Abstract

This paper explores the epidemiological evidence about oral health of individuals with neurodegenerative conditions of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and dementia. PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched to identify the relevant research papers published during January 2012 to June 2020. All cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies reporting oral and dental morbid conditions for status and association with AD and dementia were explored. The explored literature from 22 studies shows that oral health parameters of oral health and levels of oral inflammatory markers were deranged and exaggerated in patients suffering from AD and dementia. Many studies have observed poor oral hygiene as result of lack or irregularity in toothbrushing. Regarding decayed, missing, and filled teeth status in AD/dementia populations, no significant difference is reported. Periodontal diseases have been noted at raised levels in AD and dementia patients and shown progression with aggravation in neurological disorders. Both edentulousness and low chewing efficacies are associated with low cognition. Stomatitis and coated tongue and other oral pathologies are significantly higher in AD patients. AD patients have demonstrated higher bacterial load and inflammation levels than controls, and consequently, inflammatory biomarker levels are also raised. AD patients have reduced salivary secretions and with low buffering capacity. Evidence from the current literature update postulates that individuals suffering from AD and dementia have special oral health-care needs. Appropriate oral health management may thus significantly improve their oral health-related and general quality of life.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, dementia, epidemiology, oral diseases

INTRODUCTION

Dementia, a form of acquired progressive cognitive impairment, significantly affects the daily activities of many individuals. It is the main cause of disability, dependence, and mortality, especially in the aging. It is most prevalent in elderly individuals worldwide, and 5%–7% of 60 years or older are affected by it.[1]

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, is becoming an important health concern.[2] Crudely, 6.08 million people in the United States have suffered from AD in 2017, and this astronomical figure is further projected to 15 million by 2060.[3] AD is an irreversible and progressive neurodegenerative condition characterized by the cardinal features of neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques. This results in severe neurodegeneration along with the synaptic and neuronal loss, which ultimately leads to neuronal atrophy.[4] Salient inflammatory features of AD include microglial stimulation and increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines in the affected regions.[5,6]

Oral health has been recognized as an essential component of overall well-being, with increasing demand in older communities. Oral hygiene, dentition, periodontal tissues, mucosal lesions, prosthesis and chewing capability, salivary secretions, and oral microbiology form essential components of oral health. Cognitive impairment is often followed by oral health deterioration.[7] Recent evidence suggests a significant association between cognitive decline and chronic periodontitis in dementia people. This is thought to be mediated through the common components of systemic inflammation in both the conditions.[8]

Current research reveals a uni- or bidirectional association between oral health and neurological degenerative conditions. The purpose of this narrative review paper is to explore the observational studies reporting status and impact of oral health conditions on patients with dementia and AD. There is growing interest to identify the factors that may explain the plausible link between oral conditions and neurological degenerative conditions. This review presents a summary and analysis on prevalence of oral conditions among AD and dementia patients and highlights the associated risk factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

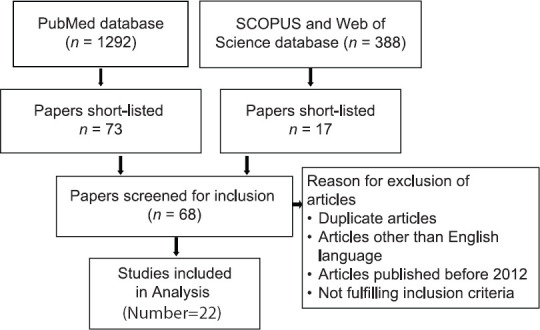

Databases of PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science from January 2012 to June 2020 were searched for this paper. Keywords of “Alzheimer's disease,” and “dementia,” with “oral hygiene,” “tooth loss,” “periodontitis,” “oral diseases,” “oral inflammation,” “oral infections,” and “chewing capacity” were used in different combinations, utilizing Boolean operators. Relevant titles, abstracts, and full-length papers published or accepted for publication during the period mentioned above were scrutinized for this review. Inclusion criteria were (a) the studies published from January 2011 to June 2020, (b) full text, (c) English, (d) having any of the “keywords,” and (e) open access. All cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies which explored the status of different oral health conditions with AD and dementia were included in the study and analyzed. Studies not fulfilling the inclusion criteria and not available on “open access” were excluded. Two authors (SAH and SA) searched the databases and collected relevant studies that were later scrutinized and data extracted by authors SAH and SAHB. A list of databases and literature searched is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data Extraction Flow Diagram

The extracted data included (1) study design and (2) participants' age and gender, baseline outcome measures of oral hygiene, dentition, dental caries, periodontal health, oral pathologies, inflammatory biomarkers, prosthesis, and masticatory functions.

