The authors highlight notable correlations of severe COVID-19 leukoencephalopathy with reduced diffusivity and obesity, acute renal failure, mild hypernatremia, anemia, and an unusual brain MR imaging white matter lesion distribution pattern.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Patients infected with the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can develop a spectrum of neurological disorders, including a leukoencephalopathy of variable severity. Our aim was to characterize imaging, lab, and clinical correlates of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) leukoencephalopathy, which may provide insight into the SARS-CoV-2 pathophysiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Twenty-seven consecutive patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 who had brain MR imaging following intensive care unit admission were included. Seven (7/27, 26%) developed an unusual pattern of “leukoencephalopathy with reduced diffusivity” on diffusion-weighted MR imaging. The remaining patients did not exhibit this pattern. Clinical and laboratory indices, as well as neuroimaging findings, were compared between groups.

RESULTS:

The reduced-diffusivity group had a significantly higher body mass index (36 versus 28 kg/m2, P < .01). Patients with reduced diffusivity trended toward more frequent acute renal failure (7/7, 100% versus 9/20, 45%; P = .06) and lower estimated glomerular filtration rate values (49 versus 85 mL/min; P = .06) at the time of MRI. Patients with reduced diffusivity also showed lesser mean values of the lowest hemoglobin levels (8.1 versus 10.2 g/dL, P < .05) and higher serum sodium levels (147 versus 139 mmol/L, P = .04) within 24 hours before MR imaging. The reduced-diffusivity group showed a striking and highly reproducible distribution of confluent, predominantly symmetric, supratentorial, and middle cerebellar peduncular white matter lesions (P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Our findings highlight notable correlations between severe COVID-19 leukoencephalopathy with reduced diffusivity and obesity, acute renal failure, mild hypernatremia, anemia, and an unusual brain MR imaging white matter lesion distribution pattern. Together, these observations may shed light on possible SARS-CoV-2 pathophysiologic mechanisms associated with leukoencephalopathy, including borderzone ischemic changes, electrolyte transport disturbances, and silent hypoxia in the setting of the known cytokine storm syndrome that accompanies severe COVID-19.

Among the neurologic disorders associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2)1-3 infection, there have been several reports of diffuse white matter abnormalities, including a “leukoencephalopathy with reduced diffusivity” on diffusion-weighted MR imaging.4 This pattern of severe, bilateral white matter involvement appears to develop late in the course of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in critically ill patients and may be related to the prolonged hypoxemia that these patients experience, often even while asymptomatic.5

Indeed, although leukoencephalopathy can result from a diverse group of genetic, toxic/metabolic, inflammatory, and infectious conditions, several well-described leukoencephalopathy syndromes may have direct relevance to COVID-19 pathophysiology. These disorders, which are associated with distinct clinical features, imaging patterns, and laboratory findings, include but are not limited to both delayed posthypoxic leukoencephalopathy (which often develops days or weeks following an initial, typically catastrophic, global hypoxic event, such as carbon monoxide poisoning, drowning, opioid overdose, or other causes of cardiac arrest)6-9 and sepsis-related leukoencephalopathy (which occurs in critically ill patients and is likely due to deranged blood-brain barrier permeability caused by inflammatory mediators, allowing passage of cytokines and other neurotoxins into the cerebral white matter).10-13

Review of the current literature suggests possible roles for “silent hypoxia” and/or “cytokine storm” in the development of severe COVID-19-related leukoencephalopathy;5,14,15 the paucity of postmortem studies to date contributes to this uncertainty.16 Our purpose, therefore, has been to characterize the clinical, imaging, and laboratory correlates of COVID-19 leukoencephalopathy, which may provide insight into the SARS-CoV-2 pathophysiologic mechanisms of severe white matter cellular injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

We performed an observational, retrospective study of consecutive patients admitted to Massachusetts General Hospital between February 1, 2020, and May 12, 2020. Data collection was approved by the institutional review board and followed Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines. The institutional review board approved a waiver of informed consent for this retrospective analysis.

