Abstract

Context:

Adolescents experience many types of gingival and periodontal diseases, including gingivitis, localized or generalized aggressive periodontitis, and periodontal complications of various systemic diseases. The occurrence of periodontal diseases is not only related to biotic factors but may also be affected by nonbiotic factors such as oral health behaviors and practices. Various factors that influence an individual's health-related behaviors include a psychosocial construct named sense of coherence (SOC).

Aim:

The aim of this study is to investigate the association of SOC with oral health behaviors and gingival bleeding.

Settings and Design:

This was a cross-sectional, analytical study that was done in the school setting.

Materials and Methods:

A random sample of 850 adolescents was selected from nine schools of the Faridabad block of Faridabad district (Haryana) through the multistage cluster sampling technique. Methods of data collection included a combination of questionnaire administration and clinical examination. The questionnaire comprised sociodemographic variables, questions related to oral health behaviors, and Antonovsky's SOC scale. The questionnaire was interviewer administered.

Statistical Analysis:

Unadjusted and adjusted rate ratios of gingival units having bleeding on probing were estimated by Poisson regression multilevel analysis in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software for Microsoft Office.

Results:

Adolescents whose mothers had studied <8 years (relative risk [RR] 1.26; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.38), who were males (RR 1.198; 95% CI 1.01–1.29), low SOC (RR 15.93; 95% CI 13.06–19.35), and toothbrushing frequency of less than once a day (RR 1.43; 95% CI 1.21–1.67) and children with plaque index >1 (RR 2.765; 95% CI 2.12–3.25) presented with the higher number of gingival units having bleeding.

Conclusion:

SOC is associated with gingival bleeding through oral health behaviors.

Keywords: Gingival bleeding, oral health, oral health behaviors, psychosocial factors, sense of coherence

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is considered a tender stage in life, when numerous physical and psychological changes take place and oral diseases can cause major suffering and embarrassment and impairing self-esteem and confidence.[1] Further, during this period only, many risky behaviors for developing oral diseases become established, such as dietary habits and tobacco use, which can have a long-lasting adverse impact on the quality of life.[2]

Global oral health trends showed that children usually suffer from dental caries, whereas many adolescents also have symptoms of periodontal disease.[3] According to the available literature, adolescents experience many types of gingival and periodontal diseases, including gingivitis, localized or generalized aggressive periodontitis, and periodontal complications of various systemic diseases.[4] Future oral health status can be predicted from these types of dental diseases in the early phases of life. Thus, effective preventive and control strategies are required at this stage only.[5]

To understand and explain various oral diseases, several conceptual models have been proposed, which have focused on either biomedical or psychological factors of dental caries and periodontal diseases.[6] A few among these models have focused on both the dimensions.[7,8]

The salutogenic theory is one such approach that explains those factors that promote health as distinct from those that modify the risk of any specific disease.[9,10] This theory focuses on the psychosocial determinants of good health rather than etiological factors.[11] Sense of coherence (SOC) is the central feature of the salutogenic theory. It evaluates the individual's capability to use existing resources to overcome difficulties and to cope with life stressors to perform healthy behavior and stay well.[10,11] People with stronger SOC not only have better-coping ability with existing stressors in their society but also have higher tenacity for superior Oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL).[10,12,13] SOC is a composite of following three key competencies: comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness, which have dynamic interactions among them.[10,11,12] Among people with a stronger SOC, better health and quality of life are anticipated with fewer symptoms in case of existing illness.[14,15]

Literature suggests an inverse relationship between SOC and incidence of chronic diseases and subsequently directly proportional to a better quality of life.[16,17,18,19] The occurrence of periodontal diseases is not only related to biotic factors but may also be affected by nonbiotic factors such as oral health behaviors and practices.[20,21] Manifesting through individual behaviors, SOC also influences various psychosocial and environmental factors invariably.[21,22]

There is a paucity of data elucidating the importance of SOC as a determinant of gingival diseases among Indian adolescents. Thus, the present study was taken up to investigate the association of SOC with oral hygiene habits and gingival bleeding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethical committee. A pilot study was conducted among 50 adolescents who were 12–15 years old for checking the feasibility of the study, sample size calculation, and reliability assessment of SOC questionnaire among Indian adolescents. These data were not included in the main study.