RESULTS

Twenty-two observational studies were selected for review and are listed retrospectively from June 2020 to January 2012 [Table 1]. Five case–control, 12 cross-sectional, and 5 cohort studies were analyzed with the following oral health conditions.

Table 1.

Details of the selected studies exploring the association between oral health, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease

| Author’ name | Study type | Study sample | Participant’s age (in years) | Conditions observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gao et al.,[13] 2020 | Cross-sectional study |

n=228 Males=48, females=180, cases=129, controls=99 |

Mean age 80.2 | Dementia, DMFT, periodontal disease, oral hygiene |

| Lee et al.,[24] 2019 | Cross-sectional study |

n=57,277 Males=22,189, females=35,088 |

Age: □65 | Dementia, oral health, periodontitis, prosthesis |

| Yoo et al.,[18] 2019 | Cohort study |

n=209,806 Males=80, females=143, cases=104,903, controls=104,903 |

Median age Cases=68.5 Controls=66.5 |

Dementia, tooth loss |

| Alessandro et al.,[17] 2018 | Cross-sectional comparative study |

n=223 Males=80, females=143, cases=120, controls=103 |

Mean age Cases=79.1 Controls=77.68 |

Alzheimer’s disease, tooth loss, DMFT, periodontal disease |

| Ranjan et al.,[16] 2018 | Cross-sectional study |

n=300 Males=185, females=115 |

50-80 | Dementia, tooth loss |

| Holmer et al.,[9] 2018 | Case-control study |

n=230 Males=105, females=125, cases=154, controls=76 |

Median age Cases=70 Controls=67 |

Periodontitis, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment |

| Aragón et al.,[8] 2018 | Case-control study |

n=106 70 AD patients, 36 controls, females=54% |

Mean age AD cases 77.4±10.6, controls=62.6±7.1 | Alzheimer’s disease, oral health, tooth loss, dental caries, periodontal disease, saliva |

| Maurer et al.,[28] 2018 | Cross-sectional study |

n=20 Males=15, females=5 |

Age≥55 | Dental health, AD |

| Sochocka et al.,[30] 2017 | Cross-sectional study |

n=128 Males=45, females=83 |

Age range 55-90, median age70 | Cognitive impairment, periodontal disease, dementia, systemic inflammation, cytokines, AD |

| Chen et al.,[21] 2017 | Retrospective cohort study |

n=27963 Males=14,844, females=13,119 |

Age 50-70 | Chronic periodontitis, AD |

| Campos et al.,[26] 2017 | Case-control study |

n=16 Cases=11, controls=5 |

Mean age 76.7±6.3 | Full or partial edentulousness, chewing disability, cognitive function |

| Cestari et al.,[11] 2016 | Case-control study |

n=65 Males=28, female=42 (25 with AD, 19 with MCI, and 21 controls) |

Mean age 75.33±5.75 | AD, IL-6, inflammation, mild cognitive impairment, oral infection, periodontitis |

| Ide et al.,[20] 2016 | Cohort study | n=59 | Mean age 77.7±8.6 | Number of teeth, dental plaque, periodontitis, cognitive function, AD, inflammatory biomarkers |

| Chu et al.,[12] 2015 | Case-control study | n=118 (59 with dementia and 59 control) | Mean age 79.8±7.4 | Oral health, dementia toothbrushing habits, unstimulated salivary flow rates |

| Elsig et al.,[19] 2015 | Cross-sectional study |

n=51 Males=12, females=39 |

Mean age 82.5 | Chewing efficiency, tooth loss, cognitive impairment, dementia |

| Okamoto et al.,[15] 2017 | Cohort study | n=2335 | Mean age 71 | Tooth loss, mild memory impairment |

| Martande et al.,[10] 2014 | Cross-sectional study |

n=118 Males=52, female=66 |

Mean age 65.2±7.3 | AD, dementia, chronic periodontitis, oral health |

| Naorungroj et al.,[25] 2013 | Cross-sectional study | n=5942 | Age range 45-65 | Oral health measures, cognitive function |