Patient Cohorts

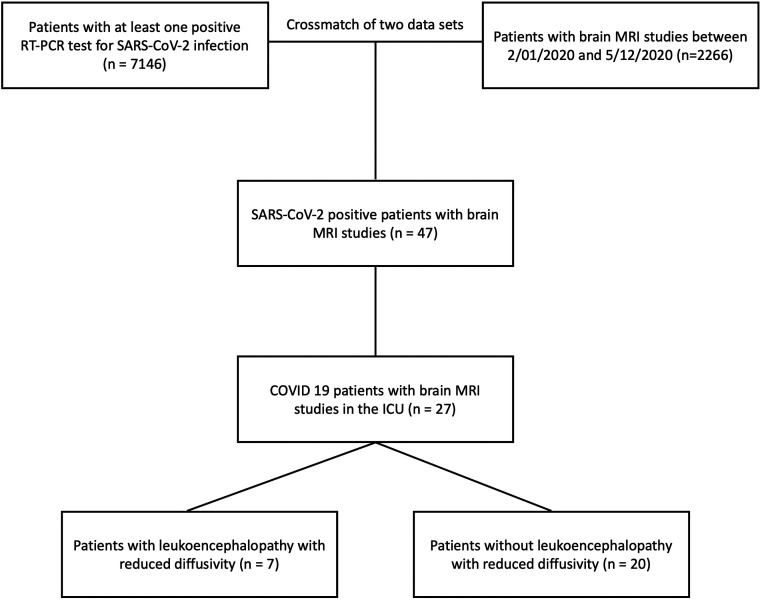

Forty-seven consecutive adult patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 who had brain MR imaging were identified by overlapping an institutional database of adult patients with COVID-19 (n = 7146) and a radiology database of brain MR imaging studies (n = 2266) acquired between February 1, 2020, and May 12, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by at least 1 positive real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test. Inclusion criteria were the following: 1) an assay positive for SARS-CoV-2; 2) age 18 years or older; 3) admission to the intensive care unit (ICU); and 4) brain MR imaging performed >24 hours following ICU admission (Fig 1). Patients not admitted to the ICU, younger than 18 years of age, or having undergone brain MR imaging before their ICU admission were excluded. One patient who had a brain MR imaging at the time of the ICU admission was excluded due to the presence of a pre-existent neurologic condition (suspected central pontine myelinolysis). During data collection, 308 patients (202 men, 66%) with COVID-19 were admitted to the ICU. Of 47 patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 who had brain MR imaging, 28 (28/47, 60%) were admitted to the ICU (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Flow chart of the patient-selection process.

Definition of Baseline and Clinical Variables

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics were recorded, including the duration of symptoms before admission and the number of days from ICU admission to MR imaging acquisition, as well as documentation of organ involvement and standard laboratory data both at the time of ICU admission and within 24 hours before MR imaging acquisition. The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was calculated for every patient at ICU admission. All data were collected using predetermined guidelines from the patients’ electronic medical records. Baseline and ICU data collection was performed blinded to the imaging findings, including the diffusion abnormalities.

Imaging Protocol

The brain MR imaging studies were performed on 1.5T (Excite HDx; GE Healthcare) and 3T (Magnetom Skyra or Prisma; Siemens) scanners. The sequences and acquisition parameters of the typical MR imaging protocol included the following: axial diffusion (voxel size = 1.4 × 1.4 × 5.0 mm, TR = 5000 ms, TE = 96.0 ms, b-values = 0 and 1000 s/mm2), axial SWI (voxel size = 0.8 × 0.8 × 1.8 mm), axial FLAIR (voxel size = 0.4 × 0.4 × 4.0 mm, TR = 9000 ms, TE = 85.0 ms, TI = 2500 ms), axial T1 (voxel size = 0.8 × 0.8 × 4.0 mm, TR = 220 ms, TE = 2.46 ms), sagittal MPRAGE (voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm, TR = 2530 ms, multiple TE values), and axial T2 BLADE (Siemens) (voxel size = 0.7 × 0.7 × 7.0 mm, TR = 5500 ms, TE = 17 ms). Patients without gadolinium contraindications were administered 0.1 mmol/kg of gadoterate meglumine (Dotarem; Guerbet). The following sequences were acquired following contrast administration: axial T1-2D (voxel size = 0.8 × 0.8 × 4.0 mm, TR = 220 ms, TE = 2.46 ms) and sagittal MPRAGE (voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm, TR = 2530 ms, multiple TE values).

