Abstract

Atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesions of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS) refers to an intermediate histologic category of thyroid nodules in The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Although the risk of malignancy in this category was originally cited as 5–15%, recent literature has suggested higher rates of related malignancy ranging from 38% to 55%. Malignant nodules warrant surgery with total thyroidectomy or thyroid lobectomy, whereas benign nodules can be observed or followed with serial ultrasounds (US) based on their imaging characteristics. The management of nodules with a cytopathologic diagnosis of AUS/FLUS can be difficult because theses nodules lie between the extremes of benign and malignant. The management options for such nodules include observation, repeat fine-needle aspiration, and surgery. The use of molecular genetics, the identification of suspicious US characteristics, and the recognition of additional clinical factors are all important in the development of an appropriate, tailored management approach. Institutional factors also play a crucial role.

Keywords: Atypia of undetermined significance, Bethesda category III, follicular lesion of undetermined significance, Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System, thyroid nodule

Introduction

Thyroid cancer is the most common form of endocrine malignancy.1,2 According to the American Cancer Society, approximately 52,890 new cases and 2180 deaths due to thyroid cancer were predicted in the USA in 2020.3 The most accurate and cost-effective diagnostic method of evaluating a suspected thyroid nodule is fine-needle aspiration (FNA).4,5 FNA is often performed with ultrasound (US) guidance. Approximately 7–15% of thyroid nodules are malignant.6

Since 2007, The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (TBSRTC) has been used increasingly with FNA to classify thyroid nodules. This system broadly classifies thyroid nodules into six categories (Table 1) stratified by risk of malignancy. Category III of TBSRTC signifies atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesions of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS), and remains controversial due to the highly variable results and associated risk of malignancy found across different institutions. Essentially, AUS/FLUS implies an intermediate histologic grade between the benign and malignant grades.7 This classification is further divided into six categories: architectural atypia, Hürthle cell aspirates, cytologic and architectural atypia, cytologic atypia, atypical lymphoid cells, and atypia not otherwise specified (NOS). Previously, there was an expected incidence of approximately 7% in all FNA samples. However, more recent studies have shown this incidence to be as high as 10–12%.7–9 Although AUS and FLUS are categorically analogous and do not refer to two distinct entities, it is worth mentioning that AUS/FLUS refers only to follicular lesions and cannot be applied if the cells within the FNA sample are of different cell origins (e.g., lymphoid and parafollicular), whereas AUS is more versatile. There is extensive variability within this diagnosis, which has an approximate reproducibility of only 50%, even among expert pathologists.10 Originally, AUS/FLUS was estimated to pose a 5–15% risk of malignancy in all samples.11 However, recent data have suggested that rates of malignancy may be as high as 38–55% for nodules with an initial diagnosis of AUS/FLUS.8,12 The variability and higher rates of malignancy posed by these lesions highlight both the uncertainty and the importance of managing them.5

Table 1.

Six categories of the thyroid nodules based on the 2017 Bethesda Classification.

| Category | Description | Risk of malignancy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | Nondiagnostic or unsatisfactory | 5–10 |

| II | Benign | 0–3 |

| III | Atypia of undetermined significance or follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AUS/FLUS) | 6–18 (10–30a) |

| IV | Follicular neoplasm or suspicious for a follicular neoplasm | 10–40 (25–40a) |

| V | Suspicious for malignancy | 45–60 (50–75a) |

| VI | Malignant | 94–96 (97–99a) |

aRisk of malignancy increased when, noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features is taken equivalent to carcinoma.

The management of lesions categorized by TBSRTC as either benign (II) or suspicious for malignancy/malignant (V–VI) is straightforward. Specifically, the management of these lesions involves observation or surgery, respectively, with the latter involving lobectomy or total thyroidectomy. However, Category IV (follicular neoplasm or suspicious for follicular neoplasm) is considered a more indeterminate category for which lobectomy is recommended in the proper clinical and sonographic contexts. Indeterminate lesions in Category III (AUS/FLUS) can be managed by a course of repeat FNA, molecular testing, and/or surgical resection (lobectomy or total thyroidectomy).7,13 While the American Thyroid Association (ATA) has provided various recommendations, the management of the AUS/FLUS is more variable and multifactorial compared to the management of other categories of lesions:2,14,15

Further evaluation with repeat FNA or molecular testing may be performed instead of proceeding directly with surveillance or surgery after the consideration of concerning clinical and US features for nodules with AUS/FLUS cytology. Informed patient preference and feasibility should be considered as part of the decision-making process.

Depending on clinical risk factors, US patterns, and patient preferences, management with surveillance or diagnostic surgical excision may be performed if repeat FNA cytology and/or molecular testing are not performed or are inconclusive.

A multimodal approach involving imaging characteristics, molecular genetics, and clinical factors contributes to management, as a greater understanding of these features can allow for a more organized management approach.

