Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the perinatal and maternal outcomes of pregnancies in women infected with SARS-CoV-2, comparing spontaneous and in vitro fertilization (IVF) pregnancies (with either own or donor oocytes).

Design

Multicenter, prospective, observational study.

Setting

78 centers participating in the Spanish COVID19 Registry.

Patient(s)

1,347 pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 positive results registered consecutively between February 26 and November 5, 2020.

Intervention(s)

The patients’ information was collected from their medical records, and multivariable regression analyses were performed, controlling for maternal age and the clinical presentation of the infection.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Obstetrics and neonatal outcomes, pregnancy comorbidities, intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation need, and medical conditions.

Result(s)

The IVF group included 74 (5.5%) women whereas the spontaneous pregnancy group included 1,275 (94.5%) women. The operative delivery rate was high in all patients, especially in the IVF group, where cesarean section became the most frequent method of delivery (55.4%, compared with 26.1% of the spontaneous pregnancy group). The reason for cesarean section was induction failure in 56.1% of the IVF patients. IVF women had more gestational hypertensive disorders (16.2% vs. 4.5% among spontaneous pregnancy women, adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 5.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.45–10.93) irrespective of oocyte origin. The higher rate of intensive care unit admittance observed in the IVF group (8.1% vs. 2.4% in the spontaneous pregnancy group) was attributed to preeclampsia (aOR 11.82, 95% CI 5.25–25.87), not to the type of conception.

Conclusion(s)

A high rate of operative delivery was observed in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2, especially in those with IVF pregnancies; method of conception did not affect fetal or maternal outcomes, except for preeclampsia.

Clinical Trial Registration Number

Key Words: COVID-19, pregnancy, intensive care unit, assisted reproduction, cohort study

Abstract

Resultados perinatales en embarazos resultante de técnicas de reproducción asistida en mujeres infectadas con SARS-CoV-2: un estudio observacional prospectivo.

Objetivo

Evaluar los resultados perinatales y maternos de los embarazos en mujeres infectadas con SARS-CoV-2, comparando embarazos espontáneos con los de fecundación in vitro (FIV) (con ovocitos propios o de donantes).

Diseño

Estudio observacional, prospectivo, multicéntrico.

Entorno

78 centros participantes en el Registro Español COVID19

Paciente (s)

1347 mujeres embarazadas con resultados positivos de SARS-CoV-2 registrados consecutivamente entre el 26 de febrero y el 5 de noviembre de 2020.

Intervención (es

): La información de las pacientes se recopiló de sus registros médicos y se realizaron análisis de regresión multivariable, controlado por edad materna y presentación clínica de la infección.

Principales medidas de resultado

resultados obstétricos y neonatales, comorbilidades gestacionales, ingreso en la unidad de cuidados intensivos, necesidad de ventilación y condiciones médicas.

Resultado (s)

El grupo de FIV incluyó 74 (5,5%) mujeres, mientras que el grupo de embarazo espontáneo incluyó a 1275 (94,5%) mujeres. La tasa de partos intervenidos quirúrgicamente fue alta en todas las pacientes, especialmente en el grupo de FIV, donde la cesárea se convirtió en el método más frecuente de parto (55,4%, en comparación con 26,1% del grupo de embarazo espontáneo). El motivo de la cesárea fue el fracaso de la inducción en 56,1% de las pacientes de FIV. Las mujeres con FIV tenían más trastornos hipertensivos gestacionales (16,2% frente a 4,5% entre las mujeres con embarazos espontáneos, con la Odd ratio ajustada [ORa] 5,31, intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 2,45-10,93) independientemente del origen del ovocito. La mayor tasa de ingreso a la unidad de cuidados intensivos observada en el grupo de FIV (8,1% frente a 2,4% en el grupo de embarazo espontáneo) se atribuyó a la preeclampsia (ORa 11,82; IC del 95%: 5,25 a 25,87), y no al tipo de concepción.

Conclusión (es)

Se observó una alta tasa de parto intervenido quirúrgicamente en mujeres embarazadas infectadas con SARS-CoV-2, especialmente en aquellas con gestaciones de FIV; el método de concepción no afectó los resultados maternos o fetales, excepto en el caso de la preeclampsia.

Discuss: You can discuss this article with its authors and other readers at https://www.fertstertdialog.com/posts/32370

With more than 9 × 106 confirmed cases, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is a life-threatening health problem, especially in high risk individuals. The situation was extremely serious in Spain, because it was one of the hardest hit countries in the world (1).

Because of the physiological changes of pregnancy, pregnant women are more vulnerable to respiratory infections (2) and for this reason, pregnancy should be considered a high risk condition during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. There already are several studies that describe the role of this coronavirus in maternal and perinatal outcomes (3, 4, 5, 6).

Currently, we know that pregnant women, compared with nonpregnant women, are more frequently admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU), more likely to receive invasive ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and more likely to die of COVID-19. Whereas an increased risk for severe disease related to pregnancy was apparent in nearly all stratified analyses, older pregnant women (>35 years) with COVID-19 had the worst clinical outcomes (7). In addition, prematurity because of maternal illness was described as an adverse perinatal outcome in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 (8).

Worldwide, the number of couples demanding assisted reproductive technology (ART) is increasing. More than 7 × 106 infants were born after in vitro fertilization (IVF) (9). Earlier publications suggested that pregnancies achieved by IVF or oocyte donation had poorer results compared with those obtained after spontaneous conception in both multiple and singleton pregnancies (10). The IVF condition confers a higher risk of complications such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, low birth weight/small for gestational age, gestational diabetes and preterm delivery, induction of labor, and cesarean section (11, 12, 13). Thus, we could presume that the perinatal outcomes of ART could be even worse during the COVID-19 outbreak, and it is essential to determine if there are increased maternal and/or neonatal risks in this group of women.

For this reason, we decided to evaluate the perinatal and maternal outcomes of pregnancies in SARS-CoV-2-infected women, comparing the results of pregnancies achieved by ART with those of spontaneous conceptions in a large multicenter Spanish cohort. The secondary end point was to evaluate if there were differences in obstetric and perinatal outcomes between women with SARS-CoV-2-positive results whose conceptions were achieved by IVF with their own oocytes vs. outcomes for pregnancies obtained after oocyte donation.

