Abstract

Background:

Nature and its products can be utilized for regeneration in periodontal destruction and damage to supporting tissues. We come across the use of various graft materials to reestablish the lost bone and for the long-term survival of teeth. The objective of this study was to evaluate the bone fill efficacy of Morinda citrifolia fruit extract in the periodontal bone defect.

Materials and Methods:

This randomized study included twenty patients indicated for periodontal regenerative therapy and were equally divided and assigned into the experimental and control group. Open flap debridement alone was performed in the control group, while placement of extract along with open flap debridement was done in the experimental group. Clinical parameters assessed were gingival index, probing pocket depth, and relative attachment level, and the amount of bone fill was assessed using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) at baseline and at 6-month interval.

Results:

From the values of clinical parameters, there was a mean reduction in probing pocket and gain in attachment level and a 27.7% increase in bone fill in experimental group as compared to the control group from CBCT analysis.

Conclusions:

The use of M. citrifolia fruit extract in the intraosseous defect was found to be efficacious in terms of relative attachment level and the amount of bone fill, and it had shown some anti-inflammatory affect.

Keywords: Cone beam computed tomography, intraosseous defect, Morinda citrifolia, periodontal regeneration

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is emerging as a matter of concern in the developing countries as, it has a high prevalence rate.[1] The soft- and hard-tissue loss occurred as a result of periodontitis that cannot be managed successfully by nonsurgical therapy alone, requires modalities for the regeneration of lost tissues.[2]

Periodontal regenerative materials and procedures are intended to restore the lost tissue by the new periodontal ligament, cementum, and bone formation by a network of biological phenomenon.[3]

In Indian literature, the utilization of herbs and their products can be referenced for different ayurvedic therapies. The use of natural products has the least side effect and is more economical over synthetic ones.[4] Since decades, periodontics also utilizes herbal products as mouth rinses, toothpastes, local drug delivery agents, and also as a regenerative material.[5]

Over many years, Morinda citrifolia (noni) has been accounted as a crucial herb for its significant medicinal implications and has recently been added as a plant of interest in the field of dentistry. In endodontics as an irrigant,[6] caries inhibiting agent,[7] as a disinfectant when mixed with irreversible hydrocolloid impression,[8] and as a mouth rinse for gingivitis/periodontitis.[9]

M. citrifolia belongs to the coffee family, Rubiaceae and commonly known as Noni or Indian Mulberry. Attributing to its multiple properties, parts of this plant and fruit are used in the treatment of diabetes, hypertension, asthma, bronchitis, arthritis, gout, candidiasis, intestinal colitis, dysmenorrhea, dementia, gingivitis, and periodontitis.[10,11] Its leaves were applied topically on wounds, dislocated, or fractured bones in the ancient Polynesian population, suggesting its role in bone regeneration.

M. citrifolia acts on human periodontal ligament cells by enhancing the differentiation and proliferation of these cells[12] and also by osteoblastic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs).[13]

Thus, the present clinical study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of M. citrifolia fruit extract in periodontal regeneration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of twenty sites of intraosseous defects in periodontitis patients were randomly selected from the outpatient department of periodontics and implantology and were assigned into two groups as experimental and control group.

This study included patients diagnosed as having chronic generalized periodontitis as per 1999 classification of periodontal disease with periodontal pockets of ≥5 mm and radiographic evidence of vertical bone loss, age group between 30 and 55 years, and patients with good general health, and without any history of systemic disease or under medication.

Exclusion criteria were those patients showing unacceptable oral hygiene during presurgical (Phase I) period. Smokers, pregnant women, and lactating mothers were also excluded from the study. Written informed consent form explaining the nature of the study and surgical procedure was signed by the patient. Experimental group was treated with open flap debridement and the placement of noni fruit extract [Figures 1 and 2], whereas the control group was treated with open flap debridement alone [Figure 3]. The clinical parameters at baseline and 6 months were gingival index (Loe and Silness, 1963), probing pocket depth (using UNC-15 probe with occlusal stent), relative attachment level (using UNC-15 probe with occlusal stent), and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) assessment for the intrabony defect.

Figure 1.

Intra-osseous defect after flap reflection

Figure 2.

Placement of Morinda citrifolia fruit extract

Figure 3.

