Abstract

Activating type 1 cannabinoid (CB1) receptor decreases the particle size of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and inhibits reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). This study examined whether marijuana (MJ) use is associated with changes of RCT, and how the latter is associated with mitochondrial function and fluid cognition. We recruited 19 chronic MJ users and 20 nonusers with matched age, BMI, sex, ethnicity, and education. We measured their fluid cognition, mitochondrial function (basal and max respiration, ATP production) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, cholesterol content in serum lipoprotein fractions, enterolactone/creatinine ratio in urine as a marker for dietary polyphenol intake, and lipase activity in serum. We found that higher percentage of large HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) correlated positively, while that of small HDL-C correlated inversely, with mitochondrial function among MJ users, but correlations of the opposite directions were found among nonusers. The concentrations of large and intermediate HDL-C correlated positively with mitochondrial function and fluid cognition among MJ users, but not among nonusers. Both percentage and concentration of large HDL-C correlated positively, while those of small HDL-C correlated inversely, with amounts of daily and lifetime MJ use. In all participants, higher urinary enterolactone/creatinine ratio and lower serum lipase activity were associated with higher large HDL-C/small HDL-C ratio, implying greater RCT. This study suggests that high MJ use may compromise RCT, which is strongly associated with mitochondrial function and fluid cognition among MJ users.

Keywords: Marijuana, reverse cholesterol transport, mitochondria, cognition, polyphenol, lipase

INTRODUCTION

Cholesterol modulates the structure and function of cell membranes, and therefore its cellular content and distribution are tightly regulated (Maxfield and Tabas, 2005). Cells obtain cholesterol either by endocytosis of cholesterol-rich low-density lipoprotein (LDL), or by de novo cholesterol synthesis from acetyl-CoA. Excess cholesterol in the periphery cells is transported to the liver by high-density lipoprotein (HDL), a process known as reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) (Cuchel and Rader, 2006). The cholesterol content of HDL particles can vary over 10 folds, depending on the particle size (Rosenson et al., 2011). The nascent HDL is produced in the liver and intestine, and consists primarily of phospholipid and apolipoprotein A-1. It accepts free cholesterols from peripheral cells through the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA1 to form discoidal HDL. Lecithin-cholesterol acyl transferase (LCAT) esterifies the newly accepted free cholesterols to form the hydrophobic core of spherical small HDL particle. More free cholesterols are then transferred by ABCG1 from peripheral cells to small spherical HDL, where they are esterified by LCAT to enlarge the particle size and form intermediate and then large HDL (Zannis et al., 2006; Heinecke, 2015). The level of large HDL cholesterol (large HDL-C) correlated inversely, while that of small HDL-C correlated positively with the risk of coronary artery disease (Salonen et al., 1991; Kwiterovich, 2000), suggesting the ratio of large HDL-C/small HDL-C is a marker of the RCT ability.

RCT is regulated by type 1 cannabinoid (CB1) receptor, which predominantly expressed in the brain and peripheral tissues. For example, anti-obesity drug Rimonabant is an inverse agonist for CB1 receptor, and it upregulates the mRNA levels of various components of the RCT system, including ABCG1 and scavenger receptor B1 (Sugamura et al., 2010); as a result Ramonabant increases HDL-C level and HDL particle sizes in patients with atherogenic dyslipidemia (Despres et al., 2009). Marijuana (MJ) refers to products derived from the plant Cannabis sativa, and contains substantial amount of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is an agonist of the CB1 receptor (Sim-Selley, 2003; Morales et al., 2017). Therefore, MJ use may activate CB1 receptor, inhibit RCT, and lead to cholesterol deposition in peripheral cells.

RCT is also regulated by polyphenols, a large group of phytochemicals from plant-based diet. Polyphenols promoted RCT via upregulating the expression of ABCA1(Xia et al., 2005; Berrougui et al., 2015), ABCG1 (Uto-Kondo et al., 2010), or both (Sevov et al., 2006), possible by upregulating liver X receptor (LXR) (Burke et al., 2010). Several studies reported that MJ users tend to have lower intake of fruits and vegetables, but higher intake of fat and animal products than nonusers do (Farrow et al., 1987; Smit and Crespo, 2001; Arcan et al., 2011; Hahn et al., 2014), and such dietary pattern may also compromise RCT and facilitate cholesterol deposition in the peripheral cells.

Mitochondria (mt) are cholesterol-poor organelles, and only contain 0.5% - 3% of the cholesterol found in plasma membranes. Cholesterol overload in mt is associated with compromised mt function (Colell et al., 2003; Ribas et al., 2016). We previously reported that mt function closely correlated with fluid cognition among chronic MJ users (Panee et al., 2018). We are interested in understanding the role of cholesterol homeostasis in the regulation of mt function and fluid cognition during chronic MJ use. Here we report our initial investigation on how blood cholesterol is correlated with mt function, fluid cognition, urinary enterolactone/creatinine ratio (a marker for dietary polyphenol intake), and blood lipase activity (contribute to fat digestion) in chronic MJ users and nonuser controls.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS, MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

We have published the detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria previously (Panee et al., 2018). Briefly, adult participants were recruited locally in Honolulu, Hawaii. All MJ users used MJ daily for at least 3 years, and detailed substance use history was recorded to calculate the amounts of daily and lifetime cumulative MJ use. All nonusers had less than 10 times lifetime MJ use, and had not used MJ in the past 6 months. Urine toxicological test was conducted to confirm the self-reported MJ use status. The characteristics of the study participants were published before (Panee et al., 2018), and are again provided in Table 1 for quick reference. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the Human Studies Program of the University of Hawaii.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

| Marijuana Users (n=19) | Non-Users (n=20) | p value (Chi-square or t-test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.0 (22.0-32.0) | 27.0 (21.5-36.0) | 0.94 |

| Sex (Female/Male) | 7/12 | 7/13 | 0.90 |

| % Race (Asian/ Black / Mixed / Pacific Islander/ White) | 10.5 / 0 / 26.3 / 10.5 / 52.6 | 30 / 0 / 20 / 0 / 50 | 0.25 |

| % Ethnicity (Hispanic / Non-Hispanic) | 26.3 / 73.7 | 20 / 80 | 0.64 |

| Education (years) | 15.0 (12.0-16.0) | 14.8 (14.0-16.5) | 0.29 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 23.6 (21.7-27.9) | 26.3 (23.1-29.7) | 0.42 |

| Waist/Hip circumference ratio | 0.85 (0.82-0.88) | 0.86 (0.82-0.92) | 0.88 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 36.5 (33.5-38.0) | 36.5 (34.5-39.0) | 0.67 |