Materials and methods

This was a multicenter, prospective study of consecutive cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a pregnancy cohort registered by the Spanish Obstetric Emergency group (14, 15). The registry protocol was approved by the coordinating hospital’s Medical Ethics Committee on March 23, 2020 (reference number: PI 55/20), and each collaborating center subsequently obtained protocol approval locally; the registry protocol is available at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04558996). A complete list of the 78 centers contributing to the study is provided in Supplemental Table 1 (available online). On recruitment, given the contagiousness of the disease and the lack of personal protection equipment, mothers consented by either signing a document when possible or by giving permission verbally, which was recorded in the patient’s chart. A specific database was designed for recording information regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy, and the lead researcher entered data for each center after delivery, with a follow up of six weeks postpartum. We developed an analysis plan using the recommended contemporaneous methods and followed existing STROBE guidelines for reporting our results (Supplemental Table 2).

Infected Cohort

During the period of the study, from February 26 to November 5, 2020, we selected obstetric patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection detected by testing suspicious cases that came into the hospital with symptoms compatible with COVID-19 and by universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 infection at admission in the delivery ward (starting on April 1 in many hospitals). SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed by positive double-sampling polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) result from nasopharyngeal swabs. All positive cases were included in the study. The cases were classified as asymptomatic and symptomatic, and the latter were stratified into three groups: mild-moderate symptoms (cough, anosmia, fatigue/discomfort, fever, dyspnea), pneumonia, and complicated pneumonia/shock (with ICU admission and/or mechanical ventilation and/or septic shock). There were two waves of a high incidence of SARS-CoV-2 during the study period: March 1 to May 5, 2020 (first wave) and July 14 to November 5 (second wave) (16).

Study Variables

Information regarding the demographic characteristics of each pregnant woman, comorbidities, previous and current obstetric history, and type of conception were extracted from the clinical and verbal history of the patient. For perinatal events, we recorded gestational age at delivery, type of delivery, preterm delivery (<37 weeks), onset of labor, prelabor rupture of membranes (PROM), preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM), medical complications (thromboembolic events, ICU admission, need of invasive ventilation), obstetric complications (hemorrhagic events and gestational hypertensive disorders), stillbirth, and maternal deaths. Neonatal data included 5-minute Apgar score, umbilical artery pH, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, and neonatal deaths. Definitions of clinical and obstetric conditions followed international criteria (17, 18, 19).

Statistical Analysis

The variables maternal age (years) and gestational age at delivery (weeks + days) were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive data are presented as mean (range) or number (percentage). The possible association of IVF conception (vs. spontaneous) and IVF donor oocyte (vs. IVF own oocyte) with the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and baseline and pregnancy characteristics was analyzed using the Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test (after checking the absence of normality of the data using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). On the other hand, the differences in delivery management (vaginal vs. cesarean section) between the SARS-CoV-2 first (March 1 to May 5, 2020) and second (July 14 to November 5, 2020) waves in spontaneous conception and IVF patients were computed by Pearson’s chi-square test. Statistical tests were two-sided and were performed with SPSS V.20 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL); statistically significant associations were considered to exist when the P value was <.05.

For computing measures of association of perinatal and neonatal outcomes with IVF conception (vs. spontaneous) and IVF donor oocyte (vs. IVF own oocyte), the influence of maternal age and clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection (categorized as asymptomatic and symptomatic) were controlled for multivariable logistic regression modeling to derive adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Modeling was performed after excluding pregnancies with missing data. Regression analyses were performed using the lme4 package in R, version 3.4 (RCoreTeam, 2017) (20).

Results

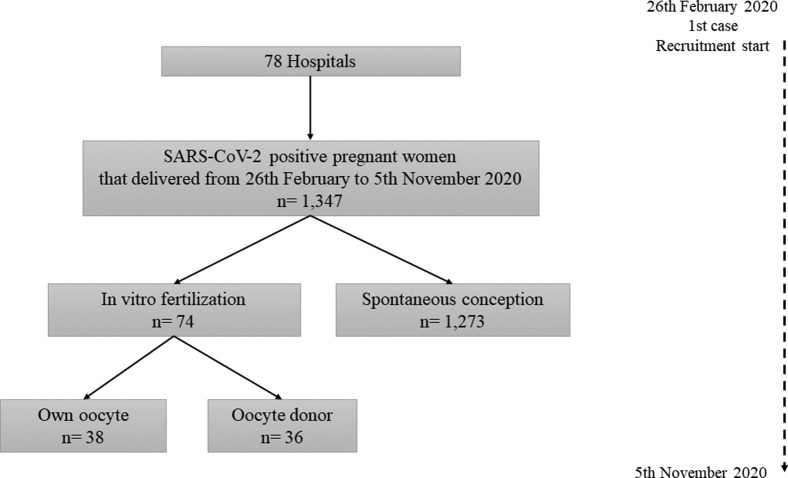

Overall, 1,347 pregnant women with positive SARS-CoV-2 results were identified, completed follow up, and were analyzed. Of these, 1,273 (94.5%) corresponded to spontaneous pregnancies and 74 (5.5%) to pregnancies achieved after ART (Supplemental Figure 1); 38 of 74 (51.4%) of the ART pregnancies were obtained from own oocytes and 36 of 74 (48.6%) from donor oocytes.

The clinical presentation of the SARS-CoV-2 infection is shown in Table 1 . The observed distribution of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients was similar between the conception groups (approximately 50% vs. 50%; P=.166). No significant differences were observed when results were analyzed by clinical presentation, as approximately three-quarters of the symptomatic patients in both groups had mild-moderate symptoms (cough, anosmia, fatigue/discomfort, fever, dyspnea). However, among IVF patients who developed pneumonia, one-third ended in complicated pneumonia/shock, compared with 12.6% in the spontaneous conception patients, although this difference was not statistically significant (P=.106). When IVF with own oocyte and IVF with donor oocyte were compared, no significant differences in terms of COVID-19 symptomatology were observed.