Molecular genetics

BRAF mutation

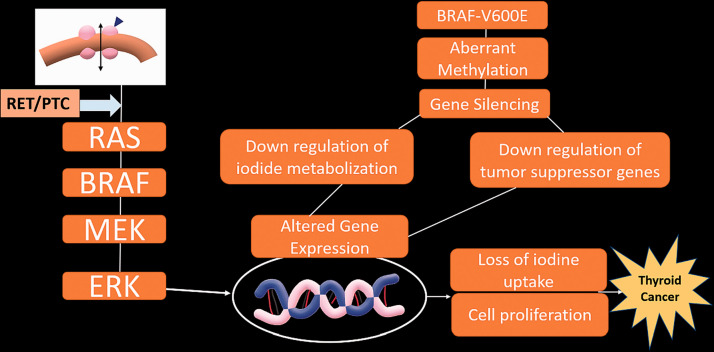

At least 60–70% of all thyroid cancers harbor one genetic mutation.16 The most commonly associated mutation is the BRAF (v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B) mutation, which affects the activation of mitogen-activated pathway kinases, resulting in an increase in the intensity of cellular proliferation, inhibition of differentiation and apoptosis, and a loss of control over the cell cycle (Figure 1).17

Figure 1.

Key genetic modifications and associated epigenetic alterations in thyroid cancer. RET: rearranged during transfection oncogene; PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma oncogene; BRAF: v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B; BRAFV600E: V600E mutation of BRAF; RAS: rat sarcoma gene; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase.

The BRAF mutation has been seen in up to 80% of cases of papillary thyroid cancer, which is the most common form of thyroid cancer, accounting for 85–90% of all cases of thyroid cancers.16,18 While this remains controversial, some studies have found this mutation to be associated with aggressive features, such as extrathyroidal extension, higher stages of cancer, lymph node metastasis, recurrence, and reduced overall survival rate.18,19 Given the high five-year survival rate for papillary cancer (95–97%), the statistically significant association of the BRAF mutation with aggressive features is important because it can otherwise be difficult to distinguish patients who need more aggressive treatment from those who do not.

Multiple studies have also demonstrated the utility of BRAF in the management of samples diagnosed with AUS/FLUS. The BRAF mutation has been associated with a higher likelihood ratio for the prediction of malignancy after an initial diagnosis of AUS/FLUS (positive BRAF600VE mutation: 97.5%, negative BRAF600VE mutation: 39.7%).12

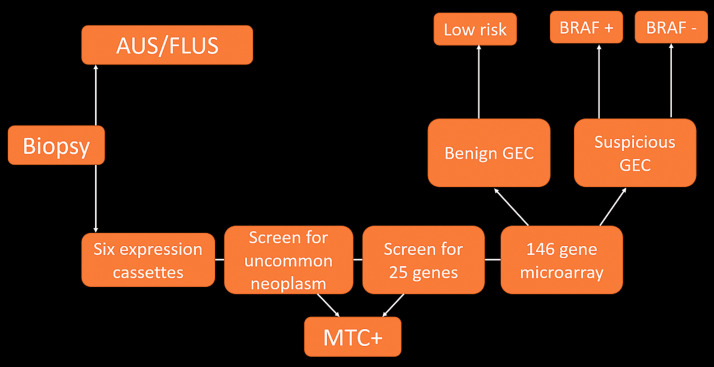

Gene expression classifiers

Recent developments have led to the commercial availability of gene expression classifiers (GEC). GECs are sets of molecular markers that can be applied to thyroid nodules that have been diagnosed as indeterminate following FNA (Figure 2). Although the estimated risk of malignancy in AUS/FLUS nodules varies across the literature, it is generally accepted that most AUS/FLUS nodules are benign. Due to the low cancer risk associated with these nodules, management recommendations for these nodules have generally been conservative. Repeating FNA has been suggested as the most appropriate follow-up method for AUS/FLUS nodules, along with the consideration of diagnostic lobectomy for nodules showing AUS/FLUS in the repeating FNA. Even with the implementation of this conservative management recommendation, a significant number of patients with indeterminate nodules undergo diagnostic surgery. In most of these cases, lobectomy reveals histologically benign nodules, and surgery may therefore be regarded as overtreatment. Molecular testing has thus emerged as a tool for further stratification of cytologically indeterminate nodules into clinically meaningful risk categories. The goal of molecular testing is to stratify thyroid nodules in indeterminate FNAs to prevent excessive and unnecessary surgical procedures.20

Figure 2.

Overview of the pathway and methodology of a gene expression classifier (GEC) following an indeterminate thyroid biopsy. AUS/FLUS: atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesions of undetermined significance; MTC: medullary thyroid carcinoma.

