Highlights

-

•

Upper gastrointestinal tract manifestations of Crohn’s disease are unusual.

-

•

There is limited literature guiding management decisions in affected patients.

-

•

This case report highlights surgical management in this aspect of Crohn’s disease.

Keywords: Case report, Crohn’s disease, Upper gastrointestinal obstruction, IBD surgery

Abstract

Background

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease that typically affects the distal part of the gastrointestinal tract (GI) such as the terminal ileum and colon. However, it can affect the upper GI tract, potentially resulting in complications such as strictures, but discussion of the management of such effects is limited in the surgical literature.

Case presentation

A 39 year old male was referred to our department with stricturing upper GI disease 20 years after CD diagnosis. He had a history of intermittent abdominal pain, nausea, frequent vomiting and weight loss. Imaging demonstrated a long stricture in the duodenum with proximal dilatation. There was no evidence of acute inflammatory Crohn’s disease. A Roux-en-Y bypass was performed to successfully relieve the obstructive symptoms.

Discussion

Proximal obstructive gastrointestinal manifestations of CD are a rare entity and require a full diagnostic workup and treatment in a specialist centre. A variety of systemic treatments, endoscopic procedures and surgical techniques are addressed in this paper.

Conclusion

Evidence for the optimal treatment of obstructive upper gastrointestinal CD is limited, but careful consideration of the extent of the disease, thorough preoperative planning and weighing up the benefits and risks can lead to a positive outcome for these patients.

1. Introduction

Despite the common adage that CD can affect anywhere along the GI tract from mouth to anus, pathology is mostly found in the colon or terminal ileum [1]. The prevalence of upper GI involvement (denoted L4 in the Montreal classification) in CD patients is thought to be between 0.5% and 5% if defined as pathology proximal to the terminal ileum, although this may be an underestimate due to upper GI endoscopy not being routinely carried out [2,3]. The rarity of upper GI involvement in CD has resulted in a relative paucity in the literature concerning its pharmacological management [3], whilst there is debate over which surgical options provide the most benefit. Here we present a case report describing a patient with upper GI symptoms of CD that required surgical management, and the report is structured using the Surgical Case Report (SCARE) 2020 Guidelines [4].