Table 1.

Clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the study participants.

| All patients (n = 1,347) |

IVF patients (n = 74) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVF pregnancies 74 (5.4) | Spontaneous pregnancies 1,273 (94.6) | P value | Own oocyte 38 (51.4) | Donor oocyte 36 (48.6) | P value | |

| Asymptomatic | 32 (43.2) | 656 (51.5) | .166 | 18 (47.4) | 14 (38.9) | .462 |

| Symptomatic | 42 (56.8) | 617 (48.5) | 20 (52.6) | 22 (61.1) | ||

| Mild-moderate symptoms | 33/42 (78.5) | 434/617 (70.3) | .256 | 16/20 (80.0) | 17/22 (77.3) | .000 |

| Pneumonia | 9/42 (21.5) | 183/617 (29.7) | 4/20 (20.0) | 5/22 (22.7) | ||

| Pneumonia | 6/9 (66.7) | 160/183 (87.4) | .106 | 4/4 (100.0) | 2/5 (40.0) | .167 |

| Complicated pneumonia a/shock | 3/9 (33.3) | 23/183 (12.6) | 0/4 (0.0) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

Note: Data shown as number (percent of total). IVF = in vitro fertilization.

With intensive care unit admission and/or mechanical ventilation and/or septic shock.

Table 2 shows the baseline and pregnancy characteristics of patients stratified into the conception groups mentioned previously. The IVF patients were significantly older, with a mean age of 39.6 years (vs. 31.7 years in women with spontaneous conceptions, P<.001) and had 86.5% of patients in the 35–49 age rank (vs. 36.1% of women with spontaneous conceptions). In the IVF patients, the women in the oocyte donor group were older (42.0 [32–49] years vs. 37.2 [31-47] years for own oocyte, P<.001).

Table 2.

Baseline and pregnancy characteristics of the study participants.

| All patients (n = 1,347) |

IVF patients (n = 74) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVF pregnancies (n = 74) | Spontaneous pregnancies (n = 1,273) | P value | Own oocyte (n = 38) | Donor oocyte (n = 36) | P value | |

| Maternal characteristics: | ||||||

| Maternal age (years; mean/range) | 39.6 (31–49) | 31.7 (18–46) | <.001a | 37.2 (31–47) | 42.0 (32–49) | <.001 b |

| 18–24 | 0 (0.0) | 183/1,262 (14.5) | <.001 a | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 b |

| 25–34 | 10 (13.5) | 623/1,262 (49.4) | 8 (21.1) | 2 (5.6) | ||

| 35–49 | 64 (86.5) | 456/1,262 (36.1) | 30 (78.9) | 34 (94.4) | ||

| Ethnicity | <.001 a | .260 | ||||

| White European | 66 (89.2) | 719/1,270 (56.6) | 32 (84.2) | 34 (94.4) | ||

| Latino Americans | 2 (2.7) | 372/1,270 (29.3) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Arab | 4 (5.4) | 106/1,270 (8.3) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (5.6) | ||

| Asian nonhispanic | 2 (2.7) | 38/1,270 (3.0) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Black nonhispanic | 0 (0.0) | 35/1,270 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Rh + | 58/72 (80.6) | 1088/1,217 (89.4) | .020 a | 30/37 (81.1) | 28/35 (80.0) | .908 |

| Nuliparous | 39 (52.7) | 477/1,259 (37.9) | .011 a | 19 (50.0) | 20 (55.6) | .632 |

| Smoking c | 7/72 (9.7) | 124/1,218 (10.2) | .900 | 4/36 (11.1) | 3 (8.3) | 1.000 |

| Maternal comorbidities: | ||||||

| Obesity (BMI>30 kg/m2) | 13/73 (17.8) | 232/1,233 (18.8) | .830 | 6/37 (16.2) | 7 (19.4) | .719 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | ||||||

| Chronic cardiopathy | 0/73 (0.0) | 15/1,243 (1.2) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — |

| Pregestational hypertension | 1/73 (1.4) | 18/1,231 (1.5) | 1.000 | 0/37 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | .493 |

| Pulmonary comorbidities | ||||||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0 (0.0) | 3/1,242 (0.2) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — |

| Asthma | 2/72 (2.8) | 50/1,240 (4.0) | 1.000 | 1/37 (2.7) | 1/35 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| Hematologic comorbidities | ||||||

| Chronic hematologic disease | 2/73 (2.7) | 19/1,239 (1.5) | .328 | 0 (0.0) | 2/35 (5.7) | .226 |

| Thrombophilia | 8 (10.8) | 17/1,236 (1.4) | <.001 a | 3 (7.9) | 5 (13.9) | .474 |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 2/72 (2.8) | 5/1,236 (0.4) | .052 | 1/36 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 1.000 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1/72 (1.4) | 4/1,241 (0.3) | .246 | 0/37 (0.0) | 1/35 (2.9) | .486 |

| Moderate-severe chronic hepatic disease | 0/71 (0.0) | 2/1,236 (0.2) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — |

| Rheumatologic chronic disease | 2 (2.7) | 9/1,240 (0.7) | .124 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (2.7) | 24 (1.9) | .650 | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | .494 |

| Depressive syndrome | 2/73 (2.7) | 13/1,229 (1.1) | .204 | 2 (5.3) | 0/35 (0.0) | .494 |

| Current pregnancy characteristics: | ||||||

| Multiple gestation | 6 (8.1) | 19 (1.5) | .002 a | 3 (7.9) | 3 (8.3) | 1.000 |

| Hemoglobin <10 g/dL | 2 (2.7) | 58/1,234 (4.7) | .575 | 1/37 (2.7) | 1 (2.8) | 1.000 |

| Platelets <100,000/μL | 1/71 (1.4) | 11/1,222 (0.9) | .494 | 0/37 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | .493 |

| Pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders | 11 (14.9) | 39 (3.1) | <.001 a | 1 (2.6) | 10 (27.8) | .002 b |

| Gestational diabetes | 10 (13.5) | 87/1,235 (7.0) | .039 a | 6 (15.8) | 4 (11.1) | .737 |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 3/71 (4.2) | 45/1,219 (3.7) | .744 | 0/36 (0.0) | 3/35 (8.6) | .115 |

| High risk of preeclampsia in screening | 12/63 (19.0) | 57/1,086 (5.2) | <.001 a | 2/31 (6.5) | 10/32 (31.3) | .012b |

Note: Data shown as number (percentage of total) unless otherwise indicated. BMI = body mass index; IVF = in vitro fertilization.