Imaging Evaluation

Imaging was reviewed using the PACS by 2 neuroradiologists (O.R., M.M.), blinded to the clinical and laboratory findings. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Patients were dichotomized into 2 discrete groups: those with-versus-without “leukoencephalopathy with reduced diffusivity,” based on the presence or absence of white matter lesions with reduced diffusivity not consistent with an established pattern of ischemic infarction. The extent of supra- and infratentorial WM involvement was qualitatively graded for each patient on the basis of a 4-point Likert score (0 = normal, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe). The anatomic distribution of white matter signal abnormalities was recorded. The presence and number of microhemorrhages were assessed on SWI sequences when available (n = 24) or on gradient recalled-echo sequences (n = 3). Additional neuroimaging findings such as abnormal gray matter signal or intracranial enhancement were collected.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to summarize categoric variables as percentages and continuous variables using means and proportions, range, and 95% confidence intervals. Q-Q plots and Shapiro-Wilk tests were implemented for testing normality. Nonparametric data were described using median and interquartile range. For comparison of means of continuous variables with normal distribution, the Student t test was used. The Mann-Whitney U test was chosen for comparison of nonparametric variables. The Fisher exact test was used to analyze the association of clinical and laboratory findings between the groups with-versus-without reduced diffusivity. Differences and 95% confidence intervals were estimated using the t test for all variables reported. P values <.05 were considered significant. Analyses were conducted using SPSS, Version 24 (IBM).

RESULTS

Patient Cohort Characteristics

Twenty-seven patients (20/27 men, 74%; mean age, 63 years; 95% CI, 57–69 years) were included in the analysis. Seven (7/27, 26%) were identified as having leukoencephalopathy with reduced diffusivity (5/7 men, 71%; mean age, 63 years; 95% CI, 55–71 years); the remaining 20 in the control group did not exhibit this pattern (15/20 men, 75%; mean age, 63 years; 95% CI, 58–69 years) (Table 1 in the Online Supplemental Data). There were no significant differences in the percentage of Asian (0% vs. 5%), Black/African American (14% vs. 30%), White (29% vs. 30%), or Hispanic (57% vs. 35%) between the reduced diffusivity and control groups. The patients with reduced diffusivity compared with the control group had a significantly higher BMI (36 versus 28 kg/m2, P < .01). Other baseline characteristics, including prior tobacco use, concurrent illnesses, symptoms before admission, previous cardiac arrest, and number of days symptomatic (including dyspnea), were similar per the Online Supplemental Data. Except for a single patient in the control group, all patients were intubated at ICU admission. One patient in the control group (1/20, 5%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Four patients in the reduced-diffusivity group and 5 in the control group were treated with nitric oxide (4/7, 57%, versus 5/20, 25%; P = .17). The most common comorbidities were obstructive sleep apnea (5/7, 71.4%, versus 14/20, 70%; P = .26), diabetes (4/7, 57%, versus 8/20, 40%; P = .66), and hypertension (3/7, 43%, versus 13/20, 65%; P = .39) (Table 1 in the Online Supplemental Data).

ICU Clinical Data

Patients in the reduced-diffusivity group trended toward more frequent acute renal failure documented in the ICU clinical notes (7/7, 100%, versus 9/20, 45%; P = .06) and lower estimated glomerular filtration rate values (49 versus 85 mL/min, P = .06) at MR imaging (Table 2 in the Online Supplemental Data). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in the frequency of septic shock (6/7, 85.7%, versus 18/20, 90.0%), acute liver failure (1/7, 14.3%, versus 2/20, 10.0%), cardiac involvement (2/7, 28.6%, versus 2/20, 10.0%), ischemic bowel (1/7, 14.3%, versus 2/20, 10.0%), or other clinical and lab indices, including overt Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, as listed in table 2 of the Online Supplemental Data. The reduced-diffusivity group showed significantly depressed mean values of the lowest hemoglobin levels (8.1 versus 10.2 g/dL, P < .05), elevated serum sodium levels (147 versus 139 mmol/L, P = .04), and a trend toward elevated highest D-dimers (4080 versus 2386 ng/L, P = .09), all obtained within 24 hours before MR imaging. Other clinical variables, including SOFA scores at admission, sedatives, nitric oxide treatment, and ICU length of stay (up through the time of data collection), were not significantly different between the 2 groups (Table 1 in the Online Supplemental Data).

One patient in the reduced-diffusivity group and one in the control group underwent lumbar puncture for CSF analysis. The patient in the control group was diagnosed with CNS cryptococcosis in the setting of HIV and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection; the CSF sample from this patient showed 108 white blood cells and protein levels at 141 mg/dL. CSF samples from the patient in the reduced-diffusivity group were without pleocytosis (≤4 cells) and had mean protein levels of 152 mg/dL.