Flap reflection with intra-osseous defect in control group

These fruits were obtained from a local nursery at Anchelpetty, Kerala. The extract was prepared in Pansila “m” Impact Laboratories, Jabalpur. After ripening, the cheesy fruits were washed, chopped, and pieces were allowed to dry. Postdrying, fruit powder was exhaustively extracted with 95% ethanol using a Soxhlet apparatus, and a yield of 50 g was obtained.[14] The total ethanolic extract was concentrated in a vacuum and stored in an airtight sterilized container for utilization as a bone fill material in the periodontal intraosseous defect [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Morinda citrifolia fruit extract in powder form

Statistical analysis

The variables of this study were analyzed using Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software version 21.0, IBM corp. Intragroup comparison at baseline and 6-month interval was measured using repeated measures ANOVA and Fisher's Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc test and intergroup comparison at different time intervals was measured by unpaired t-test.

RESULTS

The clinical parameters and CBCT scans were assessed to analyze the efficacy of the extract.

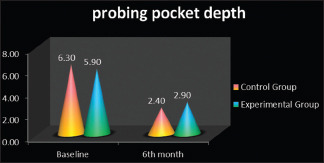

Gingival index scores had shown reduction in gingival inflammation at baseline and at 6 months for both the groups and statistically not significant on intergroup comparison [Table 1]. The probing pocket depth for control group (6.30 ± 0.94) and experimental group (6.90 ± 0.31) at baseline, which was reduced to 3.40 ± 0.82 for control group and 2.90 ± 0.15 for experimental group at 6-month interval as depicted in Table 2 & Graph 1. The mean percentage change at 6 months showed statistically significant improvement in experimental group (61.90%) as compared to the control group (50.84%) (P = 0.01).

Table 1.

Comparison of gingival index scores in control group and experimental group at different time intervals

| Time intervals | Groups | Gingival index scores | Unpaired t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Minimum-maximum | |||

| Baseline | Control group | 1.61±0.26 | 1.20-2.20 | t=1.08, |

| Experimental group | 1.75±0.31 | 1.20-2.20 | P=0.29# | |

| At 6th month | Control group | 0.88±0.13 | 0.60-1.10 | t=1.84, |

| Experimental group | 0.76±0.15 | 0.60-1.10 | P=0.08# | |

#Nonsignificant. SD – Standard deviation; t – t test value; p – probability value (p= 0.01)

Table 2.

Comparison of probing pocket depth scores in control group and experimental group at different time intervals

| Time intervals | Groups | Probing pocket depth | Unpaired t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Minimum-maximum | |||

| Baseline | Control group | 6.30±0.94 | 5.00-8.00 | t=1.05, |

| Experimental group | 5.90±0.31 | 5.00-7.00 | P=0.30# | |

| At 6th month | Control group | 2.40±0.82 | 2.00-4.00 | t=0.52, |

| Experimental group | 2.90±0.15 | 2.00-4.00 | P=0.60# | |

#Nonsignificant. SD –Standard deviation; p – probability value (p= 0.01); t – t test value

Graph 1.

Probing pocket depth scores in control group and experimental group at baseline and 6 months

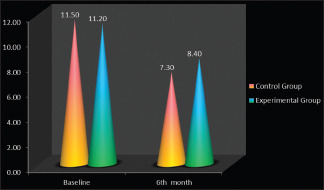

There was a statistically significant gain in relative attachment level scores from baseline to 6-month interval. The mean change in attachment was 11.20 ± 1.03 mm to 8.40 ± 0.67 mm in control group and 11.50 ± 1.03 mm to 8.02 ± 0.67 mm in experimental group [Table 3 & Graph 2].

Table 3.

Comparison of relative attachment level in control group and experimental group at different time intervals

| Time intervals | Groups | Relative attachment levels (mm) | Unpaired t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Minimum-maximum | |||

| Baseline | Control group | 11.20±1.03 | 10-13 | t=0.55, |

| Experimental group | 11.50±1.03 | 10-13 | P=0.58# | |

| At 6th month | Control group | 8.40±0.67 | 7-9 | t=0.32, |

| Experimental group | 8.02±0.67 | 7-9 | P=0.74# | |

#Nonsignificant. SD –Standard deviation; p – probability value (p= 0.01); t – t test value

Graph 2.

Comparison of relative attachment level in control group and experimental group at different time intervals