Four GEC tests are commercially available in the US: (a) the Afirma GEC (Ceracyte, Inc., South San Francisco, CA); (b) ThyroSeq v2 and v3 (CBL Path, Inc., Rye Brook, NY, and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA); (c) ThyGenX/ThyraMIB (Interpace Diagnostics, Inc., Parsippany, NJ); and (d) RosettaGX Reveal (Rosetta Genomics, Inc., Philadelphia, PA).20 Of these tests, the Afirma GEC and ThyroSeq are the most commonly used. The Afirma GEC measures the expression of 167 gene transcripts and reports results as “suspicious” or “benign” without determining the specific mutation. The original validation study of this test demonstrated a negative predictive value (NPV) of 95% in AUS/FLUS nodules.16 Several post-validation studies have shown that the Afirma GEC produces high NPVs and serves as a useful test to rule out malignancy.21–23 However, out of 74 cases with “suspicious” Afirma GEC results, only 28 were found to be malignant. Furthermore, the positive predictive value (PPV) of the test was only 38%, making it less attractive as a rule-in test.16 As a result, more than half of all patients who test positive on the Afirma GEC may still display benign disease in their surgical pathology results. ThyroSeq is a next-generation sequencing–based test that includes the gene mutations and fusions most commonly associated with thyroid cancer. The reported NPV of ThyroSeq in AUS/FLUS nodules is 97.2% for ThyroSeq V224 and 97% for ThyroSeq V3.25 Validation studies of ThyroSeq have reported PPVs of 76.9% for ThyroSeq V2 and 64% for ThyroSeq V3; these PPVs are higher than that of the Afirma GEC. ThyroSeq results are more informative because they provide information regarding specific mutations. Certain mutations, such as the BRAF600VE mutation, are associated with a very high risk of malignancy. The specific results and high NPV of ThyroSeq qualify it as a good rule-out test and as a potential rule-in test when certain mutations (e.g., the BRAF600VE mutation) are present. These tests require a dedicated pass to collect material into a vial. Rapid on-site evaluation by a cytologist should be available to determine whether sufficient material is obtained or whether more samples should be collected for the molecular tests to reduce the number of times at which the procedure must be repeated. While access to molecular tests varies by location and institution, these tests have been shown to decrease the number of unnecessary surgeries on patients.26 The cost of molecular tests may affect their utility as routine tests of AUS/FLUS nodules. One small study demonstrated that ThyroSeq is cost-effective compared to diagnostic thyroid surgery for the evaluation of AUS/FLUS nodules.27 However, more studies are needed before we can conclude that molecular tests are as cost-effective as routine tests for the management of indeterminate thyroid nodules.

Role of imaging

Suspicious imaging features are associated with an increased risk of malignancy, and may suggest that a more aggressive management approach should be taken for nodules categorized as indeterminate following biopsy. Repeat FNA is a common practice for the management of AUS/FLUS nodules. An absence of suspicious US features combined with less-than-suspicious findings of malignancy in repeat FNA following initial AUS/FLUS diagnosis without a BRAF mutation has been estimated to have NPVs >90%. This demonstrates the value of a combined approach including molecular testing and US imaging in the management of AUS/FLUS nodules.28

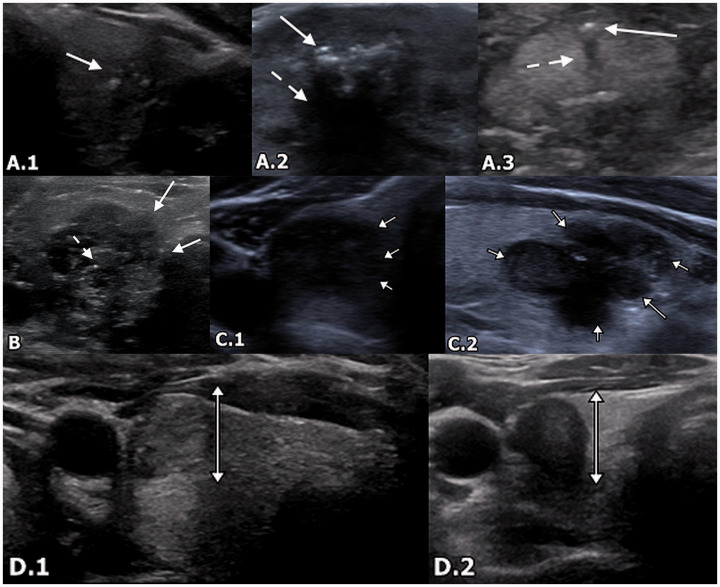

Suspicious US imaging features include (a) microcalcifications, (b) irregular margins, (c) hypoechogenicity (less than the surrounding strap musculature), and (d) taller-than-wide configuration (Figure 3).12,29,30 These are present in approximately 18–50% of cases of nodules with AUS/FLUS cytology, and may be associated with a malignancy rate of up to 79.3%. Conversely, the malignancy rate of nodules with indeterminate US imaging features can be as low as 24.7%.12 Microcalcifications and macrocalcifications, taller-than-wide configuration, and hypoechogenicity show higher odds ratios for malignancy than a lack of calcifications, round configuration, and hyperechogenicity. Notably, the presence of rim calcifications is not associated with significantly different odds ratios compared to a lack of calcifications. The presence of multiple suspicious features often correlates with Category 4 or 5 of the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS) classification system.30 The ATA further classifies nodules as high suspicion, intermediate suspicion, low suspicion, very low suspicion, or benign based on imaging features. Biopsy is recommended for high or intermediate suspicion nodules >1 cm and for low suspicion nodules >1.5 cm. Biopsy may also be considered for very low suspicion nodules, including spongiform nodules, that are >2 cm. However, biopsy does not need to be performed for benign lesions, such as benign cysts.2 Examples of pathology-proven malignancy with suspicious imaging features originally categorized as AUS/FLUS by initial FNA are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Suspicious imaging features on US. (a) 1: A 46-year-old woman with PTC. Transverse US demonstrates a cluster of microcalcifications (arrow) without posterior acoustic shadowing. (a) 2: A 71-year-old woman with a benign nodule following biopsy. Transverse US demonstrates macrocalcifications (arrow) with posterior acoustic shadowing (dotted arrow). (a) 3: A 70-year-old woman with a suspicious nodule that was shown to be stable over time. Transverse US demonstrates a microcalcification (arrow) with posterior acoustic shadowing (dotted arrow). (b) A 50-year-old female with PTC. Transverse US demonstrates lobulated and irregular margins (arrows). Additionally, there are microcalcifications (dotted arrow) and marked hypoechogenicity. (c) 1: A 60-year-old woman with nodule that was benign on biopsy. Transverse US demonstrates diffusely hypoechoic thyroid nodule with an irregular outline (arrows). (c) 2: A 38-year-old woman with multinodular hyperplastic thyroid and dominant adenomatoid nodule with cystic degeneration and Hürthle cell changes. Sagittal US demonstrates hypoechoic thyroid nodule with lobulated margins (arrows). (d) 1: A 32-year-old woman with PTC. Transverse US demonstrates a taller-than-wide configuration. (d) 2: A 40-year-old woman with PTC. Transverse US demonstrates a taller-than-wide configuration (brackets). Nodule is also hypoechoic. US: ultrasound; PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma.

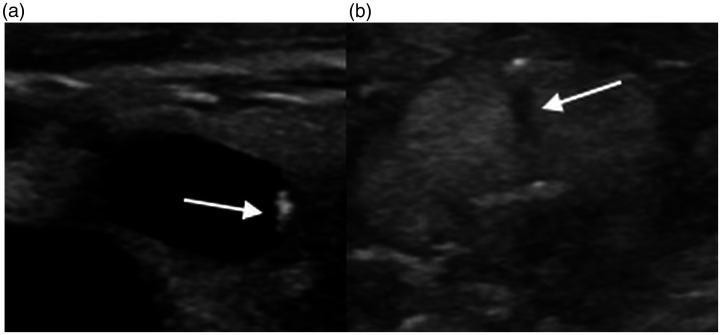

Figure 4.

(a) A 44-year-old woman found to have papillary malignancy after diagnosis of AUS/FLUS on initial biopsy. Transverse US demonstrates microcalcifications (arrow), taller-than-wide shape, and marked hypoechogenicity. (b) A 24-year-old woman found to have papillary malignancy after initial diagnosis of AUS/FLUS. Sagittal US demonstrates lobulated margins (dotted arrows) and microcalcifications (arrows).

An accurate interpretation of US findings is crucial to stratify risk and determine the next step of management. Pitfalls are common and can lead to misinterpretation of US findings. One common pitfall is mimicry of suspicious imaging characteristics that are not necessarily suggestive of malignancy. Awareness of this pitfall can reduce imaging overcalls and unnecessary biopsies.

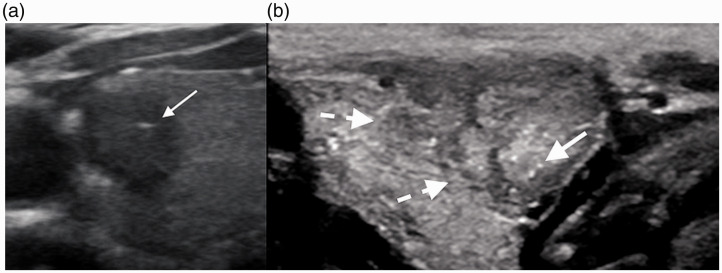

Calcifications versus colloids

Colloid crystals are commonly encountered in thyroid US images and are suggestive of a benign etiology. The most distinctive characteristic that differentiates colloid crystals from calcifications is the presence of a comet-tail artifact (Figure 5), characterized by a dense trail of tapering echoes caused by a reverberation artifact from dense colloid crystals. This contrasts with the posterior shadowing seen with some calcifications, although smaller echogenic foci may not be large enough to demonstrate shadowing.31–33 Colloid lesions are also often predominantly cystic and anechoic. In addition, colloid lesions are often associated with multiple lesions within the gland.34

Figure 5.

Pitfalls of imaging. (a) A 55-year-old woman with a colloid nodule. Transverse US shows an anechoic nodule with the comet-tail artifact (arrows). (b) A 70-year old woman with a benign thyroid nodule. Transverse US shows a focal calcification with showing posterior acoustic shadowing (arrows).

Partially cystic malignancy versus partially cystic benign nodules

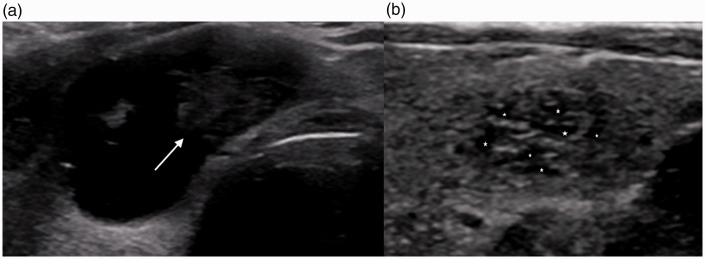

Although a solid lesion is more likely to be malignant, partially cystic lesions may represent either cystic papillary neoplasm or benign etiologies, the most common of the latter being spongiform nodules. Features that may indicate partially cystic malignancy include an eccentric configuration of the solid component (Figure 6), hypoechogenicity (of the solid component), irregular margins, and associated microcalcifications.35

Figure 6.

Pitfalls of imaging. (a) A 53-year-old-man with cystic PTC. Transverse US shows a mixed cystic and solid lesion with a left eccentric hypoechoic solid component (arrow). (b) A 62-year-old man with a benign nodule. Transverse US demonstrates a benign spongiform nodule with clustered microcysts (*) distributed throughout the nodule with smooth margins.

Spongiform lesions, which have a characteristic “honeycomb” or “puffy pastry” appearance, comprise one commonly encountered form of benign partially cystic nodules. Various studies have yielded different conclusions regarding the benignity of spongiform nodules because spongiform appearance varies by degree across different nodules.30 Previous studies have suggested that a spongiform appearance occupying >50% or the entirety of the nodule without hypervascularity is specific to benignity. A more recent study, which attempted to stratify the risk of malignancy based on the degree of spongiform material occupying the nodule, found no evidence of malignancy in which the spongiform appearance occupied >75% of the entire nodule. However, no definite correlation was found between the risk of malignancy and the amount of spongiform material.34 The nodules with sponge-like material that were found to be malignant possessed additional features suggestive of malignancy, such as microcalcifications and hypoechogenicity. Overall, the classification of a spongiform and/or partially cystic nodule as benign should be performed in the absence of any additional suspicious features. Findings that are suggestive of benignity include similarly sized microcysts (spongiform content), non-eccentric configuration of the solid component, thin echogenic septa, ovoid-to-round shape, colloid crystals, isoechogenicity, and smooth margins.34,35

Irregular versus ill-defined margins

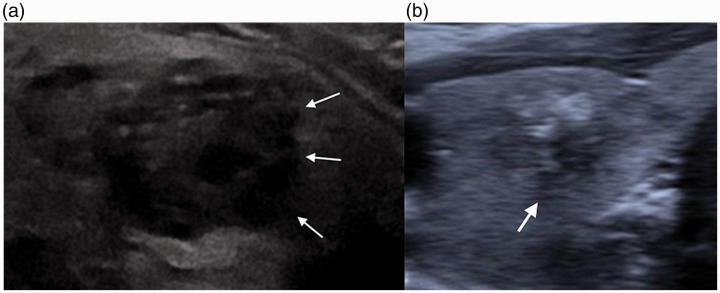

With regard to sonographic features, the differentiation between irregular and indistinct margins has been shown to have the highest intraobserver variability. Irregular margins include margins with microlobulated or spiculated contours. These margins are well defined, but often form acute angles with the surrounding parenchyma. In contrast, ill-defined margins are margins for which the exact border between the nodule and the normal thyroid parenchymal is difficult to discern. These findings are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Pitfalls of imaging. (a) A 57-year-old woman with suspicious thyroid nodule. Transverse US demonstrates hypoechoic thyroid nodule with irregular and lobulated but well-defined margins (arrows). Lesion is also hypoechoic with echogenic foci. (b) A 70-year-old woman with thyroid nodule stable over the past year. Transverse US demonstrates ill-defined margins (arrows) between the thyroid nodule and surrounding parenchyma.

Irregular margins are highly suggestive of malignancy, with high specificity values ranging from 83% to 91.8% and PPVs ranging from 60% to 81.3%. In contrast, ill-defined margins are not necessarily suggestive of malignancy, but are commonly seen in both malignant and benign nodules. It is worth noting that sensitivity can be improved by the use of high-resolution probes to delineate the margins, which can become more blurred in lower-resolution probes.36

Taller-than-wide shape

The taller-than-wide distinction refers to an anteroposterior dimension longer than the transverse dimension, implying that nodules should always be measured in the transverse plane rather than the sagittal plane. A nodule mistakenly measured as taller than wide in the wrong plane will likely result in an unnecessary FNA.

Avoiding pitfalls

Minimization of the aforementioned pitfalls is vital, given that each feature can likely change the TI-RADS classification and thus subsequent management. US is unique in that it relies more on the technologist (or sonographer) than other modalities for image quality and diagnosis. Therefore, sonographer education on the aforementioned pitfalls is a good starting point for ensuring that everyone is on the same page.37 Additionally, a dedicated cine clip of the area of interest is important for problem solving, as single still images are more likely to be misinterpreted.37 The use of a high-resolution probe, as mentioned above, is especially helpful for the evaluation of margins to differentiate between ill-defined and irregular margins. More direct ways in which a radiologist can avoid these pitfalls include the use of peer learning systems and double reading with a different radiologist in the department.37

Management of AUS/FLUS nodules

Institutional factors

The high rates of malignancy associated with AUS/FLUS and its varying prevalence rates noted across the literature (previously, 5–15%; more recently, up to 38–55%) highlight not only the prevalence of AUS/FLUS but also its underlying variations across institutions.8,10 Currently, various management practices are followed at different institutions for the management of indeterminate thyroid nodules. According to the 2015 ATA guidelines, the risk of malignancy should be independently defined at each institution to guide risk estimates and appropriate molecular testing.4 For example, lower institutional rates of malignancy in AUS/FLUS nodules may warrant a more conservative approach involving serial USs, while higher institutional rates of malignancy may warrant a more aggressive workup involving repeat FNA or surgery.

Patient demographics

Rates of AUS/FLUS diagnosis and malignancy vary widely across institutions, as does the patient population presenting with suspicious thyroid nodules. Various factors should be taken into account in the development of a workup, including pretest probability, family history, socioeconomic status, clinical symptoms, risk factors, and history of malignancy.4 The feasibility of the diagnostic test should also be considered, particularly with regard to molecular testing, given its associated costs.

A practical approach

The management of AUS/FLUS nodules remains controversial. One common approach is to repeat FNA in the presence of worrisome US features and high clinical suspicion. The threshold of suspicion should be low, given the higher rates of malignancy associated with AUS/FLUS than previously noted. Previously, the Bethesda recommendation was to wait three months after a nondiagnostic FNA sample to repeat the procedure.7 This recommendation was based on concerns regarding lowering diagnostic yield and increasing false-positives. A more recent study found no significant differences in diagnostic yield and accuracy related to the timing of repeat FNA, and concluded that repeat FNA could be performed as soon as necessary prior to three months. This conclusion is referenced in the 2015 ATA management guidelines.2,15 This could not only lead to earlier treatment but also considerably reduce stress on the patient by reducing the wait time for the repeat sample.38

If repeat FNA remains noncontributory, then a core biopsy can be obtained in place of FNA for repeat tissue sampling. Core needle biopsies provide better tissue samples. Specifically, previous studies have demonstrated that core needle biopsies are associated with lower rates of indeterminate biopsy results in repeat biopsies following initial indeterminate FNA results.39 One previous study found that the rate of nondiagnostic samples following core biopsy after indeterminate FNA was 1.8% (vs. 48.6% for FNA).40 A more recent study showed a lesser but significant difference in the rate of indeterminate samples with core needle biopsies (26.7% vs. 49.1% for FNA). No significant differences in complication rates were found between these methods.39 Core needle biopsy has also been shown to have greater sensitivity than FNA for the diagnosis of malignancy in repeat samples.39 A review of the cytopathology slides by a secondary pathologist can be considered before repeat FNA is scheduled. This may be performed more readily than repeat FNA because it comes at a much lower additional cost and can be accomplished more quickly.

As described above, optional testing for a panel of mutations should be considered in addition to testing for the BRAF mutation, which has been shown to have PPVs up to 100%. The body of evidence has demonstrated that the use of molecular tests with high NPVs significantly decreases unnecessary surgical procedures. When a high-risk mutation (e.g., the BRAF600VE mutation) is identified, the result can be used to guide surgical plans (e.g., thyroidectomy vs. lobectomy). Although there are some concerns about the costs and time required to obtain such results, it is our experience and recommendation that molecular tests have an advantage in the management of AUS/FLUS nodules by: (a) decreasing unnecessary surgical procedures, (b) avoiding repeat FNA, and (c) guiding surgical plans in certain situations. Finally, these tests may be cost-effective in the long run, as they may decrease surgical costs and prevent surgery-related complications.

Finally, surgery can be performed with lobectomy or total thyroidectomy, especially if clinical suspicion is high and tissue sampling or molecular testing is not contributory. However, this option should be decided upon only after deep introspection and clinical deliberation. This decision will usually depend on various clinical factors for high-risk patients. The institutional rates of malignancy detected in AUS/FLUS nodules should also be considered before a decision is made.

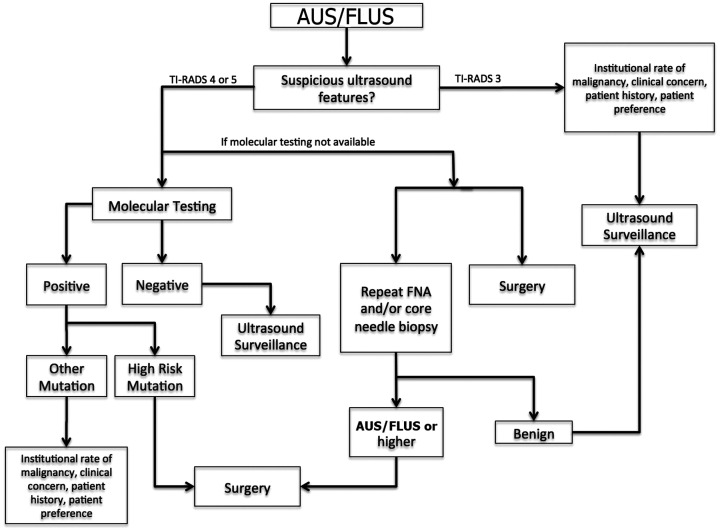

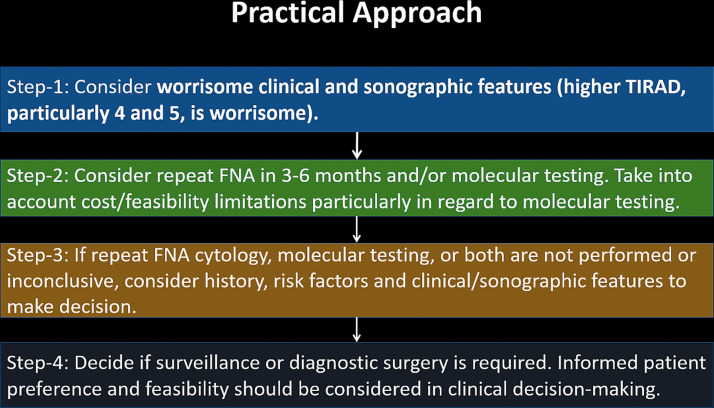

A broad sample algorithm and step-by-step approach are shown in Figures 8 and 9, respectively.

Figure 8.

Overview of AUS/FLUS. An algorithmic approach to an initial diagnosis of AUS/FLUS.

Figure 9.

Sample step-by-step approach to the management of nodules initially diagnosed as AUS/FLUS.

Conclusion

AUS/FLUS thyroid lesions comprise an intermediate pathologic grade for US-guided thyroid FNA without any definitive management recommendations and with higher rates of malignancy than previously thought. Such lesions may require a multimodal approach to management.

Suspicious imaging features, particularly TI-RADS 4 and 5 lesions, have been shown to have high PPVs for malignancy. When such features are present, a more aggressive approach should be considered. Molecular markers are becoming more widely used as well, with the BRAF mutation being highly indicative of malignancy. Molecular tests with high NPVs should be performed to target a panel of mutations when possible. The institutional rate of malignancy also varies widely and should be taken into consideration when deciding on management.

After an initial diagnosis of AUS/FLUS, the concurrently collected specimen should be sent for molecular testing if available. When molecular testing is not available, repeating FNA sooner than three months of first diagnosis of AUS/FLUS may lead to a quicker diagnosis and treatment and may also reduce stress to the patient. Alternative pathways include repeating sampling using core needle biopsy instead of FNA, obtaining a second opinion review by a different cytopathologist, and repeating sampling using excisional biopsy. These pathways should be considered based on institutional risk of malignancy as well as clinical and radiological features.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Neeraj Lalwani https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5514-2805

References

- 1.Nguyen QT, Lee EJ, Huang MG, et al . Diagnosis and treatment of patients with thyroid cancer. Am Health Drug Benefits 2015; 8: 30–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correa P, Chen VW. Endocrine gland cancer. Cancer 1995; 75: 338–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Thyroid Cancer, 2020. Available at: https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/#!/cancer-site/Thyroid

- 4.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016; 26: 1–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Çuhaci N, Arpaci D, Üçler R, et al. Malignancy rate of thyroid nodules defined as follicular lesion of undetermined significance and atypia of undetermined significance in thyroid cytopathology and its relation with ultrasonographic features. Endocr Pathol 2014; 25: 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao L-Y, Wang Y, Jiang Y-X, et al. Ultrasound is helpful to differentiate Bethesda class III thyroid nodules: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e6564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The 2017 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid 2017; 27: 1341–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg S, Naik LP, Kothari KS, et al. Evaluation of thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda category III on FNAC. J Cytol 2017; 34: 5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan PS, Hirschowitz SL, Fung PC, et al. The impact of atypia/follicular lesion of undetermined significance and repeat fine-needle aspiration: 5 years before and after implementation of the Bethesda System. Cancer Cytopathol 2014; 122: 866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho AS, Sarti EE, Jain KS, et al. Malignancy rate in thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda category III (AUS/FLUS). Thyroid 2014; 24: 832–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cibas ES, Ali SZ. and NCI Thyroid FNA State of the Science Conference. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol 2009; 132: 658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong SH, Hong HS, Lee EH, et al. Outcome of thyroid nodules characterized as atypia of undetermined significance or follicular lesion of undetermined significance and correlation with ultrasound features and BRAF(V600E) mutation analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 201: W854–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong S-H, Lee H, Cho M-S, et al. Malignancy risk and related factors of atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance in thyroid fine needle aspiration. Int J Endocrinol 2018; 2018: 4521984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin JH, Baek JH, Chung J, et al. Ultrasonography diagnosis and imaging-based management of thyroid nodules: revised Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology consensus statement and recommendations. Korean J Radiol 2016; 17: 370–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandra S, Chandra H, Bisht SS. Malignancy rate in thyroid nodules categorized as atypia of undetermined significance or follicular lesion of undetermined significance – an institutional experience. J Cytol 2017; 34: 144–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander EK, Kennedy GC, Baloch ZW, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of benign thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytology. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 705–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catalano MG, Fortunati N, Boccuzzi G. Epigenetics modifications and therapeutic prospects in human thyroid cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012; 3: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xing M, Alzahrani AS, Carson KA, et al. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA 2013; 309: 1493–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, Chen T, Liu Z. Associations between BRAF(V600E) and prognostic factors and poor outcomes in papillary thyroid carcinoma: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol 2016; 14: 241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishino M, Nikiforova M. Update on molecular testing for cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018; 142: 446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaudhary S, Hou Y, Shen R, et al. Impact of the Afirma gene expression classifier result on the surgical management of thyroid nodules with category III/IV cytology and its correlation with surgical outcome. Acta Cytol 2016; 60: 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samulski TD, LiVolsi VA, Wong LQ, et al. Usage trends and performance characteristics of a “gene expression classifier” in the management of thyroid nodules: an institutional experience. Diagn Cytopathol 2016; 44: 867–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baca SC, Wong KS, Strickland KC, et al. Qualifiers of atypia in the cytologic diagnosis of thyroid nodules are associated with different Afirma gene expression classifier results and clinical outcomes. Cancer Cytopathol 2017; 125: 313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Chiosea SI, et al. Impact of the multi-gene ThyroSeq next-generation sequencing assay on cancer diagnosis in thyroid nodules with atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance cytology. Thyroid 2015; 25: 1217–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steward DL, Carty SE, Sippel RS, et al. Performance of a multigene genomic classifier in thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytology: a prospective blinded multicenter study. JAMA Oncol 2019; 5: 204–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jug R, Parajuli S, Ahmadi S, et al. Negative results on thyroid molecular testing decrease rates of surgery for indeterminate thyroid nodules. Endocr Pathol 2019; 30: 134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivas AM, Nassar A, Zhang J, et al. ThyroSeq® v2.0 molecular testing: a cost-effective approach for the evaluation of indeterminate thyroid modules. Endocr Pract 2018; 24: 780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim TH, Jeong DJ, Hahn SY, et al. Triage of patients with AUS/FLUS on thyroid cytopathology: effectiveness of the multimodal diagnostic techniques. Cancer Med 2016; 5: 769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumbhar SS, O’Malley RB, Robinson TJ, et al. Why thyroid surgeons are frustrated with radiologists: lessons learned from pre- and postoperative US. Radiographics 2016; 36: 2141–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tessler FN, Middleton WD, Grant EG, et al. ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS): white paper of the ACR TI-RADS Committee. J Am Coll Radiol 2017; 14: 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim MJ, Kim EK, Kwak JY, et al. Differentiation of thyroid nodules with macrocalcifications: role of suspicious sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med 2008; 27: 1179–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Na DG, Kim DS, Kim SJ, et al. Thyroid nodules with isolated macrocalcification: malignancy risk and diagnostic efficacy of fine-needle aspiration and core needle biopsy. Ultrasonography 2016; 35: 212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taki S, Terahata S, Yamashita R, et al. Thyroid calcifications: sonographic patterns and incidence of cancer. Clin Imaging 2004; 28: 368–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JY, Jung SL, Kim MK, et al. Differentiation of benign and malignant thyroid nodules based on the proportion of sponge-like areas on ultrasonography: imaging-pathologic correlation. Ultrasonography 2015; 34: 304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park JM, Choi Y, Kwag HJ. Partially cystic thyroid nodules: ultrasound findings of malignancy. Korean J Radiol 2012; 13: 530–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anil G, Hegde A, Chong FH. Thyroid nodules: risk stratification for malignancy with ultrasound and guided biopsy. Cancer Imaging 2011; 11: 209–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tappouni RR, Itri JN, McQueen TS, et al. ACR TI-RADS: pitfalls, solutions, and future directions. Radiographics 2019; 39: 2040–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deniwar A, Hammad AY, Ali DB, et al. Optimal timing for a repeat fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodule following an initial nondiagnostic fine-needle aspiration. Am J Surg 2017; 213: 433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Na DG, Kim J-h, Sung JY, et al. Core-needle biopsy is more useful than repeat fine-needle aspiration in thyroid nodules read as nondiagnostic or atypia of undetermined significance by The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid 2012; 22: 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park KT, Ahn SH, Mo JH, et al. Role of core needle biopsy and ultrasonographic finding in management of indeterminate thyroid nodules. Head Neck 2011; 33: 160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]