| Cicciù et al.,[23] 2013 | Cross-sectional study |

n=158 with AD male=57, female=101 |

Age range 65-87 | AD, DMFT, periodontal disease, OHIP-14 |

| Kamer et al.,[22] 2012 | Cross-sectional study | n=38 | Age 70 | Periodontal inflammation, AD, tooth loss |

| Sparks Stein et al.,[29] 2012 | Cohort study |

n=158 Males=75, female=83 |

Mean age 70 | AD, antibodies, periodontal bacteria; periodontal disease; mild cognitive impairment |

| Ribeiro et al.,[14] 2012 | Cross-sectional study | n=60 | Mean age 79.13±5.59 | AD, GOHAI index, DMFT, OHI index, prosthesis |

DMFT-Decayed, missing, and filled teeth; GOHAI-General Oral Health Assessment Index; OHI-Oral hygiene index; AD-Alzheimer’s disease; OHIP-Oral health impact profile; MCI-Mildly cognitively impaired; IL-6-Interleukin-6; n-number of study sample

Individual oral health outcome measures

Oral hygiene status and habits

A recent study has reported poor oral hygiene (72.2% vs. 43.1%, P < 0.001), no usage of dental floss (69.4% vs. 96.9%, P < 0.001), and infrequent visits to dentist (33.3% vs. 58.3%, P = 0.01) in Alzheimer patients.[8] Another recent study reported that oral hygiene practices, such as regular toothbrushing frequency, were less prevalent in patients with neurodegenerative diseases compared to controls (82.4% vs. 90.8%, P = 0.226).[9] A study by Martande et al. reported that a mean proportion of bleeding on probing (BOP) sites were much greater in AD patients as compared to nondementia (ND) patients (P < 0.01). It also documented a nonsignificant difference in the poor oral hygiene status of individuals with AD and controls (69% vs. 57%, P > 0.05).[10] Similarly, Cestari et al.[11] also reported higher plaque index (PI) scores in AD patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and the control group (71.87 ± 26.58%, 67.69 ± 28.41%, and 58.47 ± 26.52%, respectively, P = 0.357). Chu et al. found that lesser people with dementia brush their teeth twice a day, as compared to controls (5% vs. 31%, P < 0.001).[12] Gao et al.[13] have shown significantly (P = 0.027) higher level of visible plaque in 77% of dementia patients, 57% patients reported difficulties in toothbrushing, and 36% have visited a dentist.

Dentition and dental caries status

Ribeiro et al.[14] reported that AD patients had a significantly fewer number of natural teeth (P = 0.0004) and higher decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT) scores (P = 0.0002) than the non-AD controls. Another study also found more missing teeth (P = 0.03) and a longer duration of edentulism (P = 0.03) in AD and MCI patients compared to the control population. Although, in terms of DMFT scores, an insignificant difference was detected between AD and controls (P = 0.26).[11] Two studies have reported a significant link between DMFT scores, tooth loss, and AD. Of these, the first study reported that matched non-AD had a significantly lesser percentage of nondecayed teeth in comparison with AD population (81.7% vs. 93.4%, P = 0.02, respectively).[9] The other study also reported a significant differences between the controls and AD patients regarding DMFT scores (25.0 ± 7.7 vs. 16.5 ± 7.0, P < 0.01, respectively), number of filled teeth (2.2 ± 3.4 vs. 6.6 ± 5.6, P < 0.01, respectively), and number of sound teeth (21.0 ± 10.4 vs. 8.3 ± 6.5, P < 0.01, respectively).[8] Another study postulated that a lesser number of teeth were associated with mild memory impairment (MMI) risk (P < 0.05) and each loss of tooth predicted the development of MMI significantly (P = 0.01).[15] In another study,[16] the number of teeth was found to be directly associated with MMSE score in dementia patients. The study also showed that age, SES, education, and marital status had a significant impact on dementia scale. Alessandro et al.[17] reported statistically higher values of decayed teeth (P = 0.005) and tooth loss with less filling in AD patients as compared to controls. A recent large cohort study[18] conducted over a 10-year period has shown a significant relationship between dementia incidence and number of missing teeth; odds ratios were higher in women than men (P < 0.001), urban than rural (P < 0.001), and most higher for age group ≥80 years (odds ratio [OR]: 2.38, confidence interval [CI]: 2.216–2.553, P < 0.001). Gao et al.[13] have shown higher dental caries (P = 0.041) in dementia cases, and the mean difference in DMFT was 3 ± 8 between people with and without dementia.