The sample size was estimated using nMaster software (Version 2.0, cmcbiostatistics, Vellore, India) after the pilot run of the study. The sample size was calculated considering an outcome (bleeding on probing) prevalence of 0.50, a confidence interval (CI) of 95%, and an error margin of 5%. Taking into account a design effect equal to 2 and possible nonanswers and losses (10%), the sample calculated as 845 participants which were rounded off to 850.

The required number of adolescents, i.e., 850, was recruited from nine schools of the Faridabad block of Faridabad district (Haryana) through the multistage cluster sampling technique. The study population comprised 455 (53.5%) boys and 395 (46.5%) girls. An equal representation of rural, peri-urban, and urban schools was taken into consideration. Permissions were taken from the principals/head of the schools, and the day of the visit to the school was scheduled. Thereafter, two sections were randomly selected from the school among all the sections of Standard 7–9. All the students present in the selected sections were explained about the study and given the information sheet along with the consent form. They were asked to get it signed by their parents till the next scheduled visit. Those students who were willing for the clinical examination and whose parents signed the consent form were included in the study. However, those who were medically compromised or undergoing orthodontic treatment or had mixed dentition were excluded.

Data collection included a combination of questionnaire administration and clinical examination. The questionnaire comprised information regarding sociodemographic data such as age, sex, and parental educational level. It also contained questions related to oral health behaviors (number of dental visits in the last year and frequency of oral cleaning) and Antonovsky's SOC scale. The questionnaire was interviewer administered.

The SOC questionnaire consisted of 13 items, distributed in three domains, i.e., comprehensibility (five items), manageability (four items), and meaningfulness (four items). Every item was scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7. This SOC questionnaire was translated to Hindi and then further validated in the adolescent population before using it. The scores for negatively worded items (question number 1, 2, 3, 7, and 10) were reversed for calculations. Sum score of SOC ranged from 13 to 91; a higher score indicating high SOC. Items were averaged to calculate the SOC score of each subject. Those subjects who did not answer more than three SOC items were excluded from the sample. If a subject did not answer for three or fewer SOC items, then missing items were replaced by the mean value of the remaining SOC items. The reliability of the SOC questionnaire in the present study sample was assessed by Cronbach's alpha, whose value came as 0.85. The study population was categorized among three groups of SOC, i.e., low SOC, moderate SOC, and high SOC, according to the tertiles of the SOC distribution.[14]

Oral health behaviors' questionnaire comprised three questions in terms of tobacco usage, dental visiting habits, and oral hygiene habits.

The participants reported their frequency of dental visits during the past 12 months on a 5-point scale (never, once, twice, thrice, and four-time) and their toothbrushing frequency on a 6-point scale (never, several times a month, once a week, several times week, once a day, and two or more times a day). Tobacco chewing and smoking status were also recorded on a 6-point scale (never, several times a month, once a week, several times a week, once a day, and two or more times a day).

Clinical examination was performed by a single trained calibrated examiner, using natural light with a dental mirror and community periodontal index probe. Bleeding on probing concerning all the teeth present was recorded using the WHO criteria, 2013. Plaque index (PI) (Loe and Silness) was also recorded.