P<.05, IVF vs. spontaneous pregnancy.

P<.05, donor vs. own oocyte

Current smokers and ex-smokers

In addition, patients who achieved pregnancy with ART were more likely to be white (89.2% vs. 56.6% of spontaneous conception, P<.001), nulliparous (52.7% vs. 37.9%, P =.011), and were more often diagnosed with thrombophilia (10.8% vs. 1.4%, P<.001), without differences between those using own or donated oocytes (Table 2).

According to the current pregnancy history (Table 2), the IVF mothers had significantly more multiple pregnancies (8.1% vs. 1.5% of spontaneous conception patients, P=.002) and high risk screening of preeclampsia (19.0% vs. 5.2%, P<.001), which was especially remarkable in the IVF oocyte donor group (31.3% vs. 6.5% of the own oocyte group, P =.012). In addition, IVF patients had a higher risk of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders (14.9% vs. 3.1% of spontaneous conception patients, P =.001), attributable to the IVF oocyte donor group (27.8% vs. 2.6% of the own oocyte group, P =.002).

Perinatal and neonatal outcomes are described in Table 3 . Labor was induced in 55.4% and 36.5% of the IVF and spontaneous pregnancy patients, respectively. On the other hand, and although the operative delivery (operative vaginal and cesarean section) rate was high in all COVID-19 patients (515/1,347; 38.2%), it was in the IVF group that the operative approach corresponded to up to 73.0% of deliveries (compared with 36.2% of the spontaneous conception group). In addition, cesarean section was the most frequent method of delivery in the IVF group (55.4% vs. 26.1% of the spontaneous conception group; aOR 4.25, 95% CI 2.40–7.54; P<.001). Table 4 summarizes birth attendance in IVF and spontaneous pregnancies on the basis of the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cesarean section rates because of COVID-19 severe disease (pneumonia and complicated pneumonia) were similar between IVF and spontaneous pregnancies (P = 1.000 and P =1.000, respectively). However, cesarean sections because of induction failure were significantly more frequent in the ART group compared with the spontaneous conception group, overall (aOR 2.79, 95% CI 1.39–5.67, P =.004) and regardless of the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Table 3.

Perinatal and neonatal data of the study participants.

| All patients (n = 1,347) |

IVF patients: N = 74 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVF pregnancies (n = 74) | Spontaneous pregnancies (n = 1,273) | Adjusted P value | aOR (95% CI) | Own oocyte N = 38 | Donor oocytes N = 36 | Adjusted P value | |

| Perinatal outcomes | |||||||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks + days; mean/range) | 38+1 (26–41) | 38+5 (23–42) | .152 b | 38+6 (26–41) | 37+2 (27–41) | .013 a,b | |

| Onset of labor | |||||||

| Programmed C-section | 10 (13.5) | 132 (10.4) | 6 (15.8) | 4 (11.1) | |||

| Spontaneous | 23 (31.1) | 676 (53.1) | .227 c | 13 (34.2) | 10 (27.8) | .514 c | |

| Induced | 41 (55.4) | 465 (36.5) | .321 c | 19 (50.0) | 22 (61.1) | .161 c | |

| Type of delivery | |||||||

| Vaginal | 20 (27.0) | 812 (63.8) | 10 (26.3) | 10 (27.8) | |||

| Operative vaginal | 13 (17.6) | 129 (10.1) | <.001 a,d | 3.89 (1.83–8.26) | 9 (23.7) | 4 (11.1) | .197 d |

| Cesarean | 41 (55.4) | 332 (26.1) | <.001 a,d | 4.25 (2.40–7.54) | 19 (50.0) | 22 (61.1) | .499 d |

| Reason for Cesarean | |||||||

| Before labor e | 9/41 (22.0) | 115/332 (34.6) | 6/19 (31.6) | 3/22 (16.3) | |||

| Induction failure | 23/41 (56.1) | 107/332 (32.2) | 8/19 (42.1) | 15/22 (68.2) | |||

| During 1st and 2nd stage of labor | 6/41 (14.6) | 86/332 (25.9) | 5/19 (26.39) | 1/22 (4.5) | |||

| Severe COVID-19 | 3/41 (7.3) | 24/332 (7.2) | 0/19 (0.0) | 3/22 (13.6) | |||

| Preterm deliveries (<37 weeks of gestational age) | 12 (16.2) | 137 (10.8) | .221 | 2 (5.3) | 10 (27.8) | .004a | |

| Spontaneous delivery | 6/12 (50.0) | 72/137 (52.6) | 2/2 (100.0) | 4/10 (40.0) | |||

| Iatrogenic delivery | 6/12 (50.0) | 65/137 (47.4) | 0/2 (0.0) | 6/10 (60.0) | |||

| PROM | 15 (20.3) | 194 (15.2) | .534 | 8 (21.1) | 7 (19.4) | .517 | |

| PPROM | 4 (5.4) | 33 (2.6) | .424 | 1 (2.6) | 3 (8.3) | .132 | |

| Medical complications | |||||||

| Thromboembolic events: | 2 (2.7) | 12 (0.9) | .354 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | .970 | |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 2 (2.7) | 5 (0.4) | .129 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.8) | .970 | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (1.4) | 9 (0.7) | .624 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | .998 | |

| Admitted to ICU f | 6 (8.1) | 30 (2.4) | .014a | 3.62 (1.20–9.69) | 1 (2.6) | 5 (13.9) | .114 |

| Invasive ventilation | 3 (4.1) | 14 (1.1) | .021a | 5.64 (1.11–23.14) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.3) | .996 |