Imaging Findings

The extent of bilateral, supra- and infratentorial white matter abnormalities was significantly greater in the reduced-diffusivity group than in the control group (median Likert scores, 3, 2 versus 1, 0, respectively; P < .002). White matter lesions in the reduced-diffusivity group were also more likely than in controls to show an unusual, confluent pattern of supratentorial (P < .001) and middle cerebellar peduncular (6/7, 86%, versus 1/20, 5%; P < .001) involvement (Online Supplemental Data, Figs 2–4). Cerebellar white matter (P = .002) and brain stem (P = .04) lesions were significantly more common in the reduced-diffusivity group than in the control group, whereas white matter lesions trended toward a predominantly symmetric pattern in the reduced-diffusivity group (7/7, 100%, versus 11/19, 58%; P = .06). There was no significant difference between groups regarding U-fiber or corpus callosal involvement, percentage of patients with >10 microbleeds, cortical laminar necrosis, or abnormal deep gray matter signal changes (all P > .25), per Online Supplemental Data.

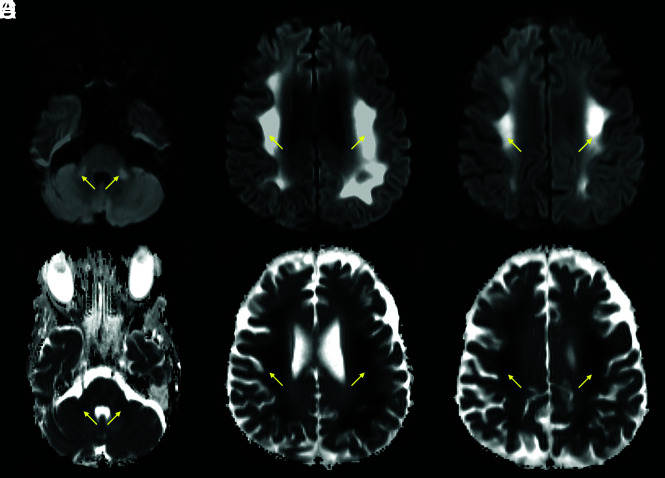

FIG 2.

A 64-year-old man with a history of diabetes and hyperlipidemia, admitted with COVID-19–related hypoxemic respiratory failure and worsening septic shock. Axial DWI (A–C) and ADC images (D–F) show extensive, bilateral, predominantly symmetric, DWI-hyperintense signal in the white matter of the bilateral middle cerebellar peduncles, corona radiata, and centrum semiovale, with corresponding dark signal intensity on the ADC images (yellow arrows), reflecting leukoencephalopathic changes with marked, confluent reduced diffusivity.

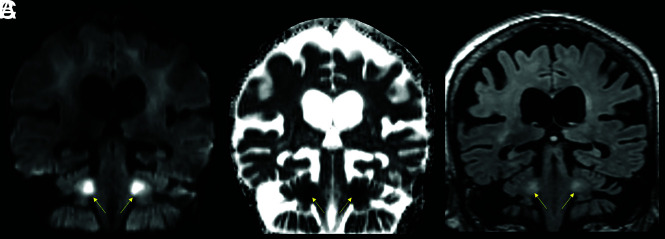

FIG 4.

A 76-year-old female patient with a history of schizoaffective disorder and Grave’s disease, admitted with COVID-19. Coronal DWI (A), ADC (B), and FLAIR (C) images. The brain MR images showed a leukoencephalopathy with restricted diffusion, predominantly affecting the middle cerebellar peduncles (yellow arrows) and adjacent cerebellar white matter.

Contrast was administered to 4/7 (57%) patients in the reduced-diffusivity group and 7/20 (35%) in the control group. One patient in each group had abnormal intraparenchymal enhancement (focal cortical enhancement in a region of laminar necrosis for a patient in the reduced-diffusivity group, and a small enhancing focus for a patient with cerebral cryptococcosis associated with HIV/SARS-CoV-2 co-infection in the control group). No definite abnormal leptomeningeal enhancement was present in any of our patients.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that in a consecutive cohort of adult patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the ICU requiring post-admission brain MR imaging, severe COVID-19 leukoencephalopathy with reduced diffusivity was associated with obesity, acute renal failure, mild hypernatremia, anemia, and an unusual, striking, and abnormal brain white matter lesion distribution pattern on MR imaging, featuring diffuse, confluent, predominantly symmetric supratentorial and middle cerebellar peduncular lesions. Although there were no significant differences in age, gender, race, or ethnicity between the reduced diffusivity and control groups, in both groups, older age (mean 63 years) and male sex (71–75%) were predominant.