2. Case report

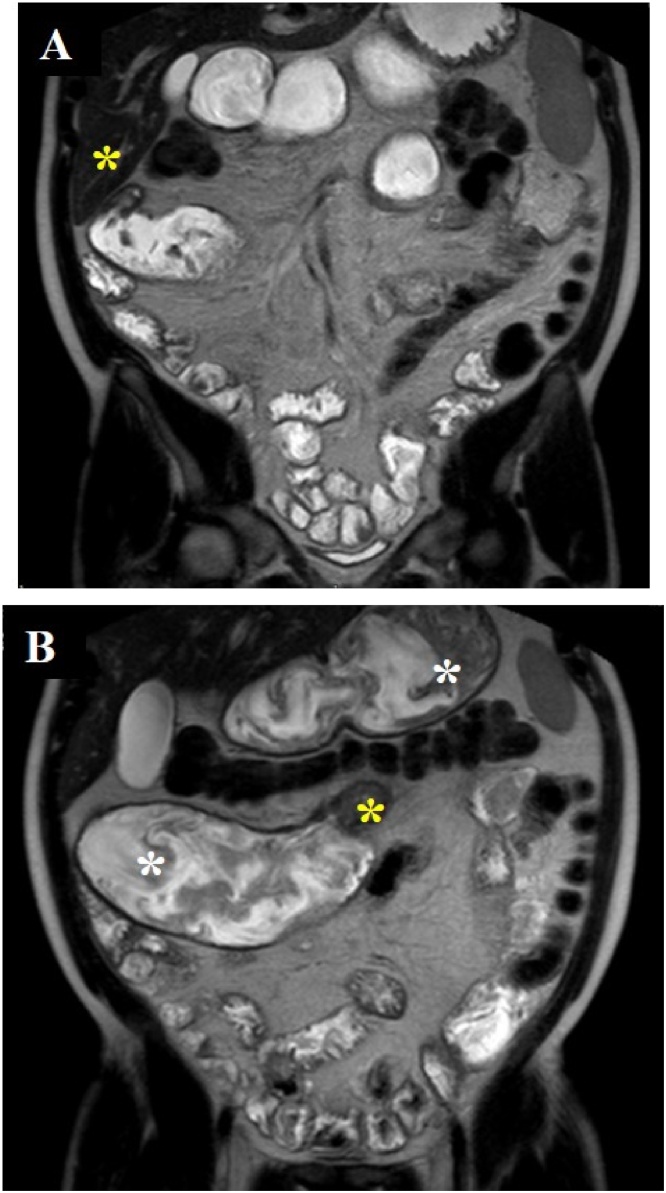

A 39 year-old male with an approximately 20-year history of CD began experiencing worsening abdominal aches and pain in addition to vomiting and weight loss towards the end of 2018, and he had resorted to a liquid diet. Throughout its clinical course his illness has affected the proximal small bowel, including duodenal haemorrhage three years prior to this latest presentation, and there was no previous history of bowel resection. This haemorrhage led to management with biologics, starting with infliximab, which was switched to adalimumab and finally vedolizumab. Symptomatic stricturing disease developed after the switch to vedolizumab: an MRI scan revealed stricturing in D3 of the duodenum and in the proximal jejunum, in addition to dilatations upstream of the lesions (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

Coronal MRI T2 images with Buscopan prior to surgery. A: Stricturing in D3 of the duodenum (yellow asterisk).

B: Stricturing in the proximal jejunum (yellow asterisk) in addition to dilatation of the stomach, D4 of the duodenum and jejunum proximal to the jejunal stricture (white asterisks).

After referral to an IBD MDT, the patient underwent a laparotomy and Roux-en Y bypass procedure in early 2019. A jejunal segment resection of the strictured segment was performed, and then a transmesocolic side-to-side gastrojejunal anastomosis was formed. To restore the biliopancreatic continuity, a jejunal-jejunal end-to-side anastomosis was formed, 40 cm downstream of the gastrojejunostomy. Pathologic analysis of the jejunal resection specimen revealed granulomas indicating CD of mild to moderate activity and there was no evidence of malignancy. The patient recovered from the surgery and after several days, having received total parenteral nutrition and then recommencing oral intake, was discharged from hospital.

3. Discussion

3.1. Diagnosis of upper GI involvement in Crohn’s disease

Ileocolonoscopy is the first-line investigation for diagnosing CD, but the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) consensus suggests that the small bowel should also be investigated to determine the extent of upper GI pathology [5]. However, upper GI endoscopy is not routinely performed in adults with suspected CD, and the above ECCO recommendation is based on expert opinion only [6].

A study on the prevalence of upper GI involvement in newly diagnosed adult patients with CD using upper GI endoscopy in addition to ileocolonoscopy found 41% had upper GI involvement, but only 32% of patients had upper GI symptoms, indicating that macroscopic lesions in the upper GI tract are often missed. However, the authors question the utility of an additional investigation if the lesions identified do not cause any symptoms. [7]

Alternatively, imaging modalities such as CT and MRI are useful tools for identifying upper GI complications such as stricturing disease [5] and are less invasive than endoscopy. Furthermore, Greuter et al. [6] suggest that there is no significant difference in complication-free survival when comparing patients with CD and upper GI involvement to CD patients without upper GI involvement at the time of diagnosis [6].

3.2. Pharmacological management of upper GI Crohn’s disease

Unfortunately there is a lack of evidence in the literature about medical management relating to upper GI CD, and therefore this is generally based on concurrent distal disease activity [3]. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can be indicated in CD if there is mild disease in the oesophagus, stomach or duodenum [5]. PPIs may help relieve upper GI symptoms but they do not address the inflammatory component driving CD itself [3]. Some studies have drawn links between the potential role of microbiota in IBD and the fact that PPIs can affect them. Shah et al. [8] found that PPI usage by IBD patients, including CD patients, was associated with an increased risk of hospitalisation and surgical intervention related to IBD [8], so there might be adverse interactions between this drug and CD pathophysiology. Possible mechanisms by which PPIs might exacerbate IBD include the loss of the gastric antimicrobial barrier and modulation of the immune system [9]. Meanwhile, there is some discussion of the use of biologics in upper GI CD, with one report suggesting that the anti-TNF agent infliximab reduced a duodenal stricture and inflammation in a case of duodenal CD [10].

3.3. Surgical and endoscopic management of stricturing in upper GI Crohn’s disease

Stricturing disease is an important complication in upper GI CD, and resulting obstructions should ideally be attenuated while bowel length is conserved [11], preventing issues such as short bowel syndrome. ECCO and the European Society of Colo-Proctology (ESCP) have set out guidelines for the surgical management of CD, and the procedures suggested for pathology between the stomach and the jejunum include distal gastrectomy, Roux-en Y gastrojejunostomy (i.e. a bypass) and strictureplasty [12]. Additionally, non-surgical endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD) can be used in the management of stricturing disease.