| Obstetric complications | |||||||

| Hemorrhagic events | 5 (6.8) | 66 (5.2) | .879 | 3 (7.9) | 2 (5.6) | .233 | |

| Abruptio placentae | 0 (0.0) | 12 (0.9) | .991 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 5 (6.8) | 56 (4.4) | .768 | 3 (7.9) | 2 (5.6) | .233 | |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 2 (2.7) | 2 (0.2) | .048a | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.6) | .997 | |

| Gestational hypertensive disorders | 12 (16.2) | 57 (4.5) | <.001a | 5.31 (2.45–10.93) | 4 (10.5) | 8 (22.2) | .060 |

| Moderate preeclampsia | 8 (10.8) | 33 (2.6) | <.001a | 5.90 (2.27–14.14) | 4 (10.5) | 4 (11.1) | .353 |

| Severe preeclampsia | 4 (5.4) | 24 (1.9) | .030a | 3.72 (1.00–11.30) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.1) | .996 |

| Stillbirth | 0 (0.0) | 10 (0.8) | .991 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | |

| Maternal mortality | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | .998 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | |

| Neonatal data | |||||||

| Apgar 5 score <7 | 1 (1.4) | 12/1,253 (1.0) | .554 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | .998 | |

| Umbilical artery pH <7.10 | 1 (1.8) | 33/1,018 (3.2) | .532 | 1/29 (3.4) | 0/28 (0.0) | .998 | |

| Admitted in NICU | 10 (13.5) | 127 (10.0) | .289 | 3 (7.9) | 7 (19.4) | .417 | |

| Neonatal mortality | 1 (1.4) | 5 (0.4) | .050 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | .998 | |

Note: Data shown as number (percentage of total) unless otherwise indicated. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit; IVF = in vitro fertilization; PPROM = preterm prelabor rupture of membranes; PROM = prelabor rupture of membranes.

Statistically significant differences, adjusted odds ratio (aOR), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated, controlling for maternal age and clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection (asymptomatic and symptomatic).

Linear regression model.

Multinomial logistic regression model, reference category is “programmed C-section”.

Multinomial logistic regression model, reference category is “vaginal delivery”.

Programmed C-section and mother election.

Before or after delivery.

Table 4.

Description of onset of labor, type of labor, and reasons for cesarean section categorized by the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in IVF and spontaneous pregnancies.

| IVF pregnancies (n = 74) |

Spontaneous pregnancies (n =1,273) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic |

Mild-moderate symptoms |

Pneumonia |

Complicated pneumonia a |

Asymptomatic |

Mild-moderate symptoms |

Pneumonia |

Complicated pneumonia a |

|

| n= 32 | (n = 33) | (n = 6) | (n = 3) | (n = 656) | (n = 434) | (n = 160) | (n = 23) | |

| Onset of labor: | ||||||||

| Programmed C-section | 2 (6.2) | 6 (18.2) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (33.3) | 49 (7.5) | 45 (10.4) | 26 (16.2) | 12 (52.2) |

| Spontaneous | 12 (37.5) | 9 (27.3) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 376 (57.3) | 226 (52.1) | 70 (43.8) | 4 (17.4) |

| Induced | 18 (56.2) | 18 (54.5) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (66.7) | 231 (35.2) | 163 (37.6) | 64 (40.0) | 7 (30.4) |

| Type of delivery: | ||||||||

| Vaginal | 11 (34.4) | 9 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 441 (67.2) | 274 (63.1) | 94 (58.8) | 3 (13.0) |

| Operative vaginal | 5 (15.6) | 7 (21.2) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 73 (11.1) | 46 (10.6) | 9 (5.6) | 1 (4.3) |

| C-section | 16 (50.0) | 17 (51.5) | 5 (83.3) | 3 (100) | 142 (21.6) | 114 (26.3) | 57 (35.6) | 19 (82.6) |

| Reasons for C-section: | ||||||||

| Before labor b | 2/16 (12.5) | 6/17 (35.5) | 1/5 (20.0) | 0/3 (0.0) | 50/142 (35.2) | 46/114 (40.4) | 17/57 (29.8) | 2/19 (10.5) |

| Induction failure | 10/16 (62.5) | 9/17 (52.9) | 3/5 (60.0) | 1/3 (33.3) | 52/142 (36.6) | 37/114 (32.5) | 16/57 (28.1) | 2/19 (10.5) |

| During 1st and 2nd stage of labor | 4/16 (25.0) | 2/17 (11.8) | 0/5 (0.0) | 0/3 (0.0) | 40/142 (28.2) | 31/114 (27.2) | 14/57 (24.6) | 1/19 (5.3) |

| Severe COVID-19 | 0/16 (0.0) | 0/17 (0.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | 2/3 (66.7) | 0/142 (0.0) | 0/114 (0.0) | 10/57 (17.5) | 14/19 (73.7) |

Note: C-section = cesarean section; IVF = in vitro fertilization.

with ICU admission and/or mechanical ventilation and/or septic shock

Programmed C-section and mother election

Analyzing the deliveries according to the waves of high incidence of SARS-CoV-2, we noted that the rate of cesarean sections in IVF mothers was higher during the first wave (57.8% vs. 40.0% in the second wave, P<.001); in the case of spontaneous pregnancies, a decrease was additionally observed (27.3% vs. 22.7% in the second wave), but this difference was not statistically significant.

IVF mothers experienced significantly more gestational hypertensive disorders (16.2% vs. 4.5% of spontaneous conception mothers; aOR 5.31, 2.45–10.93; P<.001), both in moderate and severe preeclampsia (Table 3), regardless of the origin of the oocytes. Besides, 21.4% of the women with symptomatic COVID-19 and IVF pregnancies developed preeclampsia (9/42, where 3/9 correspond to complicated pneumonia cases) compared with 4.5% of the women with symptomatic COVID-19 and spontaneous pregnancies (28/617) (P< .001).