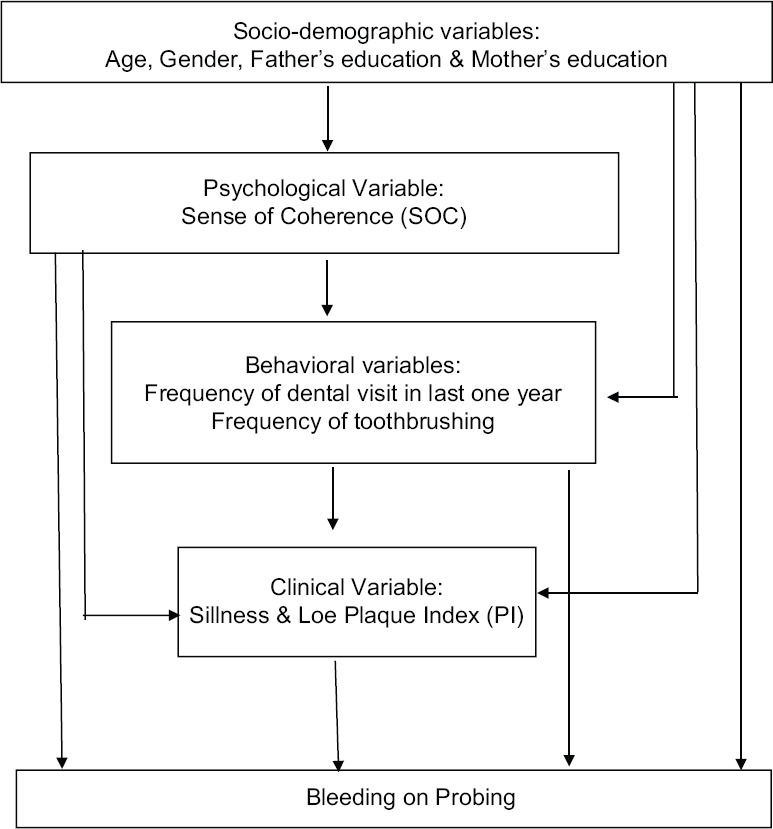

Data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) package version 16 (SPSS, Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptives of categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and of continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Unadjusted and adjusted rate ratios of the gingival units having bleeding on probing were estimated in Poisson regression multivariable analysis. Multivariable analysis following a hierarchical approach was carried out to determine the predictors of gingival bleeding. The criteria suggested by Victora et al. were found to be suitable to study different adolescent's oral health outcomes.[23] Representing distal, mediating, and proximal determinants of the gingival health, variables were divided into four groups [Figure 1]. Sociodemographic factors are the distal determinants influencing all other predictors directly or indirectly. The second group of determinants included the psychosocial variable (SOC), which may affect behavioral predictors. Adjunctly, these variables, in turn, influence clinical variables, i.e., Loe and Silness PI, which may affect adolescent's gingival health. Then, multivariable modeling was carried out, which included only explanatory variables presenting with a P ≤ 0.20 in the unadjusted analysis, except for sex and age, which remained in the models, irrespective of the P value. Therefore, the final model estimated rate ratios for the selected variables after adjusting for the variables of the same level or upper variables selected in the final model. Statistical significance for predictors after adjustments was set at P < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for bleeding on probing among adolescents

RESULTS

The present study recruited 850 adolescents for data collection, but the analysis was done for the data from 811 adolescents (52.4% males and 47.6% females). Remaining 39 adolescents were excluded for missing entries for more than three items of SOC questionnaire. The intraexaminer agreement (as assessed by Kappa coefficient) regarding gingival bleeding and PI was found to be 0.93 and 0.89, respectively. Sociodemographic, psychological, behavioral, and clinical profile of the study population is reported in Table 1. The study subjects comprised 425 (52.4%) males and 386 (47.6%) females. The mean age of the finally analyzed sample was 13.38 years (SD = 1.02, range 12–15 years). The majority of them reported once or more as the frequency of daily oral cleaning. The proportion of adolescents who visited a dental clinic in the last year was 45.7%. Gingival bleeding on probing was found to be present among 338 (41.7%) adolescents. Among these, the mean number of gingival units showing bleeding was 6.7 ± 4.6. The mean SOC score of the study population was 53.18 ± 13.37.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, psychological, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of the study population

| Absolute frequency (n) | Relative frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 12 | 197 | 24.3 |

| 13 | 234 | 28.9 |

| 14 | 254 | 31.3 |

| 15 | 126 | 15.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Males | 425 | 52.4 |