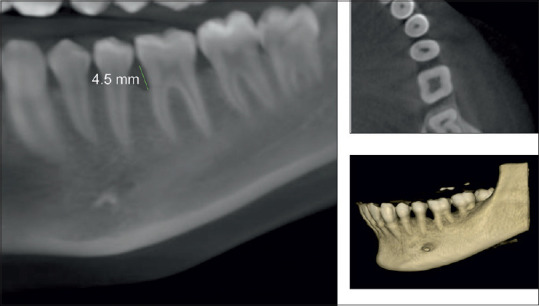

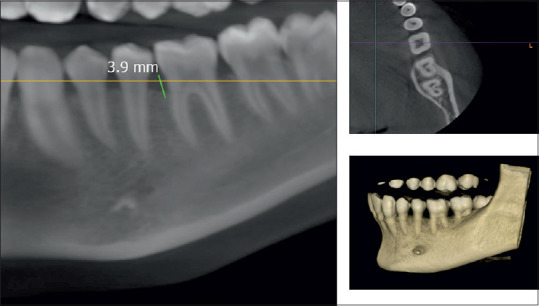

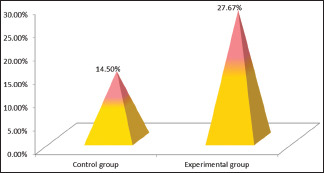

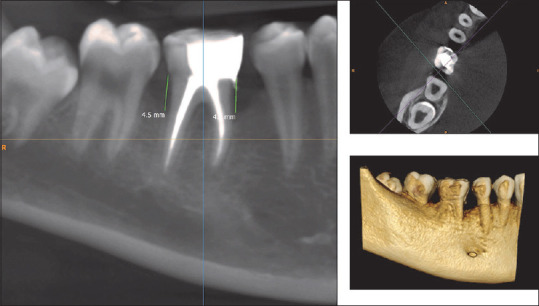

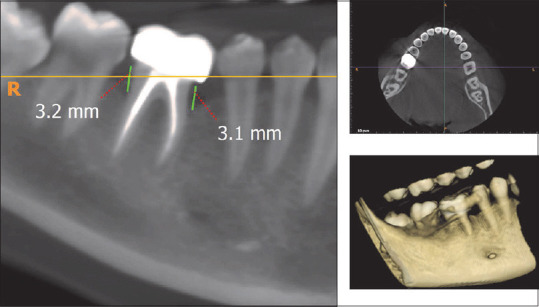

CBCT assessment of bone defect fill showed statistically significant difference from baseline to 6 months. Bone fill score at baseline for control group was found to be 5.14 ± 0.65 mm [Figures 5 and 6] and was 4.59 ± 0.75 mm in experimental group. After 6-month interval, scores for control group were 4.39 ± 0.58 mm and experimental group were 3.32 ± 0.40 mm (P = 0.01) [Table 4, Graph 3 and Figures 7,8], with a mean percentage improvement 27.67% in experimental group as compared to the control group which was 14.50%.

Figure 5.

Pre-cone-beam computed tomography showing intraosseous defect in axial, coronal, and three-dimensional view

Figure 6.

Post-cone-beam computed tomography showing intraosseous defect in axial, coronal, and three-dimensional view

Table 4.

Comparison of cone beam computed tomography assessment of bone fill in control group and experimental group at different time intervals

| Time intervals | Groups | Radiographic assessment | Unpaired t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Minimum-maximum | |||

| Baseline | Control group | 5.14±0.65 | 4.3-6.3 | t=0.55, P=0.58# |

| Experimental group | 4.59±0.75 | 3.40-6.10 | ||

| At 6th month | Control group | 4.39±0.58 | 3.2-5.1 | t=4.74, P=0.01* |

| Experimental group | 3.32±0.40 | 3.10-4.00 | ||

*Significant, #Nonsignificant. SD –Standard deviation; p – probability value (p= 0.01); t – t test value

Graph 3.

Mean percentage change in cone-beam computed tomography assessment in control group and experimental group at different time intervals

Figure 7.

Pre-cone-beam computed tomography showing intraosseous defect in axial, coronal, and three-dimensional in the experimental group

Figure 8.

Post-cone-beam computed tomography showing intraosseous defect in axial, coronal, and three-dimensional view in the experimental group

DISCUSSION

Periodontal flap surgical procedure is a conventional method which helps in debridement of the diseased tissue, thereby reducing periodontal pocket, but they offer limited potential toward restoring the lost and destroyed periodontium. Hence, there is a scope of periodontal regenerative procedure in reconstruction of periodontium.[15] The periodontal regeneration mainly focuses on the formation and restoration in the lost architecture of altered periodontium.[16]

Studies conducted by Pawar et al.,[17] Guo et al.,[18] Lal et al.[19] and Kara et al.[20] suggested that few herbs such as Drynaria quercifolia, Cissus quadrangularis, Salvia miltiorrhiza, Nigella sativa, and M. citrifolia have the ability to promote wound healing and bone repair. They are known as bone knitting herbs.[17]

M. citrifolia popularly known as noni is one of the ancient medicinal plants of Polynesian and Southeast Asian origin. Its widespread use has been documented in various places including India. Most of the parts of the plant owns curative quality.[21]