| Substance Use Patterns | |||

| Marijuana (MJ) Use | |||

| # used MJ in past month (%) | 19/19 (100%) | ||

| Age of first MJ use (year) | 16.0 (15.0-19.0) | ||

| Daily average MJ used (g) | 1.0 (0.5-2.0) | ||

| Duration of MJ use (year) | 7.5 (4.0-11.0) | ||

| Total lifetime MJ used (kg) | 2.7 (1.5-4.9) | ||

| Alcohol Use | |||

| # used alcohol in past month (%) | 17/19 (90%) | 12/20 (60%) | 0.035 |

| Age of first alcohol use (year) | 18.5 (16.0-22.0) | 21.0 (20.0-21.0) | 0.043 |

| Daily average alcohol used (ml) | 7.7 (2.4-13.1) | 1.6 (0.4-7.3) | 0.061 |

| Duration of alcohol use (year) | 9.0 (4.0-11.0) | 2.0 (1.0-8.0) | 0.091 |

| Alcohol use abstinence (day) | 4.0 (1.0-9.0) | 14.0 (4.0-30.0) | 0.14 |

| Lifetime alcohol used (L) | 20.0 (9.8-33.3) | 0.6 (0.2-20.1) | 0.074 |

| Tobacco Use | |||

| # used tobacco in past month (%) | 3/19 (16%) | 3/20 (15%) | 0.38 |

| Age of first tobacco use (year) | 16.0 (15.0-18.0) | 29.0 (26.0-36.0) | 0.0002 |

| Daily average nicotine smoked (mg) | 0 (0-68.2) | 0 (0-18.0) | 0.98 |

| Duration of tobacco use (year) | 0 (0-12.0) | 0 (0-1.0) | 0.036 |

| Nicotine abstinence (day) | 7.0 (0-730.0) | 11.0 (0-62.0) | 0.86 |

| Lifetime nicotine used (g) | 0 (0-196.6) | 0 (0-39.3) | 0.55 |

Data are shown in number, %, or Median (Interquartile Range).

Preparation of serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

Blood was collected from each participant via venipuncture in early morning (7 am- 10 am) after 12-hour fasting. Serum and PBMCs were prepared from whole blood within 1 hour of blood draw (Panee et al., 2018). Briefly, serum was prepared by centrifuging (1,200 x g, 10 min) whole blood that were clotted at room temperature, and stored at −80°C until assay. PBMCs were prepared from whole blood collected in EDTA-coated tubes using the Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation (HANC, 2014). Cells were dispersed in cryopreservation medium and stored in liquid nitrogen until assay.

Fluid cognition assessment

Five tests were selected from the Cognition Battery of the NIH Toolbox® to measure the fluid cognition (Heaton et al., 2014): (1) Flanker Task, measuring both inhibitory control and attention; (2) List Sorting Task, assessing working memory; (3) Dimensional Change Card Sort Test, evaluating executive function; (4) Picture Sequence Memory Test, assessing episodic memory; (5) Pattern Comparison Test, measuring speed of information processing. The Fluid Cognition Composite score was calculated by the NIH Toolbox® based on the scores of these 5 tests. All tests were conducted by the same experimenter in early morning, 15 min after the blood draw. All MJ users were required to abstain from MJ for 12 hours before the tests, to avoid acute effect of MJ use on cognitive performance.

PBMC mt respiration measurements

PBMC viability was determined using acridine orange/propidium iodide staining. PBMCs were seeded at a density of 5.0e5 live cells per well in duplicate on cell culture plates treated with poly-L-lysine. PBMCs’ mt oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was assessed using the Mito Stress test and Seahorse XFe96 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), which uses high-throughput oximetry to simultaneously measure OCR and extracellular acidification (ECAR) rates as we have described (Takemoto et al., 2017).

Serum cholesterol Lipoprint fractionation

Lipoprotein fractions and subfractions were analyzed by linear polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis method using the Lipoprint LDL and HDL System (Quantimetrix Corporation, Redondo Beach, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, serum samples were run on high-resolution 3% polyacrylamide gel tubes and analyzed by the ScanPotter software. The computerized method identified and quantitatively scored the resolved LDL and HDL subfractions. The Lipoprint LDL System is able to segregate LDL fraction into 7 subfractions, while the Lipoprint HDL test can resolve up to 10 subfractions of HDL which are grouped into three main subclasses: HDL 1-3 represent the Large HDL, HDL 4-7 represent the Intermediate HDL, and the HDL 8-10 represent the Small HDL.

Measurement of serum lipase activity

Serum lipase activity was measured using a Quantichrom™ Lipase Assay Kit (Bioassay Systems, Hayward, CA), based on an improved dimercaptopropanol tributyrate method.

Quantification of enterolactone/creatinine ratio in urine

Random urine samples were collected before the blood draw, and stored at −80°C until assay. Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry and a Cobas MiraPlus clinical autoanalyzer with a kit from Randox were used to quantitate urinary enterolactone and creatinine concentrations, respectively, as described before (Franke et al., 2009)(Franke et al., 2002). The ratio of enterolactone/creatinine was calculated as a urinary marker for dietary polyphenol intake by considering urine volume through adjustment for creatinine levels (Hernandez et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2015).

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were conducted to compare variables between groups (e.g., user vs. nonuser), with Student’s t-test for normally distributed outcomes, and Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed outcomes. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) based on linear models were conducted to evaluate additive main effects and interaction effects of a set of covariates (e.g., MJ use status) on an outcome variable of interest. For covariate that showed a significant group interaction on the response variable based on ANCOVA analysis, group specific correlation analysis was performed and the association visualized using interaction plots. The Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to quantify the strength of linear associations. A p-value (p) ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant, while 0.05 < p ≤0.1 was considered as a trend of significance. All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the two groups had similar distribution in race, ethnicity, and sex ratio, and had comparable age, years of education, BMI, waist/hip ratio, and neck circumference. Compared with nonusers, MJ users had 30% higher past-month alcohol use rate (p=0.035), had used tobacco for 4 years longer (p=0.036), and were 3.3 (p=0.043) and 14.6 (p=0.0002) years younger when first used alcohol and tobacco, respectively. However, the two groups had similar cumulative lifetime alcohol and tobacco use. Notably the study cohort was relatively young, with a median age of 28 years.

Large and intermediate HDL-C inversely correlated with age and BMI

MJ users and nonusers had similar levels of total cholesterol, total HDL-C (and its fractions large, intermediate, and small HDL-C), and total nonHDL-C (and its fractions LDL, IDL, and VLDL-C) in fasting blood (Table 2). Regardless of MJ status, age had strong inverse correlation with total HDL-C, particularly large and intermediate HDL-C (Table 3). Similarly, BMI also had strong inverse correlations with total HDL-C, particularly large and intermediate HDL-C (Table 3).

Table 2.

Serum cholesterol levels in marijuana users and nonusers.

| Marijuana Users (n=19) | Nonusers (n=20) | p value (t-test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 245.4 (219.6, 271.1) | 230.6 (202.1, 259.1) | 0.43 |

| Total HDL-C (mg/dl) | 79.3 (66.3, 92.2) | 73.2 (58.8, 87.5) | 0.51 |

| Large HDL-C (mg/dl) | 22.9 (16.0, 29.9) | 20.2 (13.3, 27.1) | 0.56 |

| Intermediate HDL-C (mg/dl) | 39.9 (33.9, 45.9) | 36.6 (29.4, 43.7) | 0.46 |

| Small HDL-C (mg/dl) | 16.5 (13.7, 19.4) | 16.4 (12.3, 20.4) | 0.94 |

| Large HDL-C/Small HDL-C | 1.6 (0.9, 2.3) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.2) | 0.91 |

| Total nonHDL-C (mg/dl) | 165.9 (149.9, 182.0) | 157.4 (140.6, 174.1) | 0.44 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 62.5 (55.5, 69.6) | 56.4 (48.4, 64.3) | 0.23 |

| IDL-C (mg/dl) | 60.7 (53.4, 68.1) | 57.0 (49.5, 64.5) | 0.46 |

| VLDL-C (mg/dl) * | 42.7 (37.6, 47.8) | 44.0 (35.6, 52.4) | 0.78 |

Mean (95% confidence interval) are shown.

Table 3.

Correlations of serum cholesterol levels with age and BMI

| All participants (n=39) | Age (Year) | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|---|

| Total HDL-C (mg/dl) |

r=−0.57 p=0.0001 |

r=−0.49 p=0.0015 |

| Large HDL-C (mg/dl) |

r=−0.54 p=0.0004 |

r=−0.47 p=0.0027 |

| Intermediate HDL-C (mg/dl) |

r=−0.60 p<0.0001 |

r=−0.45 p=0.0038 |

| Small HDL-C (mg/dl) | r=−0.055 p=0.74 |

r=−0.15 p=0.35 |

| Total nonHDL-C (mg/dl) |

r=−0.40 p=0.011 |

r=0.016 p=0.92 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) |

r=−0.35 p=0.029 |

r=0.11 p=0.49 |

| IDL-C (mg/dl) |

r=−0.39 p=0.013 |

r=−0.13 p=0.43 |

| VLDL-C (mg/dl) | r=−0.14 p=0.38 |

r=0.050 p=0.76 |

p and r of Pearson correlation are shown.

Large HDL-C inversely and small HDL-C positively correlated with daily and lifetime MJ use

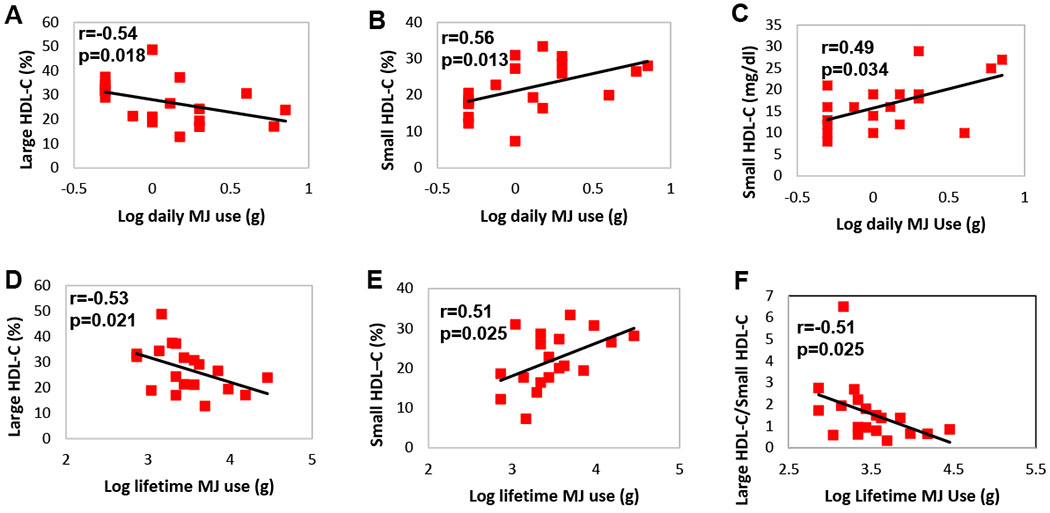

Among MJ users, those who had greater amount of daily use of MJ (log transformed) also had lower percentage of large HDL-C (Fig. 1A), but higher percentage (Fig. 1B) and higher concentration (Fig. 1C) of small HDL-C. Similarly, cumulative lifetime MJ use (log transformed) also inversely correlated with percentage of large HDL-C (Fig. 1D), but positively correlated with percentage of small HDL-C (Fig. 1E) and ratio of large HDL-C/small HDL-C (Fig. 1F). NonHDL-C did not correlate with daily or lifetime MJ use. These results imply that chronic MJ use is associated with compromised RCT ability.

Figure 1. Correlations between marijuana (MJ) use and serum cholesterol distribution in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) fractions.

Log transformed daily MJ use inversely correlated with percentage of large HDL cholesterol (large HDL-C) (A), but positively correlated with the percentage (B) and concentration (C) of small HDL-C. Log transformed lifetime cumulative MJ use inversely correlated with percentage of large HDL-C (D), positively correlated with percentage of small HDL-C (E), and inversely correlated with the ratio of large HDL-C/ small HDL-C (F). Correlation coefficient and p value of Spearman correlation are shown.

Large and intermediate HDL-C positively and small HDL-C inversely correlated with mitochondrial function in MJ users

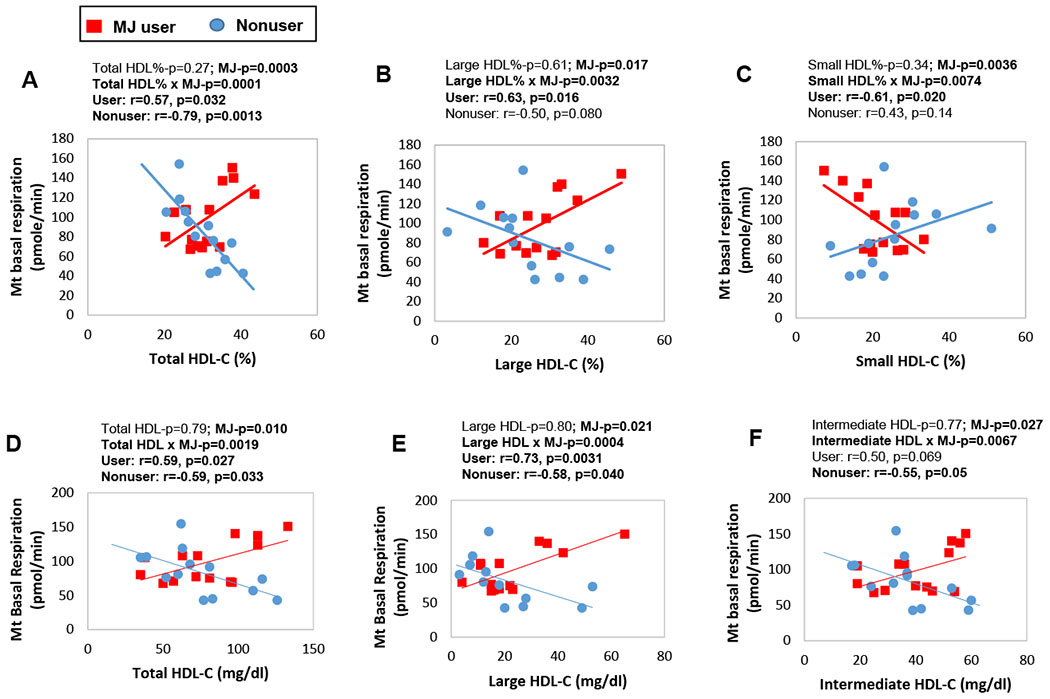

We evaluated the relationships between cholesterol fractions and mt function in PBMCs. Percentage of total HDL-C correlated positively with mt basal respiration rate among MJ users, but inversely among nonusers, with MJ use status as a strong moderator (pinteraction=0.0001, Fig. 2A). Similar results were found for percentage of large HDL-C (pinteraction=0.0032, Fig. 2B), and concentrations of total, large, and intermediate HDL-C (pinteraction=0.0019, 0.0004, and 0.0067, respectively, Figs. 2D–F). The percentage of small HDL-C correlated inversely with mt basal respiration among MJ users, but not among nonusers, with MJ use status as a significant moderator (pinteraction=0.0074, Fig. 2C). In addition to basal mt respiration rate, we also measured maximal mt respiration rate and ATP production rate to evaluate mt function in PBMCs. Supplementary Figure 1 shows that, similar to results presented in Fig 2, MJ use status moderated the relationships between mt ATP production and percentages of total, large and small HDL-C, as well as the relationships between mt maximum respiration and percentage of total HDL-C. Furthermore, the concentrations of total, large and small HDL-C also interacted or had a trend to interact with MJ use status on both ATP production and maximum mt respiration rate. NonHDL-C did not interact with MJ use status on mt function. These results demonstrate that higher levels of large and intermediate HDL-C (implying greater RCT ability) benefit mt function among MJ users, but not among nonusers.

Figure 2. Marijuana (MJ) use status moderated the correlations between fractions of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and mitochondrial (mt) basal respiration rate in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

MJ use status significantly moderated the relationships of mt basal respiration rate with (A) percentage of total HDL-C, (B) percentage of large HDL-C, (C) percentage of small HDL-C, (D) concentration of total HDL-C, (E) concentration of large HDL-C, and (F) concentration of intermediate HDL-C. The moderating effect of MJ use status was determined by two-way ANOVA, and post hoc Pearson correlation was used to evaluate the correlations between the variables in each study group. Bold fond indicates statistical significance.

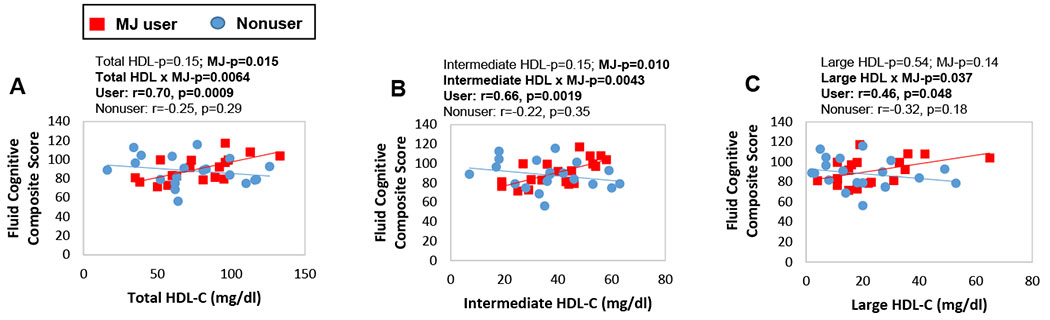

Large and intermediate HDL-C positively correlated with fluid cognition in MJ users

Among MJ users, those who had higher concentration of total HDL-C also had greater fluid cognitive composite score, but such relationship was not found among nonusers, thus MJ use status was a significant moderator (pinteraction=0.0064, Fig. 3A). When HDL-C fractions were examined individually, we found intermediate HDL-C most significantly interacted with MJ status (pinteraction=0.0043, Fig. 2B), followed by large HDL-C (pinteraction=0.037, Fig. 2C). Concentration of small HDL-C, and percentages of nonHDL-C and its fractions did not interact with MJ use status on fluid cognition. We further examined the relationship between cholesterol fractions and the 5 subdomains of fluid cognition. Supplementary Figure 2 shows that concentrations of total, large and intermediate HDL-C interacted consistently with MJ use status on executive function measured by the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task. These results show that higher levels of large and intermediate HDL-C (implying greater RCT ability) benefit fluid cognition (particularly executive function) among MJ users, but not among nonusers.

Figure 3. Marijuana (MJ) use status moderated the correlations between fractions of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and fluid cognition composite score.

MJ use status significantly moderated the relationships of fluid cognition composite score with (A) concentration of total HDL-C, (B) concentration of intermediate HDL-C, and (C) concentration of large HDL-C. The moderating effect of MJ use status was determined by two-way ANOVA, and post hoc Pearson correlation was used to evaluate the correlations between the variables in each study group. Bold fond indicates statistical significance.

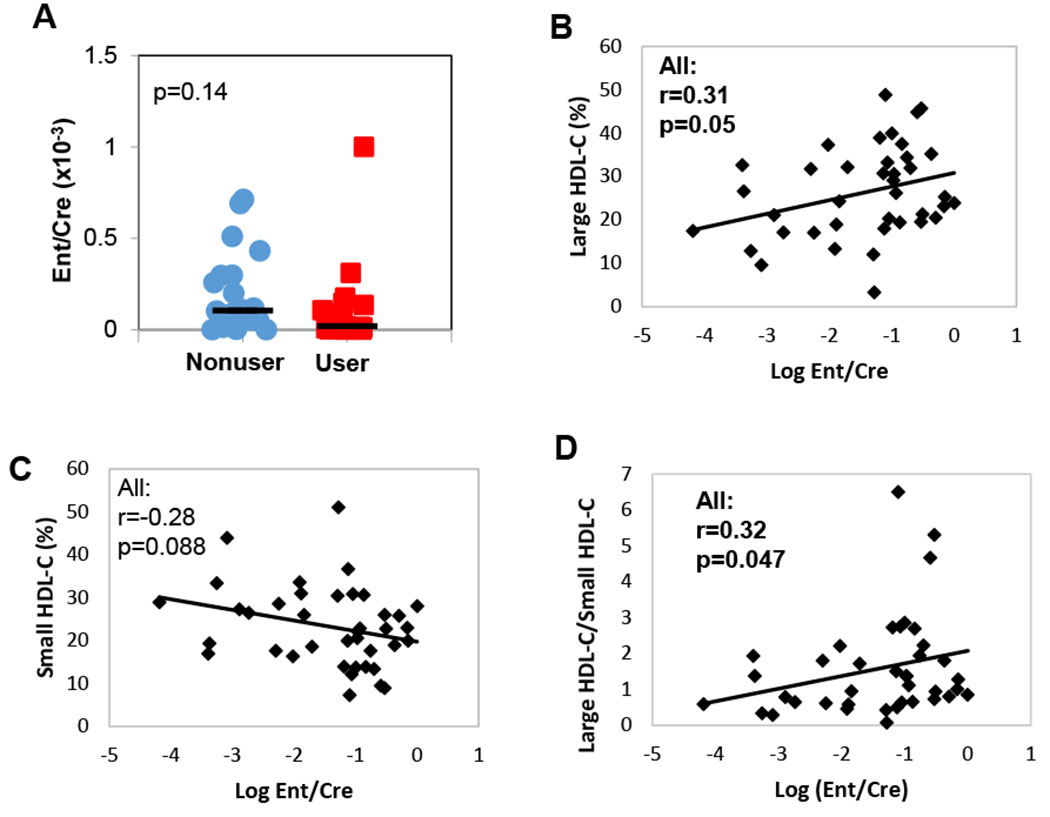

Urinary marker for dietary polyphenol intake positively correlated with large HDL-C and inversely correlated with small HDL-C in all participants

We measured the concentrations of enterolactone and creatinine in randomly collected urine samples, and used the ratio of enterolactone:creatinine (Ent/Cre) as a marker of dietary polyphenol intake (Hernandez et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2015). The median (interquartile) of the Ent/Cre ratio was 1.9e-5 (5.0e-6, 1.4e-4) for MJ users, and 1.0e-4 (5.2e-5, 3.0e-4) for nonusers (Fig. 4A). Thus MJ use was associated with an 80% decrease in Ent/Cre ratio (p=0.14, U-test), suggesting that MJ user tended to have lower dietary polyphenol intake, thus lower consumption of plant-based foods, than nonusers. Regardless of MJ use status, Ent/Cre ratio (log transformed) positively correlated with percentage of large HDL-C (Fig. 4B) and ratio of large HDL-C/small HDL-C (Fig. 4D), and had a trend to inversely correlate with percentage of small HDL-C (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that higher amount of dietary intake of polyphenols improves RCT ability, regardless of MJ use status.

Figure 4. Ratio of Enterolactone/Creatinine (Ent/Cre) in random urine samples and its correlations with fractions of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).

The Ent/Cre ratio decreased by 80% in marijuana (MJ) users compared with nonusers (A), individual data point and median of each group are shown. Regardless of MJ use status, the log transformed Ent/Cre ratio positively correlated with the percentage of large HDL-C (B), had a trend to inversely correlate with percentage of small HDL-C (C), and positively correlated with the ratio of large HDL-C/small HDL-C (D). U-test was used to evaluate the group difference of Ent/Cre ratio in Panel A, Pearson correlation was used to assess the correlations between variables in Panels B-D. Bold fond indicates statistical significance.

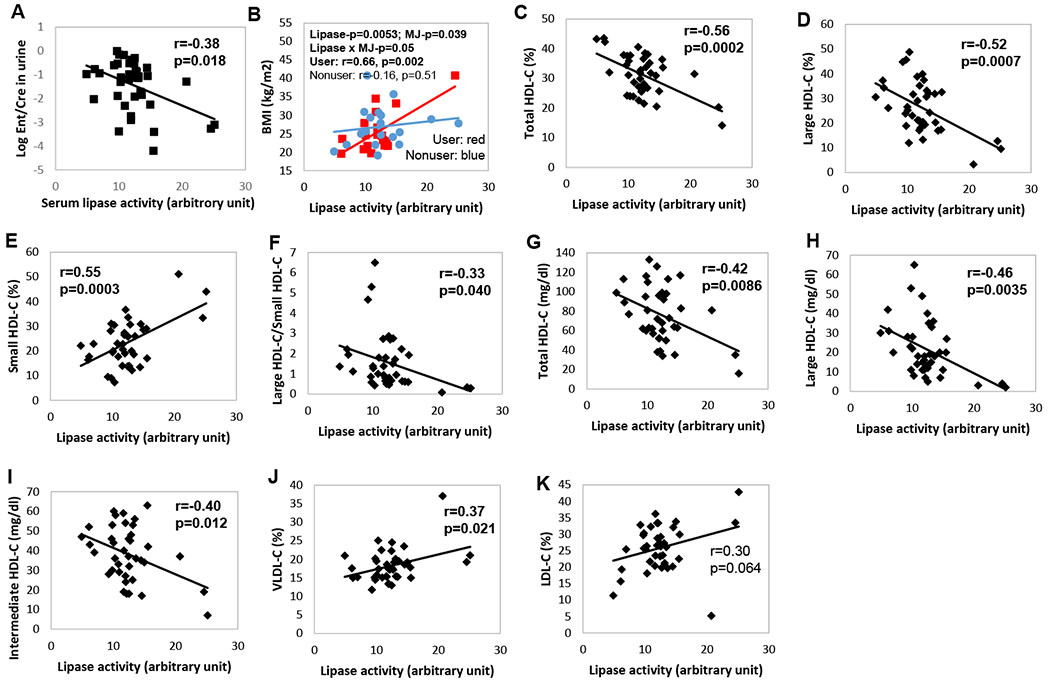

Serum lipase activity inversely correlated with large and intermediate HDL-C and positively correlated with small HDL-C in all participants

MJ user and nonusers had similar levels of serum lipase activity. Regardless of MJ use status, subjects had lower Ent/Cre ratio in the urine also had higher lipase activity in serum (p=0.018, Fig. 5A), implying that lipase secretion may be regulated by dietary content. Lipase activity positively correlated with BMI among MJ users, but not among nonusers, with MJ use status as a (weak) moderator (pinteraction=0.05, Fig. 5B). Regardless of MJ status, lipase activity positively correlated with percentage of small HDL-C (Fig. 5E), and inversely correlated with percentages of total and large HDL-C (Figs. 5C, 5D), and ratio of large HDL-C/small HDL-C (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, lipase activity also inversely correlated with concentrations of total, large, and intermediate HDL-C (Figs. 5G–5I), and positively correlated with percentage of VLDL-C (Fig. 5J) and had a trend to positively correlated with percentage of LDL-C (Fig. 5K). These results show that higher serum lipase activity decreases RCT ability.

Figure 5. Serum lipase activity and its correlations with urinary Enterolactone/Creatinine (Ent/Cre) ratio, fractions of high-, low-, and very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C, LDL-C, and VLDL-C, respectively).

Serum lipase activity inversely correlated with Ent/Cre ratio in the urine (A). Marijuana (MJ) use status was a (weak) moderator to the correlation between serum lipase activity and BMI (B). Regardless of MJ use status, serum lipase activity inversely correlated with percentages of total HDL-C (C) and large HDL-C (D), correlated with percentage of small HDL-C (E) and inversely correlated with the ratio of large HDL-C/small HDL-C (F). Serum lipase activity also inversely correlated with the concentrations of total (G), large (H) and intermediate (I) HDL-C, inversely correlated with the percentage of VLDL-C (J), and had a trend to inversely correlate with percentage of LDL-C (K). In Panel A, t-test was used to evaluate the group difference of serum lipase activity. In Panel B, the moderating effect of MJ use status was assessed by two-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Pearson correlation. Correlations in Panels C-K were evaluated using Pearson correlation. Bold fond indicates statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

This pilot study demonstrated that (1) among chronic MJ users, higher daily and cumulative MJ uses were associated with lower RCT ability; regardless of MJ use status, lower dietary intake of polyphenols and higher serum lipase activity were both associated with lower RCT ability. (2) Higher levels of large and intermediate HDL-C (implying greater RCT ability) were associated with both better mt function and superior fluid cognition among MJ users, but not among nonusers. Thus, proper RCT function has a significant role in maintaining general and cognitive health among chronic MJ users.

Marijuana and blood cholesterol

The reported effects of MJ use on blood cholesterol levels remain controversial. An earlier study of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) found similar blood HDL-C levels in adult MJ users and nonusers (n=3,617) (Rodondi et al., 2006). Two studies also compared blood HDL-C levels among nonusers, and current and past MJ users based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The first study (n=4,657) found no group differences (Penner et al., 2013); and the second study (n=8,478), after stratifying the data by sex, found both current and past male MJ users, and past female MJ users, had higher HDL-C levels than their nonuser counterparts (Vidot et al., 2016). Another study focused on African American adults (n=100), and found a trend of difference in total cholesterol levels among current MJ users, past MJ users, and nonusers (Racine et al., 2015). These studies implicate that sex and race are important factors to consider when investigate the effect of MJ use on blood cholesterol. Our study had a small sample size (n=39), and therefore we were unable to stratify the data by sex or race. The finding that MJ users and nonusers had similar blood cholesterol levels in our study should be considered together with its sample size limitation.

Marijuana and distribution of HDL fractions

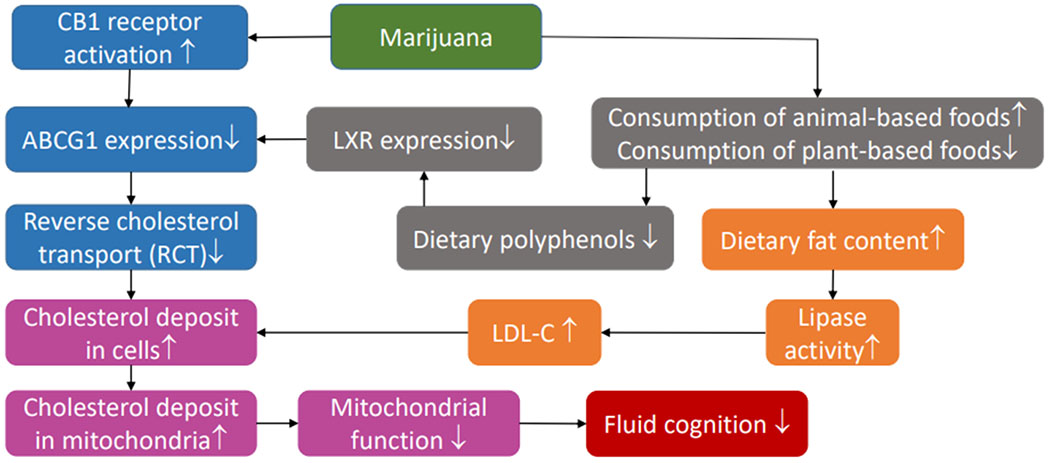

Our data showed that greater amount of cumulative MJ use was associated with decreased size of HDL particles (i.e., lower ratio of large HDL-C/small HDL-C), thus long-term MJ use likely to compromise RCT. ABCG1 is a critical transporter that mediates the efflux of excess cholesterol from peripheral cells to small HDL by altering cholesterol distribution on the cell membranes (Nakamura et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2004; Vaughan and Oram, 2005), and its expression was upregulated by CB1 receptor antagonism (Sugamura et al., 2010). We hypothesize that MJ use activates CB1 receptor, downregulates ABCG1 expression, decreases cholesterol transport from peripheral cells to small HDL, and thus compromise RCT (blue boxes in Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Hypothetical mechanistic pathways that link marijuana use with reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), mitochondrial function, and fluid cognition.

Mitochondria and Cholesterol

Mt are cholesterol-poor organelles, and maintaining cholesterol homeostasis in mt is critical for proper mt function (Martin et al., 2016). Cholesterol overload in mt increases membrane microviscosity and impaires mt permeability transition (Colell et al., 2003); it also compromises mt oxidative phosphorylation, and facilitates apoptosis in non-cancerous cells (García-Ruiz et al., 2017). Furthermore, mt cholesterol overload blocks the uptake of 2-oxoglutarate, a glutathione (GSH, antioxidant) carrier, leading to GSH depletion and oxidative stress in mt (Coll et al., 2003). We further hypothesize that compromised RCT increases cholesterol deposit in peripheral cells, which leads to cholesterol overload in mt membranes and results in mt dysfunction (purple boxes in Fig. 6).

Dietary polyphenol intake and cholesterol distribution

Several studies found that people who used MJ tended to have lower intake of fruits and vegetables, but higher intake of fat and animal products (Farrow et al., 1987; Smit and Crespo, 2001; Arcan et al., 2011; Hahn et al., 2014). Our study used urinary enterolactone/creatinine (ent/cre) ratio as a marker for plant-based food consumption, and found an 80% decrease (p=0.14) in MJ users compared to nonusers. Enterolactone is produced by intestinal bacteria from plant lignan, which is a large group of plant polyphenols. Lignan in flaxseed decreased the ratio of LDL-C/HDL-C in hypercholesterolemic men (Fukumitsu et al., 2010), and lowered levels of total, LDL, and oxidized LDL cholesterols in healthy adults (Almario and Karakas, 2013). Polyphenols found in grape seeds, including gallic acid, catechin, and epicatechin, inhibited pancreatic cholesterol esterase, and possibly delayed cholesterol absorption (Ngamukote et al., 2011). Other polyphenols promoted RCT via upregulating the expression of ABCA1(Xia et al., 2005; Berrougui et al., 2015), ABCG1 (Uto-Kondo et al., 2010), or both (Sevov et al., 2006), possible via the upregulation of liver X receptor (LXR) (Burke et al., 2010). In line with the prior studies, we found that higher urine ent/cre ratio was associated with higher RCT ability, as implicated by higher large HDL-C/ small HDL-C ratio. Thus in addition to activating CB1 receptor, MJ use may also downregulate ABCG1 and ABCA1 expression via lowering dietary polyphenol intake and inhibiting LXR expression, which further compromises RCT (grey boxes in Fig. 6).

Serum lipase and cholesterol distribution

Pancreas is the primary source of serum lipase, which converts triglycerides to monoglycerides and free fatty acids. We found that lower consumption of plant-based foods (marked by lower Ent/Cre ratio) was associated with higher serum lipase activity, possible because lipase is secreted in response to dietary content. We also found higher lipase activity was associated with greater BMI among MJ users, but not among nonusers. Because MJ users tend to consume more animal-based foods, which have higher fat content than plant-based foods, higher lipase activity leads to more complete digestion of the fats, thus greater body weight gain. Another finding is that, regardless of MJ use status, higher serum lipase activity was associated with lower RCT ability (e.g., lower ratio of large HDL-C/small HDL-C), and higher percentages of VLDL-C and LDL-C. It has been shown that dietary intake of fats from animal products substantially increases LDL-C level in the circulation (Ridlon et al., 2013; Chiu et al., 2016), which may facilitate LDL-C endocytosis and elevate cholesterol load in peripheral cells (orange boxes in Fig. 6).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. (1) This is a pilot study with relatively small sample size, and the mt function was measured only in ~70% of the participants due to limited amount of PBMCs (n=13 per group). The preliminary results generated from this study need further validation in larger scale follow-up studies. (2) The individual p values were not corrected for multiple comparisons, which may lead to a higher probability of type I error. (3) The small sample size did not allow mediation analysis that may depict the causal relationships among serum cholesterol distribution, mt function, and fluid cognition. (4) All MJ users in this study used MJ daily, and the results obtained from this population may not be generalizable to occasional recreational MJ users. (5) No significant group differences (user vs. nonuser) were detected among the major parameters measured in this study, likely due to the small sample size and large inter-individual variance, or possibly biphasic effect of MJ use on some of the parameters. (6) The effects of MJ use on RCT and mt cholesterol deposition remain hypothetical, and are to be tested in future studies.

Summary

This study highlighted the strong correlations of large HDL-C and intermediate HDL-C with mt function and fluid cognition among chronic daily MJ users, and demonstrated that higher amounts of daily and cumulative MJ use were associated with lower RCT. We also showed that lower dietary polyphenol intake and higher serum lipase activity all associated with lower RCT, regardless of MJ use status.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Greater amount of cumulative marijuana use is associated with smaller size of HDL

Smaller size of HDL is associated with lower mitochondrial activity and lower fluid cognition in chronic marijuana users, but not in nonusers

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Linda Chang for her guidance and support during the phases of participant recruitment and evaluation, and sample collection. We thank Ms. Kristen Ewell for her assistance in mitochondrial functional analyses. This study was sponsored by the RMATRIX-II Pilot Projects Program from the John A Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii (NIH/DHHS grant number U54MD007584) to JP, and other NIH grants including P30 CA71789 to AAF, R01HL108249 to OS, and P20 GM113134 to MG and OS.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors reported no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Almario RU, Karakas SE (2013) Lignan content of the flaxseed influences its biological effects in healthy men and women. J Am Coll Nutr 32:194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcan C, Kubik MY, Fulkerson JA, Hannan PJ, Story M (2011) Substance use and dietary practices among students attending alternative high schools: results from a pilot study. BMC public health 11:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrougui H, Ikhlef S, Khalil A (2015) Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols Promote Cholesterol Efflux and Improve HDL Functionality. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015:208062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke MF, Khera AV, Rader DJ (2010) Polyphenols and cholesterol efflux: is coffee the next red wine? Circ Res 106:627–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S, Bergeron N, Williams PT, Bray GA, Sutherland B, Krauss RM (2016) Comparison of the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet and a higher-fat DASH diet on blood pressure and lipids and lipoproteins: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 103:341–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colell A, Garcia-Ruiz C, Lluis JM, Coll O, Mari M, Fernandez-Checa JC (2003) Cholesterol impairs the adenine nucleotide translocator-mediated mitochondrial permeability transition through altered membrane fluidity. J Biol Chem 278:33928–33935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll O, Colell A, Garcia-Ruiz C, Kaplowitz N, Fernandez-Checa JC (2003) Sensitivity of the 2-oxoglutarate carrier to alcohol intake contributes to mitochondrial glutathione depletion. Hepatology 38:692–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuchel M, Rader DJ (2006) Macrophage reverse cholesterol transport: key to the regression of atherosclerosis? Circulation 113:2548–2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despres JP, Ross R, Boka G, Almeras N, Lemieux I, AD-L Investigators (2009) Effect of rimonabant on the high-triglyceride/low-HDL-cholesterol dyslipidemia, intraabdominal adiposity, and liver fat: the ADAGIO-Lipids trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29:416–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow JA, Rees JM, Worthington-Roberts BS (1987) Health, developmental, and nutritional status of adolescent alcohol and marijuana abusers. Pediatrics 79:218–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke AA, Murphy SP, Le Marchand L, Zheng W, Custer LJ (2002) Liquid chromatographic analysis of dietary phytoestrogens including isoflavonoids, flavonoids and lignans in foods and human body fluids. J Nutr 132. [Google Scholar]