| Females | 386 | 47.6 |

| Mother’s education | ||

| <8 years of schooling | 177 | 21.8 |

| ≥8 years of schooling | 538 | 66.3 |

| Graduation/postgraduation/ professionally qualified | 96 | 11.8 |

| Father’s education | ||

| <8 years of schooling | 59 | 7.3 |

| ≥8 years of schooling | 554 | 68.3 |

| Graduation/postgraduation/ professionally qualified | 198 | 24.4 |

| SOC | ||

| Low (1st tertile, i.e., up to 40 score) | 272 | 33.5 |

| Moderate (2nd tertile, i.e., from 41 to 66 score) | 274 | 33.8 |

| High (3rd tertile, i.e., above 66 score) | 265 | 32.7 |

| Dental visits in the last 1 year | ||

| No | 440 | 54.3 |

| Yes | 371 | 45.7 |

| Tooth brushing frequency | ||

| Less than once a day | 78 | 9.6 |

| Once or more times a day | 733 | 90.4 |

| Gingival bleeding | ||

| No | 473 | 58.3 |

| Yes | 338 | 41.7 |

SOC – Sense of coherence; n – number

Unadjusted Poisson regression analysis [Table 2] showed that gender, mother's education, SOC, having visited the dentist in the last 1 year, toothbrushing frequency of less than once a day, and the presence of dental plaque were significantly associated with gingival bleeding. The total number of gingival units having bleeding did not show any significant association with age and father's educational level.

Table 2.

Unadjusted assessment of sociodemographic, psychosocial, behavioral, and clinical variables associated with the number of gingival units having bleeding on probing (poisson multilevel regression analysis)

| Variables | Mean gingival units having bleeding ≥1 | RR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||

| Age | - | 0.975 | 0.936-1.015 | 0.212 |

| Gender | ||||

| Boys | 0.4329±0.496 | 1.227 | 1.129-1.333 | 0.0023 |

| Girls | 0.399±0.386 | 1 | - | |

| Mother’s education | ||||

| <8 years of schooling | 0.373±0.485 | 1.562 | 1.027-1.983 | 0.007 |

| ≥8 years of schooling | 0.420±0.494 | 1.123 | 0.959-1.632 | 0.167 |

| Graduation/postgraduation/professionally qualified | 0.479±0.502 | 1 | - | - |

| Father’s education | ||||

| <8 years of schooling | 0.458±0.502 | 1.107 | 0.939-1.305 | 0.277 |

| ≥8 years of schooling | 0.394±0.489 | 0.946 | 0.859-1.041 | 0.255 |

| Graduation/postgraduation/professionally qualified | 0.470±0.500 | 1 | - | - |

| Psychosocial variable | ||||

| SOC | ||||

| Low | 0.809±0.394 | 5.562 | 3.846-7.841 | <0.0001 |

| Middle | 0.303±0.460 | 3.328 | 2.694-4.112 | 0.002 |

| High | 0.132±0.339 | 1 | - | - |

| Behavioral variable | ||||

| Dental visit (in last 1 year) | ||||

| No | 1.757 | 1.346-2.045 | 0.011 | |

| Yes | 1 | - | - | |

| Toothbrushing frequency | ||||

| Less than once a day | 1.255 | 1.105-1.426 | 0.007 | |

| Once or more times a day | 1 | - | - | |

| Clinical variable | ||||

| PI > 1 | 3.472 | 2.984-3.869 | 0.001 | |

| PI ≤ 1 | 1 | - | - |

*Statistically significant, level of statistical significance set at P<0.05. RR – Relative risk; CI – Confidence interval; SOC – Sense of coherence; PI – Plaque index

After the adjustments, the variables that emerged as significant predictors of the gingival bleeding were the gender, mother's education, SOC, toothbrushing frequency, and dental plaque [Table 3]. Adolescents whose mothers had studied <8 years (relative risk [RR] 1.26; 95% CI 1.04–1.38), who were males (RR 1.198; 95% CI 1.01–1.29), low SOC (RR 15.93; 95% CI 13.06–19.35), and toothbrushing frequency of less than once a day (RR 1.43; 95% CI 1.21–1.67) and children with PI >1 (RR 2.765; 95% CI 2.12–3.25) presented with the higher number of gingival units having bleeding than their counterparts [Table 3].

Table 3.

Multilevel Poisson regression on the association between socioeconomic, demographic, psychosocial, behavioral, and clinical variables and the number of gingival units having bleeding on probing

| Variables | RR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||

| Age | 0.983 (0.943-1.025) | 1.027 (0.984-1.7220) | 1.032 (0.989-1.077) | 1.054 (1.01-1.23) |

| Gender | ||||

| Girls | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Boys | 1.255 (1.154 -1.365)* | 1.213 (1.115-1.319)* | 1.210 (1.11-1.32)* | 1.198 (1.01-1.29)* |