In relation to ICU admission, 36 of the 1,347 women included in the study (2.67%) needed intensive care before or after delivery; of those, 30 of 1,273 (2.4%) belonged to the natural conception group and 6 of 74 (8.1%) to the ART group (P =.014). Therefore, a higher risk of ICU admittance was observed in IVF patients as well as a greater need for invasive ventilation (4.1% vs. 1.1% of spontaneous conception patients; P =.021) (Table 3). However, when this analysis was adjusted for gestational hypertensive disorders as well, the association of the type of conception and ICU admittance ceased to be significant (aOR 1.88, 0.55–5.62), being the risk of ICU admittance associated to preeclampsia (moderate and severe) (aOR 11.82, 5.25–25.87, P<.001) and the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection (aOR 8.74, 3.37–29.89). The event rate of invasive ventilations did not allow the previous verification without overfitting the model (21).

Thromboembolic and hemorrhagic events, stillbirth, and maternal mortality were similar for the two conception groups. In our series of deliveries in women with SARS-CoV-2-positive results, we recorded 2 maternal deaths (2/1,347; 0.15%).

There were no significant between-group differences in neonatal outcomes; a total of 6 neonatal deaths were reported (6/1,347, 0.44%). Five of these deaths corresponded to preterm neonates (1/5: mother with abruptio placentae and postpartum hemorrhage; 1/5: mother with complicated pneumonia and neonate with hyaline membrane disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, and encephalopathy; 1/5: fetal malformation, tetralogy of Fallot) and 1 term neonate (with fetal malformation).

Discussion

Our study provided information on the delivery care and prognosis of SARS-CoV-2 infected mothers and their newborns, in pregnancies achieved after ART (own or donor oocyte) compared with spontaneous conceptions. The main strength of the study was the large cohort of SARS-CoV-2-positive deliveries (1,347 from 78 centers across Spain), and the considerable quantity of ART pregnancies (74, 5.4%) included. Furthermore, and to our knowledge, no previous studies have analyzed the perinatal outcomes of mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2 with regard to the type of conception. In addition, our study considered separately within the IVF group those pregnancies achieved from own oocyte and those reached with donor oocyte, where the latter represented up to 48.6% of our ART pregnancies.

No differences were observed between the IVF and spontaneous conception groups in the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or the severity of symptoms, despite the older age of the IVF patients. Although COVID-19 has shown a more aggressive course in older patients (22), pregnant women are still considered young (<50 years) for this prognosis. Therefore, IVF pregnancy does not represent an increased risk of symptomatic infection, regardless of the oocyte origin, among pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2.

One of the most striking results of our study was the high frequency of induced labors and operative deliveries (operative vaginal and cesarean section) among these SARS-CoV-2-positive mothers, especially in the IVF group, in which cesarean sections reached up to 55.4% of deliveries (61.1% in those with donor eggs), and 56.1% of them were because of induction failure. The risk of cesarean section in IVF pregnancies and, in particular in women who were induced, has increased in the COVID-19 pandemic (23). Maternal disease could explain the need to end the pregnancy, leading to more inductions and cesarean sections. However, the cesarean section rates because of COVID-19 severe disease (pneumonia and complicated pneumonia) were similar between the IVF and spontaneous pregnancy groups. Therefore, this high operative delivery rate could be explained by maternal and obstetrician’s preferences, probably related to the uncertainty resulting from this new COVID-19 scenario. However, it is important to highlight that cesarean sections in pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection represented an independent factor of increased risk of maternal clinical deterioration (24), and therefore a in-depth risk-benefit assessment should be made before a cesarean section is performed.

We fortunately noticed a reduction in the rate of cesarean sections in IVF mothers between the first and second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (57.8% vs. 40%), which could be the result of medical awareness of this risk. However, it was still higher than figures recommended by the World Health Organization (25), and efforts should be made to keep reducing cesarean section rates in the actual pandemic.

On the other hand, the risk of preeclampsia in all its forms was higher in IVF mothers (especially in those with donor eggs), irrespective of maternal age and clinical presentation of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. In accordance with data published by multiple investigators in series before the COVID-19 pandemic, obstetric morbidity was increased in IVF mothers because of hypertension, thrombophilia, and other conditions (10, 11, 12, 13). This hypertension has been described as a risk factor of worse COVID-19 prognosis (26). Special attention must be paid to these IVF patients because of the association observed between COVID-19 symptoms and the development of preeclampsia, where a synergistic effect of both factors should not be ruled out (27, 28).

As a limitation of this study, it should be highlighted that symptomatic patients were over-represented in our study population because not all participating hospitals had a universal antenatal screening program for SARS-CoV-2 infection (so only identified symptomatic cases by passive surveillance) or implemented the program later. Moreover, the small number of ART pregnancies (n = 74) may have penalized the power of analyses, especially when comparing within the IVF group autologous and donor eggs. Finally, more robust studies comparing IVF patients with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection are needed, to establish the real effect of the virus in terms of perinatal and obstetric results in this group of patients.

Even so, our results are clinically relevant, because we do not know how long the pandemic will last, and ART techniques are indispensable given that “Reproductive care is essential for the well-being of the society and for sustaining birth rates at a time that many nations are experiencing declines” (29), added to the potential reduction of birth rates as a result of the social consequences of this pandemic.

Conclusions

High rates of operative delivery in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 were observed, not because of severe COVID-19, but probably related to maternal and obstetrician’s preferences, especially in IVF pregnancies. The method of conception did not affect the fetal or maternal outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infected women when controlling for maternal age and the clinical presentation of infection, except for preeclampsia occurrence.