Contrary to the above evidence, some studies found an insignificant difference in terms of DMFT parameters and number of sound teeth between AD/dementia population and healthy individuals (controls). Elsig et al. testified that although a higher number of teeth were missing in dementia patients than controls, the difference was statistically nonsignificant (P = 0.53).[19] Adding to these conflicting findings, another study found similar DMFT scores in both the dementia and control groups (22.3 ± 8.2 vs. 21.5 ± 8.2, P = 0.59).[12] In addition, some studies also showed an insignificant difference between the number of teeth present in ND patients and AD patients (15.8 ± 3.6 vs. 16.2 ± 4.2, P > 0.05), respectively.[10]An insignificant association between the teeth number and a decline in standardized Minimal-Mental State Examination (sMMSE) score was noted at baseline (P = 0.4).[20]

Periodontal health

It was observed that AD patients had higher and significant values of periodontal disease markers (measured by gingival index [GI], periodontal index [PI], pocket probing depth [PPD], and clinical attachment loss [CAL]) as compared to the controls and the condition deteriorated as the disease advanced from mild to severe. The mean value of BOP sites was higher in AD patients than the non-AD (P < 0.01).[10] In a recent study, generalized marginal alveolar bone loss was associated with the AD group (9.2% vs. 2.6%, OR = 5.81: 95% CI: 1.14–29.68) and deep periodontal pockets (≥6 mm) with higher number of teeth (56.2% vs. 17.1%, OR = 8.43: 95% CI: 4.00–17.76) compared to non-AD controls.[9] In another matched case–control study, patients who were exposed to chronic periodontitis for 10 years verified an advanced risk for developing AD as compared to unexposed individuals (hazard ratio: 1.707, P = 0.007).[21] Danish older adults who had periodontal inflammation were found significantly with lower cognitive function test scores in comparison to those who were without periodontal inflammation.[22] A study by Cicciù et al. found that periodontitis and fewer number of teeth are the two important factors impacting the quality of life in terms of oral health in AD patients.[23] Alessandro et al. reported statistically higher values of periodontal disease measured by chronic periodontal inflammation (CPI) (P < 0.001) and GI (P < 0.001) in AD patients as compared to controls.[17] Gao et al.[13] have shown 64% of dementia patients with periodontal pockets, 98% had gingival bleeding, however, the difference in periodontal parameters of gingival bleeding, periodontal pocket, and loss of attachment was nonsignificant between dementia and nondementia patients.

Contrary to the results presented earlier, a study by Chu et al. found an insignificant difference in the prevalence of periodontal pockets (CPI score ≥3) between the two groups (78% vs. 74%, P = 0.64).[12] Similarly no significant differences were noted in periodontal health of patients with AD compared to controls in another study.[11] Periodontitis was less common in dementia patients in a large population-based recent study.[24]

Prosthesis status and masticatory function

More AD patients were using dentures in comparison to the non-AD group (65.2% vs. 58.3%, P < 0.05) as reported in a study.[8] Naorungroj et al. also revealed that edentulousness was linked with lower cognitive status. Furthermore, this study reported that tooth loss was an important marker of poorer executive function among edentulous patients.[25] A case–control study by Campos et al.[26] discovered that the association between masticatory function reported through chewing efficacy and cognitive status was impaired in mild AD in the elderly, indicating a harmful effect of the disease on mastication. Another study reported the chewing efficiency to be worse in dementia patients than in the controls (P < 0.011).[19] Edentulism was found high in AD patients than non-AD in a study by Alessandro et al.[17] Poor masticatory ability was associated with accelerated cognitive decline but not with dementia.[27] Dementia was more common in individuals with removable dentures as observed in a large population-based study by Lee et al.[24]

