15 mL molten LBA were poured into a 90 mm diameter polystyrene Petri dish. Prior to bacterial inoculation, swarm plates were typically allowed to cure in the laminar hood for 5 min with the lid open and a further 24 h with the lid closed for drying excess liquid. The same batch of medium was used for each experiment.

Combined LBA–LBAG Swarm Plates.

Hitchhiking of X. perforans on Paenibacillus sp. YH6 was examined on custom-made LBA–LBAG swarm plates (Fig. 6). For this assay, 15 mL LBAG were poured in to the swam plates and allowed to solidify. Half of the solidified medium was removed and replaced with 7.5 mL molten LBA, which was then allowed to solidify. Prior to swarming experiments, plates were treated as described above for swarming media. For swarming analyses, time-lapse images were taken with an Epson Perfection V850 Pro scanner using Vuescan software (version 9.6.43, Hamrick Software).

pH Indicator Plates.

pH indicator phenol red was added to LBA at a final concentration of 0.018 g/L.

Ammonium Chloride Agar Plates.

Ammonium chloride was added to LBAG at a final concentration of 100 mM.

Bacterial Growth Curves.

Two hundred microliters of overnight broth culture (ca.107 cell/mL) diluted at 1:100 in fresh LB or LBG media were inoculated into a 96-well flat-bottom microplate (Costar, Sigma-Aldrich). Medium without bacterial cells served as blank. The plate was incubated at 30 °C, and optical density (OD595) was recorded every 15 min using an automatic microplate reader (Tecan Infinite F200). The plate was shaken for 10 s prior to each reading.

qRT-PCR Analyses.

To check flagellin (hag) gene expression in swarm plates, 7 µl (ca.107 cell/mL) of Paenibacillus sp. broth culture were inoculated at the center of the desired agar plate (i.e., LBA, LBAG, ±MOPS, ±NaOH, ±NH4Cl, ±ammonia, ±X. perforans). Plates were sealed with Parafilm (Bemis) and incubated at 30 °C for ∼48 h. Once Paenibacillus sp. started swarming, cells were collected from the plate by washing with phosphate-buffered saline, and we proceeded with RNA extraction.

To check flagellin gene expression in liquid media, overnight culture of Paenibacillus sp. cells were (ca. 107 cell/mL) washed with phosphate-buffered saline, inoculated into LB and LBG, and incubated at 30 °C for 3 h with shaking at 250 rpm, after which cells were collected for RNA extraction.

Total RNA was extracted using SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega) as per the manufacturer’s protocol, and was subsequently treated with DNase (TURBO DNA-free kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA integrity was tested by agarose gel electrophoresis. Absence of residual genomic DNA contamination in RNA was confirmed by PCR with 16S rDNA amplification. cDNA from 1 μg of total RNA was synthesized using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher). Primers used in the study are listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. qRT-PCR analyses were performed using the StepOnePlusTM Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with green Fast SYBR 2X (Applied Biosystems). The PCR parameters were as follows: initial polymerase activation, 20 s at 95 °C; 40 cycles of 3 s at 95 °C; 30 s at 60 °C; and 15 s at 72 °C. Ten nanograms of template and 200 nM primers were used per reaction. Melt curve analysis was performed to test the specificity of primers. All values reported are given as relative expression of each gene compared to 16S rRNA expression levels.

Exposure of Paenibacillus sp. to X. perforans’ Volatiles.

Unless otherwise stated, experiments were conducted using bipartite Petri plates. These plates prevented direct contact between Paenibacillus sp. and X. perforans colonies, allowing only the transfer of airborne substances between the two compartments of the Petri plates. Conditioned plates were obtained by inoculating 20 µl of X. perforans (ca. 106 cell/mL) into the compartment containing LBA media 24 h prior to inoculation of Paenibacillus sp. in the opposite compartment. The control plate was devoid of X. perforans. Paenibacillus sp. colonies exposed plates were examined continuously to check for swarming. Once Paenibacillus sp. began swarming in conditioned agar plates, cells were collected and RNA was extracted.

SPME Analysis.