Several articles to date have reported the occurrence of white matter signal abnormalities in patients with severe COVID-19.4,17-19 Kandemirli et al17 observed 3 (of 12) critically ill patients with subcortical or deep white matter lesions but without reduced diffusivity. More recently, Radmanesh et al4 described a series of patients with leukoencephalopathy, reduced diffusivity, and microhemorrhages. A systematic analysis of the risk factors and laboratory and clinical variables associated with this unusual leukoencephalopathy, however, has not previously been emphasized in the literature.3

We saw no significant differences between groups regarding the duration of subjective dyspnea before ICU admission, the lowest reported pulse oximetry before admission, PaO2/FiO2 ratios on admission, the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or worst arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) and lowest oxygen saturation during the first 24 hours in the ICU (Online Supplemental Data). These similarities in baseline oxygenation parameters were surprising, given that hypoxia has been hypothesized to be a major culprit in the pathophysiology of these white matter changes. Indeed, oxygenation indices (worst arterial PO2 and lowest O2 saturation oxygenation) on the day of MR imaging were lower in the control group, likely reflecting that 45% of those patients had been extubated by that time (versus 14% extubated in the reduced-diffusivity group, Online Supplemental Data).

Except for body mass index (BMI), our reduced-diffusivity and control groups were well-matched (Online Supplemental Data). The reduced-diffusivity group had a significantly higher mean BMI of 36 versus 28 in the control group (corresponding to “moderately obese” versus “overweight,” respectively). Although there is no established direct link between obesity and leukoencephalopathy, obesity is a known risk factor for insulin resistance, lacunar infarcts, and chronic small-vessel disease.20-22 The effect of obesity on arteriosclerosis might be a contributing factor to the increasingly recognized thrombotic microangiopathy and endotheliitis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.23 Lampe et al24 described visceral obesity being associated with a predominance of deep white matter (rather than periventricular) MR imaging abnormalities and suggested a potential role for interleukin 6 and other proinflammatory cytokines in the development of white matter pathology. The microangiopathic effect of obesity (with potential superimposed effects mediated by cytokines) might further compromise borderzone regions located in the deep cerebral white matter and middle cerebellar peduncles.25

Several clinical variables were different between our 2 cohorts, including a lower mean value for the lowest hemoglobin level within 24 hours before MR imaging (8.1 versus 10.2, P < .05), mildly higher mean values of the most elevated serum sodium at the same time point (147 versus 139, P < .04), and a trend toward more acute renal dysfunction (glomerular filtration rate = 49 versus 85 mL/min; P < .06) in the reduced-diffusivity group. Other organ system damage was not significantly different between groups, including cardiac events, acute liver failure, overt Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, ischemic bowel, and mean number of systems affected (Online Supplemental Data).

Although these differences may simply reflect an epiphenomenon, it is intriguing to speculate whether cytokine effects, which could also be related to obesity, might contribute to some of these abnormal lab indices. For example, interleukin 6 and other proinflammatory cytokines (eg, interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor-α) are known to have a central role in the anemia seen during systemic inflammatory processes, impacting iron homeostasis and the reticuloendothelial system as well as impairing regulatory feedback of iron absorption in the gastrointestinal tract.26,27 Interleukin 6 has been shown to mediate low iron levels during inflammatory states via the production of hepcidin.28 These cytokines might also modulate the transcription of the erythropoietin (EPO) gene and inhibit erythroid progenitor cells in the bone marrow.26

The modest hypernatremia at the time of MR imaging is more challenging to explain. Both groups had similar critical illness severity (reflected by SOFA scores of 9.3 and 7, respectively; P = .09) and had no reported differences in water intake or extrarenal water losses (gastrointestinal- or skin-mediated). Although this finding might reflect hypothalamic involvement with impaired water homeostasis, renal dysfunction in COVID-19 has more often been reported to result in hyponatremia.29,30

The pattern of MR imaging signal abnormalities we observed is striking. This pattern of diffuse, confluent, predominantly symmetric supra- and infratentorial involvment with middle cerebellar peduncle lesions (seen in 6/7 cases, 86%) is unusual and noteworthy. The neuroanatomic distribution of these abnormalities appears more selective than those reported in cases of delayed posthypoxic leukoencephalopathy at our institution and in the literature. Delayed posthypoxic encephalopathy is often more extensive, with subcortical white matter involvement and less frequent infratentorial involvement.7,31 None of the patients in our reduced-diffusivity group had a history of recent cardiac arrest, though 1 patient in the control group had an episode of cardiac arrest without developing these findings.