EBD involves the endoscopic placement of a balloon at the location of a stricture followed by inflation to reduce the size of the stricture. As a treatment for upper GI CD it is safe and minimally invasive, but the need for surgery following EBD is common due to a high recurrence rate of obstructive symptoms [1], with between 30% and 50% of EBD-treated patients needing surgery, depending on study criteria [13]. Furthermore, a retrospective cohort study, albeit with small numbers, showed that significantly fewer re-interventions are required following surgical resection in CD compared to EBD [14].

Alternatively, strictureplasty can be carried out, and this is suggested when possible for more distal duodenal strictures e.g. at the level of D3 to avoid issues such as dumping syndrome [12]. For example, the Heineke-Mikulicz technique involves making a longitudinal incision at the site of a stricture and then suturing transversely, enabling bypass of the scar tissue without bowel resection. There is some evidence to support strictureplasty in the treatment of jejunal strictures, as a systematic review and meta-analysis showed a recurrence rate of only 23% following strictureplasty [15].

Finally, bypass surgery, such as a Roux-en Y gastrojejunostomy, may be used in the surgical management of upper GI strictures in CD. The literature lacks recent studies where different surgical techniques have been directly compared, which is perhaps unsurprising as upper GI manifestations of CD are unusual [16]. Two studies with similar numbers of patients came to opposite conclusions about whether strictureplasty should be favoured over bypass surgery for duodenal CD or vice versa [17,18] so it is impossible to be sure which has the best outcomes. Despite the risk of significant complications such as anastomotic leakage, Roux-en Y bypass is arguably the most appropriate surgery in the case above as duodenal and jejunal stricturing were present. The lower risk of recurrence is also an argument to be taken into account.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the diagnosis and management of upper GI involvement in CD is fraught with difficulty, and the lack of literature on this topic means that patient care relies on subjective decisions. Predicting and diagnosing upper GI involvement is arguably more difficult in adults than identifying ileocolonic disease. To add further complexity, upper GI endoscopy may find lesions that do not cause symptoms and don’t need medical management and intervention. Furthermore, there is little evidence supporting any type of tailored pharmacological management strategy for CD with upper GI features. Finally, there are multiple surgical options that can be used to treat upper GI complications of CD, but the case in this report highlights the difficulty in choosing one procedure over the others since there is little evidence for guidance. Further studies regarding this small patient group are therefore needed to improve the outcomes of care.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

None to declare.

Ethical approval

NA.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Orrell M – Data collection, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

van 't Hullenaar C – Data collection, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

Gosling J – Writing – Review & Editing.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Michael Orrell.

Cas van 't Hullenaar.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Torres J., Mehandru S., Colombel J.-F., Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1741–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annunziata M.L., Caviglia R., Papparella L.G., Cicala M. Upper gastrointestinal involvement of Crohn’s disease: a prospective study on the role of upper endoscopy in the diagnostic work-up. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012;57:1618–1623. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pimentel A.M., Rocha R., Santana G.O. Crohn’s disease of esophagus, stomach and duodenum. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019;10:35–49. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v10.i2.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomollón F. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J. Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(1):3–25. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greuter T. Upper gastrointestinal tract involvement in Crohn’s disease: frequency, risk factors, and disease course. J. Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(12):1399–1409. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horjus Talabur Horje C.S. Prevalence of upper gastrointestinal lesions at primary diagnosis in adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016;22(8):1896–1901. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah R., Richardson P., Yu H., Kramer J., Hou J.K. Gastric acid suppression is associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 2017;95(3):188–193. doi: 10.1159/000455008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juillerat P. Drugs that inhibit gastric acid secretion may alter the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;36(3):239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odashima M. Successful treatment of refractory duodenal Crohn’s disease with Infliximab. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007;52(1):31–32. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Racz J.M., Davies W. Severe stricturing Crohn’s disease of the duodenum: a case report and review of surgical options. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2012;3(7):242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bemelman W.A. ECCO-ESCP consensus on surgery for Crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(1):1–16. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klag T., Wehkamp J., Goetz M. Endoscopic balloon dilation for Crohn’s disease-associated strictures. Clin. Endosc. 2017;50(5):429–436. doi: 10.5946/ce.2017.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greener T. Clinical outcomes of surgery versus endoscopic balloon dilation for stricturing Crohn’s disease. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2015;58(12):1151–1157. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto T., Fazio V.W., Tekkis P.P. Safety and efficacy of strictureplasty for Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2007;50(11):1968–1986. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lightner A.L. Duodenal Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018;24(3):546–551. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T. Outcome of strictureplasty for duodenal Crohn’s disease. Br. J. Surg. 1999;86:259–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Worsey M.J., Hull T., Ryland L., Fazio V. Strictureplasty is an effective option in the operative management of duodenal Crohn’s disease. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1999;42:596–600. doi: 10.1007/BF02234132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]