Boonanantanasarn et al. suggested that, in addition to promoting wound healing, noni leaf extract had also been reported in decreasing inflammation and aiding in tissue repair in patients with fractures and dislocations.[12]

There was a significant reduction in gingival inflammation after the use of M. citrifolia extract through its anti-inflammatory property by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase, as proposed by Masuda et al., antibacterial activity against oral microorganism including periodontopathogens.[22]

The amount of bone fill was increased after 6 month postoperatively, and bone regeneration is contributed to various components of noni extract to induce osteogenic differentiation. The prime phytochemical constituents of the noni plant includes ascorbic acid, flavonoids, alkaloids, iridioids, anthraquinones, terpenes, rutin, carotene, b-sitoserol, linoleic acid, amino acid, scopoletin, octanoic acid, potassium, calcium, and phosphorus. These ingredients contribute to its active role in various ailments.[23]

Shirwaikar et al. in their study reported that the methanolic extract of noni fruit has abundance of flavonoids that has anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, antiestrogenic as well as osteogenic potential. When ovariectomized rats were treated with its extract, it showed elevated levels of biomarkers such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) which increases osteoblastic activity, tartarate resistant acid phosphatase, and hydroxyproline showing its decrease in osteoclastic activity suggesting bone remineralization.[24]

The mechanism in the regeneration of periodontal tissue was described by Boonanantanasarn et al., in their in vitro study on human periodontal ligament cells using M. citrifolia leaf extract, in which Morinda-treated group has shown increased cellular proliferation, increase in ALP activity up to 4 fold during 3–4 weeks suggesting osteogenic inducing property. The calcified nodule formed in noni-treated cells stained bright red with alizarin red stain indicating mineralization.[12]

As evident from the work of Hussain et al., M. citrifolia juice induced osteoblastic differentiation in BMSC by cell proliferation and expression of runt-related transcription factor-2 (RUNX2) transcription factor which upregulates bone biomarkers such as osteocalcin and ALP gene which describes osteoblastic activity.[13]

Shalan et al. observed bone regeneration in estrogen deficient rat using noni leaves and black tea extracts. The results were the increase in bone density and mineralization dose dependently in noni leaf with an increase in biomarkers such as bone morphogenic protein 2, osteoprotegrin, RUNX2, and decrease in inflammatory cytokine such as interleukin-6, preventing osteoclastic activity through receptor activator of nuclear kappa-B ligand.[25]

Bone regeneration is further enhanced by other components such as flavonoids; it accelerates differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells, triterpenes have the potential to increase rate of cell proliferation in wound healing, protein synthesis, and increase in biomarker ALP activity by transforming growth factor beta signaling pathway.[26]

All the above mechanisms suggest the bone regeneration potential of M. citrifolia fruit extract in the intraosseous bone defects as observed in the CBCT radiographs.

The use of CBCT radiographs had an added advantage over conventional radiographs as it provides more accuracy in the bone status by the 3-dimensional view of the alveolar bone and related structures in coronal, sagittal, and axial planes.[27] The CBCT enabled us to observe for more precise changes in bone regeneration prior and after 6 months of noni graft placement.