Ammonia trace analysis was performed by following Lubrano et al.’s (37) protocol to derivatize an 85 μm PA SPME fiber with isobutyl chloroformate. Conditioning of the SPME fiber was carried out by leaving it for 5 min in the gas chromatograph (GC) injector at 250 °C. Afterwards, a manual SPME fiber holder was used to expose the fiber to the headspace of 2 mL isobutyl chloroformate in a 20 mL bottle with a snap-on cap for 1 min. The derivatized fiber was then exposed for 5 min to the headspace of the bacterial culture, which was cultivated in a 5 mL bottle with screw-on cap and septum. Direct injection into the gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (GC-MS) was then executed, and the fiber was exposed in the GC injector.

Water-soluble small basic compounds were analyzed following (50) protocol: 10 µL bacterial culture samples were treated with a mixture of 100 μL water/ethanol/pyridine (60:32:8), and 5 μL ethyl chloroformate (ETC) were added and mixed by briefly shaking the vial. Then 100 μL chloroform containing 5% ETC were added, and derivatives were extracted into organic phase by striking the vial against a pad for about 5 s. The clear organic layer was separated by a syringe and dried with MgSO4. One microliter of an aliquot was injected directly into a GC-MS instrument.

GC-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph equipped with a 30 m analytical column (HP-5MS 30 m × 0.25 mm ID, tf = 0.25 μm). A splitless injection port at 250 °C was used for sample introduction. Temperature program: 50 °C (5 min), then increasing with 5 °C/min to 320 °C (10 min). The helium carrier gas was set to 1.0 mL/min flow rate (constant flow mode). Mass spectrometry was performed with an Agilent 5977A MSD in electron ionization mode at 70 eV.

For analyses of compounds from bacterial agar plates, total agar was excised from whole plates and squeezed through a nylon mesh by gentle centrifugation (1,500 × g for 1 min) for liquid extraction. The liquid was then filtered through a 0.22 μm pore size membrane filter for filtering out bacterial cells.

Analyses of Glucose.

Analysis of glucose in agar extracts and broth samples was carried out using GC-MS. Liquid samples were spiked with an internal standard (mannitol), evaporated to dryness upon a stream of nitrogen, and converted into trimethylsilyl derivatives using N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) in pyridine. For analysis, a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890A) coupled to a mass selective detector (Agilent 5975C MSD) and equipped with a CTC Combi PAL autosampler was used. The mass spectrometer was operated in SIM acquisition mode. The compounds were separated on a capillary column (Rxi-5ms, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm, Restek) using helium as the carrier gas. For quantification of glucose, the calibration curve was prepared at concentrations ranges from 0.1 to 100 µg/mL

LC-MS Analyses of Amino Acids.

Analysis of free amino acids was carried out using the LC-MS/MS system, which consisted of Nexera X2 UPLC (Shimadzu) coupled to QTRAP 6500+ tandem mass spectrometer (Sciex). The samples were spiked with a mixture of isotopically labeled amino acids (purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) before analysis. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ESI MRM acquisition mode. Amino acids were separated on HILIC-Z column (150 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 µm, Agilent Technologies) employing acetonitrile/ammonium formate 100 mM linear gradient.

IC-MS of Organic Anions.

Samples were analyzed on IC-MS system which consisted of Dionex Integrion HPIC ion chromatograph (IC) coupled to Q Exactive Plus hybrid FT mass spectrometer equipped with heated electrospray ionization source (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The IC system consisted of isocratic pump, on-line KOH eluent generator, thermal compartment, autosampler, make-up pump (acetonitrile), autosupressor operated in external water mode, and conductivity detector.

Chromatographic separations of anions were achieved using hydroxide-selective anion-exchange analytical column (AS11 HC, 250 × 2.1 mm, Thermo Scientific). The mass spectrometer was operated in negative ESI ionization mode, ion source parameters were as follows: spray voltage 3 kV, capillary temperature 300 °C, sheath gas rate (arb) 40, and auxiliary gas rate (arb) 10. Mass spectra were acquired in full scan (m/z 60–400) and all ions fragmentation (m/z 50–400) Da acquisition modes at resolving power 70,000. The IC-MS system was controlled and data were analyzed using Xcalibur software.

Exposure of Paenibacillus sp. to Ammonia.

