Abstract

We report herein a novel conjugation chemistry of N-terminal cysteines (NCys) that proceeds with fast kinetics and exquisite selectivity, allowing facile modification of NCys-bearing proteins in complex biological milieu. This new NCys conjugation proceeds with a thiazolidine boronate (TzB) intermediate that results from fast (k2: ~5000 M−1s−1) and reversible conjugation of NCys with 2-formylphenylboronic acid (FPBA). We have designed a FPBA derivative that upon TzB formation elicits an intramolecular acyl transfer to give N-acyl thiazolidines. In contrast to the quick hydrolysis of TzB, the N-acylated thiazolidines exhibit robust stability under physiologic conditions. The utility of the TzB mediated NCys conjugation is demonstrated by rapid and non-disruptive labeling of two enzymes. Furthermore, applying this chemistry to bacteriophage allows facile chemical modification of phage libraries, which greatly expands the chemical space amenable to phage display.

Keywords: Protein conjugation, Bioorthgonal chemisry, N-terminal cysteine, N-acylthiazolidine, Phage display

Graphical Abstract

Fast and dynamic thiazolidine boronate (TzB) formation followed by an acyl transfer reaction enables facile N-terminal cysteine modification with single digit micromolar concentrations of labeling reagents and exquisite selectivity. This utility of this reaction is demonstrated by non-disruptive labeling of enzymes as well as bacteriophage to generate chemically modified phage libraries.

Biocompatible reactions for site-specific protein modification have been heavily sought after for various applications, including protein labeling to facilitate functional studies and construction of homogenous antibody-drug conjugates as novel therapeutics. While the use of non-natural amino acids readily provides a convenient handle for protein labeling, it remains a formidable challenge to modify native proteins in a site-specific manner.[1] Towards this end, a number of peptide tags consisting of proteinogenic amino acids[2–7] have been reported to allow selective modification of tagged proteins. However, these peptide tags are typically rather large in size, and save a couple of exceptions,[8,9] require an enzyme that has to be added to the reaction and removed afterwards.

Protein modification at the N-terminus offers an appealing alternative[10–13] as it affords site specificity yet is minimally disruptive to the protein function. In particular, the unique reactivity of N-terminal cysteines (NCys) has been explored, giving rise to the native chemical ligation (NCL)[14] as well as the 2-cyanobenzothiazole (CBT) condensation chemistries[15] (Figure 1a, b). Unfortunately, these reactions are less ideal for biological applications due to slow kinetics and/or suboptimal NCys selectivity. Recently, our group[16] and the Gois group[17] independently described a novel NCys modification chemistry, in which 2-formylphenylboronic acid (2-FPBA) rapidly conjugates with an NCys to give a thiazolidino boronate (TzB) complex (Figure 1c). However, the TzB formation is dynamic with the conjugate dissociating over an hour.[16] To overcome this problem, we report herein a TzB mediated acylation reaction of NCys that gives stable conjugates while retaining the fast kinetics and superb NCys selectivity of the TzB chemistry (Figure 1d). The utility of this TzB-mediated NCys conjugation is demonstrated by the facile labeling of two model enzymes as well as bacteriophage to give chemically modified phage libraries.

Figure 1.

Reactions for selective NCys modification.

The TzB formation of NCys proceeds with a rate constant of ~5,000 M−1●s−1, faster than the NCL or CBT conjugation by several orders of magnitude.[16] The fast conjugation allows clean NCys modification with just equimolar amount of the labeling reagent. Importantly, 2-FPBA shows no reactivity to internal cysteines as the TzB conjugation is initiated with formation of iminoboronates. The reversibility of TzB formation is presumably because the lone pair of electrons on thiazolidine N can elicit reformation of the imine to eliminate the thiol. We envisioned that acylation of the thiazolidine N would disfavor this pathway to give stable conjugates. Inspired by the series of elegant work on aldehyde-mediated peptide/protein ligation chemistries,[18–21] we synthesized an acetyl ester of 2-FPBA (KL42), which we anticipated to elicit rapid TzB formation followed by intramolecular acyl transfer to give a stable thiazolidine product (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Stable NCys modification with KL42. a) Structures and nomenclatures of reagents, products and side products. b) 1H-NMR characterization data of KL42 conjugation with the model peptide CLA, showing formation of the desired conjugate KL44P1. The sample was prepared with 1mM of each reactant in a pH 7.4 buffer. c) Crystal structure of two KL44 variants prepared via KL42 conjugation with cysteamine (P2) and a cysteine-amide (P3) respectively. d) Comparison of KL44 formation kinetics at varied concentrations and pHs. The samples were prepared in phosphate buffer with concentration and pH indicated in the figure. The percentage of conversion was calculated according to the 1H-NMR data (an example dataset shown in Figure S5).

The details of KL42 synthesis are included in the Supporting Information (Scheme S1, Figure S1). It is well documented that salicylaldehyde ester undergoes fast hydrolysis in neutral aqueous solution.[22] Indeed, in our own hand, acetyl ester of salicylaldehyde hydrolyzes with a half-life (t1/2) of ~3 minutes (Figure S2). In contrast, we found KL42 hydrolyzes much more slowly giving a half-life of 2.5 hours in a pH 7.4 buffer (Figure S2). This much slowed hydrolysis can be rationalized by the fact that KL42 adopts a boroxole structure in aqueous solution, which minimizes the aldehyde hydrate assisted hydrolysis of the ester.

With KL42 in hand, we first examined its reactivity to model peptides using 1H-NMR, LC-MS and X-ray crystallography. We note that KL42 exhibited excellent solubility and readily gave millimolar solutions in aqueous buffer. When mixed with a small peptide P1 (Cys-Leu-Ala) in a neutral phosphate buffer, KL42 elicited immediate formation of a TzB conjugate KL43P1, which decreased in abundance over time to give two new molecular species (Figure 2b). LC-MS analysis of the reaction revealed a clean conversion to a product that shows the expected mass for KL44P1 (Figure S4). In 1H-NMR, the new molecular species show peaks at 6.42 and 6.36 ppm, which are characteristic of the C2 proton of a thiazolidine ring. Importantly, two peaks were observed at 1.87 and 1.93 ppm with three times of integration relative to the 6.42 and 6.36 peak respectively (Figure S5), as expected for the acetyl peaks of KL44P1. Interestingly, although KL42 is known to hydrolyze with a t1/2 of 2.5 hr, we did not see any hydrolytic product over a time course of 20 hr (Figure S5). This observation suggests that the TzB structure of KL43P1 further slows down the hydrolysis of the ester bond, presumably because the boronate in the TzB complex is less electron-withdrawing in comparison to the boronic acid in KL42.

The clean mass-spec data (Figure S3a) indicate the two molecular species observed in 1H-NMR are likely to be isomers of some sort. We attempted to crystalize the KL44P1 with no success. However, we were able to get crystal structures for two KL44 variants obtained via KL42 conjugation with cysteamine (P2) and a cysteine amide (P3) respectively (Figure 2c). As expected, both crystal structures display an N-acylated thiazolidine core. Interestingly, the cysteamine conjugate KL44P2 exhibits a cis-configuration for the newly generated amide bond, while the conjugate of P3 gives a trans amide bond. These crystal structures suggest that the KL44 amide bond could exist as a mix of cis and trans isomers, which explains the two molecular species revealed by the 1H-NMR of KL44P1. Lending further support to this assignment, 1H-NMR data indicate that KL44P2 and KL44P3 exist a pair of isomers in solution as well, although only a single isomer was seen in crystal structures (Figure S3).

Next, we tested the stability of the N-acyl thiazolidine conjugate using a fluorophore labeled peptide variant P1* with the sequence of H-CLA(Dap-FAM)-NH2. First, KL44P1* showed no degradation during LC-MS analysis (Figure S6a), while the TzB complex of P1* (KL45P1*) showed 90% dissociation under the same LC-MS conditions (Figure S6b). Furthermore, when mixed with free cysteine, KL45P1* was found to go through quick exchange (< 1 hr) to give the TzB complex of free cysteine, consistent with what we previously reported for TzB complexes. In contrast, no exchange was observed for KL44 and free cysteine (Figure S6a), lending further support to the stability of the N-acyl thiazolidine product. Using LC-MS characterization, we further tested KL44 at pH 7.4 as well as pH 5, which relevant to the weak acidic conditions seen in lysosomes. The results show little degradation of KL44 at pH 5 or 7 over 6 days (Figure S6c).

The mechanism of KL44 formation presumably involves fast and efficient TzB formation followed by an intramolecular acyl transfer reaction, which is the rate limiting step. This mechanism indicates the rate of this TzB mediated acylation should be concentration independent, thereby allowing efficient NCys conjugation with low concentrations of KL42 or its derivatives. To test this hypothesis, we comparatively analyzed the conjugation of KL42 and P1 with the reactants at 1 mM and 0.2 mM respectively. Plotting the integration over time for the characteristic 1H-NMR peaks of KL44 gave the kinetic profiles of the reactions (Figure 2d, Figure S5). Curve fitting yielded an apparent t1/2 of 2.9 hr for the 1mM reaction, and 5.9 hr for the 0.2 mM reaction. The less than two fold difference in t1/2 is consistent with the intramolecular acyl transfer being the rate limiting step. To accelerate the acyl transfer step, we explored KL42 conjugation with P1 under varied pH conditions. Excitingly, near quantitative conversion of P1 to KL44P1 was observed at pH 6 after an hour (Figure 2d). Quantitative analysis yielded an apparent t1/2 of 0.3 hr, indicating the reaction is 10 times fasters at pH 6 than pH 7.4.

To probe the general applicability of this chemistry, we comparatively examined the KL42 conjugation to additional peptides (P4–6) that have Gly, Trp and Pro following NCys respectively. Efficient conjugation was observed for all these peptides with complete conversion in 2 hr (Figure S7). Importantly, the peptide labeling was minimally affected by the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (Figure S8), showcasing the excellent biocompatibility of our NCys conjugation chemistry.

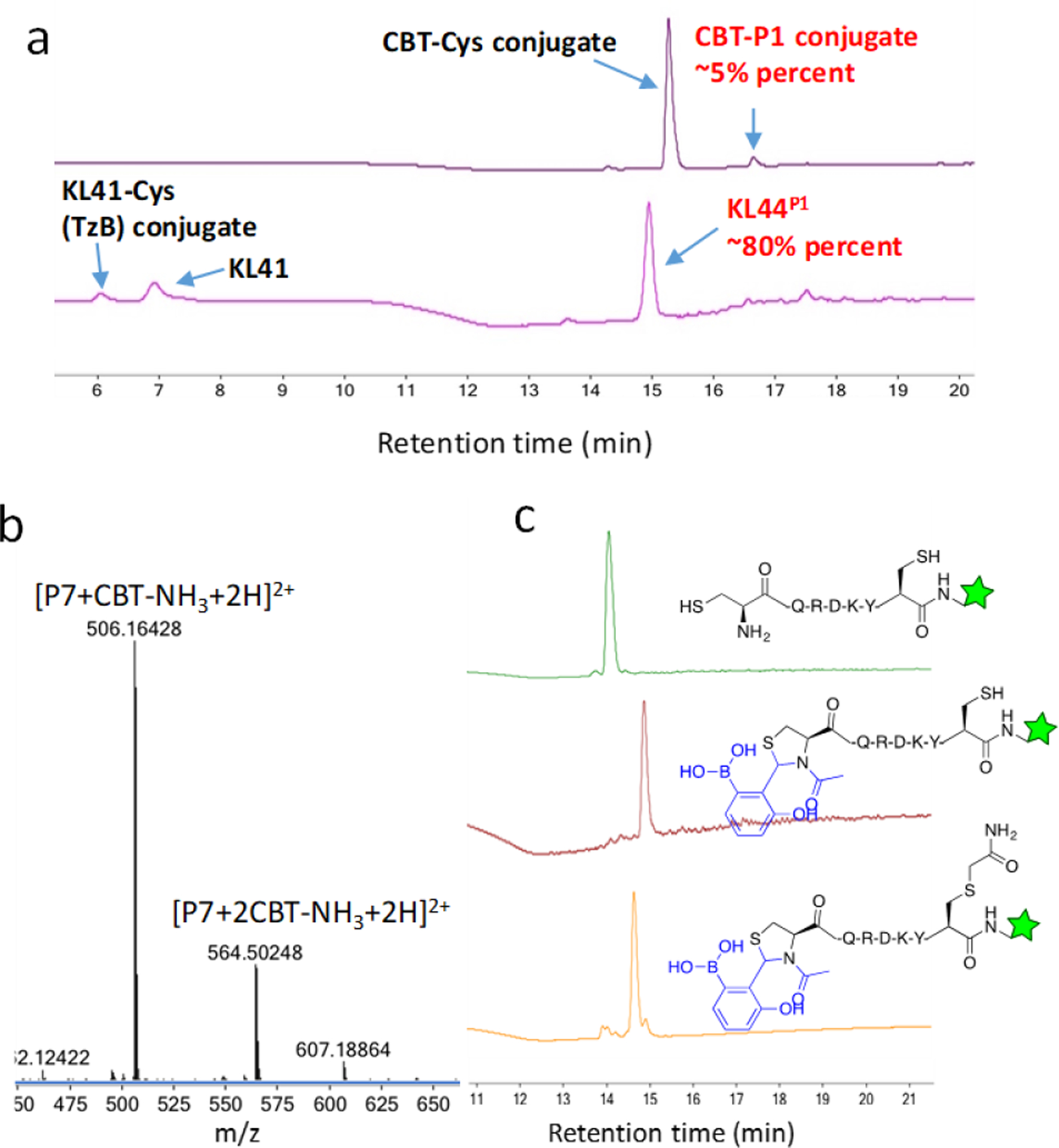

In comparison to other NCys modification chemistries (Figure 1), our TzB mediated NCys modification is advantageous for the following reasons. First, the TzB mediated NCys modification exhibits pseudo first order kinetics, allowing efficient NCys labeling with even single digit μM concentrations of the labeling reagent. For example, KL42 at 2 μM concentration elicited ~80% labeling of the peptide P1 (also at 2 μM) within just one hour (Figure 3a, KL42 hydrolysis occurred to a small extent). Under similar experimental conditions, CBT afforded only 5% of the desired product (Figure 3a), while an example thioester (acetyl ester of a water soluble thiophenol, Figure S9) elicited barely detectable peptide modification, consistent with its even slower reaction kinetics in comparison to CBT.[23] Second and perhaps more importantly, the TzB chemistry is highly specific for NCys, while CBT can elicit internal cysteine modification as well.[24] Indeed, when the model peptide P7 (H-CQRDKYC(Dap-fluorescein)-NH2) was treated with CBT, a peptide adduct with two CBT addition (−17 for loss of NH3 due to luciferin formation) was observed (Figure 3b). Further treatment of this sample with iodoacetamide (IA) failed to convert this adduct into a cysteine-alkylated product (Figure S10), consistent with the fact that the internal cysteine is masked and non-reactive. In contrast, treating P7 with KL42 yielded a single peak corresponding to the N-terminal cysteine modified product. Further treating this sample with IA resulted in clean formation of an IA-alkylated product presumably on the internal cysteine (Figure 3c). The fast kinetics and exquisite selectivity makes KL42 an ideal reagent for labeling N-terminal cysteines.

Figure 3.

Comparative studies of KL42 and CBT for NCys modification. a) LC-MS analysis showing 2 μM KL42 efficiently labels P1 over 1 hr, while under comparable conditions CBT elicited only 5% peptide modification. Note that the reactions were carried out at pH 6.0 for KL42 and 7.4 for CBT, which are the optimal pHs for these reagents respectively. The unreacted CBT was captured by free cysteine added to quench the reaction after 1hr incubation. b) Mass-spec data revealing CBT reactivity to both N-terminal and internal cysteines. The peptide P7 (50 μM) was treated with CBT (250 μM, pH 7.4) for 1 hr and then subjected to LC-MS analysis. c) Sequential labelling of NCys and an internal cysteine of a model peptide. The peptide P7 (50 μM) was treated with KL42 (250 μM, pH 6.0, 1 hr) followed by iodoacetamide (1 mM, pH 8.0, 1 hr), and then subjected to LC-MS analysis.

Encouraged by the peptide studies, we further tested the TzB mediated NCys conjugation for labeling large proteins. Towards this end, we recombinantly expressed two model proteins, azo-reductase (AzoR) and thioredoxin (Trx), whose N-terminus was engineered to carry a TEV protease cleavage site (ENLYGQC) and a factor Xa cleavage site (IEGRC) respectively. Enzymatic cleavage of these proteins exposes a cysteine residue at the N-terminus. The resulting NCys-bearing proteins (Cys-AzoR and Cys-Trx) were treated with KL42 for 2 hr and then analyzed by LC-MS. Excitingly, KL42, used at 5 or even 1 equivalent (50 and 10 μM respectively), elicited complete labeling of Cys-AzoR: LC-MS analysis revealed a single mass envelope corresponding to the postulated protein conjugate with KL42 (Figure 4a, Figure S11). No mass of the original, unlabeled Cys-AzoR was observed, indicating a clean and complete conjugation. In contrast, the thioester at 10 μM (1 equivalent) afforded marginal protein labeling (Figure S12), consistent with the results of our peptide studies (Figure S9). To expand the scope of this protein labeling protocol, we synthesized a biotin derivative of KL42, namely KL72 as shown in Figure 4b. A comparative study showed that KL72 elicited NCys modification with comparable kinetics as the parent compound KL42 (Figure S4). Mixing KL72 with Cys-AzoR showed efficient biotinylation of the protein (Figure S13). The high efficiency of AzoR biotinylation was further corroborated with a gel shift analysis,[15] in which the biotin-labeled protein primarily traveled as complexes of streptavidin on a SDS-PAGE gel (Lane 5, Figure 4c). As a control, the KL42 treated Cys-AzoR when mixed with streptavidin did not give any high-molecular-weight bands as expected (Lane 3, Figure 4c). Parallel analysis of Cys-Trx revealed highly efficient labeling of this protein by KL42 as well (Figure S14). Importantly, treating Cys-Trx with KL42 minimally affected the activity of this enzyme (Figure S15). The clean and non-disruptive labeling of Trx is quite remarkable as Trx has five functionally important cysteine residues, which are apparently not affected by KL42 treatment, lending further support to the superb selectivity of KL42 to NCys.

Figure 4.

Protein labeling via the TzB mediated NCys conjugation. a) Mass-spec data of KL42 labeled Cys-AzoR. The protein (10 μM) was treated with 1 equivalent of KL42 at pH 6.0 for 2 hr before LC-MS analysis. The insert shows the LC traces of Cys-AzoR before and after labeling. The labeling reaction gives a single mass envelope corresponding to the labeled protein. b) Structure of KL72 synthesized for NCys biotinylation. c) Gel shift analysis of Cys-AzoR biotinylation. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis without boiling with loading buffer (see SI for details). Lane 1: unmodified Cys-AzoR; lane 2: KL42 labelled Cys-AzoR; lane 3: KL42 labelled Cys-AzoR mixed with streptavidin; lane 4: KL72 labelled Cys_Azo; lane 5: KL72 labelled Cys_Azo mixed with streptavidin; lane 6: streptavidin alone. The residual non-complexed AzoR in lane 5 presumably results from the small extent of streptavidin denaturation on SDS-PAGE as evidenced by the lower band seen even in streptavidin alone (lane 6).

We envisioned that the fast and highly specific NCys conjugation chemistry could be used to modify bacteriophage to assess chemically modified phage libraries. Phage display is a powerful screening platform to allow facile discovery of peptide probes and inhibitors. However, this powerful technique has been limited to peptides composed of proteinogenic amino acids. Chemoselective and site-specific modification of bacteriophage would render phage display amenable to non-proteinogenic functionalities. To test our NCys conjugation chemistry for phage modification, we have prepared a peptide library on M13 phage that incorporates a Factor Xa cleavage site (IEGR) at the N-terminus of the pIII protein. The protease cleavage site is followed by a C(X)7C peptide library. Factor Xa cleavage proceeds efficiently as monitored by an ELISA assay (Figure S16), which is then followed by reduction of the disulfide bond to give a free NCys on the pIII protein. The resulting phage was treated with KL72 and the extent of phage biotinylation was assessed via ELISA (Figure 5a). Briefly, streptavidin was coated in wells of a 96-well plate to pull down biotinylated phage, which is then qualified using anti-M13 antibody fused to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Excitingly, the ELISA results show that KL72 elicited efficient biotinylation of the Factor Xa treated phage (Figure 5b), giving comparable readout to the positive controls in which reduced phage was treated with a biotin-iodoacetamide (BIA). Furthermore, the KL72 elicited phage pulldown can be effectively blocked by pre-treatment with KL42, which presumably modifies NCys without biotinylation. Importantly, treating the control phage (AC7C phage, no NCys) with KL72 afforded little phage pulldown as expected for the absence of NCys. Collectively, these results showcase the efficiency and specificity of KL72 for modifying bacteriophage with N-terminal cysteines. Note that the NCL chemistry has been previously applied to modify phage libraries, in which much compromised phage viability was observed presumably due to non-specific reactions.[25] In contrast, KL72 treatment did not noticeably compromise phage’s infectivity as comparable titering results were obtained for phage samples before and after KL72 treatment (see SI for details).

Figure 5.

Chemical modification of M13 phage library via TzB mediated NCys conjugation. a) Illustration the ELISA experimental design. B) ELISA results showing KL72 modifies NCys-bearing phage with high efficiency and specificity.

In summary, this contribution describes a novel conjugation chemistry for fast and highly specific NCys modification. This new NCys conjugation chemistry proceeds via rapid formation of a TzB intermediate followed by intramolecular acyl transfer to give stable N-acylthiazolidines. This enzyme-like reaction mechanism capitalizes on the fast kinetics and exquisite NCys selectivity of the TzB chemistry, which allows efficient and site-specific protein modification with low micromolar concentration of reagents. Using two model proteins, we demonstrate highly efficient and specific labeling of NCys-bearing proteins. It is important to note that little compromise of enzymatic activity was observed for the model proteins albeit our labeling reactions required an optimal pH of 6.0. Furthermore, we show that this TzB-mediated NCys modification can be applied to install non-natural functionalities to bacteriophage in a site-specific manner, presenting a powerful addition to the still very limited number of methodologies[26,27] for creating chemically modified phage libraries.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health for financial support via grants CHE-1904874 and R01GM102735.

References

- [1].Tamura T, Hamachi I, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 2782–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chen I, Howarth M, Lin W, Ting AY, Nat. Methods 2005, 2, 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Keppler A, Gendreizig S, Gronemeyer T, Pick H, Vogel H, Johnsson K, Nat. Biotechnol 2003, 21, 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].V Los G, Encell LP, McDougall MG, Hartzell DD, Karassina N, Zimprich C, Wood MG, Learish R, Ohana RF, Urh M, et al. , ACS Chem. Biol 2008, 3, 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gautier A, Juillerat A, Heinis C, Corrêa IR, Kindermann M, Beaufils F, Johnsson K, Chem. Biol 2008, 15, 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Appel MJ, Bertozzi CR, ACS Chem. Biol 2015, 10, 72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mao H, Hart SA, Schink A, Pollok BA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 2670–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Albert Griffin B, Adams SR, Jones J, Tsien RY, in Appl. Chimeric Genes Hybrid Proteins - Part B Cell Biol. Physiol (Eds.: Thorner J, Emr SD, J.N.B.T.-M. in Abelson E), Academic Press, 2000, pp. 565–578. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhang C, Welborn M, Zhu T, Yang NJ, Santos MS, Van Voorhis T, Pentelute BL, Nat. Chem 2016, 8, 120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rosen CB, Francis MB, Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Purushottam L, Adusumalli SR, Singh U, Unnikrishnan VB, Rawale DG, Gujrati M, Mishra RK, Rai V, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dai Y, Weng J, George J, Chen H, Lin Q, Wang J, Royzen M, Zhang Q, Org. Lett 2019, 21, 3828–3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen D, Disotuar MM, Xiong X, Wang Y, Chou DH-C, Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 2717–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SB, Science 1994, 266, 776–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ren H, Xiao F, Zhan K, Kim Y-P, Xie H, Xia Z, Rao J, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2009, 48, 9658–9662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bandyopadhyay A, Cambray S, Gao J, Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 4589–4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Faustino H, Silva MJSA, Veiros LF, Bernardes GJL, Gois PMP, Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 5052–5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tam JP, Miao Z, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 9013–9022. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Raj M, Wu H, Blosser SL, Vittoria MA, Arora PS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6932–6940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li X, Lam HY, Zhang Y, Chan CK, Org. Lett 2010, 12, 1724–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu H, Li X, Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 1643–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Walder JA, Johnson RS, Klotz IM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1978, 100, 5156–5159. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Saito F, Noda H, Bode JW, ACS Chem. Biol 2015, 10, 1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ramil CP, An P, Yu Z, Lin Q, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5499–5502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dwyer MA, Lu W, Dwyer JJ, Kossiakoff AA, Chem. Biol 2000, 7, 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Heinis C, Rutherford T, Freund S, Winter G, Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ng S, Jafari MR, Matochko WL, Derda R, ACS Chem. Biol 2012, 7, 1482–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.