CONCLUSIONS

In the present study, there was statistically significant reduction in probing pocket depth and gain in relative attachment level in both the groups. CBCT assessment of the bone fill revealed statistically significant changes in both the groups after 6 months, with slightly more bone fill observed in the experimental group. For future consideration, histological and molecular assessment of the bone fill on larger study sample is needed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Our sincere gratitude to Dr. Ankit Dhimole, MDS, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology (Oracle CBCT centre) for his valuable insight and expertise that assisted as throughout the study process. We are also immensely grateful to S. Goshal (Pansila “m” impact) for the processing of the extract.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balaji SK, Lavu V, Rao S. Chronic periodontitis prevalence and the inflammatory burden in a sample population from South India. Indian J Dent Res. 2018;29:254–9. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_335_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortellini P, Tonetti MS. Clinical concepts for regenerative therapy in intrabony defects. Periodontol 2000. 2015;68:282–307. doi: 10.1111/prd.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang HL. Academy report on periodontal regeneration. Position Paper. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1601–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.9.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma S, Singh SP. Current and future status of herbal medicines. Vet World. 2008;1:347. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anarthe R, Mani A, Kale P, Maniyar S, Anuraga S. Herbal approaches in periodontics. Gal Int J Heal Sci Res. 2017;2:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podar R, Kulkarni GP, Dadu SS, Singh S, Singh SH. In vivo antimicrobial efficacy of 6% Morinda citrifolia, Azadirachta indica, and 3% sodium hypochlorite as root canal irrigants. Eur J Dent. 2015;9:529–34. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.172615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumarasamy B, Manipal S, Duraisamy P, Ahmed A, Mohanaganesh S, Jeevika C. Role of aqueous extract of Morinda citrifolia (Indian noni) ripe fruits in inhibiting dental caries-causing Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus mitis. J Dent (Tehran) 2014;11:703–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed AS, Charles PD, Cholan R, Russia M, Surya R, Jailance L. Antibacterial efficacy and effect of Morinda citrifolia L.mixed with irreversible hydrocolloid for dental impressions: A randomized controlled trial. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7:S597–9. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.163562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glang J, Falk W, Westendorf J. Effect of Morinda citrifolia L. fruit juice on gingivitis/periodontitis. Mod Res Inflamm. 2013;2:21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang MY, West BJ, Jensen CJ, Nowicki D, Su C, Palu AK, et al. Morinda citrifolia (Noni): A literature review and recent advances in noni research. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2002;23:1127–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres MA, de Fátima Braga Magalhães I, Mondêgo-Oliveira R, de Sá JC, Rocha AL, Abreu-Silva AL. One plant, many uses: A review of the pharmacological applications of Morinda citrifolia. Phytother Res. 2017;31:971–9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boonanantanasarn K, Janebodin K, Suppakpatana P, Arayapisit T, Chunhabundit P, Rodsutthi J, et al. Morinda citrifolia leaf enhances in vitro osteogenic differentiation and matrix mineralization by human periodontal ligament cells. Dentistry. 2012;2:130. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain S, Tamizhselvi R, George L, Manickam V. Assessment of the role of noni (Morinda citrifolia) juice for inducing osteoblast differentiation in isolated rat bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Stem Cells. 2016;9:221–9. doi: 10.15283/ijsc16024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muenmuang C, Narasingha M, Phusantisampan T, Sriariyanun M. Chemical profiling of Morinda citrifolia extract from solvent and soxhlet extraction method. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Science. 2017:119–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nath GS, Harikumar K. Periodontal flap procedures. A review. Kerala Dent J. 2011;34:175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds MA, Kao RT, Nares S, Camargo PM, Caton JG, Clem DS, et al. Periodontal regeneration—intrabony defects: Practical applications from the AAP regeneration workshop. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2015;5:21–9. doi: 10.1902/cap.2015.140062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pawar V, Chandrashekar KT, Mishra R, Tripathi V, Tripathi K. Drynaria Quercifolia Plant Extract as A Bone Regenerative Material in The Treatment of Periodontal Intrabony Defects:Clinical And Radiographic Assessment. IOSR J dent and med sciences. 2017;16:93–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo Y, Li Y, Xue L, Severino RP, Gao S, Niu J, et al. Salvia miltiorrhiza: An ancient Chinese herbal medicine as a source for anti-osteoporotic drugs. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155:1401–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lal N, Dixit J. Biomaterials in periodontal osseous defects. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2012;2:36–40. doi: 10.1016/S2212-4268(12)60009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kara MI, Erciyas K, Altan AB, Ozkut M, Ay S, Inan S. Thymoquinone accelerates new bone formation in the rapid maxillary expansion procedure. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan-Blanco Y, Vaillant F, Perez AM, Reynes M, Brillouet JM, Brat P. The noni fruit (Morinda citrifolia L.): A review of agricultural research, nutritional and therapeutic properties. J Food Compost Anal. 2006;19:645–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masuda M, Murata K, Naruto S, Uwaya A, Isami F, Matsuda H. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 inhibitory activities of Morinda citrifolia seed extract and its constituents in UVA-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:210–5. doi: 10.1248/bpb.35.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potterat O, Hamburger M. Morinda citrifolia (Noni) fruit--phytochemistry, pharmacology, safety. Planta Med. 2007;73:191–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirwaikar A, Nanda S, Parmar V, Khan S. Methanol extract of the fruits of morinda citrifolialinn., restores bone loss in ovariectomized rats. Int J Pharmacol. 2011;7:446–54. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shalan NA, Mustapha NM, Mohamed S. Noni leaf and black tea enhance bone regeneration in estrogen-deficient rats. Nutrition. 2017;33:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang JF, Li G, Chan CY, Meng CL, Lin MC, Chen YC, et al. Flavonoids of Herba Epimedii regulate osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells through BMP and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;314:70–4. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DM, Bassir SH. When is cone-beam computed tomography imaging appropriate for diagnostic inquiry in the management of inflammatory periodontitis? An American Academy of Periodontology best evidence review? J Periodontol. 2017;88:978–98. doi: 10.1902/jop.2017.160505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]