Oral pathologies

In AD patients, candidiasis (11.8% vs. 0.0%, P = 0.048) and cheilitis (15.9 vs. 0.0%, P = 0.015) were found significantly higher as compared to the controls.[8] There was an higher and significant prevalence of candidiasis (32% vs. 9.5%, P = 0.050) and coated tongue (72% vs. 19.0%, P < 0.001) in AD patients compared to controls.[11] A significant association (P = 0.0062) between AD patients and oral lesion (prosthetic stomatitis) was most commonly observed with a prevalence of 60%.[14]

Salivary status and buffering effect

In AD patients, the unstimulated (1.0 ± 1.3 vs. 1.5 ± 1.1) and stimulated salivary flow (3.0 ± 3.0 vs. 5.2 ± 3.2) rates per minute were comparatively lower, and the basal saliva was more acidic (7.4 ± 0.4 vs. 7.0 ± 0.8) with a lower buffering capacity (46% vs. 80%).[8] Chu et al. reported that the unstimulated salivary flow rate in AD patients was lower in comparison to the control group (0.30 vs. 0.41 ml/min, P = 0.043).[12]

Oral pathogens

AD patients have demonstrated more bacterial load and inflammation than controls. Bacterial species, mainly involved in developing caries, were higher in percentage (between 76% and 93%) in AD patients as compared to non-AD individuals (67%–86%).[28] Pamela Sparks Stein et al.[29] observed that the baseline levels of antibodies of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Prevotella intermedia were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the AD patients as compared to healthy controls. A rise in antibody levels in response to periodontal bacteria in AD patients, years before cognitive impairment, may suggest that PD may contribute to the risk of AD onset or progression. However, another study reported no significant association between baseline serum Porphyromonas gingivalis antibody levels and the rate of decline on the AD Assessment Scale score (P = 0.90) or a decline in the sMMSE score (P = 0.10).[20]

Inflammatory markers

AD patients showed significantly raised interleukin (IL)-6 levels compared with controls (P = 0.029), and periodontitis patients were with noticeably higher tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) levels than AD patients with healthy periodontium (P = 0.005). TNF-α concentrations were correlated positively with the periodontal indices, including PPD, CAL, BI (P < 0.001), and PI (P = 0.008). This meant that patients with poor periodontal status had higher serum TNF-α levels. IL-6 and TNF-α were also positively correlated in the observed groups (P < 0.001).[11] Antibody levels in response to F. nucleatum and P. intermedia were significantly (P = 0.05) raised in serum of AD patients compared with controls at baseline.[29] Another study showed an insignificant relationship between systemic inflammatory markers, dental measures, and cognition.[20] During the disease status, neuropsychiatric symptoms and neurodegenerative changes modify, in the presence of other sources of pro-inflammatory mediators, exacerbate systemic inflammation and may deepen the neurodegenerative lesions.[30]

DISCUSSION

Dementia has emerged as a major health concern and is mostly associated with AD.[31] The preservation of a functional stomatognathic system is an important goal in the management of patients in general, and AD patients in particular, to maintain functions, such as chewing, speech, and esthetics in order to improve the quality of life of patients.[17]

This review of studies demonstrates that people suffering from neurodegenerative diseases of AD and dementia are more prone to poor oral health conditions related to oral hygiene, dentition status, periodontal disease, and masticatory problems. In addition, neurodegenerative disease patients also suffer more from oral lesions, reduced salivary flow, and halitosis compared to healthy individuals. Results from studies show that dental caries and periodontal disease are related to the degree of severity of AD.[24]

Kamer et al.[22] observed impaired cognition in patients with CPI compared to without CPI. In patients with CPI, many missing teeth had higher cognition impairment in comparison to those with less missing teeth. In AD patients, a significant deterioration of periodontal health and a positive association of periodontal disease progression with the degree of cognitive function impairment are observed in a study.[10] This finding may point toward a common paradigm of inflammation representing the clinical overlap between neurodegeneration and chronic oral inflammation. However, descriptive studies and only statistical associations do not warrant a causal relationship. Knowledge about the oral health of geriatric patients with neurodegenerative diseases and oral diseases is warranted. For the current review, we were able to trace 22 studies during the last 9 years that have reported status and associations between oral health and neurodegenerative conditions of dementia and AD.

Most of the studies discussed in this review have revealed a significant association between dementia and AD and poor oral health. In the elderly with dementia and AD, literature reports an increased risk of poor oral health and decreased oral hygiene.[24,25,32] Studies also report significant and proportional relationships between severe dementia and worse dental health.[9,17] A recent longitudinal study by Ide et al.[20] observed that CPI and tooth loss might precede the development of AD. One possible reason for poor oral health in patients with dementia and cognitive impairment could be declining motor skills required in maintaining oral health appliances.[33] A correlation between lower cognitive status and edentulism, complete tooth loss, and a less number of teeth was also reported in a study.[25] A case–control study revealed that patients with AD and cognitive impairment reported poor overall oral health status and more marginal alveolar bone loss compared to cognitively healthy controls.[9]

Regarding oral health parameters besides CPI, a multicenter study by Aragon et al.[8] reports worse oral hygiene, higher use of removable prostheses, higher incidence of candida infection, cheilitis, lower salivary flow, and lower buffering capacity among AD population compared to healthy controls. Moreover, in AD patients, a significant association is found between cognitive impairment and masticatory function.[11] In addition, chewing efficiency is worse and seems strongly associated with cognitive impairment.[19] This evidence, although novel, reiterates that neurodegeneration has significant deleterious effects on the oral health of individuals. These effects, from the preliminary evidence, seem to affect every facet of the orodental morbidity.

Recent evidence also points toward biological links between neurodegeneration and oral disease. Findings about the elevated levels of IL-6 in AD patients and its association with high TNF-α levels in patients with CPI propose that immunoinflammatory mechanisms of periodontitis may have some roles in the exacerbation of AD.[11] Another study reported the commonality of microbes such as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum, in AD and CPI patients. These pathogens were found in infected molars of AD patients.[28] Sochocka et al.[30] postulated that release of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, during periodontal disease, could cause chronic periodontitis and possibly contribute to the clinical onset of AD. Another study observed a link between periodontal disease and the magnitude of brain amyloid accumulation, suggesting that periodontal inflammation/infection may increase the risk for amyloid deposition in the brain.[22] Independent of baseline cognitive state, periodontitis may increase cognitive decline in AD patients.[12]

Currently, the association between oral health and cognitive function lacks causal directions.[25] Accordingly, early identification of oral diseases and subsequent preclinical treatment of chronic oral conditions, especially in the elderly, may slow the progression of many debilitating neurodegenerative diseases.[34] Finally, a modification of risk factors, such as by correcting behaviors and lifestyle related to oral health, and early treatment can help older people improve general health.

CONCLUSIONS

Although still preliminary, current evidence suggests that older people with neurodegeneration have worse orodental health status. The likely reasons for this association range from increasing difficulties with oral health self-care to inflammatory mechanisms. Further research is warranted to identify and establish the factors that deteriorate oral condition in dementia and AZ.