There have been multiple reports of white matter abnormalities associated with sepsis and critical illness. Sharshar et al12 described white matter lesions in 5/9 (55%) patients with septic shock and clinical brain dysfunction (mean SOFA, 8). Polito et al11 published a similar study of 71 patients with septic shock and noted 15 patients (21%) with leukoencephalopathy (median highest SOFA score, 9). These authors suggested that the leukoencephalopathy seen with septic shock may be related to an altered blood-brain barrier, allowing passage of proinflammatory molecules and neurotoxins.11

Another possibility in the imaging-based differential diagnosis of the unusual pattern of leukoencephalopathy in these patients is a metabolic or toxic etiology.32,33 There were no differences between the reduced-diffusivity and control groups regarding sedatives, the use of opioid medications, nitric oxide, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment. The possibility of a metabolic etiology is intriguing because the anatomic distribution of white matter lesions in our patients overlaps the pattern seen with a genetic chloride channelopathy (chloride voltage-gated channel 2 [CLCN2]–related leukoencephalopathy).34,35 It has been established, however, that the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor used by the SARS-CoV-2 virus has a chloride-binding site and is regulated by this electrolyte.36 There is also some degree of overlap between the angiotensin II and chloride channel pathways physiologically, with angiotensin II producing activation of chloride currents in cerebral vessels.37,38 A direct connection between COVID-19 and specific ion-transport abnormalities, however, has not been reported to date.

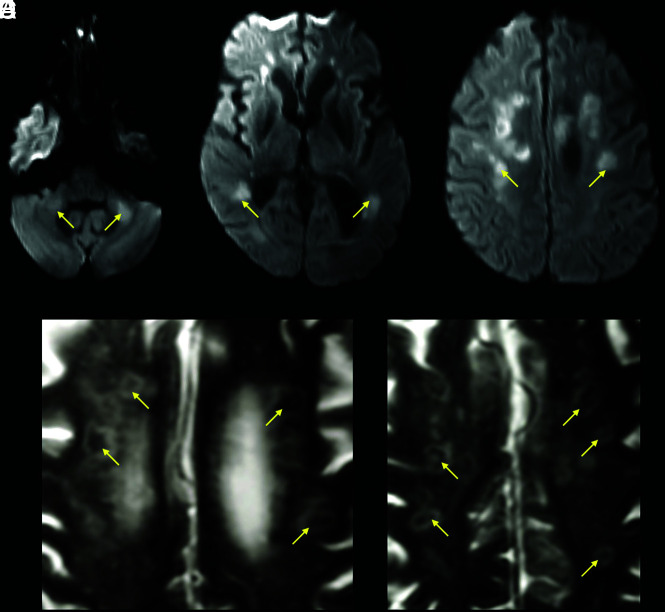

One of our patients showed cavitary, necrotic-appearing lesions in regions with reduced diffusivity, suggestive of the MR imaging findings that accompany multifocal necrotizing leukoencephalopathy (Fig 3).39 The anatomic distribution of these lesions resembled that of our other patients with leukoencephalopathy with reduced diffusivity; hence, this appearance may reflect a more advanced stage of white matter cellular injury, as was described in some early case reports of COVID-19–associated acute necrotizing encephalopathy.39,40

FIG 3.

A 63-year-old male patient with a history of diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and obstructive sleep apnea admitted with COVID-19–related hypoxic respiratory failure due to acute respiratory distress syndrome. DWI (A–C) shows bilateral areas of reduced diffusivity, involving the body of the corpus callosum, middle cerebellar peduncles, and periventricular white matter (arrows, ADC not shown). Magnified axial T2-weighted MR images (D and E) show a peculiar cavitary appearance of some of the lesions, with decreased signal centrally and a peripheral T2-hyperintense rim (yellow arrows). These lesions were interpreted as areas of early cavitation within the white matter abnormalities. A follow-up MR imaging (not shown) showed resolution of the restricted diffusion within these lesions but with progression of the cavitary/necrotic changes.

This observational study has several limitations, including a small sample size, which could be affecting the potential effect of some clinical variables. The patients included in the study may reflect a proportion of those with severe COVID-19 in the ICU who were stable enough to have a brain MR imaging, potentially biasing this analysis. The development of cavitary changes in only one of the patients in the group with restricted diffusion could be related to a more advanced stage of white matter injury, but this is difficult to confirm with the small number of cases included in the study. Nevertheless, we observed several significant correlations among the imaging, clinical, and laboratory findings, providing a basis for future hypothesis testing in larger cohorts. Different field strengths and susceptibility sequences in different MR imaging scanners limit comparison of the prevalence of microhemorrhages between cohorts. Lack of prior imaging in several patients limits assessment of pre-existing or other pathologies. Finally, the retrospective design also limits the availability of oxygenation data during ICU admission, which may have provided a more precise measure of the cumulative burden of hypoxia experienced by each patient.