| Mother’s educational level | ||||

| Graduation/postgraduation/professionally qualified | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥8 years of schooling | 1.384 (1.114 - 1.705)* | 1.213 (1.017-1.452) | 1.003 (0.89-1.13) | 1.01 (0.92-1.27) |

| <8 years of schooling | 1.680 (1.488-1.786)* | 1.456 (1.213-1.784)* | 1.213 (1.02-1.324)* | 1.26 (1.04-1.38)* |

| Psychosocial variable | ||||

| SOC | ||||

| High | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Middle | 3.33 (2.70-4.12)* | 3.26 (2.64-4.03)* | 3.37 (2.32-4.02)* | |

| Low | 15.32 (12.82-18.82)* | 15.71 (12.96-19.04)* | 15.93 (13.06-19.35)* | |

| Behavioral variable | ||||

| Dental visit | ||||

| Yes | 1 | Not entered in the model | ||

| No | 0.938 (0.834-1.02) | |||

| Toothbrushing frequency | ||||

| Once or more times a day | 1 | 1 | ||

| Less than once a day | 1.323 (1.12-1.563)* | 1.43 (1.21-1.67)* | ||

| Clinical variable | ||||

| PI ≤ 1 | 1 | |||

| PI > 1 | 2.765 (2.12–3.25)* | |||

*Statistically significant, level of statistical significance set at P<0.05. RR – Relative risk; CI – Confidence interval; SOC – Sense of coherence; PI – Plaque index

DISCUSSION

A recent report from the WHO shows that juvenile-onset aggressive periodontitis, preceded by chronic gingivitis, affects approximately 2% of youth.[24] Literature suggests that periodontal health during the early years of life is positively associated with periodontal diseases at later stages.[25] This fact justifies the importance of early detection and prompt treatment of gingivitis at its initiation.[26] An investigation into the risk factors associated with gingivitis in the early phases may help understand disease progression and predict which patients will require special treatment.

Literature also suggests a direct relationship between oral, social, and psychological issues.[15,27] Several studies found an association between high SOC and positive health behaviors, such as maintenance of good oral hygiene, prescription adherence, not taking up smoking, lower consumption of alcohol, and healthy physical activities.[28] Few studies also proved that SOC plays the role of a protective factor by reducing the impact caused by adverse life events, such as illness.[29]

The hierarchical approach was used to detect the indirect effect of a distal determinant on the gingival bleeding.[30] In the present research, the chances of having gingival bleeding were mediated by the socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical determinants and SOC. Adolescents with higher SOC scores were found to have a lesser number of gingival units showing bleeding as compared to those with lower SOC. According to the salutogenic theory, one possible explanation by which SOC might lead to better oral health is by promoting healthy behaviors.[29] The multilevel analysis demonstrated that SOC might exert its positive impact by influencing adolescent's dental visits and positive oral health behaviors such as toothbrushing. Thus, dental attendance and once or more daily toothbrushing might be the mediators through which SOC promotes gingival health.

This finding of the study corroborated with previous research by Lindmark et al. among Swedish adults, where the researchers found a significant association of SOC with periodontal disease.[31] However, another study which used the data from the Finnish Health 2000 Survey was not as per the results of the present study.[14]

The strength of the present study lies in the large sample size reinforcing the validity of its findings and considerable power. For instance, the sample size was more than adequate, allowing a considerable power of the study. Moreover, the use of validated instruments and the acceptable level of intraexaminer agreement increased the reliability of results.

There is a limitation of the present study, i.e., the cross-sectional nature of the study limits its use in establishing the causal association between outcomes and predictors. Nevertheless, cross-sectional studies are important to study designs for identifying risk indicators; however, at the same time, they are not able to establish temporality. Hence, further longitudinal studies are required to establish risk indicators as risk factors.

Further, the high response rate from study subjects increased internal validity. Despite the potential mentioned limitations, the data of the present study can contribute to improve the understanding of the linkages between various predictors of gingival bleeding. The findings of the present study can help design and implement various health promotion interventions targeted toward the improvement in SOC.