Limitations of study

This literature update has been limited to observational studies. Limited range of outcome measures, different study designs, methodological heterogeneity, variability in diagnostic criteria for dementia, AZ and oral health parameters are the limitations that were noted in the studies extracted for this review. Therefore, the temporality for the observed associations is unclear.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:63–7500. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wortmann M. World Alzheimer report 2014: Dementia and risk reduction. Alzheimer's Dement. 2015;11:P837. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N, Kawas CH, Corrada MM. Forecasting the prevalence of preclinical and clinical Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pesini P, Pérez-Grijalba V, Monleón I, Boada M, Tárraga L, Martínez-Lage P, et al. Reliable measurements of the ß -amyloid pool in blood could help in the early diagnosis of AD. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/604141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaur S, Agnihotri R. Alzheimer's disease and chronic periodontitis: Is there an association? Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:391–404. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes C, Cotterell D. Role of infection in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: Implications for treatment. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:993–1002. doi: 10.2165/11310910-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan LJ, Strauss J. Cognitive impairment in older adults and oral health considerations: Treatment and management. Dent Clin North Am. 2014;58:815–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aragón F, Zea-Sevilla MA, Montero J, Sancho P, Corral R, Tejedor C, et al. Oral health in Alzheimer's disease: A multicenter case-control study. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:3061–70. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2396-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmer J, Eriksdotter M, Schultzberg M, Pussinen PJ, Buhlin K. Association between periodontitis and risk of Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment and subjective cognitive decline: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:1287–98. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martande SS, Pradeep AR, Singh SP, Kumari M, Suke DK, Raju AP, et al. Periodontal health condition in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014;29:498–502. doi: 10.1177/1533317514549650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cestari JA, Fabri GM, Kalil J, Nitrini R, Jacob-Filho W, de Siqueira JT, et al. Oral Infections and cytokine levels in patients with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment compared with controls. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2016;52:1479–85. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu CH, Ng A, Chau AM, Lo EC. Oral health status of elderly Chinese with dementia in Hong Kong. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13:51–7. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a32343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao SS, Chen KJ, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. The oral health status of Chinese elderly people with and without dementia: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1913. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribeiro GR, Costa JL, Bovi Ambrosano GM, Rodrigues Garcia RC. Oral health of the elderly with Alzheimer's disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okamoto N, Morikawa M, Amano N, Yanagi M, Takasawa S, Kurumatani N. Effects of tooth loss and development of mild Memory impairment in the Fujiwara-Kyo study of Japan: A nested case-control study. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2017;55:575–83. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranjan R, Rout M, Mishra M, Kore SA. Tooth loss and dementia: An oro-neural connection. A cross-sectional study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2019;23:158–62. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_430_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alessandro GD, Costi T, Alkhamis N, Bagattoni S, Sadotti A, Piana G. Oral health status in Alzheimer's disease patients: A descriptive study in an Italian population. J Contemp Dent Prac. 2018;19:483–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo JJ, Yoon JH, Kang MJ, Kim M, Oh N. The effect of missing teeth on dementia in older people: A nationwide population-based cohort study in South Korea. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:61. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0750-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elsig F, Schimmel M, Duvernay E, Giannelli SV, Graf CE, Carlier S, et al. Tooth loss, chewing efficiency and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. Gerodontology. 2015;32:149–56. doi: 10.1111/ger.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ide M, Harris M, Stevens A, Sussams R, Hopkins V, Culliford D, et al. Periodontitis and cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CK, Wu YT, Chang YC. Association between chronic periodontitis and the risk of Alzheimer's disease: A retrospective, population-based, matched-cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9:56. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0282-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamer AR, Morse DE, Holm-Pedersen P, Mortensen EL, Avlund K. Periodontal inflammation in relation to cognitive function in an older adult Danish population. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;28:613–24. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-102004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicciù M, Matacena G, Signorino F, Brugaletta A, Cicciù A, Bramanti E. Relationship between oral health and its impact on the quality life of Alzheimer's disease patients: A supportive care trial. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6:766–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KH, Choi YY. Association between oral health and dementia in the elderly: A population-based study in Korea. Sci Rep. 2019;9:14407. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50863-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naorungroj S, Schoenbach VJ, Beck J, Mosley TH, Gottesman RF, Alonso A, et al. Cross-sectional associations of oral health measures with cognitive function in late middle-aged adults: A community-based study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1362–71. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campos CH, Ribeiro GR, Costa JL, Rodrigues Garcia RC. Correlation of cognitive and masticatory function in Alzheimer's disease. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:573–8. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1923-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dintica CS, Marseglia A, Wårdh I, Stjernfeldt Elgestad P, Rizzuto D, Shang Y, et al. The relation of poor mastication with cognition and dementia risk: A population-based longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:8536–48. doi: 10.18632/aging.103156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurer K, Rahming S, Prvulovic D. Dental health in advanced age and Alzheimer's disease: A possible link with bacterial toxins entering the brain? Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2018;282:132–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sparks Stein P, Steffen MJ, Smith C, Jicha G, Ebersole JL, Abner E, et al. Serum antibodies to periodontal pathogens are a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sochocka M, Zwolińska K, Leszek J. The infectious etiology of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15:996–1009. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666170313122937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uppoor AS, Lohi HS, Nayak D. Periodontitis and Alzheimer's disease: Oral systemic link still on the rise? Gerodontology. 2013;30:239–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syrjälä AM, Ylöstalo P, Ruoppi P, Komulainen K, Hartikainen S, Sulkava R, et al. Dementia and oral health among subjects aged 75 years or older. Gerodontology. 2012;29:36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2010.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatipoglu MG, Kabay SC, Güven G. The clinical evaluation of the oral status in Alzheimer-type dementia patients. Gerodontology. 2011;28:302–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2010.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holtfreter B, Empen K, Gläser S, Lorbeer R, Völzke H, Ewert R, et al. Periodontitis is associated with endothelial dysfunction in a general population: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]