Acknowledgments

The investigators thank José Montes (Office Research) for his support in organizing, cleansing, and analyzing the database, and Ana Royuela Vicente (Biostatistics Unit, Puerta de Hierro Biomedical Research Institute, IDIPHISA-CIBERESP) for her scientific advice. The Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group: María Belén Garrido Luque (Hospital Axarquia), Camino Fernández Fernández (Complejo Asistencial de León), Ana Villalba Yarza (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca), Esther María Canedo Carballeira (Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña), María Begoña Dueñas Carazo (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela), Rosario Redondo Aguilar (Complejo Hospitalario Jaén), Ángeles Sánchez-Vegazo García (Complejo Hospitalario San Millán - San Pedro de la Rioja), Esther Álvarez Silvares (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense), María Isabel Pardo Pumar (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra), Macarena Alférez Álvarez-Mallo (HM Hospitales), Víctor Muñoz Carmona (Hospital Alto Guadalquivir, Andújar), Noelia Pérez Pérez (Hospital Clínico San Carlos), Cristina Álvarez Colomo (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid), Onofre Alomar Mateu (Hospital Comarcal d’Inca), Claudio Marañon Di Leo (Hospital Costa del Sol), María del Carmen Parada Millán (Hospital da Barbanza), Adrián Martín García (Hospital de Burgos), José Navarrina Martínez (Hospital de Donostia), Anna Mundó Fornell (Hospital Universitario Santa Creu i Sant Pau), Elena Pascual Salvador (Hospital de Minas de Riotinto), Tania Manrique Gómez (Hospital de Montilla y Quirón Salud Córdoba), Marta Ruth Meca Casbas (Hospital de Poniente), Noemí Freixas Grimalt (Hospital Universitari Son Llàtzer), Adriana Aquise and María del Mar Gil (Hospital de Torrejón), Eduardo Cazorla Amorós (Hospital de Torrevieja), Alberto Armijo Sánchez (Hospital de Valme), María Isabel Conca Rodero (Hospital de Vinalopó), Ana Belén Oreja Cuesta (Hospital del Tajo), Cristina Ruiz Aguilar (Hospital Doctor Peset, Valencia), Susana Fernández García (Hospital General de L’Hospitalet), Mercedes Ramírez Gómez (Hospital General La Mancha Centro), Esther Vanessa Aguilar Galán (Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real), Rocío López Pérez (Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena), Carmen Baena Luque (Hospital Infanta Margarita de Cabra), Luz María Jiménez Losa (Hospital Infanta Sofía), Susana Soldevilla Pérez (Hospital Jerez de la Frontera), María Reyes Granell Escobar (Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez), Manuel Domínguez González (Hospital La Línea), Flora Navarro Blaya (Hospital Universitario Rafael Méndez), Juan Carlos Wizner de Alva (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara), Rosa Pedró Carulla (Hospital Sant Joan de Reus), Encarnación Carmona Sánchez (Hospital Santa Ana. Motril), Judit Canet Rodríguez (Hospital Santa Caterina de Salt), Eva Morán Antolín (Hospital Son Espases), Montse Macià (Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova), Laia Pratcorona (Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol), Irene Gastaca Abásolo (Hospital Universitario Araba), Begoña Martínez Borde (Hospital Universitario de Bilbao), Óscar Vaquerizo Ruiz (Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes), José Ruiz Aragón (Hospital Universitario de Ceuta), Raquel González Seoane (Hospital Universitario de Ferrol), María Teulón González (Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada), Lourdes Martín González (Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona), Cristina Lesmes Heredia (Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí de Sabadell), J. Román Broullón Molanes (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz), María Joaquina Gimeno Gimeno (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía), Alma María Posadas San Juan (Hospital Universitario Río Hortega), Otilia González Vanegas (Hospital Universitario San Cecilio, Instituto de Investigación Biosanitaria, Granada), Ana María Fernández Alonso (Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas), Lucía Díaz Meca (Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia), Alberto Puerta Prieto (Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves, Instituto de Investigación Biosanitaria, Granada), María del Pilar Guadix Martín (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena), Carmen María Orizales Lago (Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa, Leganés), José Antonio Sainz Bueno (Hospital Viamed, Grupo Chacón), Mónica Catalina Coello (Hospital Virgen Concha de Zamora), María José Núñez Valera (Hospital Virgen de la Luz), Lucas Cerrillos González (Hospital Virgen del Rocío), José Adanez García (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias), Elena Ferriols-Pérez (Hospital del Mar), Marta Roqueta (Hospital Universitario Dr. Josep Trueta), María Begoña Encinas Pardilla (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro), Marta García Sánchez (Hospital Universitario Quirónsalud de Málaga), Laura González Rodríguez (Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro de Vigo), Pilar Pintado Recarte (Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón), Elena Pintado Paredes (Hospital Universitario de Getafe), Paola Carmona Payán (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre), Yosu Franco Iriarte (Hospital Ruber Internacional, Madrid), and Luis San Frutos Llorente (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro).

Footnotes

V.E.C. has nothing to disclose. S.C.M. has nothing to disclose. A.A.S. has nothing to disclose. L.F.A. has nothing to disclose. A.S.M. has nothing to disclose. P.P.R. has nothing to disclose. C.C.M has nothing to disclose. B.M.P. has nothing to disclose. P.G.D.B.F. has nothing to disclose. O.N.V. has nothing to disclose. M.L.d.l.C.C. has nothing to disclose. O.M.P has nothing to disclose. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Supported by public funds obtained in competitive calls: grant COV20/00021 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III - Spanish Ministry of Health, and co-financed with Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) funds.

A list of the Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group collaborators appears in the Acknowledgments section.

Contributor Information

Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group:

María Belén Garrido Luque, Camino Fernández Fernández, Ana Villalba Yarza, Esther María Canedo Carballeira, María Begoña Dueñas Carazo, Rosario Redondo Aguilar, Ángeles Sánchez-Vegazo García, Esther Álvarez Silvares, María Isabel Pardo Pumar, Macarena Alférez Álvarez-Mallo, Víctor Muñoz Carmona, Noelia Pérez Pérez, Cristina Álvarez Colomo, Onofre Alomar Mateu, Claudio Marañon Di Leo, María del Carmen Parada Millán, Adrián Martín García, José Navarrina Martínez, Anna Mundó Fornell, Elena Pascual Salvador, Tania Manrique Gómez, Marta Ruth Meca Casbas, Noemí Freixas Grimalt, Adriana Aquise, María del Mar Gil, Eduardo Cazorla Amorós, Alberto Armijo Sánchez, María Isabel Conca Rodero, Ana Belén Oreja Cuesta, Cristina Ruiz Aguilar, Susana Fernández García, Mercedes Ramírez Gómez, Esther Vanessa Aguilar Galán, Rocío López Pérez, Carmen Baena Luque, Luz María Jiménez Losa, Susana Soldevilla Pérez, María Reyes Granell Escobar, Manuel Domínguez González, Flora Navarro Blaya, Juan Carlos Wizner de Alva, Rosa Pedró Carulla, Encarnación Carmona Sánchez, Judit Canet Rodríguez, Eva Morán Antolín, Montse Macià, Laia Pratcorona, Irene Gastaca Abásolo, Begoña Martínez Borde, Óscar Vaquerizo Ruiz, José Ruiz Aragón, Raquel González Seoane, María Teulón González, Lourdes Martín González, Cristina Lesmes Heredia, J. Román Broullón Molanes, María Joaquina Gimeno Gimeno, Alma María Posadas San Juan, Otilia González Vanegas, Ana María Fernández Alonso, Lucía Díaz Meca, Alberto Puerta Prieto, María del Pilar Guadix Martín, Carmen María Orizales Lago, José Antonio Sainz Bueno, Mónica Catalina Coello, María José Núñez Valera, Lucas Cerrillos González, José Adanez García, Elena Ferriols-Pérez, Marta Roqueta, María Begoña Encinas Pardilla, Marta García Sánchez, Laura González Rodríguez, Pilar Pintado Recarte, Elena Pintado Paredes, Paola Carmona Payán, Yosu Franco Iriarte, and Luis San Frutos Llorente

Supplementary data

Supplemental Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study data.

List of hospitals included in the study (n=78).

STROBE Statement—checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies.

References

- 1.World Health Organization coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI0bPAdSh6gIVyoKyCh0u9A2mEAAYASAAEgJjsvD_BwE Available at:

- 2.Mehta N., Chen K., Hardy E., Powrie R. Respiratory disease in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maxwell C., McGeer A., Tai K.F.Y., Sermer M. No. 225-management guidelines for obstetric patients and neonates born to mothers with suspected or probable severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e130–e137. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaigham M., Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: a systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:823–829. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S., Liao E., Cao D., Gao Y., Sun G., Shao Y. Clinical analysis of pregnant women with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1556–1561. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz D.A. An analysis of 38 pregnant women with COVID-19, their newborn infants, and maternal-fetal transmission of SARS-CoV-2: maternal coronavirus infections and pregnancy outcomes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144:799–805. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0901-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zambrano L.D., Ellington S., Strid P., Galang R.R., Oduyebo T., Tong V.T. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status—United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1641–1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez Perez O., Prats Rodriguez P., Munner Hernandez M., Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group The association between COVID-19 and preterm delivery: a cohort study with multivariate analysis. medRxiv. 2020;21:273. doi: 10.1101/2020.09.05.20188458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magli C. New generation embryos. ESHRE 2014;28–31. https://eshre.eu Available at:

- 10.Woo I., Hindoyan R., Landay M., et al. Perinatal outcomes after natural conception versus in vitro fertilization (IVF) in gestational surrogates: a model to evaluate IVF treatment versus maternal effects. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:993–998. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen V.M., Wilson R.D., Cheung A. Genetics Committee; Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Committee. Pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive technology. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28:220–233. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Genetics, U.S. Food and Drug Administration Committee on Obstetric Practice; Committee on Genetics; U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Committee opinion no 671: perinatal risks associated with assisted reproductive technology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e61–e68. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pandey S., Shetty A., Hamilton M., Bhattacharya S., Maheshwari A. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in singleton pregnancies resulting from IVF/ICSI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:485–503. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Encinas Pardilla M.B., Caño Aguilar Á., Marcos Puig B., Sanz Lorenzana A., Rodríguez de la Torre I., Hernando López de la Manzanara P., et al. Spanish registry of Covid-19 screening in asymptomatic pregnants. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2020;94 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puerta de Hierro University Hospital Protocol Record 55/20, Spanish Registry of Pregnant Women with COVID-19, NCT04558996. ClinicalTrials.gov; 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ Available at:

- 16.Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias Sanitarias. de Sanidad Ministerio, de España Gobierno. Actualización no 239. Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19). 29.10.2020. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_239_COVID-19.pdf Available at:

- 17.American College of Gynecologists Prelabor rupture of membranes: ACOG Practice Bulletin, number 217. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e80–e97. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown M.A., Magee L.A., Kenny L.C., Karumanchi S.A., McCarthy F.P., Saito S., et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis, and management recommendations for international practice. Hypertension. 2018;72:24–43. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomson A.J., Royal College of gynaecologists Care of women presenting with suspected preterm prelabour rupture of membranes from 24(+0) weeks of gestation: Green-Top Guideline no73. BJOG. 2019;126:e152–e166. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peduzzi P., Concato J., Kemper E., Holford T.R., Feinstein A.R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun L.M., Lanes A., Kingdom J.C.P., Cao H., Kramer M., Wen S.W., et al. Intrapartum interventions for singleton pregnancies arising from assisted reproductive technologies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36:795–802. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martínez-Perez O., Vouga M., Cruz Melguizo S., et al. Association between mode of delivery among pregnant women with COVID-19 and maternal and neonatal outcomes in Spain. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324:296–299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Betran A.P., Torloni M.R., Zhang J.J., Gülmezoglu A.M. WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;123:667–670. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang S., Wang J., Liu F., Liu J., Cao G., Yang C., et al. COVID-19 patients with hypertension have more severe disease: a multicenter retrospective observational study. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:824–831. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-0485-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coronado-Arroyo J.C., Concepción-Zavaleta M.J., Zavaleta-Gutiérrez F.E., Concepción-Urteaga L.A. Is COVID-19 a risk factor for severe preeclampsia? Hospital experience in a developing country. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;256:502–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendoza M., Garcia-Ruiz I., Maiz N., Rodo C., Garcia-Manau P., Serrano B., et al. Pre-eclampsia-like syndrome induced by severe COVID-19: a prospective observational study. BJOG. 2020;127:1374–1380. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veiga A., Gianaroli L., Ory S., Horton M., Feinberg E., Penzias A. Assisted reproduction and COVID-19: A joint statement of ASRM, ESHRE and IFFS. Fertil Steril. 2020;114:484–485. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of hospitals included in the study (n=78).

STROBE Statement—checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies.