Abstract

Scholarship on the health impacts of resource extraction displays prominent gaps and apparent corporate and neocolonial footprints that raise questions about how science is produced. We analyze production of knowledge, on the health impacts of mining, carried out in relation to the Canadian International Resources and Development Institute (CIRDI), a university-based organization with substantial extractive industry involvement and links to Canada’s mining-dominated foreign policy. We use a “political ecology of knowledge” framework to situate CIRDI in the context of neoliberal capitalism, neocolonial sustainable development discourses, and mining industry corporate social responsibility techniques. We then document the interactions of specific health disciplinary conventions and knowledges within CIRDI-related research and advocacy efforts involving a major Canadian global health organization. This analysis illustrates both accommodation and resistance to large-scale political economic structures and the need to directly confront the global North governments and sectors pushing extractive-led neoliberal development globally.

Resumen

La investigación sobre los impactos en la salud de la extracción de recursos naturales delata brechas importantes y huellas corporativas y neocoloniales, que plantean dudas acerca de cómo se produce la ciencia. Analizamos la producción de conocimiento sobre los impactos en la salud de la minería en relación con el Instituto Canadiense de Desarrollo y Recursos Internacionales (CIRDI, siglas en inglés), una organización universitaria que cuenta con participación sustancial de la industria extractiva y tiene vínculos con la política exterior de Canadá, la cual es dominada por intereses mineros. Utilizamos un marco de "ecología política del conocimiento" para situar a CIRDI en el contexto del capitalismo neoliberal, los discursos neocoloniales de desarrollo sostenible y las técnicas de responsabilidad social corporativa de la industria minera. Luego, documentamos las interacciones entre los conocimientos y convenciones disciplinarias de salud dentro de los esfuerzos de investigación y promoción relacionados con CIRDI que involucran a una importante organización canadiense de salud global. Este análisis muestra tanto la complacencia como la resistencia a las estructuras políticas económicas a gran escala, y la necesidad de confrontar directamente a los gobiernos y sectores del Norte global que manejan el desarrollo neoliberal impulsado por la extracción a nivel mundial.

Keywords: science and technology studies, global health, commercial determinants, corporations

Introduction

The pursuit of health equity in relation to resource extraction is hampered by distinctive gaps and patterns in available health science, raising questions about how such knowledge is produced.1,2 While occupational studies in global Northa workplaces are plentiful, gaps include a relative neglect of nonoccupational communities affected by extraction; a tendency to dwell on direct toxic exposures and ignore social determinants and mental health pathways; still-preliminary attention to complex social-ecological system dynamics and cumulative impacts of overlapping land uses; and avoidance of the upstream power relations that drive health determinants.2–6 Explanations offered for such patterns include broader neglect of ecological and social context in environmental and occupational health, linked to the field’s historical compromise with industry as a source of worker bodies to study2 (cf. Sellers7). Additional corporate footprints are suggested by the propensity of resource extraction companies to generate science that furthers their commercial interests.8–10 Such influences also intersect with neocolonial aspects of the settler states where much mining-health scholarship is generated2 (cf. Butler11). For example, funding by controversial mining companies of universities and healthcare facilities in Toronto has infamously been accompanied by racist portrayals of the global South countries from which Canadian companies extract enormous wealth.12–14

Tools available to address these patterns include conflict-of-interest analyses, but these typically lack rigorous attention to the larger suite of factors shaping knowledge production.15,16 As a result, studies of corporate influence on health and science have been criticized for conceptualizing industry, and structures such as neoliberalism or colonialism, in simplistic and monolithic ways.16,17 More nuanced analyses of context-dependent corporate influences on knowledge generation have been carried out in support of community resistance to hydraulic fracturing in North America.18 The enormous health implications of resource extraction globally1,5 suggest that such approaches are urgently required at the intersection of health science production and North-South inequities. In this paper, we employ a “political ecology of knowledge” framework19 to understand health knowledge production dynamics in relation to the Canadian International Resources and Development Institute (CIRDI), dynamics which are understood as the interplay of specific research activities with political economic, material, and discursive structures.

CIRDI (or “the institute”) was established with federal government funding in 2013 with a mandate to “Exchang[e] knowledge and expertise with developing countries to enable leading practice natural resource governance, environmental stewardship, gender equality and ultimately, poverty reduction.”20 Activists and critical scholars immediately placed CIRDI in the trajectory of Canada’s decades-long campaign to promote its controversial mining industry globally, extending centuries of violent extraction of wealth from Indigenous territories (cf. Tannock,13 StopTheInstitute,21 Dougherty22). Members of one major Canadian global health organization—the Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research (CCGHR)—responded to such concerns in disparate ways: some seeking to acquire and then subversively apply CIRDI funding to promote health equity in response to resource extraction, and others opposed to engagement with the institute and potential enrollment in its extractive-led development project. Such differences and the conflict they generated, along with the institute’s complex status as a publicly funded body with major corporate involvement and connections to Canada’s foreign policy, provide a rich case study through which to examine the production of health knowledge in relation to resource extraction. We begin by describing the political ecology of knowledge framework and the methods we use to apply it. In analyzing the CIRDI/CCGHR case study, we next unpack the framework’s multiple “layers” of factors shaping knowledge production. While our analysis uncovers colonial legacies and processes of neoliberalization that drive patterns of health inequities and academic inquiry, we also uncover forms of resistance that inspire our concluding recommendations for action.

Political Ecologies of Health Knowledge

Derived from the “ecology of knowledge” metaphor of historian Charles Rosenberg, the political ecology of knowledge framework provides a vehicle for self-reflection among health researchers19 (cf. Rosenberg23). It operationalizes the insight that scientific knowledge generation, rather than being independent of societal contexts, is always profoundly shaped by them.24 The framework extends work in the field of political ecology, in which science about health and the environment is increasingly viewed as “situated” or emerging from—and in turn typically reinforcing—power-laden institutional structures.17,25 Such understandings can enable praxis for environmental justice via specifically political ecologies of knowledge that identify intervention points for transforming inequitable structures.19

The numerous social and material factors that influence knowledge production, which Rosenberg describes as interacting ecosystemically (i.e. in complex cross-scale dynamics), are usefully organized in eight “layers” in a heuristic developed by Akera:26 (1) Historical Eras; (2) Macroscopic Institutions (e.g., neoliberal capitalism); (3) Institutions (established ways of thinking and doing); (4) Occupations and Disciplines; (5) Organizations; (6) Knowledges (especially disciplinary); (7) Material Artifacts (e.g. laboratory apparatus); and (8) Actors (e.g., specific scientists). Akera synthesizes major currents of scholarship on the social production of science to explain how elements of a specific layer affect other elements within and across layers. Such relationships are not viewed as causal in a deterministic sense, but rather as the “successive extension of institutionalized practices, even as social institutions gain further significance through this diffusion.”26 For example, viewing “neoliberal capitalism” as a Macroscopic Institution and tracing its effects on layers such as Institutions and Knowledges requires understanding the local specificities and complications entailed in such impacts (cf. Newson27).

We move through the framework in three groupings (see Table 1): first, Historical Eras, Macro-Institutions, and Institutions, illustrating key themes with materials drawn from CIRDI’s website; second, disciplinary interactions in global health within this structural context; and third, dynamics of specific Organizations, Knowledges, and Actors involved in CIRDI-related health knowledge generation. Exploring the role of Material Artifacts was beyond the scope of our analysis. Choice of methodologies and data sources to populate these groupings was shaped by the social locations and interactions of coauthors belonging to three overlapping organizations: CCGHR; StopTheInstitute, a Vancouver-based anti-CIRDI activist group; and Frente Colibrí, a Canada-Latin America network of early-career health-environment scholars and activists who have seen their training environments (and countries) affected by Canada’s mining industry. As described in more detail below, some CCGHR members began engaging with CIRDI in 2014, obtaining funding for a “Spring Institute” for new global health researchers and eventually publishing peer-reviewed articles reporting on it. Concurrently, StopTheInstitute’s efforts informed within-CCGHR advocacy expressing concern over that organization’s rapprochement with CIRDI. The resulting conflict over CIRDI would spur CCGHR organizational debates and knowledge production over a period of years. Members of Frente Colibrí—including early-career members of both StopTheInstitute and CCGHR—subsequently drew on secondary literature sources to develop an initial draft of the present article, and CCGHR members who had participated in the Spring Institute or related organizational discussions then made empirical and theoretical contributions in commenting on successive drafts. Such CCGHR comments especially helped to populate the Organizations, Knowledges, and Actors layers by drawing on both firsthand experiences and relevant secondary sources. Comparison of sometimes-conflicting interpretations of events between members of the three organizations helped to accomplish triangulation of perspectives and resulted in a more nuanced overall analysis.

Table 1.

Constituent elements of layers in a political ecology of CIRDI-related health knowledge.

| PEK framework layers | Elements |

|---|---|

| Historical eras | • Neoliberal era |

| Macroscopic institutions | • Neoliberal capitalism • Discourse of sustainable development |

| Institutions | • Mining sector corporate social responsibility |

| Occupations and disciplines | • Global health |

| Organizations | • Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research • StopTheInstitute |

| Knowledges | • Mining-health and health impact assessment scholarship • “Activist” knowledges • Conflict-of-interest and corporate influences on health scholarship • Critical and social scientific studies of corporate social responsibility and Canada’s mining industry |

Note. PEK = political ecology of knowledge.

Recognizing that the generation of knowledge inevitably reflects the social circumstances and locations of the people conducting it, it is important to acknowledge the positionality of the article’s coauthors, documented in detail in Supplementary File 1. For example, participation by members of Frente Colibrí and StopTheInstitute in CIRDI- and other extractivism-related advocacy reflects both roles as trainees in the University of British Columbia (UBC) and other mining-affected universities, and experiences of exploitative relationships linking North and Latin America. Such experiences provided a wealth of activist and academic literature from which to assemble much of the analysis. Lived experiences as “outsiders” (i.e. precarious early-career researchers) in the harsh competitive atmosphere of contemporary universities also informed the paper’s focus on university neoliberalization, described in detail below. Similarly, the social location of several members of CCGHR as established researchers allowed for in-depth knowledge of the internal workings of CIRDI, CCGHR, and the Spring Institute, enabled by decades of experience navigating questionable priorities of universities and funders. Finally, the authorship team’s mix of health and social scientists and professionals generated a productive interplay between social theory and imperatives for urgently needed health interventions.

Neoliberalism, Sustainable Development, and Mining Sector Corporate Social Responsibility

During the neoliberal era, elite sectors of countries around the world reacted to economic crises of the 1970s with concerted efforts to appropriate ever-greater shares of societal wealth, “rolling back” the social protections carved out by organized labor and social democratic governments after WWII.28,29 In this section, we outline institutions—neoliberal capitalism, the discourse of sustainable development, and mining sector corporate social responsibility (CSR)—which structured and guided the establishment of CIRDI and subsequent knowledge production activities during this period.

The macroscopic institution of neoliberal capitalism follows “a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade.”28 In keeping with this theory, political leaders in the North such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, as well as international financial institutions, led a 1980/1990s global resurgence of policies such as privatization, deregulation, and reduced government spending on social programs (“austerity”).30 The global spread of such policies has involved context-specific modifications and resistances,16 such as twenty-first-century Latin American “post-neoliberal” governments that have pushed back against neoliberalism via increased social spending, while intensifying “extractivist” activities such as agroindustry and mining.4,29,31 Such extractivist activities have been increasingly financed by and oriented toward China in the twenty-first century, justified by shared rhetorical resistance to Northern-imposed neoliberalization but extending and modestly redirecting its overall modernization trajectories and flows of resources and wealth.32

The neoliberal period has seen especially harsh economic transformations imposed across the South by international lenders.28,29 Promotion of resource extraction is typically central, based on the theory that it will open up economies to foreign investment and spark broader economic growth.10,11 Neoliberal reforms also countered efforts by Southern countries to obtain greater control over their own resources and the income derived from them, which threatened the profits of companies that mine and use resources.29 The 1973 coup that brought Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet to power, for example, was sparked by nationalization of U.S.-owned copper mines and triggered neoliberal reforms (enforced by “state terrorism”), that reduced barriers to foreign extraction of resources and wealth.29 Spurred on by such transformations, mining activity increased dramatically around the world in the post-Cold-War period, with a leading role for Canada’s industry supported by the country’s mining-friendly legal, tax, and investment structures.33 The Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) and TSX Venture Exchange are “the world’s primary listing venues for mining and mineral exploration companies, with more than 1,200 issuers, accounting for almost 50% of global listings in 2018.”34 Canada’s companies and stock exchanges play leading roles in both precious metals mining and high-risk exploration by “junior” companies, facilitating mining by “senior” companies, Canadian, or otherwise.35

Despite the neoliberal period’s global mining boom, however, predicted improvements in standards of living in resource-rich global South countries have typically failed to occur, consistent with the “resource curse” hypothesis.1,29,36,37 For example, Mongolia implemented deep neoliberal reforms and facilitated mining companies’ access to the country’s enormous resources but also saw foreign debt, poverty, and income inequality increase dramatically.38,39 Numerous such stories across the global South suggest that large-scale mining in resource-rich countries overwhelmingly accomplishes wealth creation for Northern corporate interests and their allies, representing an extension of colonial power relations and resource flows, with recent Chinese investments displaying similar tendencies.32,37,40 The neocolonial character of resource-led development is particularly well described by global South scholars and communities: how mineral and metal supply chains tend to concentrate high-value processing and manufacturing, and the overwhelming share of profits, in the global North; how “transfer pricing” and other illicit financial flows allow corporations to evade taxation and transfer wealth North-ward; how large-scale mining takes Southern countries’ energy and water resources and leaves behind environmental contamination; how resistance to mining is frequently criminalized and violently repressed; and how global South sovereignty is curtailed via conditional loans and manipulation by global North interests seeking to ensure unfettered access to resources.4,29,41,42

Such North-South inequities are enabled by metropolitan Southern elites—whether Asian, African, or Latin American—who work with Northern (and increasingly Chinese) interests to facilitate extraction of wealth from rural hinterland areas, justified by and often reinforcing racist narratives.4,32,38,39 In the Latin American nations prioritized by Canada’s mining sector, Afro-descended and Indigenous populations experience pervasive discrimination and poverty.43 White(r) “cultured” elites, in contrast, tend to be overrepresented in positions of wealth and power such as the governments that facilitate foreign extraction of resource wealth, although such dynamics of “mestizaje” take locally specific form across Latin America.43,44 Indeed, Canadian aid to Peru has disproportionately supported projects strengthening the government’s ability to promote mining and overcome community resistance.45 The role of racist narratives in justifying such neocolonial resource flows is exemplified by Barrick Gold founder Peter Munk’s infamous description of gang rape as a “cultural habit” in Papua New Guinea, dismissing concerns over sexual violence perpetrated by security personnel working on Barrick’s behalf (cf. Butler,11 Jeppesen and Nazar14). The “extractivist” Ecuadorian government of President Rafael Correa (2007–2017) similarly promoted large-scale mining while using racist language to dismiss Indigenous and civil society protests against resource extraction as “infantile” obstacles to national progress.46,47 Comparable resonances exist between Canada’s mining-CSR strategies and the racist language employed by Guatemalan elites to dismiss Indigenous resistance to large-scale mines.48

Notwithstanding local particularities, such racist narratives and the persistently North-ward flows of wealth they justify help to explain widespread resistance to mining from countless global South communities and civil society organizations in the neoliberal period (cf. Kirsch10). These obstacles have motivated industry players to undertake major CSR innovations to defuse critique and preserve profitable access to minerals and metals.10,31,49 As Benson and Kirsch50 document, such sectors initially deny negative impacts of their actions, before mounting evidence forces a more sophisticated “strategic management of critical engagement and the establishment of a stopping point, a limit at which reform is presented as sensible and reasonable.” This strategic management has largely been oriented around the concept of “sustainable” mining, institutionalizing distinctive visions of mining’s impacts, and their relationship to economic development.10 CSR initiatives vary across corporations and settings,4,32,51 but numerous organizations with global reach have sought to influence the broader practice and perception of mining and CSR, such as the International Council on Minerals and Metals (ICMM). ICMM, a global mining industry initiative founded in 2001, has consistently sought to distance mining from the “resource curse” phenomenon and mining-associated conflicts, instead indicting poor “host-country” governance and equating mining with poverty alleviation.36 Such efforts establish a “stopping point” to critiques that might actually halt mining projects or the imposition of extractive-led development models.

CSR programs expressing a sustainable mining vision often involve employment opportunities and infrastructure or social spending in mining-affected communities, as well as sponsorship of cultural or academic institutions far from mine sites. Indeed, mining companies donated at least $602.2 Mb to Canada’s thirty-one largest universities in the 1995–2013 period.51 Such CSR efforts were amplified by the Conservative government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper (2006–2015; see Figure 1 for a chronology of Canadian mining CSR). Early in the Harper period, environmental and human rights controversies involving Canadian mining led to a movement for “home-state regulation” that would hold companies to account for their overseas operations.11,49 In response to this threat, mining companies mounted a campaign to portray the sector as a positive contributor to national and global well-being, aided by public funds diverted to support industry CSR activities.36,49 Milestones included the establishment of the Devonshire Initiative, a national industry-civil society CSR organization; the use of Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) funds to support mining company-nongovernmental organization partnerships abroad; and the eventual elimination of CIDA by the Harper government.11,12,36 Following review by a panel that included the CEO of Rio Tinto Alcan and the founding director of the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy (founded with $35 M donated by Barrick’s Peter Munk), CIDA was merged in 2013 with the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, reflecting the conceit that mining-led development would improve living conditions in the global South and a dedicated development agency would therefore be redundant.12

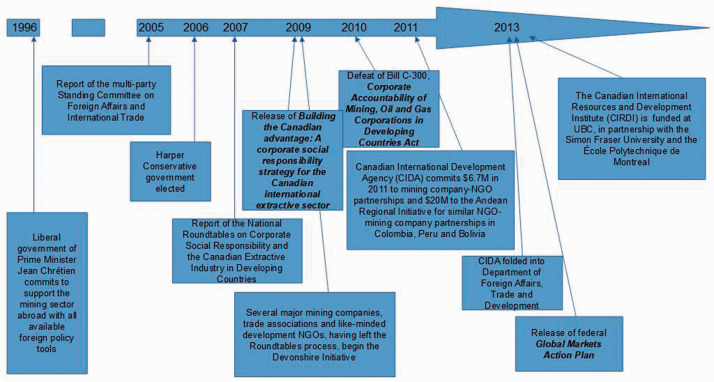

Figure 1.

Timeline of Canadian mining-related corporate social responsibility milestones.

CIRDI = Canadian International Resources and Development Institute; UBC = University of British Columbia; NGO = nongovernmental organization; CIDA = Canadian International Development Agency.

This mining-led foreign policy would crystallize in the November 2013 Global Markets Action Plan, which specified that “all diplomatic assets of the Government of Canada will be marshalled on behalf of the private sector” (quoted in Coumans36). Consistent with this strategy, Prime Minister Harper announced in 2013 that Canada would establish the Canadian International Institute for Extractive Industries and Development (a name that would subsequently be changed) at a Canadian university. Following a successful bid by UBC in partnership with Simon Fraser University (SFU) and the École Polytechnique de Montréal, the Institute was established in 2013 with a $24.6 M federal funding commitment.52 The then Minister for International Cooperation Julian Fantino assured mining industry leaders at this time that the institute would be their “biggest and best ambassador.”53 CIRDI’s strategic partners included mining companies and key players from major mining CSR efforts—the Devonshire Initiative and legal firms specializing in helping the sector avoid responsibility for its overseas activities, for example—attesting to the institute’s role as an extension of such CSR campaigns.54

While not monolithic, CIRDI’s extractive-led development vision tends to further institutionalize central tenets of the mining sector’s CSR vision. The institute’s online documentation consistently blames weak host-country governance for negative effects of extractive projects, such as environmental contamination, a lack of equitable economic development, or conflicts involving mining-affected communities.36 This portrayal mirrors Canada’s interlocking CSR and international development policies, which treat such conflicts as inherently illegitimate and due to poor governance, poor communication of the supposedly universal benefits of mining, or even meddling by environmental nongovernmental organizations in impressionable Indigenous communities.48 Conflicts are never acknowledged as legitimate grievances over differing interests between mining companies and communities. An illustratively comparable framing of mining-related conflict is expressed in a CIRDI-funded report lead-authored by a former head of the major mining trade organization the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada.55 While the report acknowledges colonialism and “neo-liberalism” among the “structural” drivers of mining-associated conflicts, it ignores the role of global North interests in driving and profiting from such processes. “Neo-liberalism”—typically paired in the document with “democratization”—is portrayed as generally beneficial except in countries lacking democratic freedoms and, the report explains, “the necessary strengthening of regulatory frameworks and state capacity.”

Presenting neoliberalism and colonialism in this way coheres with the need to strengthen host-country governance capacity while leaving out the role of the global North in actively weakening such capacities through colonial exploitation and more recent iterations such as neoliberal structural adjustment programs.36 The document can thus advance a theory of conflicts as “natural” features of company-community interactions, amplifying the comments of some interviewed community members who “looked at their relationship with the company as a marriage and the mine was their baby.”55 This portrayal signals a need for gender-focused analyses of mining CSR that are beyond the scope of this paper; in addition, conflicts in such “relationships” feature as amenable to being “transformed” toward “positive” outcomes with appropriate CSR efforts. This portrayal of multi-billion-dollar corporations and mining-affected communities in the global South as loving life partners innovates on mining-CSR’s conflict-as-illegitimate theme (cf. Roy Grégoire48) by portraying conflict as a stop on the road to an ultimately happy marriage (with divorce or an actual halt to mining activities never considered).

The report’s curiously agent-less “colonialism” also suggests additional discursive roots of mining sector CSR. This portrayal ignores the massive wealth transfers colonialism entailed (and still entails) and instead theorizes that different experiences of colonialism in Latin America and Africa have led to cultural characteristics such as “passive-aggressive” behavior in African countries and the “use of conflict” in Latin America.55 This depoliticized portrayal of colonialism is quite consistent with a macroscopic institution we term the discourse of sustainable development. The “discourse of development” enables the practice of international development by portraying “developing countries” as constitutionally or mysteriously poor and in need of Northern help and guidance.56 Such representations give no explanatory weight to colonialism or imperialism, thereby making technical development interventions appear necessary while excluding more radical changes that would threaten the resource differentials created by colonialism. The discourse of development has in the neoliberal era been made “sustainable,” and environmental themes, problems, and sciences now feature in its portrayals of the global South. Nevertheless, such portrayals still overwhelmingly neglect to connect Southern poverty and environmental degradation to ongoing exploitation by largely Northern interests. Sustainable development remains the dominant framework for global development policy, for example, in the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals that posit economic growth with environmental protection as the solution to poverty, permeated by neoliberal faith that markets can solve societal challenges.56,57

As expressed in its website and public materials (though not necessarily across its funded projects), CIRDI’s vision appears largely consistent with such a discourse of sustainable development. A document entitled “CIRDI and the UN Sustainable Development Goals,” for example, makes repeated reference to poverty in countries of the global South where the institute has projects.58 At no point, however, does the document explain the colonial historical roots of such poverty. These are left implicit but appear to mainly consist of a lack of “inclusive and sustainable development of natural resources” and appropriate institutions to guide it. CIRDI’s documentation thus conveys a telling framing of mining and development, cohering with both the discourse of sustainable development and related mining-CSR narratives (but in nonmonolithic ways that reflect heterogeneity among CIRDI’s partners and fundees). It is only by omitting Northern extractive interventions that have driven global South poverty and associated mining-associated conflicts that CIRDI’s materials can present a well-governed continuation—and indeed intensification—of such extraction as an appropriate solution. CIRDI thus tends to reinforce the sense that resource-led development is in everyone’s best interests, and opposition to it is inherently irrational, or fated to disappear with appropriate governance.

Disciplinary Dynamics: Neoliberalized Knowledge Production in Global Health

The neoliberal-era institutions conditioning the emergence and vision of CIRDI also shape activities within specific academic disciplines or fields, in ways that ultimately play out in health knowledge production processes. University neoliberalization—a component of broader neoliberal transformations—has involved widespread reductions in state investments in higher education and increased pressure on universities to align research and teaching with corporate interests.59 Such reforms generally increase private sector involvement in funding and steering higher education, which has concurrently adopted opaque and centralized governance structures that are more responsive to industry needs.13 In the Canadian context, deep cuts to university education in the 1980s and 1990s were succeeded by a major influx of new public funding in 1997, specifically aimed at making universities more “business-like.”27 National-level policy measures announced by the Liberal government at this time, with a budget of $3.15B to 2010, included promotion of “partnered” research, commercialization, and “innovation” through national research funding councils, Centers of Excellence, and on-campus centers promoting university-corporate partnerships; legislation to allow private ownership of intellectual property created with government grants; and mechanisms encouraging universities to compete with each other for funds, such as the Millennium Research Chairs (now Canada Research Chairs) program. Requirements to obtain matching funds (typically from industry) were later applied to greater numbers of Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant competitions by the Conservative government in 2014.60

University neoliberalization thus provided numerous “receptor sites” for mining sector CSR efforts in the form of universities hungry for funds, and researchers pushed to partner with industry. Indeed, UBC provided a natural neoliberal home for CIRDI, as illustrated by the university’s explicit promotion of private-sector interests, aggressive pursuit of private funds, and rebranding of university infrastructure to reward donations.61 While allied with numerous commercial sectors, UBC received at least $86.5 M from mining companies from 1995 to 2013 (not counting large but undisclosed donations from the controversial Goldcorp), the most of any Canadian university and 10.8% of all its private donations.51 In the same period, UBC’s partners in founding CIRDI received at least $22 M (SFU) and $19.9 M (Université de Montréal, with which École Polytechnique de Montréal is affiliated).51

Career advancement in such neoliberalized universities increasingly depends on “accountability” metrics such as high impact-factor publications, patents, and grant dollars, with insidious influences on knowledge production patterns.62 Such tendencies take discipline-specific shape in the field of global health, which emerged during the neoliberal era’s transformation of knowledge production. The field’s dominant metrics and approaches have been criticized, using theories of neoliberalism, for emphasizing private-sector partnerships and pursuit of “health as an investment” via market-friendly, though questionably effective, technical, and downstream solutions to health problems.15,63 Global health’s neoliberal tendencies also draw on disciplinary conventions refined over time in the public health sciences. For example, the “epidemiology wars” of the turn of the twenty-first century debated whether the field should emphasize “advocacy” on behalf of marginalized groups or should instead be an “objective” science.64 One illustrative installment in these “wars” centered on the health effects of Texaco’s (now Chevron’s) decades of petroleum extraction in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In this debate, numerous public health researchers took issue with epidemiologist Kenneth Rothman’s support for Texaco’s defense against a lawsuit launched by Amazonian peasant and Indigenous groups.65 A response by Rothman and Arellano, however, interpreted their role as merely carrying out rigorous scientific activities under contract to a giant transnational company while “elevating the level of scientific discourse” (quoted in Brisbois65).

This response reflects a common tendency for scientific activities on behalf of corporations to be deemed “objective” while overt advocacy on behalf of marginalized groups experiencing corporate-induced harms is deemed “biased” (cf. Wylie18). Such attitudes overlap with objectivity norms in environmental and occupational health sciences, with their roots in an early-twentieth-century compromise with industry that allowed development of the field of industrial hygiene.7 Historically, the (fictitious) ideal of science as possible and desirable to do independent of social influence—the “god trick”—evolved in ways that obscured and naturalized the patriarchal, racist, and classed structures enabling the practice of science.24 Thus, longstanding and problematic objectivity ideals of health scientists provide discursive resources to defend corporate involvement with—and thus neoliberalization of—knowledge production.

Neoliberalization of knowledge production and reactions to it also interact in distinctive ways with colonial legacies. Global health’s pursuit of North-South “partnerships” attempts to transcend the inequitable research relationships said to characterize the “international health” era.66 Northern global health researchers and small numbers of Southern “partners” nevertheless continue to benefit from the persistence of North-South disparities, and often-neocolonial representations of them, in generating rapid publications and other outputs that advance careers in neoliberal universities.62,63,66 Such rapid outputs are facilitated by the pursuit of technical downstream “solutions” to global health problems, often responding to discourse-of-sustainable-development representations portraying the global South as impoverished by geographic bad luck, or by lack of integration into global markets.67 For example, pesticide epidemiology articles about Latin America often portray it as accidentally or constitutionally poor, helping to identify publishable contributions to knowledge about “developing countries” in ways that are shaped by disciplinary and genre conventions of public health journals17 (cf. Hall and Sanders62). Reactions to such neocolonial representations, in contrast, include “market failure” global health work that foregrounds the influence of colonial legacies and neoliberal globalization on patterns of health and illness, and aims at health equity via reduction of North-South power and resource differentials.67 Knowledge production in global health thus reflects disciplinary dynamics of public health and epidemiology, shaped by and sometimes pushing back against neoliberal capitalism’s colonial continuities and influences on knowledge production.

Organizations, Knowledges, and Actors: The CCGHR’s Mongolia Spring Institute

The institutional and disciplinary dynamics described above represent structural context for health knowledge generation occurring in relation to a 2015 global health capacity-building initiative held in Mongolia, partially supported by CIRDI and organized by a team including members of CCGHR (a member-based not-for-profit organization with “five hundred+ members in forty-nine countries” and twenty-nine leading Canadian universities as institutional members; www.ccghr.ca). Mongolia’s “staggering reserves” and faithful adherence to neoliberal reforms imposed by international lenders had both compromised traditional pastoralist livelihoods and made the country a mining hotbed, most notably involving the Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mine.38,39 A 2007 workshop of Canadian and Mongolian CCGHR members identified a need for tools that could balance the growing influence of Canadian mining companies such as Ivanhoe Mines, which owned Oyu Tolgoi before it was purchased by Rio Tinto. The resulting Canada-Mongolia research and knowledge translation partnership—one of many such partnerships led by CCGHR members in countries around the world—included university academics, civil society actors, public sector decision-makers, and World Health Organization representatives in an effort to improve consideration of health in environmental assessment processes.68 It built on earlier ethnographic research on health in a “post-socialist” context experiencing rapid market reforms and was consistent with “market failure” streams of global health described above in its critique of neoliberalism’s health impacts (cf. Janes and Chuluundorj39). The 2015 Spring Institute was planned as an extension of this collaboration that would address policy and governance gaps with respect to Health Impact Assessment (HIA), a governance tool increasingly applied prior to new mining developments.3 It responded to interest from Mongolian collaborators and addressed concerns over the neoliberal retreat of state control over the resource sector, in a context where the ongoing Canada-Mongolia partnership had managed some knowledge translation “wins” such as a legislated requirement to conduct HIA prior to new mines in Mongolia.68

HIA draws on a balance of environmental health and social determinants of health scholarship.69,70 Calls to focus HIAs more narrowly on environment-health links and avoid putting “private companies in the de-facto role of ministry of health”69 have been tellingly voiced by the designers of HIA guidance for the International Finance Corporation (the World Bank’s private-sector lending arm), which mandates HIA for projects it finances.70 Many HIAs are indeed carried out by industry consultants, and the resulting assessments have been criticized for systematically underestimating risks to health.9 Mining-related HIAs also draw on existing scholarship on mining and health, including occupational epidemiology studies that dominate that literature but also more diverse evidence types covering ecosystem change and social determinants of health such as income inequality and social services.3 Notwithstanding such holism, however, the use of HIA to address mining-induced harms in countries of the global South appears broadly consistent with mining-CSR’s tendency to introduce a “stopping point” to critique and manage debate over mining’s impacts.50 HIA is typically focused at project or “local” scales, leaving global environmental change, neoliberal macroeconomic transformations, and other large-scale colonial legacies largely “off the table” as targets for change.9,71,72 Consistent with the fact that the International Council on Minerals and Metals and International Finance Corporation both endorse the tool, it is not clear if a large-scale mining project has ever been halted as a result of an HIA showing unacceptable health implications. Such limitations of HIA—which reflect pronounced corporate fingerprints—were addressed in the Canada-Mongolia collaboration through a focus on social determinants of health and equity, engagement with cumulative impacts of mines and overlapping land uses at regional scales, and efforts to empower mining-affected communities via participatory workshops linking them with policymakers.68

The extension of such Knowledges via the Canada-Mongolia collaboration and Spring Institute also informed and was shaped by ongoing (Organization-layer) CCGHR discussions and initiatives, such as development of guidelines for North-South partnerships and a published set of principles for equity-informed global health research.73 Additional influences included previous CCGHR “Summer Institutes” for new global health researchers, and formal evaluations of them.74 Summer Institutes in locations around the world had played major roles in CCGHR’s overall programming, and especially development of relationships between Canadian and Southern researchers and trainees. In 2014 and 2015, however, CCGHR’s overall finances were tenuous and public funding sources were increasingly directed toward “partnered” research.75 In this funding climate, which expressed neoliberal capitalism’s impacts on research institutions, CIRDI represented a source of public funds at a scale larger than could be obtained from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research,, which would only contribute to the 2015 Spring Institute in the form of a small meetings grant. CIRDI was approached with a request for the amount required to complete the envisioned program and responded with funds to support travel for some participants, as well as some CCGHR staff involvement in the Spring Institute. While helping to support a CCGHR-linked activity, these funds were administered by the principal investigator’s home university.

While preparations for the Spring Institute were underway, however, criticisms of CIRDI’s development model and questionable “strategic partners” began to surface, notably voiced by the StopTheInstitute, a “concerned group of UBC and SFU students, in collaboration with mining justice activists and members of various Vancouver diaspora communities.”21 Members had initially sought to learn about and shape the nascent CIRDI, but found their inquiries consistently rebuffed by UBC, which went so far as to engage a consultant to manage student protests. Such responses exemplify neoliberal universities’ opaque and centralized governance structures and the Conservative government’s notoriously tight control of information that might hinder its promotion of private (especially extractive) sector interests, reflecting the institute’s identity as a manager of federal development assistance funding. This approach is demonstrated by CIRDI’s hiring as CEO of Cassie Doyle, previously the Deputy Minister of Natural Resources Canada during the Harper administration. Doyle’s approach to managing debate on resource extraction is illustrated by emails obtained by Greenpeace, in which a Canadian government official summarizes Doyle’s comments to a Canada-U.S. roundtable of government and extractive industry representatives: “we need to meet an active, organized anti-oil sands campaign with equal sophistication.”76

In response to such strategies, StopTheInstitute carried out an escalating series of tactics including numerous freedom-of-information requests to overcome CIRDI’s secrecy, essentially generating activist knowledge via informal public policy research methods and making it available on their website.21 Frustration with CIRDI’s secrecy also motivated forceful and sometimes derisive communications strategies, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

StopTheInstitute visuals.

CCGHR discussions during the Mongolia Spring Institute’s planning phase recognized StopTheInstitute’s concerns but took issue with their aggressive tone and asserted the hope that “the goals of the institute [might] be reshaped (or to some, subverted) to further Canadian accountability.”77 Additional CCGHR member perspectives voiced at this time criticized CIRDI’s lack of responsiveness and adequate communication with potential academic partners (CCGHR members who attended preliminary consultations would also later describe numerous competing visions seeking to shape CIRDI’s activities, and a degree of disorganization that impaired the institute’s effectiveness). This conversation would be expanded in early 2015 when five CCGHR members—informed by StopTheInstitute’s efforts—sent a letter of concern to the organization’s Board of Directors. The signatories affirmed their confidence that the Spring Institute organizers would develop an “outstanding curriculum” independent of CIRDI’s influence but worried that CCGHR might be enrolled in patching up the tattered image of CIRDI’s mining-sector stakeholders, also compromising the ability of CCGHR members to partner as allies with mining-affected communities. The letter of concern would trigger a process of CCGHR organizational reflection and knowledge production, as described below.

In the short term, however, the 2015 Spring Institute would go ahead as planned, with one CIRDI representative in attendance. CCGHR tweeted regular updates during the “@CIIEID_ICIIED @CCGHR Health Impact Assessment program,” reflecting CIRDI’s original name and Twitter handle. Despite the harmonious image suggested by such tweets, however, CCGHR members involved in organizing and running the Spring Institute would later report a variety of issues encountered in working with CIRDI, from seeing their Mongolian partners treated as employees, to CIRDI’s efforts to “claim” the initiative, as in a website statement that “CIRDI, in partnership with the CCGHR, delivered a pilot course in Mongolia in April/May 2015.”78 And while CIRDI’s support was generally consistent with the Mongolia HIA program’s identity as capacity-building for governance in a mining “host country,” the eventual knowledge emerging from the Spring Institute displays marked dissonances with CIRDI’s (heterogeneous) extractive-led development model. In contrast with CIRDI’s attribution of blame for mining’s negative impacts to poor host-country governance, for example, a paper reporting on evaluation of the Spring Institute highlights “power imbalances … between nation states” that may inhibit attempts to protect health, as in “investment agreements that benefit Canadian mining companies, in exchange for development aid.”3 The paper also discusses home-country (e.g. within-Canada) regulation of transnational mining companies and—citing radical Indigenous scholars—“certain structures” that maintain power imbalances involving mining-affected communities. Thus, while the article invokes “sustainable development goals,” it nevertheless pushes back against the depoliticizing discourse of sustainable development by working critiques of North-South power imbalances into an evaluation article.

Similar contingencies emerged in organizational deliberations sparked by the letter of concern to the Board of Directors, in parallel with the multi-year process leading to the Spring Institute evaluation article. These conversations initially tended to emphasize the “public” nature of CIRDI’s funding, with StopTheInstitute’s previous investigative work required to clarify the fact that CIRDI’s start-up funds were intended to be supplemented by financial and in-kind contributions, as illustrated in the institute’s contribution agreements from mining and other private-sector partners.54 Another recurring theme, despite the letter signatories’ faith that CIRDI’s funding “would have no bearing on SI-8’s content,” was whether or not CIRDI would have, or did have, any influence on the Spring Institute content. Such concerns appear to reflect the general preoccupation with “objectivity” (and its inverse, “bias”) in epidemiology and global health, as opposed to more complex understandings of corporate influence (cf. Herrick16). Over time, CCGHR members gradually developed more nuanced perspectives by engaging with Knowledges such as public health scholarship on conflict-of-interest, related analyses of corporate influences on health and science, and critical and social scientific studies of CSR and Canada’s mining industry (cf. Brisbois15). Results included two conference workshops and a journal commentary on corporate funding of global health research,15 involving cooperation between signatories to the letter of concern and organizers of the Mongolia Spring Institute.

This collaboration also illustrates the important role of disciplinary conventions and identities in shaping Organizational responses to corporate and broader neoliberal influences on knowledge production. Leadership roles in the period following the letter of concern over the CCGHR-CIRDI partnership were typically offered to trainees, such as the postdoctoral fellow who led the corporate funding commentary (and the present analysis). When an early draft of the commentary was then circulated to coauthors, highlighting Barrick Gold founder and U of T benefactor Peter Munk’s admiration for Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, coauthors took issue with language describing Pinochet’s “mass torture and ‘disappearances’ of dissidents,” dismissively alluded to by Munk in a 1996 speech to Barrick shareholders (cf. Ismi79). One proposed edit—offered in the spirit of developing a publishable commentary aimed at public health peers—suggested “more cautious or objective language” that would express facts “in an academic or objective way.” This interaction attests to previously discussed objectivity/advocacy tensions in public health. The interaction of such tensions with attitudes toward industry involvement also emerged in another CCGHR member’s intervention into discussions over CIRDI, urging a “balanced debate with input from private sector players.”

Reflecting such coauthorship discussions and the challenges of fitting an argument into a 1500-word commentary, the final article avoids reference to any specific company, instead citing overall dollar figures for mining sponsorship of Canadian universities. It also refers to “the effects of large-scale mining on local environments,” as well as “violence by mine security personnel against local communities.”15 This language is indeed less charged than the association of a major university benefactor with “mass torture,” with reference to broader trends skirting the evocative controversies surrounding specific companies. The draft article also evolved from presenting a general framework for understanding the impacts of corporate funding on health research to instead offer three questions “to promote a cautionary and intentional approach to considering relationships with corporate funders.” Challenges to mining-led neoliberal development do appear in one of these questions, asking whether accepting corporate funding might “legitimiz[e] corporations or models of development that are at the root of many global health problems.” Nevertheless, framing the article as a relatively palatable “helpful heuristic to guide reflection”—and not as a direct intervention against mining or corporate involvement in knowledge production more generally—appears to have directed the debate away from the charged issues raised by StopTheInstitute and other critics of Canadian mining overseas. This commentary and the Mongolia Institute evaluation article thus illustrate how CCGHR Organizational dynamics involving specific Actors and the extension of academic Knowledges were conditioned by and pushed back against broader institutional contexts in context-specific or contingent ways.

Discussion

Our analysis has situated health knowledge production activities against the backdrop of neoliberal capitalism, the discourse of sustainable development, and mining-sector CSR efforts, via pathways involving specific scholarly disciplines or fields. The use and extension of existing knowledges within particular organizations illustrates both “top-down” structural influences, and the context-dependent ambiguities and tensions involved in pursuing health equity amidst particular institutional pressures and priorities (cf. Newson27). Our analysis of our own activities drew on our lived experiences and related immersion in relevant literatures but also represents a partial perspective, notwithstanding involvement of coauthors from different disciplinary, national and career-stage backgrounds in (con)testing its arguments. Particularly conspicuous is the absence of Mongolian researcher and mining-affected community voices, reflecting the process through which this analysis evolved (i.e. as an activist effort by early-career scholars who were subsequently joined by a broader and more-established authorship team) and a lack of resources for ethically responsible involvement of Southern researchers in reflecting on a global health partnership.

Acknowledging such limitations, our findings provide a North-South complement to emerging work on the production of health science in North American community encounters with extractive industry.18 They also extend political ecology of health’s application of situated knowledge approaches by involving practicing health professionals and researchers in praxis-oriented self-reflection, identifying intervention points by mapping “entanglements” in neoliberal universities and other inequity-producing structures19 (cf. Jackson and Neely25). Our analysis underscores the importance of going beyond conflict-of-interest thinking to document the pervasive but contingent and contested impacts of corporations and their allies on the production of health science, within broader neoliberal and neocolonial structures.15,16 In extending the Harper government’s mining-CSR strategy, CIRDI’s influence was as likely to elicit annoyance as to inspire greater belief in mining-led development (although rigorous assessment of the effect of partnering with CCGHR on the legitimacy of CIRDI or extractive-led development was beyond the scope of the analysis-cf. Brisbois,15 Antonelli,49 Hamilton51). Indeed, the 2015 Spring Institute generated knowledge, within a critical or “market failure” global health research program, that pushed the corporate-influenced boundaries of mining-health and HIA scholarship and challenged CIRDI’s guiding vision of development. A commentary originating in an overt challenge to CIRDI, in contrast, evolved through coauthorship deliberations to a point where its recommendations became compatible with accepting corporate funding. These deliberations involved organizational imperatives to mentor trainees and communicate a novel combination of scholarly knowledges, conditioned by specific publication genres and public health’s interplay between “objectivity” and “advocacy.” Such interactions show the importance of context-dependent organizational, personal, and disciplinary dynamics in mediating corporate (and neoliberal/neocolonial) pressures on health knowledge production.

Such nuance, however, does not eliminate the need for concern. Objectivity ideals and desires for “balance” through inclusion of corporate voices voiced in CCGHR debates evoke comparable norms in environmental health sciences, where they often function to dismiss the concerns of racialized and other marginalized groups involved in environmental justice struggles.18 Such tendencies have been highlighted in relation to hydraulic fracturing, a practice made possible by the neoliberal reduction of environmental protections and industry-involved (but publicly funded) research into fracking technologies—accompanied by pervasive charges of “bias” leveled at environmental health researchers choosing to partner with marginalized communities.18 As with Kenneth Rothman’s “scientific” support to Chevron’s evasion of responsibility for its enormously profitable contamination of the Ecuadorian Amazon (cf. Brisbois65) moreover, such ideals in CCGHR deliberations over CIRDI and corporate funding appeared to de-emphasize uncomfortable realities about Northern (and corporate) involvement in the global South. By functioning to tone down challenges to the benevolent image of Canadian mining and related development models abroad,11,49 public health’s objectivity norms thus complicate efforts to confront the ongoing exploitation of marginalized global South communities.

Identification of the global North social location from which much conventional health science is produced is one way to promote stronger forms of methodological rigor that are not premised on an imaginary position outside of processes such as patriarchy, racism, and colonialism.24,80 Our analysis also holds additional praxis implications for health researchers concerned with remedying legacies of colonialism. Numerous global health research programs already confront such legacies (and continuities) while creatively or subversively navigating neoliberal university incentive structures. Such critical global health traditions are foundations of the present analysis, and many of us have worked and learned within them. Our focus on one such initiative, targeted at mining in a global South country and funded by one of the world’s leading mining powers, helps to clarify how they might be extended to realize the potential inherent in their perceptive approaches to health equity, North-South partnerships, and participatory research. Efforts to “stretch” HIA by discussing cumulative impacts at regional scales, for example, invite consideration of a larger stretch to more directly confront the international financial institutions, global North governments, and mining transnationals steering global South countries’ development models toward mining and other “extractivist” activities (cf. Campbell and Hatcher,38 Janes and Chuluundorj39). Consistent with CCGHR’s emphasis on global health research informed by the principle of “responsiveness to causes of inequities,”73 the fact that such global North interests prominently include the Canadian governments and mining companies funding universities and research projects identifies an important but neglected intervention point.

Beyond the inequitable health and environmental impacts typically associated with individual mines,1,3–5,12 the neoliberal austerity measures included in extraction-led development models generate widespread obstacles to health equity, such as reduced health system capacity, environmental deregulation, and social determinants challenges such as precarious work and income inequality.6,30,39,63 Importantly, promotion of mining-led neoliberal reforms in the global South has continued under the Harper regime’s successor, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.45 Further urgency stems from the ways in which “claims” on mineral resources by Canada’s mining sector and government allies are enabled by and reinforce racialized hierarchies and racist narratives, both at home and abroad.11,46,48 Such realities should clearly trouble—and change the professional lives of—global health researchers and others who aim toward more equitable partnerships with Southern colleagues and communities.

Direct political action at the level of Canadian (and other global North countries’) foreign policies is one still-underutilized way to leverage the higher education and health sectors’ privileged societal roles and challenge neocolonial inequities. Such engagement must push back against university neoliberalization while extending (some) global health researchers’ prioritization of community perspectives and Southern scholarship, such as Latin American analyses of mining’s impacts.4,29,31 It must at the very least bring about meaningful home-state regulation of transnational mining companies, leading to a broader transformation of extractive-led development and the neoliberal principles built into global efforts such as the Sustainable Development Goals—principles which extend the legacies of colonialism and further global environmental degradation.57 Growing recognition of neoliberalism’s failures, the global resurgence of right-wing racist governments, and crises such as climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted the failures of dominant development models. Health researchers and professionals must take advantage of this opening to ensure that their efforts to promote health equity are not figuratively or literally undermined.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-new-10.1177_10482911211001051 for Mining, Colonial Legacies, and Neoliberalism: A political Ecology of Health Knowledge by Ben Brisbois, Mathieu Feagan, Bjorn Stime, Isaac K. Paz, Marta Berbés-Blázquez, Juan G. Chávez, Donald C. Cole, Erica Di Ruggiero, Lori Hanson, Craig R.Janes Katrina M. Plamondon, Jerry M. Spiegel and Annalee Yassi in NEW SOLUTIONS: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy

Acknowledgments

Insightful comments on earlier drafts of the present paper by Colleen Davison, Charles Larson, Lesley Johnston, Jennifer Moore, Patricia Polo, and two anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged, as is Dr. Craig Slatin’s editorial guidance.

Author Biographies

Ben Brisbois is a researcher, educator, and advocate on social and environmental justice themes. Areas of focus include pesticides and health in Ecuador’s banana industry, resource extraction, global environmental change, and the social production of health science.

Mathieu Feagan is a critical interdisciplinary scholar whose work focuses on knowledge mobilization for climate justice across diverse communities of professionals, activists, and researchers.

Bjorn Stime’s work explores Canadian health professionals’ alignment with settler state interests in maintaining access to Indigenous peoples’ land. His work in this area aims to facilitate dialogue toward dismantling colonial practices.

Isaac K. Paz is a researcher with more than ten years of experience studying health, environmental, and societal impacts of the mining industry in southern Bolivia.

Marta Berbés-Blázquez is an interdisciplinary scholar whose research considers the human dimensions of social-ecological transformations with an emphasis on vulnerable communities.

Juan Gaibor is a professor and coordinator of the Environmental Center at the State University of Bolívar (Ecuador). His research and teaching focuses on health-environment interactions and how they are socially determined by structural forces.

Donald C. Cole is a public, occupational, and environmental health physician, with more than forty years of practice (clinical and population-related), research, and policy work in Canada and lower and middle-income countries. As an emeritus professor of the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, consultant, and farmer, he engages in social-ecological practice.

Erica Di Ruggiero is an associate professor, Social and Behavioural Health Sciences Division and Director, Centre for Global Health at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto. Her research focuses on health equity impacts of policy and program interventions within and outside the health sector (e.g. employment conditions), and on how global policy agendas (e.g., the Sustainable Development Goals) are shaped by different types of evidence.

Lori Hanson is an associate professor in the Department of Community Health and Epidemiology at the University of Saskatchewan. Identifying as an activist-scholar of global health, her research both studies and engages with social movements for health, including those that resist extractivism in their communities.

Craig R. Janes is a medical anthropologist interested in and committed to social science approaches to public health and global health policy. He has research strengths in human-environment interactions, social inequities and health, global health governance, and maternal and child health.

Katrina M. Plamondon is a Canadian woman of Cree and settler ancestry. An assistant professor in the School of Nursing at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, her program of research focuses on questions of how to align knowledge, intention, and action for health equity.

Jerry M. Spiegel is a global health researcher with a focus on global systems that drive inequities as well as processes of resistance that promote health equity. He has more than forty years of experience in Canada, Latin America, and southern Africa.

Annalee Yassi is an occupational and environmental health physician with more than forty years of practice (clinical and population-related), research, and policy work in Canada, Latin America, and southern Africa. Her particular focus is on respectful partnerships in conducting action research with a focus on equity.

Notes

We use the terms (global) South and North to capture the reality of vast wealth disparities reflecting the broad contours of colonialism. The role of emerging powers such as China and Russia, the existence of “fourth world” conditions within global North nations, the presence of affluent minorities in global South countries, and the sordid history of such generalizations all attest to the need to complicate them whenever possible.

All financial figures in the paper are in Canadian dollars.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Ben Brisbois reports personal fees from the Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research, outside the submitted work.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Ben Brisbois https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1947-5490

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.London L, Kisting S. The extractive industries: can we find new solutions to seemingly intractable problems? NEW Solut J Solut 2016; 25: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisbois BW, Reschny J, Fyfe TM, et al. Mapping research on resource extraction and health: a scoping review. Extr Ind Soc 2019; 6: 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston L, Davison C, Lkhagvasuren O, et al. Assessing the effects of a Canadian-Mongolian capacity building program for health and environmental impact assessment in the mining sector. Environ Impact Assess Rev 2019; 76: 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solíz Torres MF, Yépez Fuentes A, Sacher Freslon W. Fruta del norte: La manzana de la discordia - Monitoreo comunitario participativo y memoria colectiva en la comunidad de El zarza. Quito: Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar and Ediciones La Tierra, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schrecker T, Birn A-E, Aguilera M. How extractive industries affect health: political economy underpinnings and pathways. Health Place 2018; 52: 135–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roelofs C. The extractive industries: asserting their place in global health pedagogy. NEW Solut J Solut 2016; 25: 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sellers CC. Hazards of the job: from industrial disease to environmental health science. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egilman D. Exposing the “myth” of ABC, “anything but chrysotile”: a critique of the Canadian asbestos mining industry and McGill University chrysotile studies. Am J Ind Med 2003; 44: 540–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watterson A, Dinan W. Health impact assessments, regulation, and the unconventional gas industry in the UK: exploiting resources, ideology, and expertise? NEW Solut J Solut 2016; 25: 480–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirsch S. Mining capitalism: the relationship between corporations and their critics. Oakland: University of California Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler P. Colonial extractions: race and Canadian mining in contemporary Africa. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birn A-E, Shipton L, Schrecker T. Canadian mining and ill health in Latin America: a call to action. Can J Public Health 2018; 109: 786–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tannock S. Learning to plunder: global education, global inequality and the global city. Policy Futur Educ 2010; 8: 82–98. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeppesen S, Nazar H. Beyond academic freedom: Canadian neoliberal universities in the global context. TOPIA Can J Cult Stud 2012; 28: 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brisbois B, Cole DC, Davison CM, et al. Corporate sponsorship of global health research: questions to promote critical thinking about potential funding relationships. Can J Public Health 2016; 107: E390–E392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrick C. On the perils of universal and product-led thinking: comment on ‘how neoliberalism is shaping the supply of unhealthy commodities and what this means for NCD prevention’. Int J Health Policy Manag 2020; 9: 209–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brisbois BW, Spiegel JM, Harris L. Health, environment and colonial legacies: situating the science of pesticides, bananas and bodies in Ecuador. Soc Sci Med 2019; 239: 112529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wylie S, Liboiron M, Shapiro N. Making and doing politics through grassroots scientific research on the energy and petrochemical industries. Engag Sci Technol Soc 2017; 3: 393. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brisbois BW, Burgos Delgado A, Barraza D, et al. Ecosystem approaches to health and knowledge-to-action: towards a political ecology of applied health-environment knowledge. J Polit Ecol 2017; 24: 692–715. [Google Scholar]

- 20.CIRDI. Who we are. Vancouver, BC: Canadian International Resources and Development Institute, https://cirdi.ca/about/who-we-are/ (accessed 6 January 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21.StopTheInstitute. Stop the Institute/CIRDI | Holding UBC & SFU accountable to their human rights commitments. Stop the Institute/CIRDI, http://stoptheinstitute.ca (accessed 6 January 2021).

- 22.Dougherty ML. Scarcity and control: the new extraction and Canada’s mineral resource protection network. In: Deonandan K, Dougherty ML. (eds) Mining in Latin America: critical approaches to the new extraction. London: Routledge, 2016, pp.83–99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg C. Toward an ecology of knowledge: on discipline, context, and history. In: Oleson A, Voss J. (eds) The organization of knowledge in modern America, 1860–1920. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, pp.440–455. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haraway D. Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem Stud 1988; 14: 575–599. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson P, Neely AH. Triangulating health: toward a practice of a political ecology of health. Prog Hum Geogr 2015; 39: 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akera A. Constructing a representation for an ecology of knowledge: methodological advances in the integration of knowledge and its various contexts. Soc Stud Sci 2007; 37: 413–441. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newson J. The university on the ground: reflections on the Canadian experience. In: Luxton M, Mossman MJ. (eds) Reconsidering knowledge: feminism and the academy. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishers, 2012, pp.96–127. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harvey D. A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machado Aráoz H. El auge de la minería transnacional en América Latina. De la ecología política del neoliberalismo a la anatomía política del colonialismo. In: Alimonda H. (ed) La naturaleza colonizada: Ecología política y minería en América Latina. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2011, pp.135–180. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrecker T. Neoliberal epidemics’ and public health: sometimes the world is less complicated than it appears. Crit Public Health 2016; 26: 477–480. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svampa M. Modelos de desarrollo, cuestión ambiental y giro eco-territorial. In: Alimonda H. (ed) La naturaleza colonizada: Ecología política y minería en América Latina. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2011, pp.181–215. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez-Vicente R. South–south relations under world market capitalism: the state and the elusive promise of national development in the China–Ecuador resource-development nexus. Rev Int Polit Econ 2017; 24: 881–903. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deneault A, Sacher W. Imperial Canada Inc: legal haven of choice for the world’s mining industries. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Natural Resources Canada. Minerals and the economy. Ottawa, Canada: Natural Resources Canada, https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/our-natural-resources/minerals-mining/minerals-metals-facts/minerals-and-economy/20529 (2018, accessed 6 January 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heidrich P. Determinants, boundaries, and patterns of Canadian mining investments in Latin America (1995–2015). Lat Am Policy 2016; 7: 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coumans C. Minding the “governance gaps”: re-thinking conceptualizations of host state “weak governance” and re-focussing on home state governance to prevent and remedy harm by multinational mining companies and their subsidiaries. Extr Ind Soc 2019; 6: 675–687. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gamu J, Le Billon P, Spiegel S. Extractive industries and poverty: a review of recent findings and linkage mechanisms. Extr Ind Soc 2015; 2: 162–176. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell B, Hatcher P. Neoliberal reform, contestation and relations of power in mining: observations from Guinea and Mongolia. Extr Ind Soc 2019; 6: 642–653. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janes CR, Chuluundorj O. Making disasters: climate change, neoliberal governance, and livelihood insecurity on the Mongolian steppe. Santa Fe: SAR Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordon T, Webber JR. Blood of extraction: Canadian imperialism in Latin America. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misoczky MC, Böhm S. Resisting neocolonial development: Andalgalá’s people struggle against mega-mining projects. Cad EBAPEBR 2013; 11: 311–339. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kistnasamy B, Yassi A, Yu J, et al. Tackling injustices of occupational lung disease acquired in South African mines: recent developments and ongoing challenges. Glob Health 2018; 14; 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roitman K, Oviedo A. Mestizo racism in Ecuador. Ethn Racial Stud 2017; 40: 2768–2786. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Escobar A. Displacement, development, and modernity in the Colombian Pacific. Int Social Science J 2003; 55: 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown S. Foreign aid, the mining sector and democratic ownership: the case of Canadian assistance to Peru. Dev Policy Rev 2020; 38: O13–O31. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martínez Novo C. Ventriloquism, racism and the politics of decoloniality in Ecuador. Cult Stud 2018; 32: 389–413. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore J, Velásquez T. Water for gold: confronting state and corporate mining discourses in Azuay, Ecuador. In: Bebbington A, Bury J. (eds) Subterranean struggles: new geographies of extractive industries in Latin America. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012, pp.119–148. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy Grégoire E. Dialogue as racism? The promotion of Canadian dialogue” in Guatemala’s extractive sector. Extr Ind Soc 2019; 6: 688–701. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antonelli M. Canadá entre la sed insaciable de cordillera y la performance de democracia. In: Memoria seminario internacional. Santiago, Chile: Observatorio Latinoamericano de Conflictos Ambientales and Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina, 2014, pp.94–110.

- 50.Benson P, Kirsch S. Capitalism and the politics of resignation. Curr Anthropol 2010; 51: 459–486. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamilton K. Savoir, pouvoir et standpoint institutionnel: L’impact de la philanthropie minière sur la production du savoir dans les universités canadiennes. Master’s Thesis, Université du Québec à Montréal, 2014.

- 52.MiningWatch Canada. Brief: The Canadian International Institute for Extractive Industries and Development (CIIEID). Ottawa, Canada: Mining Watch Canada, http://www.miningwatch.ca/article/brief-canadian-international-institute-extractive-industries-and-development-ciieid (2014, accessed 6 January 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mackrael K. ‘Huge opportunities’ for Canadian mining industry to work in developing countries. The Globe and Mail, 19 June 2013, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/huge-opportunities-for-canadian-mining-industry-to-work-in-developing-countries/article12670581/ (accessed 6 January 2021).

- 54.University of British Columbia. CIIEID strategic partners letters of support, obtained through FOI request to UBC, no. UBC-14-078, https://miningwatch.ca/publications/2014/3/4/brief-canadian-international-institute-extractive-industries-and-development (2014, accessed 6 January 2021).