CONCLUSION

This study suggested that SOC is associated with gingival bleeding through oral health-related behaviors. Research opportunities are present in the field of development of interventions targeted toward the improvement of SOC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silva AL, Mattos IE, Carmo CN. Factors associated with self-rated oral health in adolescents in São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil, 2014. Ann Dent Oral Health. 2018;2:1008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuta M, Ekuni D, Takao S, Suzuki E, Morita M, Kawachi I. Social capital and self-rated oral health among young people. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin LJ, Lamster IB, Greenspan JS, Pitts NB, Scully C, Warnakulasuriya S. Global burden of oral diseases: Emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis. 2016;22:609–19. doi: 10.1111/odi.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jürgensen N, Petersen PE. Promoting oral health of children through schools-results from a WHO global survey 2012. Community Dent Health. 2013;30:204–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freire MC, Sheiham A, Hardy R. Adolescents' sense of coherence, oral health status, and oral health-related behaviours. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:204–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reisine S, Litt M. Social and psychological theories and their use for dental practice. Int Dent J. 1993;43:279–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriksson AK, van den Donk M, Hilding A, Östenson CG. Work stress, sense of coherence, and risk of type 2 diabetes in a prospective study of middle-aged Swedish men and women. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2683–9. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watt RG. Emerging theories into the social determinants of health: Implications for oral health promotion. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:241–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sipilä K, Ylöstalo P, Könönen M, Uutela A, Knuuttila M. Association of sense of coherence and clinical signs of temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2009;23:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsson M, Hansson K, Lundblad AM, Cederblad M. Sense of coherence: Definition and explanation. Int J Soc Welf. 2006;15:219–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: A systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:376–81. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.041616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsson V, Hakeberg M, Wide Boman U. Associations between dental anxiety, sense of coherence, oral health-related quality of life and health behaviour-a national Swedish cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:100. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0088-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernabe× E, Kivimaki M, Tsakos G, Suominen-Taipale AL, Nordblad A, Savolainen J, et al. The relationship among sense of coherence, socio-economic status, and oral health-related behaviors among Finnish dentate adults. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:413–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freire M, Hardy R, Sheiham A. Mothers' sense of coherence and their adolescent children's oral health status and behaviours. Community Dent Health. 2002;19:24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonovsky A, Matarazzo JD, editors. Behavioral Health: A Handbook of Health Enhancement and Disease Prevention. 1st ed. NewYork, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1984. The sense of coherence as a determinant of health; pp. 114–29. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moons P, Norekvål TM. Is sense of coherence a pathway for improving the quality of life of patients who grow up with chronic diseases? A hypothesis? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;5:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helvik AS, Engedal K, Selbæk G. Sense of coherence and quality of life in older in-hospital patients without cognitive impairment-a 12 month follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rakizadeh E, Hafezi F. Sense of coherence as a predictor of quality of life among Iranian students living in Ahvaz. Oman Med J. 2015;30:447–54. doi: 10.5001/omj.2015.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorri M, Sheiham A, Watt RG. Modeling the factors influencing general and oral hygiene behaviors in adolescents. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:261–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2010.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elyasi M, Abreu LG, Badri P, Saltaji H, Flores-Mir C, Amin M. Impact of sense of coherence on oral health behaviors: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: It's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MT. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: A hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:224–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century-the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl 1):3–23. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu HX, Wong MC, Lo EC, McGrath C. Trends in oral health from childhood to early adulthood: A life course approach. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39:352–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.da Silva Pde L, Barbosa Tde S, Amato JN, Montes AB, Gavião MB. Gingivitis, psychological factors and quality of life in children. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13:227–35. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a32344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandes IB, Costa DC, Coelho VS, Sá-Pinto AC, Ramos-Jorge J, Ramos-Jorge ML. Association between sense of coherence and oral health-related quality of life among toddlers. Community Dent Health. 2017;34:37–40. doi: 10.1922/CDH_3960Fernandes04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coutinho VM, Heimer MV. Sense of coherence and adolescence: An integrative review of the literature. Cien Saude Colet. 2014;19:819–27. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232014193.20712012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomazoni F, Vettore MV, Mendes FM, Ardenghi TM. The association between sense of coherence and dental caries in low social status schoolchildren. Caries Res. 2019;53:314–21. doi: 10.1159/000493537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newton JT, Bower EJ. The social determinants of oral health: New approaches to conceptualizing and researching complex causal networks. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindmark U, Hakeberg M, Hugoson A. Sense of coherence and oral health status in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69:12–20. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.517553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]