- Franke AA, Halm BM, Kakazu K, Li X, Custer LJ (2009) Phytoestrogenic isoflavonoids in epidemiologic and clinical research. Drug Test Anal 1:14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumitsu S, Aida K, Shimizu H, Toyoda K (2010) Flaxseed lignan lowers blood cholesterol and decreases liver disease risk factors in moderately hypercholesterolemic men. Nutr Res 30:441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Ruiz C, Ribas V, Baulies A, Fernández-Checa JC (2017) Mitochondrial Cholesterol and the Paradox in Cell Death. Handb Exp Pharmacol 240:189–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn LA, Galletly CA, Foley DL, Mackinnon A, Watts GF, Castle DJ, Waterreus A, Morgan VA (2014) Inadequate fruit and vegetable intake in people with psychosis. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry 48:1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Akshoomoff N, Tulsky D, Mungas D, Weintraub S, Dikmen S, Beaumont J, Casaletto KB, Conway K, Slotkin J, Gershon R (2014) Reliability and validity of composite scores from the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery in adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS 20:588–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinecke JW (2015) Small HDL promotes cholesterol efflux by the ABCA1 pathway in macrophages: implications for therapies targeted to HDL. Circ Res 116:1101–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez BY, McDuffie K, Franke AA, Killeen J, Goodman MT (2004) Reports: plasma and dietary phytoestrogens and risk of premalignant lesions of the cervix. Nutr Cancer 49:109–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Song Y, Franke AA, Hu FB, van Dam RM, Sun Q (2015) A Prospective Investigation of the Association Between Urinary Excretion of Dietary Lignan Metabolites and Weight Change in US Women. Am J Epidemiol 182:503–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiterovich PO Jr. (2000) The metabolic pathways of high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides: a current review. Am J Cardiol 86:5L–10L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LA, Kennedy BE, Karten B (2016) Mitochondrial cholesterol: mechanisms of import and effects on mitochondrial function. J Bioenerg Biomembr 48:137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield FR, Tabas I (2005) Role of cholesterol and lipid organization in disease. Nature 438:612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales P, Hurst DP, Reggio PH (2017) Molecular Targets of the Phytocannabinoids: A Complex Picture. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod 103:103–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kennedy MA, Baldan A, Bojanic DD, Lyons K, Edwards PA (2004) Expression and regulation of multiple murine ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 mRNAs/isoforms that stimulate cellular cholesterol efflux to high density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem 279:45980–45989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngamukote S, Makynen K, Thilawech T, Adisakwattana S (2011) Cholesterol-lowering activity of the major polyphenols in grape seed. Molecules 16:5054–5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panee J, Gerschenson M, Chang L (2018) Associations Between Microbiota, Mitochondrial Function, and Cognition in Chronic Marijuana Users. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 13:113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner EA, Buettner H, Mittleman MA (2013) The impact of marijuana use on glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance among US adults. Am J Med 126:583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine C, Vincent M, Rogers A, Donat M, Ojike NI, Necola O, Yousef E, Masters-Israilov A, Jean-Louis G, McFarlane SI (2015) Metabolic Effects of Marijuana Use among Blacks. J Dis Glob Health 4:9–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas V, Garcia-Ruiz C, Fernandez-Checa JC (2016) Mitochondria, cholesterol and cancer cell metabolism. Clin Transl Med 5:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridlon JM, Alves JM, Hylemon PB, Bajaj JS (2013) Cirrhosis, bile acids and gut microbiota: unraveling a complex relationship. Gut Microbes 4:382–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodondi N, Pletcher MJ, Liu K, Hulley SB, Sidney S (2006) Marijuana use, diet, body mass index, and cardiovascular risk factors (from the CARDIA study). Am J Cardiol 98:478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenson RS, Brewer HB Jr., Chapman MJ, Fazio S, Hussain MM, Kontush A, Krauss RM, Otvos JD, Remaley AT, Schaefer EJ (2011) HDL measures, particle heterogeneity, proposed nomenclature, and relation to atherosclerotic cardiovascular events. Clin Chem 57:392–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen JT, Salonen R, Seppanen K, Rauramaa R, Tuomilehto J (1991) HDL, HDL2, and HDL3 subfractions, and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. A prospective population study in eastern Finnish men. Circulation 84:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevov M, Elfineh L, Cavelier LB (2006) Resveratrol regulates the expression of LXR-alpha in human macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 348:1047–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim-Selley LJ (2003) Regulation of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the central nervous system by chronic cannabinoids. Crit Rev Neurobiol 15:91–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit E, Crespo CJ (2001) Dietary intake and nutritional status of US adult marijuana users: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public health nutrition 4:781–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugamura K, Sugiyama S, Fujiwara Y, Matsubara J, Akiyama E, Maeda H, Ohba K, Matsuzawa Y, Konishi M, Nozaki T, Horibata Y, Kaikita K, Sumida H, Takeya M, Ogawa H (2010) Cannabinoid 1 receptor blockade reduces atherosclerosis with enhances reverse cholesterol transport. J Atheroscler Thromb 17:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Wedick NM, Pan A, Townsend MK, Cassidy A, Franke AA, Rimm EB, Hu FB, van Dam RM (2014) Gut microbiota metabolites of dietary lignans and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective investigation in two cohorts of U.S. women. Diabetes Care 37:1287–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto JK, Miller TL, Wang J, Jacobson DL, Geffner ME, Van Dyke RB, Gerschenson M (2017) Insulin resistance in HIV-infected youth is associated with decreased mitochondrial respiration. AIDS 31:15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uto-Kondo H, Ayaori M, Ogura M, Nakaya K, Ito M, Suzuki A, Takiguchi S, Yakushiji E, Terao Y, Ozasa H, Hisada T, Sasaki M, Ohsuzu F, Ikewaki K (2010) Coffee consumption enhances high-density lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux in macrophages. Circ Res 106:779–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan AM, Oram JF (2005) ABCG1 redistributes cell cholesterol to domains removable by high density lipoprotein but not by lipid-depleted apolipoproteins. J Biol Chem 280:30150–30157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidot DC, Prado G, Hlaing WM, Florez HJ, Arheart KL, Messiah SE (2016) Metabolic Syndrome Among Marijuana Users in the United States: An Analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Am J Med 129:173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Lan D, Chen W, Matsuura F, Tall AR (2004) ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:9774–9779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M, Hou M, Zhu H, Ma J, Tang Z, Wang Q, Li Y, Chi D, Yu X, Zhao T, Han P, Xia X, Ling W (2005) Anthocyanins induce cholesterol efflux from mouse peritoneal macrophages: the role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {gamma}-liver X receptor {alpha}-ABCA1 pathway. J Biol Chem 280:36792–36801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannis VI, Chroni A, Krieger M (2006) Role of apoA-I, ABCA1, LCAT, and SR-BI in the biogenesis of HDL. J Mol Med (Berl) 84:276–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.