To test for the possible involvement of biogenic ammonia produced by X. perforans in the swarming induction of Paenibacillus sp., synthetic ammonium hydroxide solution was introduced as a source of the volatile compound. 100 mM ammonium hydroxide solution (Merck Millipore) were placed on the opposite compartment to Paenibacillus sp. of a bipartite plate. Ammonia was added 24 h prior to Paenibacillus sp. inoculation, as well as at the time of Paenibacillus sp. inoculation and at 24 h postinoculation. Water served as a control. Seven microliters of Paenibacillus sp. broth culture (ca.107 cell/mL) was inoculated on the agar plate 24 h after placing the ammonium hydroxide solution on the plate’s lid. Upon swarming commencement, bacterial cells were collected and RNA was extracted for qRT-PCR analysis.

Statistical and Image Analysis.

Petri dishes were photographed using an Epson Perfection V850 Pro scanner, time-lapse videos were taken by Vuescan (version 9.6.43, Hamrick Software), and images were analyzed using Fiji software (51). The swarming areas of four independent experiments were measured and treatments were compared with their specific control samples. To compare the various sets, we performed Student’s t test using JMP (version 15).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor S. Ben Yehuda for kindly providing B. subtilis strain 3610, Professor S. Burdman for kindly providing X. perforans 97-2, and Professor Ehud Banin for kindly providing P. aeruginosa. This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation Grant #795/17.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2014346118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Jacob F., Monod J., Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 3, 318–356 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendez M., et al., Carbon catabolite repression of type IV pilus-dependent gliding motility in the anaerobic pathogen Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 190, 48–60 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai H. C., et al., Effect of glucose concentration on swimming motility in enterobacteria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 231, 692–695 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreno M. S., Schneider B. L., Maile R. R., Weyler W., Saier M. H. Jr, Catabolite repression mediated by the CcpA protein in Bacillus subtilis: Novel modes of regulation revealed by whole-genome analyses. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1366–1381 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stella N. A., Kalivoda E. J., O’Dee D. M., Nau G. J., Shanks R. M., Catabolite repression control of flagellum production by Serratia marcescens. Res. Microbiol. 159, 562–568 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almengor A. C., Kinkel T. L., Day S. J., McIver K. S., The catabolite control protein CcpA binds to Pmga and influences expression of the virulence regulator Mga in the group A streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8405–8416 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakravarthy S., et al., Virulence of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 is influenced by the catabolite repression control protein Crc. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 30, 283–294 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Görke B., Stülke J., Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: Many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 613–624 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein W., Rothman-Denes L. B., Hesse J., Adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate as mediator of catabolite repression in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 2300–2304 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishizuka H., Hanamura A., Inada T., Aiba H., Mechanism of the down-regulation of cAMP receptor protein by glucose in Escherichia coli: Role of autoregulation of the crp gene. EMBO J. 13, 3077–3082 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hueck C. J., Hillen W., Catabolite repression in Bacillus subtilis: A global regulatory mechanism for the gram-positive bacteria? Mol. Microbiol. 15, 395–401 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorca G. L., et al., Catabolite repression and activation in Bacillus subtilis: Dependency on CcpA, HPr, and HprK. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7826–7839 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutscher J., Francke C., Postma P. W., How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 939–1031 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogema B. M., et al., Catabolite repression by glucose 6-phosphate, gluconate and lactose in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 857–867 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogema B. M., et al., Inducer exclusion in Escherichia coli by non-PTS substrates: The role of the PEP to pyruvate ratio in determining the phosphorylation state of enzyme IIAGlc. Mol. Microbiol. 30, 487–498 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eppler T., Postma P., Schütz A., Völker U., Boos W., Glycerol-3-phosphate-induced catabolite repression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184, 3044–3052 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huergo L. F., Dixon R., The emergence of 2-oxoglutarate as a master regulator metabolite. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 79, 419–435 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You C., et al., Coordination of bacterial proteome with metabolism by cyclic AMP signalling. Nature 500, 301–306 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doucette C. D., Schwab D. J., Wingreen N. S., Rabinowitz J. D., α-Ketoglutarate coordinates carbon and nitrogen utilization via enzyme I inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 894–901 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adler J., Templeton B., The effect of environmental conditions on the motility of Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 46, 175–184 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman M., Simon M., Characterization of Escherichia coli flagellar mutants that are insensitive to catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 120, 1196–1203 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Toole G. A., Gibbs K. A., Hager P. W., Phibbs P. V. Jr, Kolter R., The global carbon metabolism regulator Crc is a component of a signal transduction pathway required for biofilm development by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 182, 425–431 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratzke C., Denk J., Gore J., Ecological suicide in microbes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 867–872 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ratzke C., Gore J., Modifying and reacting to the environmental pH can drive bacterial interactions. PLoS Biol. 16, e2004248 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kearns D. B., A field guide to bacterial swarming motility. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 634–644 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partridge J. D., Harshey R. M., Swarming: Flexible roaming plans. J. Bacteriol. 195, 909–918 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harshey R. M., Bacterial motility on a surface: Many ways to a common goal. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57, 249–273 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagai E., et al., Surface-motility induction, attraction and hitchhiking between bacterial species promote dispersal on solid surfaces. ISME J. 8, 1147–1151 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniel J., Danchin A., 2-Ketoglutarate as a possible regulatory metabolite involved in cyclic AMP-dependent catabolite repression in Escherichia coli K12. Biochimie 68, 303–310 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz S., Dickschat J. S., Bacterial volatiles: The smell of small organisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 814–842 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weise T., et al., Volatile organic compounds produced by the phytopathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria 85-10. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 8, 579–596 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Audrain B., Farag M. A., Ryu C. M., Ghigo J. M., Role of bacterial volatile compounds in bacterial biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 222–233 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernier S. P., Létoffé S., Delepierre M., Ghigo J. M., Biogenic ammonia modifies antibiotic resistance at a distance in physically separated bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 81, 705–716 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Létoffé S., Audrain B., Bernier S. P., Delepierre M., Ghigo J. M., Aerial exposure to the bacterial volatile compound trimethylamine modifies antibiotic resistance of physically separated bacteria by raising culture medium pH. mBio 5, e00944-13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avalos M., Garbeva P., Raaijmakers J. M., van Wezel G. P., Production of ammonia as a low-cost and long-distance antibiotic strategy by Streptomyces species. ISME J. 14, 569–583 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones S. E., Elliot M. A., Streptomyces exploration: Competition, volatile communication, and new bacterial behaviours. Trends Microbiol. 25, 522–531 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lubrano A. L., Andrews B., Hammond M., Collins G. E., Rose-Pehrsson S., Analysis of ammonium nitrate headspace by on-fiber solid phase microextraction derivatization with gas chromatography mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1429, 8–12 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwami Y., Yamada T., Rate-limiting steps of the glycolytic pathway in the oral bacteria Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguis and the influence of acidic pH on the glucose metabolism. Arch. Oral Biol. 25, 163–169 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hug I., Deshpande S., Sprecher K. S., Pfohl T., Jenal U., Second messenger-mediated tactile response by a bacterial rotary motor. Science 358, 531–534 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellison C. K., et al., Obstruction of pilus retraction stimulates bacterial surface sensing. Science 358, 535–538 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monds R. D., Newell P. D., Gross R. H., O’Toole G. A., Phosphate-dependent modulation of c-di-GMP levels regulates Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 biofilm formation by controlling secretion of the adhesin LapA. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 656–679 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Toole G. A., Wong G. C., Sensational biofilms: Surface sensing in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 30, 139–146 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maurer L. M., Yohannes E., Bondurant S. S., Radmacher M., Slonczewski J. L., pH regulates genes for flagellar motility, catabolism, and oxidative stress in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 187, 304–319 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt R., Cordovez V., de Boer W., Raaijmakers J., Garbeva P., Volatile affairs in microbial interactions. ISME J. 9, 2329–2335 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tyc O., Song C., Dickschat J. S., Vos M., Garbeva P., The ecological role of volatile and soluble secondary metabolites produced by soil bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 25, 280–292 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kai M., et al., Bacterial volatiles and their action potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 81, 1001–1012 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim K. S., Lee S., Ryu C. M., Interspecific bacterial sensing through airborne signals modulates locomotion and drug resistance. Nat. Commun. 4, 1809 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ullmann A., Tillier F., Monod J., Catabolite modulator factor: A possible mediator of catabolite repression in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 73, 3476–3479 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morales-Soto N., et al., Preparation, imaging, and quantification of bacterial surface motility assays. J. Vis. Exp. 98, 52338 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Husek P., Rapid derivatization and gas-chromatographic determination of amino acids. J. Chromatogr. A 552, 289–299 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schindelin J., et al., Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.