CONCLUSIONS

The unusual pattern of white matter injury we observed, together with the clinical and laboratory correlates, overlaps that of several conditions that may help elucidate the pathophysiology of severe COVID-19 encephalopathy. These include but are not limited to delayed posthypoxic leukoencephalopathy, sepsis-related leukoencephalopathy, and metabolic encephalopathies related to electrolyte disturbances. The anatomic distribution and presence of reduced diffusivity within these white matter lesions suggest a combination of several potential factors, including thrombotic microangiopathy, underlying microvascular changes related to electrolyte transport derangements that result in borderzone oligemia, potentially direct viral injury,41 and silent hypoxia5,16 in the context of the well-known cytokine storm seen in many critical patients with COVID-19.14,15

ABBREVIATIONS:

- BMI

body mass index

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- ICU

intensive care unit

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

Footnotes

Disclosures: Otto Rapalino—UNRELATED: Travel/Accommodations/Meeting Expenses Unrelated to Activities Listed: GE Healthcare, Comments: travel expenses to GE Healthcare–sponsored meeting August 2019. Brian L. Edlow—RELATED: Grants: James S. McDonnell Foundation COVID-19 Recovery of Consciousness Consortium. Susie Huang—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: Siemens, Comments: research grant for clinical translation of fast neuroimaging sequences*; Payment for Lectures Including Service on Speakers Bureaus: Siemens, Comments: speaker engagement at Organization for Human Brain Mapping Annual Meeting. Brandon Westover—RELATED: Grant: National Institutes of Health*; UNRELATED: Employment: Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School; Grants/Grants Pending: National Institutes of Health.* Rajiv Gupta—UNRELATED: Consultancy: Idorsia, Facebook, Medtronic, Siemens; Expert Testimony: Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Penn State; Grants/Grants Pending: National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense; Payment for Lectures Including Service on Speakers Bureaus: Siemens. Shibani Mukerji—RELATED: Grant: National Institute of Mental Health, Comments: K23MH115812.* Michael H. Lev—UNRELATED: Consultancy: Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, GE Healthcare; Grants/Grants Pending: GE Healthcare, National Institutes of Health.* *Money paid to the institution.

References

- 1.Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2268–70 10.1056/NEJMc2008597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pleasure SJ, Green AJ, Josephson SA. The spectrum of neurologic disease in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic infection: neurologists move to the frontlines. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:679 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuki K, Fujiogi M, Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. Clin Immunol 2020;215:108427 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radmanesh A, Derman A, Lui YW, et al. COVID-19-associated diffuse leukoencephalopathy and microhemorrhages. Radiology 2020;297:E223–27 10.1148/radiol.2020202040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couzin-Frankel J. The mystery of the pandemic’s “happy hypoxia.” Science 2020;368:455–56 10.1126/science.368.6490.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balan S, Gupta K, Balasundaram P, et al. Reversible hypoxic brain injury: the penumbra conundrum of Grinker. BMJ Case Rep 2019;12:e228670 10.1136/bcr-2018-228670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beeskow AB, Oberstadt M, Saur D, et al. Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy (DPHL): an uncommon variant of hypoxic brain damage in adults. Front Neurol 2018;9:708 10.3389/fneur.2018.00708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breit H, Jhaveri M, John S. Concomitant delayed posthypoxic leukoencephalopathy and critical illness microbleeds. Neurol Clin Pract 2018;8:e31–33 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamora CA, Nauen D, Hynecek R, et al. Delayed posthypoxic leukoencephalopathy: a case series and review of the literature. Brain Behav 2015;5:e00364 10.1002/brb3.364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garofalo AM, Lorente-Ros M, Goncalvez G, et al. Histopathological changes of organ dysfunction in sepsis. Intensive Care Med Exp 2019;7:45 10.1186/s40635-019-0236-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polito A, Eischwald F, Maho AL, et al. Pattern of brain injury in the acute setting of human septic shock. Crit Care 2013;17:R204 10.1186/cc12899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharshar T, Carlier R, Bernard F, et al. Brain lesions in septic shock: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:798–806 10.1007/s00134-007-0598-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shindo A, Suzuki K, Iwashita Y, et al. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy with multiple microbleeds in cerebral white matter. Am J Med 2018;131:e297–98 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. ; HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020;395:1033–34 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore BJ, June CH. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science 2020;368:473–74 10.1126/science.abb8925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon IH, Normandin E, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Neuropathological features of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;383:989–92 10.1056/NEJMc2019373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kandemirli SG, Dogan L, Sarikaya ZT, et al. Brain MRI findings in patients in the intensive care unit with COVID-19 infection. Radiology 2020;297:E232–35 10.1148/radiol.2020201697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sachs JR, Gibbs KW, Swor DE, et al. COVID-19-associated leukoencephalopathy. Radiology 2020;296:E184–85 10.1148/radiol.2020201753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang M, Buch K, Li MD, et al. Leukoencephalopathy associated with severe COVID-19 infection: sequela of hypoxemia? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020;41:1641–45 10.3174/ajnr.A6671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dearborn JL, Schneider AL, Sharrett AR, et al. Obesity, insulin resistance, and incident small vessel disease on magnetic resonance imaging: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Stroke 2015;46:3131–36 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakim AM. Small vessel disease. Front Neurol 2019;10:1020 10.3389/fneur.2019.01020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ter Telgte A, Wiegertjes K, Gesierich B, et al. Contribution of acute infarcts to cerebral small vessel disease progression. Ann Neurol 2019;86:582–92 10.1002/ana.25556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 2020;395:1417–18 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lampe L, Zhang R, Beyer F, et al. Visceral obesity relates to deep white matter hyperintensities via inflammation. Ann Neurol 2019;85:194–203 10.1002/ana.25396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kataoka H, Izumi T, Kinoshita S, et al. Infarction limited to both middle cerebellar peduncles. J Neuroimaging 2011;21:e171–72 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2010.00503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayden SJ, Albert TJ, Watkins TR, et al. Anemia in critical illness: insights into etiology, consequences, and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:1049–57 10.1164/rccm.201110-1915CI [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houston DS. Hepcidin and the anemia of critical illness. Crit Care Med 2018;46:1030–31 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemeth E, Rivera S, Gabayan V, et al. IL-6 mediates hypoferremia of inflammation by inducing the synthesis of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin. J Clin Invest 2004;113:1271–76 10.1172/JCI200420945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lippi G, South AM, Henry BM. Electrolyte imbalances in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Ann Clin Biochem 2020;57:262–65 10.1177/0004563220922255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puelles VG, Lutgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med 2020;383:590–92 10.1056/NEJMc2011400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer MA. Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy: case report with a review of disease pathophysiology. Neurol Int 2013;5:e13 10.4081/ni.2013.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Oliveira AM, Paulino MV, Vieira AP, et al. Imaging patterns of toxic and metabolic brain disorders. Radiographics 2019;39:1672–95 10.1148/rg.2019190016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sener RN. Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging patterns in metabolic and toxic brain disorders. Acta Radiol 2004;45:561–70 10.1080/02841850410006128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaitan-Penas H, Apaja PM, Arnedo T, et al. Leukoencephalopathy-causing CLCN2 mutations are associated with impaired Cl(-) channel function and trafficking. J Physiol 2017;595:6993–7008 10.1113/JP275087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Z, Lu T, Peng L, et al. CLCN2-related leukoencephalopathy: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Neurol 2019;19:156 10.1186/s12883-019-1390-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rushworth CA, Guy JL, Turner AJ. Residues affecting the chloride regulation and substrate selectivity of the angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACE and ACE2) identified by site-directed mutagenesis. FEBS J 2008;275:6033–42 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06733.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li RS, Wang Y, Chen HS, et al. TMEM16A contributes to angiotensin II-induced cerebral vasoconstriction via the RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep 2016;13:3691–99 10.3892/mmr.2016.4979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson MT, Conway MA, Knot HJ, et al. Chloride channel blockers inhibit myogenic tone in rat cerebral arteries. J Physiol 1997;502:259–64 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.259bk.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Premji S, Kang L, Rojiani MV, et al. Multifocal necrotizing leukoencephalopathy: expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2019;78:340–47 10.1093/jnen/nlz003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, et al. COVID-19-associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: imaging features. Radiology 2020;296:E119–20 10.1148/radiol.2020201187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paniz-Mondolfi A, Bryce C, Grimes Z, et al. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). J Med Virol 2020;92:699–702 10.1002/jmv.25915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]